Abstract

The 2017 US guidelines for pediatric hypertension place considerable emphasis on blood pressure measurements, which are the cornerstone for hypertension diagnosis and management. It is recognized that when the diagnosis of hypertension is based solely on office blood pressure measurements, many children are misclassified (over- or underdiagnosed). Therefore, out-of-office blood pressure evaluations using ambulatory or home blood pressure monitoring are often necessary to obtain an accurate diagnosis. Strong evidence for the diagnostic and clinical value of ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children has justified its central role in decision making in recent pediatric recommendations. However, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is not widely accessible in primary care. There is little evidence for home blood pressure monitoring in children, yet this method is widely available and feasible for the evaluation of elevated blood pressure in children. This article presents a case for using home blood pressure monitoring for the management of children with suspected or treated hypertension in clinical practice in comparison to using office measurements or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, as well as its optimal application. More research on home blood pressure monitoring in children is urgently needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hypertension in children and adolescents is an emerging public health issue that is mainly attributed to the rising rate of pediatric obesity [1,2,3]. Thirteen years after the ‘Fourth Report on the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents’ was published in the US in 2004 [1], the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) published new guidelines for pediatric hypertension [2, 3]. The attention that the 2017 AAP guidelines place on blood pressure (BP) measurements and the diagnosis of hypertension is impressive. The part devoted to ‘BP Measurement’ made up one-third of the text’s pages and one-fourth of its references. Seven of 8 changes presented as ‘significant’ address BP measurements and hypertension diagnosis, as well as 10 of the 30 ‘key action statements’ and 12 of the 27 ‘additional consensus opinion recommendations’ [2].

The strong commitment of the AAP to obtain more accurate BP measurements in clinical practice is expected to improve pediatric care because, as in adults, BP measurements are the sole test for hypertension diagnosis and management in children. Inadequate BP evaluation often leads to over-diagnosis, with consequent unnecessary investigations and long-term treatment, or underdiagnosis, with consequent undertreatment and exposure to future disease risk.

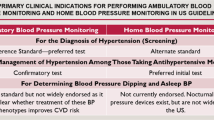

Methods available for BP evaluations in clinical practice are office BP measurements, ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) and home BP monitoring (HBPM) [2]. This article aims to (1) compare HBPM with office BP measurements and ABPM in children with suspected or treated hypertension, (2) discuss the 2017 AAP recommendations on BP measurements in children, and (3) present the optimal clinical application of HBPM in children on the basis of the current evidence.

The case for out-of-office BP measurements

Although office BP measurements remain the basis for hypertension evaluations in adults and children, it is recognized that out-of-office BP evaluations using ABPM or HBPM are often necessary to obtain an accurate diagnosis, mainly due to the white-coat hypertension (WCH) and masked hypertension (MH) phenomena, which are common among both untreated and treated individuals [2, 4]. Studies in general population samples of children and adolescents using either ABPM or HBPM showed that when office BP measurements are used for screening, one of two children with elevated office BP will have WCH, while many children with MH will be missed (Fig. 1) [5, 6]. Moreover, even with carefully taken office BP measurements in a hypertension clinic, WCH is as common as sustained hypertension, and again, children with MH are often missed (Fig. 1) [7]. Thus, office BP measurements should only be regarded as a screening method, the accuracy of which is improved with repeated visits [8]. Simple approaches to this should be developed [9]. However, when a diagnosis of hypertension is based solely on office BP measurements, more children are misclassified than correctly diagnosed.

Auscultatory versus automated (oscillometric) BP measurements

The 2017 AAP guidelines for pediatric hypertension recommend that the diagnosis of office hypertension be based on auscultatory BP measurements [2]. BP measurements taken with an automated (oscillometric) device can be used for screening, but elevated BP measurements need to be confirmed through auscultatory measurements [2]. Interestingly, ABPM is recommended as the ultimate diagnostic method for hypertension before starting treatment; however, this is performed almost exclusively using automated oscillometric devices [2]. Regarding HBPM, the AAP guidelines state that because of limited evidence, the method should not be used for diagnosis and that few oscillometric devices have been validated in children [2].

Indeed, published evidence on the accuracy of automated oscillometric BP monitors in children is limited. A recent systematic review identified 31 formal validation studies of oscillometric BP monitors in children, of which 42% were published a decade ago or longer [10]. Of these 31 studies, 16 evaluated devices for office BP measurements, 5 of which failed; 9 evaluated ABPM devices, of which 3 failed; and 6 evaluated HBPM devices, one of which failed [10]. The currently used normalcy tables for ABPM in children [11] are based on a single study that used an oscillometric ambulatory BP monitor (Spacelabs 90207) that exhibited questionable measurement accuracy for children in two validation studies (Table 1) [10, 12, 13]. In the first validation study, which studied 85 children and adolescents, the device failed the British Hypertension Society’s protocol criteria for systolic and diastolic BP and the US Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation’s protocol criteria for diastolic BP [12]. In the second validation study of 112 children and adolescents, the device passed the British Hypertension Society’s protocol criteria for both systolic and diastolic BP, but failed the US Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation’s protocol criteria for diastolic BP (Table 1) [13].

