Abstract

The Strecker Synthesis of (a)chiral α-amino acids from simple organic compounds, such as ammonia (NH3), aldehydes (RCHO), and hydrogen cyanide (HCN) has been recognized as a viable route to amino acids on primordial earth. However, preparation and isolation of the simplest hemiaminal intermediate – the aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH)– formed in the Strecker Synthesis to even the simplest amino acid glycine (H2NCH2COOH) has been elusive. Here, we report the identification of aminomethanol prepared in low-temperature methylamine (CH3NH2) – oxygen (O2) ices upon exposure to energetic electrons. Isomer-selective photoionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PI-ReTOF-MS) facilitated the gas phase detection of aminomethanol during the temperature program desorption (TPD) phase of the reaction products. The preparation and observation of the key transient aminomethanol changes our perception of the synthetic pathways to amino acids and the unexpected kinetic stability in extreme environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

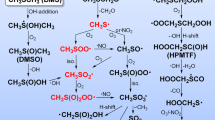

Since 1850, the Strecker Synthesis—a series of chemical reactions synthesizing (a)chiral α-amino acids from ammonia (NH3), aldehydes (RCHO), and hydrogen cyanide (HCN) (Fig. 1)1,2,3,4,5 has received extensive recognition as a conceivable route to amino acids such as glycine on primordial Earth6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. Even so, the preparation and identification of one of the key intermediate of the Strecker Synthesis to the simplest amino acid glycine (H2NCH2COOH)—the aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH) hemiaminal—has been elusive15,16,17. Earlier attempts to synthesize aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH; 1; Fig. 2) in laboratories were unsuccessful due to the facile decomposition to water (H2O) and methanimine (CH2NH), which eventually converts to hexamethylenetetramine (C6H12N4), in aqueous media15. However, computational investigations revealed that 1 is kinetically stable toward dehydration to methanimine in the gas phase with a substantial barrier between 230 and 234 kJ mol−1 separating aminomethanol from the unimolecular decomposition products17,18. The gas phase reactions of water (H2O) with methanimine (CH2NH) and ammonia (NH3) with formaldehyde (H2CO) to yield 1 involve high energy barriers of 194–252 kJ mol−1 and 130–171 kJ mol−1, respectively (reactions (5) and (1); Fig. 1)17,18. The sublimation of reaction products formed through a thermal chemistry of ammonia (NH3) and formaldehyde (H2CO) in water (H2O) rich ices resulted in ion counts at mass-to-charge (m/z) of 47, but the ionization of the neutrals by electron impact could not assign the nature of the structural isomer(s)19. An alternative pathway to 1 could comprise the barrierless insertion of an electronically excited oxygen atom (O(1D)) into a carbon-hydrogen bond of the methyl group of methylamine (reaction (6); Fig. 1)20,21,22 followed by stabilization of the aminomethanol insertion product either by a third body collision in the gas phase or through energy transfer processes to the surrounding molecules within an icy matrix. Furthermore, the rate of unimolecular decomposition of aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH) to methanimine (CH2NH) will significantly reduce in a non-aqueous medium containing reactants methylamine and oxygen. In a water-rich environment, the surrounding water molecules could act as a catalyst in the dehydration process of aminomethanol23 and therefore could obscure its detection.

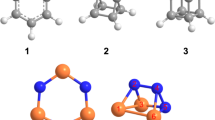

Ranges of calculated adiabatic ionization energies (IEs) accounting for the error limits and relative energies (∆E) calculated at the CCSD(T)/CBS//CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ level of theory in eV and kJ mol−1, respectively. Geometrical parameters, bond length, and angles are provided in picometer and degrees, respectively. Cartesian coordinates of the structures and their calculated vibrational frequencies are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and 2, respectively.

In this work, we report the preparation of the previously elusive transient aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH; 1) in low-temperature binary ices of methylamine (CH3NH2) and oxygen (O2) along with its gas phase detection. Isomer-selective photoionization reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometry and isotopic substitution experiments confirmed the synthesis of 1 in our molecular system. Barrierless insertion of O(1D) into a carbon-hydrogen bond of the methyl group of the methylamine molecule leads to the formation of 1 followed by stabilization in the ice matrix. The methodology presented here could also be useful to prepare higher order hemiaminals (RCH(OH)NH2) from corresponding primary or secondary amines.

