Abstract

This study examines the impact of conspicuous consumption on environmentally sustainable fashion brands (ESFBs). Most previous studies have been limited to environmental perspectives; however, research on environmental behavior by conspicuousness has been lacking. This study views the brand as a tool for revealing oneself and examines the moderator brand–self-connection. It utilized a structural equation model with 237 valid questionnaires. Its findings are as follows: (1) Conspicuous consumption, fashion trend conspicuousness, and socially awakened conspicuousness positively affect the word-of-mouth (WOM) marketing of ESFBs. (2) Environmental belief is fully mediated by the environmental norm (EN) and does not directly affect WOM. (3) The more consumers are consistent with ESFBs, the stronger their WOM marketing. They are moderated only by the EN and socially awakened conspicuousness. (4) A higher fashion trend conspicuousness is associated with increased WOM marketing, indicating that such brands are frequently used as a method of self-expression. This study highlights consumers’ socially awakened conspicuousness and fashion trend conspicuousness in relation to ESFBs and discusses some implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The emergence of sustainable consumption as a new trend can be attributed to the growing environmental consciousness (Kerber et al. 2023; Zameer and Yasmeen, 2022). This is evident in the increasing involvement of fashion brands in the Fashion Pact, a global agreement aimed at promoting environmental sustainability (The Fashion Pact, 2023). Patagonia, a company renowned for its commitment to sustainability, conducts various activities under its corporate motto, such as using 98% recycled material and sourcing electricity from 100% renewable sources while maintaining its top position in the outdoor apparel market (Alonso, 2023). Additionally, non-apparel industry brands have embraced the pursuit of sustainability. Freitag, a fashion industry brand that produces recycled bags from used truck tarps, has continued to gain popularity over the past three to four years (Ga, 2022). Since its launch in 2017 specializing in pleated knit bags crafted from recycled yarn derived from discarded plastic bottles, Pleats Mama has experienced an annual growth rate of 150% on average (Kim, 2022a). In response to the climate change crisis, which is exacerbated by global warming, even luxury brands such as Burberry, Prada, and Gucci have begun incorporating sustainable fashion products into their collection. Consequently, within the last five years, approximately 30% of consumers have increased their purchase of sustainable products, resulting in a 32% increase in the market share of these products (Ruiz, 2023; Tighe, 2023). In summary, brands such as Patagonia, Freitag, and Pleats Mama, which prioritize environmental sustainability, article are gaining prominence (Little, 2022). This is due to the growing enthusiasm of consumers towards these brands’ environmental sustainability initiatives.

Even if a given brand does not explicitly focus on environmental sustainability, environmental values and beliefs significantly influence consumers’ purchasing decisions, according to research on sustainable fashion (Apaolaza et al. 2022; Bianchi and Gonzalez, 2021; Park & Lin, 2020). Moreover, studies demonstrate that consumers are increasingly resorting to luxury and fast fashion brands—often regarded as the major contributors to environmental pollution—for environmental reasons. This trend is attributable to these brands’ effective sustainable marketing strategies (Neumann et al. 2020; Stringer et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2021). In other words, through their marketing strategies, these brands are successfully positioning themselves as sustainable choices, which results in meaningful purchase intentions among consumers.

However, these previous studies do not consider fashion’s symbolic function or social meaning. By wearing sustainable fashion brands, consumers seek to demonstrate their commitment to environmental beliefs(EBs). Consumer behavior toward sustainable fashion is not driven by EBs. For other reasons, the purchase is made in a conspicuous context (Legere & Kang, 2020; Stringer et al. 2020). Numerous studies have documented this phenomenon, with a particular focus on certain conspicuous activities in philanthropic research. Generally known as comprising actions that are motivated by altruistic values, philanthropy is currently being evaluated in terms of its sustainability. For instance, the mission of Or Foundation, a public charity based in the USA, is to establish an alternative model of ecological prosperity (Wong, 2023). In fact, private philanthropy has been found to play a key role in sustainable development (Gautier and Pache, 2015; Porter and Kramer, 2002). However, although such actions spring from good intentions, they also involve certain aspects that are determined by motives other than altruism. That is, philanthropic research indicates that these endeavors are frequently associated with a desire for recognition and respect (De Dominicis et al. 2017; Grace and Griffin, 2009; Wallace et al. 2017). This behavior may stem from a conspicuous desire to be acknowledged by others for social awareness and to receive praise and validation from followers, particularly when such actions are shared on social networking sites (SNS) (e.g., the ice bucket challenge and bracelets for Japanese military sexual slavery grandmothers). Intending to gain respect from others, individuals tend to engage in acts that may be considered as “displaying” or “showing off,” even in the case of eco-friendly purchases and environment-related word-of-mouth (WOM) behavior.

Conspicuousness is evident in less visible charitable activities and fashion products with higher visibility and symbolic value. Regarding luxury fashion products, including those that incorporate sustainable marketing strategies, consumers may still prioritize luxury symbols for their conspicuousness, despite the significance of sustainable beliefs (Ki and Kim, 2016; Mishra et al. 2023). Consequently, it is essential to investigate whether conspicuous consumption occurs concerning environmentally sustainable fashion brands (ESFBs) rather than luxury brands. By publicly displaying one’s decision to wear an ESFB, one can establish oneself as a socially conscious individual and a fashion leader, potentially leading a new consumption trend or gaining a following. Hence, it is crucial to examine whether consumers’ choices are driven by sustainable beliefs or constitute conspicuous behavior. Consumers want to express themselves through the meaning of a brand. They believe that they “connect” with a brand and choose to wear it for its meaning (Escalas, 2004; Escalas and Bettman, 2003). Therefore, the more one connects to a brand, the more one can actively wear it to express one’s beliefs. The study’s research questions are formulated as follows:

RQ1. Do consumers truly engage in WOM behavior in relation to ESFBs based on EBs? Do they have no conspicuous intentions?

RQ2. As brands express self-concept, do consumers reinforce WOM behavior to support environmental norms (ENs) and reveal their EBs? What role does the self-brand connection of ESFB consumers play if conspicuous intentions exist?

This study aims to examine the effect of conspicuousness on consumer behavior concerning ESFBs, a topic that is yet to be examined. Conspicuousness is specifically subdivided into that of the fashion trend leader and that of a socially awakened person. Consumers who utilize ESFBs as a means of expressing their identity are confronted with the decision of whether to reinforce environmental behavior or conspicuous behavior. As a result, we must identify consumers’ purchasing motives for ESFBs and flesh out their implications.

