Abstract

Cooperation and bullying have a subtle yet important interaction that influences the social dynamics in elementary school classrooms. We investigate this interplay in a large sample of 1112 students across 47 public primary classrooms in Chile. Using a video game interface to create a dyadic, non-anonymous social dilemma, we map the cooperative social network within each classroom. In addition, we collect peer nomination data and use the Illinois Bullying Scale to categorize students as bullies, victims, or bully victims. Our results indicate that low levels of received cooperation significantly increase the likelihood of students being identified with the dual role of both bully and victim, known as the bully-victim profile. This negative relationship remains robust even after controlling for demographic and classroom context variables using multilevel regression models and is consistent when employing causal inference techniques such as statistical matching. We propose that the relationship between received cooperation and the bully-victim profile stems from the capacity of received cooperation to capture key factors influencing social relationships among students, such as popularity, prosociality, GPA, and aggressiveness. Our study contributes to the understanding of human interaction in educational settings and it offers a new framework for targeted interventions in primary education, providing insights for future educational policies and practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of social dynamics within structured systems, including classrooms, schools, and other educational settings, is drawing increasing attention (Candia et al. 2022, 2022; Gašević et al. 2013; Halpern, 2005; Kassarnig et al. 2018; Pulgar et al. 2020, 2022). It has been recognized that fostering social relationships within these contexts is paramount for emotional well-being and academic development (Gadermann et al. 2016; Goswami, 2012; Manuel et al. 2021). Simultaneously, these environments host multifaceted dynamics such as aggressive strategies and victimization that sculpt social hierarchies, with effects that permeate age and cultural boundaries (Goodboy et al. 2016; Juvonen and Graham, 2014; Monks et al. 2005; Pronk et al. 2017; Reijntjes et al. 2013; Savahl et al. 2019; Varela et al. 2019). Historical scrutiny of school aggression elucidates the multi-dimensional nature of bullying. This categorization extends beyond victims and perpetrators to include the complex profile of “bully-victims" who endure and perpetrate bullying (Estell et al. 2007; Farmer et al. 2010; Olweus, 1977, 1978, 1993; Schwartz, 2000; Vaillancourt et al. 2003). To address these issues, cooperative learning strategies have been promoted as an effective approach to reduce bullying and improve academic achievement (Thurston et al. 2019; Van Ryzin and Roseth, 2019). However, a significant gap remains to unravel the specific connections between bullying dynamics and cooperative tendencies within educational contexts.

The bully-victim profile is particularly concerning. This profile embodies both the perpetrator and the victim of bullying, which often leads to a cycle of isolation and social neglect (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). This isolation, far from being a mere consequence, deepens the entrenchment in the bully-victim role. Our research focuses on this critical interplay between the bully-victim and victim profiles and the extent to which these profiles embodied behaviors that discourage cooperation.

We hypothesize that reduced peer cooperation is associated with an increased likelihood of being identified as a victim of bullying. This correlation may stem from the decreased social status and stigma attached to victims, perceived as vulnerable and weak. Such perceptions can lead peers to strategically distance themselves to maintain their social standing, exacerbating the isolation of victims not only by their bullies but also by their non-bullying peers, who may also withhold cooperation to protect their own reputations (Juvonen and Galvan, 2008).

In the case of bullies, we posit that the level of peer cooperation they receive could vary significantly. On the one hand, bullies may benefit from enhanced social status due to their dominance and aggressive behaviors (Henrich and Gil-White, 2001), which can sometimes translate into increased peer cooperation. Peers may choose to cooperate with bullies out of a desire for proximity to perceived high-status individuals or out of fear of becoming targets themselves. On the other hand, the same aggressive behaviors that grant them some level of status may also result in social sanctions, leading to less cooperation from peers who view these behaviors unfavorably. This duality suggests that bullies’ experiences of peer cooperation are contingent on a complex balance of fear, admiration, and social rejection (Pellegrini and Long, 2002; Salmivalli, 2010).

In examining the unique and troubling dynamics of bully-victims, we hypothesize that low peer cooperation is associated with an increased likelihood of being identified as a bully-victim, compared to their non-involved counterparts. The ambivalence of this role frequently leads to social isolation, intensified by a self-perpetuating positive feedback loop (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010). Stemming from the compounded stigma of their aggressive behaviors and victim status, this cycle not only solidifies their position as bully-victims but also impedes the receipt of cooperative gestures from peers. Furthermore, since these individuals are both disliked and rejected, they face increased social challenges, further reducing their chances of receiving peer cooperation (Schwartz et al. 2000). This predicament is particularly alarming, as it amalgamates the negative traits of both bullies and victims, leading to a distinct and profound type of social isolation (Hawkley and Cacioppo, 2010), highlighting the urgent need for targeted interventions.

The forthcoming sections will present our experimental approach, explaining the design, data, and methods applied. Our findings will offer a thorough analysis, discussing the implications, limitations, and potential paths for future research and intervention.

