Key Points

-

Following the new contract, the Department of Health promoted 'new ways of working' for GDPs to improve oral health through oral health promotion.

-

Undergraduate and FD1 training have not clarified the difference between oral health education and oral health promotion in terms of 'role' in general dental practice.

-

Further training is required if oral health-promoting 'new ways of working' are to become a reality.

Abstract

Objective To explore the perceptions of first year foundation dentists (FD1s) regarding oral health education (OHE) and its role in general dental practice.

Design Focus group discussions.

Setting Postgraduate training venues and general dental practices utilised for foundation training in South Wales, UK.

Subjects (materials) and methods Nineteen FD1s accepted an invitation to take part in a series of focus groups. Focus groups were transcribed and data analysed using a constructive process of thematic content analysis to identify themes and theories relating to the FD1s' understanding of OHE and its role in the delivery of care as general dental practitioners.

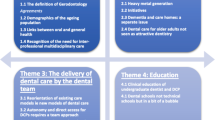

Results The data fell into three broad categories: the teaching of OHE delivery at undergraduate level; factors influencing the 'frequency and content' of OHE delivery; and barriers to 'effective and successful' OHE. The first category identified perceptions of the 'gold standard' of OHE following undergraduate experiences. The practicalities of the acquisition of technical skills had created a simplistic compartmentalised view of OHE which was not a priority in adult dental care. The second category covered triggers for delivering OHE; in general these were reactive rather than preventive. The last category dealt with successful OHE; unsuccessful OHE was attributed to the patient although communication barriers were recognised.

Conclusion The subtle but important difference between OHE and oral health promotion (OHP) in terms of its role in general dental practice is recognised theoretically but not as a reality in practice. OHE is often compartmentalised and a simplistic approach to its delivery is taken. Against a backdrop of commissioning to improve health this has implications in developing organisational processes within general dental practice and training in order to achieve this.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The establishment and maintenance of a disease inactive oral environment will be largely dependent on the individual patient's health behaviours.1 The role of the general dental practitioner in guiding these behaviours has been increasingly emphasised both at undergraduate and postgraduate level.2,3 The recently published Steele Report specifically refers to the responsibility the general dental practitioner (GDP) has in educating patients in health behaviours that will enable them to sustain oral health throughout life.4 The delivery of effective prevention is a key element of the delivery of general dental services, particularly in the context of the recent reviews of the new NHS dental contract.4,5

Stillman-Lowe reports the definition of OHE as 'any learning activity which aims to improve individuals' knowledge, attitudes and skills relevant to their oral health'.6 OHE contrasts with oral health promotion (OHP), which she describes as 'any process which enables individuals or communities to increase control over the determinants of their oral health'.6 The traditional definition of health promotion comprises health education, prevention and health protection.7 Health protection is the remit of legislation for which individual general practitioners have no responsibility. Legislative changes resulted in the new contract of 2006. It could be argued that the Department of Health puts OHP as the cornerstone of its strategy for improving oral health, with GDPs as oral health promoters described as 'new ways of working'.8

Since 2006, Primary Care Organisations (PCOs) have been additional stakeholders in the planning of dental services.9 According to the Department of Health, PCOs will want to channel services towards those that practise 'new ways of working' with effective OHE/prevention as part of their armamentarium, as there are both clinical and financial motives to promote services that improve community oral health.8

Stillman-Lowe identified limitations in the delivery of OHE in primary dental care as it has been practised in the UK and observed that very little had been achieved over the past decade in improving the delivery of OHE.6

As recently qualified dentists embark on their careers as dental professionals they are in the process of becoming professionally socialised in general dental practice. Understanding how the role and delivery of OHE is perceived will provide an insight into their realities. This is particularly pertinent at a time of change when PCOs commission services. The future workforce will need to embrace 'new ways of working' which will include OHE and prevention as integral components of service delivery in order to satisfy an OHP approach to General Dental Practice and services.

This paper explores the perceptions of first year foundation dentists (FD1s) regarding OHE and its role in primary dental care. Establishing some baseline viewpoints will identify potential problem areas that can be addressed by educationalists within the profession in order to prepare the future workforce.

