Abstract

Aim Historically the difficulty of third molar surgery has been judged using radiologically assessed dental factors specifically tooth morphology and position. This study investigated additional factors that have a bearing on the difficulty of extraction.

Study design A prospective study undertaken by three clinical assistant grade surgeons who removed 354 single mandibular third molar teeth under day case anaesthesia over the 4-year period (1994–1998).

Method Data relating to patient, dental and surgical variables were collected contemporaneously as the patients were treated. The difficulty of extraction was estimated by the surgeons pre-operatively using dental radiographic features and compared by the same surgeon within the actual surgical difficulty encountered at surgery. Operation time strongly related to both pre and post treatment assessments of difficulty and proved to be the best measure of surgical difficulty.

Results Univariate analysis identified increased patient age, ethnic background, male gender, increased weight, bone impaction, horizontal angulation, depth of application, unfavourable root formation, proximity to inferior alveolar canal and surgeon as factors increasing operative time. Multivariate analysis showed that increasing age (P = 0.014), patient weight (P = 0.024), ethnicity (P = 0.019), application depth (P = 0.001), bone impaction (p=0.008) and unfavourable root formation (P = 0.009) were independent predictors for difficulty of extraction.

Conclusions Half of the six independent factors that predicted surgical difficulty of third molar extraction were patient variables.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The study was designed to investigate factors associated with the difficulty of mandibular third molar surgery in a representative group of patients undergoing day case surgery.

Surgical removal of mandibular third molars is one of the commonest surgical event, recorded in the NHS costing over £20 million a year mainly as day case or in patient procedures.1 Although previous studies have evaluated the difficulty of surgery by association with complications,2,3 and increased operating time (Table 1)4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 the traditional methods of estimating difficulty have been dominated by dental factors evident on radiological assessment of the dentition. This is reflected in the development of three classification systems based on dental factors (WHARFE-Macgregor 1985, Winters lines-Winter 1926 and Pell & Gregory classification 1933).7,14,15

But opinion varies and some authors believe that surgical complexity cannot be estimated pre-operatively using radiographs but is best done intra-operatively.16 It has been suggested that patient factors also have an important impact on increasing difficulty of third molar surgery; particularly age, gender, size and ethnic background, but only age has been previously linked with increased surgical time and complications.2,3,4,17,18,19,20 At present the emphasis is placed on dental variables when teaching the assessment of difficulty of third molar surgery. For experienced surgeons it is evident that patient variables may also have a strong bearing on the complexity of third molar surgery and this was the impetus for embarking on this study.

The aim of this study was to investigate both patient and operative factors that may predict for the difficulty of mandibular third molar extraction.

Method:

A total of 354 consecutive patients had unilateral lower mandibular third molar tooth removal under day case general anaesthesia at Guy's Dental Institute during a 4-year period (1994–1998). These patients constituted the full spectrum of surgical difficulty as only those with medical problems were directed for inpatient treatment. Ninety-six per cent of these patients had additional extractions or procedures that were not included in the study. Three clinical assistant grade surgeons assisted by training house surgeons using a high-speed sterile hand piece (20,000 rpm) irrigated with sterile water undertook the surgery.

A standardised anaesthetic was provided using Propofol IV induction followed by maintenance using Isoflurane/N2O/O2 via a Laryngeal mask.

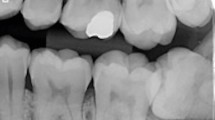

The method of surgery included both buccal and lingual flap approaches (Fig. 1). Contemporaneous collection of data was assisted by a specifically designed database on a local PC network. The definition and mean values that relate to the test variables are shown in Table 2. These are grouped into patient, dental and surgical categories.

Three methods of measuring surgical difficulty for each mandibular third molar were used. The surgeon first judged grades of difficulty pre-operatively using radiographic dental factors (DPTs – using impaction, application depth, angulation and tooth morphology) this was compared with actual surgical experience recorded on the completion of surgery together with duration of operation (operating time = incision to completion of suture for each procedure). The measures of difficulty were assessed by the same surgeon in each case and duration of the procedure by an assistant.