Bullying and victimization

Bullying involves repeated aggressive behavior, physical or psychological, aimed at establishing dominance and causing harm. This behavior is recognized as an evolutionary strategy across cultures to enhance status and power at the victim’s expense, influencing their academic and psychological well-being (Chen and Chen, 2020; Goodboy et al. 2016; Olweus, 1978, 1993; Pronk et al. 2017; Reijntjes et al. 2013; Young-Jones et al. 2015). Bullying and victimization dynamics differ by age and maturity, with behaviors intensifying during middle school due to a deeper understanding of social hierarchies (Cillessen and Mayeux, 2004; Monks et al. 2005). Males are often more victimized than females, with distinct patterns of aggression between genders (Felix and McMahon, 2007; Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias, 2015; Nansel et al. 2001). Bullies exhibit low empathy and target perceived weaknesses within peer groups, frequently displaying traits of high extraversion and low agreeableness, which correlates with their engagement in disruptive behaviors (Jolliffe and Farrington, 2006; Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias, 2015; Tani et al. 2003).

Bullying and social implications

Bullies often manipulate social structures to gain popularity, utilizing both coercive and prosocial strategies (Olthof et al. 2011; Perren and Alsaker, 2006; Sutton and Keogh, 2000). Despite their aggressive tactics, bullies can maintain larger social networks than their peers, indicating a complex interplay between aggression and social acceptance (Eslea et al. 2003; Malamut et al. 2020). Classroom environments and teacher interventions play crucial roles in moderating these dynamics, with positive relational settings potentially reducing bullying behaviors and enhancing student relationships (Choi et al. 2011; Kim and Cillessen, 2023).

Cooperation and experimental game theory

This study utilizes experimental game theory to explore cooperative dynamics within classroom settings. Our experimental design, based on the dyadic social dilemma, examines how individual decisions to cooperate reflect broader social interactions and classroom norms (Gelcich et al. 2013; Grueneisen and Tomasello, 2017; Rivera-Hechem et al. 2021; Yamagishi and Cook, 1993). By implementing a game that simulates real-life social dilemmas, we capture the essence of cooperative behaviors among students, providing insights into their social preferences and interactions (Camerer, 2011; Candia et al. 2022, 2022, 2022; Henrich et al. 2005; Pulgar et al. 2020, 2023, 2022; Ramírez et al. 2023).

Methods

Participants sample

This study examines data collected from 47 classrooms across 14 schools within a public school district in central metropolitan Chile, focusing on students in third to fifth grade, with an average age of 9.78 years and a gender distribution of 57% females and 43% males. In addition, student school records were also obtained. In Chile, educational institutions typically host elementary and middle school grades, resulting in most of the sample having been classmates since first grade. Details regarding descriptive statistics are available in the Supplementary material.

In Chile, the School Vulnerability Index (IVE) is a key benchmark for the selection of educational establishments. The IVE, a measure of school-level vulnerability, is frequently employed in educational research in Chile to provide control in econometric models due to its reflection of socioeconomic factors influencing educational environments.

For our study, logistical and cost considerations necessitated a focus on urban schools. We selected an educational district whose IVE closely matched the national urban average to ensure representativeness. Specifically, the district of San Bernardo was chosen because its IVE of 0.72 aligns closely with the national urban mean of 0.73 (standard deviation = 0.11), based on official records from 2017.

Procedure

During the 2017 school year, we conducted data collection by administering a digital game and questionnaires to entire classes simultaneously. We secured active consent from school principals and class teachers, alongside passive consent from parents/guardians, as per our ethical approval protocols. Our fieldwork followed a structured protocol, which is extensively detailed in the Supplementary materials, ensuring the preparation and readiness of the classroom setting, verifying activity schedules, and confirming the availability of necessary equipment.

Protocol summary

-

Preparatory actions: We conducted a thorough verification of the activity schedules and checked all necessary equipment, such as tablets and headphones, to ensure everything was set up for the sessions.

-

Classroom setup: Classrooms were arranged to seat each student separately, creating an optimal environment for students to independently complete the digital questionnaires without interference.

-

Implementation of instruments: The game and questionnaires were delivered on digital tablets. Fieldwork team members closely monitored the process to adhere strictly to the procedural steps.

To address potential biases in self-reporting due to the sensitive nature of bullying behaviors, we implemented specific strategies:

-

Spatial arrangement: We positioned each student separately to maximize privacy and minimize peer visibility of responses, enhancing the reliability of the data collected.

-

Use of headphones: Headphones were employed during the questionnaire sessions to reduce auditory distractions and prevent verbal interaction among students, thereby safeguarding the integrity of their responses.

-

Assurance of anonymity: We emphasized the confidentiality of survey responses, reassuring students that their answers were anonymous and untraceable, which was crucial for eliciting honest responses and reducing reporting biases.

Detailed explanations of these procedures and additional safeguards are available in the supplementary materials (S5), which include a comprehensive description of the experimental protocols designed to maintain the integrity and confidentiality of the collected data.

Instruments and measures

Bullying and victimization score

Illinois Bullying Scale was used to measure bullying and victimization scores from students. Of the three constructs from the original instrument, we only used Bully Score and Victim Score. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Item Reliability were checked (see more details in SM).

