Abstract

Background:

Pressure ulcers are a common secondary condition that occur post-spinal cord injury (SCI). These ulcers come at tremendous personal and societal cost. There are a number of scales that can be used to identify those who are at risk.

Objectives:

This review critically evaluates risk assessment scales designed for identifying and predicting skin ulcers. Specifically, studies on the psychometric properties and utility for individuals with SCI were assessed.

Methods:

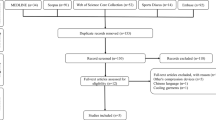

The MedLine, CINHAL, Embase, HaPI, Psycinfo, Sportdiscus and Cochrane databases were searched to identify studies. To be included, the scale needed to have at least one study, published in a peer-reviewed journal, which examined its psychometric properties with a sample of individuals with SCI.

Results:

Seven scales were included in this review: Abuzzese, Braden, Gosnell, Norton, SCIPUS, SCIPUS-A and Waterlow. None of the tools reported reliability data with this population. Validity evidence ranged from poor to adequate across scales. Most were readily available, quick to administer and had minimal respondent burden; however, the SCIPUS-A and SCIPUS, two scales developed specifically for individuals with SCI, required laboratory blood testing.

Conclusion:

Although the SCIPUS-A and SCIPUS show promise, utility issues and limited psychometric testing suggest that these tools cannot be recommended at this time. While the Braden scale has the best combined validity and utility evidence, more specific testing with individuals with SCI is required for it and all other scales included in the review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) experience a variety of long-term secondary medical complications. Pressure ulcers, defined as an area of localized damage to the skin and underlying tissue caused by pressure, shear, friction and/or a combination of these (European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, 2007) (Accessed March 7 from http://www.epuap.org/gltreatment.html), are one of the most serious and frequent of these problems.1, 2 These chronic wounds can have harmful personal3, 4 and societal effects.5, 6

Pressure ulcers are extremely common in individuals with SCI. It is estimated 85% of individuals with SCI will experience a pressure ulcer during their lifetime.7 McKinley et al.2 found that pressure ulcers were the most common secondary medical complication of SCI with prevalence rates ranging from 15.2% 1 year after injury to 29.4% at 20 years after injury. Chen8 reported a trend toward increasing pressure-ulcer prevalence in recent years, which is not explained by aging, years since injury or demographic variables.

The medical costs associated with the treatment of pressure ulcers are high. Treatment cost is proportional to the severity of the ulcer, because the healing rate is slower and likelihood of complications is greater.5 The total cost for treating pressure ulcers is estimated to be 8.5 billion dollars in the United States9 and between 1.4 and 2.1 billion pounds in the United Kingdom, which represents 4% of that country's total health budget.5 The cost of pressure-ulcer treatment in Spain represents 5.2% of the total health-care expenditure.10 It is estimated that the cost of treating pressure ulcers for individuals with SCI may represent one-quarter of their total cost of care.11

Pressure ulcers have a serious impact on the individual and those around them. Qualitative research has identified that pain is a key feature.3, 4 As well, pressure-ulcer treatment often necessitates long-lasting activity modifications and restrictions that can have a negative psycho-social impact on the individuals and their families.3, 4 Other sequellae include social isolation, alteration of body image, lost income, odor and drainage.6 In some individuals, pressure ulcers may prove fatal.12

A large number of risk and protective factors for the development of pressure ulcers have been described for individuals with SCI. Some of the risk factors that have been identified include: being underweight,13 smoking,13, 14 lower level of activity,14, 15 incontinence,14, 15 pulmonary disease,14, 15 decreased albumin,14, 15 decreased mobility,14, 15 extent of paralysis,14, 15 increasing age,14 use of medications for sleep,16 impaired cognitive function,14 diabetes,14 living in a hospital or nursing home,14 spasticity,14 renal disease,14 and low hematocrit.14 Protective factors identified include completing a college degree,13 being married,13 being employed,13 exercise16 and healthy diet.16

Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers following SCI advocate the use of risk assessments, which include many of the preceding risk factors, to improve practice in this area.17 Nixon and McGough18 identified over 38 such risk assessment instruments. Despite the abundance of available tools, very few have been tested psychometrically18 especially with individuals with SCI.

