Abstract

Study design:

Review article.

Objectives:

Critical review of literature on the multiple aspects of sexual rehabilitation in women with spinal cord injury (SCI) from initial recovery to long-term follow-up.

Setting:

Neuro-urology Department.

Methods:

Studies on sexuality selected from PubMed from 1993 to 2009.

Results:

Literature supported by significant statistical analyses reports that females with complete tetraglegia deserved special attention immediately at initial recovery; sexual intercourse is much more difficult for them (as compared with other women with SCI) mainly because of autonomic dysreflexia and urinary incontinence. There are sparse data on predictable factors favoring sexual rehabilitation such as the age SCI was incurred, the importance of one's sexual orientation, and the SCI etiology. Information after initial discharge is based chiefly on questionnaires, which report that as more time passes since the injury, patients attain more sexual satisfaction compared with recently injured women. Studies on neurological changes after SCI, and their effect on sexual response, are supported by a significant statistical analysis, but with few SCI patients. One topic reported the effect of sildenafil on sexuality, without benefit. No paper offers any detailed analysis on the sexual impact of medical and psychological treatments related to SCI. Literature reports that some co-morbidities are more prevalent in women with SCI compared with able-bodied women but data on sexual functioning are missing.

Conclusion:

To improve sexual rehabilitation services, sexual issues and response require evaluation during periodical check-ups using validated questionnaires administered by a physician ‘guide’ who coordinates professional operators thus providing personalized programmable interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) significantly changes motor, sensory, and autonomic function affecting many areas of a person's life, including sexual functioning. Sexuality in women with SCI has largely been neglected.1 One reason may be the male dominance among traumatically injured individuals. Female sexual dysfunction is less problematic than for males with SCI; the majority of para- or tetraplegic women will continue to menstruate, ovulate, and may reproduce.2, 3 The belief that women have a supposedly passive role during intercourse downplays the importance of their sexual dysfunction as well.4

The neurological lesion may determine a varying degree of sexual dysfunction in women with SCI (primary effect). This negative effect on sexual function is often amplified by practical problems caused by a neurological disorder, bladder and bowel management, spasticity, pain, as well as psychological motivations such as low self-esteem and self-image, or lesion-related relationship problems can all influence sexual activity, satisfaction, and sexual response (secondary effect).3, 4

Finally, one's neurologic condition may negatively impact sexual life due to the lack of, or difficulties involved in, interpersonal–social relationships (third effect).1

The rehabilitation of sexual function in females with SCI is aimed at facilitating a form of sexual expression that is both acceptable and satisfying to the women. Sexual satisfaction is not static, though, and holds great subjectivity, and may continue to evolve over time for all individuals. Given this evolution, continued opportunity for sexual counseling is needed even when the women have left the rehabilitation center and returned to their homes and partners. These considerations support the need for services that provide life-long interventions and assessment of these patients through a holistic approach, including a variety of specializations that are relevant to sexual rehabilitation.4

Sexual functioning and the perception of ‘good health’ are strictly correlated. Throughout the last decade, a variety of studies have clarified the association of sexual functioning after SCI with quality of life (QoL).5, 6

Female sexual rehabilitation is recognized as a fundamental component of the overall rehabilitation program; however, retrospective studies identify a gap between services desired by patients and the services actually rendered.7, 8 This study presents a critical review of literature on the multiple aspects of sexual rehabilitation in women with SCI from initial recovery to long-term follow-up.

Materials and methods

Review of sexual rehabilitation commenced at the patients' initial recovery and extended to the short, medium, and long-term follow-ups. According to this criteria of methodology, the results were divided into two parts: initial recovery and follow-ups, identifying subcategories for each. Internationally published studies from the PubMed database with the following key words were used: female SCI sexual function, SCI sexual adjustment, female SCI sexual response, therapies for female SCI sexual dysfunction. Searches were also done using one co-morbidity such as diabetes or cardiovascular, as well as one behavior risk factor (drug/alcohol abuse) together with SCI female or female sexual dysfunction. In the end, key words also comprised the main secondary effects (medical and psychological) related to the SCI condition that may interfere with sexuality such as: urinary incontinence/psychological issues and SCI female sexuality.

