« Prev Next »

Medical and psychological studies involving human subjects remain a critical factor in advancing our scientific knowledge. Despite historical episodes of tragically unethical treatment of humans in the name of medical science, such as the Tuskegee study, the need for human subjects in biomedical research is vital for the development of any new drug. But how can we balance the welfare of human research subjects with the need for valuable data from human experimentation? Several solutions to this conundrum have been proposed, but none is without its flaws.

Learning from the Tuskegee Study

Sadly, there is a long history of the unethical treatment of human subjects in various types of medical and biological research. For example, one of the most notorious clinical studies of all time was initiated in 1932, with the goal of tracking the progression of untreated syphilis infection. At the time, treatments for syphilis included highly toxic mercury, bismuth, and arsenic-containing compounds of questionable effectiveness. The study was a collaboration between the Tuskegee Institute and the U.S. Public Health Service in Alabama, and was intended to determine the progression of the disease, the effectiveness of treatments at different stages, and modes of disease transmission. Doctors recruited 399 black men thought to have syphilis, as well as 201 healthy black men as controls. Study participants were kept unaware of their diagnosis of syphilis but, in return for participating in the study, the men were promised free medical treatment if they tested positive, rides to the clinic, meals, and burial insurance in case of death.

The initial aim of the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, as it was known, was perfectly legitimate: to gather medical knowledge. However, during the mid-1940s, when penicillin had been shown to be a highly safe and effective cure for syphilis infection, the researchers did not abandon the study, but continued to subject their unwitting participants to painful complications and death due to syphilis infection until 1972, when a story about the study appeared in the national press. Public outcry caused an abrupt end to this research, followed by the filing of a class action lawsuit against the U.S. government on behalf of the survivors.

Structuring a Clinical Drug Trial

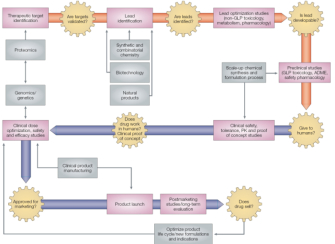

Of course, a great deal of research and testing occur before drugs are subject to clinical trial. First, after basic research and screening, promising substances are moved into the development stage. While in development, the drugs are tested in vitro. The next step involves preclinical trials, in which a drug's effectiveness and toxicology are established in animal models, like mice. Following successful animal studies, the substance is moved through three phases of clinical testing that involve human subjects. The first phase establishes the metabolism and the side effects of the drug treatment; the second phase gauges the efficacy of the treatment; and the final stage evaluates the overall risk-benefit ratio.

The entire process of drug discovery must meet federally mandated standards of scientific practice, and all drugs that yield successful trial results must receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) before being released in the market. Moreover, human and animal testing are also subject to scrutiny by, respectively, institutional review boards (IRBs) and institutional animal care and use committees (IACUCs), both before and during drug trials. Finally, long-term efficacy trials after a drug becomes available help document any additional effects and are an integral part of producing a safe product (Figure 1).

Making Experimentation Safer: The Creation of IRBs

When the tragic ethical misconduct of the Tuskegee study came to light in the 1970s, it highlighted the importance of clearly defined regulations on human testing. Thus, on July 12, 1974, the National Research Act was signed into law, thereby creating the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report of 1979 is a summary of the Commission's recommendations. This report is a statement of basic principles and guidelines to assist in resolving the ethical problems that surround the conduct of research with human subjects. One of the major outcomes of this document was the mandate of institutional review boards (IRBs) for any federally funded research program involving human subjects.

As previously mentioned, the purpose of an IRB is to assure, both in advance and by periodic review, that appropriate steps are taken to protect the rights and welfare of humans participating as subjects in a research study. Every institution intending to carry out research involving human subjects must establish a committee of at least five members with expertise in science, ethics, and other nonscientific areas to serve as an IRB. IRBs evaluate proposed research protocols to verify that they are scientifically sound and meet all legal and ethical standards. These boards can approve, disapprove, or modify any research protocol and must conduct reviews of approved research protocols at least yearly (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2004). All IRBs must be registered with the Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

Informed Consent

A key requirement for IRB approval of human research is to obtain informed consent from all study participants. Informed consent is not just a form; it is a process. Information must be presented to the participation candidates to aid their voluntary decision of whether or not to take part in the research (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services). At a minimum, consent documents should include the following:

- A description of the expected overall experience

- The extent to which a participant's personal information will be kept in confidence

- Benefits to the subject that may be reasonably anticipated

- The potential for injury and the nature of compensation or treatment that will be provided in case an injury is sustained

- Whom to contact with questions about the research, one's rights as a research subject, and research-related injuries

- A clear statement of the voluntary nature of subject participation and the subject's right to withdraw from the study at any time for any reason

Providing such thorough background and guidelines to study participants ensures mutual collaboration and minimizes the risks associated with uninformed consent.

Recruitment of Volunteers for Human Studies

HHS expects IRBs to review any advertisements for the active recruitment of volunteers to assure that these advertisements are not unduly coercive and do not promise a cure. This is especially critical when a study may involve subjects who are likely to be vulnerable to undue influence, such as people who are desperately ill (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 1998). The FDA recommends that advertisements to recruit subjects provide the information that prospective subjects need to determine their eligibility and interest, while refraining from active encouragement. A decision to take part in a drug study is often driven by the need for more effective treatment, and it should thus be accompanied by detailed and unbiased information.