Statistical analysis

Multivariate analysis was used to compare a range of variables representing patient, dental and surgical factors. Using Stata21 these variables were compared individually against operative time as the outcome factor. We took all variables with a univariate P-value of less than 0.1, in order to reduce the number of variables available for the multiple linear regressions. Spearman's correlation coefficient was used to assess correlation between the difficulty assessments. Data were given as mean (SD) and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Over a 4-year study period 354 mandibular third molars were removed in 354 patients and a summary of the variables is presented in Table 2. The definitive measure of operative difficulty was actual surgical experience and was recorded at the end of each case. This strongly correlated with operating time (r = 0.58) which was recorded independently. The correlation of pre-operative assessment of difficulty with operative time was weaker (r = 0.55). Consequently the factors that lead to the pre-operative underestimation of difficulty were evaluated by discrepancies between the pre and post surgery grading scores. The mean operative time was 14.65 minutes and was similar for the 3 surgeons (mean = 14.79, 14.65 and 14.5 minutes) respectively. As operating time strongly correlated with both surgical assessments and is an objective measure this was used as the main outcome measure for evaluation of the relationship of the variables with surgical difficulty.

Many of the factors tested were positive at the univariate level for increased operating time (Table 3). When these were entered into a multivariate analysis dental and patient factors were implicated in surgical difficulty. Dental factors included increased application depth (P < 0.001), unfavourable root formation (P = 0.009), hard tissue impaction (P = 0.008). Patient factors included increased age (P = 0.014), ethnic background (P = 0.019) and increased weight of patient (P = 0.024) and surgeon (P = 0.016) were independent predictors of surgical difficulty.

Threshold values that correlated with increased difficulty of surgery were application depth > 8 mm (P = < 0.04). When the patients were divided into age groups, in this study, to assess where the differences existed those patients over 30 were significantly more difficult than younger patients and the difficulty further increased as the patients age exceeded 50 years (P < 0.05). If the weight of patient exceeded 85 kg the difficulty would also increase markedly (P < 0.05).

Anticipated difficulty of surgery was misjudged in 10% of patients. In 3% of patients the surgery was easier than anticipated and in 7% it was more difficult than expected. The pre-operatively assessed difficulty varied between the three surgeons in that surgeon 1 over or underestimated the surgical difficulty more frequently than surgeons 2 and 3. The most common grade of difficulty was moderate. Factors predictive of underassessment of difficulty using univariate analysis were ethnic background, tooth angulation, bone impaction, depth of application, crown width (exceeding 15 mm on DPT), cheek flexibility, proximity to the inferior dental canal and surgeon 1. Multiple linear regression analysis showed that surgeon 1 (P =0.015) was the only independent predictive factor in underestimation of surgical difficulty (Table 3).

Discussion

Assessment of difficulty of third molar surgery is fundamental to forming an optimal treatment plan in order to minimise complications. A compilation of both clinical and radiological information is necessary to make an intelligent estimate of the time required to remove a tooth.16 Chandler et al. 1988,16 suggested that pre-operative assessment of surgical difficulty was unreliable and the best measure was that made during the procedure. Both measures were used in this study but a post operative measure of difficulty correlated best with duration of surgery, consequently both these measures were used as end points in this study. The difficulty related to each extraction was measured, in order to study the effect of both patient and dental factors that are associated with the difficulty of extraction. The inclusion of bilateral extractions with varying difficulty of extraction caused by dental factors could mask the effect of patient factors.

The methods of estimating difficulty of extraction have been dominated by dental factors evident on radiological assessment of the dentition. Winter14 described three imaginary lines that indicate the depth of the tooth in bone. This method though taught to most undergraduates is used little in daily practice. It was expanded by Macgregor in 1985,7 to WHARFE which includes the Winters lines along with other factors and has recently been used in several studies.17,18 Pell and Gregory15 described an alternative method of assessment of difficulty, also based on dental radiographic features, but this has recently been found to be unreliable22 and of little clinical benefit. Classification of impacted third molars is often an attempt in defining the degree of difficulty of removal; this is generally based on four commonly used classifications of third molars, which are defined by angulation,15 impacted, application depth and eruption. One study13 specifically tested14 radiographic variables in relation to surgical difficulty and found that angulation, relative position of the ramus of mandible to the third molar, application depth, follicle size, periodontal ligament width and relationship to second molar were all predictive of prolonged operating time. By assessing the periodontal width and depth of application a variation in operative time of up to 30% could be predicted. All these studies have in common the fact that pre-operative assessment of surgical difficulty for third molar surgery has focused entirely on dental radiographic features. The present study indicates that three out of six independent predictors of surgical difficulty were related to patient (age, weight and ethnic background) rather than dental factors (increased application depth > 6 mm, bone impaction and root formation).