It is essential to validate tools with their intended population(s), because validity is not an innate property of a test, but instead represents the evidence that supports the interpretation of the test scores.19 Tools should be assessed within specific populations,20 because a measure that is reliable with one patient group may be unreliable with another. Moreover, measures intended for one population may lack content validity when used with a different population.21 For example, pressure-ulcer risk factors for elderly individuals are often different from those with SCI.22 Finally, in terms of utility, an instrument that is relatively easy to administer with one population may be difficult to administer with another. The purpose of this review was to critically evaluate pressure-ulcer risk assessment tools in terms of their reliability, validity and utility for individuals with SCI.

Methods

A review of pressure-ulcer risk assessment scales used with individuals with SCI was systematically conducted. To be included, measures had to have been assessed in at least one study published in a peer-reviewed journal that examined the psychometric properties of the instrument using a sample of individuals with SCI. Study-specific scales designed for intervention trials were not included in this review, because they are difficult for researchers and clinicians to obtain and frequently use an alternate method of calculating reliability co-efficients than would be used with tools intended for a variety of users.23 Additionally, only papers written in English were considered.

Search strategy

MedLine, CINHAL, Embase, HaPI, Psycinfo, Sportdiscus and Cochrane electronic databases were searched (1986 to January 2007) to locate papers describing these measures. Additional searching was conducted by reviewing the references of papers obtained from the electronic search. The key word ‘spinal cord injury’ was used across each of the databases, while the following terms varied depending on the database used: validation studies, instrument validation, external validity, internal validity, criterion-related validity, concurrent validity, discriminant validity, content validity, face validity, predictive validity, reliability, interrater reliability, intrarater reliability, test–retest reliability, reproducibility, responsiveness, sensitivity to change, evidence-based medicine, outcome measures, clinical assessment tools, scales, measures, pressure ulcer, decubitus, pressure sore and pressure wound. A database file was established using RefWorks to organize potential articles of interest. After eliminating duplicate papers two trained data extractors reviewed each title to determine which abstracts should be reviewed then the abstracts were reviewed to determine which papers should be extracted. When disagreement occurred, a third extractor was consulted to break any ties.

Assessing the tools

Data were extracted from papers by a team of reviewers using a data extraction form designed to record the reliability, validity, interpretability, feasibility and acceptability of the tool items. The methods and standards of data extraction were based on the work of Fitzpatrick et al.24 Using the criteria noted in Table 1, the psychometric and utility properties reported for each tool were summarized as excellent, adequate or poor. ‘Excellent’ indicated that the tool was outstanding in regard to that criteria, ‘poor’ indicated that serious deficiencies were noted and ‘adequate’ indicated the ‘tool rates somewhere in between’25 (p. S15). For example, a validity score of excellent corresponded to correlations above 0.60 with similar measures or convergent constructs. Respondent burden was considered excellent if administration time was brief (<15 min) and the measure was well accepted by persons with disabilities. Interpretability was considered excellent if the tool was easy to administer, score and interpret. When validity correlations varied across studies (for example, poor in one study and adequate in another), results were summarized as a range (for example, poor—adequate).

Results

Our review identified four studies that provided validity evidence for seven tools that have been tested with individuals with SCI. All of these studies used retrospective data extracted from medical records to determine each subject's risk assessment scale score and presence of pressure ulcers. The measures in these studies included the Abruzzese,27 Braden,28 Gosnell,29 Norton,30 SCIPUS,14 SCIPUS-A15 and Waterlow.31 A brief overview of each instrument is provided in Table 2. The Norton, created in 1962, is the original pressure-ulcer risk assessment tool and served as a template for many other scales.18 Overall, the measures cover between 5 and 8 domains. The domains of mobility, activity and continence are common across all measures and nutrition (or albumin level) is a domain in six of the seven scales. The SCIPUS tool has the most items,15 including many unique items such as autonomic dysreflexia and living setting. The SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A also include items that require laboratory tests of albumin levels, serum creatinine and blood glucose. The SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A were developed exclusively for individuals with SCI using regression analysis to identify variables, collected via retrospective chart review that predicted pressure-ulcer development.14, 15 Although the risk factors considered for inclusion were not described for the SCIPUS,14 over 50 potential pressure-ulcer risk factors were evaluated for the SCIPUS-A of which 21 were explicitly described.15 Those factors included age, tobacco use, alcohol history, nutritional support, level of activity, mobility, mental status, urinary continence, nutritional status, moisture, ‘friction and shear’, and 10 laboratory blood work variables.15 For the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A, the same data were used to generate the scale and to test their validity.14, 15

