Abstract

Study design:

Case report.

Objective:

To describe the difficulty in diagnosing spinal pseudomeningocoele.

Setting:

Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, University of Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

Case report:

A case of progressive sacral swelling in a paraplegic man who sustained spinal cord injury 14 years ago is presented. Although his clinical features were suggestive of pseudomeningocoele, we were unable to confirm the diagnosis preoperatively.

Conclusion:

Traumatic spinal pseudomeningocoele is very rare. Even with the available modern diagnostic imaging techniques, it is still difficult to diagnose a spinal pseudomeningocoele.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traumatic pseudomeningocoele following injury to the spinal cord is a rare condition. The presence of dural tear is necessary for its formation; the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) will flow through the dural tear and subsequently an extradural collection of CSF is formed.1 It can appear weeks to years after the injury and most cases are asymptomatic. All reported cases were confirmed by radiological techniques.

Case report

A 39-year-old paraplegic man with conus medullaris syndrome following traumatic spinal cord injury in 1992 complained of progressive swelling over the sacral area for the past 9 months. Three months before presentation, the swelling has begun to affect his sitting posture associated with symptoms of radiculopathy. There was also ulceration of the skin overlying the swelling. However, there was no fever, change in size of swelling with sneezing and coughing, or deterioration of neurological and functional status.

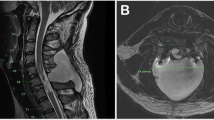

The described swelling is shown in Figure 1. The size was approximately 9.5 cm in diameter, non-tender, transilluminate and irreducible upon pressure.

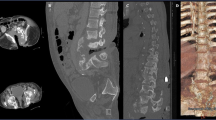

Fluid aspirate from the swelling revealed altered blood, which was non-clotting in nature leading to the suspicion of CSF. Microscopic examination showed packed red cells. The culture specimen was negative. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the sacral region showed a well-defined swelling at the lower sacral region lined with fibrous tissue. There was extravasation of fluid to the surrounding soft tissue, but there was no clear indication of a connection with the spinal canal. Three-dimensional MRI constructive interference in steady state and computerized tomography myelogram also failed to demonstrate such a connection.

The provisional diagnosis was simple cystic swelling with organizing haematoma. The patient was scheduled for removal of cyst in September 2004. Intra-operatively, the swelling was found to be a pseudomeningocoele with a patent fistula. It was resected and the fistula ligated. Postoperatively he developed surgical wound breakdown, which was partly due to faecal contamination. A diversion colostomy was performed to aid healing. There has been no recurrence of swelling till the last outpatient review in March 2006.

Discussion

Couture and Branch1 described spinal pseudomeningocele as an abnormal collection of CSF that results from dural tear and can be lined by an arachnoid-lined membrane or fibrous capsule. Retrospectively, our patient had several features that supported the diagnosis right from the time of presentation. However, with negative radiological results, we were unable to confirm the diagnosis.

The presence of a mid-line fluctuant mass overlying the previous scar at the sacral region should lead to a high index of suspicion.1 Back pain radiating to the lower limb may occur in pseudomeningocoele.2, 3 Schumacher et al3 believed that the pain is due to oscillating CSF flow in the fistula with the spinally directed stream irritating the nerve root. The pain can be due to nerve root entrapment or herniation into the pseudomeningocoele. Progressive neurologic dysfunction in a spinal cord injured patient has been reported as the presenting symptom of pseudomeningocoele.1

It is clearly seen in this patient that it was difficult to objectively prove the connection between the swelling and the spinal canal. Beta-2 transferrin test can confirm that the fluid aspirated is CSF.4 Unfortunately, the test is not available in our hospital. Considering that this condition is rare, it is unlikely that this test would be performed routinely. The presence of CSF in the swelling will definitely point to the diagnosis of pseudomeningocoele even if there is no radiological evidence of connection with the spinal canal.

MRI was our first choice of investigation as it provides superior soft tissue imaging with much information about fluid characteristics.1 It is also useful if the treatment plan includes surgical intervention. Three-dimensional MRI constructive interference in steady state used in this patient was supposed to provide a better refinement to MRI.5 In addition to MRI, computerized tomography scan has also been widely used to diagnose pseudomeningocoele.2 In the absence of computerized tomography and MRI, myelography can be used to identify pseudomeningocoele.2 There will be extravasation of the dye from the spinal canal into the swelling. However, the communication between these two spaces has to remain open to permit the dye to enter. If the communication is closed, it may give a false-negative finding. Rapid communication is only found in a quarter of patients, and a delayed film (after 24 h) should be obtained if the initial film is negative.2 This however was not carried out in this patient.

Optimal management of pseudomeningocele depends on size, location and severity of symptoms. Both surgical and non-surgical approaches have good results. In this patient, it was unfair to manage the pseudomeningocele conservatively. First, the swelling has caused development of a pressure ulcer. The swelling was affecting his sitting posture, and as he is wheelchair-dependent, most of his activities had to be carried out in sitting position. Therefore the condition was disabling him progressively. Second, skin breakdown could lead to infection with risk of the central nervous system involvement. Third, the patient had pain that could lead to further disability.

Conclusion

Traumatic spinal pseudomeningocele is a rare condition. This case is unique because we were unable to diagnose it preoperatively despite the extensive radiological investigations.

References

Couture D, Branch CL . Spinal pseudomeningocele and cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. Neurosurg Focus 2003; 15 Available at http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/466999.

Teplik JG, Peyster RG, Teplick SK, Goodman LR, Haskin ME . CT identification of postlaminectomy pseudomeningocele. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1983; 140: 1203–1206.

Schumacher HW, Wassman H, Podlinski C . Pseudomeningocele of the lumbar spine. Surg Neurol 1988; 29: 77–78.

Ryall RG, Peacock MK, Simpson DA . Usefulness of beta-2 transferrin in the detection of cerebrospinal fluid leaks following head injury. J Neurosurg 1992; 77: 737–739.

Ramli N, Cooper A, Jaspan T . High resolution CISS imaging of the spine. Br J Radiol 2001; 74: 862–873.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Julia, P., Nazirah, H. Spinal pseudomeningocoele: a diagnostic dilemma. Spinal Cord 45, 804–805 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102116

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3102116