Abstract

Chinese consumers have shown a strong preference for foreign brands (FBs) for many years. However, in recent years, rising patriotism has spurred Chinese consumers to source locally, indicating a shift in preference for patriotic brands (PBs). FBs operating in the world’s second-largest market are now framing their marketing strategies to appeal more to Chinese consumers. This study examines two culturally mixed co-branded product (CMCP) framing strategies: foreign × host culture (FB × PB) and host × foreign culture (PB × FB). The results show that the effects of product fit and cultural congruence on co-branding attitude for PB × FB is stronger than that of FB × PB, and the influence of brand fit on co-branding attitude for FB × PB is stronger than that of PB × FB. Additionally, the impact of the co-branding attitude on cultural sensitivity was significant for PB × FB, whereas that on product quality was significant for FB × PB. Furthermore, the effects of co-branding attitude on purchase probability were significant for both types of CMCP framing (FB × PB < PB × FB). Structural equation modeling was used to analyze the preferences of 479 Chinese consumers. This study provides significant recommendations for FBs and PBs to benefit from a strong wave of patriotism in China through culturally mixed framing and glocalization co-branding strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few years, the Chinese government has continuously promoted national pride and encouraged consumers to purchase domestic brands. Furthermore, it has enacted preferential policies that encourage local brands to compete with foreign brand (FB) rivals. National Chairman Jinping Xi’s “Made in China 2025” state-led industrial policy focuses on three goals: moving 1) from “China’s products” to “China’s brands,” 2) from “China’s speed” to “China’s quality,” and 3) from “made in China” to “designed in China” (Liu, 2016). Hence, local brands have created the foundation for developing “designed in China” products, known as Guochao (囯潮) or patriotic brands (PBs), that reflect the rise of local Chinese brand product designs incorporating cultural elements such as arts, crafts, calligraphy, and traditional patterns. This trend is a reflection of the younger generation’s profound interest in China’s culture, traditions, and domestic brands, reflecting a cultural shift towards domestic products and a celebration of the nation’s heritage. PBs are beginning to tap into opportunities for co-branding collaborations and global players’ influence across various industries, thus demonstrating the importance of understanding and embracing foreign cultures while maintaining their local identity. Such collaborations emphasize blending local cultural elements with foreign cultural symbols, which leads consumers to view the cultural mixing of PBs and FBs as producers of glocal or hybrid customized products.

A co-branding strategy in a culturally mixed environment is relevant to managers and scholars for cross-cultural learning opportunities because it evokes different psychological implications that determine consumer reactions. However, most previous studies (e.g., Torelli et al., 2011; Peng and Tian, 2016; He and Wang, 2017; Guo et al., 2019; Nie and Wang, 2019), as shown in Table 1, have focused on global brands that incorporate local identity to create a culturally mixed product (CMP) (e.g., Starbucks mooncake and Starbucks rice dumpling). Incorporating Chinese elements is a popular strategy for global brands to build brand equity in the host country’s market. However, the mechanisms influencing consumer purchasing preferences for culturally mixed co-branded products (CMCPs) remain unknown, and there are calls for academic inquiry into such marketing strategies. Accordingly, this study seeks to provide a nuanced understanding to fill the gaps in the literature on cultural mixing framing (Cui et al., 2016) through a co-branding model of an FB and the host country’s PB, namely, FB × PB (foreign × host culture) and PB × FB (host × foreign culture) and explores how such cultural mixing practices affect these two framing strategies. Additionally, as the glocalization of brands and products with appropriate cultural elements has been mostly unexplored, we question whether the combination is a good match and jointly influences positive consumer responses.

Second, according to the brand association theory (Simonin and Ruth, 1998), a co-branding strategy involves mixing and creating a good match through perceived product fit and brand fit, which are essential factors influencing consumers’ evaluation. Measuring perceived fit is vital when incorporating elements from foreign or host countries into co-branded products. However, if the perceived fit of a co-branded product is inconsistent, consumer evaluations of the product can yield negative outcomes (Ho et al., 2017). Moreover, little is known about the effects of cultural congruence as an element of perceived fit (Han et al., 2023). Acceptance of FB products is higher when consumers’ cultural elements match their cultural dispositions (Craig et al., 2005); thus, this gap in the existing literature must be filled to examine the effect of cultural congruence, advance the congruity theory, and offer valuable insights for managers.

Third, most studies on consumers’ responses (see Table 1) to CMP focus on exclusionary reactions, which result from the perception that FBs intrude (e.g., Cui et al., 2016; Peng and Tian, 2016; Nie and Wang, 2019) or contaminate (e.g., Torelli et al., 2011; Cheon et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016) host country cultures. In contrast, few studies have focused on positive consumer reactions such as perceived creativity (e.g., Chen et al., 2016; Peng and Tian, 2016), cultural compatibility (e.g., He and Wang, 2017), and cultural respect (Guo et al., 2019). The conflicting results of previous studies prompted this study to address the issue that the fit of collaboration between FB and PB is susceptible to interpreting CMCP as a result of salient host country cultural identity threats. Consumers are sometimes sensitive to their cultural nuances. Therefore, cultural sensitivity is an essential issue that needs to be studied. However, cultural sensitivity has not previously been explored as an integrative response to cultural mixing. So, we explore whether cultural sensitivity is higher when a PB is the main collaborator for host × foreign culture (PB × FB) because PBs are perceived as a more iconic brand from a host country standpoint (Holt, 2004) than FB acting as the main collaborator for foreign × host culture (FB × PB).

Finally, determining the origin of signal cues requires looking beyond a country’s mere image and applying cultural elements as signifiers of product quality perception (He and Wang, 2017), which remains an underexplored area in the co-branding setting. Li et al. (2021) state that in developing countries, consumers consider FBs to be of high quality and have a lower opinion of local brands. Therefore, it is worth investigating whether local consumers’ perceptions of PB product quality have improved through the PB × FB co-branding strategy or if FBs through FB × PB are still perceived as generally higher and superior in quality relative to PBs.

The findings of this study provide valuable insights for global companies to formulate effective glocalization strategies to attract emerging markets’ host country consumers, thus significantly contributing to the existing research landscape of international marketing. Testing the proposed cultural mixed co-branding framework using congruity theory fills a significant knowledge gap on various integrative responses (e.g., cultural sensitivity and product quality) toward CMCP.

The structure of this study is as follows. First, we provide a theoretical foundation for a literature review highlighting key variables. Second, we develop hypotheses based on these theories. Third, we test our hypotheses in China, the largest emerging market. Finally, we discuss the research findings, theoretical contributions, managerial implications, and directions for future research.

