Abstract

Meyer’s minority stress model posits that sexual minority communities can act as protective factors for individuals within the sexual minority. Given that existing evidence on this proposition is inconclusive, a social network approach was employed to capture diversity in the social environment of individuals involved in chemsex that might account for variations in social resources and sexual health. This study examined the social networks of men who have sex with men (MSM) involved in sexualised drug use, using data from a cross-sectional online survey. Utilising cluster analysis, four distinct social network types were identified based on network composition: MSM-diverse, partner-focused, family-diverse, and chemsex-restricted. In terms of social resources, the four network types did not exhibit significant differences in social support. However, individuals with a chemsex-restricted social network reported stronger social influence related to chemsex and less social engagement outside of chemsex. Contrary to initial expectations, the four network types did not differ in chemsex-related consequences or sexual satisfaction. MSM engaged in chemsex for over 5 years reported more chemsex-related consequences and lower sexual satisfaction, particularly those with a family-diverse social network. Additionally, indicators of network quality, such as perceived emotional closeness, reciprocity with network members, and overall satisfaction with the network, were more influential in predicting sexual health outcomes than social resources. The findings of the study suggest that the social environment of MSM engaged in chemsex plays a role in shaping their experiences. Insufficient inclusion in a sexual minority community is potentially associated with an elevated risk of poor sexual health. These findings underscore the importance of tailoring interventions to address the diverse needs of individuals exposed to different social environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chemsex is a social phenomenon defined as sex between men under the influence of psychoactive substances taken shortly before or during sexual encounters (Bourne et al., 2014). Thus, chemsex constitutes a unique kind of sexualised substance use by men who have sex with men (MSM) that differs from other forms of intoxicated behaviour in terms of the main substances involved, the context and setting of consumption, as well as (sub-)cultural factors contributing to its emergence (Maxwell et al., 2019; Stuart, 2019). The phenomenon has received significant attention in scientific research, media, and popular culture in recent years (Stuart, 2019). The public discourse surrounding the use of drugs in sexual contexts by MSM has predominantly focused on the associated risks and negative outcomes (Jaspal, 2022; Møller and Hakim, 2021). Consequently, empirical investigations have provided substantial evidence for a multitude of associated consequences on a physical, social, and mental level (Bohn et al., 2020; Glynn et al., 2018; Hammoud et al., 2018; Hegazi et al., 2017; Hibbert et al., 2019; Moody et al., 2018; Pakianathan et al., 2018). Theoretical frameworks such as the minority stress model and syndemic theory have been deliberated frequently in the context of chemsex (Íncera-Fernández et al., 2021; Pollard et al., 2018). These frameworks have been instrumental in elucidating factors contributing to health disparities faced by sexual minorities compared to cis-gender heterosexuals (Meyer, 2003; Singer et al., 2006). However, in addition to identifying risk factors, these models also conceptualise protective factors, including community resources and social support. These can be beneficial for sexual minority individuals through their affiliation with a broader sexual minority community (Meyer, 2015; Stall et al., 2007).

Nevertheless, previous research yielded conflicting results regarding the role of sexual minority communities in promoting health. While in some instances greater affiliation or identification with the community was related to better mental and sexual health outcomes (Hotton et al., 2018; Kertzner et al., 2009; Petruzzella et al., 2019; Salfas et al., 2019), other authors found negative effects like heightened substance use involvement and sexual risk-taking (Demant et al., 2018; Hotton et al., 2018).

Inconsistencies of this kind may be due to conceptual issues related to the implicit assumption of the gay community as a single entity to which all MSM belong. By defining a priori who or what constitutes the community based on predetermined criteria, such as a specific sexual minority status, researchers limit diversity in the social environment of sexual minority individuals. However, the social environment can vary notably in terms of their composition, the social resources they offer, and their impact on health (Barrett and Pollack, 2005; Holt, 2011; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2013; McLaren et al., 2008).

Therefore, it seems valuable to identify different social networks of MSM engaging in chemsex, in order to account for the potential heterogeneity in their social environments and the associated effects. In this regard, the concept of homophily posits that individuals tend to form relationships with others who are similar to them in terms of sociodemographic factors, behaviour, and characteristics (Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954; McPherson et al., 2001). Consequently, homophily in social connections may limit the range of information, norms, attitudes, and activities to which an individual is exposed.

This notion is supported by empirical evidence of the broader social network literature, indicating that individuals in the general population with diverse social networks (i.e. not limited to similar others) exhibit better mental and social health outcomes (Cheng et al., 2009; Fiori et al., 2006). Consistent with this finding, homophily in sexual minority networks has been linked to outcomes related to chemsex. For instance, social networks predominantly consisting of other MSM show higher odds of engaging in unprotected sexual intercourse and substance use (Carpiano et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2008). Additionally, the compositional aspects of social networks among sexual minority individuals, such as the proportion of family members, steady partners, friends, or other sexual minority individuals, have differential moderating effects on outcomes related to chemsex. For example, a higher proportion of friends amplifies the effect of group sex on HIV infection, while a higher proportion of family members buffers the effect of involvement in the justice system on HIV infection (Teixeira da Silva et al., 2020). Furthermore, variations in network composition are linked to the social resources conceptualised within the minority stress framework as well (Meyer, 2015). Specifically, for sexual minority individuals, the effects of social support provided by family members, sexual minority friends, or non-sexual minority friends differ depending on whether support is related to their sexual identity. For example, in cases of sexuality-related issues support from fellow sexual minority individuals might be more beneficial while in other occasions support from a family member might have a more useful impact (Doty et al., 2010; Masini and Barrett, 2008; Sattler et al., 2016).

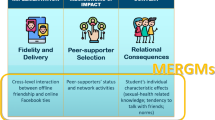

The aim of the present study was to characterise different types of social networks among MSM engaged in chemsex, distinguishing between those limited to fellow chemsex users and those with a more diverse composition (Research question 1). Furthermore, we anticipated that social networks primarily comprising non-chemsex users would offer restricted social resources in terms of social support, social norms, and social engagement (Hypothesis 1). Additionally, we assumed that individuals within these networks would exhibit less favourable sexual health outcomes, including more chemsex-related consequences associated with their sexualised substance use and lower sexual satisfaction (Hypothesis 2). We also assessed participants’ duration of engagement in chemsex, assuming that those involved in a social environment characterised by constrained health-promoting norms and behaviours for an extended period of time would be particularly at risk for experiencing more negative and less positive outcomes (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we included measures of perceived network quality because they have been shown to be highly predictive of the ability to maintain health and account for a substantial proportion of the variance in health outcomes (Antonucci et al., 2014; Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010; Laireiter, 1993). Therefore, in an explanatory investigation, we aimed to examine the impact of all three social resource variables (social support, social influence, and social involvement) as well as all three network quality variables (perceived emotional closeness, perceived reciprocity, and network satisfaction) on predicting sexual health outcomes such as chemsex-related consequences and sexual satisfaction (Research question 2).

