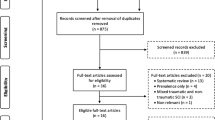

Abstract

This Ludwig Guttmann Lecture was presented at the 2012 meeting of the International Spinal Cord Society in London. It describes the contribution of Stoke Mandeville Hospital to the field of spinal cord injuries. Dr Ludwig Guttmann started the Spinal Unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in 1944 and introduced a novel, comprehensive method of care, which included early admission, prevention and treatment of spinal cord injury related complications, active rehabilitation and social reintegration. Soon a dedicated specialist team was assembled and training of visitors was encouraged, some of whom went on to start their own spinal units. Research went hand in hand with clinical work, and over the years more than 500 scientific contributions from Stoke Mandeville have been published in peer reviewed journals and books. Guttmann introduced sport as a means of physical therapy, which soon lead to organised Stoke Mandeville Games, first national in 1948, then international in 1952 and finally the Paralympic Games in 1960. Stoke Mandeville is regarded as the birthplace of the Paralympic movement, and Guttmann was knighted in 1966. Stoke Mandeville is also the birthplace of the International Medical Society of Paraplegia, later International Spinal Cord Society, which was formed during the International Stoke Mandeville Games in 1961, and of the Society’s medical journal Paraplegia, later Spinal Cord, first published in 1963. Guttmann’s followers have continued his philosophy and, with some new developments and advances, the present day National Spinal Injuries Centre at Stoke Mandeville Hospital provides comprehensive, multidisciplinary acute care, rehabilitation and life-long follow-up for patient with spinal cord injuries of all ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Guttmann Lectures always include some references to Ludwig Guttmann, but this narrative is about Stoke Mandeville Hospital and its contribution to the science and management of spinal cord injuries. I have used my memory, historical sources and references. For a more academic, historical aspect of spinal cord injuries see Silver 2003.1

My personal memories of Ludwig Guttmann are from 1957 when I came to Stoke Mandeville Hospital until his death in 1980. Ludwig Guttmann was autocratic, energetic and industrious, he was immensely talented and a brilliant neurologist. He was a small man but when animated seemed to fill the room. Although he was sometimes harsh with his assistants he had the gift of inspiring great loyalty in his team (Figure 1).

His patients loved and feared him, his staff feared him, but loved him and administrators feared him! If an administrator did not do what he wanted he would say ‘I will take this to a higher authority’ and, if necessary, he did. If he suspected any disloyalty he would say ‘I understand no nonsense’. Translated from Anglo-German this meant ‘I understand what you are up to and I won’t stand for it!’. He won his battles.

Stoke mandeville hospital 1944

Stoke Mandeville Hospital had been built at the beginning of the World War II to be a reserve emergency hospital. It had the facility to admit hundreds of war casualties. By 1944, as there had been no major influx of casualties in the preceding 4 years, much of the hutted hospital had been taken over for other purposes and was, by then, run by the Ministry of Pensions. There were General Medical facilities, a Plastic Surgery Unit, a Rheumatology Research Unit, Pathology, X-Ray Department and operating theatres.

In 1943 the British Government decided to set up several spinal injuries units. At that time servicemen with spinal cord injuries were being treated in military hospitals. They were developing sores and other complications and there was nowhere for them to go. The purpose of military hospitals in the war was to treat the injured and return them to their units so they could fight again. It was impossible to discharge patients with spinal cord injuries and the solution was to start some spinal cord injuries units to ‘care for them’.

Ludwig Guttmann was working in the Research Department in Oxford University where he did not have any clinical role and he was delighted to be asked to lead a spinal unit and he arrived at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in February 1944. All the patients arrived with pressure sores and urinary tract complications. Based on his previous experience, Guttmann knew that pressure sores could be prevented and treated. With the early patients he had to treat the pressure sores, often over many months, before he could even think of rehabilitating the patient. The bladder management of the early patients before arrival at Stoke Mandeville Hospital had usually been with large red rubber supra-pubic catheters, which had only been changed when they finally blocked.

The early patients were all young servicemen, many of them injured by gun shot wounds, but a significant number by road traffic accidents. Once it was established that pressure sores could be treated, the emphasis turned to prevention and it became apparent to Guttmann that it would be far more efficient to admit patients before they developed significant pressure sores and before they had established urinary tract infections. He started the system of early admissions, so that after a few years, when a patient with a new spinal injury was offered to him, he would admit the patient immediately. If the patient had already been injured for some weeks he had to join the waiting list.

Compared with what was happening in general hospitals, Guttmann’s results were spectacularly better and the Spinal Unit grew from a few beds to nearly two-hundred over the next few years. In 1948 a National Health Service was started in the United Kingdom, but Stoke Mandeville Hospital remained under the Ministry of Pensions until it was transferred to the National Health Service in 1953. By that time the Spinal Unit already had the title of the National Spinal Injuries Centre (NSIC), as far as I can tell this was a title bestowed on it by Ludwig Guttmann. He also started to admit civilians and women. A rehabilitation team had evolved and every aspect of their work was strictly controlled by Ludwig Guttmann.

