Abstract

The aim of this study was to determine if accelerated aging of porcelain veneering had an effect on the surface properties specific to a tetragonal-to-monoclinic transformation (TMT) of zirconia restorations. Thirty-six zirconia samples were milled and sintered to simulate core fabrication followed by exposure to various combinations of surface treatments including as-received (control), hydrofluoric acid (HF), application of liner plus firings, application of porcelain by manual layering and pressing with firing, plus accelerated aging. The quantity of transformed tetragonal to monoclinic phases was analyzed utilized an X-ray diffractometer and one-way analysis of variance was used to analyze data. The control samples as provided from the dental laboratory after milling and sintering process had no TMT (Xm = 0). There was an effect on zirconia samples of HF application with TMT (Xm = 0.8%) and liner plus HF application with TMT (Xm = 8.7%). There was an effect of aging on zirconia samples (no veneering) with significant TMT (Xm = 70.25%). Both manual and pressing techniques of porcelain applications reduced the TMT (manual, Xm = 4.41%, pressing, Xm = 11.57%), although there was no statistical difference between them. It can be concluded that simulated applications of porcelain demonstrated the ability to protect zirconia from TMT after aging with no effect of a liner between different porcelain applications. The HF treatment also caused TMT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A new era in dentistry was introduced because of the unique combination of mechanical and physical properties of zirconia, with fracture toughness being particularly important.1 However, the use of zirconia may be limited by recent reports of chipping of veneering porcelain, which was added primarily for aesthetic reasons. Multiple factors have been proposed to affect the frequency and severity of chipping including mismatch of the thermal expansion co-efficient of the veneering porcelain and the zirconia substructure,2 thickness of the veneering porcelain,3 design of the zirconia framework,4 mechanically defective microstructural regions in the porcelain,5 overloading and fatigue,6 lower flexural strength of the veneering porcelain,7 high cooling rate,3 materials of veneering ceramic, zirconia framework material, and type of surface treatment (e.g. airborne-particle abrasion).8,9

For example, Aboushelib et al. concluded that the bond strength of zirconia and veneering porcelain was lower compared with other ceramic-ceramic systems, which suggested that chipping can be affected by the layering technique of the veneering porcelain.10 Also, Tholey et al.11 found that the application of wet porcelain (porcelain mixed with distilled water) during the veneering process produced a tetragonal-to-monoclinic (t → m) transformation (TMT) at the surface of the zirconia framework. However, there was no transformation when dry porcelain was used. It was concluded that starting with a very thin layer of dry porcelain followed by wet porcelain prevented destabilization of the tetragonal phase at the interface between zirconia and the veneering ceramic. Therefore, a liner could be applied on zirconia to improve the bond strength between the zirconia and porcelain after sandblasting the zirconia core.12 Stoner et al. introduced the discovery of crystalline defects that can form in the porcelain veneering layer when in contact with yttria-stabilized zirconia and the micro-computerized tomographic scanning data showed that yttrium–silicate precipitates were distributed throughout the thickness of the porcelain veneer.13 Furthermore, it has also been shown that the TMT can be triggered by the application of hydrofluoric acid (HF).14

Aging or low-temperature degradation (LTD) is proposed to be another limitation of zirconia when it is exposed directly to the oral environment and that LTD may have a negative effect on the mechanical properties and stability of tetragonal phase as reported by Alghazzawi et al.15 for simulated preparations of zirconia dental restorations. Also, it has been shown that in vivo LTD can be simulated by steam autoclaving at a temperature of 134 °C and a pressure of 0.2 MPa for a period of 5 hours, according to ISO 13356 recommendations.16 Furthermore, the amount of transformed monoclinic phase and thereby the depth of transformation17,18,19,20,21 can be influenced by the aging time22 and measurement techniques.23 Several studies have said that the mechanism(s) of the accelerated, low-temperature TMT is not fully understood.24,25,26

In vivo studies have shown that chipping of the veneering porcelain is the major failure mode for zirconia dental restorations.27,28 The TMT during aging could be a contributory factor for chipping. Thus the incomplete understanding of the effects of (1) firing of veneering porcelain on the zirconia if it can cause TMT at the porcelain–zirconia interface, (2) veneering porcelain on zirconia after aging, and (3) their synergy makes it important to conduct a systematic study of the stability of porcelain veneered tetragonal zirconia under aging conditions.