Self-reported bully score

The University of Illinois Bully Scale (UIBS; (Espelage and Holt, 2001)) self-report survey was used to assess bullying behavior, which includes teasing, social exclusion, name-calling, and rumor spreading (Espelage et al. 2000, 2003). The survey asked students to indicate the frequency of engagement in each behavior in the past 30 days (e.g., “I teased other students") with response options of “Never", “Almost never", “Sometimes" and “Almost always" that were coded 1 through 4 respectively. The construct validity of this scale has been supported through exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (Espelage and Holt, 2001). In a previous study with a similar population, researchers reported a mean of M = 1.50 and an SD = 0.74 as raw scores (Varela et al. 2020). This study’s reliability level was above the defined Cronbach’s alpha acceptance cutoff (α = 0.828).

Self-reported victimization score

Victimization from peers was assessed using the University of Illinois Victimization Scale (UIVS) (Espelage and Holt, 2001). The survey asked students to indicate the frequency at which certain events have occurred to them in the past 30 days (e.g., “Other students picked on me," and “I got hit and pushed by other students"). Response options were “Never," “Almost never" “Sometimes" and “Almost always". The UIVS was not significantly correlated with the Illinois Bullying scale (r = 0.12), providing evidence of discriminant validity (Espelage et al. 2003). Additionally, this scale has shown to converge with peer nomination data (Espelage et al. 2003). In a previous study with a similar population, a mean score of 1.92 and a standard deviation of 0.99 were reported (Varela et al. 2020). The level of reliability (Cronbach’s alpha) achieved in this study was α = 0.802, which is above our acceptance level.

Dependent variables definition

In our study, we used a combination of self-reported victimization scores (SRVS) and self-reported bullying scores (SRBS) to classify students into four mutually exclusive subtypes of bullying involvement: bully (exclusively SRBS), victim (exclusively SRVS), bully-victim (both SRBS and SRVS), and non-involved (others).

A global standardization procedure (z-score) by gender was applied to the SRBS and SRVS scores of all students. A cutoff of 0.5 standard deviations above the whole sample gender mean was used to identify Bullies and Victims, in accordance with previous research on this topic (Estell et al. 2007; Farmer et al. 2010; Schwartz, 2000; Vaillancourt et al. 2003). Specifically, students were classified as Bully-Victim if they scored 0.5 standard deviations above the gender-standardized mean on both SRBS and SRVS. If they scored above 0.5 standard deviations on SRBS and less than 0.5 standard deviations on SRVS, they were categorized as Bully. If they scored above 0.5 standard deviations on SRVS and less than 0.5 standard deviations on SRBS, they were classified as Victim, and if they scored less than 0.5 standard deviations on both scores, they were classified as Non-Involved.

Standardization by gender was used because females typically have lower average scores than males in both bullying and victimization scores. This helped to balance the categories across gender. In this sample, the mean SRBS score for males was 1.90 and for females was 1.55, with a significant difference (0.35, t = 10.06) between the means. Similarly, for SRVS, the mean for males was 2.49, and for females 2.28, with a significant difference (0.21, t = 3.89) between the means. For more details, please see the Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Item Reliability on SRBS and SRVS section in the supplementary material.

Game mechanics

This experiment situates students in paired scenarios with all their classmates across distinct rounds. Each round maintains an onymous (or non-anonymous) frame, thereby conducting a total of n−1 rounds for a class comprised of n students. Within each round, players simultaneously adopt the dual roles of the “Allocator" and the “Receiver."

Assuming the role of the Allocator, every player starts each round with an endowment of ten tokens (Fig. 1.1), and they face the decision of how many tokens, if any, to send to their paired Receiver. Each token sent by the Allocator is doubled upon receipt (Fig. 1.2). As such, the total number of tokens a student amasses in a round is determined by the tokens they retained as an Allocator, supplemented by double the number of tokens dispatched by the other player (Fig. 1.3).

The game is structured such that full cooperation–both players exchanging all their tokens–yields the maximum cumulative number of tokens for the pair, with each student accumulating 20 tokens. However, the game design also incentivizes non-cooperation. A student can maximize their individual gain by choosing to keep all their tokens (retaining 10 tokens) while simultaneously receiving the full allocation from the other player (yielding an additional 20 tokens). This dynamic reflects the core tension inherent in social dilemmas, striking a delicate balance between collective benefits and individualistic gain.

Cooperation mapping and measures

In order to map a cooperation network for each classroom, we utilized the game described in the previous section. In each dyadic interaction, the tokens sent from student i to student j are represented by a directed edge from i to j, with the weight of the edge equal to the number of tokens sent (see). Then, we constructed the individual-level topological measures from the elicited networks described in Table 1. In order to have comparable quantities between classrooms with a different number of classmates, we divided each quantity by n−1 where n is the number of students in that class that played the game. Therefore, values for every student can only take values between 0 and 1.

Peer nominated variables

This survey facilitated the construction of variables that reflect perceptions among peers, which include:

-

Popularity: calculated as the difference between nominations for being the most popular and not popular.

-

Aggressiveness: sum of nominations for tendencies to start fights and laugh at others.

-

Prosociality: aggregate of nominations indicating kindness and cooperativeness. Social preference: difference between nominations for most liked and least liked by their peers.

-

Friendshipness: total number of nominations as best friends.

These variables were introduced to control for individual differences in social standing and behavior, which could potentially influence the outcomes observed in our game-based measures as well as their correlation with self-reported measures of bullying and victimization. A detailed description of the survey methodology and the process for constructing these variables is provided in the supplemental materials section S6.