The NSIC remains the National Centre but many more spinal injury centres have opened throughout the United Kingdom.

Dissemination of knowledge and training

In the period of 1944–1961, little of Stoke Mandeville’s work was published in the medical literature. The main exceptions being a chapter that Guttmann wrote in the volume of Surgery in the Medical History of the II World War,2 which was his ‘testament’, but was difficult to access, and a paper on what is now known as autonomic dysreflexia by Guttmann and Whitteridge in Brain.3 This was the first description of raised blood pressure and associated bradycardia that occurs during autonomic dysreflexia.

In spite of the lack of publications from Stoke Mandeville Hospital, the reputation of the hospital was already worldwide in the 1950s, partly because of the fact that Guttmann was a great teacher and experienced in what is now known as public relations. He travelled widely and many doctors visited Stoke Mandeville Hospital and were always well received, even if they came without an appointment. Guttmann would give them a short talk and if there was a ward round taking place they were invited to join the ward round and they were then handed over to Lorie Michaelis, one of Guttmann’s Chief Assistants, who was also very pleased to show them around and teach them all he knew (Figure 2).

Visiting doctors sometimes stayed for long periods and among those who themselves established spinal injury centres, after either prolonged visits or actually being employed at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, were Fred Meinecke, Paul Dollfus, Alain Rossier, David Cheshire, Conal Wilmot, Yutaka Nakamura, Alie Key, Miguel Sarrias, Vincent Forner, Barry Francis-Jones, Federico Montero, Lars Sullivan, Eiji Iwatsubo, Avi Ohry, Amiram Catz and Wagih El-Masry. I particularly remember the visits of Volkmar Paeslack, who came to visit Stoke Mandeville because, as part of his doctoral thesis, he had performed post mortem examinations on patients who died of complications of spinal cord injuries. It was his intention to become a pathologist. He had noted the complications of which the patient died and visited Stoke Mandeville Hospital to confirm his findings. When he saw that at Stoke Mandeville Hospital the patients were surviving and being rehabilitated back into the community, he changed his career plan and spent a long period at Stoke Mandeville and subsequently started the Spinal Unit in Heidelberg.

In those days there was no regulation of visiting doctors and Volkmar joined our team and assisted in research, which led to the first description of multiple cardiac dysrhythmias associated with autonomic dysreflexia during labour in a spinal cord injured woman.4 While Paul Dollfus was working at Stoke Mandeville Hospital as a junior doctor we published the first description of severe bradycardia and cardiac standstill provoked by tracheal suction in tetraplegia.5

Over the years many nurses and doctors were trained, either by being employed in the hospital, by attending courses or by attachments.

Pathology

Tribe6 analysed 150 cases of paraplegia coming to post-mortem at Stoke Mandeville Hospital between 1945 and 1962. Twenty-eight cases died within 2 months of injury. Respiratory failure in cervical lesions and pulmonary embolism in non-cervical lesions were the most important causes of death. One-hundred and twenty-two cases died in the late stages of paraplegia. Renal failure was the major cause of death. There were no cases of pulmonary embolism in these ‘late’ deaths. The renal failure was due to a mixture of three pathologies—chronic pyelonephritis, amyloidosis and hypertension. These all result from the two main complications of paraplegia, namely pressure sores and urinary sepsis. Tribe and Silver7 extended this study to 1965 with particular reference to causes of renal failure.

Pressure sores

From the beginning Guttmann instituted a strict regime of two-hourly manual turning by day and night, at each turn the pressure points were inspected by the nurse in charge of the turning team. As I quoted previously ‘the management of spinal cord injuries is simple, but not easy’. This is particularly so in the prevention of pressure sores. In spite of ordering the two-hourly turns, Guttmann found that patients still developed minor pressure sores and so he appeared in the middle of the night to see what was happening. After two or three dramatic appearances and explanations to the nurses and patients, this problem was overcome. After the period of spinal shock, two-hourly turns were converted to three-hourly turns, but we still had teams of three orderlies and a nurse working on this day and night.

Urinary tract

In the early days all patients arrived with either supra-pubic catheters or indwelling Foley catheters. These had usually only been changed when a catheter blocked. All the patients had severe bladder infections and many had fulminating pyelonephritis and some had periurethral abscesses and fistulae. We had a limited range of antibiotics. The initial management of these infected patients was by regular catheter changes and bladder irrigations. The objective then was to try and remove the catheter leading to either an automatic micturition or an expressible bladder.

