Abstract

Since the late 19th century, genital modifications (female and male) have been an important research subject in anthropology. According to a comparative and constructivist perspective, they were first interpreted as rites of passage, then as rites of institutions. In a complex dialogue with feminist movements, 20th-century scholars recognised that the cultural meanings of these modifications are multiple and changing in time and space. Conversely, according to WHO, since the 1950s, Female Genital Mutilation or Cutting (FGM/C) has been considered a form of Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG). Interpreted as VAWG, FGM/C has progressively been isolated from its complementary male rite, selected for special condemnation, and banned. An order of discourse has been built by WHO and other international organisations. This article provides a genealogic deconstruction of the order of discourse lexicon, highlighting dislocations between anthropology and the human rights agenda. Today, genital modifications encompass FGM/C, male circumcision, clitoral reconstruction after FGM/C, gender reassignment surgery, and intersex and ‘cosmetic’ genital surgery. I propose to call these procedures Gendered Genital Modifications (GGMo). GGMo implicates public health, well-being, potential harm, sexuality, moral and social norms, gender empowerment, gender violence, and prohibitive and permissive policies and laws. The selective production of knowledge on FGM/C has reinforced the social and political polarisation between practices labelled as barbaric and others considered modern, accessible, and empowering. I suggest an anthropological interpretation for the socio-cultural meanings of health, sexuality, purity and beauty. I propose future interdisciplinary studies of how consent, bodily integrity and personal autonomy bear on concepts of agency and subjectivity in the sex/gender system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the late 19th century, the genital modification of females (through excision/clitoridectomy [1], infibulation [2]/pharaonic circumcision [3], introcision [4], labia elongation [5] and ritual defloration/dilatatio vaginae [6]) and males (through circumcision [7], subincision [8] including artificial hypospadias [9], excision of the testicle [10] and ritual castration [11]) has been an important research subject in cultural anthropology [12,13,14]. From a comparative and constructivist perspective, classical ethnography (i.e. the inductive method of long-term participant observation) considered these operations, which were conducted in many non-European contexts (e.g. in Africa, Oceania including Australia, and Southeast Asia including Thailand and Indonesia), to be initiation rites; specifically, they were seen as rites of passage [15], marking and facilitating the transition from childhood into adulthood [16, 17].

Early ethnographies provided accurate descriptions of how these rites (individual or collective) were carried out, highlighting ages, procedures, tools and ritual operators. According to this vision, genital modifications were also interpreted as bodily techniques [18] through which actors and societies reshaped the natural human figure to mark people’s social belonging. The irreversible cutting of the flesh was read as a ‘sign on the body’ and transformed the individual into an accepted member of certain religious and ethnic communities. Removing what is considered, from a social perspective, to be impure, unaesthetic and morally troubling helped individuals perceive themselves as approved, socially recognised women and men [19].

Since the mid-20th-century scholars recognised that the cultural meanings of genital modifications are multiple and changing in time and space. In a complex dialogue with feminist movements [20, 21], scholars explained the symbolic meanings of genital modifications: depending on the group, the context, and the type of modification, the meanings could include attempted preservation of a girl’s virginity prior to marriage, perception of increased fertility, increase or decrease in sexual pleasure, multiple levels of purity, protection against an alleged excess of sexual desire (whether in females or males), hygiene of the genital organs, elevation of status conferring respect required for marriageability and other gendered cultural values [22,23,24,25,26,27]. The anthropological perspective used to study the local cultural frame (i.e., emic vision) focused on the processes that society enacted on the bodies of individuals; this led to the acknowledgement that it is not only adulthood but also gender roles/norms that are socially instituted [28,29,30] by the cutting [31] or manipulation of genital tissues [32].

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the main UN agencies have defined female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C) as ‘all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons’ [33]. Because genital modification was not only salient to anthropologists, but also to political actors of various sorts, a Foucauldian ‘order of discourse’Footnote 1 was built around FGM/C and this has become hegemonic in the global human rights system (see Appendix 1). Indeed, since the 1950s and through the ongoing enforcement of the human rights agenda, female genital modification has become the object of strong public and political debate.

From an anthropological perspective [34], as informed by the understandings of practising societies, female and male genital modification rituals were seen as symbolically linked [35], complementary practices within a sex/gender system (understood as the cultural processes by which sex, in a biological sense, is transformed into a gender as a social productFootnote 2 [36]): both practices worked together to support, reinforce, and reproduce gendered relations in accordance with the prevailing norms of the local culture [37] (often local names are the same for the female and male rite). Moreover, these gender roles or norms were not necessarily organised around a hierarchical principle of female oppression and subordination; rather, prescriptive norms for men and women have varied widely across practising cultures, with power or status hierarchies often operating over age, for example, more than sex or gender per se. Such norms have undergone considerable transformation—and homogenisation—in certain societies as a consequence of the “colonial situation” [38, 39]; nevertheless, the value or status associated with male or female gender roles in contemporary settings continues to vary along multiple axes across different social domains (e.g. ethnicity), both within and between societies that practise genital modification (e.g. class). Bodily and sexual techniques are gendered incorporation processes and become a sphere of negotiation of social relationships between and inside genders and generations [40]. Thus, it is an oversimplification to assume that, wherever male and female ritual genital modifications occur, the female ritual is primarily oriented around socialising girls into a subordinate role [41].

Nevertheless, international actors opposed to female (but not male) genital modification have tended to ignore the male rites within practising societies while interpreting the female rites within the same societies in a highly reductive manner: as sex-discriminatory institutions of violence against women and girls (VAWG). Based on this interpretation, FGM/C began to be isolated: geographically, with a focus on African female genital modifications (ignoring Western-associated modifications, such as female ‘cosmetic’ labiaplasty or genital piercing); scientifically, with almost all subsequent research oriented around documenting harms as well as methods for elimination; politically, with opposition to FGM/C becoming a requirement for Western funding and favour; and anthropologically, becoming conceptually divorced from the parallel male rites occurring within the same sex/gender systems. The female rites also became re-defined (as barbaric mutilations), selected (placed into special typologies) and legally banned. This now so-called “female genital mutilation” or “FGM” became associated with irrationality, misogyny, primitiveness and serious harm.

At the same time, contemporary anthropological perspectives continue to stress and investigate the controversies (e.g. about preconceived Western ideas on genital modification and its origins, the importance of cultural relativism, the analysis of patriarchy as a Western inheritance, the recognition of the women’s social status, etc.) [42], projected cultural histories [43], impacts of colonialism [39], contested definitions [44] and terminologies [45], changes in paradigms [46], humanitarian reasons and moral economies [47], new postures (e.g. the modification as female empowerment) [48], and possible dialogues between different disciplines and movements [49]. Ignoring much of this research, the WHO has persisted in cordoning off and defining only non-Western-associated female-only genital modification as a grave human rights abuse, except when performed for ‘medical reasons’. Much of the academic literature, journalistic coverage of the topic, and international policy and law approaches to genital modification have taken their cue from the WHO.

However, a social change is now blurring this boundary. Questions are now increasingly raised about practices that have been biomedicalised in the West. In recent decades, various gendering surgeries have contributed to the biomedical construction of gender, often interpreted as new, technologically sophisticated, ‘liberal’ forms of genital modification. Gender reassignment surgery (GRS) and genital cosmetic surgery (GCS) emerged as ways to refashion one’s anatomy so that it is in line with one’s gendered and sexual preferences, desires [50] and identity needs. In the neoliberal framework, these surgeries are generally associated with health, modernity and empowerment. Further, intersex surgery (IS) [51, 52], primarily performed on infants and small children, is lauded by medical professionals as a modern ‘solution’ to sexually ambiguous genitalia; whereas, activists opposed non-consensual IS have identified it as intersex genital mutilation (IGM) [53]. Finally, male circumcision (MC), historically understood to be a ritual practice, has also undergone a biomedical transformation in the West: it is increasingly, albeit controversially, touted as a means of prophylaxis against infections and disease (so-called voluntary medical male circumcision or VMMC) [54]; meanwhile, activists who oppose the practice when performed on non-consenting individuals sometimes call it male genital mutilation (MGM).