Literature review

Environmental sustainability

Our Common Future, which defines sustainability, posits environmental sustainability as one of the three concepts of sustainable development (society, economy, environment) (Brundtland, 2013). Environmental sustainability can be defined as the “maintenance of natural capital,” which involves at least the reduction of the level of resource use or depletion of environmental assets (Goodland, 1995). In the aftermath of global warming, concerns regarding the sustainability of natural resources have intensified due to global boiling (Arora and Mishra, 2023). Accordingly, environmental sustainability is becoming more important than it was before. According to Morelli (2011), sustainability is “good” and is frequently abused for expertise or contributions in a certain field, regardless of the actual effects exerted on the natural environment or ecological health. Environmental sustainability should be viewed as an essential human activity for supporting the ecosystem based on sound ecological concepts. Goodland (1995) describes environmental sustainability as a set of constraints, involving “the use of renewable and nonrenewable resources on the source side, and pollution and waste assimilation on the sink side” (p. 10). Most research on environmental sustainability focuses on exploring what should be done from an environmental perspective (Ögmundarson et al., 2020; Koul et al., 2022) and the impact each country has on the environment (Yang and Khan, 2022; Yang et al., 2022). In addition, environmental sustainability is a crucial consideration in business decision-making because it involves finding a balance between economic productivity and minimizing environmental impact (Lou et al., 2022). One of these is the study of secondhand consumption (Cuc & Vidovic, 2014; Xue et al. 2018). Although many companies claim to prioritize sustainability, they often focus on economic and social sustainability rather than issues of environmental sustainability (Brydges et al. 2022). Environmental sustainability is frequently compromised in this way for marketing strategies (Salnikova et al, 2022; Vesal et al. 2021; Villalba‐Ríos et al. 2023) or for achieving environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) (Khalil & Khalil, 2022; Prömpeler et al. 2023). Consumers are no longer fooled by sustainability marketing, which they perceive as greenwashing (Kahraman and Kazançoğlu, 2019; Nguyen et al. 2021). Accordingly, consumers base their purchases on their knowledge and awareness of brands that advocate environmental activism rather than merely participating in greenwashing (Venkatesan, 2022).

Sustainable fashion

Regarding environmental sustainability, the fashion industry encounters significant challenges because it consumes substantial amounts of water, energy, and chemicals while generating disposal problems (Lou et al., 2022). At a time when consumer demand for ESG is increasing, various sustainable fashion initiatives have emerged in the industry. Various green branding and eco-labeling initiatives, as well as sustainable logistics practices, have been implemented (Sandberg and Hultberg, 2021). H&M and Zara, representative fast fashion brands, are also implementing various sustainable strategies in line with this trend (Dzhengiz et al. 2023; Rathore, 2022). The growing platform for secondhand fashion after the COVID-19 pandemic serves as a representative example (Kim and Kim, 2022). However, many consumers view sustainability assertions in the fashion industry as mere marketing strategies (i.e., greenwashing) and express doubts about the genuineness of these efforts (Szabo and Webster, 2021). Brydges et al. (2022) have also examined the communication strategies employed by fashion companies and found that consumers perceive these strategies as a form of greenwashing aimed at selling sustainability. These concerns have made certain fashion brands, such as Freitag and Patagonia, shift their focus to environmental sustainability. To evaluate the impact of sustainability, Patagonia specifically established the Sustainable Apparel Coalition (SAC) and spearheaded efforts to develop the Higg Index. This company has developed new processes to address environmental issues and prioritized recycling fibers and using recycled textiles to reduce their landfill waste (Bhuiyan et al. 2023; Pandey et al. 2020). Consumers are actively supporting and consuming brands that genuinely prioritize environmental sustainability as opposed to merely engaging in greenwashing practices. Consumption is increasing for ESFBs that adhere to the “maintenance of natural capital” (Rathore, 2022). However, focus on consumer behavior toward ESFBs is still lacking; thus, it is necessary to investigate consumer perceptions and behaviors concerning these brands.

Hypothesis development

Environmental beliefs and norms

Consumers are cognizant of the seriousness of environmental pollution and are actively implementing eco-friendly actions. EBs are unshakeable beliefs or attitudes that guide individuals to decide to protect the environment (Gray et al., 1985). Inglehart (1995, 1997) asserted that as the economy develops and modernizes, EB emerges because people are concerned about the environmental state. Thus, developed country consumers are likely to recognize ESFBs and consume them, knowing that the promotion of various sustainable brands is a marketing strategy (greenwashing) due to the high EB. Environmental norm (EN) is an important and strong motivating factor that influences environmental behaviors and signifies a sense of responsibility or moral obligation to the environment. Additionally, activated and internalized EB helps in overcoming obstacles to individual behavior based on a sense of duty (Babcock, 2009). These EBs and ENs are mainly used for research on eco-friendly behaviors, especially those grounded in Stern’s (2000) value-belief-norm (VBN) theory. Based on the VBN theory, it is hypothesized that individuals with strong environmental values and norms are more likely to engage in sustainable consumption practices, thereby resulting in better environmental behaviors. Additionally, it is expected that consumers in developed countries will exhibit a greater propensity to recognize greenwashing and to consider environmental values and norms, especially when purchasing from environmentally sustainable fashion brands (ESFBs). Furthermore, it is widely believed that ENs serve as a crucial mediator in the relationship between EBs and eco-friendly behaviors, as supported by previous research in areas such as green cosmetics and green hotels (Jaini et al., 2020; Ruan et al., 2022).

The hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis (H1). EB positively affects EN.

