Abstract

Study Design

Narrative review.

Objectives

Pressure ulcers are a common complication in people with reduced sensation and limited mobility, occurring frequently in those who have sustained spinal cord injury. This narrative review summarises the evidence relating to interventions for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, in particular from Cochrane systematic reviews. It also aims to highlight the degree to which people with spinal cord injury have been included as participants in randomised controlled trials included in Cochrane reviews of such interventions.

Setting

Global.

Methods

The Cochrane library (up to July 2017) was searched for systematic reviews of any type of intervention for the prevention or treatment of pressure ulcers. A search of PubMed (up to July 2017) was undertaken to identify other systematic reviews and additional published trial reports of interventions for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment.

Results

The searches revealed 38 published systematic reviews (27 Cochrane and 11 others) and 6 additional published trial reports. An array of interventions is available for clinical use, but few have been evaluated adequately in people with SCI.

Conclusions

The effects of most interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury are highly uncertain. Existing evaluations of pressure ulcer interventions include very few participants with spinal cord injury. Subsequently, there is still a need for high-quality randomised trials of such interventions in this patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Aetiology and prevalence of pressure ulcers

Pressure ulcers (PUs), sometimes known as pressure injuries, decubitus ulcers or bed sores, are wounds that involve the skin or underlying tissue, or both. They are localised areas of injury occurring most often over bony prominences, such as at the sacrum or heel, where prolonged pressure and sheer forces act to damage tissues and reduce perfusion, causing changes in the tissue and ultimately leading to the wound [1]. PUs are graded according to a number of systems, one widely recognised system being that of the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel [2]. These wounds have a range of serious negative consequences and can severely impair quality of life [3].

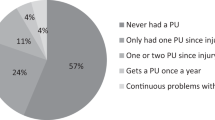

Prevalence estimates vary dependent on the population assessed, the methods of data collection and how a PU is defined (for example, whether stage I PUs are included). It has been estimated that the point prevalence of pressure ulceration in the total adult population is 0.31 per 1000 population [4]. As well as poor perfusion and poor skin status, reduced mobility and autonomic dysreflexia are major risk factors for pressure ulceration [5,6,7,8]. Therefore, people with spinal cord injury (SCI) are a particular group in whom PUs are common due to impaired sensation, reduced mobility and prolonged sitting; a number of studies have estimated the prevalence of PUs among people with SCI, which may be in the range of 30–60% [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Whilst reducing pressure injuries is a major target for many health systems in general, those with SCI are a group at particularly high risk of this complication, and which may be underserved by research evidence.

This article aims to provide an overview of the evidence relating to PU prevention and treatment, in particular drawing on Cochrane systematic reviews since they are widely regarded as rigorous and comprehensive summaries of research [17, 18]. It also aims to assess the degree to which people with SCI have been included as participants in trials of PU interventions.

Interventions for PU prevention and treatment

A wide range of interventions is used in the prevention and treatment of PUs. Key preventative interventions include those which aim to redistribute pressure at the interface between the skin and the support surface (e.g., the many types of mattress and cushion). Key treatment interventions include support surfaces and also wound dressings. The UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence commissioned the National Clinical Guideline Centre to produce a detailed clinical guideline for the prevention and management of PUs in primary and secondary care, which contains a list of interventions used in clinical practice [19]. The main types of intervention are summarised in Box 1.

Systematic reviews

Systematic reviews address clear, focused questions and use systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise all the relevant research. Within a systematic review, data are collected from the included studies, re-presented and frequently re-analysed. Sometimes the data analysis in a systematic review involves combining the results of several separate studies (‘meta-analysis’) to provide a more precise estimate of the effect of an intervention [20]. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews is one source of such reviews.

The aim of this narrative review is to summarise the evidence in relation to the effectiveness of interventions for the prevention and treatment of PUs, in particular from Cochrane systematic reviews. It also aims to highlight the degree to which people with SCI have been included as participants in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of such interventions.

Methods

Systematic reviews of interventions for the prevention and treatment of PUs: search of The Cochrane Library

A range of Cochrane systematic reviews has been undertaken to summarise the current evidence from RCTs of interventions for the prevention and treatment of PUs. A search of The Cochrane Library (Box 2) up to July 2017 revealed 50 results (reviews only), 27 of which are relevant to this review (i.e., they evaluate interventions for the prevention or treatment of PUs; Fig. 1). Of these, 23 reviews evaluate interventions specifically relating to PUs, and 4 relate to several types of chronic or complex wound including PUs. Twenty-one reviews found trials, which were eligible for inclusion, whilst five were ‘empty’ reviews (see ‘Empty reviews’) and another, whilst including various types of wound, did not include any patients with PUs. Of the 50 retrieved results from the search, 23 reviews were not relevant to this overview (i.e., because they focused on other wound types).