Methodology

Design

Due to the lack of relevant research in this area and the need for a detailed understanding of participant's perspectives of the topic, a qualitative research approach was used.10 Qualitative methods, such as focus groups, can offer a unique insight into people's personal perspectives, providing a more comprehensive understanding of their beliefs, knowledge and attitudes as well as offering greater depth and methodological flexibility than quantitative research methods such as structured questionnaires.11,12

Recruitment and sampling

The research was conducted in South Wales, UK. A REC-approved letter of invitation, participant information sheet and consent form, were sent to all FD1s in three of the South Wales training schemes. Those interested in participating signed the consent form and returned them to the researcher (RH) in a freepost envelope. In total 19 respondents participated in the study (eight males and 11 females). Fifteen were graduates of Cardiff University Dental School, two were graduates of Guy's, King's and St Thomas' dental school, London, one graduated in Liverpool and one in Iraq. At the time of the participation in the focus groups all FD1s had been in general dental practice for five to six months.

Data collection

Data were collected through focus groups. Focus groups are used for generating information on collective views, and the meanings that lie behind those views.13 They are also useful in generating a rich understanding of participants' experiences and beliefs.14 Four separate focus groups were conducted (size of focus groups ranged from three to six participants, plus the moderator – RH). A semi-structured interview schedule was devised to explore issues relating to perceptions and experience of the delivery of OHE in general dental practice. Interview questions informed the discussions and areas explored in the interview schedule. These included opinions about the teaching of OHE skills at undergraduate level, methods used in the delivery of OHE and perceived success and limitations of OHE delivery.

Focus groups were conducted in a quiet, private area in one of two hospitals where the FD1 groups routinely met for training sessions. All focus group discussions were moderated by the main researcher (RH). Interviews were conducted between January and February 2009 and lasted between 25 and 35 minutes.

Data analysis

All focus groups were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using a constructive process of thematic content analysis. This involves reading and re-reading interview transcripts in order to identify and develop themes and theories emerging from or 'grounded in' the data.15

Analyses of the data were also validated using a process of 'inter-rater reliability' within the research team (RH, WR and PG). This is a process whereby at least two researchers analyse the data separately before agreeing on a thematic framework. It has been argued that the involvement of additional experienced qualitative researchers may help to guard against the potential for lone researcher bias and help to provide additional insights into theme and theory development.16,17

Ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University Research Ethics Committee [FESG 08/41].

Results

The teaching of OHE delivery at undergraduate level

Limitations in the teaching of OHE delivery at undergraduate level were consistently identified. The FD1s felt that the skills acquired in dental school for delivering OHE were not applicable to general dental practice and that this reflected a lack of realism in undergraduate teaching. The problem was perceived as being rooted in the fact that in general dental practice there are greater time constraints than as undergraduates.

'It comes down to time. I think in the dental school you'd think, “Well, you know, I've got all this time, OHI, spend a lot of time on this.” And in practice I think we've got [...] other priorities.' (FD1 2E A)

Having sufficient time in order to teach patients all they need to know to achieve oral health was seen as being fundamental in the effective delivery of OHE. As such, the FD1s felt that in general dental practice they were now unable to practice the 'gold standard' learned in dental school.

'Compared to dental school, I wouldn't want to spend half as much time on it as I would have done if, you know, if you're in dental school you can spend time talking about it, whereas I tend to think, 'I've got half an hour, I've got other work to be doing, and I kind of squeeze it in [...]' (FD1 2A A)

As undergraduates the teaching of prevention was focused on specific clinics such as paedodontics and periodontics. There seemed to be little attention given to OHE or prevention in adult dental care.

'I think we mainly concentrated on prevention in paediatric dentistry and didn't really cover it for adults that much.' (FD1 3B A)

The term 'prevention' was largely used to describe the teaching of physical clinical procedures with less attention given to the non-tangible education of patients. When discussing OHE in the context of adult patient care it was perceived as being peripheral to dental 'treatment', and not valued by staff.

'We were generally taught that when you write a treatment plan the first point was always OHI (oral hygiene instruction). I don't know if it was ever done.' (FD1 2A A)

'On the adult clinics there wasn't an emphasis from members of staff regarding prevention. They wanted diagnosis and then your treatment plan and if you said oral hygiene instruction then they'd skip over it and then, do you know what I mean? It wasn't that much emphasis.' (FD1 1B A)

FD1s felt that guidance on the delivery of OHE had been ambiguous. The methods taught for the delivery of OHE included the use of models for teaching rather than patient involvement.

'You'd have, someone that, I'm not even sure was a dentist [...] she talked us through it [...] it was reasonably useful but I suppose we all knew how to brush our teeth [...] they had loads of lovely models (of teeth).' (FD1 1A C)

Factors influencing the 'frequency and content' of OHE delivery

There were three main influences on the frequency and content of OHE delivery: time available, the presence of disease and outcomes of previous OHE efforts.

