Abstract

Study design:

Prospective cohort study.

Objective:

To assess functional hindrance due to spasticity during inpatient rehabilitation and 1 year thereafter in individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) and to determine factors that influence the hindrance.

Setting:

Eight specialized rehabilitation centres in the Netherlands.

Methods:

A total of 203 patients with recent SCI rated the hindrance they perceived due to spasticity in daily living at the start of active rehabilitation (t1), 3 months later (t2), at discharge (t3) and 1 year after discharge (t4). Hindrance was dichotomized into absent or negligible and present. Multilevel regression analyses were performed to determine the course of functional hindrance due to spasticity and its associations with possible determinants—namely, age, gender, cause, lesion level, motor completeness, spasticity and anti-spasticity medication.

Results:

The percentage of individuals that indicated functional hindrance due to spasticity ranged from 54 to 62% over time and did not change significantly over time (Δt3t1 odds ratio (OR)=0.85, P=0.44; Δt3t2 OR=1.20, P=0.41; Δt3t4 OR=0.91, P=0.67). The percentage of individuals who experienced a lot of hindrance due to spasticity during specific activities ranged from 4 to 27%. The odds for experiencing functional hindrance due to spasticity were significantly higher for individuals with tetraplegia (OR=2.17, P=0.0001), more severe spasticity (OR=5.51, P<0.0001) and for those using anti-spasticity medication (OR=4.18, P<0.0001).

Conclusion:

Functional hindrance due to spasticity occurred in the majority of persons with SCI and did not change significantly during inpatient rehabilitation and 1 year thereafter. Factors that influence hindrance were determined.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spasticity is defined as ‘disordered sensori-motor control, resulting from an upper motor neuron lesion, presenting as intermittent or sustained involuntary activation of muscles’.1 The literature has shown that 65–78% of individuals with chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) have symptoms of spasticity.2, 3 It has the potential to negatively influence the quality of life through restricting activities of daily living, causing pain and contributing to the development of contractures.4, 5

In a sample of SCI survivors, the prevalence of problematic spasticity at 1, 3 and 5 years following SCI was 35%, 31% and 27%, respectively.5 These findings agree with the observations of Levi et al.6 and Sköld et al.3 Adriaansen et al.7 reported problematic spasticity in 28–34% of individuals with SCI 1–5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. However, these studies do not describe how hindrance due to spasticity develops in the early phase after SCI. More knowledge is necessary about the course of hindrance over time and which activities of daily living are most hindered by spasticity in order to improve the management of spasticity.

The aim of the present study was to describe functional hindrance due to spasticity during inpatient rehabilitation and 1 year thereafter in individuals with SCI and its associations with possible determinants.

Materials and methods

Participants

Data used for the present study were collected in a standardized manner as part of the prospective cohort study ‘Physical strain, Work Capacity and Mechanisms of Restoration of Mobility in the Rehabilitation of Persons with Spinal Cord Injuries’.8 Between August 2000 and July 2003 individuals with an acute spinal cord lesion admitted to one of the eight participating rehabilitation centres in The Netherlands were included. Inclusion criteria were age 18–65 years, presence of tetraplegia or paraplegia, ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) Impairment Scale (AIS)9 A–D and some degree of wheelchair dependency. Exclusion criteria were progressive disease, mental disease restricting good participation and poor understanding of the Dutch language.

Procedure

Participants were assessed according to a standardized protocol, including a medical assessment, functional tests and self-report questionnaires. Measurement occasions were at the start of active rehabilitation, defined as the moment when the participant was able to sit in a wheelchair for ⩾3 h (t1), 3 months later (t2), at discharge (t3) and 1 year after discharge (t4). The protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Stichting Revalidatie Limburg and the Institute for Rehabilitation Research. All participants gave their written informed consent before participation.