As newly injured patients were being admitted, Guttmann tried not to use indwelling catheters at all but instituted a regime of six-hourly, intermittent catheterization. In the beginning this was carried out by a doctor, assisted by a nurse or catheter orderly, using sterile catheters and a non-touch technique.

I personally performed many thousands of catheterizations when I was a junior doctor. The preliminary results of early intermittent catheterization were presented8 and the full analysis published.9 We showed a dramatic decrease in the upper and lower urinary tract complications and the majority of patients were discharged from hospital catheter free, many of them with sterile urine. Our purpose in performing intermittent catheterizations in the early weeks was to tide the patient over the period of spinal shock until an automatic bladder developed, following which the frequency of catheterization was reduced and when the residual urine was <100 ml and if the urine was sterile, catheterization was discontinued. In male patients with complete lesions, some form of external urinal was then used, usually a condom type urinal. The female patients had to rely on regular toileting, which was not very satisfactory.

In 1965 we did not envisage that intermittent catheterization would be a long-term method of bladder management. Subsequently Lapides et al.10 introduced long-term clean, intermittent, self-catheterization, which has revolutionized bladder management in spinal cord injuries and been particularly valuable in women. It is now the most widely used method of bladder management.

Bowel function

Connell et al.11 published a study on the colonic motility following complete lesion of the spinal cord. This demonstrated the differences in resting and reflex activity of the pelvic colon in higher and lower cord lesions.

In recent years there has been much nurse led research into bowel management at Stoke Mandeville Hospital. The centre collaborated on a multicentre, international, prospective, randomized, controlled study of transanal irrigation.12, 13 A study by Coggrave et al.14 examined the management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in the community after spinal cord injury through a national postal survey. Coggrave and Norton15 studied the need for manual evacuation and oral laxatives in a randomised controlled trial of a stepwise protocol, and Coggrave et al.16 described the impact of stoma for bowel management.

Management of the spinal column injury

Quite soon Guttmann formed the opinion that the early operations on the spine, then available (laminectomy, Harrington rods and Meurig-Williams plates), did more harm than good and all patients admitted to the NSIC, Stoke Mandeville Hospital, at that time, were treated non-surgically with postural reduction in bed until the spine was stable. In 1969, as part of a Festschrift for Ludwig Guttmann on his 70th birthday, I published, together with seven senior colleagues, a paper in Paraplegia ‘The Value of Postural Reduction in the Initial Management of Closed Injuries of the Spine with Paraplegia and Tetraplegia’.17 This study looked at outcomes, both from the point of view of the bony injury and the neurological lesion. We were not able to demonstrate any difference in neurological outcome related to the degree of reduction obtained, but there was correlation between the severity of the initial bony lesion and the initial and final neurological outcome. Other aspects of this paper will be discussed under Outcome Measures.

Cardiovascular phenomena

Following on from Guttmann and Witteridge,3 when the raised blood pressure during autonomic dysreflexia was first described, there has been a series of physiological studies from Stoke Mandeville. Some of the key ones were: Johnson et al.18 on orthostatic hypotension and the renin–angiotensin system in Paraplegia, three papers in the Journal of Physiology on cardiovascular reflex response to cutaneous and visceral stimuli in spinal man, cardiovascular changes associated with skeletal muscle spasm in tetraplegic man and cardiovascular responses to tilting in tetraplegic man19, 20, 21 and one in Lancet on the evidence for neurogenic control of cerebral circulation.22

For many years we have had a close collaboration with Chris Mathias and his co-workers, key contributions being ‘Blood pressure plasma catecholomines and prostaglandins during artificial erection in tetraplegic man’,23 ‘Plasma prostaglandin E during neurogenic hypertension in tetraplegic man’,24 ‘Enhanced pressor response to noradrenaline in patients with cervical spinal cord transection’,25 ‘Renin release during head-up tilt occurs independently of sympathetic nervous activity in tetraplegic man’,26 and a chapter in the Handbook of Clinical Neurology ‘The cardiovascular system in tetraplegia and paraplegia’.27

Neurophysiology of spinal cord injury (SCI)

Our long and fruitful collaboration with Imperial College, London, produced numerous studies on neurophysiology of the spinal cord, particularly changes that occur below28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 and above the spinal cord lesions.34, 35 It also introduced the novel technique of transcranial magnetic stimulation, both as a diagnostic tool36 and as a possible therapeutic method in spinal cord injuries.37

Physical rehabilitation

While Guttmann was in charge he dictated and controlled the methods of physical rehabilitation. Some of what Guttmann taught has now been abandoned. For example, he insisted that every patient with a lesion complete from C7 downwards would be taught to stand and ambulate with or without the aid of short or long callipers and elbow crutches. The patients would not be discharged until they were proficient at this. After Guttmann’s retirement a study was performed to see what became of the callipers and it was found that most of them were never used after discharge and the policy was changed to training the patients to stand regularly, usually with a standing frame.