The objectives of this study were to determine (1) if there is an influence of the layering and pressing techniques on the amount of TMT in the zirconia and (2) if porcelain affects the amount of TMT caused by aging. Quantitative X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to determine both the percentage of transformation and the depth distribution of the monoclinic phase. The effects of thermal exposure and zirconia/porcelain reactions were determined using control samples and removal of the porcelain using HF. The hypotheses were: (1) there will be a difference in the amount of TMT between porcelain layering and pressing of porcelain and (2) veneering porcelain will not prevent the “normal” aging by isolating the zirconia from the moisture.

Materials and methods

Specimen preparation and surface treatments

Thirty-six square-shaped zirconia samples (4 mm thick, 10 mm long, and 10 mm wide) were milled in green stage (presintered form) and sintered (no polish or glaze) simulating core fabrication often used before application of porcelain. The commercial names of all materials and equipment with the corresponding manufacturers are listed in Table 1.

The milled and sintered samples were exposed to various combinations of surface treatments and then distributed into 12 groups as shown in Table 2 with 3 samples per each group. Groups were selected in order to determine the effects of individual and combinations of processing stages. Variables included: (1) HF treatment; (2) exposure to the liner firing temperature (without liner); (3) application of liner; (4) exposure to porcelain application temperature (without porcelain); (5) application of porcelain by manual layering; (6) application of porcelain by pressing; and (7) aging. One group was evaluated without any surface treatment as a control to determine the amount of TMTs as received from the manufacturer (without aging: control group, after aging: Ag group).

The surface treatment with HF alone (HF group) was used to determine the effect of HF on the zirconia surface (amount of monoclinic phase) when this acid is used for dissolving the liner, layered and pressed porcelain followed by exposing the surface of zirconia samples. Furthermore, the treatment of firing at 910 °C was used to determine the effect of this step used during layering and pressing of porcelain on the zirconia samples (amount of monoclinic phase). The ultimate goal was to determine if the TMTs in the zirconia underneath veneering porcelain were related to the aging process, and not caused by HF or/and firing temperature at 910 °C treatments.

Aging process

The aging procedure was done using a steam autoclave aging according to ISO 13356 recommendations;16 however, the aging time was extended for a period of 50 hours to maximize any observed effects.29

Layering of porcelain

The veneering and firing of the veneering materials were performed according to ISO 9693:1999 with the aid of a silicone fixture to achieve standardized thickness of the layered porcelain which was measured using a caliper with accuracy ±0.001 mm. The liner was applied to form a thickness of 0.1 mm. The porcelain application (Vitapan Classical Shade D4) was implemented with a wash- and dentin-firing technique for the initial wetting of zirconia samples. This technique involves the firing of a very thin layer of veneering porcelain with a thickness of 0.5 mm in a furnace chamber. Subsequently, the building up and firing of the dentin porcelain was carried out completed followed by finishing and polishing. The total thickness of the liner and dentin porcelain was adjusted to 2 mm. The firing schedule of the veneering ceramics was as recommended by the manufacturer which was included in Table 3.

Pressing of porcelain

The liner was applied with the same method as layering of porcelain. However, an inlay wax was added onto the zirconia samples. The samples with wax were sprued, invested, and pressed with porcelain (Vitapan Classical Shade D4) according to manufacturer instructions. The total thickness of the liner and dentin porcelain was adjusted to 2 mm.