Results

Experimental scheme

The experiments were performed in an ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) surface science machine at a base pressure of 9 ± 1 × 10−11 Torr (Supplementary Fig. 1)24,25. Binary ices of methylamine (CH3NH2)–oxygen (O2), d5-methylamine (CD3ND2)–oxygen (O2), and methylamine (CH3NH2)– O18-oxygen (18O2) were prepared in separate experiments at thicknesses of 239 ± 24 nm at 5.0 ± 0.2 K and oxygen to methylamine ratios of 9 ± 1: 1 (Supplementary Methods). Bond-cleavage processes in the ice mixtures were triggered by exposing the oxygen-rich ices to energetic electrons at average doses of typically 18 ± 2 eV molecule−1 (Supplementary Table 1). Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of the ices were collected online and in situ during the radiation exposure to monitor chemical changes in the systems (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2). The stretching frequencies of hydroxy (−OH) and amino (−NH2) functional groups of aminomethanol are expected to appear at 3659 and 3146 cm−1 (scaled), respectively, (Supplementary Fig. 2). However, broad absorption in the region 3680–3000 cm−1 due to overlapping infrared absorptions of products carrying amino (–NH2) and hydroxy functional groups (–OH) obscure the explicit identification of aminomethanol via FTIR spectroscopy (Supplementary Table 2) in these multi-component ice mixtures. Therefore, a novel methodology is required to identify isomers of unstable molecules in complex molecular mixtures selectively. Here, the products formed in the irradiated ices along with the reactants were sublimed by increasing the temperature of the sample to 320 K at a rate of 1 K min−1 (temperature program desorption; TPD). The subliming neutral molecules were ionized exploiting isomer-selective vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) photoionization (PI) (Supplementary Table 3)26,27,28,29,30. The ions formed were then mass resolved in a reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometer (PI-ReTOF-MS). By systematically tuning the photon energies below and above the ionization energy (IE) of the isomer of interest, isomers (1–5) of aminomethanol can be selectively ionized based on their adiabatic ionization energies to ultimately elucidate which isomer(s) is (are) formed. The computed molecular structures of distinct CH5NO isomers 1–5 are depicted in Fig. 2 along with their adiabatic ionization energies (IEs), relative energies, and geometrical parameters. The IEs and relative energies of the isomers calculated at the CCSD(T)/CBS level of theory with CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ zero-point vibrational energy corrections are provided in Supplementary Table 4. Optimized geometrical coordinates and calculated frequencies of the isomers are provided in Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Data 2, respectively. It is important to stress here that the calculated IEs of the isomers can be lower by 0.05 eV or higher by 0.02 eV based on a comparison of experimental and calculated IEs of molecular benchmark systems31. Further, ReTOF-MS calibration experiments revealed that the electric field of the ion optics lowers the IE by 0.03 eV32.

Mass spectrometry

The mass spectra of the species subliming from the irradiated ice mixtures are collected as a function of temperature at photon energies of 9.50 and 9.10 eV (Fig. 3). At 9.50 eV, all isomers (1)–(5)—if formed—can be ionized; at 9.10 eV, all isomers except (1) can be ionized. Data recorded at 9.50 eV reveal prominent product signal at mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) of 42 (CH2N2), 43 (C2NH5+), 45 (CH3NO/C2H7N), 47 (CH5NO), 58 (C2H6N2), 59 (C3H9N), 60 (C2H8N2), 61 (CH3NO2), 74 (C2H6N2O), and 90 (C2H6N2O2/C3N3H12) along with the reactant signal at m/z = 31 (CH3NH2). Signals at m/z = 60 (C2H8N2), 59 (C3H9N), and 58 (C2H6N2) were previously observed in processed pure methylamine ice and can be tentatively assigned to isomers of ethylene diamine, N-methyl-ethanamine and N-methylformimidamide33. A possible formation pathway of ethylene diamine (C2H8N2) could follow a radical–radical recombination of two •CH2NH2 radicals33. N-methyl-ethanamine (C3H9N) could generate via recombination of •CH3 and •CH2NHCH3 radicals, while N-methylformimidamide (C2H6N2) could generate via dehydrogentation of ethylene diamine (C2H8N2). Oxygen could insert at the C–H and/or N–H bonds of N-methylformimidamide to generate products observed at m/z = 74 (C2H6N2O) and 90 (C2H6N2O2). It is important to note here that mass signals 47, 61, 74, and 90 were not observed in pure methylamine ices33.

