Abstract

This article draws on different strands of existing scholarship to provide an analytical framework for understanding the barriers to achieving a well-being economy. It explores the interplay between agential and structural power, where some actor-coalitions can reproduce or transform pre-existing structures. Conversely, these structures are strategically selective, favouring some actors, interests, and strategies over others. Making sense of this interplay between agential and structural power, the article introduces the notion of power complexes—time-space-specific actor-coalitions with common industry-related interests and the power to reproduce or transform structures in a given conjuncture. To understand the historical “becoming” of today’s political-economic terrain, the article provides a regulationist-inspired history of the rise, fall, and re-emergence of four power complexes: the financial, fossil, livestock-agribusiness, and digital. They pose significant threats to pillars of a wellbeing economy such as ecological sustainability, equ(al)ity, and democracy. Subsequently, today’s structural context is scrutinised in more detail to understand why certain actors dominate strategic calculations in contemporary power complexes. This reveals strategic selectivities that favour multi- and transnational corporate actors over civil society, labour movements, and public bureaucracies. The article then examines firm-to-state lobbying as a strategy employed by corporate actors within today’s structural context to assert their interests. It presents illustrative cases of Blackstone, BP, Bayer, and Alphabet. Finally, it explores implications and challenges for realising a wellbeing economy based on post-/degrowth visions. It emphasises the double challenge faced by such a wellbeing-economy actor-coalition. On one hand, it has to navigate within contemporary modes of regulation that favour corporate strategies of capital accumulation while, on the other, it must confront the self-expanding and extractive logic of capital. In this context, three key challenges are outlined: the need to form unconventional strategic alliances, operate on various spatial dimensions simultaneously, and institutionalise alternatives to firm-to-state lobbying to influence policymaking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The wellbeing economy is an emerging concept aimed at overcoming the goal of undirected economic growth as a signifier of wellbeing and prosperity (Costanza et al., (2018); Jackson, 2021). Instead, it seeks to direct economic activities towards enhancing human and ecological wellbeing while promoting a fair distribution of resources, income, and wealth (Büchs et al., 2020; McCartney et al., 2023). The idea of a well-being economy has attracted growing support among a wide variety of actors, including sections of governments, civil society, international organisations, and businesses (see, e.g., WEAll n.d.). This interest has emerged despite—or rather because of—different interpretations of the term as well as diverging approaches to what to do and how to go about it (Mason and Büchs, 2023; Hayden and Dasilva, 2022; Waddock, 2021). While some actor-coalitions highlight the radical and transformative dimension of a wellbeing economy that resonates with post-/degrowth visions (e.g., Fioramonti et al., 2022; EEB, & Oxfam Germany 2021), others consider it an incremental approach to promote “green” and “inclusive” growth (see Godziewski, 2021).

However, although the struggle to realise a particular vision of a wellbeing economy inevitably occurs in time-space-specific political-economic conjunctures, the analysis thereof lacks attention and scrutiny in wellbeing-economy research. As a result, the complexity of and the obstacles to realising a wellbeing economy tend to be underestimated. This applies in particular to a wellbeing economy based on de-/post-growth visions, which are not confined to “greener” or “more inclusive” accumulation strategies but entail forms of planned disaccumulation in specific economic sectors (Hickel, 2021). In contrast to green-growth versions of a wellbeing economy, post-/degrowth radically challenges the hegemonic understanding of the economy and of economic practice, and is therefore confronted with difficult questions. What kind of alliances are possible and necessary here and now? At what levels must strategic action be taken? And what form of agency can drive transformative change?

Addressing these questions, this paper draws on different strands of existing scholarship to provide an analytical framework for understanding the barriers to achieving a wellbeing economy. In so doing, it is grounded in critical-political-economy literature and in secondary sources to show how political-economic struggles take place in a contested terrain in which agential and structural power are entwined. While different actor-coalitions have different resources at their disposal to assert their visions and interests, they also compete within a given time-space-specific power structure (Bhaskar, 1998). In such a pre-structured world, agential power never creates structures ex nihilo but reproduces or transforms them (ibid). Struggles always occur within structural contexts, but as these are themselves the condensation of previous struggles, structures are “strategically-selective”—they privilege “the access of some forces over others, some strategies over others, some interests over others, some spatial and temporal horizons over others” (Jessop, 1999, 54f). As structural power is strategically-selective, agential power is “structurally-constrained, more or less context-sensitive, and structuring” (Jessop, 2005, 48). Consequently, understanding the contested terrain in which struggles over a wellbeing economy occur requires both an analysis of the strategically-selective structural context as well as the “(differentially reflexive) structurally-oriented strategic calculation” of powerful actor-coalitions (ibid., 48).

To do so, this paper introduces the notion of power complexes. They represent actor-coalitions that are powerful within a given structure, either reproducing or transforming it. More precisely, we understand a power complex as a coalition between actors (be it fractions of capital or other social groups) with shared industry-related interests. These power complexes are time-space specific and not always internally coherent. Moreover, in different spatiotemporal conjunctures (characterised by specific strategic selectivities), some industry-specific actors—certain groups of firms, workers, state institutions, or civil society—are more powerful than others and thus dominate strategic calculations (Jessop, 2015). Power complexes are, therefore, the spatiotemporal interplay of agential and structural power. Rooted in critical political economy, we understand power complexes as part of a hegemonic bloc, which, conversely, consists of several industry-specific power complexes. Based on these conceptual considerations, this paper addresses four related research questions:

-

1.

How have power complexes been able to exercise agential power within and through time-space-specific power structures?

-

2.

Which actors are dominant in today’s power complexes, and why?

-

3.

What are their key strategies?

-

4.

What are the implications and challenges for realising a wellbeing economy based on post-/degrowth visions?

The attempt to answer these questions structures our argument. Section “The spatiotemporal co-evolution of structural and agential power: a brief history of the rise, fall, and re-emergence of power complexes” provides a regulationist-inspired history of the rise, fall, and re-emergence of four power complexes: the financial, fossil, livestock-agribusiness, and digital. It briefly illustrates how these power complexes have exercised agential power within and through historically specific modes of regulation. The section ends by suggesting that contemporary power structures favour (multi- and transnational) corporate actors, who therefore dominate strategic calculations in contemporary power complexes. Based on this, Section “Corporate strategies to exercise power: firm-to-state lobbying” focuses on a key corporate strategy—firm-to-state lobbying—and introduces a heuristic to study it. Section “Analysis: cases of firm-to-state lobbying” draws on secondary sources and exemplary cases in each power complex—Blackstone (financial), BP (fossil), Bayer (livestock-agribusiness), and Alphabet (digital)—to employ this heuristic and thereby illustrate key pillars of an analytical framework for studying firm-to-state lobbying. Section “Conclusion: implications and challenges for realising a wellbeing economy” concludes by reflecting on implications and challenges for realising a wellbeing economy based on post-/degrowth visions.

The spatiotemporal co-evolution of structural and agential power: a brief history of the rise, fall, and re-emergence of power complexes

A regulationist approach (Aglietta, 1998; Boyer and Saillard, 2010; Becker, 2002) explores how stability is possible in the inherently crisis-prone capitalist mode of production. Capital’s monetary and metabolic circuits strive to integrate ever more people, regions, and aspects of nature into the accumulation process (Marx, 1983; Luxemburg, 1913; Harvey, 2019). This expansionary logic results in a self-perpetuating accumulation spiral: the more (biophysical) resources are extracted for profit, the more can be extracted in the following round (Malm, 2016, 284; Pirgmaier and Steinberger, 2019). As this ever-intensifying and -expanding process of surplus-value maximisation constantly alters socio-economic and socio-ecological relations, “melting all that is solid into air” (Marx and Engels, 1848/2019; Berman, 2010), it is only viable through social and political regulation of the prerequisites of accumulation, such as a stable monetary system and welfare institutions that reproduce workers. A mode of regulation stabilises, always temporarily, an inherently crisis-prone accumulation regime, i.e., a specific way of organising production with certain technologies, business models, forms of financing, and distribution to turn money into more money. A regulationist-inspired history allows us to identify three historical periods of different modes of regulation: the colonial-liberal regulation from about 1850 until 1929, the Fordist regulation of the post-war period, and neoliberal regulation after 1973 (Novy et al., 2023). A mode of regulation wields structural power. It favours some actors with specific accumulation strategies, giving them agential power to shape regulation. In what follows, we delineate how power complexes have co-evolved with specific modes of regulation.