Materials

Participants and procedures

Data for the present study were collected through an online cross-sectional survey (see supplementary materials for all instruments and items included in the questionnaire), which was disseminated through a network of practitioners and (LGBTIQ-)organisations working in the field in Berlin, on social media platforms, and websites. Additionally, a respondent-driven sampling approach was employed, utilising a QR code that participants could share with individuals known to be engaged in chemsex. Prior to participation, all subjects provided informed consent and confirmed their age to be over 18 (the study’s preregistration is available at https://aspredicted.org, #40934).

To be eligible for the study, participants were required to self-identify as cis-male or trans*-male and report past or current sexual activity with men. Additionally, we collected data on sexual orientation for descriptive purposes, assessing attraction towards individuals of different gender identities (i.e. towards women; towards men; towards men and women; towards women and gender-neutral people; towards men and gender-neutral people; towards men, women and gender-neutral people; I am not attracted to anyone). However, individuals were included based on self-reported sexual behaviour rather than sexual attraction to ensure inclusion of MSM regardless of their self-identified sexual orientation. Furthermore, participants had to report the intentional use of psychoactive substances during sexual encounters with men. We used a broad definition of chemsex that encompassed a range of substancesFootnote 1, reflecting the substantial prevalence of the sexualised consumption of these substances documented in prior research with German MSM samples (Bohn et al., 2020; Deimel et al., 2016). Thus, individuals who reported the use of GHB/GBL, mephedrone, methamphetamine, ecstasy/MDMA, ketamine, amphetamine and cocaine in sexualised settings were included.

A total of 241 participants completed the survey. However, twelve participants were excluded from data analysis as they did not report engaging in sexual activity under the influence of drugs, and an additional 24 participants were excluded for not reporting the use of any of the relevant substances. Furthermore, the data of three individuals were eliminated from analysis as they did not report any individuals as part of their social network. Consequently, the final sample comprised 202 participants.

Independent measures

Social network structure

Following methods employed in previous research (Frost et al., 2016; Teixeira da Silva et al., 2020), participants were instructed to nominate up to seven individuals with whom they have frequent contact. To ascertain the composition of their social networks, participants were required to categorise each nominated person as a family member, steady partner, MSM friend, non-MSM friend, co-worker/fellow student, or “other”. Additionally, participants were asked to indicate whether each network member was involved in chemsex, allowing us to differentiate chemsex-MSM from non-chemsex-MSM within each network. This approach yielded variables for network size and the relative proportion of individuals in each category, calculated by dividing the absolute number of individuals in each category by network size. These variables were utilised to derive distinct social network types.

Duration of engagement in chemsex

We assessed the number of years that participants have been practising chemsex on a 6-point ordinal scale (from “less than 1 year” to “more than 5 years”). We then compared this effect on the main dependent measures with the results of the social network structures as described above.

Social network resources

Social support

We assessed social support by modifying items from the Social Support Questionnaire (Fydrich et al., 2009). Following the procedure of Frost and colleagues (2016), the items were adjusted to suit the format of the network survey. For each item, participants were asked to identify individuals from their nominated network whom they perceived could provide the specific kind of support. The scale comprised eight items, with four assessing emotional support and four focusing on different types of instrumental support (α = 0.937). We computed a sum score by summing the number of potential support providers across all types of support. Given variations in the number of network individuals nominated by respondents, we standardised the sum score by dividing it by network size to derive an average value for potential overall social support provided by the network. In order to ascertain the alignment of social network types with potential sources of social support, we aggregated the social support scores for each type of provider (i.e. family member, a steady partner, chemsex-MSM, non-chemsex-MSM, non-MSM friend, co-worker/fellow student). Subsequently, we divided the sums by the absolute number of each type of provider within a respective network, thereby reflecting the average perceived social support from each provider category. Given that the social support scale comprised eight items, the range of average overall social support and the resulting six average scores for provider-specific social support ranged from 0 to 8.

Social influence

We operationalised social influence as the perception of descriptive and injunctive norms (Cialdini and Trost, 1998) regarding substance use, sexual risk-taking, and substance use in sexual settings. Therefore, we adapted items from the network analysis approach of Barman-Adhikari and colleagues (2017, 2018) for the purpose of the current study. Items assessing descriptive norms enquired about respondents’ perceptions of the prevalence of specific substance use or sexual behaviour within their network. Injunctive norms, on the other hand, were assessed by asking about the level of disapproval within the network for the respective behaviour. We evaluated social norms for four different types of behaviour, resulting in eight items (α = 0.859). Response options ranged from “none” to “all” on a 5-point scale. We reverse coded injunctive norm responses (i.e. higher scores indicating stronger approving social influence regarding substance use, sexual risk-taking, and substance use in sexual contexts).

Social engagement

Social engagement was operationalised as social participation in a variety of different activities. Therefore, similar to the social participation subscale of Hanson and colleagues (1997), we provided a list with 14 different activities. Participants were asked to choose which activities they had done with individuals from their social network within the last twelve months prior to data collection.

Social network quality

Perceived emotional closeness

To assess perceived emotional closeness in the relationship to each network person, we used the Inclusion of Other in the Self Scale (IOSS; Aron et al., 1992). This graphic instrument employs five images depicting two overlapping circles to represent varying degrees of perceived closeness in relationships. Participants were instructed to select the image that best reflected their perception of closeness for each nominated network person. Subsequently, a mean value for all reported relationships was calculated. As each scale item referred to a different network individual, the scale consisted of up to seven subscales, making it impractical to calculate internal consistency.

Perceived reciprocity

We used the Graphic Balance Scale (GBS; Neyer et al., 2011) to measure perceived reciprocity. Similar to the IOSS, the GBS consists of five graphic items that depict balances with varying tilt to represent varying reciprocity. For each network individual nominated, participants had to select the image that reflects their perception of reciprocity in that respective relationship in terms of help, favours, emotional support, and so on. We then recoded the values to reflect a unidimensional variable (1 = non-reciprocal, 2 = more or less reciprocal, 3 = reciprocal) and calculated an average over all network individuals reported.

Satisfaction with network

Finally, participants were asked how satisfied they are with their social network by using the satisfaction subscale of the Social Support Questionnaire (Fydrich et al., 2007). The subscale consisted of five items assessing the degree of satisfaction with different kinds of resources provided by the network on a 5-point Likert-scale (α = 0.800). Three items were recoded so that higher scores represent more satisfaction.

