Abstract

In the digital age, as social media evolves into a new and significant centre for the dissemination of Chinese folk beliefs, the Malaysian Chinese have actively shared information about these folk beliefs on their social media platforms. The dissemination has transcended regional barriers, encouraging more Malaysian Chinese across various states to actively participate in public discussions on this topic. This study delves into Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs by analysing data from Facebook. A comprehensive examination of 4012 text posts was conducted using the latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) model for topic modelling. The analysis identified four main themes on social media: ‘Practitioners Worship’, ‘Temple Activities’, ‘Deity Legends’, and ‘Merchandise about Deity Statues’. Based on integrating social construction theory and media ecology theory, the study first explores the varied constructors, including practitioners, temple organisations, media organisations, and merchants. Secondly, Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media present characteristics of utilitarianism, regional diversity, multiple social functions, flowing realms, strong Taoist elements, commercialisation, and a close relationship with the Spring Festival. Furthermore, ‘Safety and Peace’, ‘Pray for Demands’, and ‘Merits and Virtues’ form an interconnected semantic nexus. Hence, the findings theoretically highlight the interaction and significance of social media in the construction and practice of folk beliefs within the Malaysian Chinese community. Practically, this research provides valuable insights into the understanding and dissemination of Malaysian Chinese religious culture in the digital era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The earliest written record of the Chinese worshipping and offering sacrifices to deities in the Malay Peninsula can be found in the Shilin Guangji during the Southern Song dynasty (Chen, 1999). During the Ming and Qing dynasties, a large number of Chinese people from the Fujian and Guangdong provinces migrated to the Malay Peninsula. The deities predominantly revered in these two provinces were also introduced to Malaya, acknowledged as ‘incense-pot branches’ originating from China (Tan, 2014). Chinese secret societies presented themselves through various means, and the establishment of Chinese temples was one of these distinctive manifestations (Mak, 2017). During the early formation of Chinese diaspora communities, Chinese temples became the information centre of the community due to their religious cohesion. With the advancement of print media in the late 19th century, newspapers started to greatly influence the dissemination of Chinese folk beliefs. In 1881, the first Chinese-language daily newspaper in the Straits Settlements, Le Bao was founded. Subsequently, Chinese newspapers started featuring reports on Chinese folk beliefs. For example, the Le Bao (Su and Chen, 2010) published a story about the procession on deities: “The Chinese in all districts of Johor annually organised a procession on deities every 20th day of the first lunar month. The procession lasted for one day, with a two-night parade in the evening featuring drama troupes.” With the advancement of technology, the modes of spreading Chinese folk beliefs have also transformed, particularly through the popularity of social media platforms like Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, and Twitter. Among these platforms, Facebook has become one of the most widely used websites globally since its launch in February 2004 (Anderson et al., 2012). Notably, it stands out with the highest usage rate in Malaysia (Datareportal, 2023). Facebook provides a wealth of textual information on Chinese folk beliefs, which has helped break down regional boundaries and encourage more Malaysian Chinese from different regions to participate in advocacy on this topic.

There is a significant body of research on the folk beliefs of the Malaysian Chinese community, and the research methods employed by scholars have evolved over time. From the 1930s to the 1950s, scholars like Han Wai Toon (1939), Hsu Yun Tsiao (1951), and Tan Yeok Seong (1952) utilised historical documentation method to investigate the attributes and origins of deities such as Da Bo Gong and Ma Zu in publications like Journal of the South Seas Society and Sin Chew Daily, creating a diverse research landscape. In the 1960s and 1970s, local scholars began to emphasise the use of field research methods for studying Chinese folk beliefs in Malaysia. For example, Choo (1968) conducted research using the fieldwork method to collect data on the evolution, distribution, categories, and operational models of Chinese temples in Kuala Lumpur. This research pioneered a trend where local scholars explored Malaysian Chinese religious practices via fieldwork (Soo, 2012). During the 1980s and 1990s, scholars expanded their studies by conducting individual case studies on Dejiao (Tan, 1985), Nine Emperor Gods belief (Cheu, 1982), and I-Kuan Tao (Soo, 1997) using the fieldwork method. They also conducted extensive collections of cultural relics and historical materials, such as inscriptions found in Chinese temples (Wolfgang and Chen, 1982). At the beginning of the 21st century, the academic community emphasised the study of the dissemination networks and immigrant interactions of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs by combining historical documents with field research methods (Chen, 2010; Cheng, 2006). With the rise of digital humanities, scholars have initiated interdisciplinary collaborations to delve into the digitised research of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. In 2017, Kenneth (2021) led a team that initiated an extensive project using geographic information systems (GIS) for comprehensive data collection and code organisation of Chinese clan associations, temples, and cemeteries in Singapore and Malaysia. This represents an interdisciplinary approach that combines historical documentation methods, field research methods, and geographic methods. Hue et al. (2023) used the same methodology to demonstrate the development of Chinese folk beliefs in Johor. Overall, in the field of research on Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs, there has been a shift from singular applications to interdisciplinary approaches. The focus of research subjects has shifted from micro-level historical verification to case studies, and subsequently, to macro-level discussions.

However, the topic of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media has yet to be studied. Several factors contribute to this. Firstly, social media content predominantly focuses on current affairs, entertainment, and trending topics, resulting in less attention being paid to Chinese folk beliefs. Secondly, the lack of systematic content collection specifically targeting Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media hinders scholarly exploration in this area. Additionally, there has been no utilisation of natural language processing (NLP) methods, such as the application of latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA), to study Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. Therefore, this study selects Facebook as the social media platform to collect data and analyse the topics of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs using topic modelling, a machine learning method that organises unstructured data according to latent themes (Zhao, and Chen et al., 2015). Through this approach, the research endeavours to explore the content topics of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on Facebook. By integrating social construction theory with media ecology theory, the study does more than pinpoint the diverse roles involved in content creation; it constructs a theoretical framework that treats social media, constructors, and content (text posts) as interactive elements. This framework is used to explore the characteristics and real-life implications of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs within social media platforms, thereby offering a nuanced and multidimensional comprehension of the religious culture in the Malaysian Chinese community.

Definition

As the Chinese became established on the Malay Peninsula, the systems of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs and Chinese indigenous folk beliefs became closely related. When it comes to the term of ‘Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs’, this study uses the definition of ‘Chinese folk beliefs’ to identify. This term has been explored by many scholars. According to Lu (2012), the term ‘Chinese folk belief’ has been widely used in academic research and daily life in mainland China but is less commonly used in other regions, where it is often referred to as ‘popular religion’ or ‘folk religion’. Yang (1961) referred to this as ‘diffused religion’. Li (1997) proposed that the subject of Chinese folk belief is the practitioners, and the object is gods, ancestors, and ghosts. The belief rituals include ancestor worship, seasonal offerings, deity worship, annual festivals, life ceremonies and symbols.

Theoretical framework

As communication technologies and media platforms undergo rapid evolution, social media emerges as a novel medium that enable individuals to connect, interact, produce, and share content (Lewis, 2010), thereby subverting the traditional one-to-many communication model dominant in earlier mass communication theories (Wohn and Bowe, 2014). This shift not only enhances both human-human and human–computer interactions (Carr and Hayes, 2015), but also enriches the diversity of the media ecosystem (Zhao et al., 2016). Social media platforms have become critical sites for understanding the construction of reality and the media ecology in contemporary society.