Search of PubMed

A search of PubMed was undertaken to determine which other (non-Cochrane) systematic reviews of interventions for PUs specifically in people with SCI had been carried out. The search used the following terms: systematic[sb] AND (((pressure injur*) OR (pressure ulcer*)) AND (spinal cord injur*)). This search revealed eight relevant results (see ‘Other published systematic reviews’); a further three were found using a general Internet search (see ‘Other published systematic reviews’).

A second PubMed search of trials (published results and protocols) using the terms (Therapy/Narrow[filter]) AND (((pressure injur*) OR (pressure ulcer*)) AND (spinal cord injur*)) revealed six trial reports and one trial protocol in addition to those that had been included in Cochrane systematic reviews (see ‘Additional PU trials in people with SCI’).

Results

Prevention of PUs

Five Cochrane reviews that together include 73 RCTs specifically focus on interventions to prevent PUs [21,22,23,24,25] whilst two evaluate interventions for both prevention and treatment of PUs [26, 27]. Table 1 summarises the number of RCTs and participants included in the four prevention reviews for which data were available from the searches undertaken, the main conclusions drawn from these reviews and the quality of the evidence on which they are based (see also ‘Empty reviews’).

It is evident that a very small proportion of participants in the 73 prevention trials covered by the five Cochrane reviews on PU prevention were people with SCI. Just 18 participants from two RCTs [28, 29] included in a review of support surfaces for PU prevention [21] were reported as having SCI out of a total of 12 471 participants across 59 trials in that review (0.14%). None of the other Cochrane reviews of interventions for prevention of PUs included participants with SCI [22,23,24,25], meaning that only 0.12% (18/14 959) participants were affected by SCI across all five prevention reviews. One review of nine trials (1501 participants), which investigated dressings and topical agents for preventing PUs [24] included a trial in which 100 participants underwent posterior spinal surgery [30]. However, those participants underwent surgery for cervical spondylosis, lumbar spinal stenosis, lumbar herniated disc or spinal cord tumour, and so have not been classed here as being participants with SCI.

Treatment of PUs

Sixteen Cochrane systematic reviews assessed the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions for PU treatment [31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], with two others assessing interventions for both prevention and treatment [26, 27]. Table 2 summarises the number of RCTs and participants included in the 14 reviews, which included at least one trial (three reviews that included no trials are described later in ‘Empty reviews’), the main conclusions drawn from these reviews and the quality of the evidence on which they are based.

Across the 14 systematic reviews of treatment interventions there were 145 included RCTs involving 14 166 participants. Only 604 (4.3%) of these participants were described as having SCI (confined to 10 of the trials [47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56]: note that Nussbaum et al. [49] was included in three reviews [31, 43, 57]; Hollisaz et al. [47] was included in two reviews [31, 33]; and Kaya et al. [50] was included in two reviews [31, 34]). Although a trial [58] included in one review [31] did include participants with ‘disorders of the spinal cord’ it was unclear whether these participants had SCI, or how many participants were included.

Systematic reviews investigating interventions for ‘chronic’ or ‘complex’ wounds more generally

In addition to the PU-focussed reviews mentioned above, a further four Cochrane reviews relate more broadly to ‘wounds,’ ‘chronic wounds’ or ‘acute and chronic wounds,’ some of which were PUs.

A systematic review of autologous platelet-rich plasma for treating chronic wounds [59] included 10 trials (442 participants). The Cochrane review concluded that it was unclear whether platelet-rich plasma influences the healing of chronic wounds other than foot ulcers associated with diabetes. Whilst two trials appeared to include two participants with PUs, these were not participants with SCI [60,61,62].

A systematic review of honey as a topical treatment for wounds [57] included a total of 26 RCTs (3011 participants). The review concluded that although honey may speed the healing of partial thickness burns and surgical wounds, its effect on other wounds such as PUs is highly uncertain. Whilst one trial included adult orthopaedic patients with PUs [63], there was no evidence from the review that these were participants affected by SCI.

Dat et al. [64] conducted a systematic review of aloe vera for treating acute and chronic wounds, which included seven trials (347 participants). The review concluded that there was an absence of high-quality evidence from RCTs to support the use of aloe vera (in the form of topical agents or dressings) as a treatment for acute and chronic wounds. One included trial was an RCT, which compared a hydrogel dressing derived from the aloe plant with a saline gauze dressing (applied daily) and included only participants with PUs (n = 41) [65, 66]. However, it is unclear whether this included people with SCI.

Whilst concluding that hyperbaric oxygen therapy may improve the healing of diabetic foot ulcers, a review of 12 trials of this intervention for treating chronic wounds (577 participants) identified none investigating its use in PUs [67].