Theoretical approach and hypothesis development

Patriotic brands (PBs)

Holt’s (2004) theory of iconic brands explains the ideologies of cultural branding, where brands use cultural icons as symbols that assimilate national identity worthy of consumer admiration or respect. Iconic local brands are sources of national identity and serve as inspirational heroes (Özsomer, 2012). Patriotism, which refers to a strong attachment to one’s own country without hostility toward other nations while cooperating with other countries (Balabanis et al., 2001), is a cultural branding ideology. Li et al. (2021) define a PB as a brand that originates in its host country, embodies local icons, and represents its host country’s national pride. For instance, Brand Keys Inc. releases the United States’ 50 most PBs annually, which define PBs as those that “best embody the emotional value of patriotism” (Brown, 2022).

Gerth (2008) stated that in Chinese historical and cultural practice, the government has encouraged the movement of national products, considering purchasing China-made goods to be patriotic and emphasizing the need to support Chinese products. Consumers with high levels of patriotism are more likely to consider local brands because they feel obligated or motivated to support their country’s economy (Carvalho et al., 2019). For instance, the PB trend started when the Chinese sportswear company, Li-Ning, debuted during the New York Fashion Week of 2018. At this prestigious event, Li-Ning introduced its WuDao (悟道) collection, which is Taoism-inspired and uses the traditional Chinese colors of red and gold that match the national flag of China. The collection also embeds four Chinese characters (中国李宁), “China Li-Ning,” symbolizing China’s cultural confidence on the global stage by applying Chinese traditional culture to modern fashion. In this way, it became the benchmark brand of the Chinese nationalist trend or the symbol of a “brand proudly designed in China,” leading Chinese netizens to coin the term Guochao for this fashion trend. After the triumphant story of Li-Ning, Guochao became a top buzzword in the Chinese domestic market. The trend quickly spread from the fashion industry to various other sectors and product categories (e.g., Huawei, NIO, Perfect Daily, The Palace Museum, and HEYTEA).

Large e-commerce platforms in China, such as Tmall, Taobao, and JD.com, have also contributed significantly to the rise in the PB trend and served as major distribution channels for local brands. For example, during the country’s “618” midyear shopping festival, May 10 was designated by the State Council of China as “China Brand Day.” Tmall launched the “National Tide Action” campaign for PB products, which drove innovation and development of local brands. According to Daxue Consulting (2021), the “National Tide Action” campaign created an online buzz for fifty PBs, facilitating the awareness of brands both locally and internationally and indicating that Chinese consumers’ perception of PBs is on par with that of FBs, regardless of the country. It indicates that brands with embedded patriotism can strengthen their bonds with consumers to win their hearts, minds, and loyalty, leading them to “stand up, salute, and buy” (Passikoff, 2022).

Cultural mixing in co-branding

Cultural mixing plays a role in conjunction with brand globalness and localness symbols, which are presented simultaneously in the same space (Chiu et al., 2009). However, the cultural mixing strategy has been growing and is no longer associated with the global spread of a single culture (e.g., Coca-Cola and McDonald’s). Driven by globalization and the highly competitive Chinese market, an increasing number of FBs are reinventing their cultural mixing strategies. For instance, luxury brands that lean toward their brand heritage with a sense of authenticity and tradition can incorporate some localized elements into their product designs based on the consuming country while preserving their global heritage style (e.g., Dior incorporates Chinese floral art patterns into their iconic botanical heritage design style; Gucci created the “Shanghai Dragon Boston Bag,” whose design was inspired by the ancient Chinese symbol of the dragon as a sign of good luck to commemorate the opening of its 28th store in Shanghai China). However, some efforts by FBs to incorporate Chinese elements resulted in negative responses (e.g., the dragon-themed swimsuit of Victoria’s Secret, which gained negative feedback from social media netizen fans due to an inappropriate connection between the sacred dragon and lingerie).

Hong et al. (2000) explain that the study of cultural mixing is derived from the concept of polyculture psychology, which develops hybrid cultures from various cultural elements. This perception complements multicultural psychology and strengthens the views of cultural and cross-cultural psychology that cultures are static and independent and that individuals unconsciously internalize them. Research has explored new cultural frames that treat culture as evolving, changing, and interacting (Morris et al., 2015).

Cui et al. (2016) introduced two types of culturally mixed framing strategies for evaluating CMPs based on Costello and Keane’s (2001) psycholinguistics conceptual combinations of “noun-noun” that define the relationship between CMP different properties. The “noun-noun” combination is composed of two parts: the modifier, known as the first noun in the phrase, and the head, known as the second noun in the phrase. The first combination, “foreign × host culture” framing, highlights that the foreign culture element is considered a modifier. Host culture symbols are presented in the head category, implying that the attributes of the modifier (foreign culture) can be transferred to the head category (host culture). For example, the CMP of “zongzi” rice dumplings (People all over China celebrate the traditional dragon boat race and eat rice dumplings, a practice that can be traced back to 278 BCE) and Frappuccino (a famous Starbucks ice coffee drink that has existed since 1995). For the “foreign × host culture” framing, “Frappuccino dumpling” indicates that the culturally mixed product is a Chinese culture mix with some elements of American culture.

The second framing is the “host × foreign culture,” which describes the host culture element as the modifier and the foreign culture elements as the head that changes the host culture. For example, the “host × foreign culture” construct, such as Pizza Hut’s “Peking duck pizza,” embodies an American cultural element that integrates some aspects of Chinese culture instead. Peking duck has been one of the most symbolic Chinese dishes since the Imperial era. Therefore, the head brand is considered a subtype due to the influence of the modifier brand. These cultural structures can coexist simultaneously within the same product, thereby extending interdependence, interconnectedness, and interculturality (Chiu et al., 2009).

FBs must strategically figure out how consumers in a host country recognize the co-existence of cultural brand elements in co-branding (e.g., from West to East, or vice versa). Co-branding partners simultaneously incorporate the aspects of distinct cultures to create CMCPs. More importantly, a co-branding strategy avoids drawing host country consumers’ concern about the typical images of Western and Eastern cultures by simultaneously presenting two cultures in one product, which can improve consumer evaluation and the concept of congruity (He and Wang, 2017). There is a probability that a high degree of perceived fit between local cultural elements and FB images helps reduce cultural sensitivity and leads to positive consumer integrative responses. Therefore, this study focuses on the FB × PB and PB × FB co-branding strategies that produce CMCPs.

Congruity theory—the role of perceived fit and cultural congruence in co-branding

One way of conceptualizing co-branding partnerships is through congruity or fit. Congruity theory proposes that consumers seek a consistent balance, fit, and association between brand and product concepts (Turan, 2021). Perceived fit is the psychological congruence between two product categories or brands, which significantly determines co-branding success or failure (Mitchell and Balabanis, 2021). It plays a significant role in choosing the best brand with which to partner in co-branding alliances.

Simonin and Ruth (1998) classified the perceived fit of brand alliances into product and brand fit. Product fit refers to the degree of the perceived relatedness between two or more product categories. For example, Burberry collaborated with the famous Chinese video game “Honor of Kings” to outfit game characters with accessories such as Burberry’s signature trench coat and tartan, which was only available to players in China and reached more than 100 million average daily users.

