Abstract

This study aims to investigate the translation styles from the perspective of text complexity and to elucidate underlying factors contributing to the formation of stylistic differences based on individuation. Using SysFan and SPSS22.0 as tools, a combined quantitative and qualitative approach is employed to comparatively analyze the lexical density and grammatical intricacy across the renowned ancient Chinese poem Pipa Xing 琵琶行and its nine English translations. The findings reveal that while the translations exhibit comparable levels of lexical density, disparities in complexity primarily manifest in terms of grammatical intricacy, reflecting distinct text features: spoken, written, and mixed spoken and written, as well as varying degrees of hierarchical and narrative features. The variations in translation styles are intricately linked to the individuation process undergone by translators. The translator’s individuation process is modeled to show how a translator mobilizes the meaning resources in the repertoire, which is constrained by the allocation of the cultural reservoir, to re-instantiate the source text in the translated text, while constructing affiliation with the target-reader community. Different translators’ allocated repertoires ultimately shape their conscious or unconscious choices in terms of lexicogrammar, thereby generating translated texts characterized by diverse styles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pipa Xing, a celebrated masterpiece by Bai Juyi (Po Chü-i) within the illustrious and influential realm of Tang poetry, takes its place as a shining gem during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 C.E.), the golden age of Chinese verse. Among the luminaries of Tang poetry, Bai Juyi stands tall, renowned for his accessible writing style and focus on ordinary human experiences. Within Bai’s formidable literary repertoire, Pipa Xing stands as an exceptional pinnacle to exemplify the apex of his poetic craftsmanship, encapsulating his artistic philosophy and mastery, and seamlessly blending lyricism and narrative (Jian, 1994). In this poem, Bai constructs a narrative arc around his encounter with a talented pipa player, shedding light on the miserable lives of ordinary people and the injustice within the imperial regime during the mid-Tang Dynasty, and underscoring the impact of music that invokes the poet’s empathy. Chen (1950) gives much credit to Pipa Xing as an ancient poem unsurpassed by later creations. The extensive influence of Pipa Xing also permeates the modern literary contributions beyond the boundaries of China. For instance, Kenneth Rexroth offers a variation in his poem Another Spring, “the white moon enters the heart of the river” (Rexroth, 1966, p. 145), drawn from the original verse “wéi jiàn jiāng xīn qiū yuè bái” (唯见江心秋月白) in Pipa Xing.

For more than a century, this poetic gem has been rendered into English by a cadre of translators, each imbuing the verses with their unique perspectives and linguistic prowess. This study embarks on an exploration of these different translated versions, adopting text complexity as an indicator to study translation styles, and employing the dimension of individuation to elucidate the factors that underlie the formation of those stylistic diversity.

Systemic Functional Linguistics (hereafter SFL) posits that grammar is a theory for construing human experience. Grammar, or lexicogrammar, serves to manage the complexity of human existence, with its multifunctionality – “a construal of human experience, and an enactment of the social process” (Halliday, 2009, p. 74). Thus the exploration of language complexity at the textual level focuses on lexicogrammatical complexity. In studies of translation, text complexity is a part of style and influences translation style (Izquierdo and Borillo, 2000; Yu and Wu, 2017).

From the perspective of translation generation, translation is a meaning-oriented process of re-instantiation based on the source text (hereafter ST). Multiple translations of the same ST result from different translators’ re-instantiation of the ST (Chang, 2018; Martin and Quiroz, 2021; see also Matthiessen, 2001). This process and its outcomes are influenced by various factors, with the individuation of translators being a crucial aspect. Translators occupy a central role in the translation activity, determining its direction and results. The subjectivity of translators is one of the central concerns in translation studies (c.f. Venuti, 1992, 1998, 2008, 2021). The relationship between the sociocultural context (including the contexts of creation, translation, and reception) and the participants in the translation activity (such as the author, translator, and target readers) has been discussed extensively in academia (e.g., Schäffner and Holmes, 1995; Lefevere, 2017; Nord, 2018, etc.). The theory of individuation enriches the field of translation study by offering a perspective on how the sociocultural context affects the translator’s choices that are realized in the translated text.

