Abstract

This study aimed to develop the Global Assessment of Active Trolling and Passive Bystanderism (GAATPB) scale and investigate the influence of personality traits on trolling behaviors. Focusing on the Dark Tetrad (DT) traits and agreeableness, the present study examined their associations and predictive utility on active trolling and passive bystanderism. Participants were recruited from social networking sites (SNSs), and eligibility criteria included active SNS usage and engagement in online interactions. A total of 797 healthy adult students participated in the study, with data from 300 used for the initial exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the remaining 497 (Mage = 22.25 years, SD = 3.37) for the subsequent analyses. Results indicated a significant correlation between DT traits and agreeableness across both active trolling and passive bystanderism, revealing a shared personality profile. Hierarchical multiple regression analyses showed that narcissism, Machiavellianism, and trait sadism were predictors of active trolling, with psychopathy being the strongest predictor. However, psychopathy did not emerge as a predictor for passive bystanderism. The study also highlighted that DT traits mediated the relationship between lower agreeableness and overall trolling behavior, suggesting that trolling manifests from lower agreeableness through the instigation of callous-unemotional, manipulative, and self-centered traits inherent in DT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Internet trolling (or just trolling) is an antisocial online behavior, defined as a deliberate attempt to initiate unproductive and protracted discussions on social networking sites (SNSs) or discussion forums1,2. However, the terms ‘troll’ and ‘trolling’ can carry multiple, often inconsistent meanings, varying with the context of usage and the intentions of the user3,4. When used nominally, a troll identifies an individual who perpetrates such behavior. In its verbal form, the term draws a metaphorical parallel to a ‘fishing’ technique in which bait is dragged through the water to attract fish5. This analogy aptly captures the essence of trolling, where the perpetrator baits and provokes others in a digital environment. Trolls engage in aggressive online interactions, akin to cyberbullying and cyberstalking6, sometimes without full awareness of their target or the nature of their actions7. They often exploit anonymity to provoke conflict and demean others, making their targets appear foolish1,8. Common trolling behaviors include instigating contentious arguments, social manipulation, attention-seeking, and disseminating harmful messages1,3,5,9. These behaviors are often driven by motives such as boredom, attention-seeking, revenge, and communal animosity1,10. However, research indicates that trolling can also manifest in less malevolent forms11,12, suggesting a need to broaden the assessment and conceptualization of trolling as a multidimensional construct.

Early studies on trolling used qualitative methods, including in-depth interviews13 and content analysis of online posts5. Buckels et al.1 introduced the Global Assessment of Internet Trolling (GAIT), a four-item instrument designed to empirically evaluate trolling dimensions like experience, enjoyment, and self-identification. Later, Cracker and March9 developed the Global Assessment of Facebook Trolling (GAFT), a variant specifically adapted for the Facebook environment. Recognizing the content validity limitations of these scales, Sest and March14 proposed an improved version, the Revised Global Assessment of Internet Trolling (R-GAIT), which included additional items. Although studies affirm that internet trolling encompasses diverse behaviors and motivations5,15, the predominant focus has been on active interaction between the perpetrator and the victim, overlooking the role of bystanders.

Bystander behaviors manifest in online environments through a range of actions, from supporting the victim to remaining passive or even reinforcing the perpetrator16. Consequently, bystander intervention may assume both active and passive roles, exerting influences on the victim that can be either beneficial or detrimental. Positive bystander interventions, such as directly comforting victims, can mitigate the negative impact of online misconduct17. Similarly, actions such as reporting incidents to authorities, can reduce aggressive content and foster positive online social norms18. While positive bystander intervention can be beneficial, there is a notable tendency towards passivity during online misconduct19. Research suggests that sustained inactivity and a lack of empathy among passive bystanders may lead them to become active perpetrators20. The combination of passive bystander behavior and reinforcement of perpetrators can exacerbate online misconduct and amplify victim trauma21. This dynamic reflects patterns seen in traditional bullying, where bystander endorsement can escalate the aggressor’s actions22.

Bystander intervention in online misconduct is contingent upon the perceived sense of connection with the victim and personal safety23. A lack of such connection may lead to bystander passivity, which could potentially evolve into active aggression. The dynamics within SNSs further complicate this scenario. Users frequently encounter misconduct on these platforms beyond their immediate social circles, facilitated by features like ‘public content visibility’ and connections with ‘friends-of-friends.’ These features, along with the tendency of SNSs to foster ‘weak tie’ relationships, can contribute to a sense of anonymity, thereby diminishing the sense of connectedness crucial for effective bystander intervention24. The prevalent anonymity on the internet, especially in trolling scenarios1, underscores the need for a careful examination of passive bystander behaviors in these contexts. While passive bystander behaviors have been explored in other forms of online misconduct, such as cyberbullying and online hate23,25, there is a scarcity of studies addressing this issue in the context of internet trolling.

To address this research gap, the present study aims to develop the Global Assessment of Active Trolling and Passive Bystanderism (GAATPB) scale. This scale employs a two-dimensional framework to evaluate trolling behaviors, covering both active and passive bystander components. Active trolling is defined in its conventional form as intentional provocation or harassment conducted on SNSs1, characterized by deliberate actions intended to distress or provoke other users5. On the other hand, ‘passive bystanderism’ is examined, acknowledging its catalytic role in harming the victim and reinforcing trolls within online environments. The present study defines passive bystanderism as an act of observing or consuming provocative content on SNSs without directly participating in trolling activities or inflicting harm on the target. This passive engagement may include behaviors ranging from silently viewing and enjoying such interactions to subtly endorsing them. Furthermore, it examines the role of personality characteristics on the dimensions of trolling behavior, exploring the associations and predictive utility of dark personality traits and agreeableness on active trolling and passive bystanderism.

There has been a growing emphasis on exploring dark personalities and examining how these traits correlate with and influence trolling behavior. The Dark Triad is the most commonly used model to assess these malevolent traits, encompassing narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy26. However, the addition of trait sadism27 expands the framework to the Dark Tetrad (DT). Although these personality traits overlap and share characteristics like callousness, manipulation, and apathy27, they also exhibit distinctive attributes1. Narcissism involves grandiose self-perceptions about intelligence, power, and physical appeal28,29, whereas Machiavellianism is associated with deceptive behaviors and social manipulation30. Psychopathy is characterized by impulsivity and callous-unemotionality, indicated by a lack of empathy or guilt31. Trait sadism, closely related to psychopathy, involves deriving pleasure from others’ suffering32.