In contrast, brand fit measures the degree of consistency between the brand images of two brands. A poor brand fit for a co-branded product may result in undesirable associations in consumers’ minds. For example, when a local brand, HEYTEA (a PB selling milk tea), collaborated with Durex (a condom brand), it faced substantial public backlash as consumers found it odd to connect tea and sex. Thus, poor brand fit can significantly affect consumers’ attitudes toward a co-branded product and behavioral intentions (Helmig et al., 2007). In contrast, a positive perceived fit creates a synergy that allows each brand to leverage its strengths. Additionally, we assume that a greater perceived fit will yield a higher effect for FBs’ co-branding with PBs because FBs are considered global players whose products are marketed in multiple countries. FBs know how to create powerful synergies by using their strengths and forming alliances with unknown or known PBs that are sensitive to local tastes, which can compensate for FBs’ weaknesses in the host country. Therefore, we propose the following hypotheses:

H1: Product fit’s influence on attitude toward CMCP of FB × PB is stronger than that of PB × FB.

H2: Brand fit’s influence on attitude toward CMCP of FB × PB is stronger than that of PB × FB.

Most studies on co-branding focus on product fit and brand fit, which lead to successful brand alliances. However, cultural congruence or brand identity fit between two partners significantly influences the direction and outcome of co-branding. Consequently, partnerships between companies from different countries may be problematic. For example, cooperation will prove difficult if FB’s culture is innovative and PB’s culture is conservative. Culturally congruent appeal conforms to prevailing cultural norms and values (Zhang and Gelb, 1996). Song et al. (2018) note that when an FB product contains cultural elements familiar to the product-consuming country (e.g., Kung Fu martial arts in the Kung Fu Panda movie for Chinese consumers), receivers positively evaluate and accept it. The brand’s cultural meaning also provides a storytelling approach for consumers to create an emotional attachment to the brand (Xiao and Lee, 2014). If both co-branding partners’ brands have congruent cultural associations, local consumers may perceive that they share similarities in culture, rituals, and spirituality, which facilitates long-term social relationships (Han et al., 2023). FBs are icons that create a global culture and give consumers a sense of belonging as global citizens (Zhang, 2010). They attract consumers due to their global values, traits, and practices. Unlike FBs, which show what we aspire to be, PBs demonstrate what we are, creating a world in which an individual consumer dreams of being a part of a whole. Thus, FBs that reflect host cultural elements are more persuasive than those that do not. Hence, we hypothesize the following:

H3: Cultural congruence’s influence on attitude toward the CMCP of FB × PB is stronger than that of PB × FB.

Cultural sensitivity in the form of cultural respect

Global brands wanting to expand and operate their businesses in foreign markets must have cultural sensitivity that aligns with their marketing strategies across cultural boundaries. Cultural sensitivity stems from Earley and Mosakowski’s (2004) conceptual framework of cultural intelligence, which encompasses cognitive, physical, and motivational components. Specifically, it refers to awareness, understanding, and embracing various actual cultural practices and cultural differences in the host nation’s market or those perceived by its host nation partner (Shapiro et al., 2008). For instance, to enter different markets, FBs must tap into local cultural sources through cultural respect (Guo et al., 2019) as an attribute of cultural sensitivity (Shapiro et al., 2008). Moreover, FBs that remain relevant to international customers must establish solid cultural connections with their host countries’ markets (Nie and Wang, 2019). It indicates that FBs, which are considered outsiders, must avoid undermining local traditions by showing sensitivity to local culture or facing consumer backlash.

For example, in Dolce and Gabbana’s (D&G) advertising campaign, a struggling Chinese fashion model eats Italian foods (e.g., pizza, cannoli, and pasta) with chopsticks. The D&G campaign received a dramatically negative reaction from Chinese citizens, and big e-commerce pulled the brand’s product from its platform due to its racist content, which disrespected Chinese culture. In addition to this challenge, many FBs are unsure what the globality of their brand culture means to their host country’s consumers or whether this global brand culture is an attribute that should be introduced or perhaps concealed in marketing activities as it may be interpreted as exhibiting a lack of sensitivity to other cultures. Based on previous studies, we assume that the “host × foreign culture” collaboration makes host country consumers positively evaluate the CMCP framework because the foreign country’s cultural attributes are perceived as only a subtype category. The CMCP of PB × FB indicates FBs’ cultural sensitivity to working according to the host country’s culture and is a sign of respect. Accordingly, we put forward the following hypothesis:

H4: The influence of attitude toward CMCP on the cultural sensitivity of PB × FB is stronger than that of FB × PB.

Product quality perception

Signaling theory considers consumer formation of quality perceptions through various signals, such as extrinsic cues (e.g., country of origin), as an important medium for assessing product quality (Javeed et al., 2022). If a country is associated with a brand or product, its image can influence consumer perceptions of product quality (Jin et al., 2020). Local consumers from non-Western countries often prefer Western FBs because these brands are perceived to have higher product quality (Batra et al., 2000). Mohan et al. (2018) assert that when an unknown local brand partners with a famous global brand, the latter will help signal a slight variance in consumers’ perceived product quality toward the unknown local brand, thus enhancing the brand evaluation. Collaborative brands capture the synergistic effect that affects consumer perceptions of the quality of a brand and its products, leading to the production of higher-value-branded products (Pinello et al., 2022). Co-branding enables consumers to avoid risks by signaling high-quality co-branded products, especially when compared with a single brand (Rao et al., 1999). In addition, FBs have advantages in terms of both intrinsic and extrinsic product quality attributes (Yu et al., 2022). Therefore, based on previous studies, we assume that FBs that collaborate with other local brands are perceived as having an overall global reputation and are of higher quality than local brands and propose the following:

H5: The influence of attitude toward CMCP on product quality perception of FB × PB is stronger than that of PB × FB.

Attitude and purchase probability

The theory of reasoned action suggests that consumers behave based on their pre-existing attitudes (Fishbein and Ajzen, 1975). The relationship between attitude and purchase intention is supported by previous studies (Suzuki and Kanno, 2022). Scholars have investigated why local consumers prefer FBs and how it affects their attitudes and purchase intentions (Batra et al., 2000). Drawing from previous studies focusing on local cultural capital, Steenkamp et al. (2003) found that the perception of local brands as icons of local culture directly impacts purchase probability. Özsomer and Altaras (2008) argued that through their in-depth understanding of local culture and the market, local brands can “out-localize” FBs in local markets because FBs are only regarded as symbols of cultural ideals. Moreover, Li et al. (2021) stated that consumers’ attitudes toward local brands with patriotic images enhance their purchasing intention due to their sense of psychological ownership of the local brand. Therefore, based on previous findings, we hypothesize:

H6: The influence of attitude toward CMCP on the purchase probability of PB × FB is stronger than that of FB × PB.