Although these operations have all been constructed as being categorically distinct from FGM/C, they do share certain features with it that require consideration: they remove tissue from or otherwise modify a health vulva or penis and, when performed on infants or children, they raise ethical challenges concerning consent [55], autonomy [56, 57] and notions of bodily integrity [58]. As a way of resisting such uncomfortable comparisons, however, opposite imaginary constructs have emerged: ‘liberated bodies’ (Us) versus ‘victim bodies’ (Others). The deconstruction of these categories is necessary [59]. Going forward, it will be essential to know how, why and when genital modifications constitute a violation of a person or a form of gender oppression as well as when it becomes a gendered right. As new discourses [60] on the inviolability of one’s genitals arise and call into question state biopolitics, such questions will gain fundamental relevance in contemporary societies.

This article aims to provide a genealogic deconstruction of the genital modification lexicon, focusing on fractures and dislocations between anthropological perspectives and global human rights policies. Regarding female genital modifications, I argue that the ‘FGM/C’ order of discourse has produced a real ‘heterogony of ends’ (a process whereby original motivational intentions become modified through a chain of events). I also highlight the uses and abuses of anthropological vocabulary. Finally, I suggest a new interdisciplinary method based on gendered ethnography (as a political critique) to analyse all genital modification practices. This method allows for providing due attention to the intersubjectivity of social actors and researchers as well as management of gender-power-related tensions that could arise in the field; it aims to produce knowledge that may contribute to scientific and non-scientific fields [61]. Paraphrasing Butler, ethnographic fieldwork is the way to yield to another’s experience, dignify the words of both social actors and the researchers involved, and to grasp the meaning of life practices in a constant intercultural dialogue [62].

The genealogy of FGM/C’s order of discourse

Since colonial times, genital modification has been the subject of politics and policies. As an illustration of this, we will remember the colonial dispute between British Christian missionaries and the Kikuyu, a Kenyan ethnic group, regarding the colonial ban on female ‘circumcision’ [63]. On the one hand, this colonial decision was met with tumult and a major boycott of mission schools and churches by members of the Kikuyu; on the other hand, it served as a cause to rally African support for Kikuyu political leaders. One of the consequences was the birth of independent schools and churches as a form of autonomy from British domination [64].

Since the end of the Second World War, the issue of female genital modification has become a problem in the global North; this is because it fits into the discourse of human rights and the birth of major international organisations as outlined in the vision of the Universal Declaration of 1948 and in the Geneva Conference of the Society for the Protection of Children (1948) [65].

One year earlier, in 1947, the Executive Board of the American Anthropological Association (AAA) prepared a statement on human rights and submitted it to the UN Commission on Human Rights. Briefly, the AAA critiqued what they saw as an ethnocentric position (i.e., the belief in the superiority of one’s own culture or ethnic group) endorsed by the UN, instead proposing to centre cultural diversity through the concept of cultural relativism: roughly, the belief that certain values, instantiated in practices, may be relative to specific cultures and should therefore not be denigrated simply on the grounds that they do not conform to one’s own cultural standards.

The AAA’s statement, which was based on this notion of cultural relativism and the belief that no substantive declaration of rights could be meaningfully applied to all human beings irrespective of their cultural context [66], marked a hiatus of a productive dialogue between anthropology and international conventions concerning human rights. We can call this period ‘the birth of the order of discourse,’ [67] and it can also be understood from the attitude of the UN agencies and as defined in several conferences (see Appendix 1).

In 1958, the UN Economic and Social Council asked the WHO ‘to undertake an inquiry into the persistence of these practices (meaning female genital modifications) and into measures adopted or planned to stop the ritual operations’ [68]. In 1959, the WHO answered that ‘the ritual practices in question resulting from social and cultural conceptions are not within WHO’s jurisdiction’ [69]. In other words, at first, the WHO had declined the invitation. Yet, in its resolution 821 II (XXXII), which was adopted in 1961, the UN Economic and Social Council again invited the WHO to study at least the medical aspects of the female-affecting operations based on custom. For almost a decade (the 1960s-70s), the WHO and other international organisations, such as UNICEF, saw the FGM/C as a cultural problem (and not a public health one); they assumed that it needed to be analysed (e.g., data collection) and resolved by the local politics of the countries involved. As a result, probably, for this reason, WHO did not respond to the UN Economic and Social Council.

But it is in this same period, from a descriptive and interpretative view of cultural complexity (as evidenced by ethnography), we saw a dislocation of meaning within the notions of culture, ritual operations, and tradition, which are the basis of anthropological knowledge. They acquired political value and became descriptive notions in the sense of classification: Us and the Others. These anthropological concepts were considered using an ahistorical and essentialist perspective: ‘seemingly universal essentialist generalisations about “all women” are replaced by culture-specific essentialist generalisations that depend on totalising categories such as “Western culture,” “Non-western cultures,” “Western women,” “Third World women”’ [70] and so on. Some cultural practices were conceptualised as harmful only for specific categories of human beings: women and girls (i.e. minorities to be protected). Despite the allure ‘of such grand metanarratives, gender essentialism produces a theory that effaces the differences between women’ [71] both within and between cultural contexts or societies. In this victimisation rhetoric only women and girls who live in contexts conceptualised as barbaric (e.g., Africa), where operations of this kind take place for cultural reasons, need to be saved.

To international organisations, anthropology seemed to be the most appropriate discipline to draw on, because it studies cultural diversity (the Others). The nascent theories of social change (i.e., consideration of human relations as interactions shaped over time) and cultural pluralism were not functional for the purpose of political discourse. The only targeted concept was the culture (understood in a primitive and essentialist significance, as barbaric tradition), which was considered the basis of violence against women. In the anthropological sense, the culture is a symbolic system integrated, shared and dynamic, something we acquire during all our lives.

It is no coincidence that, in addition to genital practices, other cultural practices (e.g., child marriage, female infanticide, menstrual stigma and nutritional practices) were considered by UN agencies as a type of social pressure through which men oppress women via patriarchy. This is a concept that feminist anthropology has intensely criticised when it is assumed in an ahistorical sense; it is believed that all men (men as a class or category) prevent women from freely expressing themselves or (otherwise) exercising agency, and, consequently, men become the silencers of women. In this rhetoric, women in the Global South emerge as victims to be saved because they are represented as uneducated, unlettered, custom-bound, oppressed, domesticated and forever victimised [72]. The body is a place where men reinforce their strength (note: also through male circumcision) by weakening the female body with ‘harmful traditional practices’ [73]. The harm is the expression of violence, which is carried out directly on the body, sexuality and, finally, on health; this is especially true for African women, a category that is an abstraction/invention from the anthropological point of view. African women’s bodies will be interpreted as symbols of oppression at the hand of barbaric and uncivilised practices, and their sexuality will be compromised. (see Box 1).

