Key Points

-

Provides a summary of the available literature on leaving teeth on open drainage as part of endodontic treatment.

-

Shows that a proportion of general dental practitioners use open drainage as a treatment option for teeth associated with pain and/or infection.

-

Highlights the importance of gathering information regarding current general dental practice in order to better target future practice, teaching and research.

Abstract

Objective There is a need to ascertain the use of evidence-based dentistry in both primary and secondary care in order to tailor education. This study aims to evaluate the use of 'open drainage' as part of endodontic treatment in primary care in South Yorkshire.

Methods A questionnaire was circulated to 141 randomly selected general dental practitioners in the South Yorkshire area between January 2012 and January 2013.

Results The response rate was 79% (112/141). Five of the returned questionnaires were incomplete and therefore not usable. Seventy-nine percent of respondents were general dental practitioners (GDPs) working in mainly NHS or mixed practices. The year of graduation varied between 1970 and 2011. Forty-one percent (44/107) stated that they had never left a tooth on open drainage. Twenty-nine percent (31/107) stated that they sometimes leave teeth on open drainage. Of those respondents who currently leave teeth on open drainage, most (68%) would leave teeth on open drainage for one to two days or less.

Conclusions This survey revealed that the practice of leaving teeth on open drainage is still present in general dental practice. Current guidelines do not comment on the use of this treatment modality. There is a need to ascertain further information about practices throughout the United Kingdom in order to provide clear evidence-based guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dental pulp is encased within a solid mineral structure. Any change in the pulp can lead to an increase in pressure within the pulp chamber and root canal system. Infection of the canal system leads to inflammation of the pulpal tissue, involving a complex interaction of inflammatory mediators released during pulpal injury.1 Neuropeptides (including substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide) and other mediators such as bradykinin and histamine are involved in the inflammatory process, resulting in a number of consequences. These include neural proliferation, vascular proliferation and increased vascular permeability.2,3 An increase in blood flow to the pulp excites both A-delta fibres and C fibres and inflammatory mediators lower the sensory nerve threshold.4 Continuation of the inflammatory process leads to micro-abscess formation, ultimately leading to pulpal necrosis.5 Necrosis can occur painfully or silently.6 Following pulpal necrosis it has been hypothesised that the production of gases by the invading bacteria can lead to an increase in pressure within the pulp space that leads to pain (often exacerbated by hot and relieved by cold application).4,7,8

Pulpal necrosis may progress to the development of acute periradicular periodontitis (inflammation of the periodontal ligament without obvious apical pathology detectable on radiographs), an acute apical abscess (presence of pus) or chronic periradicular periodontitis (often asymptomatic with the presence of a radiolucency seen on a radiograph) or chronic apical abscess (presence of pus draining from a sinus). Patients usually seek dental treatment as a result of excruciating pain due to painful necrosis of the pulp, acute periradicular periodontitis or acute apical abscess.8

In the presence of pain, as a result of pressure building up within the pulp space, accessing the pulp chamber relieves the majority of the symptoms. The tooth can then either be closed with a dressing in situ or left open to drain (open drainage).

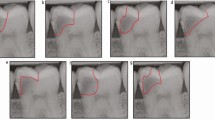

The concept of leaving teeth on open drainage has been discussed since the 1970s (Fig. 1). Initially it was advocated that teeth with an acute apical abscess should be left open to drain, to alleviate the pressure caused by inflammation and allow drainage of pus. At that time it was thought that the symptoms would return when the tooth was dressed and closed following endodontic preparation and therefore Weine9 described leaving teeth on open drainage for three to seven days following emergency appointments. A culture of the purulent discharge was taken at the time of access. At the second appointment the tooth was prepared to within one size of the estimated final width, preferably under rubber dam, using sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) 5.25% as an irrigant, and left to drain for a further two to five days. Antibiotic administration was not suggested, as drainage of the tooth was accomplished. At the third appointment the tooth was not prepared further but irrigated with 3% hydrogen peroxide and 5.25% NaOCl and dressed. During the next visit canal preparation was completed and the tooth was dressed again, with a fifth appointment necessary for obturation.9 Weine stated the following 'if you file, don't close. If you close don't file'.9