Colonial-liberal regulation: the rise of the financial power complex

The regulation during the colonial-liberal era from about 1850 until the onset of the world economic crisis in 1929 can be characterised as “free-trade imperialism” (Arrighi, 1994, 47). It followed an extraverted logic of accumulation that extended capitalists’ exploitative and extractive logics to all continents (Becker, 2002). The British Empire was the global hegemon, the largest of the Western colonial powers that together controlled 85% of the planet’s surface in 1914 (Arrighi, 1994, 54). The colonial-liberal regulation was underpinned by the gold-pound standard and legal security for private property, contracts, and debt repayments. Haute finance, a “closely knit body of cosmopolitan financiers” (ibid., 54), functioned “as the main link between the political and the economic organisation of the world” (Polanyi, 2001, 10). The hub of this internationally interwoven banking sector was the City of London (Knafo, 2013), backed globally by the British Navy. 44% of world overseas investment originated from Britain (Hobsbawm, 2003, 51). Even large peripheral states were subjected to intense scrutiny by international investors to ensure debt repayment. For example, the Turkish Ottoman Public Debt Administration and the Roosevelt Corollary enforced debt repayment from the Ottoman Empire and Latin American states (Rodrik, 2012, 39). British “free-trade imperialism” came to an end with the Great Depression in 1929.

Fordist regulation: the decline of the financial power complex, the rise of the fossil and livestock-agribusiness power complexes

Amidst the upheaval of two World Wars, power dynamics shifted, providing the foundation for a new mode of regulation. The 1933 separation of commercial and investment banking in the US weakened the financial power complex (Arrighi, 1994). Simultaneously, corporations like DuPont, Monsanto, and Dow gained influence through the rising demand for explosives in war times (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2017). Companies heavily relying on fossil fuels received substantial subsidies through public infrastructure investments such as highways – Ford in Detroit, Fiat in Mussolini’s Italy, Volkswagen in Hitler’s Germany (Malm, 2021). After World War II, accumulation dynamics shifted from the UK to the US, from finance to manufacturing, and from global to domestic markets (Becker, 2002). Pax Britannica was replaced by pax Americana, with a “free enterprise system” (Arrighi, 1994, 58ff). This geopolitical order of the Cold War was underpinned by the US army as the defender of the “free world” and the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Strict capital controls restrained global financial markets, further weakening the financial power complex. This increased the policy space for nation states, while empowering big business and trade unions nationally (Ruggie, 1982; Novy 2001). It resulted in a growth coalition that ensured social legitimacy and cohesion while intensifying the exploitation of nature. Within countries, socioeconomic inequalities declined, while increasing between countries (Piketty, 2014).

In the Global North, accumulation was stabilised by self-perpetuating cycles of mass production for mass consumption. Large corporations concentrated in sectors with significant fossil-fuel dependency, be it the energy or automotive industries. Fossil fuels were utilised to extract more fossil fuels, and fossil capital recursively intensified its material flow (Pineault, 2022). In 1910, oil represented 5% of world energy; by 1970, it had risen to more than 60% (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2017). Oil companies like Exxon, Chevron, BP, and Shell were politically supported by Western military powers, who resisted decolonial nationalisation efforts, e.g., in the case of BP in the 1950s in Iran.

In the post-war period, also the livestock-agribusiness power complex thrived, industrialising agriculture. In line with war ideologies and efforts to capitalise on previous war investments, pest control shifted from entomology to chemical extermination (Bonneuil and Fressoz, 2017). Fertiliser and pesticide use increased by 1338% between 1935 and 1970 (Moore, 2015, 251). War-developed DDT and sarin became widespread insecticides/pesticides. The Green Revolution introduced capital-intensive technologies, which boosted productivity and output but harmed small farms and biodiversity. The capitalisation of nature accelerated, fuelled “by turning oil and gas into food” (Moore, 2015, 251), marking an era of petro-farming. Since then, increased production in animal feed has led to a surge in livestock, elevating its share in terrestrial mammalian biomass to around 60% (Bar-On et al., 2018). Nearly 60% of global agricultural land is now associated with beef, covering an area almost as large as the US, Canada, and China combined (Hickel, 2022, 219). These trends contribute to wildlife extinction, biodiversity loss, and over 16% of greenhouse-gas emissions (WWF, 2018; FAO, 2019; Twine, 2021). The Fordist regulation, based on the fossil and livestock-agribusiness power complexes, ushered in the Great Acceleration (Steffen et al., 2015; McNeill and Engelke, 2016), which outlived Fordism.

Neoliberal regulation: the re-emergence of the financial and the rise of the digital power complex

The Fordist foundations of the free-enterprise system—characterised by mass production, foreign direct investment, and strict capital controls—led to growing tensions. During Fordism, profit rates surpassed interest rates (Piketty, 2014), low unemployment rates shifted power to trade unions (Kalecki, 1997), and decolonisation started to challenge Western hegemony (Slobodian, 2018). To restore class power, industrialists allied with finance capital, ushering in a financialised mode of regulation. The Eurodollar market contributed to the demise of the Bretton-Woods Agreement—based on fixed exchange rates and strict capital controls—by creating a private market for US dollars in London (Dickens, 2005; Green, 2016). From the 1970s, neoliberal regulation redirected accumulation dynamics towards finance capital (Durand, 2022, 41), resulting in “hyperglobalisation” (Rodrik, 2012) and “financialisation” (Epstein, 2006). The financial power complex, along with global rent extraction, re-emerged. This time, with Wall Street at its centre, the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency, and US government debt securities as the safest assets. After 1979, rising US interest rates and a strong US dollar entrapped many Global-South countries in debt, recentralising Western financial power (Arrighi, 1994, 323). Neoliberal policies constrained the autonomy of nation-states, especially in the Global South, fostering “strong rules and weak states” (Skidelsky, 2019, 376). The emergence of a new global constitutionalism formalised arrangements to defend private property and contracts through private arbitration tribunals (Robé, 2020; Pistor, 2019; Cox, 1994). High capital mobility intensified locational competition, allowing rentiers to extract income and wealth from the public domain, workers, and nature (Stratford, 2020; Mazzucato, 2018). This contributed to rising socioeconomic inequalities and wealth concentration (Piketty, 2014).

While the fossil and livestock agribusiness power complexes maintained their influence, a digital power complex emerged alongside platform-based business models (Srnicek, 2017). Digitalisation became a technological megatrend (Barns, 2020), enabling corporations to process information more efficiently, reduce fixed costs, and further globalise production and communication. Since the 1980s, digitalisation has expanded global production and value chains, enhancing the efficiency of interactions and associated profits (Lange and Santarius, 2018). The digital power complex, dominated by the “Tech Titans” or “Big Five” (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Google), solidified its dominance since the early 2000s Dot-Com Boom and the techno-utopianism of a sharing economy. This era of surveillance capitalism is driven by Big Data as vital raw material in the accumulation process and new ways of predicting and steering human behaviour (Zuboff, 2019). Digital corporations have reshaped business models, consumption patterns, social interactions, and exerted political influence, affecting democratic decision-making (Atal 2020; Barns, 2019; Kenney and Zysman, 2020; Gillespie, 2015; Engin et al., 2020). In neoliberal regulation, for the first time, all four power complexes have interacted, unleashing unprecedented extractive forces—of materials, rents, and data—to accelerate capital accumulation.

The contemporary interregnum

With the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008 and, more recently, the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the resulting cost-of-living crisis, neoliberal regulation has faced increasing challenges, leading to significant departures from past logics (Durand, 2022; van Apeldoorn and de Graaff, 2022; Tooze, 2022; Patomako 2017). Today, we are in what Gramsci (2003, 556) called an “interregnum,” a time when “the old is dying, and the new cannot be born”, giving rise to structural discontinuities and modifications in the strategic calculations of powerful actor-coalitions.