Topics of principle significant statistical analysis with at least P<0.05 were selected and reported in this study. The inclusion criteria covered topics dating from 1993 to 2009. Papers concerning experimental models of SCI sexuality and fertility issues were excluded.

Results

Initial recovery

Of the four sections identified, the first and second are based on data gathered, whereas the last two concern possible interventions for facilitating the recovery of sexual activity and an assessment of sexual response post-SCI.

Demographics, detailed medical and sexual histories pre-SCI

Data on female sexuality before SCI are sparse and gathered only through surveys and questionnaires administered many years post-SCI.9 Retrospective reports could exaggerate the effects of injury on sexual functioning. Kreuter et al.10 states, for example, that the high level of sexual desire reported by women pre-SCI compared with able-bodied women may actually be a memory bias or a glorification of life before injury.

Marriage or enduring relationships, and a higher level of instruction, are favorable parameters for better sexual adjustment.11, 12 Conflicting data exist on whether the age SCI was incurred, as well as the importance of one's sexual orientation, is relevant to sexual rehabilitation.2, 13 Ferreiro-Velasco et al.1 found in their study that women under 18 years who suffered an SCI run a higher risk of not having intercourse than those who were over that age when they incurred the SCI (P=0.04).

Topics where statistical analysis reached at least P<0.05 are reported in Table 1.1, 5, 10, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 The large and diverse outcome measures of these studies did not consent a meta-analysis of the data presented.

Etiology of SCI

Literature reports that patients with traumatic SCI achieved greater overall functional improvement compared with non-traumatic SCI.19, 20 In the etiology of non-traumatic SCI, McKinley reported a higher incidence of autonomic dysreflexia (0% versus 24.1%), spasticity (21.1% versus 44.3%), depression (23.7% versus 26.6%), urinary tract infections (52.6% versus 67.1%) and pain (55.3% versus 62.0%) all conditions that interfere with sexual activity and functioning.20

SCI caused by attempted suicide and epileptic episodes present a higher rate of sexual dysfunctions before injury compared with other SCI origins.21, 22, 23 Table 2 shows factors influencing the success of sexual satisfaction and/or sexual adjustment.1, 2, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

Treatment for the secondary effects of SCI interfering with sexual activity and/or response

Medical factors

Pharmacological treatments are mainly used for urge urinary incontinence, muscoloskeletal, and vaginal pain.1, 3, 5 Women with complete tetraplegia are less likely to have sexual intercourse than other women with SCI because they may suffer more frequently from medical factors associated with SCI, such as autonomic dysreflexia, and urinary incontinence (see Table 1).4, 9, 10 Table 3 reports medical problems correlated to SCI.1, 4, 5, 9, 24, 25, 26

Psychological issues

The process of mourning the losses brought on by injury requires psychological support because most women feel their bodies are less attractive after the spinal cord lesion.2 Literature reports that psychological factors may limit sexual activity and/or sexual adjustment more than physical impairments. To optimize their sexual adjustment, it is preferable to involve the patients' partners, thereby fostering trust and a willingness to share personal thoughts and feelings.1, 4 Studies report that peer support for psychological issues affecting women with SCI is extremely positive.10, 27

Monitoring neurological recovery

SCI in women has been shown to affect all aspects of genital neurology, including genital sensation, vaginal lubrication, and orgasm.18, 28 During initial recovery, it is advisable to assess neurological recovery through any change in the ASIA/IMSOP scales of international standards; in fact, the majority of neurological improvement occurs within the first 3 months, but slight improvement can continue up to 18 months or longer.29

Follow-ups after initial discharge

General information

Literature has reported little information on the sexual activity, satisfaction, and response of women with SCI after initial discharge, and has mainly cited a variety of self-reporting surveys done over the internet, telephone, or in person; most of these were women who had spinal cord injuries for >10 years.1, 9, 10 These studies highlighted that most of women did not receive any information on sexuality issues at any time after their injury. Kreuter et al.10 reported that 61% of patients with SCI received no information during their initial recovery, and at the time the survey was administered 40% would have appreciated input on sexuality issues.