In a control experiment, in which PI-ReTOF-MS data were collected under the same experimental conditions, but without exposing the ices to energetic electrons, no product signal was observed (Supplementary Fig. 3). Therefore, in the aforementioned experiments, signal detected at m/z = 45, 47, 58, and 60 can be only linked to the processing of the ices by energetic electrons, but not to ion-molecule reactions in the gas phase of the reactant molecules. The TPD profile at m/z = 47 recorded at a photon energy of 9.50 eV reveals a single sublimation event peaking at 210 K (Fig. 4a). This signal can be associated with a product of a molecular formula CH5NO. Recall that at 9.50 eV, all the isomers 1–5 can be photoionized. Upon lowering the photon energy to 9.10 eV—a photon energy where only isomers 2–5 can be ionized—no ion counts could be observed (Fig. 4b). These data document that the ion signal observed at m/z = 47 is connected to the previously elusive aminomethanol conformers 1a-b; the latter could not be discriminated since their ionization energies overlap within the error limits. To confirm the molecular formula of the product, isotopic substitution experiments were conducted with CH3NH2–18O2 and CD3ND2–O2 ice mixtures. The peak sublimation temperature of the TPD profiles collected at m/z = 49 and 52 in the CH3NH2–18O2 and CD3ND2–O2 systems, respectively, are in excellent agreement with the peak sublimation temperature of 210 K recorded for m/z = 47 in the CH3NH2–O2 system (Fig. 5); this also confirms a shift of the ion signal (m/z = 47) by 2 amu and 5 amu revealing the presence of a single oxygen atom and five hydrogen atoms. The broadening of the TPD profile at m/z = 49 in the CH3NH2–18O2 ice close to 200 and 230 K could be due to the fragmentation of higher masses observed at m/z = 91 (C2H3N218O2) and 80 (CH4N218O2) (Supplementary Fig. 4). Product observed at mass 91 could fragment to CH2N2+ (m/z = 42) and HCO2+ (m/z = 49) ions, the later fragment could add to the ion counts at m/z = 49 around 200 K. Similarly, product observed at m/z = 80 could fragment to generate N2H3+ (m/z = 31) and HCO2+ (m/z = 49) ions; the later fragment will increase the ion counts at m/z = 49 near 230 K causing broadening of the TPD profile of our target molecule. In CH3NH2–O2 and CD3ND2–O2 ice systems, the ion fragment HCO2+ will appear at m/z ratio of 45 and 46, respectively, and therefore cannot appear in the mass channel of our target molecule.

(a), (b), and (c) are temperature program desorption (TPD) profiles obtained at m/z = 47, 52, and 49 during the sublimation phase of irradiated CH3NH2–O2, CD3ND2–O2, and CH3NH2–18O2 ice mixtures, respectively. The shaded region indicates the peak corresponding to the target molecule, aminomethanol. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Having provided compelling evidence on the synthesis and detection of aminomethanol in the gas phase, we shift our attention now to the identification of potential reaction mechanism(s) involved in its formation. Previous investigations of neat oxygen (O2) ices exposed to energetic electrons revealed two decomposition pathways leading to two ground-state atomic oxygens [O (3P)] and one ground state O (3P) plus an electronically excited O(1D) atom (reactions (7) and (8))34. O(1D) can insert barrierlessly into a carbon-hydrogen bond of the methyl group of the methylamine molecule forming aminomethanol followed by stabilization in the icy matrix (reaction (9))20,21. Alternatively, methylamine (CH3NH2) can undergo unimolecular dissociation to form the aminomethyl radical (•CH2NH2) radical and atomic hydrogen upon exposure to ionizing radiation (reaction (10))33,35, which may recombine with atomic oxygen to the hydroxyl radical (OH) (reaction (11)). The latter could undergo radical–radical recombination with •CH2NH2 radical if they hold a favorable recombination geometry to form aminomethanol (reaction (12)). The present experiments cannot discriminate between the insertion versus radical–radical recombination pathway.

