Abstract

Maternal health is a major public health tricky globally. Cesarean section delivery reduces morbidity and mortality when certain complications occur throughout pregnancy and labor. Cesarean section subjected to the availability and use of essential obstetric services in regional factors in Ethiopia. There was a scarcity of studies that assess the spatial distribution and associated factors of cesarean section. Consequently, this study aimed to assess the spatial variation of cesarean section and associated factors using mini EDHS 2019 national representative data. A community based cross-sectional study was conducted in Ethiopia from March to June 2019. A two-stage stratified sampling design was used to select participants. A Global Moran’s I and Getis-Ord Gi* statistic hotspot analysis was used to assess the spatial distribution. Kuldorff’s SaTScan was employed to determine the purely statistically significant spatial clusters. A multilevel binary logistic regression model fitted to identify factors. A total of 5753 mothers were included. More than one-fourth of mothers delivered through cesarean section at private health institutions and 54.74% were not educated. The proportion of cesarean section clustered geographically in Ethiopia and hotspot areas were observed in Addis Ababa, Oromia, Tigray, Derie Dewa, Amhara, and SNNR regions. Mothers’ age (AOR = 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12), mother’s had secondary education (AOR = 2.113, 95% CI 1.414, 3.157), mother’s higher education (2.646, 95% CI 1.724, 4.063), Muslim religion followers (AOR = 0.632, 95% CI 0.469, 0.852), poorer (AOR = 1.719, 95% CI 1.057, 2.795), middle wealth index (AOR = 1.769, 95% CI 1.073, 2.918), richer (AOR = 2.041, 95% CI 1.246, 3.344), richest (AOR = 3.510, 95% CI 2.197, 5.607), parity (AOR = 0.825, 95% CI 0.739, 0.921), and multiple pregnancies (AOR = 4.032, 95% CI 2.418, 6.723) were significant factors. Therefore, geographically targeted interventions are essential to reduce maternal and infant mortality with WHO recommendations for those Muslim, poorest and not educated mothers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cesarean section (CS) is a life-saving surgical procedure when certain complications occur throughout pregnancy and labor1. It is one of the most popular and preferred delivery methods worldwide2,3,4. CS improves outcomes for infants and/or mothers5. Underuse of cesarean delivery increases perinatal death and morbidity and should continue to be a top concern for global health6. Prolonged obstructed labor, uterine rupture, and obstetric fistula are some of the serious problems that can be avoided with a timely CS7.

Cesarean section is estimated to save 287,000 maternal deaths and 2.9 million newborns worldwide annually8. However, pregnancy and childbirth-related deaths and morbidity are prevalent in developing countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, there are around 303,000 maternal deaths annually9. However, Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3.1 aims to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030 and to have no country with MMR above 14010.

As a strategy to achieve this goal, a comprehensive emergency obstetric and newborn care program is put into place, which includes essential services for addressing direct obstetric complications. The components of emergency obstetric and newborn care consist of antibiotics, medications to assist with uterine contractions, seizure prevention drugs, manual placenta removal, removal of any remaining pregnancy tissue, assisted delivery, newborn resuscitation, CS, and blood transfusions11,12. Indeed, achieving quality and equality in the availability of emergency obstetric care services, including safe cesarean section (CS), is key to attaining SDG 313. Neonatal mortality declined from 39 deaths per 1000 live births in 2005 to 29 deaths per 1000 live births in 2016 before increasing to 33 deaths per 1000 births in 201914.

The provision of essential obstetric and newborn care by skilled attendants during pregnancy and childbirth can ensure good maternal and birth outcomes. Cesarean delivery serves as an indicator of the availability and use of obstetric services in these situations15. There is lack of access to skilled care and crucial interventions in many resource-poor settings. Poorer countries have a lower incidence due to limited access to the procedure, even when it is needed, which has consequent impacts on maternal and neonatal morbidity/mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) provides estimates of CS prevalence by continent, 36% in America, 23% in Europe, 9% in Asia, 4% in Africa16. In Ethiopia, institutional deliveries increased from 26% in 2016 to 48% in 2019, while home deliveries decreased from 73 to 51% over the same period14. On the other hand, only 5% of live births in the 5 years before the survey were delivered by C-section. The rate of CS increased slightly from 2% in 2016 to 5% in 201914,17,18.