Multilevel models

The inherent nested structure of educational data—where individual observations are grouped within larger units such as classrooms or schools—requires a specialized approach to analysis. Multilevel models are particularly suited for this purpose, as they account for dependencies within the data by allowing for variance at both individual and group levels. This is crucial, especially when compared to traditional fixed-effects regression models, which do not accommodate variance across higher organizational levels.

In our study, the behavior of students in the gaming scenarios is assessed within the context of their respective classrooms. Since cooperative behaviors are interdependent and vary between classrooms, multilevel modeling is particularly well-suited. This approach not only manages the hierarchical structure of the data but also effectively controls for influences at the classroom level, such as bullying and victimization dynamics, as well as other contextual effects. This robust framework ensures that our analyses accurately reflect the complex interplay of individual and collective factors in educational settings.

To ensure the meaningful comparison of our results, all independent variables were standardized employing grand mean centering (Gelman, 2008), a standard practice in multilevel modeling. This method facilitates a consistent basis of measurement across the diverse variables, fostering a coherent interpretation of findings.

Results and discussion

Our exploration of cooperation within classrooms reveals a complex network of interactions.

We started by examining the distribution of allocated tokens during gameplay, employing a weighted histogram methodology (Fig. 2a). Each classroom varies in the total number of rounds, due to the relationship (n−1), where n is the total number of participating students. This approach is instrumental. Typically, students allocate all 10 tokens or none, each option occurring with ~25% frequency. Further analysis using a two-dimensional histogram of the minimum and maximum allocated tokens (Fig. 2b) shows that ~50% of students exhibit a wide range of behavior, giving zero tokens to at least one peer and ten to another.

a We dive into the realm of individual strategies, visualized through a histogram of sent tokens. The majority of students appear to play the extremes, either fully leveraging their endowment of ten tokens or sending just a fraction of it, reflecting intriguing behavioral tendencies. b Further dissection of the token distribution is carried out through a histogram highlighting the minimum and maximum contributions by each student. The distribution unveils a propensity among the majority of students to explore the entire spectrum of possible token contributions, indicating that the choice of sending strategies is entwined with the relational dynamics with their peers. c The macro-level manifestation of individual strategies is assembled into a comprehensive dyadic-level histogram, providing a bird’s eye view of the experiment. Three key interaction patterns emerge—scenarios where both players send a few tokens (bottom-left), instances where both players fully utilize their endowment (top right), and situations characterized by an imbalance with one player sending most of the tokens while the other sends few (bottom right).

A heatmap of dyadic outcomes (Fig. 2c) highlights varying levels of cooperation, conflict, and asymmetry. Darker shades represent higher frequencies, while lighter shades indicate lower frequencies. We observe three distinct clusters: dyads with strong mutual cooperation (e.g., 10–10 dyads), dyads with minimal mutual cooperation (e.g., 0–0, 1–1, 1–0, 0–1, and even 0-2, 1–2, 2-2), and dyads marked by high asymmetry (e.g., 10–0, 10–1, 10–2). This distribution challenges game theory’s prediction of equilibrium at zero sent tokens for both players, assuming rational preferences and individual payoff maximization. Despite the significant presence of 0-0 dyads (~4.5%), they comprise just half of the mutually cooperative dyads (9.18%).

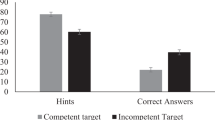

Next, we focus on bullying interactions. Our findings (3A) spotlight the variance of “in-strength" across different categories. Strikingly, bully-victims, those students caught in the crossfire as both perpetrators and victims, manifest the lowest in-strength. This evidence sheds light on the correlation between received tokens in a social dilemma task and the likelihood of being classified as a bully, victim, or bully-victim in the classroom. To handle the nested structure of our data, we employed multilevel logistic models with random intercepts for classrooms, taking into account potential confounding variables such as students’ socio-behavioral characteristics, gender, GPA, and attendance at individual and classroom levels.

In our effort to elucidate the dynamics among bully-victims, victims, and bullies, our models reveal significant insights. Bully-victims (3B), victims (3C), and bullies (3D) each show unique correlations with in-strength, an essential predictor for identifying students in these categories. A striking tenfold decrease in the probability of being a bully-victim is observed when moving from minimum to maximum in-strength. While a less dramatic but still significant effect is seen for victims, no predictive power of in-strength is noted for bullies.

An in-depth comparison between bully-victims and non-involved students, as shown in Fig. 3E, unveils significant insights into the dynamics of bullying behavior. Specifically, there is a marked negative association between the in-strength (a measure of incoming connections) and the likelihood of being classified as a bully-victim. A change of one standard deviation in in-strength corresponds to a decrease in the odds of being classified as a bully-victim by 38% (Odds ratio = exp(−0.47) = 0.62).

A The variation of in-strength among different bullying interaction categories is depicted, with Bully-Victims demonstrating the lowest in-strength. Subsequently, in-strength is utilized to predict bully-victims (B), victims (C), and bullies (D). The analysis reveals a stronger explicative effect for bully-victims, significant for victims, and insignificant for bullies. Error bars indicate the standard error of the mean, and shaded regions represent the 95% confidence intervals. E Regression results for the bully-victim category using a one-vs-all multilevel classification.