Time was seen as the major factor in determining whether OHE was given and how much attention it received. There was a belief that it was necessary to dedicate a large amount of clinical time to OHE in order for it to be effective. However, it was perceived that there was no financial reward within the NHS system for dedicating the necessary clinical time. Therefore there was an unwillingness to use clinical time doing something that was viewed as altruistic. A suggested solution to this was a direct financial reward for time spent delivering OHE.

'For some we need loads of time. You just make time [...] when it is worth it. You know we don't get paid for giving OHI, do you? You spend time doing the things that you do get rewarded for in the [...] system [...]' (FD1 2F A)

OHE activity was predominantly described as being reactive. Participants described how they would spend time educating patients if they had pre-existing disease such as caries or periodontal disease. In some cases OHE was only carried out for patients that were disease active.

'If they've got caries or perio, I explain what that is, briefly, a vague description, and then say what you can do about it [...] I tend to do it when, whenever they've got a problem.' (FD1 3B A)

Outcomes of previously delivered OHE would influence whether a further attempt at delivering OHE would be made. It was reported that if it was possible to achieve better success rates then further delivery of OHE would be more likely.

'I've got loads of people with perio. disease and you look back in the notes at all the treatment and every time it's OHI, OHI, OHI, lost cause [...] you're not going to waste your breath going on and on.' (FD1 2A A)

The barriers to 'effective and successful' OHE

Four barriers were identified to the delivery of effective and successful OHE: time available, patients' ability to recall information, patient motivation and compliance, and finally communication barriers.

Time availability was consistently identified as the major barrier to providing successful OHE. FD1s felt that it was necessary to deliver all the information required during a single session. If this was not possible the OHE was perceived as being substandard.

'Initially you give the main bulk of the advice at the first appointment when they're a new patient or when they first present to you.' (FD1 4D C)

However, it was recognised that it is not possible for patients to recall large amounts of verbal information when communicated in a single episode. The patients' interest in what had been said was also seen to affect the ability of the patient to recall the information given.

'Cause how much do they take in as well? You know, if you've got five different points to tell them about, you know, brushing your teeth, flossing, whatever.'(FD1 2F A)

Factors that motivated patients to change their behaviour were seen as being inherent personality traits and not subject to change through external influences. As such it was the patients who were seen as the drivers for change rather than the dentists.

'I think the major factor for [...] people responding is just their personality [...] that's the overall factor.' (FD1 1C A)

Despite this belief a simplistic approach to influencing patients' behaviour was described. It was repeatedly reported that a single factor could motivate a patient sufficiently to cause a change in behaviour. The threat of a negative experience was seen as being the primary source of motivation. The principal reasons identified were fear of further work, fear of tooth loss, poor aesthetics and the embarrassment of having poor oral hygiene. There was a general perception that a lack of motivation was responsible for a lack of change and that finding and using the factor that would stimulate that motivation would result in change. The dentists' role was described as being able to identify these vulnerabilities and use them to influence the patients' health behaviours.

'It's finding something that causes them to change. And chances are, throughout someone's life it's going to be different things which they emphasise as being important.' (FD1 1A C)

Patients were perceived as being 'good' or 'bad' depending on their history of compliance with preventive advice. It was viewed as being impossible to change the oral health habits of a large group of patients who were labelled 'non-changers.' In contrast, participants felt that the brief time period for which they had been seeing their patients made it difficult to assess whether they had been successful in their OHE delivery.

'I think in some cases you've got an absolutely hopeless patient you just can't change.' (FD1 3A A)

The data suggested that many FD1s felt uncomfortable in the role of educator. Participants frequently voiced concern about whether they sounded patronising, thus compromising the dentist-patient relationship. The most common examples reported were dealing with older age groups or when educating parents in caring for their children's teeth. Patients with a low level of intelligence and education were seen as difficult in communicating with as they were unable to understand the information given.

'It's the older patients that don't tend to respond very well because it's quite difficult to tell them to brush their teeth without being patronising or getting on their nerves.' (FD1 3B A)

Discussion

While the participants were steered in the direction of OHE during the focus groups, their awareness of OHP was also evident from the discussion.