CS delivery depends on the availability and use of essential obstetric services, even when there is demand. These services subjected from regional factors in Ethiopia. Studies revealed a connection between CS and individual and community factors such as the mothers’ age, residence, education status of mother, place of delivery, pregnancy type, parity, and Antenatal care8,17,19,20,21,22,23. There was a scarcity of studies that identified hot and cold spot areas of CS, and associated factors like religion, sex of household head, and wealth index using nationwide representative data. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the spatial distribution of the prevalence of CS and its associated factors by utilizing mini EDHS 2019 data.

Methods

Study design and settings

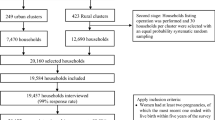

This study used community based cross-sectional study design, data obtained from the national Ethiopia mini Demographic and Health Survey (EMDHS 2019), which was implemented by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI) and Central Statistical Agency (CSA) under the auspices of the Ministry of Health. The survey was conducted from March to June 2019.

A two-stage stratified sampling design was used to select the households from a list of enumeration areas (EAs). A total of 645 clusters was selected in this survey at the first stage, which was considered as the primary sampling unit. Then, households were randomly selected using the systematic sampling method. The detailed procedure of sampling and study design well written in the report of this survey14. It provides data by urban and rural residents at the country level. The data used for CS estimation were extracted from the kid’s birth history section questionnaire which is included in the survey. For each birth, data were obtained within five years of the survey time.

Study variables

The dependent variable of this study was CS. A woman was considered to have a CS if her birth in the five years preceding the survey was via cesarean section.

Socio-demographic and obstetric characteristics and health-related variables were considered independent variables for this study. Level 1 (individual-level) variables include women’s age, education, religion, sex of household head, marital status, household wealth index, age at first childbirth, parity, Sex of child, multiple pregnancy, and place of delivery. Level 2 regions and residences were considered in the analysis.

Data management and analysis

The extracted data were analyzed using R version 4.2 to perform both descriptive and inferential analyses. Geographical information systems (Arc GIS) version 10.6.1 software was used for investigating spatial autocorrelation and detection of high and low-risk areas for CS. A spatial autocorrelation (Global Moran’s I) statistic measure was used to assess whether the practice is dispersed, clustered, or randomly distributed24,25. Moran’s I value close to −1 indicate a dispersed pattern, 0 indicate a random, pattern and close to a +1 indicates clustering of cesarean delivery practice in Ethiopia. A default inverse distance was used as a weight matrix to ensure that every cluster has at least one neighbor. The Getis-Ord Gi* hot spot analysis was used to identify spatial clusters of high values (hotspots) and spatial clusters of low values (cold spots). In this analysis, Z-score 1.96 and P value 0.05 were used as a threshold to determine the statistical significance of hot and cold spots clusters26,27.

The hotspot areas indicated that there is a high proportion of cesarean delivery and the cold spots indicated that there is a low proportion of cesarean delivery in the cluster. In the presence of clustering of cesarean delivery, a Bernoulli probability-based model of spatial scan statistics was employed using SaTScan (version 10.1.3) software (URL: https://www.satscan.org/download_satscan.html) to determine the purely statistically significant spatial clusters28. The scanning window that moves across the study area, in which mothers delivered by CS were considered cases and those with no caesarean delivery were considered non-cases (controls), was fitted to run the Bernoulli probability model. The number of cases in each location had a Bernoulli distribution, and the model required data for cases, controls, and geographic coordinates. The default maximum spatial cluster size of 50% of the population was used as an upper limit, which allows both small and large clusters to be detected and ignores clusters that contain more than the maximum limit. For each potential cluster, the likelihood ratio test statistic was used to determine if the observed caesarean delivery within the cluster was significantly higher than expected or not. The primary, secondary, and tertiary clusters were identified, assigned P-values, and ranked based on their likelihood ratio test, based on Monte Carlo replications29,30,31,32,33,34.

Due to the hierarchical nature of the mini EDHS data, mothers are nested in a cluster. As a result, mothers within a cluster have homogeneous and across a cluster they have heterogeneous characteristics. As a matter of fact, the inter cluster variation should consider in the model. In this regard, the intra-class correlation (ICC) was calculated to determine the between-cluster variation35. Individual and community variables were included. A multilevel binary logistic regression model was fitted to examine the relationship factor variables and the outcome variable. Simple and multiple binary logistic regression models were fitted, and all variables with a P-value less than or equal to 0.25 in the simple binary logistic model were a candidate of the multivariable model. Then four models comprising different explanatory variable were fitted sequentially. Model 1 without the predictor variable used to for comparison, Model 2 includes only community-level variables, Model 3 includes only individual-level variables, and Model 4 includes both individual and community-level factor. The fitness of the model was assessed through log likelihood ratio test and Akaike information criterion (AIC).

