Abstract

Purpose

Alternative models of genetic counseling are needed to meet the rising demand for genomic sequencing. Digital tools have been proposed as a method to augment traditional counseling and reduce burden on professionals; however, their role in delivery of genetic counseling is not established. This study explored the role of the Genomics ADvISER, a digital decision aid, in delivery of genomic counseling.

Methods

We performed secondary analysis of 52 pretest genetic counseling sessions that were conducted over the course of a randomized controlled trial evaluating the effectiveness of the Genomics ADvISER. As part of the trial, participants were randomized to receive standard counseling or use the tool and then speak with a counselor. A qualitative interpretive description approach using thematic analysis and constant comparison was used for analysis.

Results

In the delivery of genomic counseling, the Genomics ADvISER contributed to enhancing counseling by (1) promoting informed dialogue, (2) facilitating preference-sensitive deliberation, and (3) deepening personalization of decisions, all of which represent fundamental principles of patient-centered care: providing clear high-quality information, respecting patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs, and providing emotional support.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that our digital tool contributed to enhancing patient-centered care in the delivery of genomic counseling.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

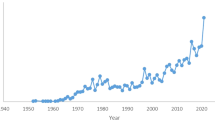

Alternative models of genetic counseling are needed to meet the rising demand for genomic sequencing (GS) across medicine. This demand is emerging in the context of a critical shortage of professionals available to facilitate genomic counseling,1,2,3 a process that incorporates counseling for the multitude of risks that can be revealed by GS and can take hours per patient.4,5,6 Across Canada and the United States, there are approximately 5,500 genetic counselors to serve a population of nearly 400 million, translating to about 1.5 professionals per 100,000 individuals; it is estimated that double this workforce will be needed to meet the increased demand for genomic testing.7,8,9 The unequal distribution of the workforce between urban academic centers and rural regions,8 and the increasing number of counselors transitioning to non-patient-facing roles, such as industry, education, and public policy, further impacts access to qualified professionals.8,10 The limited genomics personnel necessitates alternative and innovative strategies to effectively and efficiently support informed decision-making for GS.11

To address the workforce shortage, there is increasing use of digital tools to support the delivery of counseling across the genomic testing pathway from pretest to post-test counseling, including family history-taking, consent for testing and education.12,13,14 A diverse range of digital tools has been developed including chatbots, digital portals, and software programs.12 Use of these tools in counseling for cancer susceptibility, prenatal anomalies, and carrier status has been shown to improve knowledge and satisfaction, reduce decisional conflict, and initiate deliberative decision-making for patients.14,15 Clinicians report that digital tools are helpful, improve communication of risk information, aid in structuring sessions, and can facilitate patient-centered care,16 a core tenet of genomic counseling practice.6

Despite the increasing need for their use, most digital tools and corresponding research have been limited to the context of counseling for genetic tests such as cancer panels and prenatal screening.10 Tools developed for genomic counseling are limited.13,17 Furthermore, most studies of digital tools have focused on their acceptability and efficacy whereas the impact of digital tools on genomic counseling and facilitating patient-centered care remains unclear.10 The aim of this study was to explore the role of a new digital tool called the Genomics ADvISER,13,18,19 in supplementing genomic counseling with a genetic counselor. Better understanding of the role of digital tools in genetic counseling sessions can optimize their use in practice and health-care delivery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Design

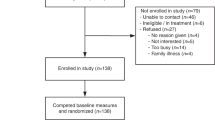

This was a qualitative study employing secondary analysis of transcripts of pretest genetic counseling sessions and was embedded within a randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the effectiveness of the Genomics ADvISER digital decision aid (Fig. 1).13,18 Transcripts of the pretest counseling sessions that were conducted with all study participants are the focus of our analysis. We used qualitative methods because they provide rich data on participants’ experiences, appropriate for understanding the role of the digital tool and its interaction with the genetic counselor in facilitating decision-making for patients.20