In conclusion, we prepared aminomethanol 1 in methylamine-oxygen ices upon exposure to ionizing radiation and detected this novel molecule during the sublimation phase utilizing isomer-selective photoionization reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PI-ReTOF-MS) along with isotopic substitution experiments. Considering the distance between the ice surface and the photoionization laser of 2.0 ± 0.5 mm along with the average velocity of 307 m s−1 at 210 K, the lifetime of 1 in the gas phase has to exceed 6.5 ± 1.5 µs to survive the flight time between the ice surface and photo ionizing region. The kinetic stability of 1 is further reflected by the high decomposition energy barriers of 169 and 235 kJ mol−1 to formaldehyde (H2CO) and ammonia (NH3) and methanimine (CH2NH) and water (H2O), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5, Supplementary Table 5). The approach presented here could be helpful to prepare higher order transient hemiaminals like RCH(OH)NH2 with ‘R’ being an organic group via O(1D) insertion into the carbon-hydrogen bond of the CH2 moiety of the corresponding amines (RCH2NH2).

The present study also shows evidence of the formation of aminomethanol in astrophysical-like conditions. The methylamine (CH3NH2)-oxygen (O2) ice mixture can be appraised as a model astrophysical ice-analog. Primary amines such as methylamine (CH3NH2) and ethylamine (C2H5NH2) were observed in interstellar medium (ISM) towards SgrB2 as well as on comet 67 p/Churyumov-Gerasimenko36,37,38. Amines are also contemplated to play a critical role in the prebiotic chemistry of early Earth39,40. Analysis of the samples returned from the stardust mission revealed the presence of methylamine, ethylamine, along with glycine41. Although methylamine (CH3NH2) has only been detected in the gas phase of the interstellar medium, laboratory experiments revealed that CH3NH2 could be formed via recombination of methyl (•CH3) and amino (•NH2) radicals in a matrix cage42. Methane (CH4) and ammonia (NH3), which are precursors of •CH3 and •NH2 radicals, have been detected on icy grains;43 hence methylamine (CH3NH2) is expected to exist on interstellar grains, albeit at a lower concentration44. Oxygen (O2) was detected in the ISM much later due to observational difficulties and probably low abundance in the gas phase of ISM45. It has been suggested that the poor abundance of oxygen in the gas phase could be due to the condensation of molecular oxygen (O2) onto the interstellar grains46. Although the exact composition of molecular oxygen in the ice grains has not yet been determined, the possibility of O2 being an active reactant in the ISM cannot be neglected. Very recently, Bergner et al. investigated the formation of methanol in methane (CH4) and oxygen (O2) ice mixture and reported that oxygen insertion chemistry should be efficient on grain surfaces in cold interstellar regions such as proto-stellar cores and protoplanetary disk midplanes47.

Our laboratory experiments in astrophysical-like conditions revealed that aminomethanol could generate from amines on ice grains in proto-stellar cores or protoplanetary disks and subsequently incorporated inside comets or (and) meteorites48, which is (are) source(s) of extraterrestrial amino acids on early Earth. Aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH) could produce amino acid precursor—aminoacetonitrile (NH2CH2CN) in the presence of hydrogen cyanide; the later molecule could eventually produce amino acids on comets and meteorites through the Strecker route upon aqueous alteration. It is important to note here that the Strecker process could initiate even in the absence of liquid water. Quantum chemical calculations performed by Rimola et al. show that a Strecker-type reaction to form glycine is energetically feasible on solid-water ice grains23. The formation of acetonitrile precursor of glycine on an icy grain mantle via the addition of hydrogen cyanide (HCN) to a dehydrogenated form of aminomethanol has also been shown through calculations49. The present experimental study supports the theoretical investigations23,49 that have demonstrated the involvement of aminomethanol in Strecker synthesis of glycine in astrophysical environments. The current research also conclusively shows that the amines could represent textbook candidates for the Strecker synthesis of amino acids via the formation of aminoalcohols in the prebiotic soup on Earth and in deep space.