The application of social construction and media ecology theories offers new perspectives for this study, shaping the understanding and knowledge of the construction of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media in the digital era. Adoni and Mane have previously discussed the integration of social constructivism into media studies (1984). According to the theory of social construction, individuals are perceived as creators of a socially constructed reality within their social world, where reality is essentially formed and constructed by human activity (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). As constructors of real society, individuals engage in the process of social construction not only as recipients of information but also as creators of information and knowledge (Adoni and Mane, 1984). Similarly, in the virtual world of social media, constructors (users and content producers) participate in content creation based on their real-life experiences, backgrounds, and cultural understandings. This content represents the constructors’ interpretations and understandings of the real world (Gergen, 1985). Through their participation in all aspects of social media, they become the constructors of social media (Jenkins, 2006), playing various roles across different stages of the social media dissemination process: producers, disseminators, and responders. From another perspective, the theory of media ecology examines the interactions between media, technology, and human communication within specific cultural contexts (Gamaleri, 2019). McLuhan (1964) posits that media are not merely passive channels for information transmission but actively shape both the content and context of communication. Social media fosters a culture that enables constructors to engage and self-present selectively, whether in real-time or asynchronously (Carr and Hayes, 2015). This builds a two-way interactive communication channel that allows for interaction and feedback (Kent, 2010).

To sum up, a dynamic theoretical framework that integrates the principles of social constructionism and media ecology provides an effective lens for analysing text posts about Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on Facebook. This framework encapsulates three pivotal elements: constructors, social media, and content, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The interplay among these components can be elucidated as follows: in the context of the digital age, constructors employ social media to circulate content, which is concurrently influenced by and influential upon the technological affordances and cultural norms of the platform. In turn, the content impacts the perceptions and behaviours of the constructors (Papacharissi, 2022; Reese et al., 2001). The dynamic interaction among constructors, social media, and content engenders shared meanings and knowledge, modulated by media characteristics and further evolved within the sociocultural milieu. The iterative interaction among constructors, social media, and content elucidates how these elements converge to influence and be influenced by the virtual realm they represent. This dynamic interplay significantly contributes to broader discussions on how Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs are constructed and manifested on social media in the digital age.

Research method

Data collection

The term ‘Chinese folk belief’ is commonly used in academic circles but can be confusing to the general public (Lu, 2010). In Malaysian Chinese society, folk beliefs are often expressed through specific rituals, temples, and deities. This study explores Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs by examining the names of deities. To gather information, there were two researchers who conducted a search on https://www.angkongkeng.com, a website that provides details about nearly 2000 Chinese temples dedicated to deity worship in Malaysia. A total of 191 names of main patron saints as keywords before December 31, 2022, were collected. The corresponding Chinese characters for the names of 191 deities are listed in the Supplemental material (see Supplementary Table S1). From January 22, 2023, to February 14, 2023, two researchers searched information on Facebook using these keywords. This period coincided with the Spring Festival, an important time for the Malaysian Chinese community, characterised by grand celebrations and traditional customs. The Spring Festival holds great significance in the Chinese community as it represents a period of heightened interactions between humans and deities (Chen, 2022). During this time, Malaysian Chinese individuals tend to share text posts on social media, recounting their real-life interactions and experiences with deities. This study manually collected Chinese text posts published about these deities, and upon entering the name of a deity, numerous posts would appear on the Facebook webpage. Considering the balance of data collection in deities, only the first 25 text posts are collected without skipping or selecting. This process revealed two scenarios: some deities were highly active and had a substantial number of text posts, while others showed little to no activity on social media, resulting in limited or no available information about them. For the active deities, a standard of 25 text posts per deity was collected. However, for the inactive deities, only the data that was available at the time could be gathered. Consequently, a total of 4358 text posts were obtained from Facebook.

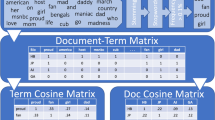

After collecting and cleaning the data, topic modelling was utilised to extract meaningful topics and discover latent relationships among the information. Topic modelling is a powerful technique in text mining and data mining, which helps in finding connections between data and text documents (Jelodar et al., 2019). There are several methods for topic modelling, and LDA has gained popularity in various research fields. LDA accurately mines the content topics by assuming the existence of potential topic vectors and modelling the document as a set of independent words while assigning a mixed topic vector to each document (Wang, 2017). In this study, the LDA method was employed, a technique that conceptualises each document as a composite of various topics, thereby allowing for a more nuanced analysis of the underlying thematic structures (Barde and Bainwad, 2017). Each topic is represented by a probabilistic distribution over words (Blei et al., 2003). To estimate the marginal distributions of variables of interest, Gibbs sampling, a simulation tool for obtaining samples from a non-normalised joint density function, is applied (Alan, 2000). This enables the exploration of topics within the data pool using the LDA model (Griffiths and Steyvers, 2004).

Processing

The framework of the study consists of four steps: keyword collection, data collection, data preparation, and data analysis, as shown in Fig. 2.

During NLP, data pre-processing becomes an indispensable step, which can address the challenges posed by the noisy and unstructured nature of text posts collected from Facebook, enhancing their suitability for analysis (Benkhelifa and Laallam, 2016). Researchers increasingly discussed and implemented the process of data pre-processing for Chinese texts on social media (Xu and Guo et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2018; Chang et al., 2021). Following this research, Python was used for Chinese data cleaning after collecting the data in this study. Since it is more efficient and quicker compared to other classical methods (Dasari and Varma, 2022). This study obtained 4012 text posts after removing duplicates from the initial 4358 text posts. Additionally, invalid data, HTML tags, special characters, punctuation marks, irrelative data and redundant data from the study were excluded. In contrast to English texts, where words are readily segmented by computers using spaces and punctuation, Chinese texts lack clear word boundaries, requiring the use of specialised tokenisation techniques (Li, Meng et al., 2019; Blouin et al., 2023). Jieba, an open-source Python library, is recognised as the most widely used Chinese word segmentation tool (Lei et al., 2021). It has been applied in segmenting collected text posts into words (Lian et al., 2022). Stop words are dropped during the pre-processing step as they do not contribute to the analysis (Ravi and Ravi, 2015). It is found that the average effect of the Baidu Chinese Stop Word List is the best compared to other stop word lists to handle social media text (Xu and Qi et al., 2020). The Baidu Chinese Stop Word List 2012 was applied to remove stop words such as ‘and’, ‘the’, and ‘of’, which belong to modal particles, adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions, etc. The existing work of syntactic structure recognition relies on the effect of word segmentation and part-of-speech tagging and has a poor recognition effect on corpus without manual proofreading and limited recognition ability for low-frequency syntactic verbs in the field of NLP (Hou et al., 2021). In addition, the Chinese corpus of Malaysian Chinese is not yet mature. So, the establishment of the custom corpus is to improve the above problems and facilitate the identification of specific terms or synonyms of Chinese folk beliefs. For example, ‘Baibai’ refers to a behaviour of worship, instead of ‘goodbye’. ‘Tian Hou’ and ‘Ma Zu’ refer to the same deity. The term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) has been widely used as a document representation method, assigning a weight to each word in a document (Kim et al., 2018).