Measurements

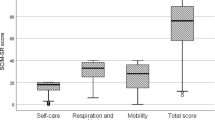

Functional hindrance due to spasticity

Hindrance due to spasticity was assessed with a subjective rating scale for each of the following activities: (1) sleeping; (2) making transfers; (3) washing and clothing; (4) wheelchair driving; (5) ‘others’. The scale ranged from 0 to 2 (0: no hindrance due to spasticity; 1: little hindrance due to spasticity; 2: a lot of hindrance due to spasticity). A sum score for hindrance during all activities was calculated. It ranged from 0 (no hindrance) to 10 (a lot of hindrance during all activities). For the statistical analyses this sum score was dichotomized into two groups: (1) no hindrance at all or a little hindrance during only one activity (sum score 0 and 1) and (2) more hindrance (sum score 2–10).

Determinants

The following demographical data were registered: age, gender, cause of SCI, time since SCI, AIS scores and lesion level.

Completeness of SCI was dichotomized as motor complete (AIS A and B) and motor incomplete (AIS C and D). Lesion level was divided into tetraplegia and paraplegia. Tetraplegia was defined as a lesion at or above the first thoracic segment, and paraplegia as a lesion below the first thoracic segment.

The presence of spasticity was determined in the hip adductors, knee flexors and extensors, ankle plantar flexors (gastrocnemius), and elbow flexors and extensors on both sides. Each muscle group was assigned a severity score ranging from 0 (no spasticity) to 3 (1: catch; 2: clonus <5 beats; 3: clonus ⩾5 beats). These scores were summated, giving a sum score ranging from 0 to 36. If spasticity could not be tested, this was indicated as a missing value. Sum scores of spasticity were calculated if 80% of the spasticity test scores were available. They were dichotomized into two groups: (1) no spasticity or catch in only one muscle group (sum score 0 and 1) and (2) more severe spasticity (sum score 2–36).

The use of anti-spasticity medication was registered at each test occasion and was dichotomized in ‘no anti-spasticity medication’ (score: 0) and ‘using anti-spasticity medication’ (score: 1).

Statistics

Individuals with a lesion level above S1, who completed at least two measurement occasions, were included in the analyses. Multilevel regression analyses10 were used to estimate the course of hindrance due to spasticity at t1–t4 and its association with possible determinants. This statistical technique allows meaningful conclusions to be drawn over the entire follow-up period in spite of missing values and varying group composition. Functional hindrance due to spasticity was modelled over time using time periods as categorical variables (dummy), with the time of discharge (t3) as reference – that is, Δt1t3, Δt2t3, Δt3t4. The regression coefficient for a time period describes the change in hindrance due to spasticity over that time period.

Associations between possible determinants and functional hindrance due to spasticity were investigated by adding the determinants separately to the basic model with the time dummies only.

To assess whether one or more determinants had a different course of functional hindrance due to spasticity over time, each determinant (for example, gender) and the interaction between time dummies and the determinant were added separately (one determinant and interactions with time) to the basic time model.

Significant determinants were included in a subsequent multivariate model with a backward selection procedure, stepwise, excluding non-significant determinants (P>0.05), to create the final multivariate model.

The regression coefficients for the time dummies or determinants were converted into odds ratios (ORs): OR=exp(regression coefficient). An OR of 1 indicates that there is no association with this particular determinant, whereas an OR<1 indicates a decreased risk, and an OR>1 indicates an increased risk of hindrance due to spasticity in the presence of the determinant. The corresponding 95% confidence intervals were calculated as: exp (regression coefficient±(standard error × 1.96)).

Results

The characteristics of the participants are described in Table 1.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of all participants who were included that indicated hindrance due to spasticity in all activities together (sum score 2–10) at t1–t4. Figure 2 shows the degree of hindrance due to spasticity during specific activities at t1–t4. Most hindrance due to spasticity was experienced during sleeping and during ‘other activities’. ‘Other activities’ comprised changing position, lying, sitting, standing or walking, catheterization or laxation, sports and driving. Changing position was the most mentioned activity. Some persons mentioned factors like touching, in the morning, stress or infections.

The course of functional hindrance over time is presented in Table 2. Functional hindrance did not change significantly during the study period. Table 3 shows the results of the univariate analysis.

No interaction terms were significant, indicating that there was no difference in change of hindrance over time between determinant groups (for example, men and women).