Individuation within SFL primarily concerns the distribution of semiotic resources among individuals within a given culture and the formation of diverse communities among these individuals (Martin and Quiroz, 2021). In the context of translation, individuation serves as a framework for examining how translators employ the allocated resources in their source and target language repertoires, and establish affiliations with a specific readership. It delves into the intricate process through which translators, while operating within the constraints of cultural contexts and other pertinent factors, engage in the act of translation itself (Wang, 2021). On the one hand, individuation explores how translators, in their roles as agents of translation, draw upon their repertoire of meaning resources derived from their cultural reservoirs to comprehend the expression of the author’s meaning resources within the ST. On the other hand, it analyzes how translators align themselves with the intended readership in the target language. It is noted that a translator’s choices, including both resource allocation and affiliation decisions, exert an immediate and profound influence on the resulting translated text.

This study, grounded in SFL, utilizes a corpus of the ancient Chinese narrative poem Pipa Xing and its nine English translations to investigate the relationship between translation style variations and the process of translator individuation, employing a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. The study aims to address the following two questions:

-

(1)

What kind of styles and their differences do the various translations exhibit in terms of text complexity?

-

(2)

From the perspective of individuation, how do translators, based on their identities, exert subjectivity in the translation process to allocate meaning resources and align with the target readership, ultimately influencing translation styles?

Theoretical framework

This section offers the theoretical underpinnings that inform the current study. It begins by elucidating the three-dimensional model of language that enables a comprehensive landscape of translation by including language systems, text, and participants involved in translation activity. Then the concept of text complexity is introduced as the main indicator for the study of translation styles. Finally, the study discusses the concept of individuation, one of the three complementary dimensions, which concerns translation participants operating in context, and facilitates the elucidation of the underlying factors contributing to the formation of stylistic differences.

Three-dimensional model of language and translation

SFL posits that language is a resource for creating meaning, and meaning resides in a systemic pattern of choices. While systems combine to form a network, a text is “the product of ongoing selection” within this network of systems (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, p. 23). The construction of meaning involves three dimensions: phylogenesis (“the evolution of human language”), logogenesis (“the unfolding of the act of meaning itself”, i.e., the construction of meaning in the form of a text), and ontogenesis (“the development of the individual language user”) (Halliday and Matthiessen, 1999, pp. 17-18). These three dimensions correspond to the complementary dimensions of the language model: instantiation, realization, and individuation (see Fig. 1).

Realization, stemming from the fundamental characteristic of language as a stratified system (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014), pertains to the relationship across the strata, “the relationship of symbolization” in which each stratum is “a resource at a particular order of abstraction” (Matthiessen, 1995, pp. 3-4). It links one stratum to another and describes how higher-level strata are realized in lower-level strata. In the content plane, the stratum of semantics (meaning) is realized in the stratum of lexicogrammar (wording), where lexis and grammar lie in a continuum (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014).

In the study of translation, the lexicogrammatical stratum within the realization dimension provides meaning resources for exploring translation styles concerning text complexity, while translation is modeled as a process of re-instantiation of the meaning potentials from the original text to the target text (hereafter TT). As a complementary perspective, the individuation dimension explains why different interpretations arise during the translation process, affecting the outcomes of translated texts from the translator’s perspective.

Text complexity and translation

As “language is a semogenic system which creates meaning”, this system operates at a “fourth-order complexity” level, encompassing the physical realm, the biological one “with added life”, the social one “with added value”, and the semiotic one “with added meaning” (Halliday, 2003, p. 412). Matthiessen et al. (2022) applie the ordered typology of systems to locate translation issues. For instance, the fundamental aspect of translation involving choice in meaning and recreation of meaning is a fourth-order property; the translator’s role within teams of other professionals and clients is a third-order property, while the nature of the translator’s memory is a second-order property.

Along the cline of instantiation that connects language system and instance of language in use, text locates at the instance pole and enacts meanings in context, carrying out the meaning potential of the system and exhibiting the multifaceted characteristics of language. For example, properties such as interaction, diversity, and stratification are evident in a text through the textual metafunction (He and Guo, 2020).

Among the properties of text, text complexity is a multidimensional construct (Biber, 1992), and has been measured from different perspectives (Lassen, 2003; Barbaresi, 2003; Fang, 2006; Sauro and Smith, 2010). Halliday (2009, p. 74) delves into the complexity with a specific focus on lexicogrammar in text, regarding lexicogrammar as “a theory of the human condition – a construal of experience and an enactment of the social process”, which semiotizes the material environment through two different ways: lexicalized and grammaticalized meanings. In the lexis, complexity manifests in increasing density, while in grammar, it manifests as heightened intricacy. Thus text complexity can be examined by two parameters: lexical density (hereafter LD) and grammatical intricacy (hereafter GI) (Halliday, 2009; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014; Huang and Liu, 2015; Yu and Wu, 2017).