For all scales, items are scored using item-specific descriptive criteria, but the amount of detail provided varies considerably across measures. The Norton and Waterlow provide the least detailed scoring instructions. Both offer only one or two word descriptions for each score. For instance, in the Norton, the domain of physical condition is illustrated by four descriptors ‘Good 4, Fair 3, Poor 2, Very Bad 1’30 (p. 225). In contrast, with the Braden,28 the tool that provides the most complete operational definitions, a score of 1 for the domain of sensory perception is described as ‘Completely limited: unresponsive to painful stimuli, either because of either unconsciousness or severe sensory impairment, which limits ability to feel pain over most of body surface’ (p. 206). The Abruzzese, SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A measures fall in between, in that although most items are well operationalized, items such as moisture and extent of paralysis for the SCIPUS-A and impaired cognitive function for the SCIPUS are not.

The validity evidence for these instruments is described in Table 3. This includes sensitivity and specificity, area under the curve (AUC), which measures how well the test predicts who will and will not develop a skin ulcer, construct and concurrent validity results. In light of differences in study populations, the psychometric data are presented on per study basis. Validity results tended to vary across studies and between measures. The Braden had the best AUC,33 but poor construct validity in terms of stage of first pressure ulcer (r=0.03) and conflicting concurrent validity with the Norton (r=0.48) and Waterlow (r=−0.06) scales.32 The AUCs ranged from 81% for the Braden to 72% for the Norton.33

In terms of utility, a number of characteristics are common across measures, as noted in Table 4. All of the scales are available for free either electronically on the World Wide Web or from the original articles in which they were published. Most authors do not indicate that training is required to use the measure, although training for the Braden is suggested.28 A video-taped manual is available for the Braden scale.

All scores are easily calculated by hand based on scoring criteria provided by their authors. For all scales, a total score is computed by adding item scores together. For most scales, higher scores indicate increased risk of developing a pressure ulcer, although for the Braden and Norton, the scoring is reversed and lower scores are indicative of higher risk. For the Norton, Braden, Gosnell and Abruzzese scales, scores are consecutive (1, 2, 3, 4 and so on) and one score per domain is allowed. The scoring is slightly more complicated for the SCIPUS, SCIPUS-A and Waterlow. For the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A scale, scores are weighted for all domains (for example, extent of paralysis is scored as 0=none, 1=paraparesis, 4=quadriparesis, 8=paraplegia and 10=quadriplegia). These weighted values were based on the relative value coefficients (rounded for simplicity) from a logistic regression model of factors associated with pressure ulcers in individuals with SCI.15 For the Waterlow most items are weighted, and for many, multiple response categories can be selected. For example, when describing skin type as a risk factor, an individual could have ‘dry’ (=1), ‘oedematous’ (=1) and/or ‘discoloured’ (=2) skin leaving an item-based score ranging from 1 to 4. As with the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A, scores for each item are not consecutive, but no rationale for the weighting scheme is described.

A summary of the psychometric and utility evidence, according to the Andresen's criteria (Table 1)25 is provided in Table 5. Validity evidence for all the measures ranged from adequate to poor. As all measures took less than 15 min to complete, and were generally non-invasive, most were deemed excellent in terms of their respondent burden. The exceptions were the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A, which require blood tests. As response descriptions for at least some of the items in most measures were vague, administrative burden was found to be only adequate for all measures except the Braden, which was rated as excellent because of its detailed scoring guidelines.

Discussion

This review identified seven measures that had been tested with individuals with SCI. These included (1) three of the most commonly used and validated scales for pressure-ulcer prediction in the general population (the Braden, Norton and Waterlow);10, 32 (2) two measures designed specifically for individuals with SCI during acute hospitalization (SCIPUS-A)15 and rehabilitation (SCIPUS)14 and (3) two lesser known and validated scales (the Abruzzese and the Gosnell).