Weine et al. also published a study of 81 teeth that were referred for endodontic treatment following the access cavity being left open and 144 teeth referred following emergency appointments where the access cavities were dressed (all teeth were thought to be vital at the time of access during the emergency appointment).10 Leaving a tooth open was advocated when there was insufficient time during the emergency appointment to access, allow for drainage, wash and dry the canal. On average 5.11 appointments were needed per case for the completion of the endodontic treatment for those teeth left on open drainage and 3.31 appointments for those that were closed, with more unscheduled appointments for relief of recurrent exacerbations being necessary in the group where the teeth were left on open drainage. There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of number of appointments needed to complete treatment and inter appointment exacerbations.10 Outcomes of endodontics were not assessed as only half the patients in each group returned for reassessment at two years, however, it was suggested that vital teeth be kept closed to minimise complications.

D S August disagreed with this method of treatment and reported on 271 teeth that were instrumented and dressed (closed) following a period of open drainage.11 One hundred and thirteen teeth were associated with radiolucent areas and 158 without radiolucent areas before treatment. The treatment protocol included preparation, irrigation with 2.5% NaOCl, medication and temporary closure, followed by the same procedure again 24 hours later. At 18 months or more, an overall success rate (no clinical or radiographic signs of infection) of 96.7% for teeth previously left on open drainage was reported. However, teeth that needed surgical endodontics were not considered failures with the healing rate reducing to 93.7% if these teeth were considered failures. August concluded that it was safe to file (that is, prepare) the canal and close at the same appointment.11

In a retrospective analysis of 5,000 cases published in 1980, it was found that 518 (10.4%) were left open for drainage.12 Adjunctive treatment to open drainage included incision and drainage, incision and drainage followed by apicectomy, antibiotics or antibiotics and apicectomy in order to achieve patient comfort. It was unclear why some teeth were left open and some closed. The teeth were prepared and irrigated with NaOCl and left on open drainage for one week and if the tooth remained symptomatic the tooth would be reopened. Eighty-two percent of these teeth were successfully closed after one to four attempts. Of teeth left on open drainage, 17.8% needed surgical treatment as symptoms persisted after the fourth attempt at closing. The longer the tooth was left opened, the higher the number of attempts before a closed tooth remained asymptomatic.12

In 1982, August refuted the need for numerous dressings using findings from his practice (311 teeth, 173 with associated radiolucent areas and 138 without).13 He reported that following a period of open drainage it was possible to prepare the canal, irrigate and temporise with an inter-appointment medicament in 95% (n = 295) of cases without complications. However, it was noted that 19 of these patients required supplemental treatment such as incision and drainage, medication, occlusal adjustment, dressing change and surgical endodontics. Now consistent with current knowledge, August in 197711 and 1982,13 reported that teeth with periapical radiolucent areas caused more problems.

During the 1980s and 1990s there appeared to be a change in thinking, away from keeping teeth on open drainage. In 1994 it was reported that leaving teeth open can lead to periapical epithelial proliferation, by testing for the presence of secretory IgA in the periapical tissues. It was suggested that this may result in a 'more cystic formation'.14 In a retrospective study in Finland of 601 non-vital teeth (resulting from carious exposure) treated by dental students, 103 teeth were left on open drainage for one to two weeks (due to excessive periapical exudate with no indication for incision); 94 teeth had other emergency treatment and 404 teeth were endodontically treated without prior emergency treatment. Out of all of the teeth, 8.9% had 'flare-ups' (symptoms noted by the patient). Leaving a tooth on open drainage showed increased amounts of bacteria and inflammatory cells identified by Gram staining methods. Overall success rates were 72.2% to 78.9% and the complication rates were similar for all the groups.15

It can be concluded that open drainage is not required for higher success rates and may be associated with increased bacterial counts and more treatment appointments. Recommendations in endodontics have moved on from this practice and it is known that the presence of microorganisms is required for the development of an abscess associated with a tooth. Kakehashi showed that apical periodontitis would not develop in germ free rats.16 Sundqvist showed that apical periodontitis with apical bone resorption occurs only if the necrotic pulp becomes infected.17 Moller showed that bacteria from the root canals of teeth with apical periodontitis would cause apical periodontitis if inoculated into the root canals of other teeth.18 Some have shown the presence of microbes such as Enterococcus faecalis (a gastrointestinal bacterium that is rarely found in infected but untreated root canals) and pulses/vegetable matter in the periapical tissue (the latter thought to lead to pulse granulomas) with these findings being attributable to the opening of the root canal system to the oral cavity.19,20,21 As a result, leaving teeth on open drainage is less accepted and there has been a trend towards single visit endodontics, with good outcomes.22,23

This questionnaire-based evaluation gathered information regarding the current practice of GDPs in South Yorkshire, in relation to leaving teeth on open drainage. The aim of this survey was to identify the following:

-

Is open drainage currently practised?