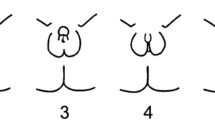

Based upon this framework, the operations that had been defined in 1967 as ‘male genital mutilation’ by anthropologist George Peter Murdock [74] were expelled from the order of discourse because they were not seen as instances of violence against women nor as adversely affecting health (that is, setting aside ‘botched’ operations; male sexual health was thus conceptualised in a heteronormative and reductive sense as the capacity for erection and ejaculation/orgasm, so as to potentially impregnate a female partner; the sexual sensations and affordances of the foreskin itself are erased on this conception). At the same time, the female operations—still sometimes called ‘female circumcision’ but increasingly ‘FGM’ – were isolated geographically (imagined to be quintessentially “African”), and defined and classified by the WHO into four typologies (roughly: type 1 – modifications of the clitoris; type 2 – modifications of the labia; type 3 – infibulation; type 4 – miscellaneous); meanwhile ritual defloration and ritual dilatation (i.e., widening of the vaginal orifice) ceased to be matters of concern. This order of discourse was consolidated in the 1970s; these were the years characterised by second-wave feminism and, among other things, the idea of global solidarity of women. Specifically, the task of women living in the North of the world was to save women in the South. The body was the pivotal point of the discussion because it became a politically oriented project of self-determination. The slogan ‘personal is political’ worked well in the discourse to denounce female genital modifications.

The years leading on from the 1970s and into the 1980s became a turning point for the consolidation process of the formula ‘Female Genital Mutilation’ in a political sense. On the academic front, Rose Hayes, for the first time, used the expression ‘female genital mutilation’ to describe the cultural/functional/structural complexity of infibulation in the Sudan [75]. That article remains one of the most interesting interpretative texts of the period, as it is based on rich fieldwork in which anthropological instruments were used to clarify that the ‘mutilation’ was only part of a more comprehensive ritual apparatus. Regarding genital modifications, analysis showed that the deconstruction of the physical body involves a ‘construction’ of the symbolic one within the sex/gender system (the relationships/hierarchies both of gender, male and female; and of generations, between older and younger women). Concepts like multi-gender positioning (i.e., taking multiple or different gendered positions during life) [76] and subjectivity (i.e., a specific cultural and historical consciousness existing at the individual and collective level)Footnote 3 [77, 78], had started to develop in feminist ethnography but did not seem entirely useful for political purposes of the female genital modification discourse. However, the expression ‘FGM’, which reflects the assumptions of the international agenda and framework for elimination of the female rites, provided an explicit condemnation and denunciation of what was conceptualised as a ‘harmful traditional practice’ where traditional became synonymous of violent and savage. It also provided an implicit ‘condemnation’ of the anthropological discipline that advanced alternative or neutral terminologies (e.g., circumcision/circumcision of girls, female genital cutting, female genital modificationFootnote 4 female genital alteration, female genital surgery and local terms) [79].

The adoption of the acronym ‘FGM’ took place in the political arena through the contributions of one of the most influential but ambiguous figures [80] of the period: Franziska Porges Hosken, also known as Fran Hosken. Hosken, born to a Jewish family in Vienna (her father was a physician) and later immigrating to the United States at the age of 18 in 1938, was a designer (with a degree in architecture), writer/journalist, photographer and, later, adviser to WHO and representative of Western feminism [81]. She didn’t coin the term ‘FGM’ - as often claimed - but she did use the term to politicise the issue in 1976 [82] and then in 1979 in the context of the first large-scale survey on the subject. The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females. Hosken presented on this survey at the WHO’s Seminar on traditional practices affecting the health of women and children in Khartoum. This report was used as a textbook for years. Hosken herself condemned both female genitals cutting and the very discipline of anthropology because, at the time, most anthropologists were men and, according to her, ‘naturally’ embodied power, and domination. It was certainly not a coincidence that the topic of ‘FGM’ became a ‘separate subject’ of sorts studied primarily by (and for) women researchers and feminists.

During the 3rd UN World Conference on Women in Nairobi (1985), the concept of gender mainstreaming was introduced. In principle, gender mainstreaming (as a strategy for promoting gender equality) and empowerment (the process by which women gain power and control over their own lives and acquire the ability to make strategic choices) should have been positive concepts; however, both concepts became the passe-partout of global hegemonic differentialist politics. Some scholars illuminated how, because they represent a Western idea projected onto the Other’s social relations and sex/gender systems, these definitions are ambiguous and polymorphic. For example, the concept of gender mainstreaming refers to many different things (e.g., access to technology or gender equality in parliament). Further, the idea of empowerment implies that an external authority gives power to women, and those women are often wealthy, with their own agendas and preconceptions, which diminishes poor women’s agency [83].

Through these and other developments, the FGM vocabulary became solidified despite local mistrust, conflicts of interest, and other controversies, seen in large part as a medical (i.e., women’s health) issue until the 1990s. The order of discourse then became a hegemonic act of humanitarian reason, which indicates that the introduction and promotion of moral sentiments into human affairs become the essential element of contemporary local and global policies [84]. This posture, which is compassionate and repressive at the same time, authorised the criminalisation of FGM/C. Consider, for example, the 4th World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995) (see Appendix 1) [85]. The 1990s were years of paradigmatic change ‘from health to human rights’ [46], and then a combination of the two [86], and saw significant criticism about politics of interference by the post- and de-colonial feminist movements.Footnote 5 FGM/C became the focus of global debates on VAWG, gender-based violence (GBV) and reproductive rights. Despite the diffidence exhibited by some feminist anthropologists [88, 89], FGM’s definition (i.e., a formula that excludes and homogenises operations that do not include an actual cut; see Box 2) is followed by a politics of naming and classification [87].

As a result, these ‘imperfect glossaries’ based on ahistorical notions (e.g., notions of ‘culture’, ‘tradition’, ‘potential victims’, ‘victims at risk’, ‘harmful traditional practices’, ‘social pressure’ and ‘for non-therapeutic purposes’) have been locally incorporated and become part of the vernacular. The process of vernacularisation ‘is one of appropriation and translation. Human rights ideas and feminist ideas are appropriated by national elites and middle-level social activists and translated into local terms’ [90]. As some studies have shown, the real effects of such appropriation/translation in the field can be profound [91] (e.g. the impact of African women reformist elites and the developmentalist colonial state on the experience of girlhood in Nigeria, as demonstrated by George Abosede [92]; or the problematic incorporation of gender mainstreaming in the humanitarian discourse on gukuna, a Rwandan genital manipulation [93]) (see Box 2 for discussion).

Despite their shortcomings, these glossaries became the frame of reference, not only for many academics and medical researchers, but also within international organisations, NGOs, local legislation and governments (see Box 3).

This vocabulary was also legitimised across interactions between moral economies and the seduction of quantification [94] and allowed FGM to be conclusively positioned within the framework of its criminalisation. Contemporary moral economies characterise a specific historical moment and, sometimes, a particular group (e.g., minorities, such as migrants, refugees, women). By analysing the moral economy, we consent to understanding ‘the production, dissemination, circulation, and use of emotions and values, norms and obligations in the social space’ [95]. The representation of suffering (e.g., through ‘shocking’ or graphic images and narratives, whereby the most extreme, non-representative outcomes are used to illustrate, or stand in for, the entire class of procedures/effects) has become increasingly commonplace in the public sphere, including on social media and in the political arena, and it has defined the strategies of (bio)power to justify action. Utilising the imperfect vocabulary, FGM has been defined historically as a ‘pressure norm’ (i.e., a violation of individual and collective rights of women in the global South), resulting in its condemnation. On the other hand, for example, aesthetic surgery has been framed as a ‘social norm’ and legitimised as an expression of freedom of choice among Western women.