Most of the developments in therapy are published in therapy literature, with which I am unfamiliar, but Stoke Mandeville’s contributions consisted, among others, in a paper by Bergstrom et al.38 about the ability of patients with C6 lesions to transfer, the chapter in the Handbook of Clinical Neurology ‘Physical rehabilitation: principles and outcome’ by Bergstrom and Rose39 and the book ‘Tetraplegia and Paraplegia’ edited by Ida Bromley, first published in 1976, currently on its sixth edition,40 which is also known as ‘the spinal physios’ Bible’.

Spinal cord injuries in childhood

There has been a spinal children’s ward at Stoke Mandeville since the early 1950s and it remains one of the three major centres for spinal cord injuries in children in the world.

Melzak41 published a review of the early childhood cases, followed by Short et al.42 Bergstrom et al.43, 44 described growth, spinal curvature and its management, and the effects of childhood spinal cord injury on skeletal development and late deformity.

Stoke Mandeville has recently opened an additional unit for the treatment of adolescent patients.

Psychology

In Guttmann’s time there was no psychologist in the Spinal Unit. Guttmann said he had been trained in neuro-psychiatry and that he did not need a psychologist and thought they would only cause trouble and unhappiness. Guttmann thought that work was what was needed and, as patients were treated in open 22 or 24 bedded wards, there was much spontaneous group therapy and peer support, and this gave a good outcome in the majority of patients, but in a few it obviously did not. Following Guttmann’s retirement we were impressed by the work of psychologists specializing in spinal cord injury, particularly from the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and in 1988 Paul Kennedy was appointed as Clinical Psychologist to the NSIC (he is now also Professor at Oxford University and continues clinical work and leadership of the Psychology Department at Stoke Mandeville). They have made many contributions to the management of our patients and published prolifically, in studies of depression,45, 46 coping and adjustment.47, 48 Their introduction of Needs Assessment Checklist and Goal Planning has revolutionised our rehabilitation processes.49, 50, 51

Classification and outcome measures

During Guttmann’s time each patient was described as complete or incomplete below the last normal segment and each patient had regular full neurological examinations. Outcome on discharge was described as complete or incomplete, unchanged, improved or worse. In order to improve on this primitive description, when we came to write the paper on the value of postural reduction, I developed a system of classification now known as the Frankel Classification.17 We found that Frankel grades A–E were easy to grade in this retrospective analysis of medical notes. We piloted seven grades, but five was the highest number of grades that could be easily extracted from the notes with a high degree of agreement between the eight authors. The Frankel Classification is a practical combination of an impairment and a disability scale (A and B are impairment grades, C, D and E are disability grades).

The most unexpected finding was the substantial number of cervical cases that were initially complete (Frankel A) that on discharge had progressed to Frankel C (8%) and D (9%) grades (Figure 3).

Neurological outcomes in cervical injuries adapted from Frankel et al.17 In each square of the grid are two letters of the alphabet, the first related to the neurological lesion on admission and the second to the neurological lesion on discharge.

Since then we have contributed to the validation of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord injury52 and development of some new, more precise methods of quantifying the level and density of spinal cord lesions,53 as part of the International Spinal Research Trust (ISRT) funded studies of physiological54, 55, 56 and clinical outcome measures.57, 58, 59, 60

Ageing and survival

Together with the Northwest Regional Spinal Injuries Centre, Southport, UK, and in collaboration with Craig Hospital, Englewood, CO, USA, we have undertaken a longitudinal study on Ageing with SCI in order to provide information on health, functional ability and psychosocial wellbeing in persons with long-term spinal cord injury.61 In 1990, when the study started, all participants had been injured more than 20 years previously. The seventh round of the study is currently underway. So far, the results show that, in spite of a rise in medical and functional problems, reported quality of life and life satisfaction remain relatively good and stable in patients ageing with SCI.62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69

The same collaborators are conducting a parallel study on long-term survival following spinal cord injury.70, 71 The results of the first study show that life expectancy of persons with SCI, though shorter compared with the general population, has improved dramatically over the decades. As people with SCI live longer, the leading causes of death have begun shifting from the typical spinal cord injury related causes to those of the ageing general population. The study update is expected to finish next year.

Sport for the paralysed

After World War II, sport was used in the NSIC as therapy and recreation, however, the young ex-servicemen also wanted to compete. The earlier games were darts, snooker, table tennis, archery and swimming. The first team sport that was tried was wheelchair polo using walking stick, hockey sticks or mallets to hit the ball. This resulted in too many hand and facial injuries and was replaced by wheelchair basketball (Figure 4). The first Stoke Mandeville Games were held in 1948 with 16 competitors. By 1950 there were 14 teams with 60 competitors and in 1952 a team from Holland competed and the Games were designated as International Stoke Mandeville Games. In 1960 the International Stoke Mandeville Games were held in Rome and were retrospectively called the 1st Paralympics. During the Games all the competitors and camp followers were received by Pope John XXIII in the Vatican in a large courtyard and when the Pope came onto the balcony, accompanied by Ludwig Guttmann, a competitor was heard to say: ‘Who is that little man on the balcony with Dr Guttmann?’