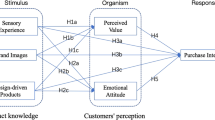

We formulated a conceptual model based on these hypotheses, as shown in Fig. 1.

Research method

Brand and product selection

During the preparation stage for selecting the brands and products to be examined, 216 Chinese undergraduate students from a Sino-foreign university in China participated in an experiment in exchange for course credit. The respondents were generally familiar with FBs and were knowledgeable about their home country brands.

To investigate the proposed conceptual model, we examined genuine brands to determine whether a co-branding strategy could stimulate real brand effects and connections (Simonin and Ruth, 1998). We specifically employed popular Chinese beverage brands that actively engaged in co-branding strategies and recognized the distinct variance in the explanatory constructs.

In Step 1, following Yu et al.’s (2021) research approach to co-branding, this study selected eight popular beverage FBs: Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Starbucks, Red Bull, Sprite, 7-Up, McCafé, and Costa Coffee, and five popular beverage PBs: Cha Yan Yue Se [茶颜悦色], Nayuki’s Tea [奈雪的茶], LeLeCha [乐乐茶], Jianlibao [健力宝集团], and HEYTEA [喜茶]) as the consideration set in the Chinese market because they have crossover co-branding collaborations as a common marketing strategy. Student respondents (n = 35) were educated on co-branding, FBs, and PBs and were then asked to select the desired FB and PB to examine their associations with a co-branded product. Respondents mainly chose Starbucks (mean = 5.63, SD = 1.32) and HEYTEA (mean = 5.59, SD = 1.41) for the desired FB and PB, respectively, indicating the congruence of brand attitude for a good combination of co-branding partners (see Table 2).

In Step 2, different student respondents (n = 35) from Step 1 were selected through convenience sampling to understand the concept of CMCPs. They were asked to rate seven different co-branding product categories (i.e., tumblers, mugs, tea sets, key chains, postcards, and bags) that Starbucks and HEYTEA sell and can best represent CMCPs in the Chinese market. The “tea set” (mean = 6.10, SD = 1.36) received the most votes for CMCP. Feedback from the respondents that every family in China has at least one tea set that they use to offer tea to family members, guests, and friends as a symbol of affection, friendship, and love.

In Step 3, we obtained a number of American and Chinese cultural symbols from Minahan (2009a; 2009b) and King (2012). Initially, we individually listed five common American cultural symbols (e.g., Teddy bear, Eagle, Knight, Lion, and Castle) and five Chinese cultural symbols (e.g., Panda bear, Dragon, Tai Chi, Peony, and Tiger). A total of 38 student respondents (different from those in Steps 1 and 2) were recruited using a convenience sample and asked to evaluate the most representative American and Chinese cultural symbols. The participants indicated a high level of agreement that the teddy bear symbolized the culture of FBs (mean = 5.26, SD = 1.81) and the panda bear symbolized the culture of PBs (mean = 5.45, SD = 1.77). These two symbols were chosen as modifier categories for the CMCPs.

In Step 4, we designed two tea sets using the bicultural framing conditions of hybrid products (i.e., foreign × host culture and host × foreign culture). Figure 2 shows a Chinese tea set incorporating the features of an American teddy bear, “teddy bear in a Chinese tea set,” representing the concept of “foreign × host culture.” Figure 3 shows the “panda bear in an American tea set” as “host × foreign culture,” where an American tea set is depicted incorporating the features of a Chinese panda bear.

Finally, a brief introduction to the two types of CMCP paired with pictures was presented to new respondents (n = 108) selected by convenience sampling. They were asked to rate the degree to which they perceived CMCPs as culturally mixed using a 7-point Likert scale (1 = no cultural mixing, 7 = highest degree of cultural mixing). Table 3 summarizes the results for the “teddy bear in a Chinese tea set” (M = 5.21; t(107) = 36.32; p < 0.01) and “panda bear in American tea set” (M = 5.52; t(107) = 45.37; p < 0.01). An independent t-test for the two samples indicated no significant differences in participants’ preferences for bicultural products, t(214) = 1.62, p = 0.106.

Research sample

Data was collected during a 45-day period by a marketing agent in Shanghai, China, using an online questionnaire. As Chan et al. (2009) described, PBs are gaining ground in first-tier cities of China, such as Shanghai, which is considered the most cosmopolitan city in the country, and there is intense competition between FBs and PBs in the said target location.

The samples were evaluated using two CMCPs (i.e., FB × PB and PB × FB). A total of 547 respondents were collected in this study. However, some respondents were excluded because of low brand familiarity (i.e., Starbucks and HEYTEA) or incomplete questionnaires (n = 68). Thus, 479 valid surveys were obtained, comprising n = 231 (FB × PB) and n = 248 (PB × FB). According to Schumacker and Lomax’s (2004) research, the sample size per group satisfied minimum requirements. The demographic data showed that male respondents accounted for 53% of the sample. Regarding the respondents’ age, 44% were 25–35, followed by 18–24 (32%), 36–50 (21%), and 51 and above (3%). Furthermore, 63% of the respondents had a bachelor’s or graduate degree. Regarding income, 68% of the respondents had a monthly income of more than US $1,000, and more than half (52%) had a habit of purchasing milk tea, coffee, or other beverages at least three times a week.

Measurements

Table 4 shows multi-item scales of nine constructs based on previous literature. A 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) was adopted to measure each item. Each question was assessed using back translation (e.g., English to Chinese and vice versa) to achieve meaning equivalence or similarity in both languages (Brislin, 1970). A factor analysis revealed that all data passed the standard requirements of Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) (>0.7) and Bartlett’s test (p < 0.01). Furthermore, all standardized factor loadings were >0.5 (Hair et al., 1998), the coefficients of composite reliability (CR) were >0.7, the coefficients of average variance extracted (AVE) were >0.5 (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1994), and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were >0.7 (Bagozzi and Yi, 1988). Finally, Table 5 shows that the square roots of all AVE coefficients were greater than the correlation coefficients of all constructs (Fornell and Larcker, 1981).

We implemented the following steps to avoid common method variance (CMV) in this study. First, the survey items were randomly assigned to an online questionnaire. Second, based on the Harman one-factor test, we used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to determine whether a single factor explained <50% of the total item variance (Malhotra et al., 2006). The eigenvalues of all the factors for both FB × PB and PB × FB datasets were >1. The items were calculated using a single factor, explaining 37% (FB × PB) and 32% (PB × FB) of the variance. Thus, CMV was not significant in this study.