Hydrofluoric acid surface treatments

All the samples of the groups (except the control, T-Lin, and Ag groups) were immersed in a mini-rubber bowel filled with HF acid for 45 minutes per the manufacturer’s recommendation. The HF acid was changed after the immersion of each group. All surface treatments including liner and porcelain applications were performed on the top surface which was not inscribed, while the (+) symbol was inscribed on the bottom surface using a sharp knife to differentiate the top and bottom surfaces after removal of the liner and porcelain. Since the porcelain on the top surface of the samples was of a darker color (Vitapan Classical Shade D4), this layer was readily delineated and removed by application of the HF acid. Therefore, the top surface of the zirconia was exposed chemically and not subjected to mechanical cutting with a diamond stone that would induce TMT. Assuming that the HF acid application for removal of the porcelain would cause very minimal or no effect on the top surface of the samples as going to be investigated by XRD in this experiment, the data from the aging process should provide reliable and accurate analysis.

X-ray diffraction

The phase distribution was analyzed on the top surface of the samples using an X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation and scans at 40 kV, 30 mA with a step size of 0.004° per step and a scan time of 8 s per step. The TMT was measured on the top surfaces of the samples. A low glancing angle of 3 degrees was used to detect the amount of monoclinic phase with 2θ scans of Bragg–Brentano geometry to be 27°–38°. The monoclinic weight fraction is given by the following equation:

where  and

and  represent the intensity of the monoclinic peaks (2θ = 28° and 2θ = 31.2°, respectively) and

represent the intensity of the monoclinic peaks (2θ = 28° and 2θ = 31.2°, respectively) and  providing the intensity of the respective tetragonal peak (2θ = 30°).30

providing the intensity of the respective tetragonal peak (2θ = 30°).30

The monoclinic volume fraction (Fm) was calculated using the following equation:

The depth of the transformed layer was calculated on the basis of the volume of the m-phase, considering that a constant fraction of grains had symmetrically transformed to m-phase along the surface, as described by Kosmac et al.31

Where θ (=15°) is the angle of reflection, μ (0.064 2 µm−1) is the absorption coefficient and Fm was calculated from Equation 2.

Statistical analysis

The measurements for the three samples per each group were averaged. The number of samples selected per each group in the present study was based on past publications.15 For each of the values, Xm, Fm, and PZT, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed comparing all groups. In each case, a significant P-value of (<0.05) was selected for the ANOVA. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were done for each group one to another using the Tukey’s HSD test. This approach allows adjustment of the P-value for the multiple comparisons.

Results

Description of zirconia peaks

The top of the tetragonal peak  was distorted in most of the samples with widening after the zirconia samples were milled and sintered compared with tetragonal phase (

was distorted in most of the samples with widening after the zirconia samples were milled and sintered compared with tetragonal phase ( )in few samples (control group) as shown in Figure 1.

)in few samples (control group) as shown in Figure 1.

Control group

The control samples (control group) as provided from the dental laboratory after milling and sintering process demonstrated no TMT (Xm = 0.00, Fm = 0.00, PZT = 0.00) as shown in Table 4.

Effect of HF on zirconia

There was an effect of HF application on zirconia samples with TMTs (HF group: Xm = 0.8% ± 1.38%, Fm = 1.04% ± 1.8%, PZT = (0.02 ± 0.04) µm) but with no statistical difference (P > 0.05) when compared to control samples, as shown in Table 4. However, there was no  or

or  peaks on the XRD, but the tetragonal phase (

peaks on the XRD, but the tetragonal phase ( )was wider with similar peak morphology compared with control samples, as shown in Figure 2.

)was wider with similar peak morphology compared with control samples, as shown in Figure 2.