Table 4 shows the results of the final multivariate model. After the backward selection procedure, only level, spasticity and anti-spasticity medication were found to be significantly independently related to functional hindrance due to spasticity. Individuals with tetraplegia were 2.2 times (1/0.46) more at risk of functional hindrance due to spasticity, those with more severe spasticity were 5.5 times more at risk and those who were using anti-spasticity medication were 4.2 times more at risk.

Discussion

The present study showed that the occurrence of hindrance due to spasticity in all activities together was high in the early phase after SCI. The time between SCI and the start of active rehabilitation (t1) was long (mean 13 weeks). If t1 was defined earlier after SCI the percentage of individuals with functional hindrance due to spasticity at t1 might have been lower. Our study fills the gap in information about hindrance due to spasticity in the early period after SCI. Available studies that describe hindrance due to spasticity include individuals 1 year after SCI and later.3, 5, 7 Spasticity develops during inpatient rehabilitation after the spinal shock period and then decisions have to be made about treatment for spasticity. Adriaansen et al.7 reported problematic hindrance due to spasticity in 34% of individuals 1 year after discharge from rehabilitation in the same study group. Problematic hindrance due to spasticity was registered when an individual scored a lot of hindrance due to spasticity for at least one activity. We found a higher percentage of hindrance 1 year after discharge (55%), because we also included patients with a little bit of hindrance at more than one activity to describe hindrance and not only problematic hindrance.

We also showed the degree of hindrance during specific activities. The percentages of individuals who experienced a lot of hindrance during activities of daily living were relatively low. In other studies3, 5, 6, 7 hindrance due to spasticity in general was measured. Our study gives more detailed information about the occurrence of hindrance due to spasticity in daily living and goals for therapy.

Determinants

Individuals with tetraplegia experienced functional hindrance due to spasticity significantly more often than did those with paraplegia. An explanation can be that individuals with paraplegia show higher levels of functioning and have more compensatory strategies compared with those with tetraplegia.

The OR for having functional hindrance due to spasticity was high for the determinant spasticity. Individuals with more severe spasticity would experience more hindrance due to spasticity. However, this finding is in contrast to the literature,11 which showed that the degree of spasticity is not necessarily related to individual functional complaints. Fleuren et al.12 reported a moderate association between experienced discomfort and perceived degree of spasticity during an activity. The experienced spasticity-related discomfort is influenced by environmental and psychological factors.11, 12, 13

Individuals who used anti-spasticity medication experienced hindrance due to spasticity significantly more often than did those not taking anti-spasticity medication. One can assume that only individuals who experienced a lot of hindrance would have received anti-spasticity medication from their specialist. However, it cannot be inferred from our study whether the medication decreased the hindrance. A review by Taricco et al.14 did not provide evidence for anti-spasticity medication presently used for patients with SCI to decrease spasticity. More research is needed to investigate whether anti-spasticity medication decreases functional hindrance.

Clinical implications

Spasticity can have influence on body functions and structures,15 activities and participation. Our study focused on the influence of spasticity on activities. It is important to focus more on the activities during which patients experience most hindrance due to spasticity and to find out which factors contribute to hindrance. It needs to be investigated in the future how one can influence these factors. If medication or other treatment options are started, functional hindrance due to spasticity needs to be reported before and after the treatment to find out whether the functional hindrance decreases over time. Individuals with tetraplegia and more severe spasticity need specific attention.

Limitations

Only Dutch individuals with an SCI who are aged between 18 and 65 years and had some degree of wheelchair dependency were included. This may influence the degree to which the results can be generalized to the whole population of individuals with an SCI.

Second, functional hindrance due to spasticity was assessed using a subjective rating scale. To improve management of functional hindrance due to spasticity it is important to assess hindrance during various activities also with more objective tools.

Third, in the category ‘other activities’ some individuals mentioned factors instead of specific activities. These factors might have increased the percentages of those who experienced hindrance during activities.

Finally, a cutoff point of hindrance due to spasticity was chosen at ⩾2 because the spasticity sum score was strongly skewed. It was not possible to divide the group of individuals with spasticity into a group with mild and severe spasticity because of the small sample size of the groups.