Finally, as adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) was reported in the multiple multilevel-logistic regression model and statistical significance was declared at P-value < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

The EDHS survey was conducted through the required ethical clearance procedures. The 2019 Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey (2019 EMDHS) obtained ethical approval from the Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute Review Board, the Ministry of Science and Technology, the CDC, and ICF International’s Institutional Review Board. Furthermore, written informed consent or assent was obtained from each participant or caregivers during data collection. This study was conducted in strict accordance with the ethical standards set forth in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. Permission to gain access to DHS data was obtained from the DHS data archivist through a reasonable online request using http://www.dhsprogram.com. In addition, the data were treated as confidential, and no attempt should be made to identify any household or individual respondent interviewed in the survey. Finally, the information retrieved was used only for statistical reporting and analysis of our registered research.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of mothers

A total of 5753 women who had a history of delivery were included in this study. Regardless of residence more than three fourth of the participants were rural dwellers. More than half of mothers did not attended formal education and Muslim followers, 3149 (54.74%) and 2974 (51.69%), respectively. Regardless of household, only 1055 (20.08%) were from female household heads and 1964 (34.14%) were from the poorest households (Table 1).

Obstetrics characteristics

The study revealed that 2969 (79.92%) of the children were male. Of these male children, 6% were delivered via CS. Only 24 (14.37%) mothers were delivered through CS out of 163 (2.83%) multiple pregnant mothers. Out of 309 (5.37%) mothers who give baby at private health institution, more than one fourth mother delivered through CS (Table 2). The average parity per a mother was 4.04 (95% CI 3.97–4.10). In addition, the average of a mother at first age birth was 18.61 (95% CI 18.50–18.70).

Prevalence of CS in Ethiopia

In this study, the prevalence of CS in Ethiopia was 6.07% (95% CI 5.45, 6.69). Of those women, 14.37 (85.63%) give multiple births (Table 2).

Spatial distribution of CS in Ethiopia

A total of 624 clusters were used to run the spatial analysis of CS in Ethiopia. Each point on the map relates to one enumeration area with the proportion of each CS in each cluster. The red points on the map indicate areas with high proportions while the green one indicates areas with the lowest proportion of CS in Ethiopia. Accordingly, high proportion of CS was observed in northern Ethiopia (Addis Ababa, Oromia, Tigray, Amhara and Afar regions), eastern Ethiopia (Dire Dewa, and Harari regions), and the SNNPR regions, ranging from 40.00 to 66.66%. However, there was a low prevalence of CS in the Somali, Gambila, and Beninshangul-Gumez regions, with an average of 0.09–0.38% (Fig. 1).

Spatial and incremental autocorrelation result of CS

In Ethiopia, there is a clustering of CS in certain geographical areas. According to the global Moran’s I value [0.748164, (Z-score value = 16.4378, P value < 0.001)], CS has a geographical pattern in Ethiopia; with a less than 1% likelihood that this clustered pattern could be the result of chance. The bright red and blue colors of the end tails indicated an increased significance level in the distribution nature of CS (Fig. 2).

Hotspot analysis (Getis-OrdGi statistic) result of CS

The Hotspot analysis using Getis-OrdGi statistics revealed that the hotspot areas (red-colors) of CS in Ethiopia were mainly observed in the Addis Ababa, Oromia, Tigray, Derie Dewa, Amhara and SNNR regions. However, clusters in other regions were insignificant (Fig. 3).

SaTScan spatial analysis result of CS delivery in Ethiopia

The SaTScan spatial analysis detected a total of 120 statistically significant clusters of CS in Ethiopia. The SaTScan result suggests that the CS percentage inside the circular window was higher than that outside the window. The most likely primary SaTScan clusters of CS observed in the Amhara and Tigray region (coordinates = (8.651588 N, 39.118340 E)/65.24 km, RR = 4.89, P-value < 0.001). Mothers who have given birth in this spatial window had 4.89 times more likely risk of CS delivery compared to those mothers outside the spatial window. The most likely secondary SaTScan clusters were identified SNNP and Oromia region (coordinates = (9.585229 N, 41.849280 E)/3.57 km, RR = 4.94, P < 0.001). In addition, the third and fourth most probable clusters of CS were in Addis Ababa and Tigray regions, respectively (Table 3, Fig. 4).