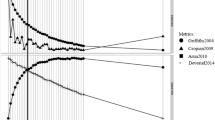

Determining the number of LDA topics is a crucial aspect of text mining. However, finding the optimal number of topics, which is essential for the success of LDA, can be tremendously challenging, especially when there is no prior knowledge about the data (Hasan et al., 2021). The topic number can be determined based on domain knowledge or by using evaluation metrics. Two commonly used methods for topic evaluation in topic models are perplexity and coherence (Santosh et al., 2019). Coherence measures the semantic similarity or interoperability of a topic model, where a higher coherence indicates better-learned topics (Hasan et al., 2021). Perplexity, on the other hand, is a widely used metric in language modelling, where a lower perplexity score indicates better generalisation performance (Anupriya and Karpagavalli, 2015). The LDA topic modelling method is implemented using the Gensim package. The Gensim implementation provides words in each topic along with their weights (Tijare and Rani 2020). In this study, the coherence model and perplexity model from Gensim were used to calculate the coherence and perplexity values. The basic strategy is to minimise the perplexity value and select the peak of coherence when determining the optimal number of topic categories (Shi and Zeng et al., 2022). Figure 3 shows that the coherence metrics reached their highest score when the number of topics was 4 and 8, while the perplexity metrics reached their lowest score when the number of topics was 3 and 4. After comprehensive consideration, topic number 4 is selected as the final number of topics for the LDA model.

To employ the LDA tool (Blei et al., 2003), this study set the number of topics as 4 and λ = 1. This allows us to generate a series of subject-word matrices based on associated sets of keywords for each topic. The corresponding Chinese characters for the top 10 terms of every topic are listed in the supplemental material (see Supplementary Table S2). Table 1 illustrates the subject-word matrix for the four topics. Each word under each topic is assigned a weight, with higher-ranking words having greater weights. The significance of distinct keywords for each subject is underscored through the examination of the semantic connections and occurrences of keywords in hashtags (Alkhodair et al., 2017).

Defining the core meaning of topics is crucial. Despite the advancements in statistical measures, the interpretability of the output is not guaranteed due to the complexity of language (Grimmer and Stewart, 2017). Therefore, when combining the subject-word matrix of each topic, it is necessary to assign artificial titles to accurately reflect the internal connection and context of the corresponding keywords. Table 2 presents the titles of four topics.

Figure 4 presents four different topics and examines their correlation. The transverse axis and longitudinal axis are represented by the principal components PC1 and PC2, respectively. The distances between topics are shown using multidimensional scaling on a 2D plane (Chuang and Ramage et al., 2012). The centres of the circles were determined by the calculated distance between topics (Blei et al., 2003). A circle represents a topic, and the larger the circle, the larger the topic. The degree of correlation between circles determines the distance from each other. The greater the degree of correlation, the closer the distance. The correlation degree between Topic 1 (Practitioners Worship) and Topic 2 (Temple Activities) is relatively strong, while Topic 4 (Merchandise about Deity Statues) has the weakest correlation with the former three topics.

Results

LDA topic modelling was utilised to systematically categorise the collected sample of comments into four distinct topics. Figure 5 meticulously depicts the top 30 relevant terms associated with each of these topics. The corresponding English translations for the top 30 most relevant terms of four topics are listed in supplemental material (see Supplementary Table S3). The word frequency distribution is normalised relative to the entire corpus by the system. The blue bar in the charts represents the overall term frequency, while the red bar signifies the estimated frequency within the context of the selected topic. In delineating the thematic content across these four topics, Topic 1, characterised by the highest proportion of text posts, commands a substantial 40.90% of the discourse. The second most is Topic 2, relating to ‘Temple Activities’, which accounts for 31.59% of the total thematic distribution. Additionally, Topic 3 and Topic 4 on the thematic dimensions of ‘Deity Legends’ and ‘Merchandise about Deity Statues’ contribute 17.38% and 10.12% respectively, further enriching the multifaceted discourse surrounding Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs.

Saliency (term w) = frequency (w) * [sum_t p(t | w)/p(t)] for topics t; see Chuang, Manning and Heer (2012). Relevance (term w | topic t) = λ * p(w | t)/p(w); see Sievert and Shirley (2014). Minor discrepancies due to rounding may cause totals to deviate slightly from 100%, without impacting the interpretation of the data.

Table 3 provides a systematic classification of the top 30 high-frequency terms, offering insights into the predominant thematic categories in Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. Topic 1 highlights the category of ‘Practices and Rituals’, which accounts for 30%. The ‘Objects’ and ‘Attributes and Functions’ categories each represent 23.30% of the Topic 1. Topic 2 reveals that ‘Practices and Rituals’ and ‘Attributes and Functions' have a substantial share of 33.30% and 30%, respectively, underscoring the central role of folk belief practices in temples. Topic 3 shows that ‘Objects’ of Chinese folk beliefs maintain their prominence, representing 43.30% of the discourse. Finally, Topic 4 showcases the significance of ‘Business and Commerce’, holding a share of 30% within the discourse of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs and ‘Religious Items’ comprise 23.30% of the thematic landscape. The ‘Objects’, ‘Practices and Rituals’ and ‘Attributes and Functions’, compared to other categories, have the highest overall proportion in the four tables. ‘Realms’ occupies a small proportion, but it is covered by Topic 1, Topic 3, and Topic 4 simultaneously, which emphasises its role as a key concept linking different topics in the overall discussion. These findings collectively contribute to a nuanced understanding of the key thematic dimensions in the discourse surrounding Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs.

Table 4 presents a compilation of high-frequency words that overlap across Fig. 5. Notably, the terms ‘Safety and Peace’ and ‘Merits and Virtues’ emerge as two keywords present in all four topics, indicating its pervasive significance. Furthermore, ‘Pray for Demands’ and ‘Consecration’ are identified as two keywords spanning three topics. Additionally, ‘Bless’, ‘Deity’, ‘Grateful’, ‘Gui Mao’, ‘Pray for Good Fortune’, ‘Bodhisattva’, ‘Become Rich’, ‘Chinese Calendar’, ‘Celebration’, ‘Millennium Birthday Celebration for a Deity’, ‘Rituals’, ‘God of Wealth’, ‘Incense Offerings’, ‘Cultivation’, ‘Increase Energy’, ‘Ma Zu’, ‘Ne Zha’, and ‘China’ are encompassed by the two topics respectively. The analysis reveals that Topic 1 and Topic 2 exhibit the highest degree of keyword overlap, sharing a total of 15 common keywords. Topic 1 and Topic 3 share six common keywords, securing the second position in terms of commonality. Topic 3 and Topic 4 share five common keywords, ranking third. Topic 2 and Topic 4 share four common keywords, which places them at the fourth rank. Topic 2 and Topic 3, as well as Topic 1 and Topic 4, each share three common keywords, which rank fifth in the keyword hierarchy. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the keywords of Topic 1 exhibit the most extensive overlap with those of other topics, suggesting a pronounced thematic connection with other topics.