WOM plays a vital role in shaping consumer attitudes and purchasing behavior (Yang et al, 2012). Furthermore, with the widespread use of SNS, e-WOM has enabled consumers to easily access evaluations and opinions about various products and services. WOM is a widely applied factor in marketing, and 61% of key marketers select it as one of the most effective marketing tools (Berger, 2014). Consumers are gradually adopting more environmentally conscious purchasing practices as their awareness of the environmental impact of their purchasing decisions grows. Specifically, it has been discovered that the acquisition of diverse environmental information through SNS platforms contributes to the growth of pro-environmental behavior (Jain et al. 2020). The WOM intention for eco-friendly products refers to the communication between consumers and other people or groups (such as social channels, friends, and relatives.) of experiences about the purchase of such products (Chaniotakis and Lymperopoulos, 2009). A significant correlation, according to Chun et al. (2018), exists between environmental value, belief, attitude, and WOM intention for upcycling products. Gatersleben et al. (2002) assert that EB can be formed through value awareness and lead to specific behavioral intentions. According to Panda et al. (2020), environmental sustainability awareness positively impacts both green purchase intention and green brand evangelism. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated that EBs directly influence pro-environmental behavioral intentions and attitudes toward ecotourism (Li et al. 2021; Nguyen & Le, 2020). As noted in prior research on VBN theory, ENs impact environmental behavior (Stern et al. 1999; Stern, 2000). Certain studies have examined the influence of norms on predicting pro-environmental attitudes. According to Jansson et al. (2010), EB, EN, and habit influence Swedish consumers’ willingness to purchase green products. Bakti et al. (2020) found that different norms (subjective, moral, environmental) affect the WOM regarding the use of public transportation for environmental reasons. Hence, both EBs and ENs significantly influence the WOM behavior toward a brand.

Hypothesis (H2). EB positively affects WOM.

Hypothesis (H3). EN positively affects WOM.

Conspicuousness on WOM

The goal-framing theory, proposed by Lindenberg (2000, 2001, 2008), elucidates how goals influence human perception, thoughts, and decision-making processes. According to this theory, human needs can be categorized into three types: gain goals, which involve knowledge and information acquisition; normative goals, which emphasize appropriate behavior based on social norms; and hedonic goals, which prioritize perceived pleasure. In each situation, one goal is typically prioritized over the others; these goals coexist and form a frame through mutual competition. Lindenberg and Steg (2007) applied the goal-framing theory to explain pro-environmental and pro-social behaviors. They proposed that individuals who prioritize the normative goal are increasingly likely to engage in eco-friendly actions. In contrast, those who prioritize gain and hedonic goals may engage in non-eco-friendly behaviors. This theory has been utilized to support research on various consumer behaviors, including those influenced by environmental beliefs, norms, and other goals and motivations (Mishra et al., 2023; Yang et al. 2020). Additionally, the pursuit of hedonic goals can explain why consumers pursuing conflicting goals, including normative goals for eco-friendly behavior, may still engage in eco-friendly actions. Liobikienė and Juknys (2016) contended that individuals with hedonic goals may occasionally engage in environmentally friendly behavior with pleasure and joy. Mishra et al. (2023) examined the use of the luxury sharing economy in emerging markets. They found that consumer behavior was significantly influenced by the hedonic goal of conspicuousness.

Previous research discovered that conspicuous consumption has a static effect on sustainable clothing purchase intention (Apaolaza et al. 2022; Hammad et al. 2019). Because sustainable fashion products are fashion goods, they have the characteristics of fashion, such as trends, styles, and symbols. Unlike other sustainable products, a fashion product cannot ignore the attributes of fashion. Clothing is especially used as a means of self-expression. This is because the values and thoughts conveyed through clothing are symbolic and communicate meaning to others. Prior research on sustainable fashion has examined aspects of flaunting one’s social status and showcasing the latest trends in fashion. Additionally, Cervellon and Shammas (2013) validated the conspicuousness of the symbol of sustainable luxury products. A pursuit of personal style, as demonstrated by Ki and Kim (2016) enables consumers to make sustainable luxury purchases. The study on sustainable fashion consumption conducted by Lundblad and Davies (2016) also identified self-expression as a significant determinant. Therefore, showcasing an eco-friendly image, which involves being socially awake and positioning oneself as a fashion leader, can affect WOM, an active eco-friendly purchasing behavior. The following hypotheses can be made:

Hypothesis (H4). Fashion trend conspicuousness (FTC) positively affects WOM.

Hypothesis (H5). Social awaken conspicuousness (SAC) positively affects WOM.

Self-brand connection

Self-concept serves as the foundation for symbolic consumption; it originates from the motivation of self-enhancement and maintenance of self-esteem, which express individual values and is interpreted as behavior for social adoption (Greenwald & Farnham, 2000; Shavitt, 1990). Consumers feel a “sense of self-definition” by consuming products and services and communicating about them to others. That is why they identify with a brand and prefer a brand that can reflect and express their self-concept. In other words, consumers may use a brand as a physical representation of themselves to establish a connection with it; this is known as self-brand connect (SBC) (Escalas, 2004; Escalas and Bettman, 2003).

SBC positively correlates with behavioral intention, such as brand choice and loyalty, as well as brand attitudes (Escalas, 2004, Moore and Homer, 2008; Naletelich and Spears, 2020). When the self-image aligns with the brand’s image is congruent, and when the brand can protect and enhance the self-image, there will be an increase in purchases and loyal customers for the brand. In addition, in comparison to consumers with low SBC, those with strong SBC utilize the brand primarily for self-expression, have more favorable evaluations of the brand, and have higher behavioral intentions. Conversely, consumers with low SBC tend to have low motivation to express their true selves through the brand and have a low attachment to the brand (Ferraro et al. 2013).

Consumers are increasingly cognizant of the issue of greenwashing, which is not truly sustainable, and are reluctant to purchase greenwashing brands (Apaolaza et al. 2022). The more consumers believe they are eco-friendly, the more likely they are to perceive a sustainable brand as greenwashing and passionately consume more environmentally sustainable brands. In other words, consumers must establish a profound emotional bond with the ESFB that reflects their eco-friendly beliefs and images. Therefore, consumers who express their environmental identity with environmentally sustainable brand (ESB) can be expected to reinforce eco-friendly behavior. The following hypotheses can be made:

Hypothesis (H6a). SBC moderates between EB and WOM

Hypothesis (H6b). SBC moderates between EN and WOM

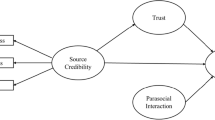

Consumers utilize the brand’s symbolism to show off their identity. Apaolaza et al. (2022) asserted that a sustainable brand can increase purchase intention through conspicuousness when perceived as useful. In other words, if the utility of revealing one’s identity increases, the possibility of consumption behavior such as WOM increases. Meanwhile, if ESFBs represent their identity, but have a strong motivation to reveal that they are socially aware of eco-friendliness, then it is likely to be used as a means of conspicuousness. The following hypotheses can be made (Fig. 1):

Hypothesis (H6c). SBC moderates between FTC and WOM

Hypothesis (H6d). SBC moderates between SAC and WOM.