‘Empty’ reviews

Of the 27 reviews identified by the search of The Cochrane Library, five are ‘empty’ reviews in that the systematic searches undertaken revealed no published data from RCTs. These include reconstructive surgery [44] and repositioning [45] for treating PUs, and bed rest for PU healing in wheelchair users [46]; wound care teams for preventing and treating PUs [26], and massage therapy for prevention [25]. This is somewhat surprising, given that some of these treatments are widely administered to people with SCI.

Whilst no conclusions can be drawn from such ‘empty’ reviews, they can be useful in highlighting the paucity of evidence in these particular areas and perhaps increase their priority as a research topic. This may hopefully lead to high-quality trials being carried out on interventions where there is a theoretical basis that they may work (perhaps informed by existing evidence from non-RCTs). Indeed, the process of systematic reviewing facilitates the provision of some insight into the type of research, which could be undertaken to address a particular problem, for example, in the ‘Implications for research’ section of a systematic review. Specifically, systematic reviews may be able to shed light on what types of patient, intervention, comparison and outcome might be worthy of investigation (known as the ‘PICO’ model). However, despite being updated three times since the initial version, the most recent version of the review on repositioning for treating PUs has still failed to unearth any relevant evidence from RCTs [45]. This possibly implies either that the research community has not been responsive to this important review, or that a high-quality RCT of this type of intervention may be extremely difficult to undertake.

Other published (non-Cochrane) systematic reviews

Of course the evidence synthesised only by Cochrane systematic reviews is not a comprehensive summary of the entire field of PU research. Nor does this review represent all of the studies, which include participants with SCI.

As well as Cochrane systematic reviews, a number of other systematic reviews of interventions for PUs have been published. These include behavioural and educational interventions [68,69,70]; electrical stimulation [71,72,73]; and nutritional support [74]. Others have more broadly assessed a range of interventions for treatment [75, 76] or prevention [77, 78] of PUs within a single review.

Eight of the 11 systematic reviews, which were returned by the search, focussed specifically on people with SCI, which may be an added benefit. Two reviews that included meta-analyses (seven trials, 386 participants [72]; eight trials, at least 302 participants [73]) suggested that electrical stimulation may aid the healing of PUs in people with SCI [72, 73]. However, heterogeneity was shown to be high in the studies included in both of these reviews, which also included at least one non-RCT [72, 73]. An upcoming Cochrane review of electrical stimulation for treating PUs will further add to the evidence base for this intervention [79].

Another review of enteral nutritional support for the prevention and treatment of PUs also included a meta-analysis of five RCTs (1325 participants), but this included studies of patients both with and without SCI [74]. Whilst that review concluded that some oral nutritional supplements were associated with lower incidence of PUs in at risk patients (compared with routine care), a more recent Cochrane review (23 RCTs, 7047 participants) suggested that there is no clear evidence of benefit associated with nutritional interventions for either prevention or treatment of PUs [27].

A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for PUs following SCI provided a narrative summary of a number of studies evaluating wheelchair cushions [76]. The review highlighted evidence that suggests various types of cushion or seating system are associated with potentially beneficial reductions in seating interface pressure or PU risk factors (such as skin temperature) [76]. However, the incidence of new PUs was not included as an outcome in that review, thereby limiting the ability to draw useful conclusions, which may inform clinical practice. A more recent review by Groah et al. [77] focussed on positioning for PUs, and explicitly excluded any studies in which the main outcomes were related to cushion and mattress comparisons (and not the positioning strategies). It is currently unclear as to which types of wheelchair cushion may best prevent pressure ulcers in people with SCI. This is an important area which would benefit from further high-quality research.

The methodological quality of the studies included in some of these reviews was assessed using a variety of methods, with some reviews not providing any quality assessment at all [69, 78]. A further limitation included restrictions on publication language [69, 70, 72,73,74,75,76,77]. The lack of meta-analysis in many reviews limits the conclusions which can be drawn from those reviews with regards to effectiveness.

Upcoming reviews

A number of additional systematic reviews have been registered with the Cochrane Wounds Editorial Base, the protocols for which are currently in the process of being developed, or the reviews themselves undertaken [79,80,81,82,83,84,85] (Table 3). In addition to these, protocols for other (non-Cochrane) systematic reviews have recently been published, which look specifically at interventions for PUs in people with SCI (e.g., self-management interventions to improve skin care for PU prevention [86]).

Additional PU trials in people with SCI

A range of trials of interventions for PUs appears in the published literature, specifically in people with SCI, some of which may not be captured in existing systematic reviews. Preventative interventions include those which involve self-efficacy enhancement [87] and lifestyle management [88, 89], whilst interventions for treatment include irradiation with ultraviolet-C [90], telephone-based support [91] and negative pressure wound therapy [92]. These are clearly candidates for future consideration in systematic reviews and updates.

