Key Points

-

Informs readers of the proportion of respondents who may not attend the dentist due to anxiety.

-

Combined with previous papers this series gives an estimated need for a sedation service of 6.9% throughout the entire adult population, based on both attendees and non-attendees.

-

This could allow service commissioners to determine levels of sedation provision based on need rather than demand.

Abstract

Background This is the third paper in a series of four examining a tool which could be used to determine sedation need among patients.

Aim The aim of this paper was to assess the reasons why people do not attend the dentist regularly, in order to understand the potential need for sedation services among both attending and non-attending patients.

Methods and results A large telephone survey conducted across 12 primary care trusts (PCTs) found that 17% of participants did not attend the dentist regularly. One of the top reasons given for non-attendance that could be considered a barrier was fear/anxiety. The figure reached in paper 2 (Br Dent J 2011; 211: E11) stated that approximately 5% of attending patients will, at some time, need sedation services. However, the data from this survey have suggested that anxiety accounts for 16% of people who do not attend the dentist regularly.

Conclusion It could be assumed that if non-attending patients were included, with high levels of anxiety, the sedation need would rise to 6.9% throughout the entire population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There have been numerous studies which have indicated that fear of dental treatment and oral surgery is a significant problem for a large proportion of the population.1,2 However, many studies have concentrated on student populations3 or dental practice patients.4 These are not always representative and in some instances only include attending patients, missing out a section of the population who may not attend due to high levels of anxiety.

Dental anxiety is thought to be a barrier in seeking dental treatment.1,5 In a Gallup Poll survey 22% of people surveyed suffered anxiety levels that were so high they had delayed seeking dental treatment.2 This could be an important factor as dental attendance has been shown to have clear association with dental health.6 Another survey indicated those who attend only when they have some trouble with their teeth had, on average, one less tooth than those who attend for regular check ups.7 Other studies have also indicated that measures used to control dental anxiety may help improve the status of oral health within the older adult population.8

The 1998 Adult Dental Health Survey carried out under the auspices of the Office of National Statistics, Universities of Birmingham, Dundee, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Wales involved 6,204 interviews conducted across the UK. The survey indicated that 59% of dentate adults in the UK attend the dentist regularly; this had risen from 43% in the 1978 survey.7 The study also showed fear and anxiety were clearly still a problem for adults with approximately a third of those interviewed stating they always feel anxious about going to the dentist. There was not a drastic difference when looking at anxiety between 'regular attendees' (43%) and those who only attend when they have some trouble with their teeth (46%). However, these data did not connect anxiety towards attendance, the results merely indicated feelings towards visiting the dentist rather than reasons given for not attending. Therefore while the data gives a good impression of the levels of anxiety regarding dental visits they cannot be used to determine whether anxiety, or any other reason, is a significant barrier to seeking dental treatment.

This paper is the third instalment of a set of articles examining the health needs surrounding dental sedation and the role anxiety plays within obtaining dental treatment. The first two papers explored a tool (IOSN) that could be used to assess the need for sedation in relation to anxiety, medical indicators and treatment complexity. These articles indicated that approximately 5% of people who attend the dentist would, at some time, require sedation due to the combination of these three factors. However, it was noted that as the research was conducted on those who attend the dentist it failed to incorporate those who do not attend, possibly due to high levels of anxiety. It therefore may not give a completely accurate view of those who have high levels of anxiety in relation to their dental care and may require sedation in order to complete various dental examinations and treatments. In order to address this, data have been taken from a survey conducted across 12 PCTs in England relating to dental access and attendance.

The purpose of the current study was to gain an understanding of the reasons why people do not attend the dentist and relate this to its impact on a sedation tool created to determine sedation need among dental patients.

Methods and materials

The data obtained in this study were gathered from a large telephone survey conducted across 12 PCTs in England. The PCTs were selected to include some that were known to have good dental access and some which had poor dental access. The survey used a random sampling design and was conducted over three weeks in September 2009. It aimed to achieve 1,000 interviews in each PCT.

The population for the survey included adults aged 16 and over. Within each PCT, the sample was required to be representative of the adult population of that particular PCT. Although telephone surveys have certain limitations, namely that participants require a landline and may not be available to answer the phone when the survey is conducted, it is the most appropriate method for such a study which requires the ability to contact both attendees and non-attendees of dentists on a large scale. To ensure a representative sample was contacted the List-assisted RDD approach along with random sampling was used. After establishing if the household contacted was within the correct area, a computerised method of random selection was employed to choose the individual to be interviewed within that household.

In total 12,002 interviews were conducted and successfully completed with an overall response rate for this survey of 32%. The data were weighted at the end of the survey before analysis to make them comparable with the general population within each PCT – this was achieved by weighting the data for each PCT to the profile of that PCT by age within gender. For each PCT, non-response weights were calculated for four age categories (16-29, 30-44, 45-59, 60+) within gender.