Methods

Sample and data collection

The survey focused on fashion brands that prioritize environmental sustainability. First, the concept of ESFBs was explained to university students in the classroom, and brands were recommended to them. The process of brand selection involved considering the definition of environmental sustainability, which we established as the “maintenance of natural capital.” In doing so, we assessed each brand according to the information provided on their websites regarding their corporate philosophy and manufacturing method. Specifically, brands that promote recycling, reusing, and reclaiming, such as utilizing recycled polyethylene terephthalate yarn or repurposing discarded materials, were selected. To confirm whether the selected brand was suitable to be classified as an ESFB, two professors and three doctoral students confirmed the definition of ESFB and face validity. After checking the current awareness of the selected brands using a preliminary survey of 28 graduate students, three brands were ultimately selected as ESFBs in descending order of popularity: Patagonia (USA), Pleat Mama (Korea), and Freitag (Switzerland). Considering Korea’s tendency for other-oriented consumption, questionnaires were administered to Korean individuals aged between 20 and 40 years (Park et al., 2008). This demographic was considered suitable for examining tendencies toward conspicuous consumption of ESFBs. The survey focused on the participants’ purchasing experiences or intentions regarding Patagonia, Pleat Mama, and Freitag. The online survey required participants to indicate whether they had experience purchasing the brands in the past before proceeding to the main question. If they had no prior purchase experience with the brands in question, respondents were further asked regarding their purchase intention toward the brands. Only those with high scores proceeded to the main question. Furthermore, the survey was restricted to respondents who recognized the three brands in question as ESFBs. Data was collected through e-mail, facilitated by an online survey company, which also motivated the participants with rewards. Out of the initial 260 respondents who completed the questionnaire, 237 responses were considered reliable after removing the inconsistent or unreliable responses.

Respondents’ characteristics

The demographics of the 237 sampled respondents are as follows: 17.7% were in their 20 s, 37.6% were in their 30 s, and 44.7% were in their 40 s. The average age of 37.37 years was recorded. Of the respondents, 18.1 and 81.9% were men and women, respectively. Several previous studies have exhibited gender effects on sustainable consumption, indicating that women are more active than men (Bloodhart and Swim, 2020; Kim, 2022b). As such, instead of following the population ratio, it can be argued that the sample in this study is representative of the market segment. Of the respondents, 90.7% had a high level of educational background, with the majority holding master’s degrees. The average monthly clothing expenditures of the respondents were $50–100 (37.1%) and $100–200 (27.8%). Table 1 provides more details.

Measurement

In this study, the measurement tools used to identify sustainable fashion WOM, such as belief, concern, and conspicuousness, are as follows. EB scale and EN both consisted of six questions, following Stern (2000). FTC was composed of three items, as stated by Ki and Kim (2016). SAC was composed of four items, following Grace and Griffin (2009), while WOM for consumer brands was also four items, as described by Molinari et al. (2008). Six items were in SBC, following van der Westhuizen (2018). All items were measured utilizing a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The final section was composed of questions regarding demographic information (Table 1).

Results

Measurement validity and reliability

Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), which is an efficient method for predicting latent variables, minimizes estimation errors. In contrast, AMOS-based SEM, which is covariance-based, is more suitable for analyzing and testing theories in the social sciences (Dash and Paul, 2021; Mia et al. 2019). Furthermore, the basic assumption of AMOS entails a normal distribution with a minimum sample size of 200 or more, and this is satisfied by this study. Additionally, AMOS (CB-SEM) utilizes the maximum likelihood estimation that is significant to the parameter estimation (Stevens, 2009; Westfall and Henning, 2013). To verify the reliability and validity of the measurement variables used here, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis (Table 2). The model exhibited an acceptable fit: GFI = 0.908; CFI = 0.969; NFI = 0.928; RMR = 0.033; RMSEA = 0.055; χ2 = 233.328 (df = 137); p < 0.000; normed χ2 = 1.703. All the items in the model were significant. To verify the convergence validity of the measurement model, we confirmed the significance levels of the average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and factor loading (Hair et al., 2010). The factor loading of the measurement variable was significant at the 1% level. The AVE and CR values were 0.519–0.790 and 0.764–0.933, respectively; these values are considered high. The Cronbach’s α, which measures reliability, was more than 0.7; thus, internal consistency was confirmed.

Discriminant validity was measured in this study using Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) recommendations suggested. It refers to a state in which researchers identify that each indicator of a theoretical model differs statistically. It can be calculated by comparing AVE with squared correlations. It is supported when the AVE among each pair of constructs is greater than Φ2 (i.e., the squared correlation between two constructs) (Table 3).

Hyperthesis testing

To verify our hypotheses, we performed an analysis of the covariance structure model. The results are illustrated in Fig. 1. The hypothesized structural model generated a good fit (χ2 = 106.982, df = 82, p = 0.033, Normed χ2 = 1.305, GFI = 0.945, CFI = 0.987, RMR = 0.029, TLI = 0.984, RMSEA = 0.036). EB positively affected EC (β = 0.783, p < 0.000); thus, H1 was supported. The structural model analysis indicated that EB was not affected by WOM (β = −0.160, p = 0.223). Thus, H2 is rejected. EC positively affected WOM (β = 0.265, p < 0.05); thud, H3 is supported. FTC (β = 0.219, p < 0.01) and SAC (β = 0.545, p < 0.001) positively affected WOM; thus, H4 and H5 are supported. The outcomes of the hypothesis testing are presented in Table 4.

Moderating effect of self-brand connection

The results of the chi-square difference test between the unconstrained model and the measurement weight model were Δχ2 = 21.970, df = 13, and p = 0.059. The non-significant change in model fit indicated that the factor loadings were invariant between the two groups, confirming the full measurement-invariance model. For SBC with an EB-WOM link, no significance was detected for the high (β = -0.221, p = 0.240) and low (β = −0.174, p = 0.317) groups, and no significant differences in path strength were detected by SBC(Δχ2 = 0.053, p > 0.05). The effect of EN on WOM was significant for high (β = 0.406, p < 0.05) and low (β = 0.188, p = 0.343) groups, while those with high EN(Δχ2 = 5.049, p < 0.05) were significantly stronger. For SBC with an FTC-WOM link, no significance was detected for the high (β = 0.059, p = 0.638) and low (β = 0.337, p < 0.01) groups, and no significant differences in path strength were detected by SBC(Δχ2 = 3.170, p > 0.05).