Results

As shown in Fig. 1, AMOS was employed to perform a multi-group path analysis (FB × PB and PB × FB) to evaluate the conceptual model. The model fit statistics showed adequate fit (χ2 = 61.215, df = 24, p < 0.01, RMSEA = 0.057, AGFI = 0.916, CFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.911, SRMR = 0.072). Due to the influence of sample size on the measurement model’s sensitivity, the significance of the χ2 index diminishes the degree of model fit. Therefore, decisions rely on other fit indices, as Byrne (1998) noted. Specifically, product fit had an effect on attitude toward co-branded products for FB × PB (β = 0.14, p < 0.05) and <PB × FB (β = 0.36, p < 0.01). Thus, H1 was not supported, while H2 was supported because of the effect of brand fit on attitude toward co-branded products for FB × PB (β = 0.41, p < 0.01) > PB × FB (β = 0.28, p < 0.05). In terms of the effect of cultural congruence on attitudes toward co-branded products, FB × PB (β = 0.35, p < 0.01) < PB × FB (β = 0.41, p < 0.01), indicating that H3 was not supported. Notably, H4, H5, and H6 were supported because the effects of attitude toward the co-branded products on cultural sensitivity for FB × PB (β = 0.09, p = 0.17) and PB × FB (β = 0.23, p < 0.01), on product quality for FB × PB (β = 0.39, p < 0.01) and PB × FB (β = 0.10, p = 0.11), and on purchase probability for FB × PB (β = 0.31, p < 0.01) < PB × FB (β = 0.49, p < 0.01), respectively. Table 6 summarizes the structural equation modeling results. Figures 4 and 5 show the two types of co-branding estimated models.

Discussion and conclusions

This study explored the simultaneous presentation of two cultures (American and Chinese) in the mixed cultural framing of co-branded products (foreign × host culture and host × foreign culture). Diverse studies on cultural mixing call for a more in-depth investigation of the nature of co-branding strategies.

First, concerning the fit perceptions of a co-branding strategy, the results show that the effects of product fit and brand fit on co-branding attitudes by FB × PB (“foreign × host culture” framing) and PB × FB (“host × foreign culture” framing) are significant. The association between Starbucks and HEYTEA is that they share essential product attributes and demonstrate consumers’ familiarity with brands, which is derived from a match-up of brand image (Ho et al., 2017). Second, regarding product fit, Chinese consumers prefer the PB × FB culturally mixed co-branding strategy to the FB × PB counterpart. Host country consumers expect products to carry typical cultural values and symbols that affirm their cultural identity (Nie and Wang, 2019). Moreover, the influence of brand fit on the attitude toward co-branded products of FB × PB was stronger than that of PB × FB. Chinese consumers consider FBs a critical and positive brand reputation signal for heuristic decision-making, which reduces information asymmetry or the risks associated with purchases. As Simonin and Ruth (1998) demonstrated, well-known FBs (e.g., Starbucks) are important in enhancing the anticipated value of CMCPs.

Third, both culturally mixed co-branding framing strategies show a significant degree of cultural congruence of American elements in PBs and vice versa, which suggests consumers have a profound comprehension of the cultural symbols of both brands in the host country. The findings of this study contradict those of Yang et al. (2016), who argued that the co-presence of local cultural symbols or icons with FBs’ cultures evokes negative responses to culturally mixed products. The findings of the present study show that PB × FB is stronger than FB × PB, which implies that culturally mixed framing strategies are congruent with the host culture and the overall cultural proximity between the FB’s country and consumers in the host country (Song et al., 2018), rewarding co-branding brands that understand the culture and tailoring products to reflect its values.

Fourth, Chinese consumers recognize the cultural sensitivity of PB × FB relative to FB × PB. This finding shows that FBs that embrace Chinese cultural elements (e.g., the panda bear) in their products make glocalization efforts to be culturally respectful by attaching importance to other cultures. Guo et al. (2019) assert that CMPs, a respectful way of embodying local symbols, are essential for FBs as they provide a local foundation for their products. This may indicate that the cultural attributes of PBs’ transmission to FBs lead to new cultural perceptions in the host country, thus changing FBs’ identities. Hence, host consumers perceive less cultural intrusion or are less culturally threatened by FBs. Notably, FBs play a key role in facilitating mutual accommodation and reciprocal respect for the host country, which tends to view the FB culture as a resource that complements the host country’s culture (Simon and Schaefer, 2018), eventually influencing consumer attitudes toward CMCPs.

Fifth, the product quality perception of FB × PB is stronger than that of PB × FB. The results show that the “foreign × host culture” (FB × PB) framing highlights consumers’ product quality perception. This result supports the conclusions of previous studies that consumers in developing countries, such as China, are more likely to prefer FBs because of their perceived higher product quality, even when local product’ quality is similar to or better than FBs, particularly when the quality of local brands is not yet salient (Batra et al., 2000; Balabanis and Diamantopoulos, 2016). Furthermore, FBs play a crucial role in the quality of co-branded products, likely owing to “foreign product bias” (Mueller et al., 2016).

We can also conclude that strong FBs, such as Starbucks, may improve the co-branding alliance with local brands, with Chinese consumers perceiving the co-branded products to be of higher quality. In addition, with recent technological advancements in China, the product quality of some PBs now rivals that of FBs (Yu et al., 2022). However, consumers who lack information on PB quality improvements may still base their decisions on existing stereotypes and believe that FBs have higher product quality. Regarding “host × foreign culture” (PB × FB), this study’s results support Guo et al.’s (2019) argument that this culturally mixed match is still imperfect as most PBs still need to catch up with FBs’ globalness quality.

Finally, the findings provide specific insights that FBs may profit more from the PB × FB co-branding strategy as “host × foreign culture” framing significantly influences purchase likelihood. With China’s growing economic development, there is a stronger consumer sense of pride and patriotism toward local products. Host country symbols in foreign products often signify a closer bond with the host culture, reducing consumers’ resistance to potential cultural threats from FBs (He and Wang, 2017). Hence, patriotism positively influences local consumers’ purchase probability (Steenkamp et al., 2003). However, considering the positive impact of “host × foreign culture” framing on purchase probability does not necessarily exclude the impact of “foreign × host culture” framing. Indeed, such culturally mixed framing still increases host country consumer sensitivity to the prototypic attributes of the FB culture that PBs embrace in their product designs (Chiu et al., 2009).

Theoretical implications

Our findings contribute to the academic literature. First, our study contributes to a better understanding of FBs’ glocalization strategies (Liu et al., 2019). Given Chinese consumers’ growing power and the Chinese market’s distinct nature, many FBs are forced to compete with national brands by “clothing their wolf products in sheep’s clothing” (Belk, 2000, p. 68). Our study focuses on product glocalization; while FBs retain recognizable brand elements, they can incorporate Chinese styles into their product conceptualizations to cater to host country consumers and innovate, illustrating how intimately FBs’ consumers perceive FBs’ product glocalization and the relevance of making FBs local. Through product glocalization, this study introduces the concept of Guochao in the Chinese market, wherein local brands attempt to project themselves as sources of cultural pride and inspirational heroes. Thus, it adds specific insights that complement the growing number of studies showing that many consumers in host countries prefer FBs to identify with local attitudes, behaviors, lifestyles, and values to enhance local consumers’ purchase intentions (Sichtmann et al., 2018). Second, this paper highlights how modern China employs patriotism and continues to uphold its national identity with a slight shift from “made in China” to “designed in China.” The symbolic value of a product has connotations that represent a culturally specific local flavor or character that is jointly created by producers and consumers. Chinese brands that instill Guochao designs have already been established (e.g., sports brands Lining and HEYTEA, which have traditional Chinese features) and have a long history in China. However, the nationalization of product designs is still in its infancy; thus, it is essential to raise nationalized consumption to highlight “Chineseness” and seek cultural originality in a contemporary context. Notably, this study shows that the CMCP strategy is effective for shaping product glocalization, and Guochao was found to facilitate it.