The trial has previously been described in detail.13,18 Briefly, participants in the RCT were randomized to either receive standard genetic counseling over the phone (control arm, CTRL) or use the digital decision aid and then have a telephone session with a genetic counselor (intervention arm, INTV) to support secondary finding (SF) decision-making. The intent of the trial was to assess the effectiveness of the decision aid, not response to results; thus, genomic sequencing was not performed, and the decision as to which SFs to receive was hypothetical. The digital tool used by intervention participants guides users through a ten-minute whiteboard video of basic genomic sequencing concepts and five available SF categories followed by brief interactive questionnaires about values, knowledge, and decision-making needs. SF categories included medically actionable results (including pharmacogenomic variants), risks associated with common diseases (polygenic risks), rare Mendelian disorders, early-onset neurological diseases, and carrier status.13

The Research Ethics Boards of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada and The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada approved secondary analysis of the data.

Participants

Participants included all individuals from the trial whose telephone session was audio-recorded with consent. Briefly, inclusion criteria included adults with a personal and/or family history of cancer who had undergone genetic counseling and standard cancer genetic testing in a familial cancer clinic in Toronto, Ontario (single-gene or gene panel testing) with no causative variant identified.13,18

Procedures and data collection

The control sessions modeled pretest genetic counseling for genomic sequencing including an explanation of the SF categories. After completing the decision aid, intervention participants debriefed with a genetic counselor and were offered an opportunity to ask questions. In both arms, each session concluded with the participant being asked to state their hypothetical decision to receive any combination of the five SF categories. The genetic counselor facilitating each session followed a guide to ensure consistency of information provided but also used their training and professional experience to serve participants as they would in a clinical setting. Roughly half of the sessions were recorded. The original purpose for sessions being audio-recorded was for quality control purposes, to check for consistency of content delivery and adherence to the counseling guides. Recording began after ethics approval was obtained, which was about halfway through the trial. Participant characteristics were collected during the trial.13,18 During the consent process, participants consented to allow their data to be used in additional research by the study group. Only de-identified data were accessed for the current study.

Data analysis

Analysis was conducted on audio-recorded telephone sessions between participants and the genetic counselor. All available audio files were reviewed (62); some files were of poor quality and not conducive to transcription (10). In some cases, participants (4) declined to be recorded and their sessions were not available for analysis. All available and good quality audio recordings (52) were facilitated by a single certified genetic counselor (SS). They were transcribed verbatim, most in full, but 11 sessions from the control arm contained minimal verbal contribution from the participant and only those sections were transcribed. Thematic analysis21 employing constant comparison20 was used to analyze the transcripts, with a focus on participants’ verbal content (comments and questions). An interpretive description22 approach was chosen because it is used to examine and understand clinical phenomena with the goal to inform practical applications in clinical settings.23,24 In our case, our goal was to use our findings to inform the use of digital tools to supplement traditional clinical genomic counseling.

Initially, an analysis guide (Supplementary file 1) was created by S.A.R., based on decisional needs as defined in the Ottawa Decision Support Framework.25 S.S. and S.A.R. then listened to the audio files and familiarized themselves with the transcripts, taking notes which briefly summarized each session and documented topics discussed, including those covered by the analysis guide as well as emergent topics introduced by participants. A codebook was developed based on those notes. Transcripts were then read, and codes applied, employing constant comparison to reflect upon previous analysis and iteratively modify codes as necessary. S.A.R. coded all transcripts, with S.S. coding a subset, acting as the second coder for analytic validation. S.A.R. and S.S. met regularly to discuss the process, including resolving any discrepancies in coding through discussion, with documentation made. Both S.S. and S.A.R. undertook a practice of reflexivity prior to and throughout analysis, reflecting upon and documenting their beliefs and assumptions related to the research topic that may influence approach and interpretation.26 Saturation was reached, as the final few transcripts coded from each arm yielded no adjustments to codes or application of previously unused codes.27 The codes and the corresponding quotes were then analyzed, first for the intervention group followed by the control group, to identify patterns in each arm. Patterns that emerged from the intervention and control arm data were then compared to assess similarities, variations, and the extent of those similarities and variations to obtain themes that describe the role of the tool across both arms.