The results of this qualitative research suggest two things in relation to the delivery and understanding of OHE. The first is that the methods used to communicate OHE to patients are not based on the best available evidence. The difficulty of communicating the OHE message appropriately has been reported in the literature18,19,20 and is demonstrated by the findings of this study. The second is that OHE appeared to be considered synonymous with OHP in its delivery. The terms prevention and OHE were not understood as separate entities under the OHP umbrella. Furthermore, the word prevention itself was used as a contradiction in terms by most participants as it was most commonly used to describe activities relating to the treatment of existing problems. This research suggests that what is perceived as OHE delivered to individuals is focused on tertiary rather than primary and secondary prevention. This could perhaps be more aptly named reaction rather than prevention.

Compliance and acceptance

It is important to discuss the definition blurring between OHE and OHP as this presents a potential problem to the delivery of effective prevention for individual patients. As there is no evidence of OHE/OHP being causally related to changes in behaviour,21 then there is a danger that clinical practice may develop along a pathway that accepts the determinants of oral health as outside the control of the individual. In this situation the clinician may feel that it is unrealistic to expect compliance from individuals from labelled subgroups. The prevailing attitudes to OHE/OHP have been demonstrated by the data from this study. As a result there may be greater reliance by GDPs on public health strategies outside the control of the individual: for example, water fluoridation for the delivery of prevention. However, while these measures may have the positive effect of improving overall community dental health, they may have less effect on the inequalities that exist within that community as the distribution of disease within the community remains static.22 The development of primary preventive strategies utilising fluoride toothpaste at the individual level suggests that an individual approach is valued by dental publichealth specialists.23,24

New ways of working

OHE will be used in communicating the appropriate messages but wider strategies will be needed for prevention (primary, secondary and tertiary) in order to satisfy OHP. Clinical preventive techniques (fissure sealants, fluoride varnishes etc) are a given but wider strategies will include measures such as observation of NICE recall guidelines in order to improve community access, as well as encouraging patients' commitment to ongoing care, particularly from deprived subgroups. This would involve a leadership role directing the whole dental team in delivering an integrated organisational approach. Only once was the service of a hygienist mentioned in all focus groups. In that context the hygienist was seen as the person responsible for OHE rather than an integrated role within a strategy for improving oral health.

The research suggests that OHE delivered in practice is compartmentalised and based on an outdated concept of 'dental fitness'. The limitations of OHE must be accepted in order to develop the patient's ongoing dental career. It would be both unrealistic and at odds with good behavioural management, to attempt to achieve total behavioural compliance from patients too soon.25

As such the delivery of OHE in general dental practice was seen as being fraught with difficulties. The most significant problem for the delivery of OHE that was reported was the disparity in the time required to deliver 'gold standard' learned as an undergraduate and the time available in general dental practice. The problem of time was inextricably linked with the opinion that dentists were not rewarded for these lengthy periods needed to deliver OHE. This reflects the views expressed by general dental practitioners regarding rewarding prevention in the new contract of 2006.4,5 However, the evidence base suggests that any educative intervention should be brief and opportunistic in order to be effective.25,26 The FD1s could recognise this as a result of subjective experience but it was in direct contradiction with what they had learnt as undergraduates.

Changing behaviours

The participants also demonstrated the commonly held belief that behaviour change is a linear and a given process following the transfer of knowledge. This theory of behaviour change has long been discredited by behavioural scientists. It is more realistic and accurate to consider behaviour change as something that happens over a period of time, throughout which the GDP practices prevention, using OHE at appropriate intervals.27,28 To facilitate behaviour change goals set by clinicians for patients should be appropriate to the individual's situation and realistically achievable. This in turn translates into simple specific unambiguous messages delivered in a strategic manner within a time frame, the patient's dental career. In the context of the association between attendance and deprivation,29 the first simple specific message should be 'for the individual to attend' and this should be facilitated through organisational processes. This should be a fundamental element of the OHP policy of a preventive General Dental Practice. Once in an ongoing care pathway, further layers of communication can be added to improve understanding of disease processes and their control. This has been described by Milsom et al. as a 'holistic approach'.30 This pathway of events does not fit easily into a definition of dental fitness and a single course of treatment and compartmentalised, independent episodes of OHE. Milsom et al. highlight the ability of the new contract of 2006 to facilitate a holistic approach.30 However, if we consider the 'gold standard' methods for the delivery of OHE as perceived by the FD1s, it is understandable why it was reported that there is no reward for OHE, an opinion compounded by the emphasis and value placed on OHE as undergraduates.