Third, we contribute to a better understanding of cultural mixing theory (e.g., Chiu et al., 2009; Cui et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2019; Nie and Wang, 2019) in marketing and psychology, which suggests consumers react positively to bicultural elements or the hybridization of co-branded products. The findings of this study concerning CMCPs have valuable theoretical implications that allow us to evaluate the two rival sets of ideologies and reconfigure local cultural symbols (e.g., Guochao elements) to justify selling goods in the local market. This study also provides cultural insights into transitioning Chinese markets impacted by the tension between patriotism and globalization and consumers’ evaluations of FBs in the local market.

Fourth, this study acknowledges that the congruity theory, such as the perceived product fit, brand fit, and cultural congruence of CMCPs, enhances Chinese consumers’ symbolic significance and may result in desirable attitudes toward co-branding strategies that contribute to consumers’ integrative product perceptions of CMCPs. Co-branding partners should closely evaluate perceived fit because it is critical to collaborative success (Ho et al., 2017).

Fifth, the findings show that whether the collaboration is from FB × PB or PB × FB, Chinese consumers have positive attitudes regarding perceived fit and product quality, which contradicts Cui et al.’s (2016) findings that the framing strategy “foreign × host culture” resulted in a negative assessment of culturally mixed products. Here, we argue that this conclusion is not generalized because, in this study, Chinese consumers have a more favorable product fit attitude when the CMCP is “Chinese-culture × Western-culture” (i.e., HEYTEA × Starbucks tea sets) framing in which Chinese elements serve as the modifier category while the elements from a foreign culture occupy the head category.

Sixth, this study supports Shapiro et al.’s (2008) study on the importance of cultural sensitivity in glocalization strategy. FBs can navigate lucrative host country markets more adeptly. Also supports Rao et al.’s (1999) argument that brand collaborations are signals of product quality and that consumers in an emerging market may judge the quality of FBs to be of higher quality. From a signaling theory perspective, PB products have recently improved in terms of design and quality. Therefore, FBs paired with PBs may offer promising, quality products and help establish product positioning in the local market. In addition, when FBs partner with well-known PBs, the positive spillover effects of the PBs’ brand reputations can help them secure a high-quality CMCP.

Finally, several scholars (e.g., Li et al., 2021) documented rising patriotism among Chinese consumers; however, prior research has revealed that it seems paradoxical to understand Chinese consumers’ traits in the context of capitalist consumption. Given the findings of this study, we assume that Chinese consumers want to protect their local brands or cultures from being altered by foreign cultures. In this respect, Guochao or PBs’ co-branding strategies with FBs have increasingly satisfied Chinese consumers, both emotionally and socially.

Managerial implications

Despite increasing studies on whether the enormous Chinese market with 1.4 billion consumers prefers foreign and/or local products, FBs have conventionally incorporated Chinese cultural elements into their marketing practices in association with the Chinese market (He and Wang, 2017). Thus, there is a need for a more profound understanding of the cultural mixing between foreign products and patriotic Chinese brands through co-branding, which influences Chinese consumers’ purchase probability. Owing to the current incidence of consumer boycotts of FBs, multinational companies have started to become aware of Chinese cultural nuances and how best to traverse the complex waters of cultural differences between East and West. However, many FBs have difficulty determining how to implement local cultural symbolism because their understanding is only at the surface level, which, in turn, makes it difficult for host country customers to perceive their products or marketing strategies as sensitive or respectful. For instance, some FBs exploit the dragon symbol and the Chinese character 福 [fu], symbolizing “good fortune” in Chinese, without knowing if it matches.

Additionally, conflicts emerge when the degree of culturally congruent appeal between the brands and products is low. Some FBs have suffered Chinese consumers’ condemnation due to misrepresenting the host country’s culture in their products. Hence, anti-consumerist expressions toward FBs are growing louder on social media (e.g., Weibo and WeChat) regarding cultural insensitivity to local cultures in China. Notable examples include the Balenciaga Chinese Valentine hourglass handbags; the Adidas “Double Happiness” shoes; the Burberry scarf embroidered with the Chinese character 福 [fu], meaning “luck”; the Johnnie Walker Blue Label whisky bottle with the Chinese painting of the Three Rams from the Qing dynasty; and Kate Spade’s Chinese takeaway bags. Many companies fail to convey to consumers that a product is high-quality (e.g., local consumers may think it is a knockoff product sold in China’s low-end wholesale market) or effectively communicate a deep respect for understanding local cultural resources (e.g., local consumers may perceive as a marketing tactic). Therefore, FBs need a good understanding of how to blend cultural mixing into brand collaboration appropriately.

This study provides practical insights for FB managers as they attempt to tap into host countries’ cultural resources. Our findings show that despite the backlash faced by FBs in China, local consumers’ attitudes toward FB × PB and PB × FB collaborations are positive and represent a good match in product fit, brand fit, and cultural congruence. CMCP appears to be a sustainable win-win strategy in which two or more cultural elements coexist for both brands to gain positive consumer responses and for FBs to overcome cultural barriers and elevate their image to better blend with domestic consumers. For example, FBs’ CMCP efforts with PBs, such as Guochao brands, may capture Chinese consumers’ hearts and reshape their relationships with them.

Thus, West-East or East-West crossover could be an attractive way to elicit a positive assessment from both parties. For example, FB, as the co-branding initiator (i.e., FB × PB), is expected by host country consumers to produce quality products, whereas if a PB serves as the co-branding initiator (i.e., PB × FB), FBs are encouraged to show cultural sensitivity in a sincere manner. Therefore, practical implications for managers of FBs can be drawn from the following aspects. First, in brand collaboration, FBs can adopt CMCP to a higher degree without creating negative connotations, global and local hostility, or cultural conflicts. Second, it is crucial to continuously identify proper product fit, brand fit, and cultural congruence when incorporating host country elements into brand collaboration before and after implementing this strategy. Third, FBs must recognize that their globalness can enhance their attempts to tap emerging markets and local cultural resources. Managers should utilize different cultural mixed framing strategies to target different consumer segments. For example, FB × PB CMCP targets consumers with a strong global identity who display openness to foreign cultural elements depicted in a global product, while PB × FB CMCP targets consumers who strongly endorse conservatism characterized by PBs. Fourth, FB managers are reminded to continuously convey to host country consumers that the CMCP seeks to establish connections between different cultures in order to encourage an open attitude toward FBs utilizing local cultural resources. Finally, FBs are encouraged to embed patriotic themes in their branding and design of products, packaging, and marketing practices to increase local consumers’ favorable acceptance and purchase probability.