RESULTS

Participant characteristics

A total of 52 sessions were analyzed (21 intervention and 31 control sessions). The majority of participants were female (45/52), of European descent (39/52), born in Canada (34/52), had a university degree (38/52), and were >50 years old (30/52), with about half earning at least $80,000 annually (27/52). Many participants reported a personal (32/52) and/or a family history (50/52) of cancer (Table 1).

The role of digital tools in the delivery of genomic counseling

Our qualitative analysis revealed that the Genomics ADvISER supplemented and enhanced genomic counseling in three ways by (1) promoting informed dialogue, (2) facilitating preference-sensitive deliberation, and (3) deepening the degree of personalization of decisions (Fig. 2). These three functions represent fundamental principles of patient-centered care in the delivery of genomic medicine, namely, providing clear, high-quality information and respecting patients’ values, preferences, and expressed needs.28

Promoted informed dialogue

Participants in the intervention arm were actively engaged in the session after using the digital tool, in that they initiated questions and they offered justification of their selection of SF. Whereas in the control arm, clarification of content was usually led by the genetic counselor, occurred at the end of the session, and participants did not express the same degree of justification for their SF decisions.

For example, intervention participants often initiated questions and clarifications over the course of the session: “If it’s common disease risk, then why should [results] be considered not medically actionable?” (INTV07).

Participants in the intervention arm were also verbally engaged relatively consistently during the session; they asked many questions and actively shared their reflections and justifications for selecting SF with the genetic counselor throughout the interaction.

“Definitely [category] number one, and then, that was the strongest, and then maybe [category] five, but even that would become something that I wouldn’t necessarily want to know now but maybe at some future point, I guess I wouldn’t want to know that much.” (INTV15)

Intervention participants often clarified their options, made real-time decisions, and even changed their SF category selections during the sessions. For example, one participant was hesitant about carrier status results and after clarification of their implications on her son, she elected to receive those results:

“OK, that being the case, I would go ahead and say, yeah, I’ll, in that case, [category] number five, I would go ahead and put that as, one of the ones that I would include in my testing as well.” (INTV16)

This is in contrast to control arm participants, who were more passive recipients of the information and most clarification was genetic counselor–initiated, despite the counselor providing opportunities for questions throughout the session. Strikingly, in nearly half of the control group sessions, the participants made few to no comments during the entire telephone session other than stating their SF category selections at the end when asked to do so. Because the participants did not verbally express their thoughts, the genetic counselor did not have an opportunity to gain insight into their decisional process and needs, including their understanding of the educational content and their considerations for category selections. For example, in a control session that was nearly 50 minutes long, one participant (Table 2, theme 1, CTRL06) asked for clarification about the nature of diseases included in category 5 (carrier status results) in the final 5 minutes of the session, long after the genetic counselor had reviewed that category and provided opportunities for questions. Control arm participants also rarely provided explanation for their selections, with responses such as “I’m across the board yes” (CTRL26) and “I can tell you no, for all of them” (CTRL18) when the genetic counselor asked which categories they would like to receive.

Preference-sensitive deliberation

Participants in the intervention arm engaged in deliberations related to values and perceived harms and benefits and expressed preference-sensitive decisions after using the digital tool. Intervention arm participants discussed a range of benefits and risks of SF, and weighed those benefits and risks to make their decisions, whereas control participants expressed a narrower range of considerations to explain their decisions.