The effect of SAC on WOM was significant for the high (β = 0.691, p < 0.000) and low (β = 0.174, p = 0.121) groups, while those with high SAC (Δχ2 = 4.713, p < 0.05) were significantly stronger. Thus, H6a and H6c were rejected, whereas H6b and H6d were found to be moderate between EN/SAC and WOM in this study (Table 5).

Discussion

As sustainability is perceived as a marketing strategy, greenwashing, many consumers are engaging in consumption behavior toward true ESFBs. Previous studies on sustainable brands did not focus on ESFB, which concentrates on “maintenance of natural capital” such as fiber recycling and the use of recycled fibers. Particularly, fashion products have a way of showing off as symbolism; therefore, studies are focusing on sustainable fashion brands. However, it is necessary to examine whether conspicuousness exists in ESFB. Our findings were as follows:

First, both conspicuous consumption, FTC and SAC, positively impacted ESFB’s WOM. This is a remarkably interesting result, inducing consumer behavior even more strongly than EB. Due to greenwashing, consumers are more enthusiastic about ESFB than sustainable brands. However, this also confirms that consumers choose ESFB to show off as socially advanced and awakened persons. Showing off as a person who is more aware of the environment than others constitutes WOM. This was also chosen by ESFB as a way to flaunt themselves, and it can be viewed in the same context as the previous conspicuousness of charity. ESFB was also discovered to possess an inherent fashion attribute, in addition to the FTC. This is believed to be because ESFBs possess fashion characteristics. Because of the presence of visibility and symbolism, which are the characteristics of fashion, wearing an ESFB can convey the symbol and value of those brands to the observer. This phenomenon is consistent with previous sustainable fashion research (Apaolaza et al. 2022; Cervellon and Shammas, 2013; Hammad et al. 2019). In other words, consumers can show off themselves as socially awakened beings by wearing an EFSB and as trailblazers in fashion trends. Therefore, it will be necessary for a sustainable fashion company to not only put an emphasis on sustainability but also endeavor to reflect the latest fashion trends. Furthermore, brands’ self-image conspicuousness requirements must be met.

Second, it was established that EB had no direct effect as a factor that influenced ESFB’s WOM. This result contradicts the finding that EB directly affects pro-environmental behavior (Li et al. 2021; Nguyen & Le, 2020). However, in addition to the relationship between EN and EB, as proposed by Stern et al. (1999) and Stern (2000) in their VBN theory, ESBN further validates the indirect effect that EB causes behavior through EN. It also supports the goal-framing theory, which posits that normative goals further enhance pro-environmental behavior (Lindenberg and Steg, 2007). Because EN is the only way to act eco-friendly, it can be confirmed that consumers should focus more on EN rather than EB, notwithstanding the quality of ESFB.

Third, it was discovered that the strength of WOM increased with the degree of ESFB consistency and only moderated in EN and SAC. EN was a norm that was influenced by surroundings. When engaging in WOM communication by EN companies, consumers who strongly identify with eco-friendly values are more likely to participate in WOM actively. This can reveal through ESFB that they follow the norms well; thus, these actions were a means of showing one’s compliance with the norms. Through the ESFB identity, they increasingly demonstrated their commitment to eco-friendly norms.

In addition, fashion brands hold symbolic value, and higher FTC is associated with increased WOM, indicating that these brands are often used to express one’s identity. Fashion leaders who aim to showcase their fashion-forward image tend to purchase brands that align with their innovative fashion identity. This is why they prefer high-end fashion brands. However, within the framework of ESFBs, this research failed to identify any significant moderating effect between FTC and SBC. Although not statistically significant, individuals with low SBC exhibited a greater intensity of WOM. This finding contradicts previous studies (Apaolaza et al. 2022; Hammad et al. 2019), which suggested that WOM is stronger among individuals with higher fashion conspicuousness who want to showcase their identity. True sustainability is the identity associated with ESFBs. The finding that WOM is stronger among individuals who do not want to emphasize their eco-friendliness can be attributed to their desire to showcase fashion trends rather than the brand’s eco-friendliness.

This study has several academic and practical implications. First, it expands the existing research on ESFBs by examining their WOM marketing and the conspicuousness associated with consumers buying them. Although prior studies on sustainable fashion focus solely on sustainability aspects, this study acknowledges the existence of FTC and SBC as well. In future research, incorporating consumers’ FTC and SBC into the research model can enhance its explanatory power and provide a comprehensive understanding of ESFBs. Second, fashion trends must be reflected in ESFBs as well. Sustainable fashion research focuses on exploring consumer perceptions of sustainability and marketing strategies. However, as demonstrated by this study, ESFBs are still fashion brands; therefore, they appeal to consumers by staying updated with the latest trends. When consumer interest in sustainability is high, it becomes crucial to develop merchandising strategies that incorporate sustainability while simultaneously attending to the latest fashion trends. Thus, ESFBs necessarily consider prevailing trends as well. Third, this study also emphasizes the necessity of incorporating true environmental sustainability into consumer education. For example, a curriculum or training program aimed at identifying authentic ESFBs, as opposed to those that simply engage in greenwashing, will assist consumers in making informed judgments. Ultimately, this will benefit the environment by discouraging companies from engaging in greenwashing by increasing consumer awareness. Fourth, this study highlights the influence of SBC on ESFBs. Although philanthropy has been extensively studied, the significance of SBC in the context of ESFBs cannot be overlooked. Companies that focus on ESFBs must consider their role in society and strategically utilize SBC, making it more than just a fashion or environmental strategy. Fifth, this study proposes that individuals who are more sensitive to the attention of others are more likely to engage in WOM marketing for ESFBs, with consequences for companies. Moreover, advertising campaigns that capitalize on the identity of individuals who have a strong connection to ESFBs have the potential to exert an effective influence. Lastly, companies that actively pursue social and economic sustainability, rather than environmental sustainability, can prevent consumers’ misunderstanding of greenwashing, especially if they actively implement other sustainability marketing strategies instead of emphasizing ambiguous environmental aspects. In addition, conspicuous consumption promotes social sustainability; therefore, it must be utilized.

This study has a few limitations and provides suggestions for future research. First, an insufficient amount of exploration was conducted on ESFBs. Conducting quantitative research to understand consumer rationale behind the definition of ESFBs and perceptions could provide valuable insights. Therefore, qualitative studies that explore various aspects of conspicuousness related to ESFBs may yield more comprehensive and explanatory results.