Discussion

Various roles in constructing Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs

Social media communications and interactions not only facilitate the exchange of information but also serve to represent a collective identity (Jakaza, 2020). Groups representing diverse identities can thus be categorised as various types of constructors. These constructors employ their culture, language and other symbolic systems to construct meaning (Media Education Foundation, 1997). In the context of the trends of folk modernisation and secularisation, the presence of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on Facebook is quite prominent. To delve deeper into these beliefs and gain a better understanding of the information shared by social media, identifying different constructors based on different topics proves to be a valuable method. Figure 6 visually represents the contributors to the four distinct social media topics related to Malaysian Chinese society, namely practitioners, temple organisations, media organisations, and merchants. The size of each circle reflects the level of engagement with different topics on Facebook, with larger circles indicating a wider range of thematic content.

The engagement levels of different groups on social media are as follows: practitioners exhibit the highest level of engagement, followed by temple organisations, merchants, and media organisations. There is a significant overlap in the content posted by these groups. For example, both practitioners and media organisations discuss ‘Practitioners Worship’ practices, particularly within the temple. Similarly, ‘Temple Activities’ are commonly discussed by temple organisations, practitioners, and media organisations. ‘Deity Legends’ emerge as a recurrent theme among temple organisations, practitioners, and merchants, while ‘Merchandise about Deity Status’ is disseminated by merchants, with practitioners and temples being the demand side and merchants being the supply side. Practitioners play a crucial role in forming virtual communities on social media platforms, where they share their folk beliefs through personal experiences, rituals, prayer demands, and belief objects. Temple organisations strengthen their connection with practitioners by using social media to disseminate ceremonies and activities and promote temple culture. Media organisations utilise social media platforms to broadcast news, reports, and features related to Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. Merchants, on the other hand, are seen as suppliers who provide religious products to meet the demands of practitioners and temples, thus popularising the symbols and cultural significance of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. The interactive and communicative activities of these four groups on social media create a diverse and dynamic network, contributing to the cross-regional spread and understanding of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. The extensive reach of social media surpasses geographical and national boundaries, enabling a broader spread of folk beliefs among Malaysian Chinese individuals. This method of sharing information differs significantly from traditional, offline methods of dissemination, which are often restricted by geographic constraints and typically limited to specific communities or regions.

Characteristics of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs

After identifying the constructors and content themes of construction, the interaction with social media allows us to observe the inherent characteristics of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs as they are presented in the virtual world. These characteristics reflect the real world and are continuously constructed and reshaped through the ongoing interaction among these three factors. From the categorisation presented in Table 3, the characteristics of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs are observable. This study focuses on explaining the following categories: ‘Attributes and Functions’, ‘Objects’, ‘Practices and Rituals’, ‘Charity and Donations’, and ‘Realms’. Additionally, the study discusses other characteristics, including the influence of Taoism in Topic 3, the practice of merchandise within the context of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs in Topic 4, and the relationship between Chinese folk beliefs and the Spring Festival as illustrated in Tables 3 and 4. Furthermore, Table 4 elucidates the interconnected semantic nexus based on ‘Safety and Peace’, ‘Pray for Demands’, and ‘Merits and Virtues’.

In examining the four central themes related to ‘Attributes and Functions’ within the context of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs, it becomes clear that these beliefs are characterised by a utilitarian approach. Deities in this framework are primarily seen as beings to be appeased and propitiated. The interaction with the divine typically involves sacrificial rituals, serving both material and spiritual purposes. Malaysian Chinese practitioners engage with deities through various rituals, ceremonies, and performances, establishing a reciprocal relationship with these spiritual entities. In their pursuit of prosperity, safety, and vitality, individuals believe that these practices can bring tangible benefits like ‘Become Rich’, ‘Safety and Peace’, and ‘Increase Energy’. ‘Pray for Good Fortune’ and ‘Pray for Demands’ are not just specific expressions of faith; more importantly, they reflect the hopes, fears, and visions inherent in a belief system. These commitments to deity worship are seen as a pragmatic investment aimed at fulfilling specific worldly requests. Similar to Fei’s observations (1985), this form of worship combines hosting, communication, and even bribery of the divine. Prayers in this context resemble wishes and pleas, where the deities are seen not as ideals or moral judges but as potent sources of material wealth and power.

Under the ‘Objects’ category, Chinese deities exhibit distinct regional characteristics and godhood. This demonstrates a reciprocal interaction pattern that is heavily influenced by utilitarianism. The Malaysian Chinese community assigns practical functions to the deities they worship. For example, ‘Ma Zu’, originally revered as a sea goddess in Fujian and Hainan areas, has evolved beyond her initial role as a guardian of the sea. She is now a multifaceted deity responsible for averting plagues, and pests, influencing weather patterns, and providing healing. ‘God of Wealth’, primarily worshipped by the merchant class who historically held high social status and influence due to their wealth in the early stages of immigration (Yee, 2000). Compared to Chinese residents in China, the Malaysian Chinese community places a greater emphasis on the pursuit of wealth accumulation and social prestige, thereby reinforcing the tradition of worshipping this deity. Additionally, ‘Datuk Gong’ represents an interesting fusion of Chinese and Malay cultural elements, embodying the hopes of the Malaysian Chinese community for blessings and protection within the territorial boundaries of the Malay Peninsula. Notably, there is a significant influence of Hokkien folk deities within the Malaysian Chinese community. Deities such as ‘Ma Zu’, ‘Ne Zha’, ‘Wang Ye’, ‘Xuan Tian Shang Di’, ‘Bao Sheng Da Di’, and ‘Guang Ze Zun Wang’ represent the prevalent folk beliefs among the Hokkien ethnic group. They are frequently cited under the deity category, highlighting their prominence in comparison to the deities worshipped by other Malaysian Chinese ethnic groups.

The categories of ‘Practices and Rituals’ and ‘Charity and Donations’ within the research shed light on the intricate social functions and activities inherent in Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. Temples, traditionally regarded as central hubs in the Chinese community, serve as venues for collective interactions, engagement in folk belief practices, and broader social involvement, thus fostering community cohesion and a spirit of collective support. Primarily, these temples organise a wide range of blessing ceremonies, including ‘Rituals’, ‘Consecration’, ‘Lighting Lamps’, ‘Worship’, ‘Celebration’, and ‘Incense Offerings’. These ceremonies, which attract participants from both within and outside the community, aim to seek divine protection and blessings for devotees. Secondarily, financial contributions are essential for the sustainability of temple operations and their associated activities. Devotees contribute through various means, such as ‘Donations’, ‘Financial Support’, and temples frequently hold ‘Fundraising’ initiatives to generate revenue. The management of temple affairs, including the maintenance of temple infrastructure and provision of community services, heavily relies on these financial inflows. Lastly, temple organisations act as social hubs, facilitating a diverse array of activities such as ‘Banquet’, ‘Competition’, ‘Millennium Birthday Celebration for a Deity’, ‘Lion Dance’, and ‘Pageant on Immortals’. These events not only enhance mutual understanding among community members but also play a vital role in establishing strong social networks. As articulated by Yang (1961), the essence of these practices and rituals lies in their ability to invoke celestial authority, thus serving a crucial role in upholding the moral fabric of society.