Evidence and direction

Threlfall et al. reported that the new dental contract provided an opportunity for change by placing prevention at the heart of dental care.31 His team also reported that this opportunity would be wasted if an improvement in the under- and postgraduate teaching of counselling skills and educative techniques, for example 'the conveying of bad news' or motivational interviewing, did not occur. The participants' understanding of OHE gleaned from undergraduate education suggests that this has been the case. The reported perceived value placed on OHE as a result of the undergraduate experience and the lack of discussion of counselling and educative techniques also support Threlfall's views.

The participants' reports of behavioural science education as undergraduates were significant in their absence from the discussion. Although behavioural sciences have a place in the undergraduate curriculum, the graduates take away from their undergraduate experiences little in the way of sound theoretical frameworks as applied to the clinical setting: for example, the expectation of the clinician that behaviour change should occur following knowledge transfer, with resultant feelings of failure with observed non-compliance. Stillman-Lowe reported that the lack of development in the quality of OHE in general practice was partly due to the lack of specific guidance on the delivery of OHE in dental practice.6 This appears to be the case even before dentists have qualified and begun to practice. As a result many of the reported techniques are the result of human instinct rather than a technique based on evidence.

Despite these instincts being sometimes good and beneficial to the patient, the ad hoc approach to OHE often meant that messages delivered were threatening, negative and potentially damaging. This could explain the reported effects of historic OHP activities in increasing social inequalities.21,32 Attempts at changing patients' behaviour were usually based on the 'Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviour' model of behaviour change. This was coupled with the belief that the application of a motivating factor or threat at the knowledge stage would ensure progression along the linear pathway to change. Sheiham and Watt have stated that a 'simplistic and outdated approach' had dominated OHE for many years. It appears that the groups studied continue to utilise this approach.33

Such attitudes mirror the limitations of dental health education identified by Croucher over 15 years ago.34 Such beliefs in the workforce of the future suggest a real possibility that such attitudes and approaches will continue to prevail. The belief that the dentist should find the one key motivating factor that could stimulate change again suggests the lack of awareness of the complexity of challenging human behaviour that was reported by Sheiham and Watt (2003).33

Little seems to have changed since Blinkhorn (1998) reported that dentists' enthusiasm for prevention faded quickly, with dentists tending to be disease centred rather than patient centred.35

Concluding remarks

This small qualitative study suggests that there is an awareness of the difference between OHE and OHP but that the difference is not understood as a reality in terms of its role in general dental practice. OHE is often compartmentalised and a simplistic approach is taken to its delivery. The delivery of OHE by the FD1s is not based on the best available evidence. It also suggests that professional experiences socialise towards an acceptance of past experiences and limited success with regard to OHE, particularly with some individuals.

OHE is fundamental to communicating appropriate information to patients that attend general dental practice and, along with organisational processes that facilitate ongoing continuing care, forms the basis of prevention in primary, secondary and tertiary forms. If dentists are unaware of the best available evidence on its delivery it is unlikely that individual recipients of care will be adequately briefed in order to act in an appropriate manner, particularly those sub-groups with the greatest needs who traditionally utilise services least.

Against a backdrop of commissioning to improve health this has implications in developing organisational processes within general dental practice and training in order to achieve this.

Further research is needed to establish whether the themes that emerged in this small study can be generalised to a larger population of FD1s and GDPs. If generalisable, an opportunity exists for transferable skills to be taken from other disciplines and taught at both under- and postgraduate level to address this situation.

References

Levine R S, Stillman-Lowe C R. The scientific basis of oral health education. London: BDJ Books, 2009.

General Dental Council. The first five years. London: General Dental Council, 2009. http://www.gdc-uk.org/NR/rdonlyres/B7C2479E-61A4-4962-B109-26928C0E8034/91355/TFFYthirdeditionfinal1.pdf. Accessed 3 November 2010.

Diploma of the fellowship of the faculty of general dental practice (UK) curriculum. Standards of competence. FGDP(UK). http://www.fgdp.org.uk/_assets/pdf/career%20pathway/step%20by%20step%20guide/ffgfp_curriculum_clinical.pdf. Accessed 2 March 2010).

Department of Health. NHS dental services in England: an independent review led by Professor Jimmy Steele. London: DH Publications, 2009.

Community Dental Service sub-group of the Welsh Assembly Government. Welsh Assembly Government task and finish group review of the National Dental Contract in Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government, 2008. Available at http://wales.gov.uk/docs/phhs/meetings/cdsjuly08/100708cdsrecommenden.doc. Accessed 3 November 2010.