The rise in use of clinical trial registers, such as the BioMed Central ISRCTN registry, clinicaltrials.gov and the EU Clinical Trials Register, is a particularly welcome practice when determining which trials are in progress. Registration not only allows the clinical and research communities to better plan further trials and systematic reviews (by avoiding unnecessary duplication, reducing research waste and appropriately timing review searches), but it holds investigators to account inasmuch as it publicises up front the aims of the study and its intended outcome measures. This ultimately helps to minimise publication bias when the study is eventually reported [93, 94]. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) [95] brings together much of the published information about past, current and ongoing trials, making this an essential component of the searches for many systematic reviews.

Discussion

This review aimed to summarise the evidence in relation to interventions for the prevention and treatment of PUs, in particular from Cochrane systematic reviews. It is clear from this review that there is a great deal of uncertainty of the effectiveness of such interventions, despite the fact that many are carried out frequently within health services. This review also aimed to highlight the degree to which people with SCI have been included as participants in RCTs of these interventions: this appears to be <3% (for prevention and treatment combined). This seems somewhat counter-intuitive, given that those with SCI are among those at highest risk of pressure ulceration.

It will never be possible for all of clinical practice, in any area, to be based on high-quality research evidence. Therefore, in the absence of good research evidence arising specifically from research in people with SCI, we can learn something indirectly from research in people without SCI, though this is unlikely to be as valid as direct evidence.

It is essential to appraise the quality of research evidence before applying the evidence to people in the clinical setting. In addition to assessing the risk of bias for individual studies, authors of systematic reviews should also grade the quality of the evidence across other domains (such as precision, heterogeneity and directness) for each particular outcome (e.g., healing) across a number of studies using a standardised method such as the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) approach [96]. Together with the use of Summary of Findings tables [97], GRADE enables the reader to interpret the evidence in a more transparent way, helping them to make better informed judgements. Cochrane adopted the use of GRADE in 2011 and its use is encouraged in all new systematic reviews it publishes.

What do Cochrane reviews tell us about PU prevention and treatment?

A large number of interventions are available to clinicians to treat and prevent PUs. Unfortunately, the evidence for many such interventions is often limited, either by the low volume of research or by the quality of the trials which have been undertaken. The best indication from Cochrane systematic reviews of interventions for PUs is that people at high risk of pressure ulceration should use higher-specification foam mattresses, rather than standard hospital foam mattresses, to prevent ulceration. Although Australian medical-grade sheepskins have been identified as potentially useful in the prevention of PUs in people without SCI, they will not be an adequate solution on their own for people with SCI.

Only 16 trials out of a total of 218 included in 18 PU-focussed reviews included participants with SCI. Evidence suggests that approximately only 2% (622/29 125) of included participants were people with SCI, with only four reviews including 30 or more such participants. None of the four reviews relating more broadly to ‘wounds,’ ‘chronic wounds’ or ‘acute and chronic wounds’ appear to have included PU patients with SCI.

The evidence from Cochrane systematic reviews to support use of any other intervention for the prevention and treatment of PUs is currently lacking. Of course, absence of (good quality) evidence does not mean that these interventions are ineffective, just that there effectiveness is not known; it may be that existing research has been too small in scale or at high risk of bias.

Whilst future trials should be undertaken carefully to minimise bias, it is recognised that there is a need for them to remain sufficiently pragmatic to be relevant to clinical practice. A particular challenge for investigators may include the minimisation of performance bias through appropriate blinding.

Prioritisation in PU research

Given the wide variety of interventions available for clinical use to treat and prevent PUs, coupled with the uncertainty of their effects, it is crucial to ensure there is a meaningful way of prioritising future research. The James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) sought to establish research priorities in pressure ulceration by including the views of patients, carers and healthcare professionals. Many of the top priorities identified by that exercise overlap with those questions raised by Cochrane systematic reviews, but where current evidence is unable to draw useful conclusions [98]. The results of this PSP have become a valuable springboard for researchers wishing to improve the evidence base in PU care and it is clear that many of these questions should be addressed in research in people with SCI.

Trials recently identified through a search of trial registers include investigations of text messages for PU prevention in SCI (ISRCTN38320572), a topical wound gel (NCT02001558) and subcutaneous injection and ultrasonic dispersion of cefazolin into chronic PUs in the pelvic region (NCT02584426), among others.

However, it will never be possible to do an RCT for every clinical uncertainty for reasons of resourcing and logistics. Whilst registry data can offer up observational data about the real world effects of alternative interventions [99, 100], there is always the risk of drawing the wrong conclusions because bias and confounding have not been properly acknowledged or accounted for. Indeed, the development of evidence-based, clinical practice guidelines in this field is hampered by the lack of evidence, and recommendations are often based on low-level evidence [101].