Intervention arm participants verbally deliberated over a wide range of benefits such as “planning, knowing what to expect” (INTV16) and “having enough information to make decisions for myself and my family” (INTV17). Intervention arm participants also discussed a wide array of risks. For example, certain risks associated with SF were mentioned exclusively or nearly exclusively by intervention arm participants. This included fearing the unknown, with participants acknowledging that “once [you] know, [you] can’t unknow [results]: you know you can’t put the cork back in the bottle” (INTV12). Some intervention participants acknowledged other challenges including making SF category selections without knowing the true impact of receiving a positive result and being unsure about “what consequences it might have, in a far-reaching way” (INTV19).

Many participants in the intervention arm also reflected on limitations of GS in their discussion of weighing benefits and risks, stating that “there’s still unanswered questions” (INTV08) and appreciating that genetics “is only one piece of the puzzle” (INTV03). Intervention participants showed deliberation between benefits and risks as illustrated by one participant noting that information about increased risks “can set off stress and anxiety. But, at the same time, it’s a matter of keeping everything in perspective” (INTV01). The nuanced consideration of a broader array of benefits and risks that intervention arm participants grappled with was also characterized by expressions of uncertainty, such as whether the “information is empowering or can it be, at times, kind of, debilitating?” (INTV13).

In contrast, control arm participants reflected on a narrow range of benefits, with one participant noting the benefit of results would be “only for reproductive reasons” (CTRL06). There was less depth to decision-making verbalized by the control arm participants when they were asked for their final selections, as illustrated by one participant selecting all categories and saying that “If I’m already getting all this testing I may as well know everything” (CTRL25). Risks and limitations that control participants reflected on were also not as nuanced. While participants remarked that some results “would be devastating” (CTRL12) and that scientists “don’t know the causes of all diseases” (CTRL30), they did not openly reflect on the implications of these limitations on themselves to the same degree as the intervention participants.

Personalization of decisions

Participants in both arms reflected on GS results in the context of personal experiences and consequences. However, in the intervention arm, participants reflected on a wide range of experiences and consequences, including past genetic testing, personal medical history, family history, life stage, relatives, and legal implications. This is in contrast to control arm participants who provided limited reflections, mostly referencing past genetic testing and their immediate family members. Personal history, particularly cancer history, was frequently referenced by intervention arm participants while making their category selections, including indications that it affected their interpretation of benefits and risks. One participant reflected on the importance of preparation for potential future diseases, stating that she had “already gone through cancer twice.[…] I would rather make the decision or at least prepare for it [another disease]” (INTV05).

Intervention arm participants reflected on feeling prepared to receive results from GS, as they have already “had the genetic testing” (INTV12). In addition to immediate family members, intervention participants reflected on distant relatives and friends as they made their decisions. One participant chose to receive risks for early-onset brain diseases because a cousin of hers that she had a close relationship with developed the disease (Table 2, theme 3, INTV16). One participant who did not have children still considered receiving carrier status, stating, “If I did, it would be for my nieces” (INTV09), while another participant wanted to receive all the results to help provide information for her “grandkids and great grandkids” (INTV07).

Intervention arm participants also acknowledged their category preferences could be different at other stages of their life. One participant stated:

“I feel like the way I answer today might be different from how I would answer it, like you know, a year from now or you know, or maybe how I would have answered it two years ago.” (INTV13)

Intervention participants also reflected on being able to plan their lives better after receiving results, such as making “retirement plans” (INTV07) and “arrangements in terms of insurance” (INTV15).

Overall, the verbal reflections from control participants were not as nuanced, with most participants focusing on their own genetic testing experience and personal cancer history. For example, one participant declined to receive any SF because of a negative experience from past testing, stating that she has since “become hesitant about knowing too much information” (Table 2, theme 3, CTRL18). Reflections about their family were not particularly granular with some electing to receive results to “encourage family members to be tested” (CTRL12) and tended to focus on benefits for immediate relatives only, such as to “help possible children in the future” (CTRL06).