The minority ethnic group that had more difficult extractions was heterogeneous but comprised of 60% black African or black Carribean ethnicity. When this group was compared directly with the white cohort the difference was not quite significant (P =0.059). Also the mean operative time for white patients was 14.65 mins and for black patients was 17.3 mins. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is that this minority ethnic group may have had more extractions under local anaesthetic, resulting in a biased more difficult group under general anaesthetic, but this was not the case in this cohort of patients. The explanation is unclear but the incidence of bone impaction (P = 0.017), horizontal angulation (P = 0.007), crown width (P = 0.032) and unfavourable root formation (P = 0.003) were significantly increased in this group when compared with the white cohort. Unfavourable root morphology may be linked to other morphological differences such as crown width, which is found to be increased in the Black African groups.23 Another possible explanation is differences in bone density among ethnic groups. This has been shown to be increased in the femoral neck24but has not been studied in the mandible.

Peterson et al.19 also linked increased bone density (measured radiographically) to age and increased surgical difficulty which could account for the positive relationship between increased age and surgical difficulty in this study. Thus the common factor linking increased age, male gender, and minority ethnic background could be alteration in the properties of bone. When the patients were segregated by age, those over 30 were significantly more at risk of difficult extractions than younger patients and the risk increased as the patients age exceeded 50 years (P < 0.05). If this is substantiated, the risk of complications associated with difficult surgery will increase in the elderly group and is evidence to support the argument for early tooth removal.4,20,25,26 Increased patient weight was also associated with surgical difficulty. The mechanism of action is unclear, it is possibly caused by restricted access caused by cheek thickness but a measure of cheek flexibility did not correlate with weight in this study.

Several studies4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 (Table 1) report a varied operative time for third molar surgery from 7.57 to 105 minutes. Duration of surgery depends on a number of factors including surgical difficulty, the experience of the surgeon,27 surgical technique and how the period was measured. The mean operative time of 14.6 minutes for unilateral mandibular third molar removal in this study compared favourably with previous studies. Minimal variation occurred between surgeons presumably reflecting their similarity in grade and case mix of patients.

A prospective study25 investigated and supported the variation in assessment of difficulty within surgeons. Edwards et al. 1998,18 found a poor correlation between the WHARFE index and the surgeons anticipated difficulty. Chandler et al. 1988,16 preferred to assess difficulty during the procedure and felt that experienced surgeons overestimated the surgical difficulty based on radiographic assessment. In only 12% of patients in the present study was there a discrepancy between preoperative assessment and actual difficulty (3% easier and 9% more difficult). One surgeon tended to underestimate surgical difficulty when based on radiological assessment alone. The predictors for underassessment of surgical difficulty at the univariate level were minority ethnic background, surgeon, bone impaction, depth of application, crown width, tooth angulation and proximity to the ID canal.

This study demonstrates that for the experienced operator where simple dental factors may no longer pose a surgical challenge but the presence of adverse patient factors as well as radiological (dental) factors determine the risk of surgical difficulty for the removal of mandibular third molars. The implication is that the relative importance of patient factors should be made when teaching third molar extraction technique and the emphasis removed from dental variable assessments; for example Winter's Lines. This paper also highlights which individual patient and dental factors that are pertinent to the preoperative assessment of surgical difficulty for mandibular third molar surgery.

References

Shepherd J, Brickley M . Surgical removal of third molars. BMJ 1994; 309: 620–621.

Capuzzi P, Montebugnoli L, Antoinetta M . Extraction of impacted third molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1994; 77: 341–343.

Sisk A L, Hammer W B, Shelton D W, Joy E I . Complications following removal of impacted third molars. The role of the experience of the surgeon. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1987; 45:: 15–19.

Bruce R A, Frederickson G C, Small G S . Age of patients and morbidity associated with mandibular third molar surger. J Am Dent Assoc 1980; 10: 240–245.

Chye E P, Young I G, Osborn G A, Rudkin G E . Outcomes after same day oral surgery: a review of 1180 cases at a major teaching hospital. J Oral MaxFac Surg 1993; 51: 846–849.

Vickers P, Goss A N . Day stay oral surger. Aust Dent J 1983; 28: 135–138.