In summary, although there is a relatively large volume of primary research on PU prevention and treatment per se, the quality of the evidence results in a lack of direction for practice. Whilst the use of high-specification foam mattresses and medical-grade sheepskins (compared with standard hospital mattresses) may help to prevent PUs in the general population at high risk, the low quality of evidence on which this conclusion is based is likely to mean that the estimate of effect is uncertain and this research will be of low relevance to many people with SCI. It is unclear which type of wheelchair cushion may be beneficial for PU prevention in people with SCI. Furthermore, people with SCI make up <3% of participants included in trials within Cochrane systematic reviews summarising interventions for PUs. Whilst a number of published and ongoing trials specifically in people with SCI have been identified, there is clearly an opportunity to develop further high-quality research in this field in order that promising interventions can be evaluated in this patient group. This may include RCTs, but registry or database studies may also provide useful evidence when high-quality RCTs do not yet exist or are not feasible. However, when it is conducted, future research should be of high quality and address questions that are of high priority to both healthcare providers and people with SCI.

References

Defloor T. The risk of pressure sores: a conceptual scheme. J Clin Nurs. 1999;8:206–16.

The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. NPUAP Pressure Ulcer Stages/Categories. 2016. http://www.npuap.org/resources/educational-and-clinical-resources/npuap-pressure-injury-stages/ (Accessed 6th October 2017).

Spilsbury K, Nelson A, Cullum N, Iglesias C, Nixon J, Mason S. Pressure ulcers and their treatment and effects on quality of life: hospital inpatient perspectives. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:494–504.

Hall J, Buckley HL, Lamb KA, Stubbs N, Saramago P, Dumville JC, et al. Point prevalence of complex wounds in a defined United Kingdom population. Wound Repair Regen. 2014;22:694–700.

Coleman S, Gorecki C, Nelson EA, Closs SJ, Defloor T, Halfens R, et al. Patient risk factors for pressure ulcer development: systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:974–1003.

Marin J, Nixon J, Gorecki C. A systematic review of risk factors for the development and recurrence of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:522–7.

Lindgren M, Unosson M, Fredrikson M, Ek AC. Immobility—a major risk factor for development of pressure ulcers among adult hospitalized patients: a prospective study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2004;18:57–64.

Teasell RW, Arnold JM, Krassioukov A, Delaney GA. Cardiovascular consequences of loss of supraspinal control of the sympathetic nervous system after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:506–16.

Sheerin F, Gillick A, Doyle B. Pressure ulcers and spinal-cord injury: incidence among admissions to the Irish national specialist unit. J Wound Care. 2011;14:112–5.

Lala D, Dumont FS, Leblond J, Houghton PE, Noreau L. Impact of pressure ulcers on individuals living with a spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:2312–9.

Taghipoor KD, Arejan RH, Rasouli MR, Saadat S, Moghadam M, Vaccaro AR, et al. Factors associated with pressure ulcers in patients with complete or sensory-only preserved spinal cord injury: is there any difference between traumatic and nontraumatic causes? J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:438–44.

Nogueira PC, Caliri MH, Haas VJ. Profile of patients with spinal cord injuries and occurrence of pressure ulcer at a university hospital. Rev Lat Am Enferm. 2006;14:372–7.

Richardson RR, Meyer PR. Prevalence and incidence of pressure sores in acute spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1981;19:235–47.

Verschueren JH, Post MW, de Groot S, van der Woude LH, van Asbeck FW, Rol M. Occurrence and predictors of pressure ulcers during primary in-patient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:106–12.

Scheel-Sailer A, Wyss A, Boldt C, Post MW, Lay V. Prevalence, location, grade of pressure ulcers and association with specific patient characteristics in adult spinal cord injury patients during the hospital stay: a prospective cohort study. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:828–33.

van der Wielen H, Post MW, Lay V, Gläsche K, Scheel-Sailer A. Hospital-acquired pressure ulcers in spinal cord injured patients: time to occur, time until closure and risk factors. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:726–31.

Moseley AM, Elkins MR, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Sherrington C. Cochrane reviews used more rigorous methods than non-Cochrane reviews: survey of systematic reviews in physiotherapy. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1021–30.

Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Pham B, Brehaut J, Moher D. Non-Cochrane vs. Cochrane reviews were twice as likely to have positive conclusion statements: cross-sectional study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:380–6.e1.

National Clinical Guideline Centre. The prevention and management of pressure ulcers in primary and secondary care. NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 179. Methods, evidence and recommendations, commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, London, 2014.

Higgins JPT, Green S, (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0: The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane-handbook.org; updated 2011.

McInnes E, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE, Dumville JC, Middleton V, Cullum N. Support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD001735.