DISCUSSION

The results of our qualitative analysis suggest that the Genomics ADvISER played a role in enhancing the delivery of genomic counseling by (1) promoting informed dialogue, (2) facilitating preference-sensitive deliberation, and (3) deepening personalization of decisions. These functions represent fundamental elements of patient-centered care29,30 and suggest the tool can potentially enhance genetic counseling best practices.6 Overall, participants using the decision aid showed a higher degree of deliberation and verbal engagement in their sessions with the genetic counselor. This provided the genetic counselor with opportunities to respond to the unique perspectives and experiences of each participant, including clarifying misunderstandings and highlighting personal values, consistent with patient-centered care. Overall, this study proposes that use of a digital tool in conjunction with tailored counseling from a genetic counselor can enhance patient-centered care in the delivery of genomic counseling.

Our results are in keeping with findings from previous research. In the context of genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility, implementation of a digital decision aid enabled genetic counselors to personalize session content during pretest counseling.31 Other studies have found that educational content provided prior to pretest genetic counseling was associated with patient assertiveness and promoted shared decision-making.32,33 For patients undergoing genomic counseling, digital tools have been shown to result in greater patient participation34,35 and from our previous trial on the decision aid, reduced time spent with a genetic counselor.13,34,35 Furthermore, studies of digital tools used across multiple decision-making contexts such as prenatal screening for Down syndrome, cancer screening, and preoperative ambulatory surgery, show improved knowledge, self-efficacy, and engagement.36 This is consistent with observations of our study participants, who became more verbally engaged when speaking with the counselor after using the digital tool, perhaps because it allowed them to control their learning15,37 and increase their sense of agency.38 Altogether, our study builds upon the previous literature by demonstrating that digital decision aids can help to foster engagement and promote patient-centered care in an efficient manner in the context of GS, a test for which pretest counseling and informed consent is complicated by the broader range of results than standard genetic tests.29

Our findings suggest that the Genomics ADvISER can be used in conjunction with a genetic counselor in clinical settings to improve the delivery of genomic medicine. The tool can educate and help to empower patients, who would then come to a subsequent counseling session better prepared to engage with the genetic counselor. In turn, the genetic counselors can structure pretest counseling sessions to practice more at the top of their scope, focusing their limited time on psychosocial issues and to explore preferences and values to help patients make informed decisions. This is in contrast to current practices of keeping counseling sessions purposefully vague to account for the thousands of possible genetic conditions that might be revealed.11,39,40 Moreover, this is consistent with recent calls to move genetic counseling away from focusing on extensive educational content about all possible outcomes, usually unattainable and of little relevance or value to patients, and move toward focusing on patients’ social, emotional, and familial context and needs.40 Given these challenges in the current state of practice, the Genomics ADvISER can be used to help efficiently deliver tailored and patient-centered care.

Our study has a few limitations. Although participants and the genetic counselor were instructed to treat the experience as a clinical encounter, no GS was performed and therefore the SF category selections were hypothetical. Intended versus real SF decision-making has been found to differ, and therefore patients’ engagement with counseling may also differ in a nonhypothetical session.41 However, hypothetical trials are recommended by decision support guidance42 as a preliminary means of evaluating a decision aid before trialing the final version of the decision aid in real world settings and a nonhypothetical trial of the Genomics ADvISER is forthcoming.43 The transferability of the results may be limited due to all analyzed sessions being facilitated by one genetic counselor. However, the quality control assessment of the audio files conducted throughout the trial confirmed the genetic counselor followed the guides and encouraged conversation and questions throughout the sessions. Additionally the literature suggests that variability in individual participant verbal contributions can be observed within structured medical encounters, which were also observed in our study.44 Transferability of results may also be limited by the largely homogeneous sample, which consisted mostly of women of European descent with a personal and/or family history of breast cancer who had previously undergone genetic testing and counseling. This sample is reflective of the clinical population presenting for cancer genetics assessment, commonly women referred for testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome; future research in more diverse samples is important. Our study did not include an evaluation of digital literacy, which may play a role in patients’ engagement with the tool. Future studies of digital tools should consider including measures of digital literacy. Finally, the extent of engagement could have been influenced by external factors such as context and the health-care provider.29,45 However, all of the analyzed genetic counseling sessions were facilitated by the same provider, suggesting that the digital tool likely played a role in the observed variability between the control and intervention arm participants. Results from the current study elucidate the mechanism by which the digital tool led to improved patient-centered care, and supports their use in standard genetic counseling practice.