-

If so, under what circumstances?

-

How are teeth that are left on open drainage definitively managed?

-

What are GDPs attitudes to leaving teeth on open drainage?

The objective of this evaluation is to improve the care provided to patients by improving knowledge of the current literature available in relation to leaving teeth on open drainage.

Method

This questionnaire-based evaluation was undertaken in primary dental care practices in the South Yorkshire area. A questionnaire was developed, based around the aims of this evaluation (Fig. 2). The questionnaire was piloted on ten primary care practitioners working at Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (STHNFT). The questionnaire underwent minor changes as a result of piloting. Approval from the Clinical Effectiveness Unit at STHNFT was sought and granted. A list of practitioners on the General Dental Council register with a general practice address in South Yorkshire was compiled on an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft® Excel® for Mac 2011). One hundred and forty-one GDPs were selected using computer-generated randomisation (30% of the 471 practitioners identified from the GDC register).

The questionnaire was initially sent with a covering letter explaining the nature of the evaluation to the 141 GDPs in January 2012, with self-addressed return envelopes. The questionnaires were numbered and the database of GDPs was maintained for the sole purpose of establishing which questionnaires were returned, so that reminders could be sent to non-responders. Sixty-nine questionnaires were returned. A repeat questionnaire with a covering letter was sent to 72 non-responding dentists in December 2012. A member of staff collated the data from the completed questionnaires without access to the original database and therefore all results were anonymised. The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis.

Results

The initial questionnaire was circulated in January 2012 to 141 GDPs and the response rate was 49% (69/141). The response rate to the second circulation of the questionnaire was 59% (43/72). The overall response rate was 79% (112/141). Five of the returned questionnaires were incomplete and therefore not usable. Analysis was carried out using the 107 usable questionnaires.

The majority (79%) of respondents were GDPs working in mainly NHS or mixed practices (Tables 1 and 2). The mixed practices varied from 40% NHS and 60% private to 99% NHS and 1% private practice. The year of graduation varied between 1970 and 2011 (Table 3).

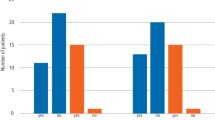

Most of the respondents stated that they would treat an acute apical abscess by opening and dressing the tooth or with antibiotics (the question asked respondents to indicate all those responses that apply). Some advocated open drainage as an acceptable treatment modality for an acute apical abscess (Fig. 3). Of the 107 usable questionnaires, 44 (41%) stated that respondents had never left a tooth on open drainage. Thirty of the 107 respondents (29%) stated that they would leave teeth on open drainage (Fig. 4). One stated 'yes and no' for the question regarding currently leaving teeth on open drainage and therefore this has been included as currently leaving teeth on open drainage. For those that did leave teeth on open drainage in the past, the majority of respondents had qualified between 1978 and 1982. Those that would currently leave teeth on open drainage show no clear majority for any year of qualification (Fig. 5).

The main reason cited for leaving teeth on open drainage was 'excessive periapical exudate' and 'non vital tooth with spreading facial swelling' or a 'non-vital tooth with a fluctuant swelling'. 'Other' reasons included 'when no other treatment has worked, that is, 'cannot incise or numb'. Of those respondents who currently leave teeth on open drainage, most would do so for one to two days or less (68%). Some would leave teeth on open drainage for one to two weeks (29%). The 'other' time period stated was 'if root canal treatment (RCT) for one to two days and if extraction at any time' (Fig. 6). Additional treatment provided at the time of instigating open drainage included instrumentation/irrigation of the canal, antibiotics, extirpation and/or analgesia and 'dressed and sealed'. Following a period of open drainage a variety of treatment was provided including non-surgical endodontic treatment, extraction, referral to specialist, and surgical endodontics (Fig. 7).