In 1964 the Games were held in Tokyo and I went to these Games as team doctor. We were housed in the Olympic Village, which had been vacated by the Olympics a few weeks earlier. The games which were initially only for wheelchairs, over the years were expanded to include many other disabilities. The Paralympics this year will be held in London in the Olympic Park.

Recreational sport has an important part in the rehabilitation and life of many paralysed persons. Only a tiny number take part in elite and Paralympics sport, however, the elite sports, particularly the Paralympics, have played and continue to have a major role in the integration of paralyzed persons into the community. The sight of fit, young people competing in wheelchairs, winning Olympic medals, has changed the public perception of wheelchair users throughout the world. This, together with his concept of managing patients with spinal cord injuries in integrated, dedicated spinal injuries units, remains Sir Ludwig Guttmann’s greatest legacy.

International Medical Society of Paraplegia (later International Spinal Cord Society), Paraplegia (later Spinal Cord)

From the time the International Stoke Mandeville Games started in 1952, the team doctors that accompanied their teams, held the impromptu scientific meeting in the gymnasium at Stoke Mandeville Hospital. In 1961 there was already some formality in these meetings and papers were being presented by most of those attending. The programme was compiled by submitted titles only and nothing was rejected. Ludwig Guttmann chaired every session and the only visual aid was a 2½ × 2½ inch projector powered by an arc lamp. If a slide remained in place for too long, the celluloid started to melt and this helped with the time keeping. The discussions following the presentation were robust and animated. It was really exciting to meet doctors from other countries who were using methods different from ours.

In 1961, during the scientific meeting, Prof. Houssa from Belgium suggested we might form a society. Ludwig Guttmann adopted the suggestion as his own and the International Medical Society of Paraplegia was formed that year (Figure 5). The year 1961 was officially accepted as the first meeting of the Society although the Society was only formed at the end of the meeting. Sir Ludwig Guttmann was the first president for 4 years and the annual scientific meetings of the Society continued to be held at Stoke Mandeville, first in the gym and later in the newly built Floyd Auditorium, except in the Paralympic years, when it was held in the country of the Paralympics. Eventually the Auditorium at Stoke Mandeville, which only seats 130 people, became too small and the last annual meeting of the Society held there was in 1991. Stoke Mandeville Hospital still houses the Headquarters of the International Spinal Cord Society.

The Society decided to publish its own journal Paraplegia and Ludwig Guttmann became the editor. The cost of the journal was included in the member’s annual subscription (initially £5!) and there were four editions per year. In the forward to Number 1, Volume 1, April 1963 Ludwig Guttmann wrote: ‘Up till now the steady increasing amount of published work in the field has been scattered in many journals making a heavy claim on the time of the reader wishing to become familiar with the current literature and new developments. It is to provide an international forum for an easy interchange of ideas by all those responsible for the welfare of our paralysed fellow men, as well as to promote further elucidation of the many and varied aspects of this problem, that this new journal ‘Paraplegia’ is dedicated. Long may it flourish!’72

It did indeed flourish and under the succeeding editorship of Phillip Harris, Lee Illis and now Jean-Jacques Wyndaele, it changed its name from Paraplegia to Spinal Cord to more accurately reflect the contents and increased from four issues per year to the current twelve per year, with current impact factor of 1.805.

The present state of the NSIC, stoke mandeville hospital

The old hutted wards were replaced with purpose built modern facility in 1983 with charitable money raised by Jimmy Savile, who was later knighted for his services (Figure 6). Over the past few decades the NSIC, Stoke Mandeville Hospital has been subjected to financial, organisational and political shocks, but has survived. The basic principles of early admission, care by a dedicated specialist, multidisciplinary team and life-long follow-up have been maintained. Medical and surgical advances and developments in therapy have been adopted. Staff and patient education have been expanded.

The ethos of the Centre is very patient orientated and the previous hierarchal structure has been largely abandoned. The Centre received accreditation from the Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities in 2008 and was re-accredited in 2011. Research continues in all departments and there have been over 500 publications in peer reviewed journals since the foundation of the Centre. A charitable foundation, the Stoke Mandeville Spinal Foundation, has been formed and this year appointed a full time Director of Research.

When I came to the NSIC, Stoke Mandeville in 1957 it was the pre-eminent spinal cord injuries centre in the world. Since then many spinal cord injury centres have developed throughout the world, some of which excel in particular aspects of management or research. However, I believe that Stoke Mandeville remains among the best for all round care. I hope, and believe, that it will go from strength to strength.