The financial power complex

In response to the post-2008 international economic slowdown, central banks adopted expansive monetary policies of quantitative easing, leading to further asset valorisation and redistribution to the rich (Skidelsky, 2018, 256ff; see also Braun, 2016; Wullweber, 2021). The GFC shifted power within the financial power complex from banks to asset managers (Braun, 2021; Haldane, 2014). Global Assets Under Management (AUM) rose from 84.9 trillion USD in 2016 to 111.2 trillion USD in 2020, with projected 145.4 trillion USD by 2025 (PwC, 2023). Demand for alternative, equity-based assets surged due to relatively low yields in traditional financial instruments like stocks and bonds. Institutional investors, including private equity firms and large asset managers, have increasingly directed investments into “real assets” such as housing, energy, farmland, water, and social infrastructures (Christophers, 2023, 17; Bayliss and Gideon, 2020; Fine et al., 2016; Horton, 2017; Plank et al., 2023). Consequently, the financial power complex has undergone a process of restructuring with new players consolidating their power (Braun and Koddenbrock, 2022). Despite the financial sector’s public commitment to “greening investments” through Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) and Green Taxonomies, this has often resulted in changed accounting rules without substantial shifts of investment patterns (InfluenceMap, 2023a). Since the Paris Agreement, the financial sector has funded and facilitated the issuance of over one trillion euros of bonds by fossil-fuel companies (Joosten et al., 2023).

The fossil power complex

Following the GFC, economic and political factors prompted caution within the fossil power complex. Declining profits from low fuel prices after 2011 (Wilson and Hook, 2023) and expected government barriers to fossil infrastructure investments due to pressure from climate movements were major concerns (Zeller, 2023). This changed with the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Rising energy prices shifted public opinion to short-term issues, and geopolitical block formation led to a securitisation and militarisation of energy politics. Securing energy access increasingly takes precedence over decarbonisation (Engels et al., 2023). European governments have expanded their liquefied natural gas (LNG) infrastructure, and fossil-fuel companies present gas as a clean alternative (Si et al., 2023). After a few less profitable years and restrained investment, fossil-fuel companies are making record profits, boosting investments in fossil infrastructure, and retracting climate pledges (Zeller, 2023). ExxonMobil, Shell, Chevron, TotalEnergies, and BP more than doubled their profits in 2022, investing only a fraction in low-carbon energies (InfluenceMap 2022a) and opting for increased share buybacks and dividends (Sharma, 2023; International Energy Agency IEA 2023, 61–62). This fossil-based development path is reinforced by increasingly harsh state repression against climate activists and by climate research that underestimates emissions and overestimates the potential of negative-emission technologies (Achakulwisut et al., 2023; Stoddard et al., 2021; Anderson, 2015; Bukold, 2023; Dyke et al., 2021). Fossil capital seems set to embark on a new round of accumulation, pushing for further lock-ins of the fossil energy system (IPCC, 2022, 267; International Energy Agency IEA 2021).Footnote 1

The livestock-agribusiness power complex

The worsening climate crisis jeopardises food security due to reduced crop yields (IPCC, 2023, 50). This empowers calls for climate-resilient genetically modified (GM) crops (Nishimoto, 2019, 145), which heavily rely on pesticides (Benbrook, 2012; Goodman, 2023). The trend towards increased pesticide use is, once again, supported by the financial power complex, with major investment firms funnelling around 4.12 billion USD into lobbying for pesticide deregulation (Castilho et al., 2022). Agricultural subsidies, surpassing 851 billion USD annually (OECD, 2023, 21), tend to favour emission-intensive and unhealthy products with negative impacts on the environment and human health (FAO et al., 2021). While Covid-19 outbreaks in meat-processing factories exposed scandalous environmental and labour conditions in mass meat production (Ban et al., 2022), the livestock industry remains powerful, contributing significantly to investment and employment in certain regions (Sievert et al., 2020, 7). Russia’s invasion of Ukraine revealed the vulnerability of global food supply chains and the reliance on Ukraine as one of the world’s “breadbaskets,” leading worldwide to higher food prices and hunger due to reduced crop yields and disrupted transport (European Council, 2023; Wong and Swanson, 2023). In response, agribusiness lobbied for relaxed environmental regulations (Cann, 2022). Despite scientific evidence of the livestock agribusiness industry’s climate impact (Lazarus et al., 2021) and damage to biodiversity (Tang et al., 2021), it has remained successful in exploiting fears of economic instability and food insecurity.

The digital power complex

Digital corporations, once at the heart of “progressive neoliberalism” (Fraser, 2019) and key players in the liberal globalism of the Obama era, have witnessed a shift towards national capitalism (Novy, 2022). This is marked by new, outright anti-democratic alliances within the digital power complex. Figures like Elon Musk and venture capitalist Peter Thiel openly criticise democratic institutions and advocate for a power transfer to start-ups and billionaires (Gumbel, 2022; Chafkin, 2022). This anti-democratic trend, however, is only the culmination of long-term threats to democracy posed by digital corporations, raising increasing concerns about misinformation, micro-targeting, algorithmic amplification, lack of transparency, and foreign interference in elections (Zuboff, 2019; Cadwalladr and Graham-Harrison, 2018). Simultaneously, state surveillance has increased, affecting citizenship and justice, promoting social sorting through predictive policing, and reinforcing self-censorship (Earl et al., 2022; Loewenstein, 2023). Moreover, digital corporations provide critical digital services, thereby often replacing publicly governed infrastructures and concentrating control among a few profit-driven actors (Digitalisation for Sustainability D4S 2022). The increased digital interconnectedness during the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated this trend (Döhring et al., 2021). This is exemplified by Google’s data-sharing deal with the NHS in the UK, which raised concerns about the handling of patient data (Fitzgerald and Crider, 2020) and indicated how public services increasingly rely on private digital infrastructures (Krisch, 2022). However, growing concerns about data concentration and political influence have prompted regulatory action. Australia and Canada introduced legislation against misinformation, the UN developed a Digital Cooperation Roadmap, and the EU introduced the Digital Services and Markets Acts. Major tech companies were fined, e.g., Google for antitrust violations and Meta for user tracking. Shifting away from initial euphoria, scepticism has grown about the addictive, monopolistic, and destructive tendencies of the ‘Tech Titans’, who increasingly threaten democracy (Magnuson, 2022).

In summary, this brief regulationist history indicates how structures, conceptualised as modes of regulation, have their own emergent properties and material effects, e.g. on the climate, democracy, and inequality, but are simultaneously instable and impermanent, requiring actor-coalitions to perform appropriate practices to reproduce (or transform) them. Thus, while structural and agential power co-evolve, they are distinct, with successful actor-coalitions being able to reflect on structural contexts in their strategic calculations. At the same time, their capacity to act—to reproduce or transform pre-existent structures—depends not only on strategic calculations and the resources they control but also on their position within existing structures, which favour some strategies and actors over others. An example is the reduced influence of the financial power complex during Fordism.

Today, neoliberal regulation is eroding, but the four power complexes are solidifying their agential power, albeit partly reconfigured. They pose a significant threat to key pillars of a wellbeing economy such as ecological sustainability, equ(al)ity, and democracy. Moreover, in the current conjuncture, contemporary regulation continues to favour (multi- and transnational) corporate actors while disadvantaging civil society, labour movements, and public bureaucracies. This has several reasons. For example, the high technical complexity and multi-scalarity of policy processes—where actors (with specific forms of expertise) must simultaneously act on different levels—pose challenges for trade unions and civil-society actors (Swyngedouw, 2011; Becker and Novy, 1999). This is accompanied by structural barriers for alternative civil-society actors and transformative climate science to access spaces of influence (Spash, 2020; Stoddard et al., 2021; Sultana, 2022). Additionally, despite tendencies of deglobalisation (Novy, 2022; van Bergeijk, 2020), capital mobility remains high. Locational competition disadvantages workers, whose agential power—in contrast to that of large corporations—is strongly rooted in localities and national institutions. Moreover, processes of downsizing and the outsourcing of expertise to private consultancy firms have substantially weakened the knowledge base of public bureaucracies, curtailing their agential power (Mazzucato and Collington, 2023). Therefore, ongoing progressive developments—e.g., the broadening discourse on contemporary crises (e.g., “Beyond Growth Conference 2023” in the European Parliament), a rise in industrial action (e.g., Prescod 2023), and increasingly challenged narratives of post-administrative states (Foundational Economy Collective, 2020)—are confronted with a structural context in which corporate actors have become strongly anchored in the state, exhibiting significant control over relevant state apparatuses and processes. This leads to our third research question: what are corporate actors’ key strategies to exercise power?