Individuals exhibiting high levels of Machiavellianism and narcissism engage in behaviors detrimental to others, primarily when it serves their self-interest and objectives33. Research has shown that both narcissism and Machiavellianism correlate positively with the enjoyment of trolling1. However, it is observed that when accounting for the shared variance among DT traits, neither narcissism nor Machiavellianism significantly predicts trolling behavior9,34,35. Reflecting on this, Craker and March9 suggested that individuals with high Machiavellianism may not favor the impulsive nature of trolling, preferring controlled and calculated approaches. They also speculate that highly narcissistic individuals, due to their self-absorption, may be less inclined to exert the effort required for aggressive trolling9.

Conversely, there is growing evidence that psychopathy and trait sadism have the most substantial predictive utility for trolling behavior1,9,14. Individuals exhibiting high levels of psychopathy are predisposed to behaviors that are impulsive, violent, and antisocial36. Pronounced psychopathy and sadistic traits are often associated with deriving pleasure from inflicting torment, with individuals displaying the willingness to undergo challenges in such conduct37. This propensity aligns with the behaviors of trolls who invest time and effort to anonymously disrupt and harm others on SNSs39,40.

In addition to the DT, the Big Five personality traits—openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism—have also been examined in the trolling literature. Studies have identified associations between trolling and some of these traits, such as higher levels of extraversion, reduced conscientiousness, and lower agreeableness1,34,38. However, except for lower agreeableness, these associations demonstrate variability and are not consistently reported across the literature39. Lower agreeableness (often conceptualized as antagonism) is characterized by tendencies toward meanness, inconsideration, and uncooperativeness, often resulting in deviant online interpersonal behaviors40. For instance, individuals with lower agreeableness are found to mock others, post harmful comments41, or even pursue vengeful actions on SNSs42. Such individuals often struggle to navigate hostility and disagreement in interpersonal interactions, primarily due to reduced empathy43. This propensity for less empathetic, hostile, and more antagonistic interactions can extend to online environments, particularly in situations that involve witnessing online misconduct. For instance, Zhou et al.44 reported that among the examined Big Five personality traits, lower agreeableness was the unique trait capable of simultaneously predicting both active participation in and bystander behavior within cyberbullying. However, to our knowledge, no study has yet explored the role of lower agreeableness in relation to passive bystander behavior in the context of internet trolling.

Considering its callous nature, there is an ongoing debate regarding whether lower agreeableness constitutes the common core of dark personalities or it diverges from them30,45, and whether this association can be extended to a causal relationship. Many studies underscore a substantial relationship between lower agreeableness with Dark Triad46,47 and DT traits48, suggesting a considerable overlap between these constructs. According to this line of argument, the commonalities among dark personalities may fundamentally reflect the opposing pole of the agreeableness dimension. For instance, lower agreeableness emerged as a fundamental component across the subscales of the Youth Psychopathic Traits Inventory (YPI)49. This tool encompassed ten scales organized into three first-order factors—Grandiose/Manipulative (G/M), Callous/Unemotional (C/U), and Impulsive/Irresponsible (I/I), collectively forming a second-order factor termed ‘psychopathic personality.’ Sherman et al.50 found that in a sample of college students, lower agreeableness accounted for over 55% of the variance in first-order factors and 45% of the variance in second-order factors of the YPI, underscoring its critical role in the structure of psychopathic personality. This trend extends to other dark personalities as well. For instance, the variance in narcissism attributable to lower agreeableness has been reported to range from 33%51 to 79%52. Similarly, this explained variance falls between 77%51 and 84%46 for Machiavellianism, as reported in the previous studies.

While acknowledging closer associations between these traits, it is critical to observe that the theoretical foundations of agreeableness and dark personalities fundamentally differ. Agreeableness is examined as a basic personality structure, derived from lexical studies to describe all major individual differences through as few independent dimensions as possible53. In contrast, dark personalities such as DT traits embody a confluence of various characteristics across basic personality dimensions. This perspective implies that the examined relationship between lower agreeableness and dark personalities could be causal, where lower agreeableness might predispose individuals to DT traits, rather than the other way around. Thus, lower agreeableness may not only be necessary but also sufficient for developing certain dark personality traits, making it an antecedent in the manifestation of their motives45,54.

Drawing upon the research findings discussed above, lower agreeableness and DT traits have been identified as significant predictors of active trolling. However, their association with bystander behaviors remains unexplored within the context of internet trolling. To bridge this research gap, the present study investigated the relationship and predictive utility of DT traits and lower agreeableness on the propensity for active trolling and passive bystanderism. Although the actions of perpetration and bystander intervention in online misconduct diverge, they both stem from a shared underlying motive of a lack of empathy14,55,56,57,58. Furthermore, considering that reduced empathy is also a characteristic associated with both DT traits59,60 and lower agreeableness61, it raises an intriguing question as to whether these traits differentially influence active trolling and passive bystanderism. To address this research question, the present study hypothesized that there would be no difference between active trolling and passive bystanderism in their relationship with the personality traits (hypothesis 1), the predictive utility of these traits (hypothesis 2), and the assumed mediation of DT traits in the relationship between lower agreeableness and these trolling dimensions (hypothesis 3). Expanding on these primary hypotheses, the study further explored the specific associations of DT traits and lower agreeableness on active trolling and passive bystanderism through additional sub-hypotheses.

Firstly, this study examined the relationship between personality traits and trolling dimensions. Drawing on previous studies1,9,14, it proposed a significant correlation between DT traits and agreeableness, with active trolling (hypothesis 1a) and passive bystanderism (hypothesis 1b). Subsequently, it examined the predictive utility of DT traits and agreeableness on both trolling dimensions. As discussed earlier, while narcissism and Machiavellianism are found to be significantly correlated with trolling behavior, their predictive utility has not been consistently reported1,34,39. Addressing this issue, the study hypothesized that in addition to agreeableness, only psychopathy and trait sadism would predict active trolling (hypothesis 2a) and passive bystanderism (hypothesis 2b). Furthermore, reflecting on the precursory role of lower agreeableness in fostering DT traits54, which in turn emerged as a predictor of trolling behaviors, it is hypothesized that DT traits would mediate the relationship between agreeableness and both active trolling (hypothesis 3a) and passive bystanderism (hypothesis 3b).