Thus, the accuracy of automated oscillometric BP measuring devices in children is imperfect, and accuracy is not any better for ABPM than it is for HBPM or office BP measurements [10]. Despite these deficiencies, the evidence supporting the superiority of ABPM over office BP measurements in children is indisputable, as indicated by comparative data on its association with preclinical target organ damage [14]. The advantage of using ABPM in children is well recognized; this advantage is mainly due to ABPM’s potential to improve the detection of children at increased cardiovascular risk, but unfortunately, to date, ABPM has not been widely adopted, and robust normative values are lacking [15].

Home versus ambulatory BP monitoring

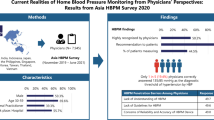

When considering office BP measurements, ABPM and HBPM in children (Table 2), an important factor that should be considered is that office BP measurements are widely available and are used for screening and HBPM is widely available in the general population, yet ABPM is unfortunately limited to hypertension specialists—mainly in pediatric nephrology centers [15, 16]. Thus, the use of HBPM in children should be standardized in clinical practice and should be further supported by future studies, and the use of ABPM should be expanded in additional settings.

Barriers to performing ABPM that are faced by primary care providers have been recognized. In a recent survey in the US, the top-ranked barriers in adults were (1) challenges in accessing ABPM, (2) costs of ABPM, (3) concerns about the willingness or abilities of patients to successfully perform ABPM, and (4) concerns about its accuracy and benefits [17]. Indeed, the cost of the devices is high, ABPM is inadequately reimbursed in many countries, fitting the device and downloading the data take time, and occasionally, users are unwilling to wear the device, particularly for repeated evaluations.

For HBPM, surveys in the US, Canada and Germany showed that > 70% of pediatric nephrologists routinely apply this method in children with hypertension or renal disease, and 64% of them consider HBPM as more important than office BP measurements [18, 19]. Furthermore, studies in adults have shown that more patients prefer to use HBPM than ABPM [4], yet such data in children are still lacking. However, there are barriers for utilizing HBPM in primary care as well. In the previously mentioned survey from the US [17], the top barriers to performing HBPM were (1) compliance with the correct protocol, (2) accuracy of the results, (3) out-of-pocket costs of the devices, and (4) time needed to instruct patients.

ABPM is promoted for the detection of WCH, MH and nocturnal hypertension [2]. For WCH detection, it is unfortunately very unlikely that many children with elevated office BP will be evaluated with ABPM in every-day clinical practice, outside of pediatric nephrology settings. Regarding HBPM, two studies comparing against ABPM (taken as the reference) for WCH diagnosis in children showed high sensitivity and specificity (74-89% and 91-92%, respectively) [7, 20], which are in line with studies in adults [4]. Thus, HBPM appears to be a reliable screening tool for WCH and is also a useful and realistic alternative when ABPM is not available. Although the 2017 US guidelines for adults state that either ABPM or HBPM should be used to detect WCH [21], the 2017 AAP guidelines recommend that only ABPM should be used in children due to the limited evidence regarding the use of HBPM in children [2]. For MH, the AAP guidelines repeatedly emphasize the usefulness of ABPM [2], yet most of such children are unlikely to be subjected to ABPM due to their low office BPs. Since the AAP guidelines include ‘obesity’ in the list of high-risk conditions for which ABPM may be useful, the candidate population is large. In adults, HBPM is regarded as a reliable alternative to ABPM for detecting MH; [4] however, in children two studies have revealed high specificity (92-96%) but low sensitivity (36–38%) [7, 20], and further research is needed. For nocturnal hypertension, ABPM is indeed a unique tool, yet novel HBPM devices can also assess BP during sleep, though to date, they have not been studied in children [22].

Thus, it is clear that, in children, the research evidence on ABPM is stronger than for HBPM. However, the preliminary evidence in children is in line with that in adults, showing that the reproducibility of HBPM is superior to that of office BP measurements and close to that of ABPM [23, 24]. Moreover, the association of HBPM with several indices of preclinical target-organ damage appears to be similar to ABPM and superior to office BP measurements [25, 26].