Corporate strategies to exercise power: firm-to-state lobbying

Corporate actors dominate the strategic calculations of power complexes in the current interregnum, thereby pursuing various strategies to exercise agential power. These include founding thinktanks (e.g., Almiron et al., 2022; Franta, 2022; Plehwe, 2023), hiring PR firms (e.g., Cooke, 2023; Brulle and Werthman, 2021; Almiron and Xifra, 2021; US House of Committee on Natural Resources, 2022; Oreskes and Conway, 2011), championing finance taxonomies to facilitate green and social washing (e.g., Gabor and Kohl, 2022), promoting academic programmes such as neoclassical economics and law to protect core capitalist institutions (e.g., Mayer, 2016; Teles, 2012; Söderbaum, 2008), donating to political candidates and campaign finance (e.g., Lazarus et al., 2021; Brulle and Downie, 2022), and influencing the media, e.g. to frame the climate crisis as a problem of markets and technology or the reduction of meat consumption as an elitist agenda (Painter et al., 2023; Theine and Regen, 2023; Sievert et al., 2022). These strategies—actualised in strategically-selective structures—influence political agenda-setting as well as social norms and ideas, often leading to discourses of ‘climate delay’ (Lamb et al., 2020; Si et al., 2023). In what follows, we focus on one specific corporate strategy to exercise agential power: firm-to-state lobbying.

Firm-to-state lobbying has always been an important corporate strategy to influence regulations, including during neoliberalism (Hofman and Aalbers, 2017; Fuchs and Lederer, 2007; Hanegraaff and Poletti, 2021). In this period, strategic selectivities emerged from globalised trade and finance, favouring multi- and transnational corporate actors (often with ties to global institutions like the WTO and the IMF) over those anchored in places or certain territorial, especially nation-state, institutions. The uneven distribution of resources is also apparent in lobbying spending, as the spending ratio between corporations and labour unions/public-interest groups in the US is up to 35 to 1 (Drutman, 2015). This trend is mirrored in Europe, where corporate lobbying conspicuously outweighs that of labour (Porak, 2023). Here, it is worth noting that political party contributions, while being closely related to firm-to-state lobbying, are generally not considered a form of lobbying per se but rather a form of political fundraising. In this context, Brulle and Downie (2022, 14) suggest that the considerably higher spending on lobbying than on political contributions indicates that the former is viewed as more effective (see also Brulle, 2020). The latest IPCC assessment recognises the threat of industrial lobbying for climate-change mitigation (IPCC, 2022, e.g., Working Group 3, Chapter 5) and international organisations have addressed its repercussions on inequality (e.g., UNDP 2021; Pachón and Brolo, 2021) and democracy (e.g., OECD, 2021). Nevertheless, lobbying as a research object has remained widely absent in debates on a wellbeing economy. For the remainder of this article, we seek to contribute to addressing this gap by enhancing the analytical understanding of firm-to-state lobbying.

Synthesising lobbying theories, Hofman and Aalbers (2017) propose a conceptual framework to analyse firm-to-state lobbying, thereby providing a useful heuristic. They define firm-to-state lobbying as a relational socio-spatial practice of firms aiming “to alter, influence, or hamper the decision‐making process of governments” (ibid, 1). This practice involves actions geared towards mobilising both material (e.g., money, labour) and immaterial resources (e.g., a firm’s reputation, national champion status, know-how, authority). Mobilising these resources enables firms to activate power and access spaces of lobbying. From a regulationist perspective, corporate lobbying as a socio-spatial strategy plays a significant role in reproducing or transforming a mode of regulation. Inspired by this heuristic, we formulate four guiding questions to analyse firm-to-state lobbying, summarised in Table 1.

Analysis: cases of firm-to-state lobbying

This section draws on secondary sources to explore firm-to-state lobbying, featuring key corporate players in each power complex: Blackstone (financial), BP (fossil), Bayer (livestock-agribusiness), and Alphabet (digital). As four in-depth case studies are beyond the scope of a single paper, the following analysis rather draws on selective examples and secondary sources to illustrate key pillars of an analytical framework for studying firm-to-state lobbying. In this context, focusing on individual corporations permits the “study of individual organisational behaviours” (Brulle 2018, 294), which is often overlooked in sector-based approaches that ignore sectoral heterogeneity and intra-sectoral competition (Kim et al., 2016; Downie, 2019). As stated earlier, we treat political party contributions as related but separate entities and, therefore, exclude them from our exploration below. In what follows, the structure of the sub-chapters aligns with the guiding questions 1 to 3 outlined above, while question 4 will be addressed throughout.

Blackstone

Blackstone is a New York-based private-equity company, known as “the world’s largest alternative asset manager” (Blackstone, 2023, n.d.). Blackstone’s diverse portfolio includes dating platforms, hotels, commercial and residential real estate, and care homes (O’Brien, 2022). Despite managing considerably less assets under management (AUM) in 2022 than BlackRock (8.6 trillion USD) and Vanguard (7.2 trillion USD), Blackstone’s return on AUM is “fifteen times more profitable” (Christophers, 2023, 20), owing to its more active and risk-taking investment strategies. This is emblematic for the post-GFC type of investor, seeking above-average returns in alternative investment classes (ibid). Real estate is a particularly profitable segment for Blackstone (Blackstone, 2023). However, unlike traditional financial products, such as bonds or derivatives, investments in these “alternative assets” directly subject people’s everyday lives to shareholders’ profit-maximising short-termism (Foundational Economy Collective, 2018; Plank et al., 2023)—as is well documented in relation to Blackstone’s housing investments (Birchall, 2019; Burns et al., 2014; Janoschka et al., 2020; Sirota, 2019; Sweeting, 2016).

Key actors

Blackstone is a member of major trade associations, including the American Investment Council, Invest Europe, the Investment Association, and the Managed Funds Association. While information on how these trade associations influence policymaking is scarce, instances are documented. For example, Invest Europe reactively lobbied the European Commission to amend the Solvency II directive. This directive sets solvency capital requirements for insurance companies to reduce financial risks, resulting in lower risk-weightings for equities held by closed-end and unleveraged funds, including Blackstone’s (Debevoise & Plimpton, 2016, 17). Blackstone also employs specialised lobbying firms, including Ogilvy and Mather, whose former employee Wayne Berman now serves as Blackstone’s global head of government relations. His involvement in the campaigns of US Senators Marco Rubio and Mitt Romney, as well as Blackstone’s CEO Steve Schwarzman’s role as external advisor to Donald Trump, illustrate the company’s close ties to policymakers (Arnsdorf and Dawsey, 2017).

The spatiality of lobbying

In the case of housing, Blackstone’s business model exploits local rent gaps by acquiring underperforming properties and selling them after realising their rent potential (Christophers, 2022; Smith, 1979). The effectiveness of this strategy depends on multi-scalar lobbying, which links places, e.g. concrete housing complexes, with territories marked by political rule, e.g. municipal and national regulations or European monetary policies that support house price inflation (Gabor and Kohl, 2022; Ryan-Collins, 2021). For example, in the case of Madrid, successful local lobbying for public divestment enabled Blackstone to cheaply acquire two municipal housing companies (Berwick, 2016; Janoschka et al., 2020, 7). Simultaneously, this strategy profited from proactive lobbying for new national regulations, including tax reliefs for Real Estate Investment Trusts and a liberalised Urban Rental Law (Gil García, Martínez López (2023), 10; Janoschka et al., 2020). It was further facilitated by proactive (Capital Markets Union) and reactive (EU’s Solvency Directives) lobbying on the supranational level (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2018; Gabor and Kohl, 2022).

Resource mobilisation

Financial resources are used for in-house lobbyists and membership fees to trade associations, e.g. to enable Invest Europe to reactively lobby against the EU’s attempt to regulate ‘Alternative Investment Fund Managers’ by shifting the discourse towards enhanced transparency to avoid stricter rules on leveraged buyouts ratios, which are essential for Blackstone’s business model (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2018). Additionally, revolving door practices mobilise human resources: Barcelona’s former mayor Joan Clos is chairman of the Blackstone-backed association of rental property owners (Asval), and Claudio Boada Pallarés, president of one of Blackstone’s largest Spanish subsidiaries (Anticipa), was president of the Círculo de Empresarios, an important business association with official ties to the Spanish government (Gabarre de Sus, 2021). Moreover, contemporary strategic selectivities, marked by reduced capacities of public bureaucracies and the framing of finance as ‘value-creator’ rather than ‘value-taker’ (Mazzucato, 2018), empower financial institutions to mobilise their immaterial resources of knowledge and skills. When the Spanish government established a national bad bank (SAREB) to purchase distressed housing portfolios, Blackstone positioned itself as a competent partner to acquire SAREB’s housing portfolios, possessing not only capital but also skills and knowledge (Janoschka et al., 2020). Accordingly, the Spanish government commissioned Blackstone with the sale of 21,000 apartments from SAREB (Ruiz, 2023), while Blackstone simultaneously denounced plans to include a social housing quota of 30% for corporate private actors in the Urban Rental Law, insisting that social housing is entirely a public responsibility (Aranda, 2021).