Methods

Participants

The study engaged a total of 797 adult participants who were recruited via advertisements on SNSs (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter). These advertisements contained a URL that directed potential participants to the online survey hosted on Google Forms.

Eligibility criteria included active use of at least one SNS and engagement in online social interactions, such as liking, commenting, and sharing content on these platforms. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was initially conducted with 300 participants to identify the dimensions of trolling behavior. Due to inadequate communality and lack of responses from the participants, an item was removed from the scale. A follow-up CFA was conducted with 497 participants (Males = 29.2%, Females = 69.21%; Mage = 22.25 years, SD = 3.37), and the same data was used for all subsequent analyses. Most participants identified Instagram as their preferred SNS for online activities (67.8%), followed by Facebook (10.8%). Prior to participation, written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Institute Human Ethics Committee of the authors’ affiliated institution, consistent with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Measures

Dark personality traits

The Dark Triad traits were assessed using the Dirty Dozen62, a 12-item self-report questionnaire. Participants indicated their level of agreement on a five-point scale (1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly) with statements targeting narcissism (e.g., “I tend to want others to admire me”), Machiavellianism (e.g., “I have used deceit or lied to get my way”), and psychopathy (e.g., “I tend to lack remorse”). The Dirty Dozen scale demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency on its subscales: Machiavellianism (Cronbach’s α = 0.80), narcissism (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), and psychopathy (Cronbach’s α = 0.75). Additionally, the Short Sadistic Impulse Scale63, comprising ten items, was employed to measure trait sadism (e.g., “people would like hurting others if they gave it a go”). The two scales were combined to yield an overall DT score (Cronbach’s α = 0.87).

Agreeableness

Agreeableness was measured using nine items from the Big Five Personality Inventory’s agreeableness domain64. Participants rated their agreement with statements (e.g., “I see myself as someone who is helpful and unselfish with others”) on a five-point scale (1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly). The scale exhibited satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

Trolling behavior

The investigators incorporated the items from GAIT1 and the R-GAIT14 scales to develop the proposed GAATPB. All four items were retained from the original GAIT scale, and one item was incorporated from the R-GAIT (“I enjoy upsetting people on Social Networking Sites”). The scale was adapted for the Indian context, replacing slang in the original items with language more culturally appropriate to the region. For instance, “I have sent people to shock websites for the lulz” was rephrased as “I have sent comments to people on social networking sites for fun.” Additionally, three new items were specifically developed by the researchers to measure passive bystanderism. Both population and expert sampling were employed for item generation65. Interviews with target population members and three subject experts ensured the representativeness of items to the passive bystanderism. Subsequently, the researchers consulted colleagues for final input and integrated their feedback before administering the measure. All items were specifically designed to evaluate trolling behaviors in the context of SNSs. The initial version of the scale comprised eight items, with responses recorded on a five-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly to 5 = agree strongly). However, an item was excluded following the initial EFA due to insufficient communality. Detailed descriptions of the development process of the GAATPB are further elaborated in the results section.

Data analysis

The present study utilized the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS®) Version 27 and Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) Version 22 to analyze the data. An EFA was conducted on the pilot study data (N = 300) to assess the factor structure of the measuring scale. Prior to item retention, standard assumptions of the EFA, including normality, sampling accuracy, sphericity, communality, and factor loadings, were verified. Should any items fail to meet these criteria, they were removed, and a further iteration of the EFA was performed on the same dataset. Missing data was replaced using multiple imputation method in the SPSS®. The EFA used principal axis factoring with a direct oblimin rotation to allow for the potential correlation between factors. Subsequently, a CFA was carried out on the field study data (N = 497) to validate the identified factor structure using the maximum likelihood estimation.

Further, a bivariate Pearson product-moment correlation and two-step hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted to examine the relationship and predictive utility of DT traits and agreeableness with active trolling and passive bystanderism. Standard assumptions were evaluated before running these tests. The first step of the regression analyses involved agreeableness as the predictor variable, followed by the introduction of DT traits. The predictors were entered in an order that aligned with the previous study66. Further, to examine the mediating role of DT in the relationship between agreeableness and trolling dimensions, a structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized, employing maximum likelihood estimation. Bootstrapping was set to 2000 samples, and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were incorporated to enhance the robustness and accuracy of the analysis67.

The CFA and mediation analyses utilized various fit indices for model evaluation, including the Chi-square test, comparative fit index (CFI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Adequate model fit was indicated by a nonsignificant Chi-square (p > 0.05), χ2/df < 5, CFI and GFI values exceeding 0.95, and RMSEA values below 0.0868,69. However, considering the sensitivity of the Chi-square test to sample size, the model fit estimation was primarily based on CFI, GFI, and RMSEA values70.

Ethical statement

Each participant provided written informed consent before participating in the study. Ethical approval was secured from the Institute Human Ethics Committee of the authors’ affiliated institution, adhering to the ethical standards outlined in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Participants received non-monetary rewards as compensation for their time.

Results

Exploratory factor analysis

An EFA was conducted on the pilot study data (N = 300) for all eight items of the measuring scale. The analysis yielded insufficient communality for the item “I enjoy deliberately irritating other players while playing multiplayer games in social networking sites.” Moreover, many of the participants (47.33%) reported that they were not engaged in multiplayer games. Consequently, this item was excluded from further analyses.

The remaining seven items were subjected to another iteration of EFA on the same data. Firstly, the skewness and kurtosis values remained under the prescribed thresholds of 2 and 7, respectively, suggesting a normal distribution of the data71. The analysis demonstrated robust sample adequacy, evidenced by a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test score of 0.7872. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded a prominent result (χ2 = 714.35, p < 0.001), indicating the suitability of factor analysis for the dataset72. Communalities obtained through principal axis factoring were above the 0.40 threshold, underscoring the strength and coherence of all seven items. The selection of components for extraction was guided by the Kaiser criterion, which recommends retaining factors with eigenvalues greater than one73. Following these guidelines, the EFA yielded a two-factor solution for the seven items of the GAATPB scale, satisfying the eigenvalue criterion (active trolling = 3.28, passive bystanderism = 1.17). The criteria for item retention also included factor loadings above 0.50 or parallel loadings below 0.2074. Table 1 presents the items associated with each factor and provides the rotated component matrix of all seven items. Furthermore, the GAATPB scale exhibited adequate internal consistency, as indicated by Cronbach’s α of 0.8175. The two factors within the scale, active trolling (Cronbach’s α = 0.70) and passive bystanderism (Cronbach’s α = 0.82), also demonstrated satisfactory reliability values75.