Effect of temperature similar to firing liner (with no liner application)

There was no effect of temperature when tested using conditions similar to firing the liner (with no liner application) (T-Lin group: Xm = 0.00, Fm = 0.00, PZT = 0.00) on zirconia samples compared with control samples, as shown in Table 4. The effect of temperature (similar to firing) for the liner (with no liner application) plus HF application was (T-Lin/HF group: Xm = 0.7% ± 1.2%, Fm = 0.91% ± 1.57%, PZT = (0.02 ± 0.03) µm) on zirconia samples which was very similar to HF applied alone (HF group) on zirconia samples. However, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05), as shown in Table 4.

Effect of liner application on zirconia

There was an effect of liner plus HF applications on zirconia samples related to TMTs (Lin/HF group: Xm = 8.7% ± 4.64%, Fm = 11.06% ± 5.72%, PZT = (0.24 ± 0.13) µm) with a statistical difference (P < 0.05) from T-Lin and T-Lin/HF groups for Xm (P = 0.035 3) and Fm (P < 0.000 1), as shown in Table 4. There was a  peak with no peak on the XRD representing the shifting of tetragonal phase (

peak with no peak on the XRD representing the shifting of tetragonal phase ( ) to a higher 2θ value with a similar peak morphology compared with control samples, as shown in Figure 3. However, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in Xm, Fm, and PZT when the liner was applied compared with samples exposed to temperature similar to firing of porcelain by manual layering (Lin/T-ML/HF group) and pressing (Lin/T-Prs/HF group) techniques. Furthermore, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in Xm, Fm, and PZT when the liner was applied compared with samples covered with porcelain by manual layering (Lin/ML/HF group) and pressing (Lin/Prs/HF group) techniques. There was a similar

) to a higher 2θ value with a similar peak morphology compared with control samples, as shown in Figure 3. However, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in Xm, Fm, and PZT when the liner was applied compared with samples exposed to temperature similar to firing of porcelain by manual layering (Lin/T-ML/HF group) and pressing (Lin/T-Prs/HF group) techniques. Furthermore, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in Xm, Fm, and PZT when the liner was applied compared with samples covered with porcelain by manual layering (Lin/ML/HF group) and pressing (Lin/Prs/HF group) techniques. There was a similar  peak in groups Lin/HF, Lin/T-ML/HF, Lin/ML/HF, Lin/Prs/HF, Lin/T-Prs/HF (bigger peak with Lin/HF group than Lin/T-ML/HF, Lin/ML/HF, Lin/Prs/HF, Lin/T-Prs/HF groups) with no

peak in groups Lin/HF, Lin/T-ML/HF, Lin/ML/HF, Lin/Prs/HF, Lin/T-Prs/HF (bigger peak with Lin/HF group than Lin/T-ML/HF, Lin/ML/HF, Lin/Prs/HF, Lin/T-Prs/HF groups) with no  peak present. The shape of the tetragonal peaks were very similar in all groups (Lin/HF, Lin/T-ML/HF, Lin/ML/HF, Lin/Prs/HF, Lin/T-Prs/HF) related to matter of pyramid and width as shown in Figures 4 and 5.

peak present. The shape of the tetragonal peaks were very similar in all groups (Lin/HF, Lin/T-ML/HF, Lin/ML/HF, Lin/Prs/HF, Lin/T-Prs/HF) related to matter of pyramid and width as shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Comparison of the monoclinic phase between liner application, temperature for pressing (with no porcelain), and temperature for layering porcelain (with no porcelain). There was larger amount of monoclinic phase when the liner was applied (Xm = 8.7%) than samples fired with temperature used for pressing porcelain (Xm = 7.78%) and layering porcelain (Xm = 6.15%) with no porcelain.