Consider an example of such conflicting interpretations. Eugenia Kaw argues in her ethnography that, in the US, the demand for cosmetic surgery to be performed on Asian American women’s ‘racial traits’ is intensified by stigma experienced by racialised minorities in a white-dominated society [96]. According to her interpretation, Western culture has progressively produced the idea that Asian facial features are synonymous with an emotionless and pallid expression. Korean women feel inadequate and have internalised the ‘self-racism subtext,’ then request surgery to distance themselves from these negative features and avoid being viewed as passive subjects lacking in sociability. In this framework, where cosmetic surgery is presented as a form of empowerment and freedom of choice, cosmetic surgeons become the ‘producers of the norm’ and contribute to the process of ‘acceptance’ and social homogenisation. The choice of surgery, more than a transformation (i.e., ‘beautification’ in the aesthetic surgery vocabulary), is a process of gender normalisation conforming to Western/white definitions of femininity and beauty.

At the same time, cosmetic surgery in the neoliberal era seems to provide social and economic mobility as a synonym for success, which explains its contemporary popularisation and normalisation. This example illuminates the ‘paradox of choice’ (i.e., circumstances that leave social actors, especially women, without real options, as shown by Kathryn Morgan) [97]. Morgan identifies three paradoxes: the choice of conformity (i.e., replacement of minority identity with white conformity), the liberation into colonisation (i.e., voluntary mutilation to create a new accepted body; the body is seen as a raw material to be shaped to fit external standard—the white one), coerced voluntariness and the technological imperative (i.e., social pressure, such as that experienced through exposure to social media and advertising, to achieve perfection of femininity through technology). This is a useful concept for understanding also whether gendered surgery is liberating or coercive.

Returning to FGM/C, according to UNICEF, ‘more than 200 million girls and women alive today have been subjected to the practice, according to data from 30 countries where population data exist’ [98]; this prevalence estimate forms the basis of the discourse that views FGM as a form of GBV. According to Merry, such quantification is seductive because it offers numerical information to describe, compare and rank different things (e.g., jobs, schools, aesthetic surgery, gender violence). This consolidated ‘indicator culture’ shapes neoliberal governance on a local and global level. On the one hand, the indicators draw on subjective data about social phenomena, quantify it, and present it as true and objective. On the other hand, the numbers silence social actors, such as the feminist movements of the Global South. The indicators simplify complex local and social dynamics. The quantification can be risky because what is calculated and represented also influences the common sense of what needs to change and how to do it [94].

Because the FGM discourse has been incorporated locally, moral economies and quantitative measurements produce social effects that must be critically investigated; it is especially important that we investigate their impact on the process of subjection [99] in the double sense of ‘becoming subordinated’ in the sex/gender system as well as ‘becoming a subject’ (also resistance). Both aspects of the process of subjection should be analysed via interdisciplinary and comparative fieldwork (with other/new forms of genital modifications) to help intercultural dialogue.

The new technologies of gender

From an anthropological point of view and out of FGM/C’s order of discourse, I suggest that hymenoplasty [100, 101], labia elongation [93], intimate cosmetic surgery (male [102] and female [103]), clitoral reconstruction [104], male circumcision [105, 106], gender reassignment surgery (GRS) and operations on intersex new-borns [51] should be understood as technologies of gender [107] under a local hierarchical sex/gender system. The distinguishing feature of these practices is that they are concentrated on the sexual anatomy and require ‘surgery’ [108]. GRS, which is widely considered to be an enhancement of trans people’s rights, is increasingly being contested where it is required to gain one’s desired administrative identity. Furthermore, IS and male circumcision are being denounced as mutilation [109] by secular activist movements that defend LGBTQ + rights. Clitoral reconstruction [110], which is sold as surgical ‘repair’ of FGM/C is now offered in several countries, with growing criticism of the practice from various corners.

Conversely, despite multiple laws and prevention projects [111] aimed at ‘eradicating’ it, so-called FGM/C persists in part because of its increasing biomedicalisation in various countries. The FGM/C biomedicalisation, sometimes in local context is perceived as dissolving health risks. Moreover, along with hymenoplasty, which some women seek to restore a cultural marker of supposed virginity, the appeal of Cosmetic Genital Surgery (CGS) is growing rapidly, even for girls under 17 years old.Footnote 6 [112, 113]. These latter practices are being presented in the media and in public discourse as appealing fashion choices (e.g., by being referred to as ‘designer vagina’ [114], ‘barbiplasty’, ‘vaginal rejuvenation’ [115] and the ‘enhancing of sexual life’), and they do not raise public concern [116]. The hegemonic scientific approach (which takes for granted the opposition of customary versus modern, oppression versus freedom, and traditional practice versus surgery) thus produces knowledge by separating these practices [117] and is inadequate in answering new socially relevant questions about freedom or coercion, desire and oppression, etc.

In the realm of development projects and immigration policies [91], some studies have questioned the isolation of FGM/C, arguing that it should be compared to other forms of genital modification, such as male circumcision. Anthropological fieldwork has rarely addressed the recent shifts in meaning regarding male circumcision in the West [34], particularly within the framework of the ‘multicultural dilemma, as a “problem” of minority groups that wish to maintain “ritual” practices for “religious” reasons, which can, subsequently, only be made acceptable throughout medical interventions’ [118]. Consistent with this interpretation, in recent decades, the global public health agenda reframed the cutting of the foreskin as beneficial for the prevention of HIV [119]. Thus, male circumcision is now promoted as a health practice in the countries of the global South, especially in Africa, including contexts where circumcision was not previously practised. Simultaneously, male circumcision is being contested [120] in the global North as a form of gender violence [121].

These changes have been studied from biomedical, juridical and bioethical viewpoints; [122] however, they have not been studied enough from a gendered ethnographic-based perspective, which could clarify how cultural meanings of the body, impurity, sexuality and religion are being reframed. Today, a critical analysis of policies and legislation as well as symbolic, social and biomedical dimensions are fundamental. In other words, a study of the ‘mindful body’ [123], (defined by Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Margaret Lock as an in fieri construction in the interlacement between dynamics of production, reproduction and cultural reinvention) is increasingly necessary.

Medical anthropology suggests three perspectives for understanding the mindful body: the individual body (lived experience), the social body (as symbol), and the body politic (referring to the regulation, surveillance, and control of reproduction and sexuality in work, etc.). The selective legislation regarding genital modification (e.g., medically unnecessary female, but not male or intersex, child genital cutting being prohibited) places a higher value on the political body (e.g., in reproducing gendered norms around victimhood) than the other two dimensions. For these reasons, it is crucial to rebalance the approach, redistributing the importance of the three dimensions. It is fundamental to ethnographically examine the individual and social dimensions of genitalia and to historically situate the prejudicial production of the political dimension.

It is also required that we investigate how—through the biomedicalisation of genital modification—the social dimension articulates with the individual one. The first dimension focuses on issues regarding gender binarism, purity and health, while the second focuses on the lived experience of harm/violence and/or empowerment as outcomes of the procedures. It is crucial to evaluate harmfulness and agency without neglecting the subjectivity of the people who undergo gendered genital modifications (GGMo).

Furthermore, there is a lack of ethnography that addresses the biomedical setting of male cosmetic surgery, genital piercing and IS. It is important to study how cultural assumptions regarding genitals, beauty, sexuality, ageing, the inviolability of the body and gender norms are embedded in scientific knowledge and clinical work surrounding genital surgery in different settings. Understanding the point of view of professionals and the ‘delegated biopolitics’ [124] is a new challenge; this concept of biopolitics encompasses three dimensions of delegation: delegation to the patients (who must consider options and consent to the consequences of their decisions); delegation to the healthcare professionals (who, during one-on-one consultations, are obliged to test the strength and steadiness of their patients’ desires and how informed they are); and delegation to the professionals in biology and medicine (who must implement their instruments of self-control in ethics committees and hospital protocols). The analysis of this triple delegation represents a possible key to understanding the different types of power that could be exercised over individuals, along with their needs or desires and the role of institutions in the choices of individuals.