The finding that no reliability testing has been conducted in the SCI population for all measures reviewed is a concern, albeit not unexpected. In their systematic review of risk assessment scales in other populations, Pancorbo-Hidalgo et al.10 identified 12 measures that had been validated using controlled clinical trials or prospective cohort studies. They found no reliability data for 7 of the 12 scales included in their systematic review. Pearson's reliability coefficients for the Braden ranged from 0.83 to 0.99 across 13 studies in different settings (nursing homes, home care and hospital) and populations (orthopedics, geriatric and intensive care). In the three studies that examined the reliability of the Waterlow and Norton scales, reliability scores of r=0.99 and % of observer agreement of 92.5 and 100% were reported, respectively. Because of their inclusion criteria,10 however, no studies with individuals with SCI were part of this review. Generalizability Theory indicates that these results cannot be applied to individuals with SCI,34 which undermines confidence in these scales to reproduce stable results over time with this population.

Given that over 200 risk factors for developing a pressure ulcer have been reported for individuals with SCI,22 it is important to identify which ones need to be included in a measure to ensure adequate content validity. Although all of the measures included pressure-ulcer risk factors that have been identified for individuals with SCI,22 the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A were the only instruments developed exclusively for individuals with SCI. The items included in these measures indicate that important risk factors in the general population are not the same for individuals with SCI during different phases of their recovery.15 The use of linear regression to identify items for the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A is a strength of these measures, but the limited description of what variables were evaluated makes it difficult to determine if all important variables were considered.

A total of four studies looked at the validity evidence of these measures for individuals with SCI. Overall, no scale demonstrated excellent validity based on the published criteria used in this review.25, 26 Validity evidence for the Abruzzese and Gosnell was reported in only one study and results were poor.15 Validity evidence for the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A was reported in two studies with adequate results. The SCIPUS-A had the best sensitivity and specificity, and construct validity of all measures tested for individuals during acute hospitalization, although the Waterlow was not included in this study.15 Similarly, the SCIPUS had good sensitivity and specificity for individuals during rehabilitation,14 but no comparisons were made between other instruments, so no definitive conclusions can be drawn. The sensitivity and specificity of the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A scores may be inflated, because these scales were developed and tested using the same retrospective data. These scores would likely decrease, if the measure was tested again with a different sample. Validity evidence for the Braden, Waterlow and Norton was reported in three studies with mixed results. Although the AUC was adequate for all of these measures,33 the Braden and Norton had poor construct validity32 and the concurrent validity of the Braden and Waterlow was poor.32

Most measures were similar in terms of their utility. With the exception of the SCIPUS, all measures consisted of only eight items or less, so the administration time was very similar. For all instruments, the measure and scoring criteria are available for free and training was only recommended for the Braden scale. Subject burden for most tests is minimal unless results of blood tests are not already available, in which case, the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A would involve additional respondent burden and might add administrative burden. For instance, in a community setting, administration of the SCIPUS would require a physician to order blood testing and either the individual to visit a laboratory, or have home testing arranged, all of which would add substantially to the direct and indirect cost of this measure. The Braden scale offers the best operationalization of response categories, while response descriptions for at least some of the items from other scales were vague. For example, with the SCIPUS-A raters are to indicate whether the patient experiences moisture rarely, occasionally, very often or constantly; these frequencies are not quantified, however, which may lead to misclassification. Better operationalization of the responses would permit clinicians to extract more useful information.

Comparing the validity results of this review with those obtained by Pancorbo-Hidalgo et al.10 reveals some interesting similarities and differences. The weighted means of sensitivity and specificity of the Braden (57.1 and 67.5%, respectively) noted by Pancorbo-Hidalgo et al. are somewhat similar to the sensitivity and specificity noted by Salzberg et al.15 for individuals with acute SCI (sensitivity 74.7% and specificity 56.6%). The sensitivity and specificity of the Norton (46.8 and 61.8%), however, are markedly different (sensitivity 5.8% and specificity 95.6%). These comparisons emphasize the need for population-specific psychometric testing.

The retrospective method used to evaluate validity in all of the studies in this review is a concern. Given problems with the accuracy and completeness of medical records,35 a retrospective analysis of medical data may not represent a true picture of either the patient's ulcer severity or risk for developing an ulcer.

Recommendations

This review highlights the difficulties inherent in the selection of a pressure-ulcer risk assessment scale for individuals with SCI. Although the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A have the advantage of being specifically tailored to individuals with SCI and their sensitivity and specificity results are good, they are limited by their lack of reliability data, and the fact that validity testing was conducted with the same data used for their development. Consequently, the use of SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A cannot be recommended without further psychometric testing. Given that the Braden scale performed similarly to the SCIPUS-A in testing, had the largest AUC33 and, generally, was the most well-validated instrument;10 the Braden scale seems to be best tool currently available, although it would also benefit from additional testing with individuals with SCI.