Comparison of the monoclinic phase between liner application, pressing porcelain, and layering porcelain with no aging. There was larger amount of monoclinic phase when the liner (Xm = 8.7%) was applied than the samples pressed (Xm = 6.74%) and layered (Xm = 5.58%) with porcelain, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

Effect of aging process on the control group

There was a large effect of the aging process on zirconia samples with significant TMTs (Ag group: Xm = 70.25% ± 0.26%, Fm = 75.58% ± 0.23%, PZT = (2.48 ± 0.02) µm) with statistical difference (P < 0.05) from all other groups for Xm (P < 0.000 1), Fm (P < 0.000 1), and PZT (P < 0.000 1) as shown in Table 4. There was a large  peak with shortening representing the tetragonal phase (

peak with shortening representing the tetragonal phase ( )with a bulbous peak top morphology and appearance of

)with a bulbous peak top morphology and appearance of  peak compared with control samples, as shown in Figure 6.

peak compared with control samples, as shown in Figure 6.

Effect of temperature similar to firing of porcelain using two techniques

There was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in in Xm, Fm, and PZT when different temperatures were utilized representing the firing of porcelain when using manual layering (Lin/T-ML/HF group: Xm = 6.15% ± 1.86%, Fm = 7.90% ± 2.34%, PZT = (0.17 ± 0.04) µm) and pressing (Lin/T-Prs/HF group: Xm = 7.78% ± 3.69%, Fm = 9.93% ± 4.58%, PZT = (0.21 ± 0.1) µm) with no aging process, as shown in Table 4.

There was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in in Xm, Fm, and PZT when the temperature was similar to firing porcelain using manual layering with no porcelain application (Lin/T-ML/HF group) and samples covered with porcelain using manual layering pressing of porcelain samples (Lin/ML/HF group: Xm = 5.58% ± 0.74%, Fm = 7.19% ± 0.94%, PZT = (0.15 ± 0.02) µm) with no aging process, as shown in Table 4. Furthermore, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in in Xm, Fm, and PZT when temperature was similar to firing of porcelain when using pressing with no porcelain application (Lin/T-Prs/HF group) and samples covered with porcelain using pressing (Lin/Prs/HF Group: Xm = 6.74% ± 1.35%, Fm = 8.65% ± 1.7%, PZT = (0.18 ± 0.04) µm) with no aging process, as shown in Table 4.

Effect of porcelain application

There was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in Xm, Fm, and PZT between samples covered with porcelain using manual layering (Lin/ML/HF group) and samples covered with porcelain using pressing (Lin/Prs/HF group) with no aging process, as shown in Table 4. Furthermore, there was no statistical difference (P > 0.05) in the Xm, Fm, and PZT between samples covered with porcelain using manual layering (Lin/ML/Ag/HF group: Xm = 4.41% ± 1.42%, Fm = 5.69% ± 1.81%, PZT = (0.12 ± 0.04) µm) and samples covered with porcelain using pressing (Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group: Xm = 11.57% ± 7.06%, Fm = 14.52% ± 8.57%, PZT = (0.32 ± 0.21) µm) after aging process, as shown in Table 4. There was obvious  and

and  peaks in Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group samples compared with Lin/ML/Ag/HF group samples. The tetragonal peak was longer for Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group samples compared to Lin/ML/Ag/HF group samples with similar width, as shown in Figure 7.

peaks in Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group samples compared with Lin/ML/Ag/HF group samples. The tetragonal peak was longer for Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group samples compared to Lin/ML/Ag/HF group samples with similar width, as shown in Figure 7.

Depth of transformation

There was a statistical difference (P < 0.05) between Ag group vs. all groups (from control group to Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group), between Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group vs. control, HF, T-Lin, T-Lin/HF groups, and between Lin/HF group vs. T-Lin, T-Lin/HF groups for Xm, and Fm. However, the depth of transformation was statistically different between Ag group vs. all groups (from control to Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group), and between Lin/Prs/Ag/HF group vs. control, HF, T-Lin, T-Lin/HF groups only.