Methods

Experimental

Experiments were conducted in an ultrahigh vacuum chamber evacuated to a base pressure of 9 ± 1 × 10−11 torr using turbo molecular pumps backed by a dry scroll pump (Supplementary Fig. 1)24,25. To prepare each ice mixture, gases of methylamine (CH3NH2; 99.95% Matheson TriGas) and oxygen molecule (O2; 99.99% Sigma Aldrich) were premixed and deposited via a glass capillary array onto a silver substrate at an angle of 20° with respect to the normal of the substrate. The silver substrate is mounted on a cold finger made from oxygen-free high conductivity copper. The temperature of the cold finger was maintained at 5.0 ± 0.2 K using a closed cycle helium refrigerator during deposition of the gases. The thickness of each ice (dt; nm) was monitored online and in situ via laser interferometry. In this method, a He-Ne laser of 632.8 nm wavelength (λ) has been used at an angle of incidence (θ) equal to 4° to measure the interference pattern formed after reflection of the laser light from the silver substrate and ice surface. One interference fringe (m = 1) was observed during the deposition of the ice. The average refractive index of the ice mixture (nice = 1.32) was determined from the refractive indices of the neat oxygen (n = 1.25)50 and methylamine ices (n = 1.40)35 reported in the literature. The thickness of the ice mixture was determined to be 239 ± 24 nm using equation (3) provided in the Supplementary Methods. The infrared spectra of the ice mixtures were collected in the 4000–700 cm−1 region using a Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometer (Nicolet 6700) operated at a resolution of 4 cm−1 in an absorption-reflection-absorption mode with an incidence angle of 45° (Supplementary Fig. 2). The ratio of oxygen molecule (O2) to methylamine (CH3NH2) in the ice mixture was found to be 9.2 ± 1.0: 1, based on the column densities (N; molecules cm−2) of O2 and CH3NH2 (Supplementary Methods). Thereafter, each ice mixture was exposed to 5 keV energetic electrons at an electron current of 100 ± 10 nA for 60 min. IR spectra of the ices were measured in situ during irradiation to monitor the changes induced by ionizing radiation. Astrophysical ices experience high energy radiations i.e. UV photons and cosmic-charged particles. The galactic cosmic ray field consists predominantly of protons with distribution maximum of about 10 MeV and losses 99.9 % of their kinetic energy to the electron system of the target molecules51. This electronic energy transfer generates energetic electrons (δ-electrons), which could penetrate into the ice up to a few hundred nanometers and initiate bond rupture processes in the molecular species of the ice mixture via inelastic energy transfer. In this experiment, we have used 5 keV electrons to mimic the effects of δ-electrons. The linear electron energy transfer of MeV protons to the ice target holds a similar value as the 5 keV electrons51,52. Thus, our experiments simulate the formation of aminomethanol in the ice mixture of methylamine and oxygen via charged particles through electronic energy transfer. Using Monte Carlo simulations via CASINO 2.42 software53, the average energy dose was calculated to be 18.3 ± 2.0 eV molecule−1 for methylamine and 18.9 ± 2.3 eV molecule−1 for oxygen (Supplementary Table 1). Hereafter, ices were annealed at a rate of 1 K min−1, and molecules subliming from the substrate were ionized and detected using photoionization along with reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometry (PI-ReTOF-MS). Pulsed VUV light is utilized for the photoionization of the molecules. Two VUV energies at 9.50 and 9.10 eV were used to identify the isomers (Supplementary Table 3). The ions formed are extracted and eventually separated based on their mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio before reaching to microchannel plate (MCP) detector. The MCP detector generates a signal when ions reach to the detector. This signal is amplified using a preamplifier (Ortec 9305) and shaped with a 100 MHz discriminator. The discriminator sends the signal to a computer based multichannel scaler, which records the signal in 4 ns bins triggered at 30 Hz by a pulse delay generator. 3600 sweeps were collected for each mass spectrum per 1 K increase in the temperature during the TPD phase.