In this context, the negotiation of consent and mobilisation of cultural meanings pertaining to health, beauty and sexual enhancement are presented as new challenges. The progressive medicalisation of FGM/C in certain contexts and the rise of other genital surgeries are issues that require attention. Furthermore, the literature that addresses intimate cosmetic surgery under neoliberalism does not adequately account for new gender surgery technologies.

By theoretically discussing consent, violence and harm, philosophical and bioethical literature [125], along with gender, political and legal studies [108], some scholars have tried to account for the multiple forms of genital surgery [126]. A problem with the existing literature, however, is the relative lack of attention to subjectivity and gendered multi-positionality, which are central in the anthropological debate. However, these notions become fundamental when rearticulating the relationship between universalism and cultural relativism.Footnote 7 The theoretical discussion of violence must consider the historicity and knowledge of the different cosmological and symbolic meanings concerning each practice in its local (and trans-local) context.

The anthropologist Veena Das argued that the concept of violence is extremely unstable. She proposed that, instead of policing the definition of violence, we accept its instability as crucial to the understanding of how the reality of violence includes its virtuality and has the potential to make and undo social worlds [128]. Also, the sex/gender system is crucial for understanding what connects local and global visions and their historicity.

Furthermore, the literature has not addressed gender binarism as the intersecting and distinguishing feature of these practices. The emerging movements (e.g., intactivism)Footnote 8 [129] reveal the idea of the ‘inviolability’ of one’s genitals and the dynamics of re-naturalisation of the body; consequently, a denunciation of male modification as a form of gender violence appears. The contestation of ‘forced’ gender binarism (as in intersex surgeries) could foster unprecedented positions of pro-body integrity. Comparative and fieldwork research that interrogates this apparent paradox is increasingly necessary. As it stands, there is yet insufficient historical and ethnographic inquiries into the new anti-circumcision and intactivist movements or secularist, religious, and state-new prohibitionist policies against IS [130].

Conclusion

GGMo is an increasingly popular biomedical set of practices that entails compelling issues, such as public health, well-being and potential harm; sexuality, virtue, and moral and social norms; gender empowerment and, conversely, gender violence; and prohibitive and permissive policies and laws. GGMo can be delivered through various methods, following different biomedical settings and different cosmologies. However, all forms of genital surgery entail issues surrounding gender enhancements and agency. Today, GGMo encompasses male circumcision, FGM/C, clitoral reconstruction after FGM/C, GRS, IS on newborns and CGS. Until now, the production of knowledge and public discourse has kept FGM/C separate from other forms of genital surgery. Furthermore, discussions of FGM/C have been built on a performative order of discourse, which is now incorporated by social actors and public opinion. Because it is considered a form of violence against women and girls, FGM/C’s social and cultural dimensions should receive increased scientific attention.

In contrast, CGS, which can also involve children, has thus far remained unexplored, particularly concerning its potential harmfulness. We need to ask how these practices are selectively condemned and commended by the different actors in the field and which social and moral stakes are encompassed. Moreover, the theoretical stance that considers female GCS as the unracialized mirror of FGM/C has developed without any ethnographic description of how aesthetic genital surgery is morally legitimated, culturally sought, socially organised and delivered.

The selective production of knowledge has reinforced the social and political polarisation between practices labelled as customary and barbaric and others considered to be modern, free and empowering. Important matters of racism, neo-colonialism, ethnocentrism and victimisation have arisen from this divide. Moreover, the laws and public policies criminalising FGM/C have resulted in the clandestine delivery of these practices.

Until now, mutilation was the name given to a specific form of genital surgery cast as non-therapeutic and targeting only women and girls. Recently, the characteristic of harmfulness has been increasingly attributed to those practices that pertain to biomedicine, which include IS, GRS and male circumcision. New social movements have emerged (e.g., intactivists, post- and de-colonial feminists), and they raise relevant questions about consent, the role of the state and biomedicine in preventing harm, and the moral threshold regarding the modifiability or inviolability of the gendered body. Understanding this change entails considering questions too often left to specialists in medicine and psychiatry (e.g., the question of what is therapeutic or harmful in genital surgery). An anthropological and ethnographic approach that can account for the socio-cultural meanings of health, sexuality, purity and beauty is fundamental. Nevertheless, we need an integrated and collaborative anthropological analysis of how, in this realm, consent, integrity and autonomy articulate with the concepts of agency and subjectivity in the sex/gender system.

Change history

13 February 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00668-7

Notes

As defined by Michel Foucault, the discourse relates to ways of organising knowledge and meaning in a social system historically, via modes of subjectivity and power relations. The exertion of power shapes concepts and categories for legitimating knowledge into a discursive order; the discourse fixes meanings in a way that is favourable to the dominant political system and the logic that underlies its production. In this sense, the discourse normalises and homogenises, including through interventions into the bodies and subjectivities of those it dominates (incorporation). Because it can come to be interpreted as objective, stable and universal, this process constructs a system of control (biopower) and involves various kinds of bodily discipline (e.g., in genital modifications and in the sex/gender system).

The anthropologist Gayle Rubin defines the sex/gender system as ‘the set of arrangements by which a society transforms biological sexuality into products of human activity, and in which these transformed sexual needs are satisfied’ (1975). Because sexuality is unrelated to anatomical genitalia, biology is not a problem; rather, structures of social organisation (such as inequalities of status and power) are problematic. Kinship systems and child education are, among other things, observable and empirical forms of local sex/gender systems. The oppression and subordination of women can be interpreted as a product of the relationships (heterosexual) by which sex and gender are hierarchically organised and produced. Sex/gender system is a fundamental concept to understand how sexuality is categorised and how gender is produced socially. It is also a tool to deconstruct the trend toward biological determinism and for analysing different forms of the family and their transformations over time and space.

Subjectivity refers to a specific cultural and historical consciousness at both the individual and collective level. At the individual level, actors are always at least partially ‘knowing subjects’ in that they have some degree of reflexivity about themselves and their desires. At the collective level is the collective sensibility of socially interrelated actors. Consciousness, in this sense, is always part of people’s subjectivities and part of the public culture.

Since 1999, when I started fieldwork in Italy and Rwanda, I substituted the term ‘mutilation’ with ‘modification’ to build a neutral, prejudice-free space with social actors. Using the word ‘modification’ permitted me to refuse any generalisation and simplification of talking with women at an egalitarian level. This methodological cultural relativism, which was not a form of justification, taught me that reversible or permanent body modifications are universal in the sex/gender system.

See, e.g. the Dafay Network, ‘a network of actors in the field of research, artivism, & political and activist action, engaged in the decolonization of knowledges, discourses and intervention practices on Female genital cutting in Europe and the global North’ https://baadon.com/en/workshops/. See also Fuambai S. Ahmadu’s website, http://www.fuambaisiaahmadu.com. Fuambai S. Ahmadu is both a professional anthropologist and an initiated member of the Bondo society of Sierra Leone. She says she was circumcised, not mutilated, and she chose to undergo the procedure. [87].

The International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery provides the only statistics about the number and type of aesthetic procedures performed on a global scale. https://www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/ISAPS-Global-Survey-Results-2018-new.pdf

Marie Benedicte Dembour, anthropologist of law, has proposed the ‘theory of the pendulum’. She argues that universalism and relativism are usually presented as two opposite and incompatible moral (or epistemological) positions regarding human rights. The position proposed by the author is unstable and encompasses both the universalist and the relativist stances. It is not a middle position but an in-between position that makes sense of the fact that a social actor should be drawn into a pendulum motion. [127].