Despite these limitations, these early results provide novel and promising insights into the role of our digital tool in the delivery of genomic counseling through analysis of real-time interactions. In conjunction with a genetic counselor, use of our digital tool fostered informed dialogue, enhanced deliberation and incorporated personal preferences during genomic counseling with research participants. The tool helped to support shared decision-making in an efficient manner, which could be beneficial in research and clinical contexts in which patients are offered genomic sequencing. More broadly, digital decision aids may help foster implementation of patient-centered genomic medicine by providing high-quality information and incorporating patients’ values and preferences within current constraints of health-care personnel and resources. Further research should explore the effectiveness, health outcomes, and costs of using these tools across the full pathway of genomic service delivery.12

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author Y.B. upon request.

References

Boycott, K. et al. The clinical application of genome-wide sequencing for monogenic diseases in Canada: position statement of the Canadian College of Medical Geneticists. J. Med. Genet. 52, 431–437, https://doi.org/10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103144 (2015).

Kalia, S. S. et al. Recommendations for reporting of secondary findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing, 2016 update (ACMG SF v2.0): a policy statement of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics. Genet. Med. 19, 249–255, https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2016.190 (2017).

Phillips, K. A. & Douglas, M.P. The global market for next-generation sequencing tests continues its torrid pace. UCSF. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7528x7p2. (2018).

Bick, D. & Dimmock, D. Whole exome and whole genome sequencing. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 23, 594–600, https://doi.org/10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834b20ec (2011).

Tabor, H. K. et al. Informed consent for whole genome sequencing: a qualitative analysis of participant expectations and perceptions of risks, benefits, and harms. Am J. Med. Genet. 158A, 1310–1319, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.35328 (2012).

Schmidlen, T. et al. Operationalizing the reciprocal engagement model of genetic counseling practice: a framework for the scalable delivery of genomic counseling and testing. J. Genet. Couns. 27, 1111–1129, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-018-0230-z (2018).

Sturm, A. Improving access to genetic counselors under H.R. 3235, the “Access to Genetic Counselor Services Act” of 2019. American Society of Human Genetics. https://www.ashg.org/publications-news/ashg-news/nsgc-hr-3235/ (2020).

Villegas, C. & Haga, S. B. Access to genetic counselors in the Southern United States. J. Pers. Med. 9, 33, https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm9030033 (2019).

Doyle, D. L. Genetic Service Delivery: The Current System and Its Strengths and Challenges. Institute of Medicine (US) Roundtable on Translating Genomic-Based Research for Health. (National Academic Press, Washington, DC, 2009).

Ormond, K. E. et al. Genetic counseling globally: where are we now? Am J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 178, 98–107, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.31607 (2018).

Bernhardt, B. A., Roche, M. I., Perry, D. L., Scollon, S. R., Tomlinson, A. N. & Skinner, D. Experiences with obtaining informed consent for genomic sequencing. Am J. Med. Genet. 167A, 2635–2646, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.37256 (2015).

Bombard, Y. & Hayeems, R. Z. How digital tools can advance quality and equity in genomic medicine. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 505–506, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-020-0260-x (2020).

Bombard, Y. et al. Effectiveness of the Genomics ADvISER decision aid for the selection of secondary findings from genomic sequencing: a randomized clinical trial. Genet. Med. 22, 727–735, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0702-z (2020).

Birch, P. et al. DECIDE: a decision support tool to facilitate parents’ choices regarding genome-wide sequencing. J. Genet. Couns. 25, 1298–1308, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-016-9971-8 (2016).