Conclusion

Functional hindrance due to spasticity occurred in the majority of individuals with SCI and did not change significantly during inpatient rehabilitation and 1 year thereafter. The percentages of individuals who experienced a lot of hindrance due to spasticity during activities of daily living were relatively low. Individuals with tetraplegia and more severe spasticity were at increased risk of functional hindrance due to spasticity.

Data archiving

There were no data to deposit.

References

Pandyan AD, Gegoric M, Barnes MP, Wood D, Van Wijck F, Burridge J et al. Spasticity: clinical perceptions, neurological realities and meaningful measurement. Disabil Rehabil 2005; 27: 2–6.

Maynard FM, Karunas RS, Waring WP 3rd . Epidemiology of spasticity following traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1990; 71: 566–569.

Sköld C, Levi R, Seiger A . Spasticity after traumatic spinal cord injury: nature, severity, and location. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1548–1557.

Adams MM, Hicks AL . Spasticity after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 577–586.

Johnson RL, Gerhart KA, McCray J, Menconi JC, Whiteneck GG . Secondary conditions following spinal cord injury in a population-based sample. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 45–50.

Levi R, Hultling C, Seiger A . The Stockholm Spinal Cord Injury Study: 2. Associations between clinical patient characteristics and post-acute medical problems. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 585–594.

Adriaansen JJ, Post MW, de Groot S, van Asbeck FW, Stolwijk J, Tepper M et al. Secondary health conditions in persons with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal study from 1 year till 5 years post-discharge. J Rehabil Med 2013; 45: 1016–1022.

de Groot S, Dallmeijer AJ, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, Nene AV, Angenot EL et al. Demographics of the Dutch multicenter prospective cohort study ‘Restoration of mobility in spinal cord injury rehabilitation’. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 668–675.

Maynard FM Jr, Bracken MB, Creasey G, Ditunno JF Jr, Donovan WH, Ducker TB et al. International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. American Spinal Injury Association. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 266–274.

Twisk JW . Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis for Epidemiology: A practical Guide. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge. 2003.

Mahoney JS, Engebretson JC, Cook KF, Hart KA, Robinson-Whelen S, Sherwood AM . Spasticity experience domains in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 287–294.

Fleuren JF, Voerman GE, Snoek GJ, Nene AV, Rietman JS, Hermens HJ . Perception of lower limb spasticity in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 396–400.

Voerman GE, Erren-Wolters CV, Fleuren JF, Hermens HJ, Geurts AC . Perceived spasticity in chronic spinal cord injured patients: associations with psychological factors. Disabil Rehabil 2010; 32: 775–780.

Taricco M, Pagliacci MC, Telaro E, Adone R . Pharmacological interventions for spasticity following spinal cord injury: results of a Cochrane systemic review. Eura Medicophys 2006; 42: 5–15.

Diong J, Harvey LA, Kwah LK, Eyles J, Ling MJ, Ben M et al. Incidence and predictors of contracture after spinal cord injury—a prospective cohort study. Spinal Cord 2012; 50: 579–584.

Acknowledgements

The present study is part of the research programme ‘physical strain, work capacity and mechanisms of restoration of mobility in rehabilitation of individuals with a spinal cord injury’. We thank the eight participating rehabilitation centres for their effort and data. This study was supported by the Dutch Health Research and Development Council, Zon-Mw Rehabilitation programme (grant no. 1435.0003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

van Cooten, I., Snoek, G., Nene, A. et al. Functional hindrance due to spasticity in individuals with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation and 1 year thereafter. Spinal Cord 53, 663–667 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.41

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2015.41

This article is cited by

-

The effect of breathing exercises and mindset with or without cold exposure on mental and physical health in persons with a spinal cord injury—a protocol for a three-arm randomised-controlled trial

Spinal Cord (2024)

-

Phenol neurolysis in people with spinal cord injury: a descriptive study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2022)

-

Spasticity Management After Spinal Cord Injury

Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports (2020)

-

A longitudinal study of self-reported spasticity among individuals with chronic spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2018)