Indicators of sexual health

Chemsex-related consequences

Since there is no chemsex-specific scale available to assess negative consequences of combining illicit substances and sex, we constructed a questionnaire ourselves. We combined items from the Short Inventory of Drinking Problems—Modified for Drug Use (SIP-DU; Allensworth-Davies et al., 2012) and the Hypersexual Behaviour Consequences Scale (HBCS; Reid et al., 2012) and adapted them to the context of chemsex. We augmented the scale by including adverse consequences of chemsex commonly reported in previous research (Deimel et al., 2016; Dichtl et al., 2016). The scale comprised 25 items assessing the relative frequency of experiencing each issue on a 5-point scale. Due to highly right-skewed distributions, we recoded responses into a dichotomous format, akin to the original SIP-DU’s assessment of lifetime consequences (Allensworth-Davies et al., 2012). Specifically, “never” was recoded as 0 (no experience of consequence), while all other options were recoded as 1 (consequences experienced). Subsequently, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis with Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure (KMO = 0.95) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (χ2 (300) = 2208.6, p < 0.001) indicating adequate sampling and suitability for factor analysis across all 25 itemsFootnote 2. Next, we performed a PCA based on polychoric correlations for binary variables. Both the resulting eigenvalues and scree-plot indicated to extract only one factor onto which all items loaded sufficiently high (range: 0.489–0.871; α = 0.924). Factor analyses were performed by using the software FACTOR (Version 10.10.03) (Lorenzo-Seva and Ferrando, 2006).

Sexual satisfaction

As one potential positive outcome of chemsex, we assessed sexual satisfaction with the Satisfaction with Sex Life Scale (SWSLS; Neto, 2012). The SWSLS consists of five items assessing sexual satisfaction on a 5-point Likert-scale (α = 0.906).

Statistical methods

In order to answer research question 1, we conducted a cluster analysis to derive social network types with unique structural characteristics, following the approach adopted in prior research (Cheng et al., 2009; Fiori et al., 2006; Litwin and Landau, 2000). Given the minimal reporting of co-workers/fellow students (M = 0.05%, SD = 0.149) or individuals falling into the “other” category (M = 0.009%, SD = 0.058) as relevant network persons, we decided to exclude these two categories from delineating network types.

The remaining structural variables (network size, relative amount of family members, steady partners, MSM chemsex users, MSM non-chemsex users, and friends) were standardised to mitigate scale differences and utilised as clustering variables. Subsequently, hierarchical cluster analysis employing Ward’s minimum-variance method was conducted using squared Euclidean distance as the distance metric (Hair and Black, 2000; Ward, 1963). The resulting dendrogram indicated an optimal cluster solution with three to five clusters. In the second step, three k-means cluster analyses were performed to compare the resulting cluster solutions with three, four, and five clusters. In all three instances, the related ANOVA tables revealed significant differences between clusters on all clustering variables. However, in the case of the three-cluster solution, Tukey post hoc comparisons indicated no significant differences regarding the relative amount of fellow chemsex users between clusters. Similarly, post hoc tests in the five-cluster solutions indicated that the proportions of family members, partners, non-chemsex MSM, and fellow chemsex users did not differ significantly between at least three different clusters. Thus, a cluster solution with four clusters seemed optimal and most meaningful regarding research question 1 since clusters differed significantly on all relevant clustering variables, reflecting the highest structural heterogeneity.

The social network types served as our independent factor to test our prediction regarding hypothesis 1. Thus, we conducted one-way ANOVAs with social support, social influence, and social engagement as dependent measures. Since Levene’s test for equality of variances was found to be violated when social support served as an outcome measure (F (3, 198) = 3.326, p = 0.021), we used Welch’s ANOVA in this case.

Regarding hypotheses 2 and 3, we wanted to test both the effect of social network type and duration of engagement in chemsex on chemsex-related consequences and sexual satisfaction. Therefore, we created a two-level factor from the ordinal scale assessing duration of engagement in chemsex. This resulted in one group displaying chemsex behaviours for more than 5 years and one for less than 5 years. Thus, we performed two separate two-way ANOVAS with a 4 × 2-factorial design, albeit with quite unequal sample sizes (see Table 3).

Finally, to address research question 2, we conducted multivariate linear regression analyses in two models with chemsex-related consequences and sexual satisfaction as dependent variables. In each model we used the following independent variables: all three social resource variables (social support, social influence, and social engagement) as well as all three network quality variables (perceived emotional closeness, perceived reciprocity, and satisfaction with network) and controlled for duration of engagement in chemsex, number of sexual partners within the last 12 months, age, subjective income, and years in full-time education.

Results

Sample description

Table 1 presents a comprehensive overview of sociodemographic variables and chemsex-related aspects. The majority of the sample (over 60%) fell within the 31–50 age bracket, with a substantial proportion having pursued more than eight years of full-time education after the age of 16. Additionally, over half of the respondents perceived their personal income as comfortable or really comfortable (57.6%) and predominantly resided in major cities with over 500,000 inhabitants (65.3%). Respondents reported a substantial prevalence for the sexualised consumption of all substances included. More than 80% of our sample had been practising chemsex for at least 2 years and had a high number of sexual partners in the 12 months before data collection.

Social network types

The network types resulting from the cluster analysis and their means on all clustering variables are presented in Table 2. Each cluster has been assigned a label reflecting the predominant category of individuals represented. Individuals with network type 1 report a social network characterised by a high number of people and diverse composition, with a focus on MSM without sexualised substance use, hence labelled as “MSM-diverse”. Network type 2, named “partner-focused”, is characterised by a relatively small social network with a significantly higher proportion of steady partners compared to the other categories (p < 0.001). In contrast, the majority of individuals within network type 3 are other MSM with sexualised substance use, thus labelled ‘chemsex-restricted’ (p < 0.001). Regarding our hypotheses, this network type was expected to exhibit the least diversity or scope of social resources, along with the least favourable sexual health profile. The final network type was labelled ‘family-diverse’ due to its composition of diverse individuals, primarily comprising family members not found in any of the other three network types (p < 0.001). Furthermore, this social network type differed from the other network types as it was the only one where MSM, regardless of their engagement in chemsex, constituted less than half of the relevant network members.

The structural properties of the derived social network types aligned with the perceived sources of social support. As depicted in Fig. 1, individuals with an MSM-diverse social network type reported receiving social support from a variety of sources, while those with a partner-focused social network identified their steady partners as the primary providers of social support. In the chemsex-restricted network type, social support was predominantly perceived to be provided by MSM engaged in chemsex. Conversely, individuals with a family-diverse network type, unlike all other network types, considered family members to be the most supportive, although similar to the MSM-diverse network type, they also identified relevant individuals from other categories as potentially supportive. Addressing our first research question, the cluster analysis yielded four distinct social network types of chemsex users, characterised by differences in the diversity of social ties and the type of provider for potential social support.

Social network resources

Since the assumption of homogeneity was violated, we obtained results from Welch’s ANOVA for social support. The four network types did not differ regarding the average potential social support (F (3, 68.240) = 1.809, p = 0.154) showing that individuals in each network type reported an equivalent perception of support.