For example, the French association Droit au corps that aims ‘to promote the abandonment of all forms of sexual mutilation - female, male, transgender and intersex: excision, circumcision or other - i.e. any modification of a sexual organ practised on an individual without his or her free and informed consent, and without medical necessity.’ (https://www.droitaucorps.com). Recently also some newspapers covered this item, see The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/jul/21/foreskin-reclaimers-the-intactivists-fighting-infant-male-circumcision.

References

Talbot PA. Clitoridectomy in West Africa. Man. 1925;25:184–85.

de Villeneuve A. Étude sur une coutume Somalie: Les femmes cousues. Jafr. 1937;7:15–32. https://doi.org/10.3406/jafr.1937.1619

Yunis Y. Notes on the Baggara and Nuna of western Kordofan. Sudan Notes Rec. 1922;5:200–7.

Worsley A. Infibulation and female circumcision: a study of a little-known custom. BJOG: Int J OG. 1938;45:686–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.1938.tb11160.x

Gudgeon WE. Phallic emblem from Atiu Island. J Polynesian Soc. 1904;13:210–2.

Elkin AP. Anthropology and the future of the Australian Aborigines. Oceania. 1934;5:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4461.1934.tb00128.x

Wheelwright CA. Native circumcision lodges in the Zoutpansberg District. J Anthropological Inst Gt Br Irel. 1905;35:251–5. https://doi.org/10.2307/2843065

Basedow H. Subincision and kindred rites of the Australian Aboriginal. J R Anthropological Inst Gt Br Irel. 1927;57:123–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2843680

Ashley-Montagu MF. The origin of subincision in Australia. Oceania. 1937;8:193–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1834-4461.1937.tb00415.x

Ackerknecht EH. Primitive surgery. Am Anthropologist. 1947;49:25–45. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1947.49.1.02a00030

Crawley AE. Sexual taboo: A study in the relations of the sexes (part III). J Anthropological Inst Gt Br Irel. 1895;24:430. https://doi.org/10.2307/2842190

Bryk F. Circumcision in man and woman: Its history, psychology and ethnology. NewYork: American Ethnological Press; 1934.

Puccioni N. Delle deformazioni e mutilazioni artificiali etniche più in uso. Archivio per l’Antropologia e l’Etnologia. 1904;34:391–401.

Leakey LS. The Kikuyu problem of the initiation of girls. J R Anthropological Inst Gt Br Irel. 1931;61:277–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/2843834

Van Gennep A, Vizedom MB, Caffee GL, Kimball ST. The rites of passage. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1960.

Turner V. Three symbols of passage in Ndembu circumcision ritual. In: Gluckman M (ed.) Essays on the ritual of social relations. Ithaca, NY, Manchester University Press; 1962. p.124-73.

Dieterlen G. Essai sur la religion bambara. Bruxelles, Editions de l’Université de Bruxelles; 1951.

Mauss M. Techniques of the body. Econ Soc. 1973;2:70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003

Bloch M. From blessing to violence: History and ideology in the circumcision ritual of the Merina of Madagascar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.1986.

Smith C. Who defines «mutilation»? Challenging imperialism in the discourse of female genital cutting. Feminist Formations. 2011;23:25–46.

Werunga J, Reimer-Kirkham S, Ewashen C. A decolonizing methodology for health research on female genital cutting. Adv Nurs Sci. 2016;39:150–64.

Gele AA, Kumar B, Hjelde KH, Sundby J. Attitudes toward female circumcision among Somali immigrants in Oslo: A qualitative study. Int J Women’s Health. 2012;4:7–17. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S27577

O’Neill S. Purity, cleanliness, and smell: Female circumcision, embodiment, and discourses among midwives and excisers in Fouta Toro, Senegal. J R Anthropol Inst. 2018;24:730–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12914

Gruenbaum E. Socio‐cultural dynamics of female genital cutting: Research findings, gaps, and directions. Cult, Health Sexuality. 2005;7:429–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050500262953

Boddy J. Womb as oasis: The symbolic context of pharaonic circumcision in rural northern Sudan. Am Ethnologist. 1982;9:682–98. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1982.9.4.02a00040

Johansen RE. Undoing female genital cutting: Perceptions and experiences of infibulation, defibulation and virginity among Somali and Sudanese migrants in Norway. Cult, Health Sexuality. 2017;19:528–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2016.1239838

Obermeyer CM. The health consequences of female circumcision: Science, advocacy, and standards of evidence. Med Anthropol Q. 2003;17:394–412. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-26

Bourdieu P. Les rites comme actes d’institution. Actes de la Rech en Sci Soc. 1982;43:58–63. https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1982.2159

Fusaschi M. I segni sul corpo: Per un’antropologia delle modificazioni dei genitali femminili. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri; 2003.

Tamale S. Eroticism, sensuality and “women’s secrets” among the Baganda: A critical analysis. Feminist Africa. 2006;5:9–36.

Gluckman M. The role of the sexes in Wiko circumcision ceremonies. In: Fortes M (ed.) Social structure: Studies presented to A.R. Radcliffe-Brown. Oxford: Clarendon; 1949. p. 145–67.

Fusaschi M. A paradoxical Rwandan female genital “mutilation”. In Fusaschi M, Cavatorta G, editors. FGM/C: From medicine to critical anthropology. Rome: Meti; 2018, p. 107-23.

World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/female-genital-mutilation

Silverman EK. Anthropology and Circumcision. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2004;33:419–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.143706

Droz Y. Circoncision Féminine et Masculine En Pays Kikuyu: Rite d’institution. Division Sociale et Droits de l’Homme. Cah d’Études Africaines. 2000;40:215–40. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.172

Rubin G. The traffic in women: Notes on the ‘political economy’ of sex. In Reiter, RR, editor. Toward an anthropology of women. New York and London: Monthly Review Press; 1975. p. 157–210.

Merli C. Male and female genital cutting among Southern Thailand’s Muslims: rituals, biomedical practice, and local discourses. Cult, Health Sexuality. 2010;12:725–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691051003683109

Balandier G. The Sociology of Black Africa: Social Dynamics in Central Africa. London. André Deutsch; 1970.

Boddy JP. Civilizing women: British crusades in colonial Sudan. Princeton. Princeton University Press; 2007

Shell-Duncan B, Hernlund Y (eds.) Female “circumcision” in Africa: Culture, controversy, and change. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2000

Ahmadu Fuambai S, Shweder Richard A. Disputing the myth of the sexual dysfunction of circumcised women: An interview with Fuambai S. Ahmadu by Richard A. Shweder”. Anthropol Today. 2009;25:14–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8322.2009.00699.x S2CID 17286057

Gruenbaum E. The female circumcision controversy: An anthropological perspective. Philadelphia University of Pennsylvania Press; 2001.

Johnsdotter S. Projected cultural histories of the cutting of female genitalia: A poor reflection as in a mirror. Hist Anthropol. 2012;23:91–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/02757206.2012.649270

Earp BD, Johnsdotter S. Current critiques of the WHO policy on female genital mutilation. Int J Impot Res. 2021;33:196–209. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-020-0302-0

Johnsdotter S, Johansen ER. Introduction. Female genital cutting: the global north and south. Holmbergs, Malmö; 2020. p. 7-22.