LD refers to the proportion of lexical items (content words) within a given unit of grammar. In a text, LD reflects the ratio of lexical items (content words) to the total number of ranking clauses. This measurement determines the information density of the discourse: the higher the level of LD, the more information the discourse contains.

GI is related to the intricate construction patterns of sentences, which are manifested through the complexity of taxis (interdependency relationships) and logico-semantic relations (Halliday, 1989, 2009). Here “sentence” refers to the one in the traditional grammatical sense, marked by a full-stop graphologically. Language users can either adopt a sentence that contains one ranking clause only, i.e., a clause simplex, or a sentence that contains more than one multiple ranking clauses, i.e., a clause complex (Matthiessen, 1995). The relations in a clause complex can be grouped into taxis and logico-semantics. Taxis describes “the degree of interdependency” between ranking clauses in a clause complex, including parataxis (labelled with a numerical notation 1, 2 …for initiating and continuing clauses) and hypotaxis (labelled with a Greek notation α, β …for dominant and dependent clauses), while logico-semantic relations describe “the relationships of expansion and projection” (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, p. 440, p. 443).

In logico-semantic relationships, on the one hand, projection establishes connections between phenomena of one lower order of experience (the processes of speaking and thinking) and phenomena of a higher order (semiotic phenomena, i.e., what people say and think). What is projected can be either a locution (“) or an idea (‘). On the other hand, expansion establishes connections between phenomena as being of the same order of experience, which can be further divided into elaboration (=), extension (+), and enhancement (x). Elaboration refers to expanding a clause by expounding upon another, restating in other words, specifying in greater detail and depth, commenting, or exemplifying. Extension refers to expanding a clause by adding some new element, presenting an exception to it, or offering an alternative. Enhancement refers to expanding a clause by embellishing it: qualifying it with circumstantial details like time, place, cause, or condition. These relationships shape a tighter integration in meaning. The categories and labels of taxis and logico-semantic relations are presented in Table 1 (for details see Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014, pp. 428–548).

GI is calculated through dividing the number of ranking clauses by the total number of sentences (including clause complexes and clause simplexes). This measure reflects the grammatical complexity of the text: the higher the level of GI, the more complex the grammatical structures in the text, indicating more intricate taxis and logico-semantic relations within the text. Moreover, within the tactic relationships, hypotaxis contains more layers and thus is more hierarchical and complex than parataxis (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014; Lord, 2002; Yu and Wu, 2017). It is also noted that as for logico-semantic relations, enhancement is quite frequent in narratives, construing sequences of events, as stories develop mainly through temporal enhancement (Matthiessen, 2002).

Generally, spoken texts increase complexity by enhancing GI, while written texts augment complexity by increasing LD (Halliday, 1989; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014). In translation studies, differences in text complexity manifest as variations in textual style among different translations of the same ST (Izquierdo and Borillo, 2000; Yu and Wu, 2017).

Individuation and translation

Individuation focuses on language users and concerns the relationship between the general cultural semiotic resources (reservoir of culture) and the complete resources that specific individuals can access (repertoire of individual) (Martin, 2008, 2009, 2010; Martin et al., 2013, etc.). The process of individuation is achieved through resource allocation and affiliation. Allocation refers to the process of transferring meaning resources from the cultural reservoir to the individual repertoire. This involves how social semiotic resources are differentially allocated to “master identities (including nationality, social roles, gender, class, race, etc.) and subcultures”, ultimately reaching “the personas that compose individual members” (Martin, 2010, p. 24). Affiliation refers to the alignment process from the individual repertoire back to the cultural reservoir. It encompasses how individuals mobilize social semiotic resources to establish alignments or belongings of different orders, shape identity in a community (“including relatively ‘local’ familial, collegial, professional, and leisure/recreational affiliations”, etc.), construct master identity, and ultimately form mainstream cultures (Martin et al. 2013, p. 490).