Regarding social influence, however, the network types exhibited significant differences (F (3, 198) = 22.834, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.257) with a large effect. Tukey post hoc comparisons indicated that chemsex users with a MSM-diverse (M = 3.24, SD = 0.62) and family-diverse network type (M = 2.97, SD = 0.64) did not differ significantly from each other (p = 0.435). MSM with a partner-focused social network (M = 3.64, SD = 0.96) perceived significantly more social norms promoting (sexualised) substance use and sexual risk-taking than those in a MSM-diverse (p < 0.05) and in a family-diverse network (p < 0.01). In contrast, respondents with a chemsex-restricted social network reported the strongest social influence (M = 4.14, SD = 0.67), significantly higher than in the MSM-diverse (p < 0.001), the partner-focused (p < 0.01), and the family-diverse networks (p < 0.001). As anticipated, individuals with the most restricted network type perceived their social network to have the highest social influence restricted to approving of sexual risk-taking, substance use, and sexualised substance use.

Similarly, the degree of social engagement differed significantly between network types (F (3, 198) = 9.712, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.128), indicating a medium effect. However, the Tukey post hoc tests revealed no significant differences between the MSM-diverse (M = 8.49, SD = 2.27), partner-focused (M = 7.32, SD = 2.81), and family-diverse networks (M = 7.25, SD = 2.36). In contrast, individuals with a chemsex-restricted social network reported lower social participation (M = 6.09, SD = 2.7) in various social activities with members of their social network compared to respondents with an MSM-diverse network (p < 0.001). Thus, again compared to the other networks, the chemsex-restricted network type was associated with limitations in social engagement.

Indicators of sexual health

Table 3 gives an overview on all groupwise sample sizes, means, standard errors, and 95% confidence intervals for the two dependent measures, i.e. chemsex-related consequences and sexual satisfaction. For chemsex-related consequences, the analysis revealed no main effect for social network type (F (3, 194) = 0.513, p = 0.674). Duration of engagement in chemsex showed a significant, albeit small main effect (F (1, 194) = 4.034, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.020) in the expected direction, i.e. MSM engaged in sexualised substance use for over 5 years reported significantly more negative consequences than those with less than 5 years of chemsex involvement (p < 0.05). The interaction effect did not reach statistical significance (F (3, 194) = 1.7, p = 0.168). Bonferroni-adjusted pairwise comparisons indicated that individuals with a family-diverse network engaged in chemsex for over 5 years (vs. less than 5 years) reported significantly more chemsex-related consequences (p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed for the MSM-diverse (p = 0.108), the partner-focused (p = 0.751), and the chemsex-restricted network type (p = 0.900). The means of all subgroups are depicted in bar graphs in Fig. 2.

The bar graphs illustrating the results regarding sexual satisfaction are presented in Fig. 3. A significant moderate main effect of social network type (F (3, 194) = 3.115, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.046) emerged. However, none of the Tukey post hoc comparisons revealed significant results. Moreover, duration of engagement in chemsex demonstrated a moderate significant main effect (F (1, 194) = 5.404, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.027). As predicted, individuals engaging in chemsex for over 5 years were significantly less sexually satisfied than users with less than 5 years of chemsex experience (p < 0.05). However, the main effects were qualified by a significant interaction effect with a moderate effect size (F (3, 194) = 5.404, p < 0.05, ηp2 = 0.048). Bonferroni-adjusted post hoc analyses revealed that sexual satisfaction did not differ between users with a duration of engagement in chemsex of more or less than 5 years within a MSM-diverse (p = 0.181), a partner-focused (p = 0.33), and a chemsex-restricted social network type (p = 0.204). Conversely, MSM with a family-diverse social network type engaging in sexualised substance use for over 5 years reported significantly lower sexual satisfaction than those with less than 5 years of chemsex involvement (p < 0.01).

Multiple linear regression

Results from the multiple linear regression are shown in Table 4. Regarding chemsex-related consequences, the applied regression model explained a significant proportion of variance (F (11, 190) = 5.101, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.228, R2adjusted = 0.162). None of the social resources significantly predicted the amount of chemsex-related consequences resulting from sexualised substance use. Indicators of network quality, such as perceived reciprocity and satisfaction with the social network, significantly predicted chemsex-related consequences. Increased perceived reciprocity and satisfaction within network relationships were associated with a decrease in chemsex-related consequences. Conversely, an increase in the duration of engagement in chemsex and in the number of sexual partners corresponded to an increase in chemsex-related consequences.

When sexual satisfaction served as a dependent measure, the model explained a significant proportion of variance as well (F (11, 190) = 9.397, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.352, R2adjusted = 0.315). Similar to the findings for chemsex-related consequences, social resources such as social support and social influence did not significantly predict sexual satisfaction. Social engagement, however, significantly predicted sexual satisfacation, i.e. an increase in diverse activities with network members correlated with decreased sexual satisfaction. Additionally, perceived emotional closeness and satisfaction with the network were more effective predictors, while perceived reciprocity did not yield statistical significance. Consistent with the results for chemsex-related consequences, overall network satisfaction emerged as the most influential predictor in the model.

Discussion

The present study examined different social networks of MSM engaged in chemsex and their impact on social resources and sexual health. In addressing research question 1, four distinct social network types were identified, demonstrating notable differences in network composition. While the chemsex-restricted network featured a significant proportion of chemsex users, the partner-focused network comprised primarily respondents’ steady partner, while the remaining two types exhibited a more diverse composition. This aligns with findings from social network research in other populations, highlighting both restricted and diverse social networks (Cheng et al., 2009; Fiori et al., 2006, 2007; Kim and Lee, 2019). Consequently, there appears to be substantial variation in how MSM engaged in chemsex shape their social environment. This underscores the limitations of solely focusing on involvement in or affiliation with the gay community, as observed in prior research (Moody et al., 2018; Petruzzella et al., 2019; Salfas et al., 2019).

Drawing from the concept of homophily (Lazarsfeld and Merton, 1954), we anticipated that limitations in network composition would result in restricted social resources provided by the network (Hypothesis 1). However, we did not find support for this notion in the case of social support. Nevertheless, individuals in the chemsex-restricted network type identified fellow MSM engaged in chemsex as their primary source of social support. Conversely, as predicted, differences were observed in social influence and social engagement. Consequently, chemsex users who predominantly associate with fellow users are subject to heightened social influence promoting sexual risk-taking, substance use, and sexualised substance use. This aligns with previous research indicating that chemsex users perceive sexualised substance use as normative and ubiquitous (Ahmed et al., 2016) and may even view it positively as long as it remains controlled (Deimel et al., 2016).

Users within a chemsex-restricted network also reported significantly lower participation in various social activities with their network members. Notably, 90.9% of respondents with a chemsex-restricted social network reported engaging in chemsex activities with their nominated network members, making it the most frequently reported activity for users with this network type. In summary, our study’s findings indicate that chemsex users within a chemsex-restricted social network are immersed in an environment that predominantly revolves around sexualised substance use.