Gillespie BM, Chaboyer WP, McInnes E, Kent B, Whitty JA, Thalib L. Repositioning for pressure ulcer prevention in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD009958.

Moore ZE, Cowman S. Risk assessment tools for the prevention of pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD006471.

Moore ZE, Webster J. Dressings and topical agents for preventing pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:CD009362.

Zhang Q, Sun Z, Yue J. Massage therapy for preventing pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD010518.

Moore ZE, Webster J, Samuriwo R. Wound-care teams for preventing and treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011011.

Langer G, Fink A. Nutritional interventions for preventing and treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;6:CD003216.

Economides NG, Skoutakis VA, Carter CA, Smith VH. Evaluation of the effectiveness of two support surfaces following myocutaneous flap surgery. Adv Wound Care. 1995;8:49–53.

Gentilello L, Thompson DA, Tonnesen AS, Hernandez D, Kapadia AS, Allen SJ, et al. Effect of a rotating bed on the incidence of pulmonary complications in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1988;16:783–6.

Han J, Li G, Wang A. Control study on pressure sore prevention for patients accepting posterior spinal surgery. Chin Nurs Res. 2011;25:308–10.

Westby MJ, Dumville JC, Soares MO, Stubbs N, Norman G. Dressings and topical agents for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD011947.

Naing C, Whittaker MA. Anabolic steroids for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD011375.

Han XY, Li HL, Su H, Cai H, Guo TK, Liu R, et al. Topical phenytoin for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD008251.

Norman G, Dumville JC, Moore ZE, Tanner J, Christie J, Goto S. Antibiotics and antiseptics for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD011586.

Aziz Z, Bell-Syer SE. Electromagnetic therapy for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD002930.

Dumville JC, Webster J, Evans D, Land L. Negative pressure wound therapy for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5:CD011334.

Dumville JC, Keogh SJ, Liu Z, Stubbs N, Walker RM, Fortnam M. Alginate dressings for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5:CD011277.

Dumville JC, Stubbs N, Keogh SJ, Walker RM, Liu Z. Hydrogel dressings for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD011226.

Chen C, Hou WH, Chan ES, Yeh ML, Lo HL. Phototherapy for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;7:CD009224.

McGinnis E, Stubbs N. Pressure-relieving devices for treating heel pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD005485.

Moore ZE, Cowman S. Wound cleansing for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD004983.

McInnes E, Dumville JC, Jammali-Blasi A, Bell-Syer SE. Support surfaces for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;12:CD009490.

Baba-Akbari Sari A, Flemming K, Cullum NA, Wollina U. Therapeutic ultrasound for pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD001275.

Wong JK, Amin K, Dumville JC. Reconstructive surgery for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD012032.

Moore ZE, Cowman S. Repositioning for treating pressure ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;1:CD006898.

Moore ZE, van Etten MT, Dumville JC. Bed rest for pressure ulcer healing in wheelchair users. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD011999.

Hollisaz MT, Khedmat H, Yari F. A randomized clinical trial comparing hydrocolloid, phenytoin and simple dressings for the treatment of pressure ulcers [ISRCTN33429693]. BMC Dermatol. 2004;4:18.

Kraft MR, Lawson L, Pohlmann B, Reid-Lokos C, Barder L. A comparison of Epi-Lock and saline dressings in the treatment of pressure ulcers. Decubitus. 1993;6:42–4,46,48.

Nussbaum EL, Biemann I, Mustard B. Comparison of ultrasound/ultraviolet-C and laser for treatment of pressure ulcers in patients with spinal cord injury. Phys Ther. 1994;74:812–23. Discussion 24–5.

Kaya AZ, Turani N, Akyüz M. The effectiveness of a hydrogel dressing compared with standard management of pressure ulcers. J Wound Care. 2005;14:42–4.

Bauman WA, Spungen AM, Collins JF, Raisch DW, Ho C, Deitrick GA, et al. The effect of oxandrolone on the healing of chronic pressure ulcers in persons with spinal cord injury: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:718–26.

Subbanna PK, Margaret Shanti FX, George J, Tharion G, Neelakantan N, Durai S, et al. Topical phenytoin solution for treating pressure ulcers: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:739–43.

Salzberg CA, Cooper-Vastola SA, Perez F, Viehbeck MG, Byrne DW. The effects of non-thermal pulsed electromagnetic energy on wound healing of pressure ulcers in spinal cord-injured patients: a randomized, double-blind study. Ostomy Wound Manag. 1995;41:42–4, 46, 48 passim.

de Laat EH, van den Boogaard MH, Spauwen PH, van Kuppevelt DH, van Goor H, Schoonhoven L. Faster wound healing with topical negative pressure therapy in difficult-to-heal wounds: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;67:626–31.