Translation involves more than just linguistic transference of the ST. As Lefevere (1992) argues, it is also a creative process on the cultural level, shaped by the literary, ideological, and cultural systems of the translator’s era. Additionally, Bourdieu (1977, 1991) conceives translation as an interaction between various agents, including the author, commissioner, publisher, editor, and reader, situating the translator and other participants within the process. The role and involvement of the translator become focal points, as prominently addressed in Venuti’s discussion of translator invisibility (2008). According to Venuti (2008), the subjectivity of the translator, which is constituted by diverse, even conflicting cultural and social determinations that mediate language use, shapes the production of translated texts through the activation of linguistic and cultural resources, potentially creating discontinuities and an unconscious dimension in the text. Therefore, how translations take form is confined and driven by subjectivity based on the social and cultural situatedness of the translator.

Translator’s individuation process has a deep impact on the generation of a translation that is shaped by the subjectivity of the translator. In the translation process, the translator’s differential access to the cultural reservoir of meaning potential is consequential, impacting their interpretation of the ST and capacity to reconstrue it appropriately in the TT. Meanwhile, the translator’s affiliations with both the original author and target readers also mediate the process, as they orient to the two cultural groups and make decisions regarding semantic equivalence versus shifts that may be more aligned with target language norms and expectations. Overall, accounting for the individuation process of the translator is key to understanding factors that constrain, shape, and motivate the translator’s choices in translation process.

Data and research methods

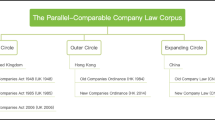

The ancient Chinese poem Pipa Xing and its nine English translations

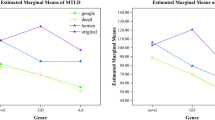

This study employs the ancient Chinese poem Pipa Xing and its nine English translations as the corpus, and the basic information is shown in Table 2. Drawing on Martin’s hierarchy of individuation (2010), nationality as a salient master identity facet serves to categorize the translators into three clusters: Chinese (Xu Yuanchong, Lin Yutang), British or American (Cranmer-Byng, Watson, Gaunt, Giles) and Sino-Western collaborative (Yang and Gladys; Zhang and Wilson; Bynner and Kiang). Thus the translated versions in this corpus respectively represent the works of Chinese, British/American, or bicultural cooperative translator teams situated across literary and historical spaces.

The translators hold multifaceted affiliations spanning cultural disseminator to poet and sinologist. As such, translator-writer Lin Yutang, poets Bynner and Cranmer-Byng, eminent sinologists Giles and Watson, and literature scholars Zhang and Wilson exhibit distinct trajectories of professional affiliation. These individuated cultural and epochal positions, along with aligned readerships, stand to uniquely shape their translation choices, which will be explored in Section “Discussion: an individuation perspective”.

Research methods and procedures

SysFan and SPSS22.0 are used as the main tools in this study. A combination of quantitative and qualitative analyses is carried out to compare the complexity of the different translations. SysFan is a computational tool for facilitating text analysis from a systemic functional perspective. It aids in the annotation of taxis and logico-semantic relationships above ranking clauses (see Fig. 2). Additionally, it automatically computes a range of statistical data for each text, including word count, clause count, sentence count, LD, and GI (Wu, 2009; Yu and Wu, 2017). The statistical software SPSS22.0 is utilized to test for significant differences in the data obtained from each translation.

The annotation of taxis and logico-semantic relations in SysFan adopts the labels shown in Table 1. In annotating grammatical boundaries, clause boundary is indicated by “||”, and the boundary of clause complex is indicated by “|||” (see Example 1 below). This study adopts the criteria for defining clauses and clause complexes in Chinese and English as elucidated by Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) as well as He and Wang (2019). A clause contains a Predicator realized by a main verb in English, or a Predicator Element realized by a main verb, noun group, quality group, quantity group, or other groups in Chinese.

In calculating the LD of the translations, to avoid the influence of function words on the statistical results, Cook’s function word listFootnote 1 (consisting of 225 words) is adopted for filtering purposes. This ensures that only the ratio of lexical items to ranking clauses is taken into account. In calculating the LD of the original poem, a system of the Chinese part of speech (POS) is constructed for annotation, distinguishing lexical items and function words based on Wang’s standard (2015). This system classifies Chinese “nouns, adjectives, verbs, pronouns, quantifiers” and “most of adverbs serving as adverbial” (e.g., Tū 突, jiē 皆, zuì 最) into the category of lexical item (Wang, 2015, p. 319, p. 328). In addition, Chinese “prepositions, conjunctions, auxiliary words, modal-particles, exclamations”, and “some of adverbs functioning as conjunctive” (e.g., yòu 又, yǐ 已) are classified into the category of function word (Wang, 2015, pp. 328–329).