In the comments section of the questionnaire, several respondents stated that leaving teeth on 'open drainage' was 'inappropriate treatment' and that they were 'not aware of any circumstances when it is best to leave a tooth on open drainage'. Some would like to know more about the guidelines regarding open drainage, as they were 'not really given proper guidance on this!' Others stated that 'leaving a tooth on open drainage in fact poses more risk of retrograde infection' and 'it would allow ingress of pathogenic oral bacteria into the root canal system, which can prove exceedingly difficult to then treat'. A few would only consider leaving a tooth open to drain if extraction of the tooth was planned. Some stated that they were not taught open drainage as 'a suitable method of treatment'.

Those who provide open drainage currently advocated its use only when 'severe swelling is present', 'excessive pus accumulation', 'when patient re-attends with continual severe pain following previous visits when initial non-surgical endodontic treatment has been started and produced no response or large diffuse facial swelling (extra oral)' and 'excessive pus/exudate and patient in pain'. One respondent stated that open drainage 'allows stabilisation and correct assessment of healing response. Followed by delicate instrumentation and medicaments – with root obturation as soon as possible after stabilisation that is, one week maximum – good results'.

Discussion

The response rate of 79% is good as it is above the reported mean response rates (57.5%) of healthcare professionals to postal surveys.24 There is likely to be some non-response error as the non-responders may be of different characteristics to those who did respond.25 The demographic data of this service evaluation indicates that responses were received from a variety of practitioners working mainly in general dental practice that is wholly NHS or mixed NHS and private practice. The respondents had been qualified for a wide range of time periods.

This questionnaire-based study revealed that leaving teeth on open drainage is still current practice for 29% of practitioners surveyed. The consequences of leaving teeth on open drainage include heavy colonisation by microorganisms and the accumulation of food debris within and beyond the canal system.15,16 Infected teeth are treated on a microbiological basis, with the aim of eliminating intraradicular infection being the key to successful treatment.26,27 There may be issues of changing the microflora within the canal system with open drainage techniques. Theoretically there may be more oxygen in a tooth left open and therefore fewer anaerobic bacteria, which may be easier to eliminate, however, there may be introduction of bacteria such as E. faecalis, which are more difficult to eliminate.28

Current practice is moving towards access, establishing working length, preparing and irrigating canals within the first visit and in most cases, where possible, to complete the endodontic treatment with a number of studies having shown single visit endodontics to be successful.22,23

Endodontic treatment has high success rates when carried out under rubber dam, using NaOCl as an irrigant (supplemented by ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid [EDTA] as penultimate wash in retreatment cases), using apex locators to establish working length and maintaining patency.29 Success rates have been shown to be affected by the presence and size of preoperative apical areas, presence of preoperative sinus or root perforation, patency, length of root filling (short better than long), the use of chlorhexidine (negative impact), the use of EDTA (positive impact on re-treatment cases), inter appointment flare ups and a good quality coronal seal.29

The use of antibiotics in the management of acute pain due to pulpal or periradicular causes is not recommended. The use of these should be limited to those patients who may suffer from systemic effects as a result of dental infection.30

The current quality guidelines for non-surgical endodontics do not include open drainage as a treatment modality and the aim of treatment is stated as 'either to maintain asepsis of the root canal system or to disinfect it adequately'.31

Conclusion

This evaluation revealed that the practice of leaving teeth on open drainage is still present in general dental practice especially for situations when patients present with severe swelling and pain. Current guidelines do not advocate the use of this treatment modality. The recommendation is to avoid practices that introduce microorganisms into root canal systems. The available evidence does not show benefit from the practice of open drainage. There is a need to ascertain further information about practices throughout the UK (in primary and secondary care settings) in order to provide clear evidence-based guidelines.

References

Caviedes-Bucheli J, Munoz H R, Azuero-Holguin M M, Ulate E . Neuropeptides in the dental pulp: the silent protagonists. J Endod 2008; 34: 773–788.

Rodd H D, Boissonade F M . Innervation of the human tooth pulp in relation to caries and dentition type. J Dent Res 2001; 80: 389–393.

Rodd H D, Boissonade F M . Vascular status in human primary and permanent teeth in health and disease. Eur J Oral Sci 2005; 113: 128–134.

Yu C, Abbott P V . An overview of the dental pulp: its functions and responses to injury. Aust Dent J 2007; 52: S4–S16.