Computational

We have employed the density functional theory (DFT) B3LYP/aug-cc-pVTZ geometry optimizations and subsequent harmonic zero-point vibrational energy (ZPVE) corrections from the Gaussian16 program54 with coupled cluster singles, doubles, and perturbative triples [CCSD(T)] aug-cc-pVTZ and aug-cc-pVQZ55,56 single-point energies extrapolated to the complete basis set (CBS) limit via a two-point formula57 in the MOLPRO 2019.2 quantum chemistry program58. The higher-level of theory (utilized for comparison) exclusively employs CCSD(T) and MOLPRO where the geometries are optimized and harmonic frequencies (along with ZPVEs) computed with the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set. At these geometries, CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVQZ single-point energies are computed and the same two-point extrapolation scheme is employed to provide the adiabatic ionization energies and relative energies. All radical cations make use of restricted open-shell Hartree Fock reference wavefunctions, and all neutrals employ fully restricted Hartree Fock references. The transition state optimized geometries and harmonic frequencies are computed with MP2 theory and the aug-cc-pVTZ basis set within Gaussian16 where subsequent CCSD(T)/aug-cc-pVTZ and aug-cc-pVQZ single-point energies are extrapolated to the CBS limit in the same fashion as that done in the other cases.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the main Article, Supplementary Information, and Supplementary Data files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Strecker, A. Ueber die künstliche Bildung der Milchsäure und einen neuen, dem Glycocoll homologen Körper. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 75, 27–45 (1850).

Moutou, G. et al. Equilibrium of α-aminoacetonitrile formation from formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide and ammonia in aqueous solution: Industrial and prebiotic significance. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 8, 721–730 (1995).

Gröger, H. Catalytic enantioselective strecker reactions and analogous syntheses. Chem. Rev. 103, 2795–2828 (2003).

Nájera, C. & Sansano, J. M. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of α-amino acids. Chem. Rev. 107, 4584–4671 (2007).

Wang, J., Liu, X. & Feng, X. Asymmetric strecker reactions. Chem. Rev. 111, 6947–6983 (2011).

Taillades, J. et al. N-carbamoyl-α-amino acids rather than free α-amino acids formation in the primitive hydrosphere: A novel proposal for the emergence of prebiotic peptides. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 28, 61–77 (1998).

Miller, S. L. A production of amino acids under possible primitive earth conditions. Science 117, 528–529 (1953).

Muñoz Caro, G. M. et al. Amino acids from ultraviolet irradiation of interstellar ice analogues. Nature 416, 403–406 (2002).

Brack, A. From interstellar amino acids to prebiotic catalytic peptides: a review. Chem. Biodivers. 4, 665–679 (2007).

Elsila, J. E., Dworkin, J. P., Bernstein, M. P., Martin, M. P. & Sandford, S. A. Mechanisms of amino acid formation in interstellar ice analogs. Astrophys. J. 660, 911–918 (2007).

Danger, G., Plasson, R. & Pascal, R. Pathways for the formation and evolution of peptides in prebiotic environments. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 5416–5429 (2012).

Thaddeus, P. The prebiotic molecules observed in the interstellar gas. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 361, 1681–1687 (2006).

Cleaves, H. J. The prebiotic geochemistry of formaldehyde. Precambrian Res. 164, 111–118 (2008).

Riffet, V., Frison, G. & Bouchoux, G. Quantum-chemical modeling of the first steps of the strecker synthesis: From the gas-phase to water solvation. J. Phys. Chem. A 122, 1643–1657 (2018).

Nielsen, A. T., Moore, D. W., Ogan, M. D. & Atkins, R. L. Structure and chemistry of the aldehyde ammonias. 3. Formaldehyde-ammonia reaction. 1,3,5-Hexahydrotriazine. J. Org. Chem. 44, 1678–1684 (1979).

Schutte, W. A., Allamandola, L. J. & Sandford, S. A. An experimental study of the organic molecules produced in cometary and interstellar ice analogs by thermal formaldehyde reactions. Icarus 104, 118–137 (1993).

Feldmann, M. T., Widicus, S. L., Blake, G. A. IV, D., R. K. & W., A. G. III Aminomethanol water elimination: Theoretical examination. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 034304 (2005).

Ali, M. A. Theoretical study on the gas phase reaction of CH2O + NH3: the formation of CH2O⋯NH3, NH2CH2OH, or CH2NH + H2O. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 19242–19251 (2019).

Bossa, J. B., Theule, P., Duvernay, F. & Chiavassa, T. NH2CH2OH thermal formation in interstellar ices contribution to the 5-8 μm region toward embedded protostars. Astrophys. J. 707, 1524–1532 (2009).