Furthermore, the data indicates that increasing aggressiveness and having a higher number of friends are factors that substantially raise the probability of being identified as a bully-victim. Interestingly, these effects are more pronounced in the bully-victim category than in other classifications related to bullying.

There is a significant negative impact on both prosociality and grade point average (GPA) for bully victims, suggesting a broader pattern of perceived prosociality and underachievement. This observation underscores the complex nature of the bully-victim profile and the multifaceted challenges they face, not only in social relationships but also in their academic performance.

When contrasting victims with non-involved peers (Figure S7), the in-strength is negatively correlated with the probability of being classified as a victim. A significant positive correlation between an increased number of friends (friendshipness) and the likelihood of being classified as a victim is also observed, highlighting the complex dynamics within this group.

Lastly, our models reveal a negative correlation between GPA and social preference scores with the probability of being identified as a bully (Figure S8). In contrast, we find a positive correlation between aggressiveness and the likelihood of being classified as a bully. Remarkably, the network variable in-strength or any other game metric has no significant effect on bullying behavior.

This mosaic of findings underscores the correlation between the average tokens received by students in the game and the likelihood of self-reporting victimization. These correlations, consistent across different models, suggest that the classroom’s disposition towards cooperative relations could be a significant indicator of possible behaviors and self-perceptions related to bullying.

The findings present a compelling narrative. Both victims and bully victims are less likely to receive tokens, suggesting diminished social connectivity. Conversely, bullies, despite their aggressive behavior, maintain larger friendship groups (Figure S8), a seemingly paradoxical phenomenon.

Our results show that receiving fewer tokens correlates strongly with being a bully-victim or a victim. Such findings suggest that bullying involvement and the extent to which a student is cooperative or deemed worthy of cooperation by classmates in a social dilemma task are tightly interwoven. This reinforces the idea that the classroom’s dynamics and distribution of social resources could provide valuable insight into understanding the social processes leading to victimization and dual-role bullying.

Now we ask what in-strength measure is capturing in the social dynamic of school coexistence? We note that the in-strength measure serves as a key to the multi-dimensional map of student attributes in Fig. 4. It presents a compelling matrix of relationships that echoes the social and academic universe within the classroom. The in-strength measure showcases intriguing correlations with popularity (Fig. 4A), prosociality (Fig. 4B), friend networks (Fig. 4C), and social preferences (Fig. 4D), all climbing up with a positive slope. The more tokens a student receives, the higher their standing in these domains, indicating a greater degree of acceptance, empathy, and friendship ties, alongside a propensity to favor the group’s welfare over individual gain. These correlations, although diverse, share the common thread of peer recognition, translating into higher in-strength values.

The in-strength measure acts as a multi-dimensional lens to student characteristics, spanning A popularity, B prosociality, C friend networks, D social preferences, E academic performance (GPA), F attendance, G aggressiveness, H physical aggression, and I relational aggression. These attributes are predominantly identified through peer nominations, save for academic performance and attendance, which are procured from official school records. Black dots symbolize the average, with error bars encapsulating the standard error of this average and a confidence band of 95%. It is noteworthy to mention that all variables are evaluated in terms of class z scores.

Parallel to this, a positive correlation of in-strength with academic performance (Fig. 4E) and attendance (Fig. 4F), both drawn from the school’s official records, reveals an interesting facet of the classroom dynamics. Students who attend school more frequently or maintain a higher GPA tend to receive more tokens, further cementing their social status.

On the other end of the spectrum, the in-strength measure unveils a stark negative correlation with aggressiveness (Fig. 4G), physical aggression (Fig. 4H), and relational aggression (Fig. 4I). As these values increase, the in-strength measure dips, unmasking an inverse relationship. It underscores that students exhibiting aggressive behavior, whether physical or relational, tend to receive fewer tokens, indicating their marginalization within the classroom network.

Each black dot in the figure acts as a beacon, illuminating the average correlation, while the accompanying error bars and the 95% confidence band provide a boundary, charting the variance and the reliability of these relationships. All these variables are z-scored, offering a standardization that allows for comparing students across classes. As depicted by the in-strength measure, this intricate network of relationships crystallizes the complex interplay of the social and academic fabric within the classroom, underlining its potential to predict bullying behaviors.

In our investigation, we focused on the “out-strength" metric (Fig. S9), a measure commonly used in network science. However, our observations led us to intriguing findings. While the “out-strength" demonstrated a moderate correlation with “in-strength" (measured at 0.272), it fell short of capturing the multifaceted characteristics of the students. In this context, we further explored the role of out-strength in our analysis of non-cooperative behavior and victimization among students (Fig. S10). To test the validity of an alternative explanation–that out-strength might influence perceived victimization–we controlled for out-strength in our regression model. The results indicate that including out-strength in the analysis does not alter the main findings, effectively ruling out this alternative explanation. Thus, the link between non-cooperative behavior and victimization appears to be robust, independent of the out-strength variable.

The “in-strength" (Fig. 4), in contrast, shows a remarkable sensitivity to the intricate web of social and academic interactions among elementary school children. This duality hints at the complexity of student networks, calling for a careful interpretation of these network measures in capturing the rich fabric of children’s interactions. This contrast also points towards the divergent validity of “in-strength" to capture students’ features. Furthermore, the influence of ’in-strength’ on Bully-Victims remains consistently strong across various quantile thresholds (0.65, 0.75, and 0.85). Notably, the observed effect intensifies as the threshold increases, underscoring the robustness of these results. For a detailed visualization, refer to Figure S11 in the Supplementary Material.