Birch, P. H. Interactive e-counselling for genetics pretest decisions: where are we now? Clin. Genet. 87, 209–217, https://doi.org/10.1111/cge.12430 (2015).

Glasspool, D. W., Oettinger, A., Braithwaite, D. & Fox, J. Interactive decision support for risk management: a qualitative evaluation in cancer genetic counselling sessions. J. Cancer Educ. 25, 312–316, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-009-0035-8 (2010).

Adam, S. et al. Assessing an interactive online tool to support parents’ genomic testing decisions. J. Genet. Couns. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-018-0281-1 (2018).

Shickh, S. et al. Evaluation of a decision aid for incidental genomic results, the Genomics ADvISER: protocol for a mixed methods randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 8, e021876, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-021876 (2018).

Bombard, Y. et al. The Genomics ADvISER: development and usability testing of a decision aid for the selection of incidental sequencing results. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 26, 984–995, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0144-0 (2018).

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory 2nd edn (Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA, 1998).

Braun, V. & Clark, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 77–101 (2006).

Thorne, S., Reimer Kirkham, S. & MacDonald-Emes, J. Interpretive description: a noncategorical qualitative alternative for developing nursing knowledge. Res. Nurs. Health 20, 169–177 (1997).

Hunt, M. R. Strengths and challenges in the use of interpretive description: reflections arising from a study of the moral experience of health professionals in humanitarian work. Qual Health Res 19, 1284–1292 (2009).

Thorne, S., Reimer Kirkham, S. & O’Flynn-Magee, K. The analytic challenge in interpretive description. Int. J. Qual. Methods 3, 1–11 (2004).

O’Connor, A., Stacey, D. & Boland, L. Introduction to the Ottawa Decision Support Tutorial. https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/ODST/pdfs/ODST.pdf (2015).

Barrett, A., Kajamaa, A. & Johnston, J. How to … be reflexive when conducting qualitative research. Clin. Teach. 17, 9–12, https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13133 (2020).

Saunders, B. et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 52, 1893–1907, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8 (2018).

Tzelepis, F., Sanson-Fisher, R. W., Zucca, A. C. & Fradgley, E. A. Measuring the quality of patient-centered care: why patient-reported measures are critical to reliable assessment. Patient Prefer. Adherence 9, 831–835, https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S81975 (2015).

Epstein, R. M. & Street, R. L. Jr Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, 2007).

Armstrong, M. J., Shulman, L. M., Vandigo, J. & Mullins, C. D. Patient engagement and shared decision-making: What do they look like in neurology practice? Neurol. Clin. Pract. 6, 190–197, https://doi.org/10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000240 (2016).

Green, M. J. et al. Use of an educational computer program before genetic counseling for breast cancer susceptibility: effects on duration and content of counseling sessions. Genet. Med. 7, 221–229, https://doi.org/10.1097/01.gim.0000159905.13125.86 (2005).

Albada, A., van Dulmen, S., Ausems, M. G. & Bensing, J. M. A pre-visit website with question prompt sheet for counselees facilitates communication in the first consultation for breast cancer genetic counseling: findings from a randomized controlled trial. Genet. Med. 14, 535–542, https://doi.org/10.1038/gim.2011.42 (2012).

Wang, C., Gonzalez, R., Milliron, K. J., Strecher, V. J. & Merajver, S. D. Genetic counseling for BRCA1/2: a randomized controlled trial of two strategies to facilitate the education and counseling process. Am J. Med. Genet. 134A, 66–73, https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.30577 (2005).

Lewis, C. et al. Development and mixed-methods evaluation of an online animation for young people about genome sequencing. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 28, 896–906, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0564-5 (2020).

Turbitt, E., Chrysostomou, P. P., Peay, H. L., Heidlebaugh, A. R., Nelson, L. M. & Biesecker, B. B. A randomized controlled study of a consent intervention for participating in an NIH genome sequencing study. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 26, 622–630, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-018-0105-7 (2018).