LD and GI are calculated in SysFan using the following formulas, as mentioned in Halliday (2009):

Degree of Lexical Density= number of lexical items/number of ranking clauses.

Degree of Grammatical Intricacy= number of ranking clauses/number of sentences.

The analysis includes the following steps. Firstly, based on the scales in semantics (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014), the schematic structure of genres (Martin and Rose, 2008), and the narrative sequence of Pipa Xing, the study divides the original poem into six rhetorical paragraphs or stages labeled by “S” (see Table 3). Secondly, all data are further divided, numbered, and aligned at the level of text, stages, sentences (including clause simplexes and clause complexes), and clauses within each clause complex. Then all the processed data are imported into SysFan for the annotation of taxis and logico-semantic relations, thereby constructing a database and providing statistical results automatically. Next, comparisons are made between the overall and stage-specific levels of LD and GI for each text, and SPSS 22.0 is used to conduct statistical tests on the data groups to determine if significant differences exist. Subsequently, taxis and logico-semantic relations within each text are further analyzed to compare their hierarchical and narrative characteristics. Additionally, the results from these analyses are synthesized to summarize the similarities and differences in the styles of each translation. Finally, the individuation perspective is employed to explore the factors contributing to these variations.

Data analysis: lexical density and translation styles

LD is one of the parameters used to measure text complexity. The LD of a translation reflects the translator’s choices in representing the amount of information during translation. Figure 3 displays the LD of Pipa Xing and its nine translations both overall and in various stages. The overall LD of each text is linked by a dark line, and the stage-specific variation of LD in each text is represented in distinct columns.

To further examine whether there are significant differences in LD among the ten texts, this study conducts a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) on the data. SPSS 22.0 results show that the data reasonably follow a normal distribution based on the Shapiro-Wilk test, and the variance homogeneity is confirmed. The result of the ANOVA yields p = 0.159, exceeding the significance threshold of 0.05. Consequently the statistical results are not significant, suggesting no significant difference among the LD levels of the ten texts.

To illustrate the comparison of the LD in each translation, an example from S4 of the text, translated by T3, T5, T9, and T10, is presented as follows. A transcription of Chinese pinyin and a literal translation are given to better exemplify the segment in the original text. Lexical items are highlighted in bold in all texts and separated by added spaces in the ST and its transcription.

Example 1 Lexical density of T1, T3, T5, T9, T10

Segment | LD | |

|---|---|---|

T1_ST | ||| 我 闻 琵琶 || 已 叹息, || 又 闻 此 语 || 重 唧唧。||| 同 是 天涯 沦落 人, || 相 逢 || 何必 曾 相 识。||| | 2.86 |

Wǒ wén pípá yǐ tànxī, yòu wén cǐ yǔ chóng jījī. Tóng shì tiānyá lúnluò rén, xiāng féng hébì céng xiāng shí. | ||

Literal translation: I sighed when I heard the pipa, and sighed again when I heard the words. We are both fallen people at the end of the world, so why we should have known each other before. | ||

T3_Yang & Yang | ||| The music of her lute has made me sigh, || and now she tells this plaintive tale of sorrow; || we are both ill-starred, || drifting on the face of the earth; || no matter if we were strangers before this encounter. ||| | 3.00 |

T5_Zhang & Wilson | Already, the pipa’s song had made me sign, ||but these words made me utterly forlorn. |||Both losers in this wider world, ||by chance both here, ||it mattered not that we had never met before. ||| | 2.80 |

T9_Gaunt | ||| When first I heard the lute, || my heart was pierced by sympathy’s quick dart; || but when I heard this tale, || the pain in frequent sighs broke out again. ||| “Companions in adversity in this wild spot,” I cried, || “are we; || and those thus met, || what need have they convention’s canons to obey || ere they hold intercourse of speech, || though erstwhile each unknown to each? ||| | 2.80 |

T10_Giles | ||| The sweet melody of the lute had already moved my soul to pity, || and now these words pierced me to the heart again. ||| “O lady,” I cried, || “we are companions in misfortune, || and need no ceremony to be friends. ||| | 3.00 |