A variety of future studies are suggested by the findings of this review. Obviously, all of these measures require reliability testing with individuals with SCI. As well, prospective studies that allow head-to-head comparison of these risk assessment scales would represent a far more robust method to evaluate their concurrent and construct validity. The use of multiple regression analysis to identify scale items seems promising, but all of the factors that are evaluated need to be identified explicitly, as other factors, including psychological factors, socioeconomic status, existence of a previous skin ulcer and etiology of the SCI, may be more critical risk factors for individuals with SCI than for individuals from other populations.22 Because of how these tools are used in clinical settings, responsiveness studies are required and more importantly, studies that evaluate the effectiveness of these tools for pressure-ulcer prevention are needed. Such studies would provide a critical element of validity that is missing among these tools in identifying individuals at risk of developing a pressure ulcer and preventing their occurrence. This is especially important, given that Keast et al.36 in their review of best practice recommendations for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, found only level four evidence (expert opinion) supported the use of validated risk assessment tools for the prevention of pressure ulcers.

Limitations

This review included only, peer-reviewed studies written in English. Although a variety of search terms were employed, it is possible that some studies may not have been included in the review, as gray literature, conference abstracts and studies published in other languages were not accessed.

Conclusion

This review identified seven pressure-ulcer risk assessment tools that had been validated with individuals with SCI. Reliability and responsiveness evidence for individuals with SCI was absent in the literature. Validity results indicate that five of the measures demonstrate adequate validity and two are poor. Although the SCIPUS and SCIPUS-A are promising scales, the Braden seems to be the best tool currently available. Given the importance of healthy skin to individuals and the personal and societal costs of pressure ulcers, further research is vital to evaluate the psychometric properties of these instruments and determine their effectiveness in pressure-ulcer prevention and treatment.

References

Noreau L, Proulx P, Gagnon L, Drolet M, Laramee MT . Secondary impairments after spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 79: 526–535.

McKinley WO, Jackson AB, Cardenas DD, DeVivo MJ . Long-term medical complications after traumatic spinal cord injury: a regional model systems analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1999; 80: 1402–1410.

Langemo DK, Melland H, Hanson D, Olson B, Hunter S . The lived experience of having a pressure ulcer: a qualitative analysis. Adv Skin Wound Care 2000; 13: 225–235.

Hopkins A, Dealey C, Bale S, Defloor T, Worboys F . Patient stories of living with a pressure ulcer. J Adv Nurs 2006; 56: 345–353.

Bennett G, Dealey C, Posnett J . The cost of pressure ulcers in the UK. Age Ageing 2004; 33: 230–235.

Langemo DK . Quality of life and pressure ulcers: what is the impact? Wounds 2005; 17: 3–7.

Günnewicht BR . Pressure sores in patients with acute spinal cord injury. J Wound Care 1995; 4: 452–454.

Chen Y, Devivo MJ, Jackson AB . Pressure ulcer prevalence in people with spinal cord injury: age-period-duration effects. Arch Phy Med Rehabil 2005; 86: 1208–1213.

Allman RM . Epidemiology of pressure sores in different populations. Decubitus 1989; 2: 30–33.

Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, Garcia-Fernandez FP, Lopez-Medina IM, Alvarez-Nieto C . Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2006; 54: 94–110.

Houle RJ . Evaluation of seat devices designed to prevent ischemic ulcers in paraplegic patients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1969; 50: 587–594.

Redelings MD, Lee NE, Sorvillo F . Pressure ulcers: more lethal than we thought? Adv Skin Wound Care 2005; 18: 367–372.

Krause JS, Vines CL, Farley TL, Sniezek J, Coker J . An exploratory study of pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: relationship to protective behaviors and risk factors. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001; 82: 107–113.

Salzberg CA, Byrne DW, Cayten CG, van Niewerburgh P, Murphy JG, Viehbeck M . A new pressure ulcer risk assessment scale for individuals with spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1996; 75: 96–104.

Salzberg AC, Byrne DW, Kabir R, van Niewerbugh P, Cayten CG . Predicting pressure ulcers during initial hospitalisation for acute spinal cord injury. Wounds: a Compendium of Clinical Research and Practice 1999; 11: 45–57.