Statistical analyses of the data utilised descriptives and comparisons between groups using tests such as Chi square and Mann Whitney U.

Results

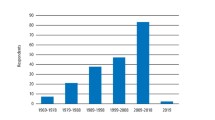

All 12 PCTs had approximately 1,000 respondents each, to be used within the analysis. The distribution of those who attend regularly (attended the dentist in the last two years) to those who do not attend (last visit to the dentist over two years ago) can be seen in Figure 1. On average, throughout all 12 PCTs included, 17% of respondents indicated they do not attend the dentist regularly, ranging from 14%-24% over the PCTs.

The demographics of the respondents' are shown in Table 1 split by regular and non-regular attendees. Analysis using Chi square demonstrates significant difference in the deprivation indicators between regular and non-regular attendees overall, although not throughout the majority of the PCTs when analysed individually. Throughout the majority of the PCTs non-attendees appeared to be on average slightly older. However, it should be noted 13% of non-attendees were made up of people aged over 75 and over half of these respondents (57%) did not have any natural teeth left and may therefore have been advised to attend the dentist only every two years. Results from paper 4 within this series of articles also showed less than 1% of those receiving sedation were over 75-years-old. This is an interesting finding given this group of patients may present with complex treatment needs and medical conditions which indicate that treatment under sedation may be beneficial. Removing those who no longer had natural teeth from the dataset revealed those who attend regularly are on average slightly older than those who do not (Table 1). Gender also shows a significant difference, with males less likely to attend the dentist regularly than females (χ2 (1) = 49.479, p <0.001).

Table 2 demonstrates the distribution of how the respondents' dental care is delivered across regular and non-regular attendees. There was a significant difference for eight of the 12 PCTs between the type of attendees and delivery of treatment, with regular attenders more likely to use private dentists (36.0%) than non-regular attenders (29.7%) (χ2 (2) = 30.545, p <0.001).

Tables 3, 4 and 5 reveal the reasons respondents have given for not attending the dentist in over two years. The top two main reasons given (Table 3) were 'having had no need to/no problems with teeth' (29%) and 'no longer having any natural teeth' (16%). As these do not constitute barriers to dental treatment they have been disregarded as, while interesting, they are not relevant for the purpose of this study. The top reason given for non-attendance that could be considered a barrier was 'Don't like dentists/Scared of dentists/Have had a bad experience at the dentist', all of which will be further described as 'anxiety'. Anxiety was given as a main reason for five out of the 12 PCTs. If it was not stated as a 'top' main reason it was the highest scoring secondary reason for not attending the dentist for the majority of the PCTs. Surprisingly there is a large variation between the levels of anxiety throughout the PCTs analysed. The highest level is 23% with the lowest at 9% when looking at main and secondary reasons combined.

For those who stated anxiety as a secondary reason: 35% said they didn't have any problem with their teeth, 12% stated the cost of NHS dental treatment and 11% said they 'hadn't got round to it/been too busy' as their main reason for not attending.

When assessing anxiety by gender there was a statistically significant difference seen (χ2 (1) = 14.696, p <0.001), with females 1.5 times more likely to be anxious about the dentist (Table 5). Again deprivation (p >0.05) showed no statistical significance in relation to anxiety as a reason for non-attendance. Age did show a difference when looking at anxiety but only for females. Females who suffered from anxiety in relation to their dental care were on average slightly older (Mdn = 52-years-old) compared to those who did not state anxiety as a reason (Mdn = 48-years-old) U = 41840, z = -3.325, p <0.01.

Discussion

Fear and anxiety are one of the more usual reactions when the topic of dentists or visits to the dentist is mentioned.7 However, it is unclear the exact impact this has upon non-attendance as many studies involve unrepresentative samples,2,3 or do not specifically relate 'anxiety' to attendance.7 This study has specifically looked at indicators of non-attendance (have not visited the dentist in over two years) across a large population of 12 PCTs. Throughout the PCTs there was an even distribution across gender and age, due to the weighting of the data. This was to gain a representative sample in order to generalise to the wider population. The average percentage of respondents who did not regularly attend the dentist was 17%. This differs from the common belief that around two thirds of people do not attend the dentist. Although it is more in line with the change seen in the Adult Dental Health Survey over the years which in 1978 indicated 57% of people did not attend the dentist regularly, this figure dropped to 41% in 1998.7,9 The most recent data from the Adult Dental Health Survey (2009) have shown that 82% of dentate adults said their last visit to the dentist was in the previous two years,10 giving a similar percent–age seen in this study, with 83% also having their last visit within two years.

It is clear there is a significant difference between attendance for males and females, with males less likely to attend the dentist regularly. This corresponds to a similarly large scale study which indicated men of all ages were less likely to go for dental check-ups than women.7

An average of 16% of participants indicated anxiety was either a main or secondary reason for not regularly attending the dentist. This corresponds well to similar large scale studies which found high dental anxiety in 12% of respondents questioned.11 The top two responses given for non-attendance did not necessarily relate to barriers in obtaining dental treatment ie 'no longer had any natural teeth' or they 'had no problem with their teeth'. Instead, these reasons could be attributed to a lack of understanding as to the frequency that people should be attending the dentist. Anxiety was therefore examined with the removal of these participants, which showed an average of 24% of participants stated anxiety was a reason for not regularly attending the dentist when specifically looking at barriers to dental treatment.