Multilevel logistic analysis result for CS: model selection and random effect estimates

We computed four models from M1 to M4 as part of this study. The first was a null model, the second model included only random effects (region and residence), the third included solely individual factors, and the last included both individual and community factors. However, the variable sex of child and place of delivery were not a candidate of the multiple multilevel logistic regression model since their P-value greater than 0.25 in the simple multilevel binary logistic regression model. Random-effect results and estimation of model fitness of four regression models were presented here. The random estimations (regional effect: 0.7879; resident effect: 0.5375) of the model 2 suggest the presence of clustering variation in the outcome variable among administrative regions and residents. In Model 2, ICC values for level 2 and level 3 random intercepts were greater than 10, thus it can be said that CS among mothers varies among resident types and clusters within a region. Again, the AIC value for Model 4 was lower than that of other models. Hence, considering both ICC and AIC, we selected Model 4 as our final best model (Table 4).

Measures of association (fixed-effect) results

The mixed-effects regression model identified that mother’s age, mother’s educational status, religion, household wealth index, parity, and multiple pregnant were significant determinant of CS. When the age of the mother increases by one unit, the odds of CS delivery increase by 7% (AOR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02–1.12). The CS among mothers who had secondary education were 2.113 (AOR 2.113, 95% CI 1.414–3.157) times more likely practices than compared to uneducated mothers. Those mothers who had a tertiary education level were 2.646 times more likely to CS deliver as compared with counterpart of not educated mothers. Moreover, those mothers who follow Muslim religion were 36.80% smaller to CS as compared to Christian religion followers.

Furthermore, mothers from household’s wealth index of poorer, middle, richer and richest were more likely to CS delivery compared to mothers from poorest families. The study finds smaller odds of CS among mothers having multipara compared to primary, meaning that for one parity increase, the odds of CS delivery decreased by 17.5% (AOR 0.825, 95% CI 0.739–0.921). The likelihood of CS among mothers who were multiple pregnant were 4.032 (AOR 4.03, 95% CI 2.418–6.723) times compared to mothers singleton pregnant (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to estimate the spatial distribution of CS in Ethiopia and its associated factors. Maternal and child health is a global concern. Mode of delivery has a great role for both maternal and child health. The findings of this study revealed that the unweighted proportion of CS was 6.07% (95% CI 5.45, 6.69), it indicates that there is slight enhancement when this result compared with 2016 EDHS report which was 2%17,18. The possible difference could be related to the increment in the prevalence of institutional delivery from 26% in 2016 to 48% in 201914. As institutional delivery increased the signs of medical indications that lead to CS delivery are well known and mothers have a chance to prefer this type of delivery as a result this enhancement was observed.

Furthermore, the spatial analysis revealed that the prevalence of CS was clustered and it identified the hotspot and cold spot areas in Ethiopia. Consequently, hotspots of high CS proportion were observed in Addis Ababa, Oromia, Tigray, Derie Dewa, Amhara and SNNR regions. This finding supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia that revealed CS rate was high at urban centers36. The reason may be related with accessing healthcare facilities served cesarean section resulting high institutional delivery in these area as compared with the other regions37. Furthermore, most private and government hospitals concentrated in these administrative regions relative to others. However, clusters located in other regions were insignificant and the prevalence also low in Somali, Gambila, and Beninshangul-Gumez administrative regions. This could be related to the culture of mothers delivering at home and their followed religion38.

The finding of this study revealed that old aged mothers’ were more likely to CS delivery, this findings in line with studies39,40. This result probably related with the risk of delivery problems such as excessive bleeding during labor and prolonged labor are increased on old age mothers41. Moreover, pregnancy related complications like diabetes and hypertension are common at old age mothers42.

This study also indicated that mothers’ had secondary education were 2.113 times more likely to experienced CS compared to those who were not educated. Mothers who had tertiary and above education level were 2.646 times more likely to CS as compared to those not educated. This finding was in line with studies conducted in Ethiopia36,43,44. The possible explanation is higher educated mothers are more likely to seek health services like CS delivery and they have a chance to prefer CS. Moreover, those educated mothers have more knowledge towards the merit and side effect of CS delivery as compared to those not educated mothers45,46.