Stillman-Lowe C . Oral health education: what lessons have we learned? Br Dent J 2008; Supplement 2: 9–13.

Downie R S, Fyfe C, Tannahill A . Health promotion: models and values. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Department of Health. Improving oral health with the new dental contract. London: Department of Health, 2006.

Richards W, Gear T . Changes in the balance between dentists, patients and funders in the NHS and their consequences. Prim Dent Care 2008; 15: 13–16.

Evidence summary: what do dentists mean by 'prevention' when applied to what they do in their practices? Br Dent J 2010; 208: 359–363.

Silverman D . Doing qualitative research. London: Sage Publications, 2000.

Pope C, Mays N (eds). Qualitative research in health care. 3rd ed. London: BMJ Books, 2006.

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B . Methods of data collection in qualitative research. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 291–295.

Morgan D L . The focus group guide book. London: Sage Publications, 1998.

Burnard P, Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B . Analysing and presenting qualitative data. Br Dent J 2008; 204: 429–432.

Cutcliffe J R, McKenna H P . Establishing the credibility of qualitative research findings: the plot thickens. J Adv Nurs 1999; 30: 374–380.

Barbour R . Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog? Br Med J 2001; 322: 1115–1117.

Beal J F . Social factors in preventive dentistry. In Murray J J The prevention of dental disease. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

Threlfall A G, Milsom K M, Hunt C M, Tickle M, Blinkhorn A S . Exploring the content of the advice provided by general dental practitioners to help prevent caries in young children. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E9.

Department of Health and the British Association for the Study of Community Dentistry. Delivering better oral health: an evidence-based toolkit for prevention. London: Department of Health, 2007.

Kay E J, Locker D . Effectiveness of oral health promotion: a review. London: Health Education Authority, 1997.

O'Mullane D, Whelton H . Caries prevalence in the Republic of Ireland. Int Dent J 1994; 44: 387–391.

Childsmile Core Programme. NHS Scotland. www.child-smile.org.uk/professionals/childsmile-core.aspx. Accessed 2 March 2010.

Designed to Smile Programme. Welsh Assembly Government. www.designedtosmile.co.uk/dentists.html. Accessed 2 March 2010.

NICE. Behaviour change at population community and individual levels. 2007 Guidance 6. Accessed online at http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11868/37987/37987.pdf. Accessed 2 March 2010.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Brief interventions and referral for smoking cessation in primary care and other settings (Public health intervention guidance 1). London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006.

Jacob M C, Plamping D . The practice of primary dental care. London: Wright, 1989.

Elderton R J (ed). Positive dental prevention: the prevention in childhood of dental disease in adult life. London: Heinemann Medical, 1987.

Evidence summary: what is the effectiveness of alternative approaches for increasing dental attendance by poor families or families from deprived areas? Br Dent J 2010; 208: 167–171.

Milsom K M, Jones C, Kearney-Mitchell P, Tickle M . A comparative needs assessment of the dental health of adults attending dental access centres and general dental practices in Halton & St Helens and Warrington PCTs 2007. Br Dent J 2009; 206: 257–261.

Threlfall A G, Hunt C, Milsom K, Tickle M, Blinkhorn A S . Exploring factors that influence general dental practitioners when providing advice to help prevent caries in children. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E10.

Sprod A J, Anderson A, Treasure E T . Effective oral health promotion: literature review. Technical report 20. Cardiff: Health Promotion Wales, 1996.

Sheiham A, Watt R . Oral health promotion. In Murray J J, Nunn J H, Steele J G (eds.) The prevention of oral disease. 4th ed. pp 243–257. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, 2003.

Croucher R . General dental practice, health education, and health promotion: a critical reappraisal. In Schou L, Blinkhorn A S (eds) Oral health promotion. pp 153–168. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Blinkhorn A S . Dental health education: what lessons have we ignored? Br Dent J 1998; 184: 58–59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Humphreys, R., Richards, W. & Gill, P. Perceptions of first year foundation dentists on oral health education and its role in general dental practice. Br Dent J 209, 601–606 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.1133

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.1133

This article is cited by

-

General dental practitioners’ approach to caries prevention in high-caries-risk children

European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry (2021)

-

Lost in transition - changes in communication in the leap from dental student to foundation dentist

British Dental Journal (2011)

-

An effective oral health promoting message?

British Dental Journal (2011)