Second, to measure SBC, we relied on a simple connection with eco-friendly brands. This may have led to contrasting results when considering fashion-related variables as moderators. Future research could consider refining the measurement of SBC by incorporating more comprehensive and nuanced indicators. Additionally, utilizing qualitative research methods, such as phenomenological studies, could provide a more in-depth exploration of consumer conspicuousness, leading to a broader and more intriguing range of findings concerning ESFBs. This approach may reveal a positive relationship between SBC and fashion-related variables.

Lastly, due to the specific target population of the survey, the generalizability of the findings is limited. The results may have been influenced by the collectivist nature of the surveyed population, which tends to pay more attention to their surroundings. However, it is crucial to consider that ESFBs are also growing in individualistic cultures in the West. Therefore, future studies should investigate potential differences in conspicuousness related to ESFBs among culturally distinct groups, thereby providing insights into cross-cultural variations in the phenomenon.

Conclusions

This study highlights the importance of fashion companies recognizing the evolving consumer perceptions of sustainable consumption due to the prevalence of greenwashing marketing. It is crucial for ESBs to understand that they possess both fashion and conspicuous attributes. Therefore, these brands should incorporate these attributes into their fashion products. Specifically, they should ensure that their products reflect not only the latest fashion trends but also align with consumers’ desire for self-image conspicuousness. Consequently, even as ESBs, companies should not overlook the significance of incorporating the latest trends into their products. By launching products that integrate the pursuit of sustainability with the latest trends, these companies have the potential to build customer brand loyalty.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alonso T (2023) StrategyFactory. Retrieved from https://www.cascade.app/studies/patagonia-strategy-study. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

Apaolaza V, Policarpo MC, Hartmann P, Paredes MR, D’Souza C (2022) Sustainable clothing: why conspicuous consumption and greenwashing matter. Bus Str Env 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3335

Arora NK, Mishra I (2023) Sustainable development goal 13: Recent progress and challenges to climate action. Envir Sust 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42398-023-00287-4

Babcock HM (2009) Assuming personal responsibility for improving the environment: Moving toward a new environmental norm. Harv Envtl L Rev 33:117

Bakti IGMY, Rakhmawati T, Sumaedi S, Widianti T, Yarmen M, Astrini NJ (2020) Public transport users’ WOM: an integration model of the theory of planned behavior, customer satisfaction theory, and personal norm theory. Trans Res Proc 48:3365–3379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2020.08.117

Berger J (2014) Word of mouth and interpersonal communication: a review and directions for future research. J Consum Psychol 24(4):586–607

Bhuiyan MR, Ali A, Mohebbullah M, Hossain MF, Khan AN, Wang L (2023) Recycling of cotton apparel waste and its utilization as a thermal insulation layer in high performance clothing. Fash Text 10:22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-023-00342-y

Bianchi C, Gonzalez M (2021) Exploring sustainable fashion consumption among eco-conscious women in Chile. Int Rev Ret Distr Cons Res 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2021.1903529

Bloodhart B, Swim JK (2020) Sustainability and consumption: what’s gender got to do with it? J Soc Issues 76(1):101–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12370

Brundtland G (2013) Our common future. In: Tolba MK, Biswas AK (eds) Earth and US: Population–Resources–Environment–Development. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, UK, p 29–31

Brydges T, Henninger CE, Hanlon M (2022) Selling sustainability: investigating how Swedish fashion brands communicate sustainability to consumers. Sustain 18(1):357–370

Cervellon MC, Shammas L (2013) The value of sustainable luxury in mature markets: a customer-based approach. J Corp Citiz 52:90–101

Chaniotakis IE, Lymperopoulos C (2009) Service quality effect on satisfaction and word of mouth in the health care industry. Man Serv Qual 19(2):229–242. https://doi.org/10.1108/09604520910943206

Chun E, Jiang W, Yu J, Ko E (2018) Perceived consumption value, pro-environmental belief, attitude, eWOM, and purchase intention toward upcycling fashion products. Fash Text R J 20(2):177–190. https://doi.org/10.5805/SFTI.2018.20.2.177

Cuc S, Vidovic M (2014) Environmental sustainability through clothing recycling. Op Supply Chain Manag Int J 4(2):108–115. https://doi.org/10.31387/oscm0100064

Dash G, Paul J (2021) CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 173:121092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121092

De Dominicis S, Schultz P, Bonaiuto M (2017) Protecting the environment for self-interested reasons: altruism is not the only pathway to sustainability. Front Psychol 8:1065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01065

Dzhengiz T, Haukkala T, Sahimaa O (2023) (Un) Sustainable transitions towards fast and ultra-fast fashion. Fash Text 10:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40691-023-00337-9

Escalas JE (2004) Narrative processing: Building consumer connections to brands. J Consum Psychol 14(1):168–180

Escalas JE, Bettman JR (2003) You are what they eat: the influence of reference groups on consumers’ connections to brands. J Consum Psychol 13(3):339–348

Ferraro R, Kirmani A, Matherly T (2013) Look at me! Look at me! Conspicuous brand usage, self-brand connection, and dilution. J Mark Res 50(4):477–488

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Ga S (2022) Freitag, Living a Second Life as a Bag, Not Just Trash. CNUPress. https://press.cnu.ac.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=15986. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

Gatersleben B, Steg L, Vlek C (2002) Measurement and determinants of environmentally significant consumer behavior. Env Behav 34(3):335–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916

Gautier A, Pache A-C (2015) Research on corporate philanthropy: a review and assessment. J Bus Ethics 126:343–369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1969-7

Goodland R (1995) The concept of environmental sustainability. Ann Rev Eco Syst 26:1–24

Grace D, Griffin D (2009) Conspicuous donation behaviour: scale development and validation. J Consum Behav 8(1):14–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.270

Gray DB, Borden RJ, Weigel RH (1985) Ecological beliefs and behaviors: Assessment and change. Bloomsbury Pub, NY, USA

Greenwald AG, Farnham SD (2000) Using the implicit association test to measure self-esteem and self-concept. J Pers Soc Psy 79(6):1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1022

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ (2010) Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed) Pearson Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

Hammad H, Muster V, El-Bassiouny NM, Schaefer M (2019) Status and sustainability: can conspicuous motives foster sustainable consumption in newly industrialized countries? J Fash Mark Manag 23(4):537–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-06-2019-0115

Inglehart R (1995) Public support for environmental protection: objective problems and subjective values in 43 societies. Pol Sci Pol 28:57–72