Muslim religion follower mothers were 36.80% less likely to deliver through CS as compared to Christian religion followers. This finding is in line with a study conducted in Ethiopia47. The possible reason might be Muslim follower m other’s needs to have more children since CS delivery decreases number of deliveries48,49. And also those mothers perceived as vaginal delivery is a natural way of delivery which allowed by Gods/religions so they are less likely to institutional delivery and elective CS47,50,51. This study also revealed those mothers who come from a poorer, middle, richer and richest household were more likely to deliver through CS than mothers from a poorest household. This finding was consistent with a study conducted in Ethiopia, which reported that the wealth index is significantly associated with CS36. Probably, mothers from these households are more intended to deliver at private health institution as compared to mothers from poorest since they able to pay for CS delivery service and the travel costs relatively22,47.

Moreover, mothers who had more parity were less likely to CS delivery, this finding was agreed with those studies conducted in Ethiopia36,52, India53 and Kenya54. The possible reason might be mothers who had multiparas are more experienced about labor which leads to decide vaginal deliver as compared to nulliparous mothers. Finally, multiple pregnant mothers were more likely to give birth via CS as compared to singleton pregnant mothers, which supported by studies conducted in Ethiopia52. Those multiple pregnant mothers more likely pregnancy related complications, fear labor, and physicians give special care for those mothers to reduce complications which are dangerous for both the mother and baby55,56. Based on the findings of this study, the government should give attention to the culture and religious barriers regarding the mode of delivery. Moreover, this study intended to recommend that the government should provide more a free service option for those poorest mothers having danger obstetric signs at any healthcare.

The main strength of this study was assessed geographical variation and using hierarchical multilevel model. The limitation of this study was cross-sectional design, which could not estimate any causal relation. Besides, there is the possibility of social desirability and recall biases from the respondents due to the nature of the study design. Furthermore, twin child are treated as different individuals and we used unweighted data.

Conclusion

This study revealed that the proportion of CS was geographically clustered in Ethiopia. This finding may inquire why these regions are cold spot so whether due to service inaccessibility or preference of mothers should be investigated in the future research. Furthermore, this study implies that policymakers and health professional should improve the awareness of Muslim, not educated, and poorest mothers regarding CS delivery and a free healthcare service.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Measure DHS website (http://www.measuredhs.com) but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with permission of Measure DHS.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CS:

-

Caesarean section

- EMDHS:

-

Ethiopia Mini Demography and Health Survey

- HH:

-

Household head

- MMR:

-

Maternal mortality rate

- MLE:

-

Maximum likelihood estimation

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Das, S. & Sahoo, H. Caesarean section delivery in India: Public and private dichotomy. Demogr. India 48, 36–48 (2019).

Sharifirad, G. H., Fathi, Z., Tirani, M. & Mehaki, B. Assessing of pregnant women toward vaginal delivery and cesarean section based on behavioral intention model. Ilam Univ. Med. Sci. 15, 19–23 (2007).

Bani, S., Seied, R. A., Shamsi, G. T., Ghojazadeh, M. & Hasanpoor, S. H. Delivery Agents Preferences Regarding Mode of Delivery for Themselves and Pregnant Women (Obstetrics, Gynecologists, Midwives) (2010).

Waniala, I. et al. Prevalence, indications, and community perceptions of caesarean section delivery in Ngora district, eastern Uganda. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2020, 5036260 (2020).

Moosavi, A. et al. Influencing factors in choosing delivery method: Iranian primiparous women’s perspective. Electron. Physician 9, 4150 (2017).

Betran, A. P. et al. Interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections in healthy women and babies. Lancet 392, 1358–1368 (2018).

Panti, A. A. et al. Perception and acceptability of pregnant women towards caesarean section in Nigeria. Age (Omaha) 20, 20–24 (2018).

Neuman, M. et al. Prevalence and determinants of caesarean section in private and public health facilities in underserved South Asian communities: Cross-sectional analysis of data from Bangladesh, India and Nepal. BMJ Open 4, e005982 (2014).

World Health Organization. Maternal mortality in 2005: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, and the World Bank (2007).

World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division (2019).

Otolorin, E., Gomez, P., Currie, S., Thapa, K. & Dao, B. Essential basic and emergency obstetric and newborn care: From education and training to service delivery and quality of care. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 130, S46–S53 (2015).