It should be noted there was a wide variation between PCTs in the levels of anxiety expressed by people, in relation to why they have not attended the dentist in the last two years, ranging from 9% to 23%. One theory for this variation could be due to the availability of sedation services within the area. Further research should be carried out to determine if this is the case.

Deprivation did not have a significant effect on whether people were anxious or not in relation to attending the dentist. This corresponds to paper 2 which found that the practice attended and deprivation had no significant effect on need for sedation (partly determined by anxiety). However, it is evident there is a difference in gender when looking at anxiety as a reason given for non-attendance; women were 1.5 times more likely to report anxiety as a reason for not attending than men. This also corresponds to previous studies where it has been stated that females were 2.5 times more likely to report themselves as having a high level of dental fear12 as well as relating to paper 2 discussed earlier, where females were 4.7 times more likely to be anxious in relation to their dental treatment.

Conclusion

This paper is the third in a series of four that consider the complex health needs surrounding dental sedation. The previous two papers examined a tool which could be used to determine sedation need among attending patients. The figure reached in these previous papers stated that approximately 5% of patients will, at some time, need sedation services. However, given the data from this survey it could be assumed that, given the split of attendees to non-attendees and the level of sedation required in attending patients, if non-attending patients were included with high levels of anxiety, the sedation need would rise to 6.9% throughout the entire population. The proportion of non-regular attendees with possible need for sedation due to anxiety determined using data from all PCTs included in this survey (16% of 17% = 0.0272) combined with regular attendees' need for sedation established from paper 2 (5% of 83% = 0.0415) would equal 0.0687 or 6.9%.

References

Flick W G, Clayhold S . Who should determine the medical necessity of dental sedation and general anesthesia? A clinical commentary supported by Illinois patient and practitioner surveys. Anesth Prog 1998; 45: 57–61.

Delfino J . Public attitudes toward oral surgery: results of a Gallup poll. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1997; 55: 564–567.

Teo C S, Foong W, Lui H H, Vignehsa H, Elliott J, Milgrom P . Prevalence of dental fear in young adult Singaporeans. Int Dent J 1990; 40: 37–42.

Stabholz A, Peretz B . Dental anxiety among patients prior to different dental treatments. Int Dent J 1999; 49: 90–94.

Woolgrove J, Cumberbatch G . Dental anxiety and regularity of dental attendance. J Dent 1986; 14: 209–213.

McGrath C, Bedi R . The association between dental anxiety and oral health-related quality of life in Britain. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004; 32: 67–72.

Nuttall N M, Bradnock G, White D, Morris J, Nunn J . Dental attendance in 1998 and implications for the future. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 177–182.

Elter J R, Strauss R P, Beck J D . Assessing dental anxiety, dental care use and oral status in older adults. J Am Dent Assoc 1997; 128: 591–597.

Nuttall N M, Davies J A . The frequency of dental attendance of Scottish dentate adults between 1978 and 1988. Br Dent J 1991; 171: 161–165.

Chenery V . Adult dental health survey 2009 – England key findings. London: The Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2011. Available at: http://www.ic.nhs.uk/webfiles/publications/007_Primary_Care/Dentistry/dentalsurvey09/AdultDentalHealthSurvey_2009_England_KeyFindings.pdf

Humphris G M, Dyer T A, Robinson P G . The modified dental anxiety scale: UK general public population norms in 2008 with further psychometrics and effects of age. BMC Oral Health 2009; 9: 20.

Chanpong B, Haas D A, Locker D . Need and demand for sedation or general anesthesia in dentistry: a national survey of the Canadian population. Anesth Prog 2005; 52: 3–11.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to Mike Warburton and Helen Miscampbell who provided access to the data and advice on the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goodwin, M., Pretty, I. Estimating the need for dental sedation. 3. Analysis of factors contributing to non-attendance for dental treatment in the general population, across 12 English primary care trusts. Br Dent J 211, 599–603 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.1053

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.1053

This article is cited by

-

A review of the indicator of sedation need (IOSN): what is it and how can it be improved?

British Dental Journal (2018)

-

Conscious sedation: is this provision equitable? Analysis of sedation services provided within primary dental care in England, 2012–2014

BDJ Open (2016)

-

Assessing sedation need and managing referred dentally anxious patients: is there a role for the Index of Sedation Need?

British Dental Journal (2015)

-

Safety and predictability of conscious sedation in dentistry – a multi-centre regional audit: South and West Wales experience

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

Estimating the need for dental sedation: evaluating the threshold of the IOSN tool in an adult population

British Dental Journal (2013)