Shell-Duncan B. From health to human rights: Female genital cutting and the politics of intervention. Am Anthropologist. 2008;110:225–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2008.00028.x

Fusaschi M. Humanitarian bodies: Gender, moral economy and genital modification in Italian immigration policy. Cah d’Études Africaines. 2015;217:11–28. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesafricaines.17985

Ahmadu FS. Rites and wrongs: An insider/outsider reflects on power and excision. In: Shell-Duncan B, Hernlund Y (eds.) Female “circumcision” in Africa: Culture, controversy, and change. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2000. p. 283-315.

Hernlund Y, Shell-Duncan B (eds.) Transcultural bodies: Female genital cutting in global context. New Brunswick, N.J Rutgers University Press; 2007.

Logie CH, Perez-Brumer A, Parker R. The contested global politics of pleasure and danger: Sexuality, gender, health and human rights. Glob Public Health. 2021;16:651–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1893373

Kessler SJ. The medical construction of gender: Case management of intersexed infants. Signs. 1990;16:3–26. https://doi.org/10.1086/494643

Monro S, Carpenter M, Crocetti D, Davis G, Garland F, Griffiths D, et al. Intersex: Cultural and social perspectives. Cult, Health Sexuality. 2021;23:431–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.1899529

Jones M. Intersex genital mutilation – A Western version of FGM. Int J Children’s Rights. 2017;25:396–411. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02502008

WHO, Preventing HIV through safe voluntary medical male circumcision for adolescent boys and men in generalized HIV epidemics: recommendations and key considerations. Policy Brief. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/978-92-4-000966-0

Monro S, Crocetti D, Yeadon-Lee T. Intersex/variations of sex characteristics and DSD citizenship in the UK, Italy and Switzerland. Citizsh Stud. 2019;23:780–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2019.1645813

Earp BD, Darby R. Circumcision, autonomy and public health. Public Health Ethics. 2019;12:64–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/phe/phx024

Berliner D, Lambek M, Shweder R, Irvine R, Piette A. Anthropology and the study of contradictions. HAU J Ethnographic Theory. 2016;6:1–27. https://doi.org/10.14318/hau6.1.002

The Brussels Collaboration on Bodily Integrity. Medically unnecessary genital cutting and the rights of the child: Moving toward consensus. Am J Bioeth. 2019;19:17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2019.1643945

Fusaschi M, Cavatorta G (eds.) FGM/C: From medicine to critical anthropology. Turin: Meti Edizioni; 2018.

Fausto-Sterling, A Sexing the body: Gender politics and the construction of sexuality. New York: Basic Books; 2000.

Fusaschi M. Making the invisible ethnography visible: The peculiar relationship between Italian anthropology and feminism. In: Matera V, Biscaldi A (eds.) Ethnography. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. 2021. p.371-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51720-5_16

Butler J. Thinking with Saba Mahmood. Critical. 2019;2:5–9. https://doi.org/10.1215/26410478-7769710

Thomas L “‘Ngaitana (I will circumcise myself)’: Lessons from Colonial Campaigns to Ban Excision in Meru, Kenya”. In: Shell-Duncan B, Hernlund, Y (eds.) Female “Circumcision” in Africa. Lynne. 2000. p. 129-50.

Natsoulas T. The politicization of the ban on female circumcision and the rise of the Independent School Movement in Kenya. Afr Asian Stud 1998;33:137–58. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852182×X00011

Toubia N, Izett S. Female genital mutilation: an overview. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. 73 pag.

Merry SE. Human rights law and the demonization of culture (and anthropology along the way). Political Leg Anthropol Rev. 2003;26:55–76. https://doi.org/10.1525/pol.2003.26.1.55

Cavatorta G, Fusaschi M. Le modificazioni dei genitali femminili nel discorso dei diritti umani delle donne. Morale umanitaria, assoggettamento e vernacolarizzazione. Scienza & Politica. 2021;33:33–51. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1825-9618/13779

UNICEF, Innocenti Research Centre. Innocenti digest. [No. 12]. Florence, Italy: UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre; 2005.

World Health Organization & Candau, Marcolino Gomes. (1960) . The work of WHO, 1959: annual report of the Director-General to the World Health Assembly and to the United Nations. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/85722

Narayan U. Essence of culture and a sense of history: a feminist critique of cultural essentialism. Hypatia. 1998;13:87 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01227.x

Kapur R. The tragedy of victimization rhetoric: Resurrecting the native subject in international/postcolonial feminist legal politics. Harv Hum Rights Law J. 2002;15:1 https://ssrn.com/abstract=779824

Fusaschi M Quando il corpo è delle Altre. Retoriche della pietà e umanitarismo spettacolo. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri; 2011.

Longman C, Bradley T, editors. Interrogating harmful cultural practices: Gender, culture and coercion. Farnham, Surrey, England; Burlington, VT, Ashgate; 2015.

Murdock GP. World ethnographic sample. Am Anthropologist. 1967;59:664–87. https://doi.org/10.1525/aa.1957.59.4.02a00090

Hayes RO. Female genital mutilation, fertility control, women’s roles, and the patrilineage in modern Sudan: A functional analysis. Am Ethnologist. 1975;2:617–33. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1975.2.4.02a00030

Moore HL. A passion for difference: Essays in anthropology and gender. Polity; 1994.

Ortner SB. Anthropology and social theory: Culture, power, and the acting subject. Duke University Press; 2006.

Biehl JG, Good B, Kleinman A, editors. Subjectivity: Ethnographic investigations. University of California Press; 2007.

Johnsdotter S, Johansen EB. Introduction. In: Johnsdotter S, editor. Female genital cutting: The global north and south. Holmbergs, Malmö. Malmö universitet; 2020. p. 8-10.

Gosselin C. Feminism, anthropology and the politics of excision in Mali: Global and local debates in a postcolonial world. Anthropologica. 2000;42:43–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/25605957

Mohanty CT. Under Western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. Feminist Review. 1988:61.

Hosken F. Genital mutilation of women in Africa. Munger Afr Libr Notes. 1976;36:3–21.

Adjamagbo A, Calvès A-E. L’émancipation féminine sous contrainte. Autrepart. 2012;61:3–21. https://doi.org/10.3917/autr.061.0003

Fassin D. Humanitarian reason. A moral history of the present. University of California Press; 2011.

Gruenbaum E. Tensions and movements: Female genital cutting in the global North and South, then and now. In: Johnsdotter S, editor. Female genital cutting: the global North and South. Holmbergs, Malmö. Malmö universitet; 2020. p. 23-58.

Baer M. and Brysk A. New rights for private wrongs: Female genital mutilation and global framing dialogues. In: Clifford B, editor. The international struggle for new human rights, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2009, p. 93-107.

Walley CJ. Searching for “voices”: Feminism, anthropology, and the global debate over female genital operations. Cultural Anthropol. 1997;12:405–38.

Obermeyer CM. Female genital surgeries: The known, the unknown, and the unknowable. Med Anthropol Q. 1999;13:79–106.

Elamin W, Mason-Jones AJ. Female genital mutilation/cutting: A systematic review and meta-ethnography exploring women’s views of why it exists and persists. Int J Sex health. 2020;32:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2019.1683115

Merry SE. Human rights and gender violence: Translating international law into local justice. University of Chicago Press; 2006.

Hodžić S. The twilight of cutting: African activism and life after NGOs. Oakland University of California Press; 2017.

Abosede AG. Making modern girls: A history of girlhood, labor, and social development in colonial Lagos. Ohio University Press. 2014.

Fusaschi M. Trouble dans le gukuna rwandais: Fémocratie, féminismes et anthropologie critique. Anuac. 2020;9:17–43. https://doi.org/10.7340/ANUAC2239-625X-4102

Merry SE. The seductions of quantification: measuring human rights, gender violence, and sex trafficking. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press; 2016. p. 249.