Regarding hypothesis 2, we assumed that individuals socialising in a chemsex-restricted network would experience more chemsex-related consequences and report lower sexual satisfaction. However, contrary to our predictions, there were no differences between social network types in the prevalence of experienced consequences or subjective sexual satisfaction. Additionally, for hypothesis 3, we expected that MSM engaging in sexualised substance use for an extended period, particularly those in a chemsex-restricted social network, would report poorer sexual health. Users with a duration of engagement in chemsex of more than 5 years did indeed exhibit significantly more chemsex-related consequences and less sexual satisfaction, aligning with prior research demonstrating an accumulation of negative effects over time (Bourne et al., 2015; Hegazi et al., 2017; Platteau et al., 2019; Smith and Tasker, 2018). Unexpectedly, post hoc analyses revealed that users with a family-diverse network and a duration of engagement in chemsex of more than 5 years were particularly at risk for poor sexual health. Conversely, for the other three social network types, both chemsex-related consequences and sexual satisfaction did not differ between users practising chemsex for more or less than 5 years, thus failing to support our initial predictions. Previous research found networks predominantly consisting of MSM to be associated with a higher likelihood for sexual-risk-taking and substance use (Carpiano et al., 2011; Kelly et al., 2012; Peterson et al., 2008). In the present study, however, participants with the least proportion of MSM network members reported the worst outcomes.

This finding may be explained by the unique dynamics of resilience in stigmatised communities, which may differ from those in the general population. Studies have shown that individuals in diverse social networks and those receiving support from family members tend to exhibit better health outcomes (Cheng et al., 2009; Fiori et al., 2006, 2007; Fiori and Jager, 2012). However, as noted by Meyer (2015), for individuals with stigmatised identities to benefit from protective factors provided by similar others, they need to access a sexual minority community. Thus, from the social identity perspective, group identification and social integration are pivotal in promoting psychological adjustment and wellbeing, particularly in the context of stigmatised identities and associated challenges (McLemore, 2018).

The argument posits that individuals who identify fellow chemsex users as significant others may have developed a sense of acceptance and belonging within a valued social group (Jaspal, 2022). From this perspective, they may have acquired a positive social identity through which participation in chemsex activities can serve as a means of coping with stigma and of addressing threats related to sexuality by providing a pathway to community, empowerment, and self-esteem (Jaspal, 2021, 2022; Stanton et al., 2022). Conversely, individuals within a family-diverse network who report the lowest proportion of MSM, with or without chemsex, may perceive aspects of their chemsex social identity as incompatible with their network identities. Specifically, they may experience conflict in simultaneously identifying as a family member and as a chemsex user within their network. This perceived incompatibility can lead to a form of sexual identity conflict, as observed in other populations of MSM. It is known to be associated with compartmentalising identities in terms of denying one identity in the context of the other, and vice versa (Pitt, 2010). Furthermore, in other MSM populations, identity conflict was related to higher rates of guilt and shame (Anderson et al., 2021) which, in turn, can diminish sexual satisfaction and wellbeing (Tatum et al., 2023). Thus, instead of chemsex being associated with a process of positive identity gain (Smith and Tasker, 2018), these users may face additional challenges related to integrating seemingly incompatible aspects of their identity. This may result in isolation from other users, potentially reducing access to chemsex-related social support and indicating heightened levels of minority stress (Jaspal et al., 2022).

In fact, research has demonstrated that attachment to sexual minority communities and receiving social support from other sexual minority individuals is negatively associated with internalised homonegativity and identity concealment (Rosario et al., 2001; Sattler et al., 2016; Williamson, 2000). Self-disclosure, on the other hand, can enhance self-acceptance and contribute to better mental health, serving as a protective factor in the context of chemsex (Jaspal et al., 2022). Therefore, higher group identification and social inclusion among users with a chemsex-restricted social network may be linked to the adoption of risky social norms and behaviour. However, it may also be associated with higher access to valuable social and psychological resources that are beneficial in supporting health, even in the face of a chemsex-promoting environment.

Consequently, from our findings we can deduct six propositions that can be empirically tested in future research: Chemsex users with limited social ties to fellow users might (1) be exposed to a less chemsex-promoting social environment, (2) have less access to chemsex-related resources, (3) show elevated levels of minority stress, guilt, and shame, (4) exhibit less positive and more negative effects of chemsex on sexual and mental health, (5) identify less with the group of MSM engaged in chemsex, and (6) experience sexual identity conflicts.

Finally, the multiple linear regression analyses revealed that qualitative aspects of social networks, such as emotional closeness, perceived reciprocity, and particularly, satisfaction with the nominated network, are strongly associated with sexual health. In this study, high network quality and satisfaction appear to be more relevant for adaptive sexual health in the context of chemsex than social support, social influence, and social engagement. Although some prior research on social support of MSM and other sexual minority individuals did account for heterogeneity of sources for support, these studies mostly applied count measures (e.g. Sattler et al., 2016; Szymanski, 2009) that assume a direct relationship between the quantity of supportive relationships and health (Cutrona and Russell, 1983). However, our results show that the quantity of potential support played a negligible role in predicting sexual health compared to network quality being pivotal. In summary, our results suggest that positive subjective evaluations of personal relationships and social inclusion by fellow users are crucial for MSM engaging in chemsex to sustain health over time.

In our view, the conclusions drawn from the research are relevant in informing interventions aimed at MSM engaged in chemsex. Given the significant influence of network quality on sexual health outcomes, interventions addressing the perceived quality of social connections are likely to be beneficial across different types of social networks that MSM are part of (Chaudoir et al., 2017; Zagic et al., 2022). However, it is also important to consider tailoring interventions to specific network types. For instance, the high perception of social influence in the chemsex-restricted network type underscores the need for community-based interventions addressing social norms (Hammoud et al., 2018). Targeting false perceptions regarding the prevalence of sexualised substance use and actual behaviour within the peer group, known as the false consensus effect, could help counteract the effects of peer conformity (Ahmed et al., 2016; Berkowitz, 2005). Furthermore, involving former users to access chemsex networks has shown promise, as harm-minimisation messages delivered by peers are perceived as more influential. However, reaching users who are more distant from the scene, such as those with a family-diverse network in the current study, may be challenging (Hamilton and Mahalik, 2009; Hugo et al., 2018). For these individuals, integration into a community based on their specific identity needs, comprising MSM with shared chemsex and socialisation experience, may be crucial in establishing valuable social ties (Gaudette et al., 2022). Moreover, they may benefit from reliable information regarding drug effects, chemsex-related risks, and safer sex practices, typically shared within chemsex networks (Herrijgers et al., 2020). Additionally, interventions targeting the cognitive, emotional, and behavioural aspects of minority stress processes (Pachankis et al., 2015) are likely to be beneficial for all MSM engaging in chemsex. However, they seem to be particularly important to consider regarding individuals within a family-diverse network. In addition, this subgroup of users may derive enhanced benefits from identity integration approaches to mitigate the adverse effects of identity conflict on sexual health (Anderson and Koc, 2020).