Limitations and future research

Although it makes significant theoretical and practical contributions, this research has several limitations. First, it focuses only on understanding Chinese consumer evaluations of CMCPs. We encourage scholars to explore this phenomenon through cross-cultural studies in other emerging markets. Second, our sample was from Shanghai, which limits the generalizability of the results to other cities in China. Significant differences exist among the different tier cities in China, presenting varied market environments. Third, this study only examined a non-food product category; therefore, further research could examine a greater variety of product categories and cultural elements and their effects on different evaluation outcomes (Guo et al., 2019). Future research may consider other consumer traits (Turan, 2021) and psychosocial factors in the model, such as consumers’ ethnocentrism (Tsai et al., 2013), consumer global identification (Magnusson et al., 2015), and consumer national identification (Dong and Tian, 2009), in the product positioning of co-branding products. Given that the understanding of consumer reactions to this phenomenon is limited, scholars studying co-branding should continue to explore and expand the conceptualization of glocalization strategies to determine their role in local markets.

Data availability

According to the confidential agreements with the participants, the datasets analyzed during the current study are not publicly available. We promised to keep the participants’ information confidential because they are frequent customers of the target shops of the study to encourage honest responses. However, the dataset can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Bagozzi RP, Yi Y (1988) On the evaluation of structural equation models. J Acad Mark Sci 16(1):74–94

Balabanis G, Diamantopoulos A (2016) Consumer xenocentrism as determinant of foreign product preference: a system justification perspective. J Int Mark 24(3):58–77

Balabanis G, Diamantopoulos A, Mueller RD, Melewar TC (2001) The impact of nationalism, patriotism and internationalism on consumer ethnocentric tendencies. J Int Bus Stud 32(1):157–175

Batra R, Ramaswamy V, Alden D, Steenkamp JB, Ramachander S (2000) Effects of brand local and nonlocal origin on consumer attitudes in developing countries. J Con Psych 9(2):83–95

Belk R (2000) Wolf Brands in Sheep’s Clothing: Global Appropriation of the Local. In Brand New edited by J Pavitt. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ. pp. 68–69

Brislin RW (1970) Back-Translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psych 1(3):185–216

Brown C (2022) These are America’s 50 most patriotic brands in 2023. Entrepreneur. https://www.entrepreneur.com/business-news/july-4th-clothing-see-americas-50-most-patriotic-brands/430385 Accessed 17 Nov 2022

Byrne BM (1998) Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS, and SIMPLIS: basic concepts, applications, and programming. Psychology Press

Carvalho SW, Luna D, Goldsmith E (2019) The role of national identity in consumption: an integrative framework. J Bus Res 103:310–318

Chan TS, Cui G, Zhou N (2009) Competition between foreign and domestic brands: a study of consumer purchases in China. J Glob Mark 22(3):181–197

Chen X, Leung AKY, Yang DYJ, Chiu C-Y, Li Z-Q, Cheng SYY (2016) Cultural threats in culturally mixed encounters hamper creative performance for individuals with lower openness to experience. J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1321–1334

Cheon BK, Christopoulos GI, Hong Y-Y (2016) Disgust associated with culture mixing: why and who? J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1268–1285

Chiu C, Mallorie L, Hean TK, Law W (2009) Perceptions of culture in multicultural space. J Cross-Cult Psych 40(2):282–300

Costello FJ, Keane MT (2001) Testing two theories of conceptual combination: alignment versus diagnosticity in the comprehension and production of combined concepts. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn 27:255–271

Craig CS, Greene W, Douglas S (2005) Culture matters: consumer acceptance of U.S. films in foreign markets. J Int Mark 13(4):80–103

Cui N, Xu L, Wang T, Qualls W, Hu Y (2016) How does framing strategy affect evaluation of culturally mixed products? The self–other asymmetry effect. J Cross-Cult Psych 47(10):1307–1320

Daxue Consulting (2021) Guochao marketing: in-depth interviews with Chinese Gen-Z. https://daxueconsulting.com/guochao-marketing/

Dong L, Tian K (2009) The use of western brands in asserting Chinese NATIONAL IDENTITY. J Con Res 36(3):504–523

Earley CP, Mosakowski E (2004) Cultural intelligence. Harv Bus Rev 82(10):139–146

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Fu JHY, Zhang Z-X, Li F-J, Leung YK (2016) Opening the mind: Effect of culture mixing on acceptance of organizational change. J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1361–1372

Gerth K (2008) Consumption and politics in twentieth-century China. In: Soper K, Trentmann F (eds.). Citizenship and consumption. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 34–50

Guo X, Heinberg M, Zou S (2019) Enhancing consumer attitude toward culturally mixed symbolic products from foreign global brands in an emerging-market setting: the role of cultural respect. J Int Mark 27(3):79–97

Hair J, Anderson R, Tatham R, Black W (1998) Multivariate data analysis. (5th edn.). Prentice Hall, New Jersey

Han J, Wang D, Yang Z (2023) Acting like an interpersonal relationship: Cobrand anthropomorphism increases product evaluation and purchase intention. J Bus Res 167:114194

He J, Wang CL (2017) How global brands incorporating local cultural elements increase consumer purchase likelihood. Int Mark Rev 34(4):463–479

Helmig B, Huber J-A, Leeflang P (2007) Explaining behavioural intentions toward co-branded products. J Mark Manag 23(3-4):285–304

Ho H-C, Lado N, Rivera-Torres P (2017) Detangling consumer attitudes to better explain co-branding success. J Prod Brand Manag 26(7):704–721

Holt DB (2004) How brands become icons: the principal of cultural branding. Harvard Business School Press

Hong YY, Morris MW, Chiu C-Y, Benet-Martinez V (2000) Multicultural minds: a dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition. Am Psychol 55:709–720

Javeed A, Aljuaid M, Khan Z, Mahmood Z, Shahid D (2022) Role of extrinsic cues in the formation of quality perceptions. Front Psychol 13:913836

Jin BE, Kim NL, Yang H, Jung M (2020) Effect of country image and materialism on the quality evaluation of Korean products. Asia Pac J Mark Log 32(2):386–405

Keh HT, Torelli CJ, Chiu C-Y, Hao J (2016) Integrative responses to culture mixing in brand name translations: the roles of product self-expressiveness and self-relevance of values among bicultural Chinese consumers. J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1345–1360

Kwan LYY, Li D (2016) The exception effect: How shopping experiences with local status brands shapes reactions to culture-mixed products. J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1373–1379

King G (2012) The history of the teddy bear: from wet and angry to soft and cuddly. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-history-of-the-teddy-bear-from-wet-and-angry-to-soft-and-cuddly-170275899/ Accessed 9 Oct 2022

