Abstract

Study Design:

Cohort.

Objectives:

To examine patterns of pain intensity and variability during acute spinal cord injury (SCI) rehabilitation.

Setting:

Large medical university in the Midwestern United States.

Methods:

Data were collected from the medical records of consecutively admitted patients with new (⩽2 months after onset), traumatic (that is, injury resulting from external forces) or non-traumatic (that is, injury resulting from disease processes) SCI. A total of 11 001 hourly pain ratings on 1709 inpatient days were collected from 56 inpatients. Multi-leveling modeling was used to test models of pain intensity, pain variability, diurnal variability and pain medication administration.

Results:

Pain intensity and variability decreased during the inpatient stay. Compared with those with non-traumatic injuries, those with traumatic injuries had significantly higher pain; those with American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Score (AIS) A scores had a slower decline of pain, while those with AIS D scores had a sharper decline. Pain increased from morning to evening during the latter days of the inpatient stay whereas pain was relatively stable during the early days in the inpatient stay. Those not using a ventilator at admission were significantly less likely to receive a pain medication than those who were, despite no significant differences in pain levels.

Conclusion:

Pain changes during acute rehabilitation, however, the moderating effect of time suggests that change is not consistent across all injury characteristics. Findings suggest that not only should pain management be individualized but it should also reflect a greater understanding of change over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pain after spinal cord injury (SCI) is one of the most prevalent secondary conditions, with estimates ranging from 26 to 95%1 with substantial impact on quality of life.2, 3, 4 Unfortunately, success in treating pain after SCI remains elusive.5, 6 Prospective studies suggest that pain is relatively stable over time and does not necessarily diminish7 and in some cases can increase in the early years postinjury.8 Few studies address pain in the acute period following injury.9 Some work suggests that pain emerges early in the course of recovery and that types of pain vary over time, but that prevalence does not vary by injury level or severity,10 and is sustained into the chronic phase of injury.11 A major criticism of pain research is the common use of retrospective methods and associated problems of recall bias.12, 13 Although recommended as a solution to minimizing bias in pain research,14 few studies in SCI utilize momentary assessments or ‘real time capture’ of pain. Prospective studies often have long lags and use only a handful of assessments to extrapolate pain trajectories. Thus, the purpose of this study was to investigate hourly pain ratings from inpatients with new SCI over the course of acute rehabilitation to examine (1) the pattern of pain intensity (Q1) and variability (Q2); (2) shifts in diurnal patterns of pain intensity across the acute period (Q3); (3) the effects of pain medication administration on pain intensity ratings (Q4); and (4) factors associated with receiving pain medication (Q5).

Materials and methods

Participants

The study sample was drawn from consecutively admitted patients to the acute SCI rehabilitation unit in a major Midwestern US University Hospital. Data were extracted from medical records of patients with new (⩽2 months after onset), traumatic (that is, injury resulting from external forces) or non-traumatic (that is, injury resulting from disease processes) SCI. Age at injury, level and severity of injury, use of ventilator at time of admission, and days from injury to acute rehabilitation admission along with demographic information were recorded. Level of injury was classified by site of injury at C1–C4, C5–C8 or T1–S2 vertebrae. Severity of injury was determined by the AIS15 (A, B, C or D).

Procedures and measures

Hourly pain ratings are taken by nursing staff as standard of care. Ratings are recorded on flow sheets during each of the three nursing shifts (0000 0000 to 0800 hours, 0800 to 1600 hours and 1600 to 0000 hours) on a scale of 0−10, recommended for assessing pain intensity in persons with SCI.16 The administration of pain medication, but not type and dosage, is recorded at the time of pain rating.

Analysis

Multi-level modeling was used to analyze hierarchical data (hourly ratings nested within days and days nested within individuals). Random effects for intercept and slope were used to account for the variability of each participant’s pain rating at baseline (intercept) and the variability of ratings across the inpatient stay within participants (slope). Testing the linear, quadratic and cubic effects of time (for hour and days) indicated a linear effect for both. To test Q1 and Q2, hourly pain ratings were aggregated within each day. For Q3, only ratings between 0800 and 2000 hours were used (70% of data were recorded between these hours). For significant or marginally significant interactions (P<0.07), independent-samples t-tests tested differences in slopes. SPSS 19.0 and SAS 19.0 were used to conduct all statistical analyses.

Statement of ethics

We certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Results

Sample description

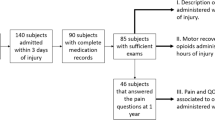

Data were collected from 56 medical charts. Demographic and injury characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Hourly pain ratings

A total of 11 001 hourly pain ratings across 1709 inpatient days (1 through 66 days) were collected. There was a median of 29.5 days per patient and number of pain ratings declined with increasing days. The number of pain ratings taken per hour across the study period varied (Figure 1); in general, they were fewest at the end of nursing shifts (hours 7, 15 and 23) and greatest at the beginning (hours 0, 8 and 16). The time between pain ratings was most commonly 1 h, with 96.3% of ratings taken within 8 h or less of each other (mean hours=3.27, median hours=3.00). The majority of the time when a pain rating was taken, pain medication was not administered (N=9260, 84.2%). A very slight majority of pain ratings were 0, with a mean of 5.05 (±2.2) for non-zero ratings (n=5202).