Apart from intervention strategies, preventive efforts are crucial in addressing sexualised substance use among MSM who have not yet engaged in such behaviours. Research has highlighted the significance of social and sexual connections as primary motivators for initial chemsex behaviour (Platteau et al., 2019). This underscores the importance of community-building initiatives that provide alternative opportunities for affirming sexual identity, fostering meaningful connections, and facilitating open discussions about sex and sexual health (Stall et al., 2007). Additionally, early prevention efforts targeting sexual minority youth should focus on developing social skills and coping mechanisms to address the impact of minority stress on access to social resources, substance use, and sexual health (DiFulvio, 2011; Goldbach et al., 2014).

To our knowledge, our study was the first to derive social networks of MSM engaged in sexualised substance use and to utilise a comprehensive network approach to investigate the quality, social resources, and composition of these networks, as well as their associations with positive and negative outcomes of sexual health. However, the study has some limitations. For instance, while social network analysis is adaptable to various research contexts, this flexibility can reduce the comparability of results. To address this issue, the measures used were guided by previous work or were validated scales adapted to the format of the network survey (e.g. Barman-Adhikari et al., 2017, 2018; Fydrich et al., 2007; Hanson et al., 1997). Furthermore, due to a lack of a validated scale to assess negative consequences of chemsex, the study utilised items from standardised and validated construct-related measures to design an instrument (Allensworth-Davies et al., 2012; Reid et al., 2012). However, the validity of the scale used cannot be confirmed, despite its strong psychometric properties. Additionally, while cluster analysis has been commonly used in previous research (Cheng et al., 2009; Fiori et al., 2006; Litwin and Landau, 2000), replicating results can be challenging due to the dependence on sample, cluster methods, and clustering variables. Moreover, the sizes of each group varied substantially, with only a small number of participants reporting a family-diverse network. Furthermore, potentially relevant variables, such as mental health burdens and subjective experience of minority stressors, were not included in this study to support the conclusions or offer alternative explanations (Bohn et al., 2020; Íncera-Fernández et al., 2021). In addition, the cross-sectional nature of the present study restricts the ability to establish causal relationships from the observational results obtained. Additional research with prospective or longitudinal designs is needed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides valuable insights into the variability and diversity in the composition and social resources of social networks among MSM engaged in chemsex. The findings challenge the prevailing assumptions about the influence of gay community affiliation on social dynamics within chemsex networks, with important clinical implications. From a clinical perspective, our findings underscore the importance of addressing the needs of chemsex users who feel disconnected from any form of community, as they may lack access to essential social connections and resources to mitigate the potential health risks associated with chemsex. By recognising the central role of positive subjective evaluations of personal relationships and social inclusion, clinicians can integrate these findings into therapeutic approaches to promote resilience and well-being among MSM who engage in chemsex. Practical implications for public health should emphasise community-based approaches and tailored interventions. Notable differences in social influence and engagement were observed, suggesting that tailored interventions may be beneficial for individuals within chemsex-restricted networks who are susceptible to heightened influence promoting risky behaviours. Future research should address the present study’s limitations and further explore the clinical utility of our suggestions. This will facilitate the development of targeted interventions that improve the sexual health and overall well-being of MSM engaged in chemsex.

Data availability

Data are stored in a non-public repository due to the sensitive nature of the data collected. Data are, however, available from the corresponding author on request.

Notes

Some definitions of chemsex include solely the consumption of methamphetamine, GHB/GBL and cathinones like mephedrone (Bourne et al., 2015). On the other hand, broader definitions include a greater variety of substances with alcohol, cannabis and amylnitrite being generally excluded (Glynn et al., 2018; Skryabin et al., 2020).

When the explorative factor analysis was performed with the original 5-point scale results did not differ substantially (KMO = 0.94; χ2 (300) = 2749.6, p < 0.001).

References

Ahmed AK, Weatherburn P, Reid D, Hickson F, Torres-Rueda S, Steinberg P, Bourne A (2016) Social norms related to combining drugs and sex (“chemsex”) among gay men in South London. Int J Drug Policy 38:29–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2016.10.007

Allensworth-Davies D, Cheng DM, Smith PC, Samet JH, Saitz R (2012) The Short Inventory of Problems-Modified for Drug Use (SIP-DU): validity in a primary care sample. Am J Addict 21(3):257–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00223.x

Anderson J, Kiernan E, Koc Y (2021) The protective role of identity integration against internalized sexual prejudice for religious gay men. Psychol Relig Spiritual. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000452

Anderson JR, Koc Y (2020) Identity integration as a protective factor against guilt and shame for religious gay men. J Sex Res 57(8):1059–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1767026

Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, Birditt KS (2014) The convoy model: explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. Gerontologist 54(1):82–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt118

Aron A, Aron EN, Smollan D (1992) Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J Pers Soc Psychol 63:596–612

Barman-Adhikari A, Al Tayyib A, Begun S, Bowen E, Rice E (2017) Descriptive and injunctive network norms associated with nonmedical use of prescription drugs among homeless youth. Addict Behav 64:70–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.015

Barman-Adhikari A, Craddock J, Bowen E, Das R, Rice E (2018) The relative influence of injunctive and descriptive social norms on methamphetamine, heroin, and injection drug use among homeless youths: the impact of different referent groups. J Drug Issues 48(1):17–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022042617726080

Barrett DC, Pollack LM (2005) Whose gay community? Social class, sexual self-expression, and gay community involvement. Socio Q 46(3):437–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2005.00021.x

Berkowitz AD (2005) An overview of the social norms approach. In: Lederman LP, Stewart LP (eds) Challenging the culture of college drinking: a socially situated health communication campaign. Hamptom Press, p 193–214

Bohn A, Sander D, Köhler T, Hees N, Oswald F, Scherbaum N, Deimel D, Schecke H (2020) Chemsex and mental health of men who have sex with men in germany. Front Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.542301

Bourne A, Reid D, Hickson F, Torres Rueda S, Weatherburn P (2014) The Chemsex study: drug use in sexual settings among gay and bisexual men in Lambeth, Southwark and Lewisham [Monograph]. Sigma Research, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/2197245/

Bourne A, Reid D, Hickson F, Torres-Rueda S, Weatherburn P (2015) Illicit drug use in sexual settings (‘chemsex’) and HIV/STI transmission risk behaviour among gay men in South London: findings from a qualitative study. Sex Transm Infect 91(8):564–568. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052052

Carpiano RM, Kelly BC, Easterbrook A, Parsons JT (2011) Community and drug use among gay men: the role of neighborhoods and networks. J Health Soc Behav 52(1):74–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395026

Chaudoir SR, Wang K, Pachankis JE (2017) What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “Toolkit. J Soc Issues 73(3):586–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12233

Cheng ST, Lee CKL, Chan ACM, Leung EMF, Lee JJ (2009) Social network types and subjective well-being in chinese older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 64B(6):713–722. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp075

Cialdini RB, Trost MR (1998) Social influence: social norms, conformity and compliance. In: The handbook of social psychology, vols. 1–2, 4th edn, McGraw-Hill, p 151–192