Hays, B. M. & Widicus Weaver, S. L. Theoretical examination of O(1D) insertion reactions to form methanediol, methoxymethanol, and aminomethanol. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 7142–7148 (2013).

Wolf, M. E., Hoobler, P. R., Turney, J. M. & Schaefer, H. F. Important features of the potential energy surface of the methylamine plus O(1D) reaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 24194–24205 (2019).

Bunn, H. A., Schultz, C. P., Jernigan, C. M. & Widicus Weaver, S. L. Laser-induced chemistry observed during 248 nm vacuum ultraviolet photolysis of an O3 and CH3NH2 Mixture. J. Phys. Chem. A 124, 10838–10848 (2020).

Rimola, A., Sodupe, M. & Ugliengo, P. Deep-space glycine formation via Strecker-type reactions activated by ice water dust mantles. A computational approach. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 12, 5285–5294 (2010).

Bennett, C. J. et al. High-sensitivity Raman spectrometer to study pristine and irradiated interstellar ice analogs. Anal. Chem. 85, 5659–5665 (2013).

Jones, B. M. & Kaiser, R. I. Application of reflectron time-of-flight mass spectroscopy in the analysis of astrophysically relevant ices exposed to ionization radiation: Methane (CH4) and D4-methane (CD4) as a case study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 1965–1971 (2013).

Zhu, C. et al. The elusive cyclotriphosphazene molecule and its Dewar benzene–type valence isomer (P3N3). Sci. Adv. 6, eaba6934 (2020).

Turner, A. M. & Kaiser, R. I. Exploiting photoionization reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometry to explore molecular mass growth processes to complex organic molecules in interstellar and solar system ice analogs. Acc. Chem. Res. 53, 2791–2805 (2020).

Abplanalp, M. J. et al. A study of interstellar aldehydes and enols as tracers of a cosmic ray-driven nonequilibrium synthesis of complex organic molecules. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 7727–7732 (2016).

Kleimeier, N. F., Eckhardt, A. K., Schreiner, P. R. & Kaiser, R. I. Interstellar formation of biorelevant pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH). Chem 6, 3385–3395 (2020).

Singh, S. K. et al. Identification of elusive keto and enol intermediates in the photolysis of 1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazinane. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12, 6062–6069 (2021).

Turner, A. M., Chandra, S., Fortenberry, R. C. & Kaiser, R. I. A photoionization reflectron time-of-flight mass spectrometric study on the detection of ethynamine (HCCNH2) and 2H-azirine (c-H2CCHN). ChemPhysChem 22, 985–994 (2021).

Bergantini, A. et al. A combined experimental and theoretical study on the formation of interstellar propylene oxide (CH3CHCH2O)—a chiral molecule. Astrophys. J. 860, 108 (2018).

Zhu, C. et al. A vacuum ultraviolet photoionization study on the formation of methanimine (CH2NH) and ethylenediamine (NH2CH2CH2NH2) in low temperature interstellar model ices exposed to ionizing radiation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 1952–1962 (2019).

Cosby, P. C. Electron‐impact dissociation of oxygen. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 9560–9569 (1993).

Frigge, R. et al. A vacuum ultraviolet photoionization study on the formation of N-methyl formamide (HCONHCH3) in deep space: A potential interstellar molecule with a peptide bond. Astrophys. J. 862, 84 (2018).

Fourikis, N., Takagi, K. & Morimoto, M. Detection of interstellar methylamine by its 202→110 Aα state transition. Astrophys. J. 191, L139 (1974).

Kaifu, N., Takagi, K. & Kojima, T. Excitation of interstellar methylamine. Astrophys. J. 198, L85 (1975).

Goesmann, F. et al. Organic compounds on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko revealed by COSAC mass spectrometry. Science 349, aab0689 (2015).

Parker, E. T. et al. Primordial synthesis of amines and amino acids in a 1958 Miller H2S-rich spark discharge experiment. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108, 5526–5531 (2011).

Altwegg, K. et al. Prebiotic chemicals—amino acid and phosphorus—in the coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600285 (2016).