Inglehart R (1997) Modernization and Post Modernization: Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Jain VK, Gupta A, Tyagi V, Verma H (2020) Social media and green consumption behavior of millennials. J Content Community Commun 10(6):221–230

Jaini A, Quoquab F, Mohammad J, Hussin N (2020) “I buy green products, do you…?” The moderating effect of eWOM on green purchase behavior in Malaysian cosmetics industry. Inter J Pharma Health Mark 14(1):89–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPHM-02-2019-0017

Jansson J, Marell A, Nordlund A (2010) Green consumer behavior: determinants of curtailment and eco-innovation adoption. J Consum Market 27(4):358–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761011052396

Kahraman A, Kazançoğlu İ (2019) Understanding consumers’ purchase intentions toward natural‐claimed products: a qualitative research in personal care products. Bus Strategy Env 28(6):1218–1233. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2312

Kerber JC, de Souza ED, Fettermann DC, Bouzon M (2023) Analysis of environmental consciousness towards sustainable consumption: an investigation on the smartphone case. J Clean Prod 384:135543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.135543

Khalil MK, Khalil R (2022) Leveraging buyers’ interest in ESG investments through sustainability awareness. Sustain 14(21):14278. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114278

Koul B, Yakoob M, Shah MP (2022) Agricultural waste management strategies for environmental sustainability. Envir Res 206:112285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.112285

Ki CW, Kim YK (2016) Sustainable versus conspicuous luxury fashion purchase: applying self‐determination theory. Fam Consum Sci Res J 44(3):309–323. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcsr.12147

Kim MS (2022a) Creating a brand that adds beauty to the eco-friendliness. Platum. https://platum.kr/archives/182663. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

Kim NL, Kim TH (2022) Why buy used clothing during the pandemic? Examining the impact of COVID-19 on consumers’ secondhand fashion consumption motivations. Int Rev Retail Distrib Consum Res 32(2):151–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593969.2022.2047759

Kim YD (2022b) Gender gap in sustainable consumption behavior. J Con Pol St 53(2):171–210. https://doi.org/10.15723/jcps.53.2.202208.171

Legere A, Kang J (2020) The role of self-concept in shaping sustainable consumption: A model of slow fashion. J Clean Prod 258:120699. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120699

Li X, Yu R, Su X (2021) Environmental beliefs and pro-environmental behavioral intention of an environmentally themed exhibition audience: the mediation role of exhibition attachment. SAGE Open 11(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211027966

Lindenberg S (2001) Intrinsic motivation in a new light. Kyklos 54(2‐3):317–342

Lindenberg S (2008) Social rationality, semi-modularity, and goal-framing: what is it all about? Anal Kritik 30(2):669–687. https://doi.org/10.1515/auk-2008-0217

Lindenberg S (2000) The Extension of Rationality: Framing versus Cognitive Rationality. In: Baechler J, Chazel F, Kamrane R (eds) L’Acteur et ses Raisons. Mélanges en l’honneur de Raymond Boudon, Paris, p 168–204

Lindenberg S, Steg L (2007) Normative, gain and hedonic goal frames guiding environmental behavior. J Soc Issues 63(1):117–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00499.x

Little B (2022) what companies are doing to become more sustainable. WeWork https://www.wework.com/ideas/research-insights/research-studies/what-companies-are-doing-to-become-more-sustainable. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

Liobikienė G, Juknys R (2016) The role of values, environmental risk perception, awareness of consequences, and willingness to assume responsibility for environmentally-friendly behaviour: The Lithuanian case. J Clean Prod 112:3413–3422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.10.049

Lou X, Chi T, Janke J, Desch G (2022) How do perceived value and risk affect purchase intention toward second-hand luxury goods? An empirical study of US consumers. Sustain 14(18):11730. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811730

Lundblad L, Davies IA (2016) The values and motivations behind sustainable fashion consumption. J Cons Beh 15(2):149–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1559

Mia MM, Majri Y, Rahman IKA (2019) Covariance-based-structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) using AMOS in management research. J Bus Manag 21(1):56–61. https://doi.org/10.9790/487X-2101025661

Mishra S, Jain S, Pandey R (2023) Conspicuous value and luxury purchase intention in sharing economy in emerging markets: the moderating role of past sustainable behavior. J Glob Fash Mark 14(1):93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2022.2034029

Molinari LK, Abratt R, Dion P (2008) Satisfaction, quality and value and effects on the repurchase and positive word-of-mouth behavioral intentions in a B2B services context. J Serv Makr 22(5):363–373. https://doi.org/10.1108/08876040810889139

Moore DJ, Homer PM (2008) Self-brand connections: the role of attitude strength and autobiographical memory primes. J Bus Res 61(7):707–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.09.002

Morelli J (2011) Environmental sustainability: a definition for environmental professionals. J Env Sust 1(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.14448/jes.01.0002

Naletelich K, Spears N (2020) Analogical reasoning and regulatory focus: using the creative process to enhance consumer-brand outcomes within a co-creation context. Eur J Mark 54(6):1355–1381. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-05-2018-0354

Neumann HL, Martinez LM, Martinez LF (2020) Sustainability efforts in the fast fashion industry: consumer perception, trust, and purchase intention. Sust Acc Manag Policy J 12(3):571–590. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAMPJ-11-2019-0405

Nguyen TKC, Le TP (2020) Impact of environmental belief and nature-based destination image on ecotourism attitude. J Hosp Tour Inst 3(4):489–505. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-03-2020-0027

Nguyen TTH, Nguyen KO, Cao TK, Le VA (2021) The impact of corporate greenwashing behavior on consumers’ purchase intentions of green electronic devices: an empirical study in Vietnam. J. Asian Financ Econ Bus 8(8):229–240. https://doi.org/10.13106/JAFEB.2021.VOL8.NO8.0229

Ögmundarson Ó, Herrgård M J, Forster J, Hauschild MZ, Fantke P (2020) Addressing environmental sustainability of biochemicals. Nat Sust 3(3):167–174. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0442-8

Panda TK, Kumar A, Jakhar S, Luthra S, Garza-Reyes JA, Kazancoglu I, Nayak SS (2020) Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. J Clean Prod 243:118575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118575

Pandey R, Pandit P, Pandey S, Mishra S (2020) Recycling from Waste in Fashion and Textiles: A Sustainable and Circular Economic Approach. In: Pandit P, Ahmed S, Singha K, Shrivastava S (eds) Solutions for sustainable fashion and textile industry. Wiley & Sons, NJ, USA, p 33–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119620532.ch3