Forty to 80% of women continued to be sexually active after injury, but much less so than before injury.1, 9, 10 Ferreiro-Velasco et al. discovered a significant drop in the frequency of intercourse after SCI (with an average of 9.9 times per month before injury compared with 4.2 times after injury. Studies reported that the ability to reach orgasm decreased significantly after injury (see Table 1).1, 18 Literature reports that as more time passes since the injury, patients attain more sexual satisfaction compared with women who have been recently injured.9, 10 They acquire more liberal attitudes toward sex (P<0.02) and engage in more sexual fantasies (P<0.01).30 What is more, the older the injury, the greater the likelihood of a woman with SCI taking part in a sexual relationship (P=0.024).5

Diagnosis and treatments of co-morbidities correlated to sexual function

Literature reports that many co-morbidities are more prevalent in women with SCI compared with able-bodied women; diabetes in these women varies from 15 to 20%, which is three times higher than in the general population.31 Females with SCI present higher risks of cardiovascular disease compared with able-bodied women due to a greater prevalence of lipid disorders, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and obesity.32, 33 Nearly two thirds of individuals with SCI are either overweight or obese34, 35 Literature reports symptoms of major depressive disorders in 7.9–11.4% just 1 year after injury, and women with SCI suffer depression more than their male counterparts15, 36 Thus, over time one or more co-morbidities may be discovered. In truth, studies report that the onset age of SCI represents a significant statistical parameter for alcohol and substance abuse and major depressive symptoms14, 15 (see Table 1). None of these studies on co-morbidities investigated their impact on sexuality issues.14, 15, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 Table 4 presents co-morbidities and harmful lifestyles for female spinal cord injured patients.

Diagnosis and treatments of the primary and secondary effects of SCI on sexual activity and/or response

At present, only one paper reports the effect sildenafil citrate has on sexual response in women with SCI. Results did not indicate significant improvement in vaginal pulse amplitude (P>0.07).38 Studies report SCI-related medical problems that interfere with sexuality including even invasive procedures such as augmentation enterocystoplasty for intractable detrusor overactivity or intrathecal baclofen through an implantable pump for treatment of severe spasticity. However, no paper offered any detailed analysis on their sexual impact.5, 39, 40 Many psychological problems are described: females lacking a partner, having a new partner or first-time sexual experience after SCI, or partner burn-out; again, there is no mention of sexual repercussions.10, 16, 24, 41 Table 5 shows the most common psychological factors interfering with sexual health.1, 4, 5, 10, 16, 27, 41

Neurological monitoring

A modification of neurological status that may influence sexual response can be noted primarily up to 18 months after SCI.28 Studies on sexual arousal, such as Sipski's et al.,17 showed that in 46 SCI patients, arousal significantly increased with both manual and vibratory stimulation. Neurophysiological studies showed that women with the ability to perceive T11–L2 pinprick sensations may have psychogenic genital vasocongestion.42 Sipski et al.18 reported that reflex lubrication and orgasm are more prevalent in women who preserved the sacral reflex arc (S2–S5) Actually, when sensation in the sacral segments is absent, arousal and orgasm may be evoked through43 stimulation of other erogenous zones, suprasegmental to the lesion, such as the breasts, lips, and ears. Komisaruk et al. reported that women with complete SCI at dorsal T10 or above achieved orgasm with vaginal-cervical self-stimulation through the vagus nerves afferent project in the nucleus tractus solitarity region of the medulla oblongata, bypassing the spinal cord. The function magnetic resonance imaging showed activation of the nucleus tractus solitarity and other central nervous systems involved in the orgasm.44

However, sexual satisfaction may occur with or without orgasm. In fact, according to Basson's female sexual response model, if the female sexual experience has been emotionally and physically rewarding, it will enhance the couple's emotional intimacy, thereby increasing the motivation for subsequent sexual psychological satisfaction.45

Discussion

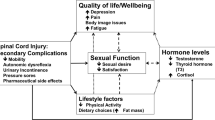

Review of sexual rehabilitation, commencing at the patients' initial recovery and extending to short, medium, and long-term follow-ups, has allowed us to offer some recommendations and identify possibilities in future research (summarized in Figure 1). Studies supported by a significant statistical analysis showed that on average sexual life was impaired by the SCI condition, and only after many years do SCI women attain satisfaction sexually.1, 9, 10 Females with complete tetraplegia deserve special attention immediately during initial recovery because sexual intercourse will be much more problematic due mostly to the possible presence of autonomic dysreflexia and urinary incontinence.4, 9, 10 Moreover, it is important to take into account that some co-morbidities possibly affecting sexual function are related to the onset age of injury such as major depression. At this time, it is not known how much SCI-related depression or alcohol and drug abuse influence sexual activity, response, and satisfaction (compared with a matched control group of SCI women). Therefore, a clinician may need supplementary evaluations and interventions for females with SCI who have these co-morbidities, and may have to rely on professionals working outside of the rehabilitation center or spinal unit. Although studies on neurological changes after SCI, and their effect on sexual response, are supported by a significant statistical analysis, further investigations are needed, with a large number of SCI patients, and a common international standardized study protocol.