Jeste, D. V., Dunn, L. B., Folsom, D. P. & Zisook, D. Multimedia educational aids for improving consumer knowledge about illness management and treatment decisions: a review of randomized controlled trials. J. Psychiatr. Res. 42, 1–21., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.10.004 (2008).

Pusic, M. V., Ching, K., Yin, H. S. & Kessler, D. Seven practical principles for improving patient education: Evidence-based ideas from cognition science. Paediatr. Child Health 19, 119–122, https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/19.3.119 (2014).

O’Doherty, K. Agency and choice in genetic counseling: acknowledging patients’ concerns. J. Genet. Couns. 18, 464–474, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-009-9237-9 (2009).

Appelbaum, P. S. et al. Models of consent to return of incidental findings in genomic research. Hastings Cent. Rep. 44, 22–32, https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.328 (2014).

Samuel, G. N., Dheensa, S., Farsides, B., Fenwick, A. & Lucassen, A. Healthcare professionals’ and patients’ perspectives on consent to clinical genetic testing: moving towards a more relational approach. BMC Med. Ethics 18, 47, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0207-8 (2017).

Wynn, J. et al. Impact of receiving secondary results from genomic research: a 12-month longitudinal study. J. Genet. Couns. 27, 709–722, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-017-0172-x (2018).

Coulter, A., Stilwell, D., Kryworuchko, J., Mullen, P. D., Ng, C. J. & van der Weijden, T. A systematic development process for patient decision aids. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 13, S2, https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6947-13-S2-S2 (2013).

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Funding decisions database. https://webapps.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/decisions/p/project_details.html?applId=402559 (2020).

Wade, J., Donovan, J. L., Lane, J. A., Neal, D. E. & Hamdy, F. C. It’s not just what you say, it’s also how you say it: opening the ‘black box’ of informed consent appointments in randomised controlled trials. Soc. Sci. Med. 68, 2018–2028, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.023 (2009).

Street, R. L. & Haidet, P. How well do doctors know their patients? Factors affecting physician understanding of patients’ health beliefs. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26, 21–27, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1453-3 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the following individuals for supporting this study: Simone Newstadt, Laura Winter-Paquette, Kara Semotiuk, Talia Mancuso, Karen Ott, and Leslie Ordal. This research was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the University of Toronto McLaughlin Centre. Y.B. was supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award during this study. S.S. received support from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, GSD-425969) and the Research Training Centre at St. Michael’s Hospital. C.M. received support from the Research Training Centre at St. Michael’s Hospital, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, GSD-164222), and a studentship funded by the Canadian Centre for Applied Research in Cancer Control (ARCC); ARCC receives core funding from the Canadian Cancer Society (grant 2015–703549). Finally, we would like to thank all the participants from the Genomics ADvISER randomized controlled trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.B., S.S., S.A.R., M.C. Formal analysis: S.A.R., S.S., M.C. Project administration: M.C., C.M., S.S. Methodology: Y.B., C.S., D.C., S.S., S.A.R., R.K. Resources: S.P., J.L., T.W., C.E., A.E. Supervision: Y.B., C.S., D.C., M.C., R.K. Writing—original draft: S.A.R., S.S. Writing—review and editing: S.S., S.A.R., M.C., R.K., C.M., S.P., N.W., J.L., T.W., C.E., A.E., J.C.C., E.G., K.A.S., J.L.-E., R.H.K., D.C., C.S., Y.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics declaration

Participants included all individuals from the trial whose telephone session was audio-recorded with consent. The Research Ethics Boards of St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, Canada and The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada approved secondary analysis of the data.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shickh, S., Rafferty, S.A., Clausen, M. et al. The role of digital tools in the delivery of genomic medicine: enhancing patient-centered care. Genet Med 23, 1086–1094 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01112-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-021-01112-1