Confirmatory factor analysis

A CFA was conducted on the field study data (N = 497) to ascertain the model fit for the overall sample. The results indicated (see Fig. 1) an adequate fit of the model73, which was corroborated by various goodness-of-fit indices (CFI = 0.98; GFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.06), except for the Chi-square (χ2 = 34.34, p < 0.01, χ2/df = 2.82).

Correlation and hierarchical multiple regression analyses

Table 2 indicates the descriptive values and correlations between the trolling dimensions, agreeableness, and DT traits. The zero-order correlations showed significant associations between all the examined variables, supporting hypotheses 1a and 1b. Notably, agreeableness was negatively associated with all four DT traits, active trolling, and passive bystanderism. Further, DT traits were positively associated with both the trolling dimensions.

Subsequent to the correlation, two-step hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted separately for active trolling and passive bystanderism. Prior to the analyses, standard assumptions of the regression were verified. To begin with, outliers exceeding three standard deviations were excluded to ensure data integrity. Additionally, the outcomes indicated no collinearity between the independent variables on both the trolling dimensions (VIF < 10 and tolerance > 0.1). Further, no autocorrelation was detected in the residual terms for either active trolling (Durbin–Watson value = 2.04) or passive bystanderism (Durbin–Watson value = 1.93), satisfying the criteria for independent errors. The analyses also confirmed the normal distribution of errors, homogeneity of variance, and linearity. The details of these assumptions are illustrated with suitable graphs and tables in the supplementary data.

The hierarchical regression analyses aimed to assess whether adding different variables accounted for the change in variance of the preceding predictor on the trolling dimensions (see Table 3). In the first step, agreeableness was introduced as a predictor, accounting for 8.6% of the total variance on active trolling [R2 = 0.09, F(1, 495) = 46.75, p < 0.01] and 4.6% of the total variance on passive bystanderism [R2 = 0.05, F(1, 495) = 25.09, p < 0.01], thus serving as a unique predictor for both dimensions.

The second step involved adding DT traits, which significantly explained 27% of the total variance on active trolling [R2 = 0.28, F(5, 491) = 37.60, p < 0.01] and 23.6% of the total variance on passive bystanderism [R2 = 0.24, F(5, 491) = 31.22, p < 0.01]. The change of variance for both active trolling (ΔR2 = 0.19, F(4, 491) = 32.35, p < 0.01) and passive bystanderism [ΔR2 = 0.19, F(4, 491) = 31.22, p < 0.01] was statistically significant.

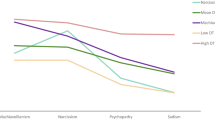

The results did not support hypotheses 2a and 2b, suggesting that both narcissism and Machiavellianism emerged as predictors of active trolling and passive bystanderism. Furthermore, the overall findings of the regression analyses indicated that psychopathy was the strongest predictor (β = 0.19, p < 0.01) of active trolling (see Table 3). On the other hand, while narcissism emerged as the strongest predictor (β = 0.20, p < 0.01) of passive bystanderism, psychopathy did not significantly predict (p = 0.09) passive bystanderism (see Table 3). Notably, with the inclusion of DT traits, agreeableness ceased to be a significant predictor of both active trolling (p = 0.14) and passive bystanderism (p = 0.99). These results supported the premise that DT traits mediate the relationship between agreeableness and trolling behaviors.

Mediation analyses

The mediating role of DT traits in the relationship between agreeableness and trolling dimensions was assessed using two separate SEMs. In the first model, active trolling was assessed as the dependent variable (SEM 1), and the second model focussed on passive bystanderism (SEM 2). Although Baron and Kenny76 recommend prefacing a full mediation model with a direct effect model, the absence of degrees of freedom precluded determining model fit for the direct effect. Furthermore, regression coefficients were previously established via hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Consequently, this study proceeded to test the hypothesized relationships directly using full mediation models in both SEM 1 and SEM 2. The mediation analyses employed a bias-corrected bootstrap estimation, with a specified bootstrap sample of 2000. Table 4 outlines the model pathways, which are considered significant if the 95% CIs do not encompass zero.

The mediating role of DT traits between agreeableness and active trolling

SEM 1 (see Fig. 2) examined the direct effect of agreeableness on active trolling and its indirect effect through DT traits. This model, reflecting the hypothesized relationships, indicated a good fit across a range of model fit indices (CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06), with the exception of the Chi-square statistic (χ2 = 25.25, p < 0.01, χ2/df = 3.15).

The standardized path coefficients revealed that the indirect effect of agreeableness on active trolling (β = − 0.31, 95% CI = − 0.40 to − 0.24) was significant (see Table 4). However, with the inclusion of DT traits, there was no significant direct effect of agreeableness on active trolling (β = 0.02, 95% CI = − 0.07 to 0.12). The results supported hypothesis 3a, suggesting that DT traits fully mediated the relationship between agreeableness and active trolling.

The mediating role of DT traits between agreeableness and passive bystanderism

Similar to SEM 1, the hypothesized relationships in SEM 2 (see Fig. 3) also displayed a strong fit across various model fit indices (CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.07), except for the Chi-square statistic (χ2 = 28.69, p < 0.01, χ2/df = 3.58).

Standardized path coefficients of the proposed SEM 2, showing the mediating effect of DT on the relationship between agreeableness and passive bystanderism. N = 497, χ2 = 28.69, p < 0.01, χ2/df = 3.58, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.06. NA narcissism, MA Machiavellianism, PS psychopathy, SA sadism.