Pain rating mean (Q1) and variability (Q2)

Pain ratings, on average, decreased during the inpatient stay. Compared with those with non-traumatic injuries, those with traumatic injuries had significantly higher pain; lower age at injury also was significantly associated with lower pain. Those with AIS A scores had a slower decline of pain over time compared with those with AIS D scores who had a sharper decline. Those with T1—S2 had a far slower and more erratic decline over time compared with those with C1—C4 injuries that had a relatively stable decline over time (Table 2). Pain variability also significantly declined across the inpatient stay (Table 3). Compared with those with non-traumatic injuries, those with traumatic injuries had significantly greater pain variability.

Diurnal pattern of pain across inpatient stay (Q3)

There was a significant change in diurnal patterns of pain within day across the inpatient stay (Table 4 and Figure 2). Pain increased from morning to evening during the latter days of the inpatient stay. Conversely, pain was relatively stable across the day early in the inpatient stay. Level of injury was significantly moderated by hour and day such that for those with C1—C4 level injury, the slope of pain within a day started off positive in the first week of the inpatient stay and became increasingly close to zero toward the end. Conversely, for those with C5—C8 injury levels, within-day pain slopes were negative until the very end of the stay, when this group demonstrated a significantly positive slope for pain within a day. Those with T1—S2 injury levels had a somewhat similar pattern of negative within-day slopes for pain early in the inpatient stay, with increasingly positive slopes over the course of the inpatient stay. They had significant positive slopes for both days.

Pain medication administration (Q4 and Q5)

There was no significant association of having pain rating and having received pain medication previously. Time since the previous pain rating was significant such that the longer the time between ratings, the higher the current pain rating (Table 5). A lower pain rating significantly decreased odds of receiving medication. Compared to AIS D, those with AIS A had significantly lower odds of receiving medication and those with AIS C had greater odds. Compared to T1—S2, those with C1—C4 injury levels had significantly lower odds of receiving medication. Those not using a ventilator at admission were also significantly less likely to receive a pain medication than those who were. Hour of day, age at injury and days from injury to rehabilitation also had statistically greater odds; however, the odds ratios were very small (Table 6).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest that pain’s intensity and variability in acute SCI changes over the course of acute rehabilitation, generally declining over time with pain intensity in the moderate range.17 Those with traumatic injuries had significantly greater pain intensity and variability than those with non-traumatic injuries and this relationship did not vary as a function of time. Factors that could contribute to this include the increased incidence of surgery in traumatic patients, the presence of comorbid painful traumatic injuries, and the increased number of neurologically less impaired patients in the non-traumatic group. Gender, age at injury, days from injury to hospitalization and use of a ventilator at admission generally did not have a relationship to pain intensity or variability.

Although there is no consensus on the relationship of injury level or completeness of injury and pain,10 our analysis changed differentially over time. In those with complete injuries (AIS A), pain declined more gradually vs those with motor incomplete injuries (AIS D) who experienced a more precipitous decline. Those with T1—S2 injuries changed more erratically vs those with C1—C4 injuries, who declined in a far more gradual and consistent manner. These results, however, should be interpreted cautiously given a small number of ratings later in the inpatient stay; a further subsampling of these with these injury characteristics reduces power even more. A possible interpretation may be that differences are related to the increased intensity and demand of physical therapy and treatment goals in patients with paraplegia, and their subsequent impact on pain scores at the end of the day throughout rehabilitation. Unlike pain intensity, time did not moderate the effect of any of the covariates on pain variability, suggesting that the relationship of trauma status to pain variability was consistent over time.

The diurnal pattern of pain within days suggested that pain intensity becomes more consistent throughout the day over the course of acute rehabilitation, after sharper increase in pain during the day earlier in the rehabilitation stay. This may reflect the treatment team’s familiarity with the patient and more carefully scheduled medication dosing, the impact of rehabilitation on improving mobility and function with a concomitant decrease in pain with conditioning, improved patient expectation of their ability to function without pain, or a combination of these factors.