Li Y, Teng W, Liao T-T, Lin TMY (2021) Exploration of patriotic brand image: its antecedents and impacts on purchase intentions. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 33(6):1455–1481

Liu SX (2016) Innovation design: Made in China 2025. Des Manag Rev 27(1):52–58

Liu Y, Tsai WS, Tao W (2019) The interplay between brand globalness and localness for iconic global and local brands in the transitioning Chinese market. J Int Cons Mark 32(2):128–145

Magnusson P, Westjohn SA, Zdravkovic S (2015) An examination of the interplay between corporate social responsibility, the brand’s home country, and consumer global identification. Int Mark Rev 32(6):663–685

Malhotra NK, Kim SS, Patil A (2006) Common method variance in IS research: a comparison of alternative approaches and a reanalysis of past research. Manag Sci 52(12):1865–1883

Minahan J (2009a) The complete guide to national symbols and emblems (Volume 1). Greenwood Publishing Group

Minahan J (2009b) The complete guide to national symbols and emblems (Volume 2). Greenwood Publishing Group

Mitchell VW, Balabanis G (2021) The role of brand strength, type, image and product-category fit in retail brand collaborations. J Retail Cons Serv 60:102445

Mohan M, Brown BP, Sichtmann C, Schoefer K (2018) Perceived globalness and localness in B2B brands: a co-branding perspective. Ind Mark Manag 72:59–70

Morris MW, Chiu C-Y, Liu Z (2015) Polycultural psychology. Annu Rev Psychol 66:631–659

Mueller RD, Wang GX, Liu G, Cui CC (2016) Consumer xenocentrism in China: an exploratory study. Asia Pac J Mark Log 28(1):73–91

Nie C, Wang T (2019) How global brands incorporate local cultural elements to improve brand evaluations. Int Mark Rev 38(1):163–183

Nunnally JC, Bernstein JH (1994) Psychometric Theory (3rd edn.). McGraw-Hill, New York, NY

Özsomer A (2012) The interplay between global and local brands: a closer look at perceived brand globalness and local iconness. J Int Mark 20(2):72–95

Özsomer A, Altaras S (2008) Global brand purchase likelihood: a critical synthesis and an integrated conceptual framework. J Int Mark 16(4):1–28

Passikoff R (2022) These are 2022’s most patriotic brands. Brand Keys. https://brandkeys.com/these-are-2022s-most-patriotic-brands/ Accessed 17 Nov 2022

Peng L-L, Tian X (2016) Making similarity versus difference comparison affects perceptions after bicultural exposure and consumer reactions to culturally mixed products. J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1380–1394

Pinello C, Picone PM, Mocciaro Li Destri A (2022) Co-branding research: where we are and where we could go from here. Eur J Mark 56(2):584–621

Rao AR, Qu L, Ruekert RW (1999) Signaling unobservable product quality through a brand ally. J Mark Res 36(2):258–268

Schumacker RE, Lomax RG (2004) A beginner’s guide to structural equation modeling. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Shapiro JM, Ozanne JL, Saatcioglu B (2008) An interpretive examination of the development of cultural sensitivity in international business. J Int Bus Stud 39(1):71–87

Shi Y, Shi J, Luo YLL, Cai H (2016) Understanding exclusionary reactions toward a foreign culture: the influence of intrusive cultural mixing on implicit intergroup bias. J Cross Cult Psychol 47(10):1335–1344

Sichtmann C, Davvetas V, Diamantopoulos A (2018) The relational value of perceived brand globalness and localness. J Bus Res 104:597–613

Simon B, Schaefer CD (2018) Muslims’ tolerance towards outgroups: longitudinal evidence for the role of respect. Brit J Soc Psych 57(1):240–249

Simonin BL, Ruth JA (1998) Is a company known by the company it keeps? Assessing the spillover effects of brand alliances on consumer brand attitudes. J Mark Res 35(1):30–42

Song R, Moon S, Chen H, Houston MB (2018) When marketing strategy meets culture: the role of culture in product evaluations. J Acad Mark Sci 46:384–402

Steenkamp JBE, Batra R, Alden DL (2003) How perceived brand globalness creates brand value. J Int Bus Stud 34(1):53–65

Suzuki S, Kanno S (2022) The role of brand coolness in the masstige co-branding of luxury and mass brands. J Bus Res 149:240–249

Torelli CJ, Chiu C-Y, Tam K-P, Au AKC, Keh HT (2011) Exclusionary reactions to foreign cultures: Effect of simultaneous exposure to cultures in globalized space. J Soc Issue 67(4):716–742

Tsai WS, Yoo JJ, Lee WN (2013) For love of country? Consumer ethnocentrism in China, South Korea, and the United States. J Glob Mark 26(2):98–114

Turan CP (2021) Success drivers of co‐branding: a meta‐analysis. Int J Con Stud 45(4):911–936

Xiao N, Lee SH (2014) Brand identity fit in co-branding the moderating role of C-B identification and consumer coping. Eur J Mark 48(7/8):1239–1254

Yang DYJ, Chen X, Xu J, Preston JL, Chiu CY (2016) Cultural symbolism and spatial separation: Some ways to deactivate exclusionary responses to culture mixing. J Cross-Cult Psych 47:1286–1293

Yu HY, Robinson GM, Lee D (2021) To partner or not? A study of co-branding partnership and consumers’ perceptions of symbolism and functionality toward co-branded sport products. Int J Sports Mark Spons 22(4):677–698

Yu SX, Zhou G, Huang J (2022) Buy domestic or foreign brands? The moderating roles of decision focus and product quality. Asia Pac J Mark Log 34(4):843–861

Zhang J (2010) The persuasiveness of individualistic and collectivistic advertising appeals among Chinese generation-X consumers. J Advert 39(3):69–80

Zhang Y, Gelb BD (1996) Matching advertising appeals to culture: the influence of products’ use conditions. J Advert 25(3):29–46

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Office of Research and Sponsored Programs, Wenzhou-Kean University, grant number WKUSSPF202202.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CLC: conceptualization, supervision, writing, reviewing, editing, project administration, and writing the original draft. HCH: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, validation, and writing the original draft. ZX, QW, and YY: visualization, investigation, resources, and writing the original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and or publication of this article. This paper has not been published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Ethical approval

The research methodology employed in this article relied on a questionnaire associated with a low level of risk. All participants provided informed consent, willingly participated in the survey, and were compensated appropriately for their time and effort. All procedures performed in studies were following the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

The authors sought and got the consent of the participants to participate in the study, who agreed to provide data for data analysis for this study. The authors informed each respondent of their rights and to safeguard their personal information. Also, the authors assured them of anonymity and that their responses were solely for academic purposes.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chiu, C.L., Ho, HC., Xie, Z. et al. Culturally mixed co-branding product framing in China: the role of cultural sensitivity, product quality, and purchase probability. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 475 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02954-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02954-1