BP

BP is a major London-based oil and gas multinational. In 2003, BP launched its “Beyond Petroleum” campaign, and in 2020, it pledged a 40% reduction in oil and gas production. However, amid increasing fossil-fuel prices, BP later revised the reduction to 25%, indicating a shift towards maintaining its fossil development trajectory. In 2022, BP experienced its most profitable year in its 114-year history (Zeller, 2023). After investing significantly in fossil-fuel infrastructure and retracting climate commitments (InfluenceMap, 2023b; Zeller, 2023), BP’s stock outperformed Exxon’s (Jacobs et al., 2023). The illustrative account below focuses on BP’s lobbying efforts to expand LNG production and consumption.

Key actors

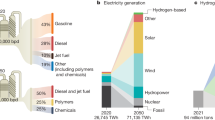

BP lobbies both independently and through its affiliation with 67 trade associations, each requiring annual dues of 50,000 USD or more (BP, 2023). These associations include the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers, FuelsEurope, the US Chamber of Commerce, the European Chemical Industry Council, the US National Association of Manufacturers, and the Federation of German Industries. A 2017 report by InfluenceMap identified the latter four associations as key barriers to ambitious climate policies. Figure 1 shows BP’s significant number of memberships in trade associations actively opposing Paris-aligned climate policies:

Overview of the Supermajor’s industry associations, from InfluenceMap (2022a, 39).

Lobbying firms also wield significant influence, albeit opaquely. For example, Crowne Associates, with BP as a client, provided “administrative support” to a committee of Conservative MPs investigating the UK’s energy crisis (Das, 2022). Despite denying any direct connection, the influential sub-committee proactively recommended relaxed planning laws to facilitate fracking and endorsed new fossil-fuel projects like maximising production in the North Sea basin. Simultaneously, the MPs promoted individual consumer actions such as energy-saving to reduce energy bills.

The spatiality of lobbying

BP’s lobbying activities aim to lock in fossil fuels across the entire value chain, from upstream production to downstream demand. This reinforces infrastructural and technological carbon lock-ins at the level of carbon-emitting infrastructure, carbon emission-supporting infrastructure, and energy-demanding infrastructure (Seto et al., 2016). For example, in the case of LNG, multi-scalar lobbying links different territories (e.g., in the EU and Africa) and places (e.g., gas fields in Mauritania and Senegal with a German living room). In this context, a recent study reveals BP’s simultaneous lobbying and investment activities to expand gas exploration and LNG infrastructure in Mauritania and Senegal on one hand and LNG import infrastructure in Germany on the other (InfluenceMap, 2023). Among others, BP proactively lobbied for accelerated gas supply by pushing the LNG Acceleration Act in Germany through various networksFootnote 2 (Deckwirth, 2023). This Act approved 12 new LNG projects (7 in proposal or construction), exceeding the two recommended by the European Commission and resulting in a risk of prolonged lock-ins as stakeholders seek maximum utilisation (InfluenceMap, 2023b; Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), 2023). A recent study has questioned the need for new LNG projects altogether, given the huge energy-saving potentials in the German building sector (Koch et al., 2022). However, realising these potentials hinges on policies that corporations like BP reactively lobby against such as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, Energy Efficiency Directive, and Hydrogen and Gas Decarbonisation Package (InfluenceMap 2022c, 2023c, 2023d).

Resource mobilisation

Financial resources are crucial, e.g. to enable the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers and FuelsEurope through membership fees to effectively oppose banning fossil fuel-based heating systems and instead advocate for “proportionate”, “more efficient and hybrid solutions”, and consumer choice (FuelsEurope, 2022). Human resources are mobilised through revolving door practices: in 2022, 24 out of 35 BP lobbyists previously held government positions (data for the US; OpenSecrets, 2023b). Furthermore, the securitisation of energy politics in the current conjuncture allows BP to mobilise significant immaterial resources. For example, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU created the Energy Platform Industry Advisory Group to advise on reducing dependence on Russian gas. This group includes fossil-fuel companies like BP but lacks public-interest organisations. Operating under a professional-secrecy clause, it provides regular access for industry representatives to the Commission, particularly targeting the RePowerEU plan and new gas sourcing (Baboulias and Reidy, 2023; see also Corporate Europe Observatory, 2022a). Relatedly, the structural favouring of techno-economic interests—reproduced through climate science and policymaking that subordinate sufficiency to efficiency considerations and public sovereignty to that of consumers and investors (Bärnthaler, 2024b; Stoddard et al., 2021; Hausknost and Haas, 2019)—enables fossil-fuel companies to position themselves as key advisors on securing energy supply in uncertain times (see Cooke, 2022). As such, fossil-fuel companies like BP are not just able to advocate for “technologically neutral” approaches (InfluenceMap, 2022b) but also to frame themselves as key innovators to implement negative-emission technologies to profitably absorb part of their profitably emitted CO2 (see also Brad and Schneider, 2023).

Bayer

The Bayer Group comprises three divisions: pharmaceuticals, consumer health, and crop science, with 354 consolidated companies in 83 countries (Bayer, 2023a). Following its merging with Monsanto in 2018, Bayer became the world’s second-largest pesticide producer (Statista, 2023). Bayer, Syngenta, BASF, and Corteva collectively control two-thirds of the 53-billion-euro pesticide market (Holland and Tansey, 2022), contributing significantly to biodiversity loss (Tang et al., 2021). Additionally, they are closely linked to the pesticide-reliant livestock industry (Ollinaho et al., 2023, 612f). For instance, 77% of soy produced globally is used for feed (Ritchie and Roser, 2021), and 98% of US-based soy fields rely on herbicides (USDA, 2021).

Key actors

Bayer is affiliated with various agribusiness-related trade associations, including Business Europe, the European Chemical Industry Council, Euroseeds, the Pensar Agro Institute, and CropLife Europe, focusing on weakening pesticide regulations (Holland and Tansey, 2022). Bayer also engages in advocacy networks such as the Glyphosate Renewal Group, which proactively lobbied for glyphosate’s approval in the EU (Transparency Register, n.d.) despite its use having prompted lawsuits over cancer cases (Pierson, 2023). Additionally, Bayer employs lobbying firms such as Rud Pedersen Public Affairs, which launched a petition to the German Bundestag to refuse a glyphosate ban without viable alternatives (Rud Pedersen Public Affairs, n.d.). The effectiveness of these actor networks is evident in the European Commission’s approval of glyphosate use for another 10 years, despite the absence of a qualified majority of member states.

The spatiality of lobbying

Similar to the case of BP, Bayer seeks to lock in pesticide use from upstream production to downstream demand. It concentrates its lobbying activities on territories of major im-/exporters of final and value-added food products, e.g. China, the US, and Germany, as well as on those of key suppliers of intermediate products, especially in Latin America and Asia (OECD, 2020, 11; see also Bayer, 2021, 5). This not only links territories (global agricultural trade hubs setting political rules) with places, e.g., agricultural fields where farmworkers are exposed to pesticides, but also depends on multi-scalar lobbying. For example, CropLife operates on a supranational (e.g., CropLife Europe, CropLife International) and national level, where Bayer co-founded CropLife Brazil to influence the Brazilian regulatory system (Ollinaho et al., 2023, 616) as Brazil is the second-largest consumer and the largest importer of pesticides (FAO, 2021; Oliveira et al., 2020; Castilho et al., 2022). CropLife itself collaborates with other industry associations like Europe’s largest farming lobby Copa-Cogeca through networks like the Agri-Food Chain Coalition (AFCC, n.d.). Furthermore, the disclosure of internal government emails shows Bayer and CropLife America’s collaboration with US officials to pressure Mexico into abandoning its proposed ban on glyphosate (Gillam, 2021). This illustrates how inter-territorial power structures favour and are reproduced through Bayer’s lobbying networks.