Discussion

A tetragonal to monoclinic phase transformation was assessed using a glancing angle of 3° because the highest transformation is located at the surface of zirconia samples and it is decreasing as going inward.15

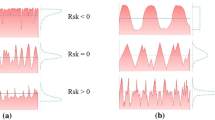

The morphology of the tetragonal peak

There was no benefit to study the TMT on polished zirconia samples because the amount and volume of monoclinic phase was already zero after milling and sintering (control group). However, the difference between the milled, and sintered zirconia samples and polished samples could be in the shape of the top of the tetragonal peak which is distorted. The distortion could be as result of milling and sintering as compared with other literature.15

The effect of hydrofluoric acid on zirconia

There was an effect of HF on the surface properties of this zirconia with little TMT (HF group). Therefore, treatment with HF did not alter the overall results, with all other groups related to removal of the liner and porcelain. These results are in agreement with the study of Sriamporn et al.14 which showed the effect of HF caused surface roughened and etched zirconia which was dependent on immersion time and HF solution temperature. The zirconia samples were not studied after liner application alone without HF because the surface of the zirconia needed to be exposed by the use of HF to detect the TMTs.

Aging process on zirconia

There were no TMTs (Xm and Fm = 0.00) detected in the control group by XRD. However, the Ag group had a very significant TMT (Xm = 70% and Fm = 75%). Therefore, the hypothesis that veneering porcelain will not prevent the “normal” aging by isolating the zirconia from the moisture would be rejected. The main difference in the Xm and Fm on both control and Ag groups was attributed to presence of cracks and defects (on the zirconia surface after milling and sintering) which were formed after milling process. Furthermore, the surface cracks and defects were not eliminated completely by the effect of sintering temperature. These surface cracks and defects could provide a pathway for entrance of water molecules and thereby cause disruption in the atomic network of the zirconia samples.24,25,26 Additionally, the process could be further accelerated by the longer aging time (50 hours). This interpretation is consistent with literature in which the increased aging time can contribute to a higher values of Xm.22

The effect of liner and porcelain on tetragonal to monoclinic transformation

The temperature (1 090 °C) similar to firing of the liner (T-Lin group) did not cause a TMT but application of HF alone (HF group) caused a small TMT. However, when the liner was applied on the zirconia samples combined with HF application (to remove the effect of liner) this caused a significant TMT. This transformation could have been caused by ion exchanges between liner and surface layer of zirconia, especially when the surface was rough after milling and sintering which could have further enhance disruption of zirconia network and result of increased ion exchanges.12 However, when the porcelain was applied by manual layering or pressing, this did not cause any significant opposite monoclinic to tetragonal transformation, therefore, the metastability of zirconia is determined by the type of surface treatment induced on zirconia.32,33 The opposite monoclinic to tetragonal transformation did not happen because the zirconia samples were sealed by the liner and there was no significant difference between the two techniques of porcelain applications. Therefore, the hypothesis that there will be a difference in the amount of TMT between porcelain layering and pressing of porcelain would be rejected. However, future research must be done to study the effect of porcelain application on zirconia with no liner after aging process.

Comparison of Xm and Fm with the literature</emph>

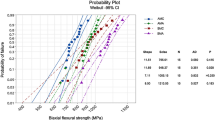

The results in this study (Xm = 0–70.25% and Fm = 0–75.58%) were different from what has been documented because of a difference in measurement instrument23 (XRD vs. Raman Spectroscopy), type of zirconia (yttria-stabilized, magnesia-stabilized, and ceria-stabilized), aging method (autoclaving vs. boiling), aging time, type of glancing angle15 (surface vs. bulk), and surface treatment (heat, sandblasting, grinding).

Depth of transformation

In the present study, the depth of transformation, calculated mathematically from the volume of monoclinic fraction (Fm) as proposed by Kosmec et al.,31 resulted in values that were lower and similar to other studies.20,21 However, when the depth of transformations were measured directly on scanning electron microscopy (SEM), the values were greater than calculated mathematically.17,18,19

A limitation of this study is the surface topography of zirconia grains was not studied by SEM or atomic force microscopy. Future proposed research will include: (1) the correlation of amount of TMT with chipping of porcelain and overall mechanical properties, and (2) comparison of the amount of TMT when the zirconia covered with porcelain and polished/glazed zirconia to determine if there is a difference between covering the zirconia and highly polished/glazed zirconia which are to be used as monolithic zirconia restorations.