Within the ‘Realms’ category, the realm of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media presents two flowing realms. The first is the flowing realm of deities. The deity statues mainly come from ‘China’, ‘Taiwan’, and ‘Thailand’, flowing to ‘West Malaysia’ and ‘East Malaysia’. This transnational flow serves not only as a medium of cultural transmission but also as a bridge connecting different regions and cultures. For example, the Malaysian International Guan Gong Culture Festival, where Malaysian Chinese carry the statue of Guan Gong from Guan Gong temples in China for a procession, attracts nearly a hundred thousand participants. It not only facilitates folk interaction between Malaysia and China but also promotes local commerce and tourism in Malaysia. It can be observed that religious events play an important role in promoting tourism in areas where it is held (Olsen and Timothy, 2006). The second is the flowing realm of participants. The top keywords, such as ‘Ancient Temples’ and ‘Penang’ on Facebook, reveal the preference of Malaysian Chinese for ancient temples and Penang. Religious tourism can influence tourist behaviour and travel destination choices (Noga, 2018). Locals visit ancient temples largely because of their efficacy. These temples attract foreign tourists with their unique architectural styles and rich religious and cultural backgrounds. For instance, the Kuala Lumpur Guan Di Temple and Johor Ancient Temple are not only centres of faith but also tourist attractions. ‘Penang’ is the state with the highest proportion of Chinese residents. The local temple fair during the Spring Festival is especially rich, showcasing a strong cultural atmosphere and Chinese community participation. Participants engage in religious activities and share their experiences on Facebook, leveraging the platform’s reach to attract more people to visit temples or regions and partake in these events. Thus, it is evident that the role of social media in promoting religious tourism is indispensable (Cristea et al., 2015).

Topic 3 explores the widespread influence of Taoism, a significant aspect of Chinese religion, on the legends of deities within the Malaysian Chinese community. These legends depict the concepts of ‘Cultivation’ and ‘Manifestation’ associated with these deities. Some of these deities, like ‘Bao Sheng Da Di’ and ‘Xuan Tian Shang Di’, are considered part of ‘Taoism’. According to Xu (2010), Taoism goes beyond Confucian thought and encompasses a broader range of spiritual and cultural aspects. It assimilates and transforms certain elements of Chinese folk beliefs, which then deeply impact the folk beliefs themselves. Taoism actively incorporates Chinese folk deities into its pantheon, enriching its mythological collection with characters such as ‘Guan Gong’ and ‘Ma Zu’, among others. This infusion of Taoist elements gives Chinese folk beliefs a strong Taoist influence (Li and Liu et al., 2011). Customs like worshipping ‘Tai Sui’, offering sacrifices to ancestors through burning paper money, paying homage to the king of the stove, displaying couplets, and welcoming the ‘God of Wealth’, all have their origins in Taoism (Li and Liu et al., 2011). Moreover, Taoist beliefs have not only permeated religious practices but also influenced various cultural customs within Malaysian Chinese society. For example, the belief in ‘Manifestation’ from deities is reflected in traditional medical practices and Feng Shui. Malaysian Chinese believe that through belief practices such as drinking talisman water or placing specific items, deities can improve their lives or cure diseases via some mysterious power. In conclusion, the integration of Taoist elements into Malaysian Chinese deity legends and cultural practices highlights the profound impact of this religious tradition on the community’s belief systems and daily life.

Topic 4 explores the commercialisation of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social platforms. The phenomenon of beliefs economy has been prevalent in China since the Song dynasty and emerged in Malaysia’s Chinese community during the 18th and 19th centuries. Today, social media provides a contemporary outlet for merchants, allowing them to reach a wider customer base without geographical limitations. These platforms offer detailed descriptions of ‘Deity Statues’, including information on materials, design styles, dimensions, purchasing methods, and prices. For example, the use of ‘Camphor Wood’ and ‘Wood Carvings’ in crafting these statues showcases traditional artistry. The statues primarily originate from ‘China’, ‘Taiwan’, and ‘Thailand’. ‘Deity Statues’ in the market, including ‘Da Er Ye Bo’, ‘Ma Zu’, and ‘Ne Zha’, are more popular compared to others. The online sale of ‘Deity Statues’ has been witnessed in both ‘West Malaysia’ and ‘East Malaysia’, highlighting the digital extension of the deity economy. Therefore, the commercialisation of ‘Deity Statues’ through social media serves as a contemporary manifestation of the deity economy, showcasing the significant intersection between religious practice and modern commerce.

Tables 3 and 4 provide a detailed analysis of the intricate relationship between Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs and the Spring Festival. These tables demonstrate how important the concept of time is within a particular set of cultural systems, reflecting a strong connection to traditional Chinese calendars, beliefs and festivals. For example, the practice of ‘Ancestor’ worship during the Spring Festival not only reflects the Confucian value of filial piety, which is fundamental in Chinese society, but also symbolises the desire to receive ancestral blessings of peace, health, and prosperity in the coming year. Reference to ‘Gui Mao’, which corresponds to the year of the rabbit. ‘Gui Mao’, ‘Chinese Calendar’, and ‘The First Lunar Month’ particularly emphasise the fusion with time. Chinese temples play a central role in the celebration of the Spring Festival, transforming into community hubs where people gather, communicate, and partake in festive activities. The sacred nature of the festival disrupts daily routines (Zhao, 2017), leading to an increased number of individuals visiting temples to show reverence to deities. During this festival period, there is a heightened participation in religious rituals, such as the practices of ‘Worship’ and ‘Incense Offerings’ which are believed to influence the upcoming year. Temples actively promote specific Spring Festival activities, including ‘Lighting Lamps’, ‘Lion Dance’, and ‘Pageant on Immortals’, with the aim of engaging the Chinese community. Furthermore, certain customs observed during the Spring Festival reflect deeply ingrained Chinese folk beliefs. In traditional Chinese culture, the ‘Zodiac’ symbolises different animals and is closely associated with one’s birth year, assigning each individual to a specific zodiac sign. Each year is governed by a ‘Tai Sui’, who is believed to oversee the fortunes and auspicious events of that year. During the Spring Festival, there is a heightened emphasis on the relationship between an individual’s zodiac sign and the reigning ‘Tai Sui’. To mitigate any potential negative influence from ‘Tai Sui’, many people seek refuge in temples and participate in activities specifically designed to overcome adversities. The Malaysian Chinese community combines this conscientiousness with traditional rituals and celebrations, collectively seeking blessings for good fortune and happiness in the upcoming year.