The standardized path coefficients of SEM 2 indicated a significant indirect effect of agreeableness on passive bystanderism (β = − 0.30, 95% CI = − 0.40 to − 0.23). Yet, similar to SEM 1, including DT traits did not yield a significant direct effect of agreeableness on passive bystanderism (β = 0.08, 95% CI = − 0.10 to 0.19). Therefore, the results supported hypothesis 3b, suggesting that DT traits fully mediated the relationship between agreeableness and passive bystanderism, consistent with the results from SEM 1.

Discussion

The present study extends the conventional perception of trolling as a unidimensional interaction, typically characterized by a perpetrator directly confronting a victim on SNSs. It proposed an alternative view where trolling can manifest through bystander presence, thus expanding the concept beyond the realm of direct attacks. Firstly, this study investigated active trolling and passive bystanderism by developing the GAATPB scale. Furthermore, it also examined how variations in certain personality traits are associated with the proposed trolling dimensions.

While the association and predictive utility of traits like agreeableness and DT for active trolling are well-documented, their role in influencing passive bystanderism remains unexplored. By addressing this research gap, the present study examined the relationship and predictive utility of agreeableness and DT traits on both trolling dimensions. It also investigated whether the lack of specific characteristics, such as agreeableness (lower agreeableness), might predispose individuals to exhibit DT traits, which could lead to subsequent trolling behaviors. Considering the overarching theme of reduced empathy across both trolling dimensions and the examined personality traits, the study hypothesized that no significant differences exist between active trolling and passive bystanderism in their relationships with personality traits (hypothesis 1), the predictive utility of these traits (hypothesis 2), and the assumed mediation of DT traits in the relationship between lower agreeableness and trolling dimensions (hypothesis 3). Building on these primary hypotheses, the study further investigated the role of DT traits and lower agreeableness separately on active trolling and passive bystanderism.

The results supported hypotheses 1a and 1b, demonstrating a significant relationship between the examined personality traits and trolling dimensions. This finding is in agreement with the previous studies9,39,55, where trolling was positively associated with all DT traits and negatively with agreeableness. The study highlights that the association of these personality traits with both forms of trolling is similar. Following the correlation, hierarchical multiple regression analyses were undertaken. Initially, the results showed that lower agreeableness predicted active trolling and passive bystanderism in the first step of the analyses. Yet, with the inclusion of DT traits in the second step, it ceased to be the predictor of both trolling dimensions, contradicting the previous research1,34,39. These findings indicate that lower agreeableness would no longer influence trolling behaviors when accounted for the shared variance with DT traits, suggesting a potential mediating role of DT traits in the dynamic between agreeableness and trolling behaviors.

Contrary to hypotheses 2a and 2b, narcissism and Machiavellianism emerged as significant predictors for active trolling and passive bystanderism, challenging the assertions from previous studies9,34,39. The current findings support the theory of threatened egotism77, which posits that cyber-aggressive behaviors, such as trolling, serve as a defense mechanism for narcissists to protect their favorable self-view against perceived threats. In SNSs, these aggressive behaviors often target individuals who oppose the narcissistic views or persona of the trolls78,79. Such aggression manifests as either active trolling, characterized by derogatory comments, or passive bystanderism, involving indirect reinforcement through actions like sharing content or following troll pages.

Mirroring the concept of threatened egotism, the role of narcissism in promoting trolling behaviors is further elucidated by the phenomenon of schadenfreude. This German term describes the experience of deriving pleasure from others’ misfortune and harboring desires for their adverse outcomes80. Schadenfreude is closely associated with increased levels of narcissism and the act of downward social comparison81, often driven by a need for self-enhancement. Consequently, individuals with lower self-esteem and negative self-perceptions are more prone to schadenfreude upon witnessing others’ failures through the act of trolling82,83. Narcissistic tendencies, such as schadenfreude, are primarily witnessed in the passive observation of others’ suffering, providing a subtler form of gratification that is considered illegitimate, given its lack of acquisition through direct competition84. Such a tendency is also reflected in the current findings, as narcissism emerged as the most robust predictor of passive bystanderism, which was devoid of prediction from a more callous psychopathic trait.

Similarly, individuals with pronounced Machiavellian tendencies often employ manipulation tactics, such as inducing feelings of shame or guilt, in their online social interactions85. Rauthmann86 describes this as protective self-monitoring, where Machiavellian individuals continually adjust their behavior for social advantage and control. In the context of internet trolling, these tendencies can lead to subtle forms of manipulation, such as gaslighting or disseminating misinformation. The immediacy and anonymity of SNSs can amplify active trolling and passive bystanderism, providing a platform for individuals with high levels of narcissism and Machiavellianism to assert dominance or manipulate others without apparent consequences.

Interestingly, although the study did not formulate specific hypotheses, the results revealed a differential impact of psychopathy across trolling dimensions. While psychopathy emerged as the strongest predictor of active trolling, it did not predict passive bystanderism. This finding aligns with the notion that individuals with high psychopathic tendencies are attracted to the excitement of causing online disruptions, consistent with their thrill-seeking tendencies14. Additionally, the deceptive nature of active trolling harmonizes with the callous and unemotional traits typically seen in psychopathy, along with their manipulative interpersonal style87. The bullying behavior, regardless of whether it transpires offline or online, will keep psychopaths motivated and committed to their impulsive ideas as it makes them feel good to instigate distress in others.

However, the findings reflect that being a passive bystander to the troll and not participating in it does not support callous and unemotional impulsivity; hence, it is uncertain that such an individual possesses psychopathic tendencies. Although closely related to psychopathy, trait sadism was found to be a predictor of both active trolling and passive bystanderism, corroborating previous studies1,9. Individuals who engage in active trolling on SNSs often taunt and humiliate others, actively seeking such opportunities63. Moreover, those with pronounced sadistic traits are characterized not only by their direct involvement in online aggression but also by deriving pleasure from observing and endorsing such behaviors. The study suggests that while passive bystander trolls may not exhibit overt psychopathic traits, the presence of sadistic tendencies could contribute to their engagement in and reinforcement of trolling behaviors.