Conclusion

Having prepared this narrative I must declare a conflict of interest. I worked at Stoke Mandeville Hospital from 1957 until 2002, when I finally retired from clinical work. I love that place. I owe Ludwig Guttmann a great debt of gratitude, but I was not attracted to spinal cord injury by him. I was attracted and recruited by the patients! I first met them when I was working as a house physician (intern) in the Department of General Medicine in Stoke Mandeville. From time to time our team was asked to see spinal patients for medical problems. I was subsequently invited to a riotous New Year’s Eve Party. I was astonished how active the patients were and the spinal wards were happy communities compared with the wards of general hospitals which, by comparison, were gloomy institutions.

I am privileged to have been allowed to work with patients and their families who overcame tragedy with courage, determination, fighting spirit and above all humour. They have given me friendship and support throughout my career. It was not Ludwig Guttmann that made Stoke Mandeville famous, it was the patients.

References

Silver JR . History of the Treatment of Spinal Injuries. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York. 2003.

Guttmann L . The treatment and rehabilitation of patients with injuries of the spinal cord. In: Cope Z, (ed).. Medical History of the Second World War; Surgery. H.M.S.O: London. 1953 pp 422–516.

Guttmann L, Whitteridge D . Effects of bladder distension on autonomic mechanisms after spinal cord injuries. Brain 1947; 70 (Pt 4): 361–404.

Guttmann L, Frankel HL, Paeslack V . Cardiac irregularities during labour in paraplegic women. Paraplegia 1965; 3: 144–151.

Dollfus P, Frankel HL . Cardiovascular reflexes in tracheostomised tetraplegics. Paraplegia 1965; 2: 228.

Tribe CR . Causes of death in the early and late stages of paraplegia. Paraplegia 1963; 1: 19–47.

Tribe CR, Silver JR . Renal failure in paraplegia. Pittman. Medical Publishing Co. Ltd: London. 1969.

Frankel HL, Guttmann L . Prevention of urinary infection by intermittent catheterisation. Paraplegia 1965; 3: 82.

Guttmann L, Frankel H . The value of intermittent catheterisation in the early management of traumatic paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia 1966; 4: 63–84.

Lapides J, Diokno AC, Silber SJ, Lowe BS . Clean intermittent self-catheterisation in the treatment of urinary tract disease. J Urol 1972; 107: 458–461.

Connell AM, Frankel HL, Guttmann L . Motility of the pelvic colon following complete lesions of the spinal cord. Paraplegia 1963; 1: 98.

Christensen P, Bazzocchi G, Coggrave M, Abel R, Hultling C, Krogh K et al Treatment of fecal incontinence and constipation in patients with spinal cord injury—a prospective, randomized, controlled, multicentre trial of transanal irrigation vs conservative bowel management. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 738–747.

Christensen P, Bazzocchi G, Coggrave M, Abel R, Hulting C, Krogh K et al Outcome of transanal irrigation for bowel dysfunction in patients with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 560–567.

Coggrave M, Norton C, Wilson-Barnett J . Management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction in the community after spinal cord injury: a postal survey in the United Kingdom. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 323–330.

Coggrave M, Norton C . The need for manual evacuation and oral laxatives in the management of neurogenic bowel dysfunction after spinal cord injury: a randomised controlled trial of a stepwise protocol. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 504–510.

Coggrave MJ, Ingram RM, Gardner BP, Norton CS . The impact of stoma for bowel management after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord, e-pub ahead of print 19 June 2012 doi:10.1038/sc.2012.66.

Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, Melzak J, Michaelis LS, Ungar GH et al The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. I. Paraplegia 1969; 7: 179–192.

Johnson RH, Park DM, Frankel HL . Orthostatic hypotension and the renin-angiotensin system in paraplegia. Paraplegia 1971; 9: 146–152.

Corbett JL, Frankel HL, Harris PJ . Cardiovascular reflex responses to cutaneous and visceral stimuli in spinal man. J Physiol 1971; 215: 395–409.

Corbett JL, Frankel HL, Harris PJ . Cardiovascular changes associated with skeletal muscle spasm in tetraplegic man. J Physiol 1971; 215: 381–393.

Corbett JL, Frankel HL, Harris PJ . Cardiovascular responses to tilting in tetraplegic man. J Physiol 1971; 215: 411–431.

Eidelman BH, Debarge O, Corbett JL, Frankel HL . Absence of cerebral vasoconstriction with hyperventilation in tetraplegic man. Evidence for neurogenic control of cerebral circulation. Lancet 1972; 2: 457–460.

Frankel HL, Mathias CJ, Walsh JJ . Blood pressure, plasma catecholamines and prostaglandins during artificial erection in a male tetraplegic. Paraplegia 1973; 12: 205–211.