Jejaw, M., Debie, A., Yazachew, L. & Teshale, G. Comprehensive emergency management of obstetric and newborn care program implementation at University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia, 2021: An evaluation study. Reprod. Health 20, 76 (2023).

Waniala, I. et al. Prevalence, indications, and community perceptions of caesarean section delivery in Ngora District, Eastern Uganda: Mixed method study. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. 2020, 5036260 (2020).

EPHI, I. Ethiopian public health Institute (EPHI) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiop. Mini Demogr. Heal. Surv. 2019 Key Indic. (2019).

Shah, A. et al. Cesarean delivery outcomes from the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Africa. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 107, 191–197 (2009).

Soto-Vega, E. et al. Rising trends of cesarean section worldwide: A systematic review. Obstet. Gynecol. Int. J. 3, 73 (2015).

Mezemir, R., Olayemi, O. & Dessie, Y. Trend and associated factors of cesarean section rate in Ethiopia: Evidence from 2000–2019 Ethiopia demographic and health survey data. PLoS One 18, e0282951 (2023).

CSA, I. Central Statistical Agency (CSA) [Ethiopia] and ICF. Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey, Addis Ababa (Cent. Stat. Agency, 2016).

Adewuyi, E. O., Auta, A., Khanal, V., Tapshak, S. J. & Zhao, Y. Cesarean delivery in Nigeria: Prevalence and associated factors-a population-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 9, e027273 (2019).

Ahmmed, F., Manik, M. M. R. & Hossain, M. J. Caesarian section (CS) delivery in Bangladesh: A nationally representative cross-sectional study. PLoS One 16, e0254777 (2021).

Ajayi, K. V. et al. A multi-level analysis of prevalence and factors associated with caesarean section in Nigeria. PLoS Glob. Public Health 3, e0000688 (2023).

Tsegaye, H. et al. Prevalence and associated factors of caesarean section in Addis Ababa hospitals, Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 34, 136 (2019).

de Loenzien, M., Schantz, C., Luu, B. N. & Dumont, A. Magnitude and correlates of caesarean section in urban and rural areas: A multivariate study in Vietnam. PLoS One 14, e0213129 (2019).

Fotheringham, A. S., Brunsdon, C. & Charlton, M. Geographically Weighted Regression: The Analysis of Spatially Varying Relationships (Wiley, 2003).

Merlo, J. et al. A brief conceptual tutorial of multilevel analysis in social epidemiology: Using measures of clustering in multilevel logistic regression to investigate contextual phenomena. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60, 290–297 (2006).

Zulu, L. C., Kalipeni, E. & Johannes, E. Analyzing spatial clustering and the spatiotemporal nature and trends of HIV/AIDS prevalence using GIS: The case of Malawi, 1994–2010. BMC Infect. Dis. 14, 1–21 (2014).

Fischer, M. M. & Getis, A. Handbook of Applied Spatial Analysis: Software Tools, Methods and Applications (Springer, 2010).

Kulldorff, M. A spatial scan statistic. Commun. Stat. Methods 26, 1481–1496 (1997).

Ma, Y., Yin, F., Zhang, T., Zhou, X. A. & Li, X. Selection of the maximum spatial cluster size of the spatial scan statistic by using the maximum clustering set-proportion statistic. PLoS One 11, e0147918 (2016).

Kulldorff, M. SaTScanTM user guide (2018).

Kim, S. & Jung, I. Optimizing the maximum reported cluster size in the spatial scan statistic for ordinal data. PLoS One 12, e0182234 (2017).

Boscoe, F. P., McLaughlin, C., Schymura, M. J. & Kielb, C. L. Visualization of the spatial scan statistic using nested circles. Health Place 9, 273–277 (2003).

Besag, J. & Clifford, P. Generalized Monte Carlo significance tests. Biometrika 76, 633–642 (1989).

Gentle, J. E. Random Number Generation and Monte Carlo Methods Vol. 381 (Springer, 2003).

Weinmayr, G., Dreyhaupt, J., Jaensch, A., Forastiere, F. & Strachan, D. P. Multilevel regression modelling to investigate variation in disease prevalence across locations. Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 336–347 (2017).

Tegegne, T. K., Chojenta, C., Getachew, T., Smith, R. & Loxton, D. Spatial and hierarchical Bayesian analysis to identify factors associated with caesarean delivery use in Ethiopia: Evidence from national population and health facility data. PLoS One 17, e0277885 (2022).