The results from the mediation analyses revealed that DT traits fully mediated the relationship between lower agreeableness and both active trolling, as well as passive bystanderism, thereby affirming hypotheses 3a and 3b, respectively. Individuals characterized by lower agreeableness tend to prioritize their own needs, engage in manipulative behaviors, and exhibit aggressive tendencies88,89. Crucially, they show a significant lack of empathy towards others90. Studies on empathy45,59,91 indicate that while the DT exhibits some correlation with empathic concern, it does not significantly predict a lack of empathy beyond the influence of lower agreeableness. These findings imply that a certain degree of cognitive apathy, fueled by lower agreeableness, might be necessary for engaging in harmful behaviors like trolling. This inherent lack of empathy and increased likelihood of adversarial behavior might also predispose those with lower agreeableness to adopt passive bystander roles. Rather than intervening or offering support to victims, their reduced empathetic engagement and propensity for contentiousness might lead them to either ignore the distress of others or derive satisfaction from observing conflict without direct participation. Such passive bystander behavior can thus be seen as an extension of their broader interpersonal conduct, where a deficiency in positive social engagement and a predisposition towards antagonism influence their actions (or inactions) within both direct and vicarious social interactions. Therefore, it is logical to assert low agreeableness as a common denominator underlying dark personality traits and both active trolling and passive bystanderism. Consequently, the study emphasizes that trolling behavior stems not merely from lower agreeableness but also from a lack of consensus, triggered by the activation of inherent dark traits.

The issue of lower agreeableness and manifestations of dark personalities hold significant implications for online mental health, impacting not only the individuals exhibiting these traits but also their victims and society at large. Considering this, lower agreeableness and dark personalities warrant increased research attention. This is particularly crucial in understanding their correlation and influence on internet trolling, a growing concern in the digital age. There remains much to explore about the underlying processes and factors associated with these personality traits and their role in fostering a range of online deviant behaviors, which can further exacerbate the negative impacts on individual and societal mental health.

While this study contributes to the understanding of bystander behavior in trolling literature, it is not without limitations. One primary limitation is the scope of the GAATPB scale developed for this study. The scale did not encompass the multidimensionality of bystander trolling, suggesting that future research should broaden this scope to include positive bystander interventions. Additionally, the survey research method provided valuable insights but did not deeply explore the phenomenological aspects of trolling, such as subjective experiences, motivations, and emotions. Future studies should incorporate methodologies that probe these subjective dimensions. Another limitation is the cumulative assessment of dark personality traits. A more nuanced exploration of these traits in a continuum (such as primary and secondary psychopathy) could yield deeper insights into the underlying mechanisms of trolling behavior55. The study also suggests a more granular approach to examining trolling within specific domains of SNSs, acknowledging that trolling behaviors may vary substantially across different online platforms, such as Facebook or dating apps. Lastly, the study recognizes the potential impact of target attributes on trolling behaviors35. Future research incorporating these elements could offer a more holistic view of both trolls and their targets, enhancing the understanding of trolling dynamics.

Conclusion

This study investigated active trolling and passive bystanderism and their relationship with personality traits by developing the GAATPB scale. The investigators examined how DT traits and agreeableness correlate with and predict these trolling behaviors. The findings showed a significant relationship between DT traits and agreeableness with active trolling and passive bystanderism, highlighting a shared psychological basis for these behaviors. Notably, while psychopathy emerged as the strongest predictor for active trolling, it did not predict passive bystanderism. In contrast, trait sadism was a consistent predictor for both, emphasizing its role in online misconduct. This study also challenged previous notions by demonstrating that narcissism and Machiavellianism significantly predicted trolling behaviors. Furthermore, the findings indicate that trolling behavior, while stemming from lower agreeableness, is effectively mediated by the DT traits.

Data availability

The associated data can be requested by contacting the corresponding author.

Change history

15 May 2024

The original online version of this Article was revised: In the original version of this Article, the ORCiD IDs for the authors were omitted, which have been added.

References

Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D. & Paulhus, D. L. Trolls just want to have fun. Pers. Individ. Differ. 67, 97–102 (2014).

Navarro-Carrillo, G., Torres-Marín, J. & Carretero-Dios, H. Do trolls just want to have fun? Assessing the role of humor-related traits in online trolling behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 114, 106551 (2021).

Coles, B. A. & West, M. Trolling the trolls: Online forum users constructions of the nature and properties of trolling. Comput. Hum. Behav. 60, 233–244 (2016).

Lee, S. Y., Yao, M. Z. & Su, L.Y.-F. Expressing unpopular opinion or trolling: Can dark personalities differentiate them?. Telematics Inform. 63, 101645 (2021).

Hardaker, C. Trolling in asynchronous computer-mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions (2010).

Caplan, S. E. The Changing Face of Problematic Internet Use: An Interpersonal Approach (Peter Lang International Academic Publishers, 2018).

Nicol, S. Cyber-bullying and trolling. Youth Stud. Aust. 31, 3–4 (2012).

Binns, A. DON’T FEED THE TROLLS! Managing troublemakers in magazines’ online communities. J. Pract. 6, 547–562 (2012).

Craker, N. & March, E. The dark side of Facebook®: The Dark Tetrad, negative social potency, and trolling behaviours. Pers. Individ. Differ. 102, 79–84 (2016).

Klempka, A. & Stimson, A. Anonymous communication on the internet and trolling. Concordia J. Commun. Res. 1, 2 (2014).

Dynel, M. “Trolling is not stupid”: Internet trolling as the art of deception serving entertainment. Intercult. Pragmat. 13, 353–381 (2016).

Sanfilippo, M. R., Fichman, P. & Yang, S. Multidimensionality of online trolling behaviors. Inf. Soc. 34, 27–39 (2018).

Bishop, J. The effect of de-individuation of the Internet troller on criminal procedure implementation: An interview with a hater. Int. J. Cyber Criminol. 7, 28–48 (2013).

Sest, N. & March, E. Constructing the cyber-troll: Psychopathy, sadism, and empathy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 119, 69–72 (2017).

Hamarta, E., Muhammed, A. & Deniz, M. Development of online trolling scale: Validity and reliability study. Turk. Psychol. Couns. Guid. J. 11, 457–470 (2021).

Machackova, H., Dedkova, L. & Mezulanikova, K. Brief report: The bystander effect in cyberbullying incidents. J. Adolesc. 43, 96–99 (2015).

Bastiaensens, S. et al. ‘Can I afford to help?’ How affordances of communication modalities guide bystanders’ helping intentions towards harassment on social network sites. Behav. Inf. Technol. 34, 425–435 (2015).