Finally, we expect that received cooperation will serve as a red flag for the isolated profile of bully victims. Recognizing and responding to their reduced received cooperation is imperative, as it paves the way for timely intervention, thereby addressing a critical aspect of their social plight.

Conclusions

In the intricate web of human interactions, the classroom serves as a representative model, mirroring the complexity of the broader social network and exerting a significant long-term impact. Our exploration into this micro-world unravels the distinctive cooperative relationships that characterize bullies, victims, and the dual role of bully victims. Through the lens of multilevel models, our findings illuminate subtle differences in cooperative dispositions, where victims and bully victims are less likely to receive cooperation from their peers. A picture emerges, robust against the background noise of demographics and context, where cooperation takes on a nuanced form.

Yet, bullies’ reciprocation of cooperation seemed to be more independent of received and sent cooperation. Our results deepen our understanding of bullying dynamics by revealing the significant impact that individual and relational factors within the classroom have on creating a bullying-prone environment. They provide a pathway to developing classrooms that are less vulnerable to bullying. Our study emphasizes a crucial point: to effectively address bullying, we must understand and enhance the dynamics of cooperation within the classroom.

Like all scientific inquiries, our work must be tempered by awareness of its limitations. The single set of nominations per school year does not capture potential changes in social dynamics over time. The focus on a single country may limit the generalizability of our findings, highlighting the need for further cross-cultural exploration. Additionally, a more profound analysis could be undertaken by considering the roles of gender, race, and socio-economic factors in the complex dynamics of bullying behavior.

Nevertheless, our findings provide a significant contribution to the understanding of the relationship between cooperation and bullying. We have expanded beyond examining these phenomena in isolation and have identified them as interrelated elements within the classroom’s social structure. By utilizing a game-based approach, we have provided new insights into this relationship, suggesting that these findings could be used to predict and potentially reduce bullying in schools.

Looking forward, there is potential to explore interventions that could leverage the power of cooperation to improve classroom dynamics. As we continue on this path, we are driven by the belief that understanding these connections could lead to a classroom environment that fosters not only learning but also harmony and unity. The complexity of this challenge is not a deterrent; rather, it presents an opportunity to create meaningful change and transformation.

Limitations

Despite employing several strategies to reduce bias in self-reporting of bullying behaviors, such as ensuring confidentiality and minimizing peer influence through classroom arrangements and the use of headphones, inherent limitations persist. The classroom environment may still influence how students report sensitive issues like bullying or victimization, potentially leading to underreporting or overreporting. These factors must be acknowledged when interpreting the findings. Future research should consider integrating observational techniques or teacher reports to cross-validate self-reported data, highlighting the need for methodological advancements to more accurately depict bullying dynamics.

Our research was conducted in a district with an IVE of 0.72, closely aligning with the national urban average of 0.73, suggesting that our observations might be applicable to urban environments with similar vulnerability levels. However, schools with notably higher or lower IVEs may experience different bullying and peer cooperation dynamics. To broaden the understanding of how diverse socioeconomic contexts affect student behavior and peer interactions, future studies should investigate these variables across a wider range of settings.

The study’s insights into bullying and peer cooperation are drawn from middle-income urban schools, and generalizing these findings to schools with significantly different vulnerability indexes (IVE) demands caution. Aggression and victimization are affected by various factors, including economic and cultural capital. Research indicates that students from wealthier backgrounds tend to encounter fewer aggressive behaviors (Hosozawa et al. 2021; Tippett and Wolke, 2014).

Data availability

Our current study is part of a larger, ongoing research project. The data used in this study are intricately linked to two other studies we are developing for future publications. The premature release of this data could compromise the integrity and novelty of our forthcoming work. We plan to release the data with these other publication during 2025. Please contact the corresponding author for more details.

References

Camerer C (2011) The promise and success of lab-field generalizability in experimental economics: a critical reply to levitt and list. (Available at SSRN 1977749)

Candia C, Maldonado-Trapp A, Lobos K, Peña F & Bruna C (2022) Disadvantaged students increase their academic performance through collective intelligence exposure in emergency remote learning due to covid 19. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.05621

Candia C, Oyarzún M, Landaeta V, Yaikin T, Monge C, Hidalgo C, Rodriguez-Sickert C (2022) Reciprocity heightens academic performance in elementary school students. Heliyon 8:e11916

Candia C, Pulgar J & Pinheiro F (2022) Interconnectedness in education systems. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2203.05624

Chen L, Chen X (2020) Affiliation with depressive peer groups and social and school adjustment in chinese adolescents. Dev Psychopathol 32:1087–1095

Choi J, Johnson DW, Johnson R (2011) Relationships among cooperative learning experiences, social interdependence, children’s aggression, victimization, and prosocial behaviors. J Appl Soc Psychol 41:976–1003

Cillessen AH, Mayeux L (2004) From censure to reinforcement: developmental changes in the association between aggression and social status. Child Dev 75:147–163