Intervening on medical and/or psychological issues associated with lesion-related problems often concomitant in the same female is a well-known part of sexual rehabilitation. Lesion-related problems may influence sexual activity, satisfaction, and response.1, 3, 39, 40 However, beyond diagnosis and treatments of these multiple conditions, the sexual field lacks information in all areas, such as a clear means of evaluating the impact of therapies on sexual response.

This is due, in part, to the dearth of health professionals who have the appropriate sexual health competence and knowledge to support women in SCI-related sexual issues. Although demand is growing for education and training for health care professionals in the area of sexual rehabilitation, unfortunately it is a discipline that is currently non-existent in many rehabilitation centers and countries.46 The complex and multiple aspects of sexual rehabilitation, including its continuing evolution for all individuals, should lead physicians to offer their patients alternative evaluations and treatments. With this in mind, it may be constructive to establish a physician ‘guide’ who can coordinate and activate other operators in the rehabilitation center, or external professional figures to provide personalized programmable interventions for the patients or the couple, including peer support.

Although it is extremely difficult to determine the appropriate timing for follow-ups after initial discharge, a strategy that would make life easier for these women would be to schedule follow-ups that monitor sexual issues to coincide with the women's periodic check-ups (6–12 months) for any SCI-related problems, thus eliminating an extra trip that is arduous for such patients. Moreover, during each follow-up, to assess type and degree of sexual function it would make sense to administer internationally acknowledged questionnaires. The most frequently used questionnaire for female sexual assessment after SCI is the Female Sexual Function Index.47 Objective continuative monitoring is needed in order for any intervention to have an impact on lesion-related problems as well as sexual function. In the meantime, creating a unified scoring system specific to women with SCI is recommended, one that would also address QoL.48 In addition, the effects of aging in females with SCI are only beginning to be studied even though aging has negatively influenced sexual health both physically (genital atrophy, pain, fatigue, symptoms of menopause), and socioeconomically (day-to-day life with disability, financial problems, and separation).49

All countries should invest funds in research directed toward improving QoL, specifically sexual intimacy and pleasure. A comparative investigation of countries showed that generally women with SCI living in Western European countries, Canada, and the United States reported more interest in SCI-related sexual issues, which might be explained by a long tradition of sexual education, an open attitude toward sexual issues, and/or more money invested in SCI research.1, 2 Social factors certainly have an important role and are not contemplated in this study due to their variability. They may contribute to a worsening of self-esteem and a limiting of inter-personal relationships, sexual health, and QoL, considering that many individuals with SCI discontinue working at a younger age.50 Unfortunately, a meta-analysis of the results data was not possible based on the literature available due to the multiple and incomparable variables presented in the studies reviewed.

Finally, notwithstanding all these limitations, we feel this topic is important as a starting point and hope it provides physicians and all operators working in spinal units and rehabilitation centers with tools to better understand the sexual health complexities of women with SCI and to contribute to the improvement of their sexual life.

References

Ferreiro-Velasco ME, Barca-Buyo A, de la Barrera SS, Montoto-Marqués A, Vázquez XM, Rodríguez-Sotillo A . Sexual issues in a sample of women with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 51–55.

Westgren N, Hulting C, Levi R, Sieger A, Westgren M . Sexuality in women with traumatic spinal cord injuries. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1997; 76: 997–983.

Harrison J, Glass CA, Owens RG, Soni BM . Factors associated with sexual functioning in women following spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1995; 33: 687–692.

Forsythe E, Horsewell JE . Sexual rehabilitation of women with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 234–241.

Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL . The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 328–337.

Reitz A, Tobe V, Knapp PA, Schurch B . Impact of spinal cord injury on sexual health and quality of life. Int J Impot Res 2004; 16: 167–174.