Table 4 presents the three key concepts with the highest overlap—‘Safety and Peace’, ‘Pray for Demands’, and ‘Merits and Virtues’—which all belong to the category of ‘Attributes and Functions’ and form an interconnected semantic nexus in the context of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. These concepts interact dynamically, creating a cycle of positivity in Chinese folk belief practices, as illustrated in Fig. 7. In the context of Malaysian Chinese culture, the motivation to participate in belief-based activities stems from the concept of ‘Pray for Demands’. Through these activities, individuals can directly communicate their wishes and needs to a higher power or spiritual entities, providing psychological support, especially during challenging times. Practitioners express their reliance on the divine for blessings that lead to mental peace and material well-being. Traditionally, ‘Merits and Virtues’ represent the accumulation of moral wealth through virtuous actions and positive behaviour. The accrual of good deeds or moral excellence is considered a practice that brings positivity and benefits not only to the individual but also to the broader community. The concept of ‘Safety and Peace’, highly valued within this belief system, symbolises the aspiration for tranquillity and security at individual, familial, and societal levels, reflecting a deep-seated yearning for stability and contentment in life. Practitioners engage in praying for demands at temples through two distinct modalities. One is physical, manifesting in the performance of meritorious acts that sometimes involve purchasing religious items as offerings to the deities. Practitioners may participate in visible acts of merit, such as lighting incense, burning paper offerings, and making donations, all while coupling these actions with heartfelt prayers. The other is spiritual, characterised by internal expressions of worship. While the physical deeds are overt and observable, the inwardly directed practices remain a private and invisible aspect of their spiritual practice. Merchandise includes both practitioners purchasing religious items and temples selling them. These items are intended for deities or to aid the poor and the sick. Practitioners acquire ‘Merits and Virtues’ through acts of charity, donations, and support for religious institutions. There is a belief that accumulating more ‘Merits and Virtues’ increases divine assistance in fulfilling wishes. This interplay highlights the profound significance of these concepts in religious practices. Practitioners often begin with a desire for ‘Safety and Peace’, which leads them to ‘Pray for Demands’ in pursuit of divine blessings. By engaging in these physical acts, practitioners aim to establish a connection with the deities and seek assistance, blessings, or guidance. Deities, as spiritual beings, are often believed to provide mysterious powers to intervene in practitioners’ lives in the process of responding to the heartfelt prayers and devotion of practitioners. These interventions are often invisible. Outwardly, practitioners demonstrate their merits through donations, acquiring religious items, and participating in ceremonies like dharma meetings or blessing events. Internally, these reciprocal exchanges are the implicit manifestation of practitioners engaging with temples and deities. Thus, in their pursuit of divine help, practitioners engage in ‘Praying for Demands’ as a means to establish a connection with the deities. Under the influence of a mutual exchange, they aim to meet their spiritual aspirations by amassing ‘Merits and Virtues’ in temples, thereby securing ‘Safety and Peace’ in their lives. This integrative framework forms a comprehensive belief ecosystem, intertwining individual aspirations, ritualistic expressions of belief, and the resulting spiritual feedback, thus encompassing a holistic approach to spiritual fulfilment.

There are two aspects of contemporary significance in this semantic nexus. The identity of Malaysian Chinese functions as a key pillar compared with other groups. Individuals within the Chinese community have the opportunity to embrace their unique religious traditions and practice shared values, fostering a deep sense of belonging and unity within their community. On the other hand, the pursuit of ‘Merits and Virtues’ often translates into acts of charity and social service. It is a widespread phenomenon that numerous devout practitioners and Chinese temple organisations are very willing to care for the elderly and the poor without racial bias. This can contribute to the establishment of philanthropic efforts that bolster friendly ties among different racial communities. Based on the above content, two future trends in Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media can be predicted. To begin with, the role of temples will continue to be reinforced. As modernity challenges traditional practices, the popularity of social media has not reduced participants’ involvement in temples but will further reinforce the spatial function of temples, such as providing a spiritual space for people and cultivating a physical space for interaction and identity affirmation. Another aspect, the commercialisation and charitable activities of temples will continue, as these are seen as representations of doing ‘Merits and Virtues’. An increasing number of Malaysian Chinese are likely to not only be willing to pay for such commercialisation but also to participate in the charitable activities of temples in the future.

Conclusions

In the investigation of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs during the 2022 Spring Festival, this study focused on analysing Facebook text posts, through which four main thematic categories were identified: ‘Practitioners Worship’, ‘Temple Activities’, ‘Deity Legends’, and ‘Merchandise about Deity Statues’. Highlighting the significant role played by practitioners, temple organisations, media organisations, and merchants in shaping and spreading Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs through social media. Further analysis shows that these beliefs possess significant utilitarianism, regional diversity, multiple social functions, flowing realms, strong Taoist elements, commercialisation, and a close relationship with the Spring Festival. Additionally, a robust semantic network was discovered on social media, linking concepts of ‘Safety and Peace’, ‘Pray for Demands’, and ‘Merits and Virtues’. The chain link that places emphasis on mystery and ritual within Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs is being diluted through the widespread and open dissemination channels of social media. Importantly, the increasing diversity of constructors indicates a rise in Malaysian Chinese folk belief-related content on these platforms. The surge in content variety reflects a vibrant and evolving digital landscape where Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs are not only preserved but also creatively reinterpreted and integrated into modern life. As the digital footprint of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs expands, the interaction among social media platforms, constructors, and content is continually strengthened in the virtual world. This demonstrates that social media serves as a catalyst for both the continuity and innovation of Chinese folk beliefs in Malaysia. The ease with which these beliefs adapt to the digital medium highlights the resilience and dynamism of Malaysian Chinese religious culture.

Limitations

This study contributes to the understanding of Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on social media platforms. Due to the unavailability of data authorisation for scraping Facebook from the official CrowdTangle website, we manually collected Facebook data, specifically focusing on text posts related to active deities. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge the restrictions of our investigation. The analysis of comments using LDA has its inherent limitations, particularly when dealing with a small number of comments or extremely short comments (Tang et al., 2014). Moreover, the material in the form of images and short clips from platforms such as TikTok, which are popular with the younger generation, may have been overlooked. In addition, Sentiment analysis is being increasingly employed to automatically detect positive or negative emotions in text reviews (Nur and Suryanti, 2021). The following three suggestions could further improve the quality of this study. First, in terms of research methodology, adding fieldwork could provide more empirical cases to validate the text posts on social media. Second, expanding the content scope to incorporate the analysis of images and videos would align more closely with the current trend of content videoisation on social media. Third, adding sentiment analysis could help identify participants’ emotional tendencies towards Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. These enhancements can encourage future research to focus on strategies for leveraging social media to enhance cultural dissemination and cultural identity among Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs. They may also address the challenges of religious commercialisation and religious tourism.

Data availability

The datasets generated by the survey research during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the Dataverse repository, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ODIQMN.