Access to Testing or Treatment That Is Otherwise Unavailable

Gaining access to a potentially lifesaving treatment is sometimes the impetus for individuals to enter into a clinical trial. However, the strongest support of the effectiveness of a drug comes from randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studies. In this type of study, patients are randomly assigned to receive either the test drug or a placebo. Neither the patients nor the researchers know which participants have been assigned to which group (hence the term "double blind"). This type of study eliminates evaluator bias when assessing the outcome of the drug treatment. In this type of clinical trial, volunteers have only a 50% chance of receiving the drug being tested, a fact that would be disclosed on the consent forms.

The FDA recognizes that there are individuals with serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions who lack any alternative treatments. In an effort to help such individuals while still maintaining the integrity of the scientific process that brings new drugs to the market, the FDA has made significant regulatory changes to its policy in recent years to make investigational therapies more widely available (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2008). Proposed in 2006, these changes attempt to increase awareness in the health care setting of the availability of investigational drugs, and to encourage drug companies to make the products available to patients by allowing recompense for the provision of the drugs to such programs. Financial Incentives for Risky Drug Trials

Financial incentives are often used when health benefits to research subjects are remote or nonexistent. For instance, in a 2004 study conducted at the University of California at San Diego (UCSD), 127 volunteers ages 18 to 35 were paid 15 dollars an hour to be exposed to incremental doses of chloropicrin, a fumigant used in a variety of pesticides and tear gas (Lee & Clark, 2005). The experiments intended to establish at what level of chloropicrin the participants would notice the exposure to the chemical, as well as to establish any associated health risks that were not observed in animal testing. The results of this study were used to provide data for establishing accurate guidelines regarding the distances that should be maintained between homes and businesses and sites of chloropicrin fumigation. The data were also used to assess the welfare of field-workers who could regularly come in contact with chloropicrin or of passersby who might be accidentally exposed to the chemical. Although the study was heavily criticized by two California lawmakers who issued a report alleging that such testing unnecessarily puts participants at risk and targets college students in need of money, the study officials insisted that the research met all legal and ethical standards and that all participants were fully informed.

Disclosure of Subjects’ Medical Information

Some studies collect information that, if disclosed, could have adverse consequences for study subjects, such as damage to their financial standing, employability, insurability, or reputation. For such studies, certificates of confidentiality can be requested and issued by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and other HHS agencies to protect identifiable research information from forced or compelled disclosure. These certificates allow the investigator and others who have access to research records to refuse to disclose identifying information on research participants in civil, criminal, administrative, legislative, or other proceedings, whether federal, state, or local. A certificate may be an important deciding factor for some individuals who are considering whether to participate in a study.

An alternative to this scenario is one in which full disclosure of all test information is permitted by the study subject. An example of this is the Personal Genome Project (Harvard University), an open-ended research study that aims to improve our understanding of genetic and environmental contributions to human traits. To that end, this study recruits volunteers who agree to the collection of full genomic sequence data and other personal information to be shared with the scientific community and the general public. One goal of the project is to improve the understanding of personal genomics and its potential use in the management of human health and disease. Changing with the Times

The establishment of appropriate ethical protections for human research participants has not been static; it has evolved over time, alongside the evolution of biomedical research and social values. For example, judges presiding over the Nuremberg trials of the Nazi doctors who performed experiments on concentration camp prisoners recognized a need for oversight of medical experiments involving humans. Thus, the Nuremberg Code was formulated in 1947, and it provided guidelines for research that are still adhered to today. Similarly, outrage over the Tuskegee syphilis study led to the Belmont Report, which ultimately resulted in official regulation of human subject research by the United States government and the IRB requirement. These and other events have resulted in major changes in the way human studies have subsequently been conducted.

More recently, the question of financial interests influencing risky research protocols has come to the forefront with the death of 18-year-old gene therapy study volunteer Jesse Gelsinger in 1999 (News Weekly, 2000). Gelsinger was involved in a trial that aimed to demonstrate the use of a viral vector in replacing a defective ornithine transcarbamylase gene. Unfortunately, he died of major organ failure due to a massive immune response to the viral vector. Amid accusations of undisclosed risks and possible side effects that might have stopped the study before Gelsinger's death, the FDA temporarily halted all such studies while the NIH conducted thorough reviews of all adverse reactions and deaths associated with gene therapy trials.

Future scientific experiments will test medical treatments that are outside the scope of modern testing standards; therefore, these experiments will undoubtedly prompt further modifications to the current regulations that ensure the well-being of human research subjects. Throughout this process of evolution, however, the protocol for using human subjects in medical trials will most certainly continue to be tightly regulated.

References and Recommended Reading

Harvard University. Personal Genome Project. (accessed on September 29, 2008)

Lee, M., & Clark, C. California Lawmakers want to stop human pesticide testing. SignOnSanDiego.com (2005) (accessed on September 29, 2008)

National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Belmont Report: Ethical principles and guidelines for the protection of human subjects of research. (National Institutes of Health Office of Human Subjects Research, 1979) (accessed on September 29, 2008)

News Weekly. Bioethics: Gene therapy business: The tragic case of Jesse Gelsinger. (2000) (accessed on September 29, 2008)

Office of Human Subjects Research. Directives for human experimentation: Nuremberg Code. Reprinted from Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law 10(2), 181–182. (U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1949) (accessed on September 29, 2008)

Pritchard, J. F., et al. Making better drugs: Decision gates in non-clinical drug development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2, 542–553 (2003) (link to article)

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. Office for Human Research Protections. (accessed on September 29, 2008)

———. Guidelines for the conduct of research involving human subjects at the National Institutes of Health. (2004) (accessed on September 29, 2008)

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Recruiting study subjects. (1998) (accessed on September 29, 2008)

———. Speeding access to important therapeutic agents. (2008) [PDF]

Figure 1: Key decision gates in drug development.

Figure 1: Key decision gates in drug development.