Abstract

This case report is to present a maxillary first molar with one O-shaped root, which is an extended C-shaped canal system. Patient with chronic apical periodontitis in maxillary left first molar underwent replantation because of difficulty in negotiating all canals. Periapical radiographs and cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) were taken. All roots were connected and fused to one root, and all canals seemed to be connected to form an O-shape. The apical 3 mm of the root were resected and retrograde filled with resin-modified glass ionomer. Intentional replantation as an alternative treatment could be considered in a maxillary first molar having an unusual O-shaped root.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

A thorough knowledge of the external and internal anatomy of teeth is a very important factor in root canal treatment. In many cases, dentists have to deal with various morphological variations. If the dentist fails to detect the morphological variations, it would be a major cause of failure.1 When a preoperative radiograph shows an atypical tooth shape, further radiographic examinations should be considered in order to detect unusual anatomical differences.2 In maxillary first molars, morphological variations,3 such as abnormal numbers of roots, canals,4,5,6,7 fusion and germination and the existence of C-shaped root canals have been widely known.8,9,10

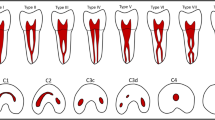

A few cases of C-shaped root canals in maxillary molars have been reported, though C-shaped canals are most frequently found in mandibular second molars.11 Some authors have reported that C-shaped canals result from the fusion of Mesiobuccal (MB) and Palatal (P) roots of maxillary molars, while others have reported that the Distobuccal (DB) and P roots of maxillary molars were fused, and even a case of fusion of the MB and DB roots of maxillary molars was reported.12 The incidence of C-shaped canals in maxillary first molar has been reported to be as low as 0.091% based on radiographic examination.13

In case of anatomical abnormalities, periapical surgery, intentional replantation and even extraction should be considered. Intentional replantation has been performed for more than a thousand years and this technique consists of intentional tooth extraction, cleaning of the apical part of the tooth and reinsertion of the extracted tooth into its own socket immediately.14 Many authors agree that this technique should be the ‘last option’ after all the other procedures have failed or when endodontic periradicular surgery cannot be performed.15 The purpose of this report is to present a morphological variation of C-shaped canal in a maxillary first molar in which the MB, DB and P roots were fused to mimic the letter ‘O’.

CASE REPORT

A 39-year-old male was referred by a private practitioner to the Department of Conservative Dentistry at Yonsei University Dental Hospital. The reason for referral was high possibility of fracture of the maxillary left first molar while trying to remove a pre-existing old post in the palatal canal (Figure 1).

The tooth had been treated endodontically and restored with a post and core 10 years ago. Subsequently, periapical radiolucency developed and the tooth became symptomatic (Figure 2). He had noted previous discomfort intermittently in the upper left molar area. However, he had no symptoms at that point in time. On the clinical examinations, percussion and mobility tests were within normal limits and probing depth was also normal. He had controlled diabetes mellitus.

Based on clinical and radiographic findings, the diagnosis of chronic apical periodontitis was established. The possibility of root perforation by the post and sinus involvement by the roots could not be ignored as the cause of the symptom. For further examination cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT, Rayscan Symphony; Ray Co., Ltd, Seoul, Korea) was performed. CBCT examination revealed a single-rooted maxillary first molar, and all the roots seemed to be fused together into one O-shaped root. The sinus wall seemed to be intact (Figure 3), but the possibility of perforation by the post or root fracture could not be excluded because it was presumed that the existence of an O-shaped root was unlikely at that time and the overlapping of root images were persistent.

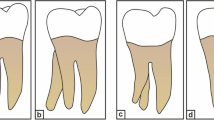

It was concluded that the conventional root canal retreatment was not possible because of difficulty in negotiating all canals and the possibility of root fracture during removal of the post. Hence, intentional replantation was planned. On the day of surgery, patient received a preoperative regimen of antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs. With delicate luxation using a root elevator, the tooth was extracted without fracture. The inflamed granulation tissue in the center of the fused roots was removed meticulously, and one root with an O-shape was observed. On a side view, the root was rectangular in shape, and on an apical view all roots were fully connected and no perforation by the post was observed (Figure 4). When the tooth was examined with a surgical operating microscope (Carl Zeiss OPMI PICO; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), more than five or six small foramina were observed. It was decided to resect the apical end of the root for removing the unnoticed small foramina. The apical 3 mm of the root were trimmed. On the prepared apical O-shaped root surface there were 5–6 root canals with connecting fins, and hence, a 360° circular root end cavity was made with an ultrasonic tip and it was checked by methylene blue (Figure 5). During intentional replantation, the tooth was kept under wet gauze for maintaining the PDL cells of the root surface vital. The root canal was re-cleaned and filled with retrograde root filling material (Resin-Modified Glass Ionomer; fuji II; GC, Tokyo, Japan) to cover the long root end cavity. And the tooth was re-implanted into its own socket. At the 9 months recall visit, the tooth was asymptomatic and a progressive healing of the lesion was evident (Figure 6).

DISCUSSION

We herein present the case of a patient with unusual root morphology of the maxillary first molar which has not been reported up to now. We named this morphological variation as an O-shaped root following the concept of C-shaped roots.

At first, we suspected that this tooth had a C-shaped root16 because a blunt apex and an unclear root shape were seen on the periapical radiographs. Confirmation of the root canal morphology was possible due to the CBCT scanning. The axial and cross-sectional view of the maxillary arch showed the symmetric morphology of the maxillary first molars with an O-shaped root, but we could not exclude the possibility of intimate proximity of roots or simple fusion between the C-shaped root and the other root.