Gilano, G., Hailegebreal, S. & Seboka, B. T. Determinants and spatial distribution of institutional delivery in Ethiopia: Evidence from Ethiopian Mini Demographic and Health Surveys 2019. Arch. Public Health 80, 1–12 (2022).

Hailegebreal, S., Gilano, G., Simegn, A. E. & Seboka, B. T. Spatial variation and determinant of home delivery in Ethiopia: Spatial and mixed effect multilevel analysis based on the Ethiopian mini demographic and health survey 2019. PLoS One 17, e0264824 (2022).

Abebe, F., Berhane, Y. & Girma, B. Factors associated with home delivery in Bahirdar, Ethiopia: A case control study. BMC Res. Notes 5, 653 (2012).

Azami-Aghdash, S., Ghojazadeh, M., Dehdilani, N. & Mohammadi, M. Prevalence and causes of cesarean section in Iran: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran. J. Public Health 43, 545 (2014).

Rydahl, E., Declercq, E., Juhl, M. & Maimburg, R. D. Cesarean section on a rise—Does advanced maternal age explain the increase? A population register-based study. PLoS One 14, e0210655 (2019).

Wang, Z., Yang, T. & Fu, H. Prevalence of diabetes and hypertension and their interaction effects on cardio-cerebrovascular diseases: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21, 1224 (2021).

Abebe, F. E., Gebeyehu, A. W., Kidane, A. N. & Eyassu, G. A. Factors leading to cesarean section delivery at Felegehiwot referral hospital, Northwest Ethiopia: A retrospective record review. Reprod. Health 13, 6 (2016).

Mekonnen, Z. A., Lerebo, W. T., Gebrehiwot, T. G. & Abadura, S. A. Multilevel analysis of individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery in Ethiopia. BMC Res. Notes 8, 376 (2015).

Logan, R. A. et al. Health literacy: A necessary element for achieving health equity. NAM Perspect. (2015).

Fesseha, N., Getachew, A., Hiluf, M., Gebrehiwot, Y. & Bailey, P. A national review of cesarean delivery in Ethiopia. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 115, 106–111 (2011).

Zewude, B., Siraw, G. & Adem, Y. The preferences of modes of child delivery and associated factors among pregnant women in Southern Ethiopia. Pragmat. Obstet. Res. 13, 59–73 (2022).

Gebre, M. N. Number of children ever-born and its associated factors among currently married Ethiopian women: Evidence from the 2019 EMDHS using negative binomial regression. BMC Womens Health 24, 95 (2024).

Ayele, D. G. Determinants of fertility in Ethiopia. Afr. Health Sci. 15, 546–551 (2015).

Tsehay, A. K., Tareke, M., Dellie, E. & Derressa, Y. Determinants of institutional delivery in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 8, 2187–2193 (2020).

Rahnama, P., Mohammadi, K. & Montazeri, A. Salient beliefs towards vaginal delivery in pregnant women: A qualitative study from Iran. Reprod. Health 13, 1–8 (2015).

Azene, A. G., Aragaw, A. M. & Birlie, M. G. Multilevel modelling of factors associated with caesarean section in Ethiopia: Community based cross sectional study. BMC Res. Notes 12, 1–7 (2019).

Shah, N., Maitra, N. & Pagi, S. L. Evaluating role of parity in progress of labour and its outcome using modified WHO partograph. Int. J. Reprod. Contracept. Obstet. Gynecol. 5, 860–863 (2016).

Van Der Spek, L. et al. Socioeconomic differences in caesarean section–are they explained by medical need? An analysis of patient record data of a large Kenyan hospital. Int. J. Equity Health 19, 1–14 (2020).

Schulze, G. & Radzuweit, H. Indication for caesarean section for multiple pregnancy (author’s transl). Zentralbl. Gynakol. 103, 347–354 (1981).

Jonsson, M. Induction of twin pregnancy and the risk of caesarean delivery: A cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15, 1–7 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the Measure Demographic and Health Survey for providing online permission to use the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2019 data set.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author AGA was responsible for the conception, formulation of the methodology, and analyzed. All authors made substantial contributions to the design of the study and interpreted the data. AGA was the main contributor in drafted and writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Azene, A.G., Wassie, G.T., Asmamaw, D.B. et al. Spatial distribution and associated factors of cesarean section in Ethiopia using mini EDHS 2019 data: a community based cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 14, 21637 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71293-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-71293-7

Keywords

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.