Efforts should be made to increase the amount of research performed regarding the utility and effectiveness of HBPM in children in primary care settings, as this modality may be easier and more preferable for families, particularly for repeated use in children with treated hypertension. HBPM is a useful and feasible method for assessing out-of-office BP in most untreated or treated children with possible WCH or MH. ABPM for confirming these diagnoses is preferable for children, yet in practice, a repeat HBPM session under medical supervision will probably be the most realistic option for most children. For the long-term follow-up of cases with treated hypertension, HBPM appears to be more suitable, acceptable, and cost-effective than ABPM [4]. Thus, HBPM has been endorsed by the 2017 US guidelines for hypertension for adults, in which HBPM plays a primary role in detecting WCH or masked uncontrolled hypertension in patients on drug therapy [21].

Application of home BP monitoring in clinical practice

Several issues with using HBPM in children require further investigation. However, in the last decade, evidence has been accumulating, and the findings are in line with those of studies conducted with adults [4, 27]. Although the evidence for using ABPM in children is stronger, at the present time and in the years to come, HBPM will remain more easily accessible in primary care than ABPM [16]. It is clear that more data regarding HBPM in children must be obtained. However, since ABPM is not widely available, the lack of available data should not prevent practicing physicians from applying HBPM in clinical practice [18, 19]. This is expected to refine the diagnosis of hypertension compared to the use of office BP measurements alone. Thus, methodological guidance regarding HBPM that is based on available data or derived from an extrapolation of evidence in adults appears to be a reasonable strategy at the present time, at least in settings where ABPM is not available.

For the optimal application of HBPM in children in clinical practice, recommendations need to be provided for the selection of devices, conditions of measurement, monitoring schedule, and interpretation of results (Table 3). An important difference in children and adolescents is that their daytime ambulatory BP measurements are significantly higher than their home BP measurements, whereas there is no such difference in adults. This difference has been demonstrated in a review of comparative studies [27] and in a comparison of the 95th percentiles of the normalcy tables for HBPM and daytime ABPM in children [28]. This can most likely be attributed to young individuals’ high levels of physical activity during the day, which is reflected in ABPM results. Practical recommendations for applying HBPM in children and adolescents in clinical practice are presented in Table 3 [4, 29, 30], and BP thresholds for home hypertension detection by gender and height are shown in Table 4 [28, 31]. As both ABPM and HBPM thresholds have been based on single and relatively small datasets, more data are needed.

Conclusions

The 2017 AAP guidelines for pediatric hypertension place considerable emphasis on BP measurements, which are essential for the accurate diagnosis of hypertension as well as treatment titration. It is recognized that many children are over- or underdiagnosed when only office BP measurements are used. Therefore, out-of-office BP evaluations using ABPM (as the preferred method) or HBPM are often necessary for accurate diagnoses. Although ABPM is better studied in children than HBPM, it is not easily accessible in primary care, and HBPM might be preferred by patients for repeated evaluations. HBPM is widely available in clinical practice and is used in the evaluation of children with elevated BP. Clear recommendations need to be provided to practicing doctors on the standardization and optimal application of HBPM in clinical practice based on the available evidence. Relevant research questions on the practical application of HBPM in children should be added to the pediatric hypertension research agenda and should be addressed in future studies.

References

National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children and Adolescents. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;114:555–76.

Flynn JT, Kaelber DC, Baker-Smith CM, Blowey D, Carroll AE, Daniels SR, et al. Subcommittee on screening and management of high blood pressure in children. Clinical practice guideline for screening and management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20171904.

Flynn JT, Falkner BE. New Clinical practice guideline for the management of high blood pressure in children and adolescents. Hypertension. 2017;70:683–6.

Parati G, Stergiou GS, Asmar R, Bilo G, de Leeuw P, Imai Y, et al. European Society of Hypertension guidelines for blood pressure monitoring at home: a summary report of the Second International consensus conference on home blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1505–26.

Lurbe E, Torro I, Alvarez V, Nawrot T, Paya R, Redon J, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and clinical significance of masked hypertension in youth. Hypertension. 2005;45:493–8.

Stergiou GS, Rarra VC, Yiannes NG. Prevalence and predictors of masked hypertension detected by home blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: the Arsakeion School study. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22:520–4.

Stergiou GS, Nasothimiou E, Giovas P, Kapoyiannis A, Vazeou A. Diagnosis of hypertension in children and adolescents based on home versus ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1556–62.

Sun J, Steffen LM, Ma C, Liang Y, Xi B. Definition of pediatric hypertension: are blood pressure measurements on three separate occasions necessary? Hypertens Res. 2017;40:496–503.

Ma C, Lu Q, Wang R, Liu X, Lou D, Yin F. A new modified blood pressure-to-height ratio simplifies the screening of hypertension in Han Chinese children. Hypertens Res. 2016;39:893–8.