Anderson, J., Bresnahan, M. & Musatics, C. Combating weight-based cyberbullying on Facebook with the dissenter effect. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 17, 281–286 (2014).

Allison, K. R. & Bussey, K. Cyber-bystanding in context: A review of the literature on witnesses’ responses to cyberbullying. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 65, 183–194 (2016).

Ferreira, P. C., Simão, A. V., Ferreira, A., Souza, S. & Francisco, S. Student bystander behavior and cultural issues in cyberbullying: When actions speak louder than words. Comput. Hum. Behav. 60, 301–311 (2016).

Brody, N. & Vangelisti, A. L. Bystander intervention in cyberbullying. Commun. Monogr. 83, 94–119 (2016).

Salmivalli, C. Bullying and the peer group: A review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 15, 112–120 (2010).

Obermaier, M., Fawzi, N. & Koch, T. Bystanding or standing by? How the number of bystanders affects the intention to intervene in cyberbullying. New Media Soc. 18, 1491–1507 (2016).

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C. & Lampe, C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J. Comput. Mediat. Commun. 12, 1143–1168 (2007).

Rudnicki, K., Vandebosch, H., Voué, P. & Poels, K. Systematic review of determinants and consequences of bystander interventions in online hate and cyberbullying among adults. Behav. Inf. Technol. 42, 527–544 (2023).

Paulhus, D. L. & Williams, K. M. The dark triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. J. Res. Pers. 36, 556–563 (2002).

Paulhus, D. L. Toward a taxonomy of dark personalities. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 23, 421–426 (2014).

Brown, K. W. & Kasser, T. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Soc. Indic. Res. 74, 349–368 (2005).

Buffardi, L. E. & Campbell, W. K. Narcissism and social networking web sites. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 34, 1303–1314 (2008).

Jakobwitz, S. & Egan, V. The dark triad and normal personality traits. Pers. Individ. Differ. 40, 331–339 (2006).

Hare, R. D. Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths among Us (Guilford Press, 1999).

Paulhus, D. L. & Dutton, D. G. Everyday sadism (American Psychological Association, 2016).

Kircaburun, K. & Griffiths, M. D. The dark side of internet: Preliminary evidence for the associations of dark personality traits with specific online activities and problematic internet use. J. Behav. Addctn. 7, 993–1003 (2018).

Gylfason, H. F., Sveinsdottir, A. H., Vésteinsdóttir, V. & Sigurvinsdottir, R. Haters gonna hate, trolls gonna troll: The personality profile of a Facebook troll. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 5722 (2021).

Lopes, B. & Yu, H. Who do you troll and why: An investigation into the relationship between the Dark Triad Personalities and online trolling behaviours towards popular and less popular Facebook profiles. Comput. Hum. Behav. 77, 69–76 (2017).

Cohen, A. Are they among us? A conceptual framework of the relationship between the dark triad personality and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 26, 69–85 (2016).

Buckels, E. E., Jones, D. N. & Paulhus, D. L. Behavioral confirmation of everyday sadism. Psychol. Sci. 24, 2201–2209 (2013).

Zezulka, L. A. & Seigfried-Spellar, K. Differentiating cyberbullies and internet trolls by personality characteristics and self-esteem (2016).

March, E., McDonald, L. & Forsyth, L. Personality and internet trolling: A validation study of a Representative Sample. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 1–4 (2023).

Kokkinos, C. M., Baltzidis, E. & Xynogala, D. Prevalence and personality correlates of Facebook bullying among university undergraduates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 55, 840–850 (2016).

Karl, K., Peluchette, J. & Schlaegel, C. Who’s posting Facebook faux pas? A cross-cultural examination of personality differences. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 18, 174–186 (2010).

Baldasare, A., Bauman, S., Goldman, L. & Robie, A. Chapter 8 cyberbullying? Voices of college students. In Misbehavior Online in Higher Education 127–155 (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 2012).

McCullough, M. E., Bellah, C. G., Kilpatrick, S. D. & Johnson, J. L. Vengefulness: Relationships with forgiveness, rumination, well-being, and the Big Five. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 27, 601–610 (2001).

Zhou, Y., Zheng, W. & Gao, X. The relationship between the big five and cyberbullying among college students: The mediating effect of moral disengagement. Curr. Psychol. 38, 1162–1173 (2019).

Moshagen, M., Zettler, I., Horsten, L. K. & Hilbig, B. E. Agreeableness and the common core of dark traits are functionally different constructs. J. Res. Pers. 87, 103986 (2020).

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H. & Meijer, E. The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the dark triad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 12, 183–204 (2017).

Vize, C. E., Miller, J. D. & Lynam, D. R. Antagonism in the dark triad. In The Handbook of Antagonism 253–267 (Academic Press, 2019).

Book, A. et al. Unpacking more “evil”: What is at the core of the dark tetrad?. Pers. Individ. Differ. 90, 269–272 (2016).

Andershed, H. A., Kerr, M., Stattin, H. & Levander, S. Psychopathic traits in non-referred youths: A new assessment tool (2002).

Sherman, W. R. & Craig, A. B. Understanding Virtual Reality: Interface, Application, and Design (Morgan Kaufmann, 2018).

Vize, C. E., Collison, K. L., Miller, J. D. & Lynam, D. R. Examining the effects of controlling for shared variance among the dark triad using meta-analytic structural equation modelling. Eur. J. Pers. 32, 46–61 (2018).

Samuel, D. B. & Widiger, T. A. A meta-analytic review of the relationships between the five-factor model and DSM-IV-TR personality disorders: A facet level analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 28, 1326–1342 (2008).

Saucier, G. Orthogonal markers for orthogonal factors: The case of the Big Five. J. Res. Pers. 36, 1–31 (2002).

Lynam, D. R. & Miller, J. D. The basic trait of antagonism: An unfortunately underappreciated construct. J. Res. Pers. 81, 118–126 (2019).

March, E. Psychopathy, sadism, empathy, and the motivation to cause harm: New evidence confirms malevolent nature of the Internet Troll. Pers. Individ. Differ. 141, 133–137 (2019).

Barlińska, J., Szuster, A. & Winiewski, M. Cyberbullying among adolescent bystanders: Role of affective versus cognitive empathy in increasing prosocial cyberbystander behavior. Front. Psychol. 9, 799 (2018).