References

Adoni H, Mane S (1984) Media and the social construction of reality: toward an integration of theory and research. Commun. Res. 11(3):323–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365084011003001

Alan EG (2000) Gibbs sampling. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 95(452):1300–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2000.10474335

Alkhodair SA, Fung BCM, Rahman O, Hung PCK (2017) Improving interpretations of topic modeling in microblogs. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 69(4):528–540. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23980

Anderson B, Fagan P, Woodnutt T, Chamorro-Premuzic T (2012) Facebook psychology: popular questions answered by research. Psychol. Pop. Media Cult. 1(1):23–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026452

Anupriya P, Karpagavalli S (2015) LDA based topic modeling of journal abstracts. Paper presented at 2015 International Conference on Advanced Computing and Communication Systems, Coimbatore, India, pp.1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACCS.2015.7324058

Barde BV, Bainwad AM (2017) An overview of topic modeling methods and tools. Paper presented at 2017 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, pp.745–750

Benkhelifa R, Laallam FZ (2016) Facebook posts text classification to improve information filtering. Paper presented 12th International Conference on Web Information Systems and Technologies (WEBIST), Rome, Italy, pp. 202–207. https://doi.org/10.5220/0005907702020207

Berger PL, Luckmann T (1966) The social construction of reality: a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Doubleday & Company, New York

Blei DM, Ng AY, Jordan MI (2003) Latent dirichlet allocation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 3(1):993–1022

Blouin B, Huang HH, Henriot C, Armand C (2023) Unlocking transitional Chinese: word segmentation in modern historical texts. Paper presented at the Joint 3rd International Conference on Natural Language Processing for Digital Humanities and 8th International Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Uralic Languages, Tokyo, Japan, pp. 92–101

Carr CT, Hayes RA (2015) Social media: defining, developing, and divining. Atl. J. Commun. 23(1):46–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2015.972282

Chang D, Cui L, Sun Y (2021) Mining and analysis of emergency information on social media. In: Liu S, Bohács G, Shi X, Shang X, Huang A (eds). LISS 2020. Springer, pp. 627–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4359-7_44

Chen JX (2010) Haiwai huaren zongjiao wenshu yu wenhua chuancheng: xinma dejiao zixi wenxian 1947-1966 (Religious texts and cultural heritage of overseas Chinese: Dejiao zixi literature in Singapore and Malaysia 1947–1966). Social Sciences Academic Press, Beijing (In Chinese)

Chen SR (2022) Yiqing xia de chunjie: “Fei zhengchang” shiduan de “Fei richang” shenghuo: yi 2020 nian Sichuan Qionglai Nanting xiaoqu weili (The Spring Festival during the Covid-19: “Non-normal” times and “non-daily” life: a case study of the Nanting community in Qionglai, Sichuan in 2020). Festiv. Stud. 2022(19):152–170 (In Chinese)

Chen YL (1999) Shilin guangji (Vast record of varied matters). Zhonghua Book Company. p.481 (In Chinese)

Cheng CM (2006) Chuantong zongjiao de chuanbo (The spread of traditional religions). Dayuan Books, Taibei (In Chinese)

Cheu HT (1982) An analysis of the nine emperor gods spirit-medium cult in Malaysia. Cornell University, New York

Choo CT (1968) Some sociological aspects of Chinese temples in Kuala Lumpur. Dissertation (M.A.). Faulty of art and social science, Universiti Malaya (In Chinese)

Chuang J, Manning C, Heer J (2012) Termite: visualization techniques for assessing textual topic models. Proceedings of the International Working Conference on Advanced Visual Interfaces, Capri Island, pp. 74–77. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/2254556.2254572

Chuang J, Ramage D, Manning C, Heer J (2012) Interpretation and trust: designing model-driven visualizations for text analysis. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Austin, Texas, pp. 443–452. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2207676.2207738

Cristea AA, Apostol MS, Dosescu T (2015) The role of media in promoting religious tourism in Romania. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 188:302–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.03.398

Dasari D, Varma PS (2022) Data cleaning techniques using Python. AKNU J. Sci. Technol. 1(1):11–21

Datareportal (2023) Digital 2023:Malaysia. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2023-malaysia. Accessed 21 Sept 2023

Fei XT (1985) Meiguo he meiguoren (American and Americans). Sanlian Bookstore, Shanghai. p.110 (In Chinese)

Gamaleri G (2019) Media ecology, Neil Postman’s legacy. Church, Commun. Cult. 4(2):238–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/23753234.2019.1616585

Gergen KJ (1985) The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. Am. Psychol. 40(3):266–275

Griffiths TL, Steyvers M (2004) Finding scientific topics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101(suppl 1):5228–5235. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0307752101

Grimmer J, Stewart BM (2017) Text as data: the promise and pitfalls of automatic content analysis methods for political texts. Polit. Anal. 21(3):267–297. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mps028

Han WT (1939) Da Bo Gong de yanjiu (The study of Da Bo Gong). Sin Chew Daily. December 19 (In Chinese)

Hasan M, Rahman A et al. (2021) Normalized approach to find optimal number of topics in latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA). In: Kaiser MS et al. (eds). Proceedings of International Conference on Trends in Computational and Cognitive Engineering. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 1309. Springer, Singapore, pp.341–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-33-4673-4_27

Hou WH, Qu WG, Wei TX, Li B, Gu YH, ZHou JS (2021) Construction of a concurrent corpus for a Chinese AMR annotation system and recognition of concurrent structures. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 61(9):920–926. (In Chinese) http://jst.tsinghuajournals.com/EN/Y2021/V61/I9/920

Hsu YT (1951) Da Bo Gong, Er Bo Gong Yu Ben Tou Gong (Da Bo Gong, Er Bo Gong and Ben Tou Gong). J. South Seas. Soc. 7(2):6–10. (In Chinese)

Hue GT, Wei KK et al. (2023) The Malaysian historical geographical information system (MHGIS): the case of Chinese temples in Johor. Religions 14(3):336. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14030336

Jelodar H, Wang Y et al. (2019) Latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA) and topic modeling: models, applications, a survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78(11):15169–15211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-018-6894-4

Jenkins H (2006) Convergence culture: where old and new media collide. NYU Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qffwr

Jakaza E (2020) Identity construction or obfuscation on social media: a case of Facebook and WhatsApp. Afr. Identities 20(1):3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725843.2020.1804829

Kenneth D (2021) Malaysia historical geographical information system, “MHGIS”: a study of Chinese associations and temples in Malaysia. In: Khoo KU, Chiang BW(eds). Selected papers on the Fifth Biennial International Conference on Malaysian Chinese Studies, 2021. Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies, Kuala Lumpur. pp.3–15 (In Chinese)

Kent ML (2010) Directions in social media for professionals and scholars.In: Heath RL (ed). Handbook of public relations (2nd): pp. 643–656. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Kim D, Seo D et al. (2018) Multi-co-training for document classification using various document representations: TF–IDF, LDA, and Doc2Vec. Inf. Sci. 477(2019):15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ins.2018.10.006

Lei Q, Li HF, Wei RB (2021) Leveraging Zipf’s law to analyze statistical distribution of Chinese corpus. Paper presented at 2021 IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Artificial Intelligence (SEAI), Xiamen, China, pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/SEAI52285.2021.9477550

Lewis BK (2010) Social media and strategic communication: attitudes and perceptions among college students. Public Relat. J. 4(3):1–23

Li X, Meng Y, Sun X, Han Q, Yuan A, Li J (2019) Is word segmentation necessary for deep learning of Chinese representations? Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. Florence, Italy, pp. 3242– 3252. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P19-1314