Rodd H D, Boissonade F M . Immunocytochemical investigation of immune cells within human primary and permanent tooth pulp. Int J Paediatr Dent 2006; 16: 2–9.

Michaelson P L, Holland G R . Is pulpitis painful? Int Endod J 2002; 35: 829–832.

Cohen S, Hargreaves K M . Pathways of the pulp. 9th ed. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier, 2006.

Abbott P V, Yu C . A clinical classification of the status of the pulp and the root canal system. Aust Dent J 2007; 52: S17–S31.

Weine F S . Closing a toothleft open for drainage. Chronicle 1975; 38(8): 406–407, 410.

Weine F S, Healey H J, Theiss E P . Endodontic emergency dilemma: leave tooth open or keep it closed? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1975; 40: 531–536.

August D S . Managing the abscessed tooth: instrument and close? J Endod 1977; 3: 316–319.

Bence R, Meyers R D, Knoff R V . Evaluation of 5,000 endodontic treatments: incidence of the opened tooth. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1980; 49: 82–84.

August D S . Managing the abscessed tooth: instrument and close? – Part 2. J Endod 1982; 8: 364–366.

Torres J O, Torabinerjad M, Matiz R A, Mantilla E G . Presence of secretory IgA in human periapical lesions. J Endod 1994; 20: 87–89.

Tjaderhane L S, Pajari U H, Ahola R H, Backman T K, Hietala E L, Larmas M A . Leaving the pulp chamber open for drainage has no effect on the complications of root canal therapy. Int Endod J 1995; 28: 82–85.

Kakehashi S, Stanley H R, Fitzgerald R J . The effects of surgical exposures of dental pulps in germ-free and conventional laboratory rats. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1965; 20: 340–349.

Sundqvist G . Bacteriological studies of necrotic dental pulps. Umea University Odontological Dissertations: No 7, 1976.

Moller A J . Microbiological examination of root canals and periapical tissues of human teeth. Methodological studies (thesis). Odontol Tidskr 1966; 74: 1–380.

Portenier I, Waltimo T M, Haapasalo M . Enterococcus faecalis – the root canal survivor and 'star' in post-treatment disease. Endodontic Topics 2003; 6: 135–159.

Simon J H, Chimenti Z, Mintz G . Clinical significance of the pulse granuloma. J Endod 1982; 8: 116–119.

Nair P N . On the causes of persistent apical periodontitis: a review. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 249–281.

Figini L, Lodi G, Gorni F, Gagliani M . Single vs multiple visits for endodontic treatment on permanent teeth. Cochrane DB Syst Rev 2007; 17: CD005296.

Paredes-Vieyra J, Enriquez F J . Success rate of single vs two-visit root canal treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis: a randomised controlled trial. J Endod 2012; 38: 1164–1169.

Cook J V, Dickinson H O, Eccles M P . Response rates in postal surveys of healthcare professionals between 1996 and 2005: An observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 2009; 9: 160.

Dillman D A, Smyth J D, Christian L M . Internet, mail and mixed-mode surveys: the tailored design method. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, 2009.

Sjogren U, Figdor D, Persson S, Sundqvist G . Influence of infection at the time of root canal filling on the outcome of endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis. Int Endod J 1997; 30: 297–306.

Sundqvist G, Figdor D, Persson S, Sjogren U . Microbiologic analysis of teeth with failed endodontic treatment and the outcome of conservative re-treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1998; 85: 86–93.

Sundqvist G, Figdor D . Life as an endodontic pathogen. Endodontic Topics 2003; 6: 3–28.

Ng Y-L, Mann V, Gulabivala K . A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of non-surgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J 2011; 44: 583–609.

Longman L P, Preston A J, Martin M V, Wilson N H . Review. Endodontics in the adult patient: the role of antibiotics. J Dent 2000; 28: 539–548.

European Society of Endodontology. Quality guidelines for endodontic treatment: consensus report of the European Society of Endodontology. Int Endod J 2006; 39: 921–930.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Derek Hall, Adnan Safdar and Muhammed Jasat for helping with the early stages of this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eliyas, S., Barber, M. & Harris, I. Do general dental practitioners leave teeth on 'open drainage'?. Br Dent J 215, 611–616 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1192

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.1192