Findings related to pain and the administration of pain medication were perhaps most surprising. Despite the absence of an association between pain intensity and ventilator use at admission, those using ventilators had significantly greater odds of receiving a pain medication. Patients with motor function may be repositioned or have their activity modified in response to increased pain. These strategies are less available in patients with high cervical tetraplegia and ventilator dependence and may account for the reliance on pain medication.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are inherent in abstraction of data from the medical record. We were unable to account for the reason for missing data or exert control over the way in which ratings were obtained. We were also unable to determine the pain medication given, as these were not recorded on the nursing flow sheets. Therefore, we are unable to ascertain the impact of scheduled or as needed pain medication on the results. It would be valuable to know whether the decrease in pain we found during the inpatient stay was a reflection of the impact of rehabilitation or an improvement in pain management; knowing the dosage and schedule of morphine equivalent opioids or other prescribed medications is valuable. In addition, the type of pain (for example, neuropathic, musculoskeletal) or its location at each hourly rating also was not available. These data would assist in evaluating the effectiveness of pain management or whether an improvement in pain management could have been anticipated on the basis of medication choices.

Conclusions

Pain intensity changes over time during acute rehabilitation; however, the moderating effect of time for certain injury characteristics suggests that change is not consistent over time. These findings suggest that not only should pain management be individualized but that pain management should be a reflection of our understanding of the differences of patients with different etiologies and neurological level of SCI and profiles over time. Further research could explore whether modifying pain management strategies to reflect the results of this study has an impact on overall pain control. Testing the impact of pain management on functional improvement would give a value for the cost benefits of better pain management.

References

Dijkers M, Bryce T, Zanca J . Prevalence of chronic pain after traumatic spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Res Dev 2009; 46: 13–29.

Widerstrom-Noga E, Biering-Sørensen F, Bryce T, Cardenas DD, Finnerup NB, Jensen MP et al The international spinal cord injury pain basic data set. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 818–823.

Wollaars MM, Post MW, van Asbeck FW, Brand N . Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain 2007; 23: 383–391.

Budh CN, Osteraker AL . Life satisfaction in individuals with a spinal cord injury and pain. Clin Rehabil 2007; 21: 89–96.

Warms CA, Turner JA, Marshall HM, Cardenas DD . Treatments for chronic pain associated with spinal cord injuries: many are tried, few are helpful. Clin J Pain 2002; 18: 154–163.

Heutink M, Post MW, Wollaars MM, van Asbeck FW . Chronic spinal cord injury pain: pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments and treatment effectiveness. Disabil Rehabil 2011; 33: 433–440.

Jensen MP, Hoffman AJ, Cardenas DD . Chronic pain in individuals with spinal cord injury: a survey and longitudinal study. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 704–712.

Kennedy P, Frankel H, Gardner B, Nuseibeh I . Factors associated with acute and chronic pain following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 814–817.

Perry KN, Nicholas MK, Middleton J . Spinal cord injury-related pain in rehabilitation: a cross-sectional study of relationships with cognitions, mood and physical function. Eur J Pain 2009; 13: 511–517.

Siddall PJ, Taylor DA, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ . Pain report and the relationship of pain to physical factors in the first 6 months following spinal cord injury. Pain 1999; 81: 187–197.

Siddall PJ, McClelland JM, Rutkowski SB, Cousins MJ . A longitudinal study of the prevalence and characteristics of pain in the first 5 years following spinal cord injury. Pain 2003; 103: 249–257.

Gendreau M, Hufford MR, Stone AA . Measuring clinical pain in chronic widespread pain: selected methodological issues. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003; 17: 575–592.

Stone AA, Broderick JE, Shiffman SS, Schwartz JE . Understanding recall of weekly pain from a momentary assessment perspective: absolute agreement, between- and within-person consistency, and judged change in weekly pain. Pain 2004; 107: 61–69.

Stone AA, Broderick JE . Real-time data collection for pain: Appraisal and current status. Pain Med 2007; 8: 85–93.

American Spinal Injury Association International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. American Spinal Injury Association, International Spinal Cord Society, Atlanta, GA, 2002.

Bryce TN, Budh CN, Cardenas DD, Dijkers M, Felix ER, Finnerup NB et al Pain after spinal cord injury: an evidenced-based review for clinical practice and research. Report of the national institute on disability and rehabilitation research spinal cord injury measures meeting[mdash]pain committee. J Spinal Cord Med 2007; 30: 421–440.

Forchheimer MB, Richards JS, Chiodo AE, Bryce TN, Dyson-Hudson TA . Cut point determination in the measurement of pain and its relationship to psychosocial and functional measures after traumatic spinal cord injury: a retrospective model spinal cord injury system analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92: 419–424.

Acknowledgements

The contents of this publication were developed under a grant to the University of Michigan Spinal Cord Injury Model System, National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research, Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, US Department of Education (Grant No. H133N060032).

Disclaimer

The contents of this paper do not necessarily represent the policy of the US Department of Education and one should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kalpakjian, C., Khoury, P., Chiodo, A. et al. Patterns of pain across the acute SCI rehabilitation stay: evidence from hourly ratings. Spinal Cord 51, 289–294 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.142

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.142