MacGregor A J . The impacted lower wisdom tooth. New York: Oxford University Press; 1985.

Yee K F, Holland R B, Carrick A, Vincent S J . Morbidity following day stay dental anaesthesia. Aust Dent J 1985; 30: 333–335.

Oikarenen K, Rasanen A . Complications of third molar surgery among university students. Coll Health 1991; 39: 281–285.

Absi E G, Shepherd J P . A comparison of morbidity following the removal of lower third molars by the lingual split and surgical bur methods. Int J Oral Maxfac Surg 1993; 22: 149–153.

Berge T I, Gillhuus-Moe O T . Per and post operative variables of mandibular third molar surgery by four general practitioners and one oral surgeon. Acta Odontol Scand 1993; 51: 389–397.

Berge T I, Boe O E . Predictor evaluation of postoperative morbidity after surgical removal of mandibular third molars. Acta Odontol Scand 1994; 52: 162–169.

Santamaria J, Arteagoitia I . Radiologic variables of clinical significance in the extraction of impacted mandibular third molars. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997; 84: 469–473.

Winter G B . Principles of exodontia as applied to the impacted third molar. St Louis: American Medical books; 1926.

Pell G J, Gregory G T . Impacted third molars: Classification and modified technique for removal. The Dent Digest 1933: 330–338.

Chandler L P, Laskin D M . Accuracy of radiographs in classification of impacted third molar teeth. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1988; 46: 656–660.

Edwards D J, Shepherd J P, Horton J, Brickley M . Impact of third molar removal on demands for postoperative care and job disruption: Does anaesthetic choice make a difference. Ann Roy Coll Surg Eng 1999; 81: 119–112.

Edwards D J, Brickley M, Horton J, Edwards M J, Shepherd J P . Choice of anaesthetic and healthcare facility for third molar surger. Br J Oral Maxfac Surg 1998; 36: 333–340.

Peterson L J, Ellis E III, Hupp J R . Contemporary Oral Maxillofacial Surgery. (ed 2). St Louis, MO, Mosby, 1993, 237–249.

Chiapasco M, Pedrinazzi M, Motta J, Crescentini M, Ramundo G . Surgery of the lower third molars and lesions of the lingual nerve. Minerva Stomatologica 1995; 45: 517–522.

Stata statistical software, Release 5.0. Texas: College Station, Stata Corporation, 1997.

Garcia A G, Sampedro F G, Rey J G, Vila P G, Martin M S . Pell–Gregory classification is unreliable as a predictor of difficulty in extracting impacted lower third molars. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2000; 83: 585–587.

Otuyemi O D, Noar J H . A comparison of crown size dimensions of the permanent teeth in a Nigerian and British population. Eur J Orthodont 1996; 18: 623–628.

Harris S S, Eccleshall T R, Gross C, Dawson-Hughes B, Feldman D . The vitamin D receptor start codon polymorphism (Foki) and bone mineral density in premenopausal American black and white women. J Bone & Mineral Res 1997; 12: 1043–1048.

Nordenram A . Post operative complications in oral surgery. A study of cases treated during 1980. Swed Dent J 1983; 7:: 109–113.

Goldberg M H, Nemarich A N, Marco II W . Complications after third molar surgery. A Statistical analysis of 500 consecutive procedures in private practice. J Am Dent Assoc 1985; 111:: 277–279.

Handelman S C, Black P M, Gatlin L, Simians L . Removal of impacted third molars by oral/maxillofacial surgeons and general dentist residents. Spec Care Dent 1993; 13: 122–126.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank our surgical colleagues in the Department of Oral & Maxillofacial Surgery of Guy's Dental Institute for allowing us to use their patient data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Renton, T., Smeeton, N. & McGurk, M. Factors predictive of difficulty of mandibular third molar surgery. Br Dent J 190, 607–610 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801052

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.4801052

This article is cited by

-

Mandibular third molar extraction: perceived surgical difficulty in relation to professional training

BMC Oral Health (2023)

-

A deep learning model based on concatenation approach to predict the time to extract a mandibular third molar tooth

BMC Oral Health (2022)

-

Salivary Cortisol as a Stress Monitor During Third Molar Surgery

Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery (2022)

-

Black Lives Matter: the impact and lessons for the UK dental profession

British Dental Journal (2021)

-

Deep learning based prediction of extraction difficulty for mandibular third molars

Scientific Reports (2021)