Eslea M, Menesini E, Morita Y, O’Moore M, Mora-Merchán J, Pereira B, Smith P (2003) Friendship and loneliness among bullies and victims: data from seven countries. Aggress Behav 30:71–83

Espelage D, Bosworth K, Simon T (2000) Examining the social context of bullying behaviors in early adolescence. J Couns Dev 78:326–333

Espelage D, Holt M (2001) Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: peer influences and psychosocial correlates. J Emotional Abus 2:123–142

Espelage D, Holt M, Henkel R (2003) Examination of peer-group contextual effects on aggression during early adolescence. Child Dev 74:205–220

Estell D, Farmer T, Cairns B (2007) Bullies and victims in rural african american youth: behavioral characteristics and social network placement. Aggress Behav 33:145–159

Farmer TW, Petrin RA, Robertson DL, Fraser MW, Hall CM, Day SH, Dadisman K (2010) Peer relations of bullies, bully-victims, and victims: the two social worlds of bullying in second-grade classrooms. Elem Sch J 110:364–392

Felix E, McMahon S (2007) The role of gender in peer victimization among youth: a study of incidence, interrelations, and social cognitive correlates. J Sch Violence 6:27–44

Gadermann AM, Guhn M, Schonert-Reichl KA, Hymel S, Thomson K, Hertzman C (2016) A population-based study of children’s well-being and health: The relative importance of social relationships, health-related activities, and income. J Happiness Stud 17:1847–1872

Gašević D, Zouaq A, Janzen R (2013) Choose your classmates, your GPA is at stake!: the association of cross-class social ties and academic performance. Am Behav Sci https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764213479362

Gelcich S, Guzman R, Rodríguez-Sickert C, Castilla JC, Cárdenas JC (2013) Exploring external validity of common pool resource experiments: insights from artisanal benthic fisheries in chile. Ecol Soc 18:228–244

Gelman A (2008) Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Stat Med 27:2865–2873

Goodboy AK, Martin MM, Rittenour CE (2016) Bullying as a display of social dominance orientation. Commun Res Rep. 33:159–165

Goswami H (2012) Social relationships and children’s subjective well-being. Soc Indic Res 107:575–588

Grueneisen S, Tomasello M (2017) Children coordinate in a recurrent social dilemma by taking turns and along dominance asymmetries. Dev Psychol 53:265

Halpern D (2005). Social capital. Polity, Social Science

Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT (2010) Loneliness matters: a theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Ann Behav Med 40:218–227

Henrich J, Boyd R, Bowles S, Camerer C, Fehr E, Gintis H, Tracer D (2005) Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behav Brain Sci 28:795–815

Henrich J, Gil-White FJ (2001) The evolution of prestige: freely conferred deference as a mechanism for enhancing the benefits of cultural transmission. Evol Hum Behav 22:165–196

Hosozawa M, Bann D, Fink E, Elsden E, Baba S, Iso H & Patalay P (2021) Bullying victimisation in adolescence: prevalence and inequalities by gender, socioeconomic status and academic performance across 71 countries. EClinicalMedicine 41:101142

Jolliffe D, Farrington D (2006) Examining the relationship between low empathy and bullying. Aggress Behav 32:540–550

Juvonen J and Galvan A (2008) Peer influence in involuntary social groups. In: Understanding peer influence in children and adolescents, 225–244

Juvonen J, Graham S (2014) Bullying in schools: the power of bullies and the plight of victims. Annu Rev Psychol 65:159–185

Kassarnig V, Mones E, Bjerre-Nielsen A, Sapiezynski P, Dreyer Lassen D, Lehmann S (2018) Academic performance and behavioral patterns. EPJ Data Sci 7:10

Kim J, Cillessen AHN (2023) Prospective associations of prosocial behavior and aggression with social preference: Moderation by classroom levels of peer-perceived liking and disliking by the teacher. Int J Behav Dev 47:423–432

Malamut S, van der Berg Y, Lansu T, Cillissen A (2020) Dyadic nominations of bullying: comparing types of bullies and their victims. Aggress Behav 46:232–243

Manuel D, Adams S, Mpilo M, Savahl S (2021) Prevalence of bullying victimisation among primary school children in south africa: a population-based study. BMC Res notes 14:1–6

Mitsopoulou E, Giovazolias T (2015) Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: a meta-analytic approach. Aggress Violent Behav 21:61–72

Monks CP, Smith PK, Swettenham J (2005) sychological correlates of peer victimisation in preschool: social cognitive skills, executive function and attachment profiles. Aggress Behav 31:571–588

Nansel T, Overpeck M, Pilla R, Ruan W, Simons-Morton B, Scheidt P (2001) Bullying behavior among u.s. youth: prevalence and association with psychosocial adjustment. J Am Med Assoc 285:2094–2100

Olthof T, Goossens FA, Vermande MM, Aleva EA, van der Meulen M (2011) Bullying as strategic behavior: relations with desired and acquired dominance in the peer group. J Sch Psychol 49:339–359

Olweus D (1977) Aggression and peer acceptance in adolescent boys: two short-term longitudinal studies of ratings. Child Dev 48:1301–1313

Olweus D (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. In: Hemisphere

Olweus D (1993) Bullying: what we know and what we can do. In: Mental disorder and crime, 353–365