Cutrona C, Russell D (1983) The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones WH, Perlman D (eds) Advances in personal relationships, vol 1. JAI Press, p 37–67

Deimel D, Stöver H, Hößelbarth S, Dichtl A, Graf N, Gebhardt V (2016) Drug use and health behaviour among German men who have sex with men: results of a qualitative, multi-centre study. Harm Reduc J 13(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-016-0125-y

Demant D, Hides L, White KM, Kavanagh DJ (2018) Effects of participation in and connectedness to the LGBT community on substance use involvement of sexual minority young people. Addict Behav 81:167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.028

Dichtl A, Graf N, Sander D (2016) Quadros: Modellprojekt “qualitätsentwicklung in der beratung und prävention im kontext von drogen und sexualität bei schwulen männern (Quadros)”: 2015/2016. Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe, Berlin

DiFulvio GT (2011) Sexual minority youth, social connection and resilience: from personal struggle to collective identity. Soc Sci Med 72(10):1611–1617. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.045

Doty ND, Willoughby BLB, Lindahl KM, Malik NM (2010) Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. J Youth Adolesc 39(10):1134–1147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x

Fiori KL, Antonucci TC, Cortina KS (2006) Social network typologies and mental health among older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 61(1):25–P32. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.P25

Fiori KL, Jager J (2012) The impact of social support networks on mental and physical health in the transition to older adulthood: a longitudinal, pattern-centered approach. Int J Behav Dev 36(2):117–129. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411424089

Fiori KL, Smith J, Antonucci TC (2007) Social network types among older adults: a multidimensional approach. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 62(6):P322–330. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.6.p322

Frost DM, Meyer IH, Schwartz S (2016) Social support networks among diverse sexual minority populations. Am J Orthopsychiatry 86(1):91–102. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000117

Fydrich T, Sommer G, Tydecks S, Brähler E (2007) Fragebogen zur sozialen Unterstützung (F-SozU). Social Support Questionnaire (F-SozU). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Gaudette Y, Flores-Aranda J, Heisbourg E (2022) Needs and experiences of people practising chemsex with support services: toward chemsex-affirmative interventions. J Mens Health 18(12):57–67. https://doi.org/10.22514/jomh.2022.003

Glynn RW, Byrne N, O’Dea S, Shanley A, Codd M, Keenan E, Ward M, Igoe D, Clarke S (2018) Chemsex, risk behaviours and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men in Dublin, Ireland. Int J Drug Policy 52:9–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.10.008

Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S (2014) Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: a meta-analysis. Prev Sci 15(3):350–363. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0393-7

Hamilton CJ, Mahalik JR (2009) Minority stress, masculinity, and social norms predicting gay men’s health risk behaviors. J Couns Psychol 56(1):132–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014440

Hair JF, Black WC (2000) Cluster analysis. American Psychological Association

Hammoud MA, Bourne A, Maher L, Jin F, Haire B, Lea T, Degenhardt L, Grierson J, Prestage G (2018) Intensive sex partying with gamma-hydroxybutyrate: factors associated with using gamma-hydroxybutyrate for chemsex among Australian gay and bisexual men - results from the Flux Study. Sex Health 15(2):123–134. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17146

Hanson BS, Östergren PO, Elmståhl S, Isacsson SO, Ranstam J (1997) Reliability and validity assessments of measures of social networks, social support and control—results from the Malmö Shoulder and Neck Study. Scand J Soc Med 25(4):249–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/140349489702500407

Hegazi A, Lee M, Whittaker W, Green S, Simms R, Cutts R, Nagington M, Nathan B, Pakianathan M (2017) Chemsex and the city: sexualised substance use in gay bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. Int J STD AIDS 28(4):362–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462416651229

Herrijgers C, Poels K, Vandebosch H, Platteau T, van Lankveld J, Florence E (2020) Harm reduction practices and needs in a Belgian chemsex context: findings from a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(23):9081. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17239081

Hibbert MP, Brett CE, Porcellato LA, Hope VD (2019) Psychosocial and sexual characteristics associated with sexualised drug use and chemsex among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the UK. Sex Transm Infect 95(5):342–350. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2018-053933

Holt M (2011) Gay men and ambivalence about ‘gay community’: from gay community attachment to personal communities. Cult Health Sex 13(8):857–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2011.581390

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7(7):e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hotton AL, Keene L, Corbin DE, Schneider J, Voisin DR (2018) The relationship between Black and gay community involvement and HIV-related risk behaviors among Black men who have sex with men. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 30(1):64–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2017.1408518

Hugo JM, Rebe KB, Tsouroulis E, Manion A, De Swart G, Struthers H, McIntyre JA (2018) Anova Health Institute’s harm reduction initiatives for people who use drugs. Sex Health 15(2):176–178. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17158

Íncera-Fernández D, Gámez-Guadix M, Moreno-Guillén S (2021) Mental health symptoms associated with sexualized drug use (chemsex) among men who have sex with men: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413299

Jaspal R (2021) Chemsex, identity processes and coping among gay and bisexual men. Drugs Alcohol Today 21(4):345–355. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-12-2020-0083

Jaspal R (2022) Chemsex, identity and sexual health among gay and bisexual men. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912124

Jaspal R, Lopes B, Breakwell GM (2022) Minority stressors, protective factors and mental health outcomes in lesbian, gay and bisexual people in the UK. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03631-9

Kelly BC, Carpiano RM, Easterbrook A, Parsons JT (2012) Sex and the community: the implications of neighbourhoods and social networks for sexual risk behaviours among urban gay men. Socio Health Illn 34(7):1085–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2011.01446.x

Kertzner RM, Meyer IH, Frost DM, Stirratt MJ (2009) Social and psychological well-being in lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals: the effects of race, gender, age, and sexual identity. Am J Orthopsychiatry 79(4):500–510. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016848

Kim YB, Lee SH (2019) Social support network types and depressive symptoms among community-dwelling older adults in South Korea. Asia Pac J Public Health 31(4):367–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539519841287

Laireiter A (1993) Soziales netzwerk und soziale unterstützung: konzepte, methoden und befunde. Huber, Bern

Lazarsfeld PF, Merton RK et al. (1954) Friendship as a social process: a substantive and methodological analysis. Freedom Control Mod Soc 18(1):18–66

Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Pachankis JE, Golub SA, Walker JJ, Bamonte AJ, Parsons JT (2013) Age cohort differences in the effects of gay-related stigma, anxiety and identification with the gay community on sexual risk and substance use. AIDS Behav 17(1):340–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0070-4

Litwin H, Landau R (2000) Social network type and social support among the old-old. J Aging Stud 14(2):213–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(00)80012-2

Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ (2006) FACTOR: a computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav Res Methods 38(1):88–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03192753

Masini BE, Barrett HA (2008) Social support as a predictor of psychological and physical well-being and lifestyle in lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults aged 50 and over. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv 20(1–2):91–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720802179013

Maxwell S, Shahmanesh M, Gafos M (2019) Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 63:74–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.11.014

