« Prev Next »

In a way, personalized medicine has been around for as long as people have been practicing medicine. In fact, Hippocrates, Greek physician and so-called "Father of Western Medicine" who practiced some 2,500 years ago, was himself a proponent of personalized medicine (Sykiotis et al., 2005). For example, in one of his over 70 works of ideas and teachings, Hippocrates wrote about the individuality of disease and the necessity of giving "different [drugs] to different patients, for the sweet ones do not benefit everyone, nor do the astringent ones, nor are all the patients able to drink the same things."

Whereas Hippocrates evaluated factors like a person's "constitution," age, and "physique," as well as the time of year, to aid his decision making when prescribing drugs, twenty-first-century personalized medicine is all about DNA. Today, the goal of personalized medicine is to utilize information about a person's genes, including his or her nucleotide sequence, to make drugs better and safer. But even though scientific and industry experts have been predicting the arrival of DNA-based personalized medicine since at least the 1980s and the early days of the Human Genome Project, there are only a handful of gene-based personalized medicine success stories to date.

Her2/neu and Response to Breast Cancer Treatment

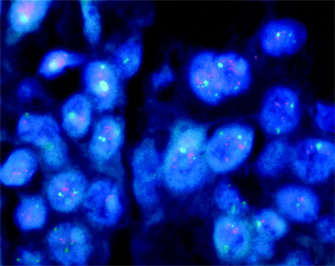

Tumors with overexpressed Her2/neu are said to be Her2-positive (Figure 1). Physicians prescribe Herceptin only to women with these types of tumors. Herceptin acts by binding to the Her2 receptors and interfering with their out-of-control cell signaling; studies have shown that the drug is a much more effective treatment in women with Her2-positive tumors than in women with Her2-negative tumors. Moreover, not only does Herceptin not work as well against cancer cells with normal levels of Her2 expression, but it can sometimes do more harm than good. That is because in all patients, no matter what their Her2/neu status, Herceptin increases the risk of heart dysfunction. In fact, the risk is worrisome enough that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the regulatory agency ultimately responsible for deciding which drugs can be prescribed and under what circumstances, has stated that physicians should prescribe Herceptin only to those women who would likely truly benefit—in other words, only those women who test positive for Her2/neu. Otherwise, the risk of heart failure is just too great to justify use of this drug. Thus, women with advanced breast cancer are routinely tested for Her2/neu overexpression before any decisions are made about whether to prescribe Herceptin versus some other drug, because as good as Herceptin might be, to use Hippocrates' words, "the sweet ones do not benefit everyone."

There remain some problems, however, with Herceptin and Her2/neu testing, not the least of which is the fact that while the drug works better in Her2-positive patients than it does in Her2-negative patients, only about half of all Her2-positive patients actually benefit from it. Some scientists say a better test is needed; however, the present test represents the best technology science currently has to offer. At least the test is actually being used and has some benefit, unlike CYP450 gene testing (Katsanis et al., 2008).

CYP450 and Response to Antidepressants

The CYP450 genes code for a large family of proteins known as the cytochrome P450 enzymes. Certain polymorphisms among the CYP450 genes have been associated with the function and strength of a class of drugs known as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). SSRIs are a commonly prescribed class of antidepressants. Some people metabolize SSRIs quickly, others slowly, depending on their genetic makeup. Individuals who metabolize these drugs quickly typically require higher doses because the drug is broken down so quickly, whereas slower metabolizers cannot tolerate large doses. In theory, because of this association between CYP450 variation and SSRI function, it should be possible to assay people's CYP450 genetic makeup and predict not necessarily whether they would benefit from SSRIs (as is the case with Her2/neu testing and Herceptin), but rather which SSRI to use and what dose would be most beneficial.

Unfortunately, these results have not been corroborated in clinical studies. For example, in 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the largest public health agency in the United States, formed what they called the Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. The group was charged with investigating and evaluating the current state of genetic testing. In December 2007, the group issued recommendations about CYP450 testing in particular, concluding "there is no evidence linking testing for CYP450 to clinical outcomes in adults treated with SSRIs." In other words, testing for CYP450 polymorphisms doesn't matter. So, even when physicians test their patients for CYP450 and make treatment decisions based on the known association between CYP450 variation and SSRI metabolism, their patients respond to therapy no differently than patients who are not tested.

The challenges in translating the preliminary CYP450 association results into clinically relevant information is a good example of what many experts in the field consider to be one of the greatest problems with DNA-based personalized medicine: It is extremely difficult to turn all this wonderful science about gene-drug associations into clinical reality. Furthermore, according to a Science magazine article authored by scientists from Johns Hopkins University's Genetic and Public Policy Center, this problem is compounded by the fact that, despite the huge gap between theory and clinical reality, a growing number of businesses offer CYP450-testing services. While some of these companies simply test for the presence of one or another CYP450 variant, at least four of them also make claims about what the information means for prescribing and dosing SSRIs. The authors of the Science article surveyed the websites of the four companies and found that the information was inconsistent, which they interpreted as a reflection of the lack of consensus in the scientific community regarding what the various CYP450 polymorphisms really reveal about which SSRIs to prescribe to which patients and at what doses (Katsanis et al., 2008). With the lack of conclusive evidence regarding the CYP450-SSRI association, it is highly concerning that direct-to-consumer diagnostic testing companies offer services that supposedly help individuals make this and other treatment decisions.

References and Recommended Reading

Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: Testing for cytochrome P450 polymorphisms in adults with nonpsychotic depression treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Genetics in Medicine 9, 819–825 (2007)

Katsanis, S. H., et al. A case study of personalized medicine. Science 320, 53–54 (2008) doi:10.1126/science.1156604

Sykiotis, G. P., et al. Pharmacogenetic principles in the Hippocratic writings. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 45, 1218–1220 (2005)