Glavin, D. P., Dworkin, J. P. & Sandford, S. A. Detection of cometary amines in samples returned by Stardust. Meteorit. Planet Sci. 43, 399–413 (2008).

Förstel, M., Bergantini, A., Maksyutenko, P., Góbi, S. & Kaiser, R. I. Formation of methylamine and ethylamine in extraterrestrial ices and their role as fundamental building blocks of proteinogenicα-amino acids. Astrophys. J. 845, 83 (2017).

Gürtler, J. et al. Detection of solid ammonia, methanol, and methane with ISOPHOT*. Astron. Astrophys. 390, 1075–1087 (2002).

Holtom, P. D., Bennett, C. J., Osamura, Y., Mason, N. J. & Kaiser, R. I. A combined experimental and theoretical study on the formation of the amino acid glycine (NH2CH2COOH) and its isomer (CH3NHCOOH) in extraterrestrial ices. Astrophys. J. 626, 940–952 (2005).

Larsson, B. et al. Molecular oxygen in the ρ Ophiuchi cloud. AA 466, 999–1003 (2007).

Du, F., Parise, B. & Bergman, P. Production of interstellar hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) on the surface of dust grains. Astron.Astrophys. 538, A91 (2012).

Bergner, J. B., Öberg, K. I. & Rajappan, M. Methanol formation via oxygen insertion chemistry in ices. Astrophys. J. 845, 29 (2017).

Danger, G., Duvernay, F., Theulé, P., Borget, F. & Chiavassa, T. Hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN) formation in astrophysical conditions. Competition with the aminomethanol, a glycine precursor. Astrophys. J. 756, 11 (2012).

Koch, D. M., Toubin, C., Peslherbe, G. H. & Hynes, J. T. A theoretical study of the formation of the aminoacetonitrile precursor of glycine on icy grain mantles in the interstellar medium. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 2972–2980 (2008).

Hudgins, D. M., Sandford, S. A., Allamandola, L. J. & Tielens, A. G. G. M. Mid- and far-infrared spectroscopy of ices: optical constants and integrated absorbances. Astrophys. J., Suppl. Ser. 86, 713 (1993).

Bennett, C. J., Jamieson, C. S., Osamura, Y. & Kaiser, R. I. A Combined experimental and computational investigation on the synthesis of acetaldehyde [CH3CHO(X1A′)] in interstellar ices. Astrophys. J. 624, 1097–1115 (2005).

Johnson, R. E. Energetic Charged-Particle Interactions with Atmospheres and Surfaces (Springer, 1990).

Drouin, D. et al. CASINO V2.42—A fast and easy-to-use modeling tool for scanning electron microscopy and microanalysis users. Scanning 29, 92–101 (2007).

Frisch, M. J. T. et al. Gaussian 16 Revision C.01 (Gaussian, Inc., 2016).

Raghavachari, K., Trucks, G. W., Pople, J. A. & Head-Gordon, M. A fifth-order perturbation comparison of electron correlation theories. Chem. Phys. Lett. 157, 479–483 (1989).

Dunning, T. H. Gaussian basis sets for use in correlated molecular calculations. I. The atoms boron through neon and hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 90, 1007–1023 (1989).

Martin, J. M. L. & Lee, T. J. The atomization energy and proton affinity of NH3. An ab initio calibration study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 258, 136–143 (1996).

Werner, H.-J. et al. Molpro: a general-purpose quantum chemistry program package. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2, 242–253 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US National Science Foundation, Division of Astronomical Sciences under grants AST-1800975 and AST-2103269 awarded to the University of Hawaii. R.C.F. acknowledges support from NASA grant NNX17AH15G, startup funds provided by the University of Mississippi, and computational support from the Mississippi Center for Supercomputing. Research funded in part by NSF Grants CHE-CHE-1338056 and OIA-1757220.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.I.K. and S.K.S. designed the experiments. S.K.S., C.Z. and J.L.J. performed the experiments. R.C.F. performed the calculations. S.K.S. and R.I.K. wrote the manuscript, which was revised and approved by all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, S.K., Zhu, C., La Jeunesse, J. et al. Experimental identification of aminomethanol (NH2CH2OH)—the key intermediate in the Strecker Synthesis. Nat Commun 13, 375 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27963-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-022-27963-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.