Brewer RD, Mihaldzic N, Dietz A. The effect of oral zinc sulfate on the healing of decubitus ulcers in spinal cord injured patients. Proc Annu Clin Spinal Cord Inj Conf. 1967;16:70–2.

Ho CH, Bensitel T, Wang X, Bogie KM. Pulsatile lavage for the enhancement of pressure ulcer healing: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92:38–48.

Jull AB, Cullum N, Dumville JC, Westby MJ, Deshpande S, Walker N. Honey as a topical treatment for wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;3:CD005083.

Sebern MD. Pressure ulcer management in home health care: efficacy and cost effectiveness of moisture vapor permeable dressing. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1986;67:726–9.

Martinez-Zapata MJ, Martí-Carvajal AJ, Solà I, Expósito JA, Bolíbar I, Rodríguez L, et al. Autologous platelet-rich plasma for treating chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5:CD006899.

Knighton DR, Doucette M, Fiegel VD, Ciresi K, Butler E, Austin L. The use of platelet derived wound healing formula in human clinical trials. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1988;266:319–29.

Knighton DR, Ciresi K, Fiegel VD, Schumerth S, Butler E, Cerra F. Stimulation of repair in chronic, nonhealing, cutaneous ulcers using platelet-derived wound healing formula. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990;170:56–60.

Anitua E, Aguirre JJ, Algorta J, Ayerdi E, Cabezas AI, Orive G, et al. Effectiveness of autologous preparation rich in growth factors for the treatment of chronic cutaneous ulcers. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2008;84:415–21.

Gulati S, Qureshi A, Srivastava A, Kataria K, Kumar P, Ji AB. A prospective randomized study to compare the effectiveness of honey dressings vs. povidone iodine dressing in chronic wound healing. Indian J Surg. 2014;76:193–8.

Dat AD, Poon F, Pham KB, Doust J. Aloe vera for treating acute and chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD008762.

Thomas D, Goode P, LaMaster K, Tennyson T. Acemannan hydrogel dressing versus saline dressing for pressure ulcers: a randomised, controlled trial. Adv Wound Care. 1998;11:273–6.

Thomas DR, Goode PS, LaMaster K, Tennyson T. Acemannan hydrogel dressing versus saline dressing for pressure ulcers. A randomized, controlled trial. Adv Wound Care. 1998;11:273–6.

Kranke P, Bennett MH, Martyn-St James M, Schnabel A, Debus SE, Weibel S. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for chronic wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;6:CD004123.

Orenczuk K, Mehta S, McIntyre A, Regan M, Teasell R. A systematic review of the efficacy of pressure ulcer education interventions available for individuals with SCI. Can J Nurs Inform. 2011;6.

Gélis A, Stéfan A, Colin D, Albert T, Gault D, Goossens D, et al. Therapeutic education in persons with spinal cord injury: a review of the literature. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;54:189–210.

Cogan AM, Blanchard J, Garber SL, Vigen CL, Carlson M, Clark FA. Systematic review of behavioral and educational interventions to prevent pressure ulcers in adults with spinal cord injury. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:871–80.

Liu LQ, Moody J, Traynor M, Dyson S, Gall A. A systematic review of electrical stimulation for pressure ulcer prevention and treatment in people with spinal cord injuries. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37:703–18.

Liu L, Moody J, Gall A. A quantitative, pooled analysis and systematic review of controlled trials on the impact of electrical stimulation settings and placement on pressure ulcer healing rates in persons with spinal cord injuries. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2016;62:16–34.

Lala D, Spaulding SJ, Burke SM, Houghton PE. Electrical stimulation therapy for the treatment of pressure ulcers in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Wound J. 2016;13:1214–26.

Stratton RJ, Ek AC, Engfer M, Moore Z, Rigby P, Wolfe R, et al. Enteral nutritional support in prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:422–50.

Reddy M, Gill SS, Kalkar SR, Wu W, Anderson PJ, Rochon PA. Treatment of pressure ulcers: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300:2647–62.

Regan MA, Teasell RW, Wolfe DL, Keast D, Mortenson WB, Aubut JA, et al. A systematic review of therapeutic interventions for pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:213–31.

Groah SL, Schladen M, Pineda CG, Hsieh CH. Prevention of pressure ulcers among people with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. PM R. 2015;7:613–36.

Tran JP, McLaughlin JM, Li RT, Phillips LG. Prevention of pressure ulcers in the acute care setting: new innovations and technologies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(3 Suppl):232S–40S.

Arora M, Harvey LA, Glinsky JV, Nier L, Lavrencic L, Kifley A, et al. Electrical stimulation for treating pressure ulcers (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;5:CD012196.

Joyce P, Moore ZEH, Christie J, Dumville JC. Organisation of health services for preventing and treating pressure ulcers (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD012132.