Krause JS, Broderick L . Patterns of recurrent pressure ulcers after spinal cord injury: identification of risk and protective factors 5 or more years after onset. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 1257–1264.

Garber S, Biddle A, Click C, Cowell JF, Gregorio-Torres TL, Hansen NK . Pressure ulcer prevention and treatment following spinal cord injury: a Clinical Practice Guideline for Health Care Professionals. J Spinal Cord Med 2000; 24: S40–S101.

Nixon J, McGough A . Principles of patient assessment: screening for pressure ulcers and potential risk. In: Morison MJ (ed). The Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers. Mosby: Toronto, ON, 2001, pp 55–74.

Messick S . Validity of psychological assessment: validation of inferences from Persons' responses and performances as scientific inquiry into score meaning. Am Psychol 1995; 50: 741–749.

Atkinson G, Nevill AM . Statistical methods for assessing measurement error (reliability) in variables relevant to sports medicine. Sport Med 1998; 26: 217–238.

Streiner DL, Norman GR . Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press: New York, 2003.

Byrne DW, Salzberg CA . Major risk factors for pressure ulcers in the spinal cord disabled: a literature review. Spinal Cord 1996; 34: 255–263.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL . Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86: 420–428.

Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR . Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technol Assess 1998; 2: i–iv, 1–74.

Andresen EM . Criteria for assessing the tools of disability outcomes research. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000; 81 (12 Suppl 2): S15–S20.

McDowell I, Newell C . Measuring Health. A Guide to Rating Scales and Questionnaires. Oxford University Press: New York, 1996.

Abruzzese RS . Early assessment and prevention of pressure sores. In: Lee BY (ed). Chronic Ulcers of the Skin. McGraw Hill: New York, 1985, pp 1–19.

Bergstrom N, Demuth PJ, Braden BJ . A clinical trial of the braden scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Clin North Am 1987; 22: 417–428.

Gosnell DJ . An assessment tool to identify pressure sores. Nurs Res 1973; 22: 55–59.

Norton D, Maclaren R, Exton-Smith AN . An investigation of Geriatric Nursing Problems in Hospital: National Corporation for the Care of Old People. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh, Scottland, 1962.

Waterlow J . Pressure sores: a risk assessment card. Nurs Times 1985; 81: 49–55.

Wellard S, Lo SK . Comparing Norton, Braden and Waterlow risk assessment scales for pressure ulcers in spinal cord injuries. Contemp Nurse 2000; 9: 155–160.

Ash D . An exploration of the occurrence of pressure ulcers in a British spinal injuries unit. J Clin Nurs 2002; 11: 470–478.

Portney LG, Watkins MP . Foundations of Clinical Research. Applications to Practice. Appleton & Lange: Stamford, CN, 1993.

Pringle M, Ward P, Chilvers C . Assessment of the completeness and accuracy of computer medical records in four practices committed to recording data on computer. Br J Gen Pract 1995; 45: 537–541.

Keast D, Parslow N, Houghton P, Norton L, Fraser C . Best practices for the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: Update 2006. Wound Care Can 2006; 4: 31–43.

Acknowledgements

Salary support for Dr Miller was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Mr Mortenson's work was supported by a Strategic Training Fellowship in Rehabilitation Research from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Musculoskeletal and Arthritis Institute, the Canadian Occupational Therapy Foundation and graduate fellowships from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. Funding for this project was provided by the Rick Hansen Man in Motion Research Foundation and the Ontario Neurotrauma Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mortenson, W., Miller, W. & the SCIRE Research Team. A review of scales for assessing the risk of developing a pressure ulcer in individuals with SCI. Spinal Cord 46, 168–175 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102129

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102129

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Risk constellation of hospital acquired pressure injuries in patients with a spinal cord injury/ disorder - focus on time since spinal cord injury/ disorder and patients’ age

Spinal Cord (2023)

-

Development of the spinal cord injury pressure sore onset risk screening (SCI-PreSORS) instrument: a pressure injury risk decision tree for spinal cord injury rehabilitation

Spinal Cord (2021)

-

Severe pressure ulcers requiring surgery impair the functional outcome after acute spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2020)

-

The Spinal Cord Injury Pressure Ulcer Scale (SCIPUS): an assessment of validity using Rasch analysis

Spinal Cord (2019)

-

Validity and internal consistency of the French version of the revised Skin Management Needs Assessment Checklist in people with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2018)