Fassin D. Les économies morales revisitées. Annales Hist, Sci Soc. 2009;64:1257.

Kaw E. Medicalization of Racial Features: Asian American Women and Cosmetic Surgery. Med Anthropol Q. 1993;7:74–89.

Morgan KP. Women and the knife: Cosmetic surgery and the colonization of women’s bodies. Hypatia. 1991;6:25–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1527-2001.1991.tb00254.x

UNICEF. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/female-genital-mutilation/

Butler J. The psychic life of power theories in subjection. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press; 1997.

Ahmadi A. Recreating virginity in Iran: Hymenoplasty as a form of resistance. Med Anthropol Q. 2016;30:222–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/maq.12202

Wynn LL. ‘Like a virgin’: Hymenoplasty and secret marriage in Egypt. Med Anthropol. 2016;35:547–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2016.1143822

Campbell J, Gillis J. A review of penile elongation surgery. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6:69–78. https://doi.org/10.21037/tau.2016.11.19

Creighton SM, Liao LM, editors. Female genital cosmetic surgery: Solution to what problem? Cambridge, United Kingdom; New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2018.

Abdulcadir J. Psychosexual health after female genital mutilation/cutting and clitoral reconstruction: What does the evidence say? In: Griffin G, Jordal M, editors. Body, migration, re/constructive surgeries: Making the gendered body in a globalized world. Routledge; 2019. p. 19-38.

Munzer SR. Examining nontherapeutic circumcision. Health Matrix. 2018;28:1–77.

Earp BD. Sex and circumcision. Am J Bioeth. 2015;15:43–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2014.991000

De Lauretis T. Technologies of gender: Essays on theory, film, and fiction. Theories of Representation and Difference. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1987.

Ehrenreich N. Barr M. Intersex surgery, female genital cutting, and the selective condemnation of cultural practices. Harv Civ Rts-Civ Lib L Rev. 2005;40:71–140.

DeLaet DL. Framing male circumcision as a human rights issue? Contributions to the debate over the universality of human rights. J Hum Rts. 2009;8:405–26.

Villani M. Reconstructing sexuality after excision: The medical tools. Medical Anthropology. 2020;39:269-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2019.1665670

European Institute for Gender Equality. Literature and legislation. Available from: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/literature-and-legislation?vt[]=122

Mowat H, McDonald K, Dobson AS, Fisher J, Kirkman M. The contribution of online content to the promotion and normalisation of female genital cosmetic surgery: A systematic review of the literature. BMC Women’s Health. 2015;15:110 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-015-0271-5

Liao LM, Hegarty P, Creighton SM, Lundberg T, Roen K. Clitoral surgery on minors: an interview study with clinical experts of differences of sex development. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e025821. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025821

Fusaschi M. Designer vagina: Immaginari dell’indecenza o ritorno all’età dell’innocenza? Genes: Riv Della Socà Ital delle Storiche. 2011;X:63–84. https://doi.org/10.1400/180149

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Vaginal “rejuvenation” and cosmetic vaginal procedures, ACOG Committee Opinion No. 376. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:737–38.

Braun V, Kitzinger C. The perfectible vagina: Size matters. Cult, Health Sexuality. 2001;3:263–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050152484704

Earp BD. Female genital mutilation (FGM) and male circumcision: Should there be a separate ethical discourse? Practical Ethics. University of Oxford; 2014. Available from: https://philpapers.org/archive/EARFGM.pdf

Coene G. Male circumcision: the emergence of a harmful cultural practice in the West? In: Fusaschi M, Cavatorta G, editors. FGM/C: From medicine to critical anthropology. Rome: Meti; 2018, p. 140.

Dowsett GW, Couch M. Male circumcision and HIV prevention: Is there really enough of the right kind of evidence? Reprod Health Matters. 2007;15:33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29302-4

Auchter J. Forced male circumcision: Gender-based violence in Kenya. Int Aff. 2017;93:1339–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iix183

Svoboda JS, Van Howe RS, Dwyer JG. Informed consent for neonatal circumcision: An ethical and legal conundrum. J Contemp Health Law Policy. 2000;17:61–133.

Denniston GC, Hodges FM, Milos MF, editors. Genital autonomy: Protecting personal choice. Dordrecht, New York: Springer; 2010.

Scheper-Hughes N, Lock MM. The mindful body: A prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Med Anthropol Q. 1987;1:6–41. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1987.1.1.02a00020

Memmi D. Civilizing “life itself”: Elias and Foucault. In: Landini TS, Dépelteau F, editors. Norbert Elias and Empirical Research. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US; 2014. pag. 111-23.

Earp BD. Male or female genital cutting: why ‘health benefits’ are morally irrelevant. J Med Ethics. 2021;47:92–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2020-106782

Svoboda. Promoting genital autonomy by exploring commonalities between male, female, intersex, and cosmetic female genital cutting. Glob Discourse. 2013;3:237–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2013.804757

Dembour M. Following the movement of a pendulum: between universalism and relativism. In: Cowan JK, Dembour M, Wilson RA, editor. Culture and rights. 10 ed. Cambridge University Press; 2001. pag. 56-79

Das V. Violence, gender, and subjectivity. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2008;37:283–99. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.36.081406.094430

Johnsdotter S. Girls and Boys as Victims: Asymmetries and dynamics in European public discourses on genital modifications in children In Fusaschi M, Cavatorta G, editors. FGM/C: From medicine to critical anthropology. Rome: Meti; 2018, pag. 31-47.

Florquin S, Richard F. Critical discussion on female genital cutting/mutilation and other genital alterations: Perspectives from a women’s rights NGO. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2020;12:292–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-020-00277-1

Oyěwùmí O. The invention of women. Making an African sense of Western gender discourses. NED-New edition. University of Minnesota Press; 1997.

Tamale S. (ed.) African sexualities: A reader. Cape Town, Dakar, Nairobi and Oxford. Pambazuka Press; 2011.

Massad J. Desiring Arabs. University of Chicago Press; 2007.

Tamale S (ed.) African sexualities: A reader. Cape Town, Dakar, Nairobi and Oxford. Pambazuka Press; 2011, p. 2.

UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCHR, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO. Eliminating female genital mutilation: an interagency statement. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43839/9789241596442_eng.pdf?sequence=1

European Institute for Gender Equality. Available from: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/resources/italy/valutazione-quantitativa-e-qualitativa-del-fenomeno-delle-mutilazioni-genitali-femminili-italia

Fusaschi M. Modifications génitales féminines en Europe: raison humanitaire et universalismes ethnocentriques. Synergies Ital. 2014;10:95–107.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the reviewers and the associate editor for insightful suggestions that considerably improved the final version of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised due to retrospective Open Access order.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fusaschi, M. Gendered genital modifications in critical anthropology: from discourses on FGM/C to new technologies in the sex/gender system. Int J Impot Res 35, 6–15 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00542-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00542-y

This article is cited by

-

Rethinking the Definition of Medicalized Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting

Archives of Sexual Behavior (2024)

-

Child genital cutting and surgery across cultures, sex, and gender. Part 1: female, male, intersex—and trans? The difficulty of drawing distinctions

International Journal of Impotence Research (2023)

-

Child genital cutting and surgery across cultures, sex, and gender. Part 2: assessing consent and medical necessity in “endosex” modifications

International Journal of Impotence Research (2023)

-

The ethics of child genital cutting. When does a violation occur? Comments on “Defending an inclusive right to genital and bodily integrity for children” by Dr. Kate Goldie Townsend

International Journal of Impotence Research (2023)

-

Health outcomes and female genital mutilation/cutting: how much is due to the cutting itself?

International Journal of Impotence Research (2023)