Pellegrini AD, Long JD (2002) A longitudinal study of bullying, dominance, and victimization during the transition from primary school through secondary school. Br J Dev Psychol 20:259–280

Perren S, Alsaker FD (2006) Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 47:45–57

Pronk J, Lee NC, Sandhu D, Kaur K, Kaur S, Olthof T, Goossens FA (2017) Associations between dutch and indian adolescents’ bullying role behavior and peer- group status: Crossculturally testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Int J Behav Dev 41:735–742

Pulgar J, Candia C, Leonardi PM (2020) Social networks and academic performance in physics: Undergraduate cooperation enhances ill-structured problem elaboration and inhibits well-structured problem solving. Phys Rev Phys Educ Res 16:010137

Pulgar J, Ramírez D, Candia C (2023) Enhanced social connectivity in hybrid classrooms versus academic centrality in online settings. Phys Rev Phys Educ Res 19:020155

Pulgar J, Ramírez D, Umanzor A, Candia C, Sánchez I (2022) Long-term collaboration with strong friendship ties improves academic performance in remote and hybrid teaching modalities in high school physics. Phys Rev Phys Educ Res 18:010146

Ramírez D, Guzman-Lavın EJ, Pulgar J, Candia C (2023) Affinity-based groups in secondary education: Increased stability at the expense of collaboration. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.15212

Reijntjes A, Vermande M, Goossens F, Olthof T, van de Schoot R, Aleva L, van der Meulen M (2013) Developmental trajectories of bullying and social dominance in youth. child abuse neglect. Child Abus Negl 37:224–234

Rivera-Hechem M, Guzmán R, Rodríguez-Sickert C, Gelcich S (2021) Effects of experience with access regimes on stewardship behaviors of small-scale fishers. Conserv Biol 35:1913–1922

Salmivalli C (2010) Bullying and the peer group: a review. Aggress Violent Behav 15:112–120

Savahl S, Montserrat C, Casas F, Adams S, Tiliouine H, Benninger E, Jackson K (2019) Children’s experiences of bullying victimization and the influence on their subjective well-being: a multinational comparison. Child Dev 90:414–431

Schwartz D (2000) Subtypes of victims and aggressors in children’s peer groups. J Abnorm child Psychol 28:181–192

Schwartz D, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE (2000) Friendship as a moderating factor in the pathway between early harsh home environment and later victimization in the peer group. Dev Psychol 36:646

Sutton J, Keogh E (2000) Social competition in school: relationships with bullying, machiavellianism, and personality. Br J Educ Psychol 70:443–456

Tani F, Greenman P, Schneider B, Fregoso M (2003) Bullying and the big five. a study of childhood personality and participant roles in bullying incidents. Sch Psychol Int 24:131–146

Thurston A, Cockerill M, Craig N (2019) Using cooperative learning to close the reading attainment gap for students with low literacy levels for grade 8/year 9 students. Int J Educ Res 94:1–10

Tippett N, Wolke D (2014) Socioeconomic status and bullying: a meta-analysis. Am J public health 104:e48–e59

Vaillancourt T, Hymel S, McDougall P (2003) Bullying is power: implications for school-based intervention strategies. J Appl Sch Psychol 19:157–176

Van Ryzin M, Roseth C (2019) Effects of cooperative learning on peer relations, empathy, and bullying in middle school. Aggress Behav 45:643–651

Varela JJ, Fábrega J, Carrillo G, Benavente M, Alfaro J, Rodríguez-Sickert C (2020) Bullying and subjective well-being: a hierarchical socioeconomical status analysis of chilean adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev 118:105398

Varela JJ, Sirlopú D, Melipillán R, Espelage D, Green J, Guzmán J (2019) Exploring the influence school climate on the relationship between school violence and adolescent subjective well-being. Child Indic Res 12:2095–2110

Yamagishi T and Cook K (1993) Generalized exchange and social dilemmas. Soc Psychol Q 235–248

Young-Jones A, Fursa S, Bykert J, Sly J (2015) Bullying affects more than feelings: the long-term implications of victimization on academic motivation in higher education. Soc Psychol Educ 18:185–200

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CRS, CM, and CC conceived the idea and designed the experiments. VL and TY performed the experiments and collected data. VL and CC processed the experimental data and analyzed data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and the results. CC wrote the manuscript in collaboration with VL, JP, and CRS. This work was jointly supervised by CC and CRS. All authors thoroughly reviewed and approved the manuscript. This research was supported by ANID FONDEF IT15I10079. Cristian Candia was supported by ANID FONDECYT Iniciación 11200986 and Carlos Rodriguez-Sickert was supported by ANID FONDECYT 1230489.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data collection methods and experimental protocol were approved on 4 May 2016, by the human subjects review board of Universidad del Desarrollo (IT15I10079).

Informed consent

Informed consent was secured from the Directors of each participating school prior to the commencement of the experiment. Additionally, the data utilized in this study was collected exclusively from students whose tutors, acting in their capacity as legal guardians, expressly permitted their participation in the research. This consent process ensured that all parties were fully aware of the nature, purpose, and potential implications of the experiment, in accordance with ethical guidelines and regulations.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Landaeta-Torres, V., Candia, C., Pulgar, J. et al. Game theory in the classroom: low cooperative relationships identify bullying patterns in elementary schools. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1101 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03493-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03493-5