Stergiou GS, Boubouchairopoulou N, Kollias A. Accuracy of automated blood pressure measurement in children: evidence, issues, and perspectives. Hypertension. 2017;69:1000–6.

Wühl E, Witte K, Soergel M, Mehls O, Schaefer F. German Working Group on Pediatric Hypertension. distribution of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure in children: normalized reference values and role of body dimensions. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1995–2007.

Belsha CW, Wells TG, Bowe Rice H, Neaville WA, Berry PL. Accuracy of the SpaceLabs 90207 ambulatory blood pressure monitor in children and adolescents. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:127–33.

Redwine KM, James LP, O’Riordan M, Sullivan JE, Blumer JL. Network of pediatric pharmacology research units. accuracy of the Spacelabs 90217 ambulatory blood pressure monitor in a pediatric population. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20:295–8.

Kollias A, Dafni M, Poulidakis E, Ntineri A, Stergiou GS, Out-of-office blood pressure and target organ damage in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2014;32:2315–31.

Flynn JT. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children: imperfect yet essential. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:2089–94.

Ostchega Y, Zhang G, Kit BK, Nwankwo T. Factors associated with home blood pressure monitoring among US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-4. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:1126–32.

Kronish IM, Kent S, Moise N, Shimbo D, Safford MM, Kynerd RE, et al. Barriers to conducting ambulatory and home blood pressure monitoring during hypertension screening in the United States. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2017;11:573–80.

Bald M, Hoyer PF. Measurement of blood pressure at home: survey among pediatric nephrologists. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:1058–62.

Woroniecki RP, Flynn JT. How are hypertensive children evaluated and managed? A survey of North American pediatric nephrologists. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:791–7.

Wühl E, Hadtstein C, Mehls O, Schaefer F, Escape Trial Group. Home, clinic, and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in children with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:492–7.

Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: a report of the american college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2018;71:e13–115.

Kollias A, Ntineri A, Stergiou GS. Association of night-time home blood pressure with night-time ambulatory blood pressure and target-organ damage: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2017;35:442–52.

Stergiou GS, Alamara CV, Salgami EV, Vaindirlis IN, Dacou-Voutetakis C, Mountokalakis TD. Reproducibility of home and ambulatory blood pressure in children and adolescents. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:143–7.

Stergiou GS, Nasothimiou EG, Giovas PP, Rarra VC. Long-term reproducibility of home vs. office blood pressure in children and adolescents: the Arsakeion school study. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:311–5.

Stergiou GS, Giovas PP, Kollias A, Rarra VC, Papagiannis J, Georgakopoulos D, et al. Relationship of home blood pressure with target-organ damage in children and adolescents. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:640–4.

Ntineri A, Zeniodi M, Kollias A, Servos G, Georgakopoulos D, Moyssakis I, et al. Home versus ambulatory blood pressure and target-organ damage in children and adolescents (Abstract). J Hypertens. 2017;35(Suppl 2):e134.

Stergiou GS, Karpettas N, Kapoyiannis A, Stefanidis CJ, Vazeou A. Home blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents: a systematic review. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1941–7.

Stergiou GS, Karpettas N, Panagiotakos DB, Vazeou A. Comparison of office, ambulatory and home blood pressure in children and adolescents on the basis of normalcy tables. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:218–23.

Stergiou GS, Ntineri A. Methodology and applicability of home blood pressure monitoring in children and adolescents. In Flynn JT, Ingelfinger JR, Redwine K, (eds), Pediatric hypertension. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018, 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-31420-4_45-1.

Stergiou GS, Christodoulakis G, Giovas P, Lourida P, Alamara C, Roussias LG. Home blood pressure monitoring in children: how many measurements are needed? Am J Hypertens. 2008;21:633–8.

Stergiou GS, Yiannes NG, Rarra VC, Panagiotakos DB. Home blood pressure normalcy in children and adolescents: the Arsakeion School study. J Hypertens. 2007;25:1375–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

GSS has received lecture fees from Omron. The other authors declare thet they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stergiou, G.S., Ntineri, A., Kollias, A. et al. Home blood pressure monitoring in pediatric hypertension: the US perspective and a plan for action. Hypertens Res 41, 662–668 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0078-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0078-5

This article is cited by

-

Screening and Management of Pediatric High Blood Pressure—Challenges to Implementing the Clinical Practice Guideline

Current Hypertension Reports (2024)

-

Features of and preventive measures against hypertension in the young

Hypertension Research (2019)

-

Home Blood Pressure Monitoring in Children and Adolescents: Systematic Review of Evidence on Clinical Utility

Current Hypertension Reports (2019)