At first, periapical microsurgery was considered for establishing the diagnosis and management of the unusual root morphology. However, the tooth also had difficulties with surgical approaches and the possibility of maxillary sinus perforation during microsurgery.

As a result, intentional replantation was planned carefully because the possibility of tooth fracture could not be excluded. The extraction and replantation procedure was also expected to be difficult because of the rectangular shape of the root. Extraction of the tooth from its socket was done successfully without causing root fracture or alveolar bone fracture, while trying to preserve the periodontal ligament and not exerting too much pressure on the tooth and socket walls.

After removal of the granulation tissue that covered the root from the apical concave area up to the normal furcation area, an O-shaped root was observed. No visible perforation by the post was detected on the root surface, and also no sinus involvement was detected. Because of this inner granulation tissue, the possibility of perforation by the post could not be excluded.

In this case, the extraoral time needed was almost 17 min for meticulous extraction and management of the unusual root morphology. The tooth was kept under wet gauze for maintaining the vital PDL cells. Hammarstrom et al.17 reported that the initial ankylosis did not show when experimental group tooth was treated with the extraoral (complete dry) time of 15 min.17 Therefore favorable prognosis of the tooth was expected.

In recent years, mineral trioxide aggregate has been accepted as the material of choice for root-end filling in endodontic surgery,18 but mineral trioxide aggregate is a technique sensitive material of root end filling for handling in comparison with other materials.19 In this case, resin-modified glass ionomer was selected as a retrograde filling material because it had marginal sealing ability in narrow root end cavity,20 though it was less tissue-tolerant.

Unusual root anatomy of the maxillary molars that has been reported previously includes the fusion of buccal roots, the fusion of MB and P roots, and the fusion of DB and P roots, but to the best of our knowledge this is the first case report of all roots being fused together forming an O-shape with a normal furcation.

In this case, CBCT was useful for diagnosing the unusual root morphology because of its ability to display the serial sections of the tooth. Meticulous examination and recognition of an O-shaped root morphology using periapical radiographs and CBCT could be helpful to diagnose the rare ‘O-shaped root’.

CONCLUSION

The value of this case report was to present maxillary first molar with a very unusual O-shaped root canal system, as such case is seldom mentioned in textbooks. During endodontic therapy, even though the incidence of an O-shaped root is very rare, the recognition with periapical radiographs and CBCT should not be underestimated.

References

Slowey RR . Radiographic aids in the detection of extra root canals. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1974; 37( 5): 762–772.

Fava LR, Dummer PM . Periapical radiographic techniques during endodontic diagnosis and treatment. Int Endod J 1997; 30( 4): 250–261.

Fava LR . Root canal treatment in an unusual maxillary first molar: a case report. Int Endod J 2001; 34( 8): 649–653.

Beatty RG . A five-canal maxillary first molar. J Endod 1984; 10( 4): 156–157.

Cecic P, Hartwell G, Bellizzi R . The multiple root canal system in the maxillary first molar: a case report. J Endod 1982; 8( 3): 113–115.

Bond JL, Hartwell G, Portell FR . Maxillary first molar with six canals. J Endod 1988; 14( 5): 258–260.

Maggiore F, Jou YT, Kim S . A six-canal maxillary first molar: case report. Int Endod J 2002; 35( 5): 486–491.

Dankner E, Friedman S, Stabholz A . Bilateral C shape configuration in maxillary first molars. J Endod 1990; 16( 12): 601–603.

Hartwell G, Bellizzi R . Clinical investigation of in vivo endodontically treated mandibular and maxillary molars. J Endod 1982; 8( 12): 555–557.

Newton CW, McDonald S . A C-shaped canal configuration in a maxillary first molar. J Endod 1984; 10( 8): 397–399.

Fan W, Fan B, Gutmann JL et al. Identification of C-shaped canal in mandibular second molars. Part I: radiographic and anatomical features revealed by intraradicular contrast medium. J Endod 2007; 33( 7): 806–810.

al Shalabi RM, Omer OE, Glennon J et al. Root canal anatomy of maxillary first and second permanent molars. Int Endod J 2000; 33( 5): 405–414.

de Moor RJ . C-shaped root canal configuration in maxillary first molars. Int Endod J 2002; 35( 2): 200–208.

Grossman LI . Intentional replantation of teeth. J Am Dent Assoc 1966; 72( 5): 1111–1118.

Ross WJ . Intentional replantation: an alternative. Compend Contin Educ Dent 1985; 6( 10): 734, 736–739.

Cooke HG 3 rd, Cox FL . C-shaped canal configurations in mandibular molars. J Am Dent Assoc 1979; 99( 5): 836–839.

Hammarstrom L, Blomlof L, Lindskog S . Dynamics of dentoalveolar ankylosis and associated root resorption. Endod Dent Traumatol 1989; 5( 4): 163–175.

Torabinejad M, Parirokh M . Mineral trioxide aggregate: a comprehensive literature review—part II: leakage and biocompatibility investigations. J Endod 2010; 36( 2): 190–202.

Johnson BR . Considerations in the selection of a root-end filling material. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1999; 87( 4): 398–404.

Costa AT, Konrath F, Dedavid B et al. Marginal adaptation of root-end filling materials: an in vitro study with teeth and replicas. J Contemp Dent Pract 2009; 10( 2): 75–82.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a faculty research grant of Yonsei University College of Dentistry (6-2011-0044).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Shin, Y., Kim, Y. & Roh, BD. Maxillary first molar with an O-shaped root morphology: report of a case. Int J Oral Sci 5, 242–244 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2013.68

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijos.2013.68