McAlonan S . Improving sexual rehabilitation services: the patient's perspective. Am J Occup Ther 1996; 50: 826–834.

Schopp LH, Hirkpatrick HA, Sanford TC, Hagglund KJ, Wongvantunyu S . of comprehensive gynecologic services on health maintenance behaviours among women with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2002; 24: 899–903.

Jackson AB, Wadley V . A multicenter study of women's self reported reproductive health after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Rehabil 1999; 80: 1420–1428.

Kreuter M, Siösteen A, Biering-Sørensen F . Sexuality and sexual life in women with spinal cord injury: a controlled study. J Rehabil Med 2008; 40: 61–69.

Kreuter M, Sullivan M, Siösteen A . Sexual adjustment and quality of relationship in spinal paraplegia: a controlled study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 77: 541–548.

Kreuter M . Spinal cord injury and partner relationships. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 2–6.

Burch A . Health care providers' knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy for working with patients with spinal cord injury who have diverse sexual orientations. Phys Ther 2008; 88: 191–198.

Tate DG, Forchheimer MB, Krause JS, Meade MA, Bombardier CH . Patterns of alcohol and substance use and abuse in persons with spinal cord injury: risk factors and correlates. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1837–1847.

Krause JS, Kemp B, Coker J . Depression after spinal cord injury: relation to gender, ethnicity, aging, and socioeconomic indicators. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81: 1099–1109.

Post MW, Bloemen J, de Witte LP . Burden of support for partners of persons with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 311–319.

Sipski ML, Alexander CJ, Gomez-Marin O, Grossbard M, Rosen R . Effects of vibratory stimulation on sexual response in women with spinal cord injury. J Rehabil Res Dev 2005; 42: 609–616.

Sipski ML, Alexander CJ, Rosen RC . Sexual arousal and orgasm in women: effect of spinal cord injury. Ann Neurol 2001; 49: 35–44.

McKinley WO, Tewksbury MA, Godbout CJ . Comparison of medical complications following non traumatic and traumatic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2002; 25: 88–93.

Yokoyama O, Sakuma F, Itoh R, Sashika H . Paraplegia after aortic aneurysm repair versus traumatic spinal cord injury: functional outcome, complications, and therapy intensity of inpatient rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006; 87: 1189–1194.

Lombardi G, Mondaini N, Iazzetta P, Macchiarella A, Popolo GD . Sexuality in patients with spinal cord injuries due to attempted suicide. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 53–57.

Gutierrez MA, Mushtaq R, Stimmel G . Sexual dysfunction in women with epilepsy: role of antiepileptic drugs and psychotropic medications. Int Rev Neurobiol 2008; 83: 157–167.

Stimmel GL, Gutierezz MA . Pharmacological treatment strategies for sexual dysfunction in patients with epilepsy and depression. CNS Spectr 2006; 11: 31–37.

Ullrich PM, Jensen MP, Loeser JD, Cardenas DD . Pain intensity, pain interference and characteristics of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 451–455.

Baastrup C, Finnerup NB . Pharmacological management of neuropathic pain following spinal cord injury. CNS Drugs 2008; 22: 455–475.

Hammell KW, Miller WC, Forwell SJ, Forman BE, Jacobsen BA . Fatigue and spinal cord injury: a qualitative analysis. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 44–49.

Ekland M, Lawrie B . How a woman's sexual adjustment after sustaining a spinal cord injury impacts sexual health interventions. SCI Nurs 2004; 21: 14–19.

Rees PM, Fowler CJ, Maas CP . Sexual function in men and women with neurological disorders. Lancet 2007; 369: 512–525.

Fawcett JW, Curt A, Steeves JD, Coleman WP, Tuszynski MH, Lammertse D et al. Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as developed by the ICCP panel: spontaneous recovery after spinal cord injury and statistical power needed for therapeutic clinical trials. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 190–205.

Black K, Sipski ML, Strauss SS . Sexual satisfaction and sexual drive in spinal cord injured women. J Spinal Cord Med 1998; 21: 240–244.

Lavela SL, Weaver FM, Goldstein B, Chen K, Miskevics S, Rajan S et al. Diabetes mellitus in individuals with spinal cord injury or disorder. J Spinal Cord Med 2006; 29: 387–395.