Conclusions

-

1

Porcelain demonstrated an ability to protect zirconia substrates from TMT during aging and was no difference between layering and pressing of porcelain in the change to monoclinic phase.

-

2

HF demonstrated etching of zirconia and caused a TMT, but it was not statistically different for the zirconia group after a milling and sintering process.

-

3

There was no effect of a liner on the volume fraction of monoclinic phase and depth of TMT when comparing manual layering and pressing of porcelain.

References

Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ . Evaluation of a high fracture toughness composite ceramic for dental applications. J Prosthodont 2008; 17(7): 538–544.

Fischer J, Stawarzcyk B, Trottmann A et al. Impact of thermal misfit on shear strength of veneering ceramic/zirconia composites. Dent Mater 2009; 25(4): 419–423.

Swain MV . Unstable cracking (chipping) of veneering porcelain on all-ceramic dental crowns and fixed partial dentures. Acta Biomater 2009; 5(5): 1668–1677.

Marchack BW, Futatsuki Y, Marchack CB et al. Customization of milled zirconia copings for all-ceramic crowns: a clinical report. J Prosthet Dent 2008; 99(3): 169–173.

Ohlmann B, Rammelsberg P, Schmitter M et al. All-ceramic inlay-retained fixed partial dentures: preliminary results from a clinical study. J Dent 2008; 36(9): 692–696.

Coelho PG, Silva NR, Bonfante EA et al. Fatigue testing of two porcelain-zirconia all-ceramic crown systems. Dent Mater 2009; 25(9): 1122–1127.

Beuer F, Schweiger J, Eichberger M et al. High-strength CAD/CAM-fabricated veneering material sintered to zirconia copings – a new fabrication mode for all-ceramic restorations. Dent Mater 2009; 25(1): 121–128.

Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ . Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Part II: zirconia veneering ceramics. Dent Mater 2006; 22(9): 857–863.

Aboushelib MN, Kleverlaan CJ, Feilzer AJ . Effect of zirconia type on its bond strength with different veneer ceramics. J Prosthodont 2008; 17(5): 401–408.

Aboushelib MN, de Jager N, Kleverlaan CJ et al. Microtensile bond strength of different components of core veneered all-ceramic restorations. Dent Mater 2005; 21(10): 984–991.

Tholey MJ, Berthold C, Swain MV et al. XRD2 micro-diffraction analysis of the interface between Y-TZP and veneering porcelain: role of application methods. Dent Mater 2010; 26(6): 545–552.

Saka M, Yuzugullu B . Bond strength of veneer ceramic and zirconia cores with different surface modifications after microwave sintering. J Adv Prosthodont 2013; 5(4): 485–493.

Stoner BR, Griggs JA, Neidigh J et al. Evidence of yttrium silicate inclusions in YSZ-porcelain veneers. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 2014; 102(3): 441–446.

Sriamporn T, Thamrongananskul N, Busabok C et al. Dental zirconia can be etched by hydrofluoric acid. Dent Mater J 2014; 33(1): 79–85.

Alghazzawi TF, Lemons J, Liu PR et al. Influence of low-temperature environmental exposure on the mechanical properties and structural stability of dental zirconia. J Prosthodont 2012; 21(5): 363–369.

International Organization for Standardization. International Standard ISO 13356. Implants for surgery—ceramic materials based on yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia (Y-TZP). Geneva: International Organization for Standardization, 2008.

Feder A, Anglada M . Low-temperature ageing degradation of 2.5Y-TZP heat-treated at 1650 °C. J Eur Ceram Soc 2005; 25(13): 3117–3124.

Chowdhury S, Vohra YK, Lemons JE et al. Accelerating aging of zirconia femoral head implants: change of surface structure and mechanical properties. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 2007; 81(2): 486–492.