Taylor, S. H., DiFranzo, D., Choi, Y. H., Sannon, S. & Bazarova, N. N. Accountability and empathy by design: Encouraging bystander intervention to cyberbullying on social media. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 3, 1–26 (2019).

Zhao, Y., Chu, X. & Rong, K. Cyberbullying experience and bystander behavior in cyberbullying incidents: The serial mediating roles of perceived incident severity and empathy. Comput. Hum. Behav. 138, 107484 (2023).

Pajevic, M., Vukosavljevic-Gvozden, T., Stevanovic, N. & Neumann, C. S. The relationship between the Dark Tetrad and a two-dimensional view of empathy. Pers. Individ. Differ. 123, 125–130 (2018).

Heym, N., Firth, J., Kibowski, F. & Sumich, A. Empathy at the heart of darkness: Empathy deficits that bind the dark triad and those that mediate indirect relational aggression. Front. Psychiatry 10, 437855 (2019).

Graziano, W. G., Habashi, M. M., Sheese, B. E. & Tobin, R. M. Agreeableness, empathy, and helping: A person × situation perspective. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 93, 583 (2007).

Jonason, P. K. & Webster, G. D. The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychol. Assess. 22, 420 (2010).

O’Meara, A., Davies, J. & Hammond, S. The psychometric properties and utility of the Short Sadistic Impulse Scale (SSIS). Psychol. Assess. 23, 523 (2011).

John, O. P. & Srivastava, S. The Big-Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Theoretical Perspectives (University of California, 1999).

Haynes, S. N., Richard, D. & Kubany, E. S. Content validity in psychological assessment: A functional approach to concepts and methods. Psychol. Assess. 7, 238 (1995).

van Geel, M., Goemans, A., Toprak, F. & Vedder, P. Which personality traits are related to traditional bullying and cyberbullying? A study with the Big Five, Dark Triad and sadism. Pers. Individ. Differ. 106, 231–235 (2017).

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M. & Williams, J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 39, 99–128 (2004).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 6, 1–55 (1999).

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A. & King, J. Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. J. Educ. Res. 99, 323–338 (2006).

Bentler, P. M. Fit indexes, Lagrange multipliers, constraint changes and incomplete data in structural models. Multivar. Behav. Res. 25, 163–172 (1990).

Kim, H.-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor. Dent. Endod. 38, 52 (2013).

Williams, B., Onsman, A. & Brown, T. Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices. Australas. J. Paramed. 8, 1–13 (2010).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E. & Tatham, R. L. Multivariate Data Analysis 5th edn, 207–219 (Prentice Hall, 1998).

Comrey, A. L. & Lee, H. B. A First Course in Factor Analysis (Psychology Press, 2013).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18, 39–50 (1981).

Baron, R. M. & Kenny, D. A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 51, 1173 (1986).

Baumeister, R. F., Bushman, B. J. & Campbell, W. K. Self-esteem, narcissism, and aggression: Does violence result from low self-esteem or from threatened egotism?. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 9, 26–29 (2000).

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Eisenberg, N. & Maffei, C. Relations of proactive and reactive dimensions of aggression to overt and covert narcissism in nonclinical adolescents. Aggress. Behav. 36, 21–27 (2010).

Lobbestael, J., Baumeister, R. F., Fiebig, T. & Eckel, L. A. The role of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in self-reported and laboratory aggression and testosterone reactivity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 69, 22–27 (2014).

Dalakas, V., Phillips Melancon, J. & Sreboth, T. A qualitative inquiry on schadenfreude by sport fans. J. Sport Behav. 38, 161–179 (2015).

Ouwerkerk, J. W. & Johnson, B. K. Motives for online friending and following: The dark side of social network site connections. Soc. Media Soc. 2, 2056305116664219 (2016).

Van Dijk, W. W., van Koningsbruggen, G. M., Ouwerkerk, J. W. & Wesseling, Y. M. Self-esteem, self-affirmation, and schadenfreude. Emotion 11, 1445 (2011).

Brubaker, P. J., Montez, D. & Church, S. H. The power of schadenfreude: Predicting behaviors and perceptions of trolling among Reddit users. Soc. Media Soc. 7, 20563051211021382 (2021).

Leach, C. W., Spears, R., Branscombe, N. R. & Doosje, B. Malicious pleasure: Schadenfreude at the suffering of another group. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84, 932 (2003).

Austin, E. J., Farrelly, D., Black, C. & Moore, H. Emotional intelligence, Machiavellianism and emotional manipulation: Does EI have a dark side?. Pers. Individ. Differ. 43, 179–189 (2007).

Rauthmann, J. F. Acquisitive or protective self-presentation of dark personalities? Associations among the Dark Triad and self-monitoring. Pers. Individ. Differ. 51, 502–508 (2011).

March, E. & Steele, G. High esteem and hurting others online: Trait sadism moderates the relationship between self-esteem and internet trolling. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 23, 441–446 (2020).

Dåderman, A. M. & Ragnestål-Impola, C. Workplace bullies, not their victims, score high on the Dark Triad and Extraversion, and low on Agreeableness and Honesty-Humility. Heliyon 5, e02609 (2019).

Miller, J. D., Gaughan, E. T., Maples, J. & Price, J. A comparison of agreeableness scores from the Big Five Inventory and the NEO PI-R: Consequences for the study of narcissism and psychopathy. Assessment 18, 335–339 (2011).

Butrus, N. & Witenberg, R. T. Some personality predictors of tolerance to human diversity: The roles of openness, agreeableness, and empathy. Aust. Psychol. 48, 290–298 (2013).

Kajonius, P. J. & Björkman, T. Individuals with dark traits have the ability but not the disposition to empathize. Pers. Individ. Differ. 155, 109716 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Prof. Erin Buckels and Prof. Evita March for their pioneering work in the field of trolling, which inspired this research. Additionally, the authors thank all the participants who generously dedicated their time to the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.U. Methodology: A.U. Investigation: A.U. Visualization: A.U., S.P.K. Supervision: S.P.K. Writing—original draft: A.U., S.P.K. Writing—review and editing: S.P.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ubaradka, A., Khanganba, S. The differential effect of psychopathy on active and bystander trolling behaviors: the role of dark tetrad traits and lower agreeableness. Sci Rep 14, 9905 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60203-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60203-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.