Resource mobilisation

Bayer mobilises substantial financial resources, ranking among the highest-spending lobbyists in Brussels and devoting a significant share to lobbying agricultural and environmental policies (LobbyFacts, 2023). For example, through its monthly membership fees, the Pensar Agro Institute funds a high-end villa in Brasilia, where Brazilian Congress members hold weekly meetings with member associations (Castilho et al., 2022). Bayer also mobilises human resources through revolving doors, with more than 85% of its US lobbyists having previously worked as governmental employees (OpenSecrets, 2022). Moreover, Bayer holds significant technological and immaterial resources, investing heavily in new GM techniques, productivity-enhancing seeds (Bayer, 2023b), and digital and precision agriculture (Bayer, 2023c), thereby involving Big Tech in food production (Wetzels, 2021; GRAIN, 2021). In a conjuncture favourable to pro-corporate techno-economic strategies, these investments allow Bayer to increase the political dependence on its technologies and knowledge to address issues of food security and climate change, enabling the company to reactively oppose pesticide reduction policies (see also Corporate Europe Observatory, 2021; Holland and Tansey 2022, 8).

Alphabet

Alphabet, a Silicon Valley-based multinational holding company, emerged in 2015 from a Google corporate restructure. Google, Alphabet’s main revenue source, generated 257 billion USD in 2021, accounting for 92% of internet search traffic, 65% of browser usage via Chrome, and a 70% share in the mobile operating system market with Android (Perez, 2020). Since its founding in 1998, Google has diversified beyond its core search-engine business, acquiring companies in high-speed internet (Access), smart-home systems (Nest), cybersecurity (Mandiant), satellite navigation (Waze), AI (Deepmind), Machine Learning (TensorFlow), life sciences (Verily), self-driving technology (Waymo), and urban development (Sidewalk Labs).

Key actors

Alphabet holds various trade-association memberships, including at the Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable, along with affiliations in more than 250 third-party organisations such as the Lisbon Council (a neoliberal think tank advocating self-regulation) and the Centre for Democracy and Technology (Müller, 2020; Google, 2022). This extensive portfolio allows Alphabet to selectively present itself as a progressive and democratic actor despite the contradicting positions among its affiliations (Egan, 2021; Gangitano, 2021). This led investors to complain that Alphabet’s “lobbying contradicts company public positions” (Boston Common Asset Management, 2022). Alphabet works with think tanks, lobbying organisations, and law firms opposing antitrust laws and privacy regulation. Notably, law firms like Clearly Gottlieb and Compass Lexecon have reactively lobbied against regulations such as the EU Digital Markets Act that targets Big Tech monopolies (Bank et al., 2021). None of these firms is registered in the EU’s Transparency Register, highlighting the opacity of Alphabet’s lobbying networks (Müller, 2020).

The spatiality of lobbying

These networks, like those in the financial power complex, aim at “one big market”, global and self-regulated (Polanyi, 2001). To achieve this objective, Alphabet pursues multi-scalar lobbying to disempower the capacity of public regulators, while striving to maintain full control over data management for predictions, commercialisation, and sale (see, e.g., Corporate Europe Observatory, 2023; Mehrotra et al., 2019; Bank et al., 2021; Silva, 2021; LobbyControl, 2020). This multi-scalar strategy links different territories of political rule, from municipalities to the EU, with places, e.g., concrete neighbourhoods. The case of Alphabet’s subsidiary Sidewalk Labs’ Toronto Quayside project offers an emblematic example. Using over 100 lobbyists, Alphabet lobbied city officials and politicians to circumvent established and democratically legitimised urban planning frameworks (Kudva et al., 2023; Filion et al., 2023; Florida and Beddoes, 2019). Among others, these lobbying efforts aimed at emphasising the benefits of affordable housing and job creation while masking issues of privacy and data management (Appiah, 2022; Wylie, 2019). The project aimed to integrate data extraction technologies into the physical infrastructure of the entire neighbourhood, enabling targeted advertising through movement tracking (Cooke, 2020). However, facing opposition from place-based civil-society initiatives (e.g., BlockSidewalk) and demands from territorial policymakers to comply with privacy regulations, Alphabet abandoned the project, citing escalating costs during the Covid-19 pandemic (Doctoroff, 2020).

Resource mobilisation

Alphabet was the third-largest spender on EU lobbying in 2022 (Corporate Europe Observatory, 2022b). Despite these substantial lobbying expenditures, the company presents itself as a neutral mediator and cosmopolitan actor, who safeguards global markets as well as privacy and data security from state surveillance (Popiel, 2018; Planqué-van Hardeveld, 2023). While Alphabet’s lobbying is largely reactive to new regulations—often advocating for self-regulation as economically preferable (Popiel, 2018, 576; Coroado, 2023)—this progressive framing is used as an immaterial resource to justify its proactive lobbying to limit public access to corporate data (Popiel, 2018). In the US alone, Alphabet employed 96 federal lobbyists in 2022, 82% of whom had previously worked in the public sector (OpenSecrets, 2023a). These revolving door strategies are facilitated by post-administrative state rationales and techno-economic policymaking, amplifying the dependence of public institutions on tech companies for governance tasks and cloud service stability (Coroado, 2023; Withers and Jones, 2021). It has enabled Alphabet to expand its control over critical physical infrastructures, investing in submarine cables globally, in broadband infrastructure in Africa, and in public Wi-Fi hotspots across Asia (Sawers, 2019). This de facto monopolisation of critical resources, including infrastructures and knowledge, positions tech giants like Alphabet as “too big to fail” (Kak and Myers West, 2023), while weaving their digital services into ever more aspects of everyday life.

Conclusion: implications and challenges for realising a wellbeing economy

Drawing on different strands of existing scholarship, this article outlined an analytical framework for understanding the political and economic barriers to achieving a wellbeing economy, thereby addressing a gap in wellbeing-economy research. It highlights how agential and structural power are distinct but entwined: while actor-coalitions have the power to shape structures (provided they reflect on the structural context and have the necessary resources), structures not only pre-exist human agency but are also strategically selective, favouring some actors, interests, and strategies over others. To make sense of this interplay between agential and structural power, we introduced the concept of a power complex—a time-space-specific actor-coalition with common industry-related interests that has the power to reproduce or transform structures.

Against this backdrop, we posed four research questions. First, to better understand the historical “becoming” of today’s political-economic terrain, we asked how certain power complexes have emerged through time-space-specific power structures. Taking a regulationist-inspired approach, we traced the co-evolution of specific modes of regulation (colonial-liberal, Fordist, neoliberal) and power complexes (financial, fossil, livestock-agribusiness, and digital). On one hand, certain modes of regulation favour certain actors, interests, and strategies, as seen in the temporary decline of the financial power complex during Fordism. On the other hand, power complexes have agential power to shape modes of regulation, resulting in specific accumulation regimes, as seen in the return of the financial power complex during neoliberalism. Over the last decades, all four power complexes have interacted in favouring neoliberal globalisation that introduced a new scale of extraction—of materials, rents, and data. This threatens key pillars of a wellbeing economy, such as ecological sustainability, equ(al)ity, and democracy.

Second, exploring today’s structural context, defined as an interregnum, we investigated the composition of contemporary power complexes, emphasising the increased power of multi- and transnational corporations. We highlighted strategic selectivities with respect to the technical complexity and multi-scalarity of policy processes, structural barriers for civil-society actors and transformative climate science to access spaces of influence, high capital mobility, and post-administrative states. These selectivities favour economic over political actors, multi- and transnational corporations over civil society, labour movements, and public bureaucracies. Today, struggles for a wellbeing economy have to acknowledge that corporate actors have become strongly anchored in state institutions at multiple levels, exhibiting significant control over relevant state apparatuses and processes. Without limiting this power, political strategies are unlikely to actualise.

This led to our third research questionon corporate actors’ key strategies to exercise power in this conjuncture, focusing on one such strategy: firm-to-state lobbying. Here, we selectively drew upon specific cases—Blackstone (financial), BP (fossil), Bayer (livestock-agribusiness), and Alphabet (digital)—to illustrate key pillars of an analytical heuristic for studying firm-to-state lobbying as a socio-spatial strategy that mobilises diverse resources to influence policies and shape regulations. This framework integrates key actors involved in firm-to-state lobbying, its spatiality, and the resources mobilised.

Exploring the three research questions above offered insights for answering the fourth regarding the challenges in realising a wellbeing economy based on post-/degrowth visions. It indicated that associated actor-coalitions face a wicked conjuncture in terms of possible and necessary alliances, the spatiality of strategic action, and the form of transformative agency. On one hand, they have to confront large corporations as well as the self-expanding and extractive logic of capitalism, which underpin social-ecological crises (Pirgmaier and Steinberger, 2019; Hickel, 2021; Bellamy Foster, 2023). Hence, realising a wellbeing economy requires the agential power to limit the structural power of capital for undirected accumulation. On the other hand, agential power is always actualised in the given politico-economic structures, which favour strategies of capital accumulation as well as corporate actors able to operate at multiple levels. Drawing on insights from the historical analysis and the analysis of secondary sources on instances of firm-to-state lobbying, we conclude by outlining three key challenges for destabilising and altering power complexes in favour of a post-/degrowth-oriented wellbeing economy.