Porter-Armstrong AP, Moore ZEH, Bradbury I, McDonough S. Education of healthcare professionals for preventing pressure ulcers (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD011620.

O’Connor T, Moore ZEH, Dumville JC, Patton D. Patient and lay carer education for preventing pressure ulceration in at-risk populations (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;12:CD012006.

Walker RM, Keogh SJ, Higgins NS, Whitty JA, Thalib L, Gillespie BM, et al. Foam dressings for treating pressure ulcers (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD011332.

Choo J, Nixon J, A. NE, McGinnis E. Autolytic debridement for pressure ulcers (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD011331.

Keogh SJ, Nelson EA, Webster J, Jolly J, Ullman AJ, Chaboyer WP. Hydrocolloid dressings for treating pressure ulcers (Protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD010364.

Baron J, Swaine J, Presseau J, Aspinall A, Jaglal S, White B, et al. Self-management interventions to improve skin care for pressure ulcer prevention in people with spinal cord injuries: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2016;5:150.

Kim JY, Cho E. Evaluation of a self-efficacy enhancement program to prevent pressure ulcers in patients with a spinal cord injury. Jpn J Nurs Sci. 2017;14:76–86.

Clark F, Pyatak EA, Carlson M, Blanche EI, Vigen C, Hay J, et al. Implementing trials of complex interventions in community settings: the USC-Rancho Los Amigos pressure ulcer prevention study (PUPS). Clin Trials. 2014;11:218–29.

Carlson M, Vigen CL, Rubayi S, Blanche EI, Blanchard J, Atkins M, et al. Lifestyle intervention for adults with spinal cord injury: Results of the USC-RLANRC Pressure Ulcer Prevention Study. J Spinal Cord Med. 2017:1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790268.2017.1313931

Nussbaum EL, Flett H, Hitzig SL, McGillivray C, Leber D, Morris H, et al. Ultraviolet-C irradiation in the management of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:650–9.

Arora M, Harvey LA, Glinsky JV, Chhabra HS, Hossain S, Arumugam N, et al. Telephone-based management of pressure ulcers in people with spinal cord injury in low- and middle-income countries: a randomised controlled trial. Spinal Cord. 2017;55:141–7.

Dwivedi MK, Bhagat AK, Srivastava RN, Jain A, Baghel K, Raj S. Expression of MMP-8 in pressure injuries in spinal cord injury patients managed by negative pressure wound therapy or conventional wound care: a randomized controlled trial. J Wound Ostomy Cont Nurs. 2017;44:343–9.

Brown T. It’s time for alltrials registered and reported. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:ED000057.

Brassington I. The ethics of reporting all the results of clinical trials. Br Med Bull. 2017;121:19–29.

Cochrane. Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). 2017. http://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/central-landing-page.html.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, et al. What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336:995–8.

Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Higgins JP, Vist GE, Glasziou P, Guyatt GH. Chapter 11: presenting results and ‘Summary of findings’ tables. In: Higgins JP, Green S, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration. www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Cullum N, Buckley H, Dumville J, Hall J, Lamb K, Madden M, et al. Wounds research for patient benefit: a 5-year programme of research. Program Grants Appl Res. 2016;4:13.

Drolet BC, Johnson KB. Categorizing the world of registries. J Biomed Inform. 2008;41:1009–20.

Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB. Registries for evaluating patient outcomes: a user’s guide. In: Gliklich RE, Dreyer NA, Leavy MB, editors. 3rd ed. 2 Volumes. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014.

Hsieh JM, A, Wolfe D, Lala D, Titus L, Campbell K, Teasell R. Pressure ulcers following spinal cord injury. In: Eng JJ, Teasell RW, Miller WC, Wolfe DL, Townson AF, Hsieh JTC, et al, editors. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation evidence. Version 5.0. 2014. p. 1–90 (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Naomi Shaw (Information Specialist, Cochrane Wounds) for assisting with the search of The Cochrane Library, and to Louise O’Connor (Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Tissue Viability, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust) for her critical reading of the manuscript. The authors (RAA and NAC) of this article were partly funded by the National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (NIHR CLAHRC) Greater Manchester. The funder had no role in the design of the study, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. However, the project outlined in this article may be considered to be affiliated to the work of the NIHR CLAHRC Greater Manchester. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atkinson, R.A., Cullum, N.A. Interventions for pressure ulcers: a summary of evidence for prevention and treatment. Spinal Cord 56, 186–198 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0054-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0054-y

This article is cited by

-

Chitosan hydrogel encapsulated with LL-37 peptide promotes deep tissue injury healing in a mouse model

Military Medical Research (2020)

-

Validity and internal consistency of the French version of the revised Skin Management Needs Assessment Checklist in people with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2018)

-

Summaries of Cochrane Systematic Reviews: making high-quality evidence accessible

Spinal Cord (2018)