Ban S, Sato H, Suehiro Y et al. Biaxial flexure strength and low temperature degradation of Ce-TZP/Al2O3 nanocomposite and Y-TZP as dental restoratives. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 2008; 87(2): 492–498.

Amaral M, Valandro LF, Bottino MA et al. Low-temperature degradation of a Y-TZP ceramic after surface treatments. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater 2013; 101(8): 1387–1392.

Souza RO, Valandro LF, Melo RM et al. Air-particle abrasion on zirconia ceramic using different protocols: effects on biaxial flexural strength after cyclic loading, phase transformation and surface topography. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2013; 26: 155–163.

Sanon C, Chevalier J, Douillard T et al. Low temperature degradation and reliability of one-piece ceramic oral implants with a porous surface. Dent Mater 2013; 29(4): 389–397.

Wulfman C, Djaker N, Sadoun M et al. 3Y-TZP In-Depth Phase transformation by raman spectroscopy: a comparison of three methods. J Am Ceram Soc 2014; 97(7): 2233–2240.

Lange FF, Dunlop GL, Davis BI . Degradation during aging of transformation-toughened ZrO2–Y2O3 materials at 250 °C. J Am Ceram Soc 1986; 69(3): 237–240.

Yoshimura M, Noma T, Kawabata K et al. Role of H2O on the degradation process of Y-TZP. J Mater Sci Lett 1987; 6(4): 465–467.

Chevalier J, Gremillard L, Virkar AV et al. The tetragonal–monoclinic transformation in zirconia: lessons learned and future trends. J Am Ceram Soc 2009; 92(9): 1901–1920.

Håff A, Löf H, Gunne J et al. A retrospective evaluation of zirconia-fixed partial dentures in general practices: an up to 13-year study. Dent Mater 2015; 31(2): 162–170.

Güncü MB, Cakan U, Muhtarogullari M et al. Zirconia-based crowns up to 5 years in function: a retrospective clinical study and evaluation of prosthetic restorations and failures. Int J Prosthodont 2015; 28(2): 152–157.

Marro FG, Anglada M . Strengthening of Vickers indented 3Y-TZP by hydrothermal ageing. J Eur Ceram Soc 2012; 32(2): 317–324.

Toraya H, Yoshimura M, Somiya S . Calibration curve for quantitative analysis of the monoclinic-tetragonal ZrO2 system by x-ray diffraction. J Am Ceram Soc 1984; 67(6): C119–C121.

Kosmac T, Wagner R, Claussen N . X-ray determination of transformation depths in ceramics containing tetragonal ZrO2 . J Am Ceram Soc 1981; 64(4): C72–C73.

Kosmac T, Oblak C, Marion L . The effects of dental grinding and sandblasting on ageing and fatigue behavior of dental zirconia (Y-TZP) ceramics. J Eur Ceram Soc 2008; 28(5): 1085–1090.

Wang H, Aboushelib MN, Feilzer AJ . Strength influencing variables on CAD/CAM zirconia frameworks. Dent Mater 2008; 24(5): 633–638.

Acknowledgements

This experiment was supported in part by Deanship of Research, Taibah University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and Matt Winstead, CDT, Vice President, Oral Arts Dental Labs, Huntsville, AL, USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This license allows readers to copy, distribute and transmit the Contribution as long as it is attributed back to the author. Readers may not alter, transform or build upon the Contribution, or use the article for commercial purposes. Please read the full license for further details at - http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Alghazzawi, T., Janowski, G. Evaluation of zirconia–porcelain interface using X-ray diffraction. Int J Oral Sci 7, 187–195 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2015.20

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2015.20

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Influence of different surface treatment on bonding of metal and ceramic Orthodontic Brackets to CAD-CAM all ceramic materials

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

Effect of liner and porcelain application on zirconia surface structure and composition

International Journal of Oral Science (2016)