Mathias CJ, Hillier K, Frankel HL, Spalding JM . Plasma prostaglandin E during neurogenic hypertension in tetraplegic man. Clin Sci Mol Med 1974; 49: 625–628.

Mathias CJ, Frankel HL, Christensen NJ, Spalding JM . Enhanced pressor response to noradrenaline in patients with cervical spinal cord transection. Brain 1975; 99: 757–770.

Mathias CJ, Christensen NJ, Frankel HL, Peart WS . Renin release during head-up tilt occurs independently of sympathetic nervous activity in tetraplegic man. Clin Sci 1980; 59: 251–256.

Mathias CJ, Frankel HL . The cardiovascular system in tetraplegia and paraplegia. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL, (eds).. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 17 (61): ) Frankel HL (co-ed). Spinal Cord Trauma Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, London, New York, Tokyo. 1992 pp 435–456.

Smith HC, Davey NJ, Savic G, Maskill DW, Ellaway PH, Frankel HL . Motor unit discharge characteristics during voluntary contraction in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury. Exp Physiol 1999; 84: 1151–1160.

Smith HC, Davey NJ, Savic G, Maskill DW, Ellaway PH, Jamous MA et al Modulation of single motor unit discharges using magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000; 68: 516–520.

Smith HC, Savic G, Frankel HL, Ellaway PH, Maskill DW, Jamous MA et al Corticospinal function studied over time following incomplete spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 292–300.

Cariga P, Ahmed S, Mathias CJ, Gardner BP . The prevalence and association of neck (coat-hanger) pain and orthostatic (postural) hypotension in human spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 77–82.

Cariga P, Catley M, Mathias CJ, Savic G, Frankel HL, Ellaway PH . Organisation of the sympathetic skin response in spinal cord injury. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002; 72: 356–360.

Cariga P, Catley M, Nowicky AV, Savic G, Ellaway PH, Davey NJ . Segmental recording of cortical motor evoked potentials from thoracic paravertebral myotomes in complete spinal cord injury. Spine 2002; 27: 1438–1443.

Puri BK, Smith HC, Cox IJ, Sargentoni J, Savic G, Maskill DW et al The human motor cortex following incomplete spinal cord injury: an investigation using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 65: 748–754.

Davey NJ, Smith HC, Savic G, Maskill DW, Ellaway PH, Frankel HF . Comparison of input-output patterns in the corticospinal system of normal subjects and incomplete spinal cord injured patients. Exp Brain Res 1999; 127: 382–390.

Davey NJ, Smith HC, Wells E, Maskill DW, Savic G, Ellaway PH et al Responses of thenar muscles to transcranial magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex in patients with incomplete spinal cord injury. J Neurol, Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998; 65: 80–87.

Belci M, Catley M, Husain M, Frankel HL, Davey NJ . Magnetic brain stimulation can improve clinical outcome in incomplete spinal cord injured patients. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 417–419.

Bergström EM, Frankel HL, Galer IA, Haycock EL, Jones PR, Rose LS . Physical ability in relation to anthropometric measurements in persons with complete spinal cord lesion below the sixth cervical segment. Int Rehabil Med 1985; 7: 51–55.

Bergström EMK, Rose LS . Physical rehabilitation: principles and outcome. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL, (eds).. Handbook of Clinical Neurology Vol 17 (61) Frankel HL (co-ed). Spinal Cord Trauma Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, London, New York, Tokyo. 1992.

Bromley I (ed). Tetraplegia and paraplegia: a Guide for Physiotherapists 6th edn. Elsevier Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh. 2006.

Melzak J . Paraplegia among children. Lancet 1969; 2: 45–48.

Short DJ, Frankel HL, Bergstrom EMK . Injuries of the spinal cord in children. In: Vinken PJ, Bruyn GW, Klawans HL, (eds).. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol 17 (61): ) Frankel HL (co-ed). Spinal Cord Trauma Elsevier Science Publishers: Amsterdam, London, New York, Tokyo. 1992.

Bergström EM, Short DJ, Frankel HL, Henderson NJ, Jones PR . The effect of childhood spinal cord injury on skeletal development: a retrospective study. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 838–846.

Bergström EM, Henderson NJ, Short DJ, Frankel HL, Jones PR . The relation of thoracic and lumbar fracture configuration to the development of late deformity in childhood spinal cord injury. Spine 2003; 28: 171–176.

Kennedy P, Rogers B . Anxiety and depression after spinal cord injury: a longitudinal analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 932–937.

Kennedy P, Duff J, Evans M, Beedie A . Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Br J Clin Psychol 2003; 42: 41–52.

Kennedy P, Evans M, Sandhu N . Psychological adjustment to spinal cord injury: the contribution of coping, hope and cognitive appraisals. Psychol Health Med 2009; 14: 17–33.

Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfström ML, Smithson EF . Psychological contributions to functional independence: a longitudinal investigation of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2010; 92: 597–602.

Kennedy P, Hamilton LR . The needs assessment checklist: a clinical approach to measuring outcome. Spinal Cord 1999; 37: 136–139.

Duff J, Evans MJ, Kennedy P . Goal planning: a retrospective audit of rehabilitation process and outcome. Clin Rehabil 2004; 18: 275–286.

Kennedy P, Smithson E, Blakey L . Planning and structuring spinal cord injury rehabilitation: the Needs Assessment Checklist. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2012; 18: 135–137.

Savic G, Bergström EMK, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, Jones PW . Inter-rater reliability of motor and sensory examinations performed according to American Spinal Injury Association standards. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 444–451.

Ellaway PH, Anand P, Bergstrom EM, Catley M, Davey NJ, Frankel HL et al Towards improved clinical and physiological assessments of recovery in spinal cord injury: a clinical initiative. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 325–337.

Kuesgen B, Frankel HL, Anand P . Decreased cutaneous axon-reflex vasodilatation below the lesion in patients with complete spinal cord injury. Somatosens Mot Res 2002; 19: 149–152.

Iles JF, Ali AS, Savic G . Vestibular-evoked muscle responses in patients with spinal cord injury. Brain 2004; 127: 1584–1592.

Ellaway PH, Catley M, Davey NJ, Kuppuswamy A, Strutton P, Frankel HL et al Review of physiological motor outcome measures in spinal cord injury using transcranial magnetic stimulation and spinal reflexes. J Rehabil Res Dev 2007; 44: 69–76.

Savic G, Bergstrom EM, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, Ellaway PH, Davey NJ . Perceptual threshold to cutaneous electrical stimulation in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 560–566.

Savic G, Bergström EMK, Davey NJ, Ellaway PH, Frankel HL, Jamous MA et al Quantitative sensory tests (perceptual thresholds) in patients with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2007; 44: 77–82.

King NK, Savic G, Frankel H, Jamous A, Ellaway P . Reliability of cutaneous electrical perceptual threshold in the assessment of sensory perception in patients with spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2009; 26: 1061–1068.

Savic G, Frankel HL, Jamous MA, King NK, Jones PW . Sensitivity to change of cutaneous electrical perceptual threshold test in longitudinal monitoring of sensory function in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 439–444.

Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Frankel HL, Fraser MH, Gardner BP, Gerhart KA et al Mortality, morbidity, and psychosocial outcomes of persons spinal cord injured more than 20 years ago. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 617–630.

Gerhart KA, Bergstrom E, Charlifue SW, Menter RR, Whiteneck GG . Long-term spinal cord injury: functional changes over time. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993; 74: 1030–1034.

Menter R, Weitzenkamp D, Cooper D, Bingley JD, Charlifue S, Whiteneck G . Bowel management outcomes in individuals with long term spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 608–612.

Weitzenkamp DA, Gerhart KA, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG, Savic G . Spouses of spinal cord injury survivors: the added impact of caregiving. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 822–827.

Savic G, Short DJ, Weitzenkamp D, Charlifue S, Gardner BP . Hospital readmissions in people with chronic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 371–377.

Groah SL, Weitzenkamp D, Sett P, Soni P, Savic G . The relationship between neurological level of injury and symptomatic cardiovascular disease risk in the ageing spinal injured. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 310–317.

McColl MA, Charlifue S, Glass C, Meehan M, Savic G . International differences in aging and spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2002; 40: 128–136.

Drake MJ, Cortina-Borja M, Savic G, Charlifue SW, Gardner BP . A prospective evaluation of urological effects of aging in chronic spinal cord injury by method of bladder management. Neurourol Urodyn 2005; 24: 111–116.

Savic G, Charlifue S, Glass C, Soni BM, Gerhart K, Jamous MA . British ageing with SCI study—changes in physical and psychosocial outcomes over time. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2010; 15: 41–53.

Frankel HL, Coll JR, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG, Gardner BG, Jamous MA et al Long-term survival in spinal cord injury: A fifty year investigation. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 266–274.

Coll JR, Frankel HL, Charlifue SW, Whiteneck GG . Evaluating neurological group homogeneity in assessing the mortality risk for people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 1998; 36: 275–279.

Guttmann L . Foreword. Paraplegia 1963; 1: 1.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dr Gordana Savic and Mrs Marianne Bint for their help in preparing this lecture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Hans L Frankel had worked at Stoke Mandeville Hospital from 1957 until 2002.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frankel, H. The Sir Ludwig Guttmann Lecture 2012: the contribution of Stoke Mandeville Hospital to spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 50, 790–796 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.109

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.109