Building unconventional actor-coalitions

Every mode of regulation depends on certain non-capitalist institutions, be it unpaid caring or decommodified welfare-state services. While these preconditions are part and parcel of capitalism (Fraser, 2014), they have their own institutional logic as they are essential for satisfying human needs (Bärnthaler et al., 2021; Bärnthaler and Gough, 2023). Strengthening these foundations not only entails potentials for broad alliances (Foundational Economy Collective 2018; Coote and Percy 2020; Bärnthaler et al. 2023, Bärnthaler 2024a) but is potentially anti-capitalist if it challenges capitalism’s subordination of social reproduction to capitalist production (Bärnthaler and Dengler, 2023). This resonates with existing degrowth scholarship, which highlights emancipatory forms of decommodification of foundational goods and services (Dengler and Lang, 2022; Kallis et al., 2020; Hickel, 2021). However, given the dominance of capitalist structures, such an endeavour will need to resonate with some capital fractions, e.g., patient capital, socially licensed capital, and capital involved in supplying decarbonised essential provisioning systems (see also Newell, 2019; Overbeek, 2013). Therefore, against the backdrop of contemporary strategic selectivities, a key challenge resides in building alliances that include not only “working-class constituents” (Kallis et al., 2020, 107) but, in the short and medium term, also certain capital fractions (making associated strategies more likely to be selected and retained), without losing sight of the long-term post-capitalist horizon. Such a strategy is Realpolitik with revolutionary potential (Luxemburg, 2006), nourishing the breeding ground for struggles for transformative change, e.g., by reducing inequality, creating material security, and shifting productive capacities to what is essential for wellbeing (Hickel et al., 2022; Vogel et al., 2024; Vogel et al. 2021). Whereas degrowth strategising acknowledges the need for such a dialectical approach—often referring to Luxemburg’s revolutionary Realpolitik, Gorz’ non-reformist reforms, or Bloch’s concrete utopias (see, e.g., Dengler et al. 2022, Schmelzer et al., 2022)—the strategically decisive role of certain capital fractions in the current conjuncture has remained systematically underexposed.

Operating on all spatial dimensions simultaneously

The illustrative cases highlight that successful firm-to-state lobbying operates on and links different spatial dimensions, like territories, places, scales, and networks. Therefore, strategies for realising a wellbeing economy must take this diversity into account: successful firm-to-state lobbying has never limited itself to local, place-based action without proactively supporting multi-scalar networking and engaging with multi-level territorial decision-making, be it in municipalities, sovereign nation-states or global institutions. This poses a particular challenge for degrowth strategising when networking remains communal, local, and place-based (e.g., Cattaneo, 2014; Trainer, 2020), when a bias towards interstitial action prevents engaging with dominant multi-level institutions, and when local and global dimensions (“glocalisation”) are prioritised over national territories. Thus, operating on all spatial dimensions simultaneously is a key challenge for actor-coalitions seeking to realise a wellbeing economy. Historical analyses show that selective economic deglobalization, especially capital controls and other restrictions on locational competition, are a prerequisite for empowering such multi-level political spaces of manoeuvre (Rodrik, 2012; Novy, 2022).

Institutionalising alternative ways to mobilise (alternative) resources to shape regulation

It is one thing to control certain resources but another to be able to mobilise them to influence policymaking. Today’s significance of firm-to-state lobbying is both an outcome of structures that favour corporate actors and a practice that reproduces these structural selectivities. Thus, a decisive challenge for realising a wellbeing economy resides in building and strengthening democratic political spaces on multiple levels (from the workplace and neighbourhood to the nation-state and the EU) to enable alternative actors to effectively mobilise alternative resources (e.g., beyond techno-economic knowledge) to shape regulation. Such democratisation is a key pillar of enabling strategic agency in degrowth scholarship (see Hausknost, 2017). At the same time, strengthening participatory and deliberative democratic institutions must be accompanied by strategies to secure positions within the state apparatus (Poulantzas, 1978; Bärnthaler, 2024a) to translate associated outcomes into general rules, laws, and funding schemes, e.g., to support decommodified forms of provisioning. While many degrowth scholars have highlighted the crucial role of a state agency (Cosme et al., 2017; D’Alisa and Kallis, 2020; Koch, 2022), degrowth practice has remained strongly based on bottom-up action, with little consideration on how to occupy strategic positions in the state and public bureaucracies. However, consciously combining bottom-up with top-down agency is a precondition to transform structures towards a post-/degrowth-oriented wellbeing economy.

Data availability

The research is based on secondary data, all relevant references have been provided in the article.

Notes

While losses from stranded fossil assets would not significantly affect most wage earners, affluent fossil-fuel interests prioritise protecting their wealth (Semieniuk et al., 2023).

BP holds memberships in major German trade associations that actively lobby for accelerated gas supply such as the Bundesverband der Energie- und Wasserwirtschaft (which is itself member of the influential gas lobby coalition Zukunft Gas). BP is also a sponsoring member of the German Green party-affiliated association “Grüner Wirtschaftsdialog”, which links business and politics (Deckwirth, 2023; LobbyControl, 2020).

References

Achakulwisut P, Lazarus M, Asvanon R, Almeida PC, Fauzi D, Ghosh E, Nazareth A, Araújo JAV (2023) The Production Gap Report 2023: Phasing down or phasing up? Top fossil fuel producers plan even more extraction despite climate promises. https://doi.org/10.51414/sei2023.050

AFCC (n.d.) Member Associations. Retrieved 8 November 2023, from https://agrifoodchaincoalition.eu/members/

Aglietta M (1998) Capitalism at the turn of the century: regulation theory and the challenge of social change. N. Left Rev. I/232:41–90

Almiron N, Rodrigo-Alsina M, Moreno JA (2022) Manufacturing ignorance: think tanks, climate change and the animal-based diet. Environ. Polit. 31(4):576–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2021.1933842

Almiron N, Xifra J (2021) Climate Change Denial and Public Relations: Strategic Communication and Interest Groups in Climate Inaction. Routledge

Anderson K (2015) Duality in climate science. Nat. Geosci., 8(12), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2559

Appiah E (2022, November 2) Company Profile: Sidewalk Labs—The Tech Lobby. https://thetechlobby.ca/company-profile-sidewalk-labs/

Aranda JL (2021) Blackstone recuerda a Podemos que el alquiler social “es responsabilidad de las Administraciones Públicas”. El País. https://elpais.com/economia/2021-02-02/blackstone-recuerda-a-podemos-que-el-alquiler-social-es-responsabilidad-de-las-administraciones-publicas.html

Arnsdorf I, Dawsey J (2017) Trump’s billionaire adviser stands to gain from policies he helped shape. POLITICO. https://www.politico.com/story/2017/04/trump-schwarzman-blackstone-influence-237341

Arrighi G (1994) The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Power, and the Origins of Our Times. Verso

Atal MR (2020) The janus faces of silicon valley. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 28(2):336–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2020.1830830

Avelino F, Rotmans J (2009) Power in transition: an interdisciplinary framework to study power in relation to structural change. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 12(4):543–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431009349830

Baboulias Y, Reidy P (2023) The Gas Lobby’s Boiler Battle. European Environmental Bureau. https://eeb.org/library/the-gas-lobbys-boiler-battle/

Ban C, Bohle D, Naczyk M (2022) A perfect storm: COVID-19 and the reorganisation of the German meat industry. Transf.: Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 28(1):101–118. https://doi.org/10.1177/10242589221081943

Bank M, Duffy F, Leyendecker V, Silva M (2021) Big Tech’s Web of Influence in the EU. LobbyControl. https://corporateeurope.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/The%20lobby%20network%20-%20Big%20Tech%27s%20web%20of%20influence%20in%20the%20EU.pdf

Barns S (2019) Negotiating the platform pivot: From participatory digital ecosystems to infrastructures of everyday life. Geogr. Compass 13(9):e12464. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12464

Barns S (2020) Platform Urbanism: Negotiating Platform Ecosystems in Connected Cities. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-32-9725-8