McLaren S, Jude B, McLachlan AJ (2008) Sense of belonging to the general and gay communities as predictors of depression among Australian gay men. Int J Mens Health 7(1):90–99. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0701.90

McLemore KA (2018) A minority stress perspective on transgender individuals’ experiences with misgendering. Stigma Health 3(1):53–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000070

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM (2001) Birds of a feather: homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Socio 27(1):415–444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Meyer IH (2003) Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 129(5):674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

Meyer IH (2015) Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers 2(3):209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

Møller K, Hakim,J (2021) Critical chemsex studies: interrogating cultures of sexualized drug use beyond the risk paradigm. Sexualities. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634607211026223

Moody RL, Starks TJ, Grov C, Parsons JT (2018) Internalized homophobia and drug use in a national cohort of gay and bisexual men: examining depression, sexual anxiety, and gay community attachment as mediating factors. Arch Sex Behav 47(4):1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1009-2

Neto F (2012) The Satisfaction With Sex Life Scale. Meas Eval Couns Dev 45(1):18–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175611422898

Neyer FJ, Wrzus C, Wagner J, Lang FR (2011) Principles of relationship differentiation. Eur Psychol 16(4):267–277. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000055

Pachankis JE, Hatzenbuehler ML, Rendina HJ, Safren SA, Parsons JT (2015) LGB-affirmative cognitive-behavioral therapy for young adult gay and bisexual men: a randomized controlled trial of a transdiagnostic minority stress approach. J Consult Clin Psychol 83(5):875–889. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000037

Pakianathan M, Whittaker W, Lee MJ, Avery J, Green S, Nathan B, Hegazi A (2018) Chemsex and new HIV diagnosis in gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men attending sexual health clinics. HIV Med. https://doi.org/10.1111/hiv.12629

Peterson JL, Rothenberg R, Kraft JM, Beeker C, Trotter R (2008) Perceived condom norms and HIV risks among social and sexual networks of young African American men who have sex with men. Health Educ Res 24(1):119–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyn003

Petruzzella A, Feinstein BA, Davila J, Lavner JA (2019) Moderators of the association between community connectedness and internalizing symptoms among gay men. Arch Sex Behav 48(5):1519–1528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1355-8

Pitt RN (2010) ‘Still looking for my Jonathan’: gay Black men’s management of religious and sexual identity conflicts. J Homosex 57(1):39–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918360903285566

Platteau T, Pebody R, Dunbar N, Lebacq T, Collins B (2019) The problematic chemsex journey: a resource for prevention and harm reduction. Drugs Alcohol Today 19(1):49–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-11-2018-0066

Pollard A, Nadarzynski T, Llewellyn C (2018) Syndemics of stigma, minority-stress, maladaptive coping, risk environments and littoral spaces among men who have sex with men using chemsex. Cult Health Sex 20(4):411–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1350751

Reid RC, Garos S, Fong T (2012) Psychometric development of the hypersexual behavior consequences scale. J Behav Addict 1(3):115–122. https://doi.org/10.1556/JBA.1.2012.001

Rosario M, Hunter J, Maguen S, Gwadz M, Smith R (2001) The coming-out process and its adaptational and health-related associations among gay, lesbian, and bisexual youths: stipulation and exploration of a model. Am J Community Psychol 29(1):133–160. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005205630978

Salfas B, Rendina HJ, Parsons JT (2019) What is the role of the community? Examining minority stress processes among gay and bisexual men. Stigma Health 4(3):300–309. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000143

Sattler FA, Wagner U, Christiansen H (2016) Effects of minority stress, group-level coping, and social support on mental health of german gay men. PLoS ONE 11(3):e0150562. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150562

Singer MC, Erickson PI, Badiane L, Diaz R, Ortiz D, Abraham T, Nicolaysen AM (2006) Syndemics, sex and the city: understanding sexually transmitted diseases in social and cultural context. Soc Sci Med 63(8):2010–2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.012

Skryabin V, Bryun E, Maier L (2020) Chemsex in Moscow: investigation of the phenomenon in a cohort of men who have sex with men hospitalized due to addictive disorders. Int J STD AIDS 31(2):136–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462419886492

Smith V, Tasker F (2018) Gay men’s chemsex survival stories. Sex Health 15(2):116. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH17122

Stall R, Friedman M, Catania J (2007) Interacting epidemics and gay men’s health: a theory of syndemic production among urban gay men. In: Wolitski RJ, Stall R, Valdiserri RO (eds) Unequal opportunity: health disparities affecting gay and bisexual men in the United States. Oxford University Press, Oxford, p 251–274

Stanton AM, Wirtz MR, Perlson JE, Batchelder AW (2022) “It’s how we get to know each other”: substance use, connectedness, and sexual activity among men who have sex with men who are living with HIV. BMC Public Health 22(1):425. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-12778-w

Stuart D (2019) Chemsex: origins of the word, a history of the phenomenon and a respect to the culture. Drugs Alcohol Today 19(1):3–10. https://doi.org/10.1108/DAT-10-2018-0058

Szymanski DM (2009) Examining potential moderators of the link between heterosexist events and gay and bisexual men’s psychological distress. J Couns Psychol 56(1):142–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.56.1.142

Tatum AK, Niedermeyer T, Schroeder J, Connor JJ (2023) Shame as a moderator of attachment and sexual satisfaction. Psychol Sex 0(0):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2023.2297394

Teixeira da Silva D, Bouris A, Voisin D, Hotton A, Brewer R, Schneider J (2020) Social networks moderate the syndemic effect of psychosocial and structural factors on HIV risk among young Black transgender women and men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav 24(1):192–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02575-9

Ward JH (1963) Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J Am Stat Assoc 58(301):236–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1963.10500845

Williamson IR (2000) Internalized homophobia and health issues affecting lesbians and gay men. Health Educ Res 15(1):97–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/15.1.97

Zagic D, Wuthrich VM, Rapee RM, Wolters N (2022) Interventions to improve social connections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57(5):885–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02191-w

Acknowledgements

We used Large Language Models (LLMs) as artificial intelligence-based technologies from Scite.ai for the sole purpose of improving the readability and language editing of the manuscript after the first draft was written. The authors would like to thank Hannah Buchbauer for proofreading the final draft.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZH designed the study, recruited study subjects, provided literature searches, wrote the first draft and undertook the statistical analyses. HU recruited study subjects, provided critical feedback and supervised the study design. VMS provided critical feedback, edited and rewrote the introduction and discussion of the first draft. PB provided critical feedback, edited and rewrote the first and final draft, provided statistical analysis and supervised the project. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All human subjects provided written informed consent with guarantees of confidentiality. The survey was submitted to the Ethics Review Committee of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin (project identification code: EA1/328/21).

Informed consent

Our research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hille, Z., Ulrich, H., Straßburger, V.M. et al. Social networks of men who have sex with men engaging in chemsex in Germany: differences in social resources and sexual health. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 380 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02871-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02871-3