Park HJ, Lin LM (2020) Exploring attitude–behavior gap in sustainable consumption: comparison of recycled and upcycled fashion products. J Bus Res 117:623–628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jusres.2018.08.025

Park JY, Lee SH, Choi JY (2008) Influence of consumption value and beliefs on attitudes towards luxury brands. Fash Tex Res J 10(2):191–197

Porter ME, Kramer MR (2002) The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harv Bus Rev 80:56–68

Prömpeler J, Veltrop DB, Stoker JI, Rink FA (2023) Striving for sustainable development at the top: exploring the interplay of director and CEO values on environmental sustainability focus. Bus Strategy Env 32(7):5068–5082. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3408

Rathore B (2022) Supply Chain 4.0: Sustainable Operations in Fashion Industry. Int J N Med Stud 9(2):8–13

Ruan WJ, Wong IA, Lan J (2022) Uniting ecological belief and social conformity in green events. J Hosp Tour Manag 53:61–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.09.001

Ruiz A (2023) 51 Hyge environmental conscious consumer statistics. Theroundup. https://theroundup.org/environmentally-conscious-consumer-statistics/. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

Salnikova E, Strizhakova Y, Coulter RA (2022) Engaging consumers with environmental sustainability initiatives: consumer global–local identity and global brand messaging. J Mark Res 59(5):983–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222437221078522

Sandberg E, Hultberg E (2021) Dynamic capabilities for the scaling of circular business model initiatives in the fashion industry. J Clean Prod 320:128831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128831

Shavitt S (1990) The role of attitude objects in attitude functions. J Exp Soc Psychol 26(2):124–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031(90)90072-T

Stern PC (2000) New environmental theories: Towards a coherent theory of environmentally significant behaviour. J Soc Issues 56(3):407–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00175

Stern PC, Dietz T, Abel T, Guagnano GA, Kalof L (1999) A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: the case of environmentalism. Hum Eco Rev 81–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24707060

Stevens JP (2009) Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences, 5th ed. Routledge Academic, Mahwah, NJ

Stringer T, Mortimer G, Payne AR (2020) Do ethical concerns and personal values influence the purchase intention of fast-fashion clothing? J Fash Mark Manag 24(1):99–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-01-2019-0011

Szabo S, Webster J (2021) Perceived greenwashing: the effects of green marketing on environmental and product perceptions. J Bus Ethics 171(4):719–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04461-0

The Fashion Pact (2023) The fashion pact is to scale joint action toward a nature-positive & net-zero future with the appointment of Helena Helmersson as the new Co-Chair. https://www.thefashionpact.org/Press_Release_The_Fashion_Pact_May_23.pdfofsubordinatedocument. Accessed 31 May 2023

Tighe D (2023) Evolution of sustainable shopping worldwide 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1377869/global-shift-to-buying-sustainable-products/. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

van der Westhuizen LM (2018) Brand loyalty: exploring self-brand connection and brand experience. J Prod Brand Manag 27(2):172–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-07-2016-1281

Venkatesan M (2022) Marketing Sustainability: A Critical Consideration of Environmental Marketing Strategies. In: Ogunyemi K, Burgal V (ed) Products for Conscious Consumers. Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, p 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1108/978-1-80262-837-120221009

Vesal M, Siahtiri V, O’Cass A (2021) Strengthening B2B brands by signaling environmental sustainability and managing customer relationships. Ind Mark Manag 92:321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.02.024

Villalba‐Ríos P, Barroso‐Castro C, Vecino‐Gravel JD, Villegas‐Periñan MDM (2023) Boards of directors and environmental sustainability: Finding the synergies that yield results. Bus Strategy Env 32(6):3861–3886. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3342

Wallace E, Buil I, De Chernatony L (2017) When does “liking” a charity lead to donation behaviour? Exploring conspicuous donation behaviour on social media platforms. Eur J Mark 51(11/12):2002–2019. https://doi.org/10.1108//EJM-03-2017-0210

Westfall PH, Henning KSS (2013) Texts in statistical science: understanding advanced statistical methods. Taylor & Francis, Boca Raton, FL

Wong N (2023). The Rise of Sustainable Fashion: Why Eco-Friendly Clothing is Here to Stay. Vitue https://www.virtueimpact.com/post/the-rise-of-sustainable-fashion-why-eco-friendly-clothing-is-here-to-stay. Accessed 1 Dec 2023

Xue Y, Caliskan-Demirag O, Chen YF, Yu Y (2018) Supporting customers to sell used goods: profitability and environmental implications. Int J Prod Econ 206:220–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.10.005

Yang S, Hu M, Winer RS, Assael H, Chen X (2012) An empirical study of word-of-mouth generation and consumption. Mark Sci 31(6):952–963

Yang X, Chen SC, Zhang L (2020) Promoting sustainable development: a research on residents’ green purchasing behavior from a perspective of the goal‐framing theory. Sust Dev 28(5):1208–1219

Yang L, Bashiru Danwana S, Issahaku FLY (2022) Achieving environmental sustainability in Africa: the role of renewable energy consumption, natural resources, and government effectiveness-evidence from symmetric and asymmetric ARDL models. Inter J Envir Res Pub Heal 19(13):8038. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19138038

Yang X, Khan I (2022) Dynamics among economic growth, urbanization, and environmental sustainability in IEA countries: the role of industry value-added. Env Sci Pollut Res 29(3):4116–4127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-16000-z

Zameer H, Yasmeen H (2022) Green innovation and environmental awareness driven green purchase intentions. Mark Int Plan 40(5):624–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-12-2021-0457

Zhang B, Zhang Y, Zhou P (2021) Consumer attitude towards sustainability of fast fashion products in the UK. Sustain 13(4):1646. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13041646

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have worked closely together on conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, original draft preparation, and writing and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Hanyang University Institutional Review Board, Korea. (August 30, 2021/No. 202105-010-1).

Informed consent

Prior to their participation, informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study. They were provided with detailed information regarding the study objectives, procedures, potential risks and benefits, confidentiality measures, and their rights as participants. The informed consent process ensured that participants were fully aware of the nature of the study and voluntarily agreed to participate without any coercion or undue influence.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S.E., Lee, KH. Environmentally sustainable fashion and conspicuous behavior. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 498 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02955-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02955-0