Bärnthaler R (2024a) Towards eco-social politics: a case study of transformative strategies to overcome forms-of-life crises. Environ. Polit. 33(1):92–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2023.2180910

Bärnthaler R (2024b) When enough is enough: Introducing sufficiency corridors to put techno-economism in its place. Ambio. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-024-02027-2

Bärnthaler R, Dengler C (2023) Universal basic income, services, or time politics? A critical realist analysis of (potentially) transformative responses to the care crisis. J. Crit. Realism 22(4):670–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767430.2023.2229179

Bärnthaler R, Gough I (2023) Provisioning for sufficiency: envisaging production corridors. Sustainability 19(1):2218690. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2023.2218690

Bärnthaler R, Novy A, Plank L (2021) The foundational economy as a cornerstone for a social–ecological transformation. Sustainability 13(18):10460. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810460

Bärnthaler R, Novy A, Stadelmann B (2023) A Polanyi-inspired perspective on social-ecological transformations of cities. J. Urban Aff. 45(2):117–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2020.1834404

Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R (2018) The biomass distribution on Earth. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115(25):6506–6511. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1711842115

Bayer (2021) Industry Association Climate Review. https://www.bayer.com/sites/default/files/Bayer%20Industry%20Association%20Climate%20Review%202021_0.pdf

Bayer (2023a) Names, Facts, Figures about Bayer. Names, Facts, Figures about Bayer |. https://www.bayer.com/en/strategy/profile-and-organization

Bayer (2023b) Seeds and Traits. https://www.bayer.com/en/agriculture/seeds-traits

Bayer (2023c, July 10) Digital Farming. https://www.bayer.com/en/agriculture/digital-farming

Bayliss K, Gideon J (2020) The privatisation and financialisation of social care in the UK (No. 238; SOAS Department of Economics Working Paper Series). SOAS University of London

Becker J (2002) Akkumulation, Regulation, Territorium: Zur kritischen Rekonstruktion der französischen Regulationstheorie. Metropolis

Becker J, Novy A (1999) Divergence and convergence of national and local regulation: the case of Austria and Vienna. Eur. Urb. Reg. Stud. 6(2):127–143. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649900600203

Bellamy Foster J (2023) Planned degrowth: ecosocialism and sustainable human development. Mon. Rev. 75(3):1–29

Benbrook, CM (2012) Impacts of genetically engineered crops on pesticide use in the U.S. – the first sixteen years. Environmenta Sciences Europe, 24(24). https://doi.org/10.1186/2190-4715-24-24

Berman M (2010) All That Is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity. Verso Books

Berwick A (2016) Spanish social housing sale to Blackstone was flawed, auditors find. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-spain-evictions-idINKCN0X32DJ

Bhaskar R (1998) Societies. In T. Lawson, A. Collier, R. Bhaskar, M. Archer, A. Norrie (Eds.), Critical Realism: Essential Readings (pp. 206–257). Routledge

Birchall D (2019) Human rights on the altar of the market: the Blackstone letters and the financialisation of housing. Transnatl. Leg. Theory 10(3–4):446–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/20414005.2019.1692288

Blackstone (n.d.) Our People. Retrieved 9 November 2023, from https://www.blackstone.com/people/wayne-berman/

Blackstone (2023) Blackstone Announces $30.4 Billion Final Close for Largest Real Estate Drawdown Fund Ever. https://www.blackstone.com/news/press/blackstone-announces-30-4-billion-final-close-for-largest-real-estate-drawdown-fund-ever/

Bonneuil C, Fressoz J-B (2017) The Shock of the Anthropocene: The Earth, History and Us (D. Fernbach, Trans.). Verso Books

Boston Common Asset Management (2022) Boston Common Asset Management seeks your support for Proposal 5 on the Company’s 2022 Proxy Statement. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1409427/000121465922007183/p518221px14a6g.htm

Boyer R, Saillard Y (2010) Théorie de la régulation, l’état des savoirs. La Découverte

Brad A, Schneider E (2023) Carbon dioxide removal and mitigation deterrence in EU climate policy: towards a research approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 150:103591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2023.103591

Braun B (2016) Speaking to the people? Money, trust, and central bank legitimacy in the age of quantitative easing. Rev. Int. Political Econ. 23(6):1064–1092. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2016.1252415

Braun B (2021) Asset Manager Capitalism as a Corporate Governance Regime. In J. S. Hacker, A. Hertel-Fernandez, P. Pierson, K. Thelen (Eds.), The American Political Economy (1st ed., pp. 270–294). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009029841.010

Braun B, Koddenbrock K (2022) Capital Claims: Power and Global Finance (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003218487

BP (2023) Our participation in trade associations: 2023 progress update. BP. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/sustainability/our-participation-in-trade-associations-2023-progress-update.pdf

Brulle R, Downie C (2022) Following the money: trade associations, political activity and climate change. Clim. Change 175(3):11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-022-03466-0

Brulle RJ (2018) The climate lobby: a sectoral analysis of lobbying spending on climate change in the USA, 2000 to 2016. Clim.Change 149(3):289–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-018-2241-z

Brulle RJ (2020) Denialism: Organized opposition to climate change action in the United States. In D. Koninsky (Ed.), Handbook of Environmental Policy (pp. 328–341). Edward Elgar

Brulle RJ, Werthman C (2021) The role of public relations firms in climate change politics. Clim. Change 169(1–2):8

Büchs M, Baltruszewicz M, Bohnenberger K, Busch J, Dyke J, Elf P, Fanning A, Fritz M, Garvey A, Hardt L (2020) Wellbeing Economics for the COVID-19 recovery: Ten principles to build back better (Ht tps://Weall.Org/Wp-Content/Uploads/2020/05/Wellbeing_Economics_for_the_COVID-19_recovery_10Principles. Pdf). Wellbeing Economy Alliance. https://weall.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Wellbeing_Economics_for_the_COVID-19_recovery_10Principles.pdf

Bukold S (2023) The Dirty Dozen—The Climate Greenwashing of 12 European Oil Companies. Greenpeace. https://www.energycomment.de/new-report-the-dirty-dozen/

Burns R, Donley M, Manzanet C (2014) Game of Homes. In These Times. https://inthesetimes.com/article/game-of-homes

Cadwalladr C, Graham-Harrison E (2018, March 17) Revealed: 50 million Facebook profiles harvested for Cambridge Analytica in major data breach. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/mar/17/cambridge-analytica-facebook-influence-us-election

Cann V (2022, July 28) Exploiting the Ukraine crisis for Big Business. Corporate Europe Observatory. https://corporateeurope.org/en/2022/07/exploiting-ukraine-crisis-big-business

Castilho AL, de Freitas Paes C, Linder L, Fuhrmann L, Ramos MF (2022) The Financiers of Destruction: How Multinational Companies Sponsor Agribusiness Lobby and Sustain the Dismantling of Socio-Environmental Regulation in Brazil. De Olho nos Ruralistas. https://deolhonosruralistas.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Financiers-of-Destruction-2022-EN.pdf

Cattaneo C (2014). Eco-communities. In G. D’Alisa, F. Demaria, G. Kallis (Eds.) Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era (pp. 165–168). Routledge

Chafkin M (2022) Contrarian. Bloomsbury Publishing

Christophers B (2022) Mind the rent gap: blackstone, housing investment and the reordering of urban rent surfaces. Urban Stud. 59(4):698–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211026466

Christophers B (2023) Our lives in their portfolios: Why asset managers own the world. Verso

Cooke P (2020) Silicon valley imperialists create new model villages as smart cities in their own image. J. Open Innov. 6(2):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6020024

Cooke P (2022, December 7) A new era for Germany’s gas industry fuels climate fears. DeSmog. https://www.desmog.com/2022/12/06/a-new-era-for-germanys-gas-industry-fuels-climate-fears/

Cooke P (2023, July 20) Revealed: media blitz against heat pumps funded by gas lobby group. DeSmog. https://www.desmog.com/2023/07/20/revealed-media-blitz-against-heat-pumps-funded-by-gas-lobby-group/

Coote A, Percy A (2020) The Case for Universal Basic Services (1. Edition). Polity

Coroado S (2023) Leviathan vs Goliath or States vs Big Tech and what the digital services act can do about it. Working Papers, Forum Transregionale Studien, vol. 25/2023. https://doi.org/10.25360/01-2023-00038

Corporate Europe Observatory (2018) How the financial lobby won the battle in Brussels. https://corporateeurope.org/en/financial-lobby/2018/09/how-financial-lobby-won-battle-brussels