Banerjea R, Sambamoorthi U, Weaver F, Maney M, Pogach LM, Findley T . Risk of stroke, heart attack, and diabetes complications among veterans with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 89: 1448–1453.

Bauman WA, Spungen AM . Coronary heart disease in individuals with spinal cord injury: assessment of risk factors. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 466–476.

Chen Y, Henson S, Jackson AB, Richards JS . Obesity intervention in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 82–91.

Rajan S, McNeely MJ, Warms C, Goldstein B . Clinical assessment and management of obesity in individuals with spinal cord injury: a review. J Spinal Cord Med 2008; 31: 361–372 . Review.

Bombardier CH, Richards JS, Krause JS, Tulsky D, Tate DG . Symptoms of major depression in people with spinal cord injury: implications for screening. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1749–1756.

Cheville AL, Kirshblum SC . Thyroid hormone changes in chronic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 1995; 18: 227–232.

Sipski ML, Rosen RC, Alexander CJ, Hamer RM . Sildenafil effects on sexual and cardiovascular responses in women with spinal cord injury. Urology 2000; 55: 812–815.

Chartier-Kastler EJ, Mongiat-Artus P, Bitker MO, Chancellor MB, Richard F, Denys P . results of augmentation cystoplasty in spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord 2000; 38: 490–494.

Plassat R, Perrouin Verbe B, Menei P, Menegalli D, Mathé JF, Richard I . Treatment of spasticity with intrathecal Baclofen administration: long-term follow-up, review of 40 patients. Spinal Cord 2004; 42: 686–693.

Craig A, Tran Y, Middeleton J . Psychological morbidity and spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2009; 47: 108–114.

Sipski ML, Alexander CJ, Rosen RC . Physiologic parameters associated with sexual arousal in women with incomplete spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997; 78: 305–313.

Alexander M, Rosen RC . Spinal cord injuries and orgasm: a review. J Sex Marital Ther 2008; 34: 308–324. Review.

Komisaruk BR, Whipple B, Crawford A, Liu WC, Kalnin A, Mosier K . Brain activation during vaginocervical self-stimulation and orgasm in women with complete spinal cord injury: f MRI evidence of mediation by the vagus nerves. Brain Res 2004; 1024: 77–88.

Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, Derogatis L, Fourcroy J, Fugl-Meyer K et al. Revised definitions of women's sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med 2004; 1: 40–48.

Sharma SC, Singh R, Dogra R, Gupta SS . Assessment of sexual functions after spinal cord injury in Indian patients. Int J Rehabil Res 2006; 29: 17–25.

Rosen RC, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, Shabsigh R et al. The female sexual function index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Marital Ther 2000; 26: 191–208.

Abramson CE, McBride KE, Konnyu KJ, Elliott SL, SCIRE Research Team. Sexual health outcome measures for individuals with a spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2008; 46: 320–324.

Hitzig SL, Tonack M, Campbell KA, McGillivray CF, Boschen KA, Richards K et al. Secondary health complications in an aging Canadian spinal cord injury sample. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2008; 87: 545–555.

Lidal IB, Huynh TK, Biering-Sørensen F . Return to work following spinal cord injury: a review. Disabil Rehabil 2007; 29: 1341–1375.

Acknowledgements

We thank Eugenio Marro for his contribution to this paper. His statistical work on this and other published papers makes him a valuable member of our team.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lombardi, G., Del Popolo, G., Macchiarella, A. et al. Sexual rehabilitation in women with spinal cord injury: a critical review of the literature. Spinal Cord 48, 842–849 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.36

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2010.36

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

The contribution of bio-psycho-social dimensions on sexual satisfaction in people with spinal cord injury and their partners: an explorative study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2022)

-

Metabolic syndrome is the key determinant of impaired vaginal lubrication in women with chronic spinal cord injury

Journal of Endocrinological Investigation (2020)

-

Women’s experiences of sexuality after spinal cord injury: a UK perspective

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

The effect of pelvic floor muscle training and intravaginal electrical stimulation on urinary incontinence in women with incomplete spinal cord injury: an investigator-blinded parallel randomized clinical trial

International Urogynecology Journal (2018)

-

Spinal cord injury and women’s sexual life: case–control study

Spinal Cord (2017)