Li YG, Liu ZY et al. (2011) Daojiao yu minjian xinyang (Taoism and folk beliefs). Shanghai People’s Publishing House, Shanghai (In Chinese)

Li YY (1997) Xin xing zongjiao yu chuantong yishi: yige renleixue de kaocha (Emerging religions and traditional rituals: An anthropological investigation). Ideol. Front. 1997(3):41–46. (In Chinese)

Lian Y, Zhou Y et al.(2022) Cyber violence caused by the disclosure of route information during the COVID-19 pandemic Human. Soc. Sci. Commun. 417:29–45. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01450-8

Lu Y (2010) Zhongguo chuantong shehui minjian xinyang zhi kaocha (An investigation of traditional Chinese folk beliefs). Wen Shi Zhe 2010(4):82–95. (In Chinese)

Lu Y (2012) Zhongguo minjian xinyang yanjiu pingshu (Research review of Chinese folk beliefs). Shanghai People’s Publishing House, Shanghai. p.3 (In Chinese)

Mak LF (2017) The virtual triad societies in early Malaya. Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies, Kuala Lumpur. p.4 (In Chinese)

Media Education Foundation (1997) Representation & the media. https://www.mediaed.org/transcripts/Stuart-Hall-Representation-and-the-Media-Transcript.pdf. Accessed 29 Feb 2024

McLuhan M (1964) Understanding media: the extensions of man. McGraw-Hill

Noga CK (2018) Pilgrimage-Tourism: common themes in different religions. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 6(1):8–17. https://doi.org/10.21427/D73428

Nur SMN, Suryanti A (2021) An enhanced hybrid feature selection technique using term frequency-inverse document frequency and support vector machine-recursive feature elimination for sentiment classification. IEEE Access 9(0):52177–52192. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2021.3069001

Olsen DH, Timothy DJ (2006) Tourism, religion and spiritual journeys (vol.4). Routledge, London. pp.1-21

Papacharissi Z (2022) Affective publics: solidarity and distance. In: Deana AR and Sarah S(eds). The Oxford Handbook of Digital Media Sociology (2022; online edn, Oxford Academic, 8 Oct. 2020). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197510636.013.6. Accessed 16 Mar. 2024

Ravi K, Ravi V (2015) A survey on opinion mining and sentiment analysis: tasks approaches and applications. Knowl. Based Syst. 89(2015):14–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.knosys.2015.06.015

Reese SD, Oscar HG, August EG (2001) Framing public life: perspectives on media and our understanding of the social world. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ

Santosh KR, Amir A et al. (2019) Review and implementation of topic modeling in Hindi. Appl. Artif. Intell. 33(11):979–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2019.1661576

Shi WZ, Zeng F et al.(2022) Online public opinion during the first epidemic wave of COVID-19 in China based on Weibo data. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 9:159. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01181-w

Sievert C, Shirley K (2014) LDAvis: a method for visualizing and interpreting topics. Proceedings of the Workshop on Interactive Language Learning, Visualization, and Interfaces. Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 63–70. https://doi.org/10.3115/v1/W14-3110

Soo KW (1997) A study of the I-Kuan Tao (unity sect) and its development in peninsular Malaysia. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of British Columbia

Soo KW (2012) Dongnanya huaren minjian zongjiao yanjiu zongshu (A survey of the study of Chinese folk religion in Southeast Asia). In: Lu Y(ed). Zhongguo Minjian Xinyang Yanjiu Zongshu (A Review of Research on Chinese folk beliefs). Shanghai People’s Publishing House, Shanghai. p.314 (In Chinese)

Su KS, Chen SZ (2010) Photographic compilation of hundred years’ divine procession of the Johor old Chinese temple. Management Committee of the Johor Old Chinese Temple (In Chinese)

Tan CB (1985) The Development & distribution of Dejiao associations in Malaysia and Singapore: a study on a Chinese religious organization. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

Tan CB (2014) Ancestral god, locality god, and Chinese transnational pilgrimage. In:Tan CB (ed). After Migration and Religious Affiliation: Religions, Chinese Identities and Transnational Networks. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd, Singapore. p.356

Tan YS (1952) Tian Fei kaoxinlu (Historical research on the Tian Fei). J. South Seas. Soc. 8(2):29–32. (In Chinese)

Tang J, Meng Z et al. (2014) Understanding the limiting factors of topic modeling via posterior contraction analysis. Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Machine Learning 32(1)):190–198. PMLR

Tijare P, Rani PJ (2020) Exploring popular topic models. J. Phys. 1706 (2020) 012171. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1706/1/012171

Wang YN (2017) Convergence rates of latent topic models under relaxed identifiability conditions. Electron. J. Stat. 13(1):37–66. https://doi.org/10.1214/18-EJS1516

Wohn DY and Bowe BJ (2014) Crystallization: how social media facilitates social construction of reality. In: Fussell SR, Lutters WG, Morris MR, Reddy M(eds). Proceedings of the Companion Publication of the 17th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing. CSCW Companion, NY, USA, pp. 261–264. https://doi.org/10.1145/2556420.2556509

Wolfgang F, Chen TF (1982) Chinese epigraphic materials in Malaysia (volume 1). University of Malaysia Press, Kuala Lumpur

Xu A, Qi T, Dong X (2020) Analysis of the Douban online review of the MCU: based on LDA topic model. J. Phys. 1437(2020) 012102. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1437/1/012102

Xu DS (2010) Daojiao shi (The history of Taoism). Phoenix Publishing House, Nanjing (In Chinese)

Xu S, Guo J and Chen X (2016) Extracting topic keywords from Sina Weibo text sets. Proceedings of 2016 International Conference on Audio, Language and Image Processing (ICALIP). Shanghai, China, pp. 668–673. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALIP.2016.7846663

Yang CK (1961) Religion in Chinese society: a study of contemporary social functions of religions and some of their historical factors. University of California Press, Berkeley

Yee CH (2000) Historical background. In: Lee KH, Tan CB (eds). The Chinese in Malaysia. New Oxford University Press,York. pp.28–30

Zhang L, Wu Z, Bu Z, Jiang Y, Cao J (2018) A pattern-based topic detection and analysis system on Chinese tweets. J. Comput. Sci. 28(2018):369–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocs.2017.08.016

Zhao SY (2017) Kuanghuan yu richang—Ming Qing yilai de miaohui yu minjian shehui (Carnival and daily life: temple fairs and local society since the Ming and Qing dynasties). Peking University Press, Peking (In Chinese)

Zhao W, Chen JJ et al. (2015) A heuristic approach to determine an appropriate number of topics in topic modeling. BMC Bioinforma. 16(Supp113):S8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-16-S13-S8

Zhao X, Lampe C, Ellison NB (2016) The social media ecology: user perceptions, strategies and challenges. Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. San Jose, CA, USA, pp. 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1145/2858036.2858333

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: HN, HKC and FPS Methodology and theory: HN Analysis and interpretation of results: HN, HKC and FPS Original draft and editing: HN Draft review: HN and HKC All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, N., Ho, K.C. & Fan, P.S. Malaysian Chinese folk beliefs on Facebook based on LDA topic modelling. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 547 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03066-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03066-6