The four translations show similar LD levels in this segment, with T3 matching T10 and T5 matching T9. However, it is important to note that there are significant differences in the number of lexical items between T5 (the number of lexical items = 14) and T9 (the number of lexical items = 28). Their consistency in LD level arises from differences in grammatical structures. As Example 2 demonstrates, despite the fact that both segments T5 and T9 consist of two sentences in each case, they are notably different. Specifically, the segment from T5 features a clause complex with two clauses in paratactic enhancement and another with three clauses in hypotactic enhancement in which the two dependent clauses are in ellipsis (labeled as “∩E”). Comparatively, the segment of T9 exhibits heightened complexity in terms of both the number of clause and hierarchical feature. Sentence 33 in T9 is composed of two clause complexes in paratactic relations, with each consisting of two clause complexes in hypotactic enhancement. Moreover, Sentence 34 is structured with two clauses and a clause complexes, where the latter two are projections of the primary one. In the last clause complex (“projection: locution”), it encompasses four clauses in hypotactic enhancement. These differences reflect variations in GI and hierarchy, which are expounded in the following section.

Example 2 The grammatical structure and semantic relations in examples of T5 and T9

Text | Sent. No. | Cl. No. | Relations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

T5_ Zhang & Wilson | 29 | 1 | 1 | Already, the pipa’s song had made me sign, | |

2 | x2 | but these words made me utterly forlorn. | |||

30 | 1 | xγ∩E | Both losers in this wider world, | ||

2 | xβ∩E | by chance both here, | |||

3 | α | it mattered not that we had never met before. | |||

T9_ Gaunt | 33 | 1 | 1 | xβ | When first I heard the lute, |

2 | α | my heart was pierced by sympathy’s quick dart; | |||

3 | +2 | xβ | but when I heard this tale, | ||

4 | α | the pain in frequent sighs broke out again. | |||

34 | 1 | 1 | I cried, | ||

2 | “2 | “Companions in adversity in this wild spot, are we; | |||

3 | “3 | xβ | and those thus met, | ||

4 | α | what need have they convention’s canons to obey | |||

5 | xγ | ere they hold intercourse of speech, | |||

6 | xδ | though erstwhile each unknown to each? | |||

Data analysis: grammatical intricacy and translation styles

Comparison of GI

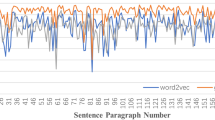

GI reflects the level of grammatical complexity within a text as a parameter of text complexity. The GI in translations demonstrates the translator’s choices in organizing the structure of the translated text. Figure 4 displays the GI of Pipa Xing and its nine translations, both overall and in various stages. The overall GI of each text is linked by a dark line, and the stage-specific variation of GI in each text is represented in distinct columns.

To further examine whether there are significant differences in GI among the ten texts, this study conducts an ANOVA on the data. SPSS 22.0 results show that the data reasonably adheres to a normal distribution, as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test. While the variance homogeneity is not satisfied, the Welch’s analysis of variance is employed. The result of the analysis of variance yields p = 0.005, which falls below the significance threshold of 0.05, indicating statistical significance. This suggests significant differences among the GI levels of the ten texts. As illustrated in Fig. 4, certain translations, namely T3 (5.61), T8 (3.71), T9 (3.16), T7 (3.35), and T6 (3.02) exhibit comparatively higher GI, indicating a higher level of grammatical complexity. In contrast, T10 (2.79), T5 (2.77), T2 (2.65), and T4 (2.4) display lower GI, indicating lower grammatical complexity.

Taxis and hierarchy in Pipa Xing translations

In addition to the ratio of ranking clauses to sentences, grammatical complexity is also influenced by tactic relationships. In the two types of taxis, the hypotactic relation tends to increase the complexity of the text more than the paratactic relation in terms of hierarchy, as hypotaxis involves more layers covering a range of logico-semantic relations (Halliday, 2009; Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014; Lord, 2002; Yu and Wu, 2017).

The distribution of tactic relations in each translation is shown in Table 4. In the ST, the much higher portion of parataxis than hypotaxis fits the general feature of Chinese sentences. According to Wang (1984), the Chinese clause complexes are always paratactic, which may not be connected by grammatical elements explicitly.

Among the five translations with higher GI, the proportion of hypotactic clauses is lower than that of paratactic ones. However, the degree of this difference varies among them. T3 has the lowest proportion of hypotaxis, while T6, T8, T7, and T9 have relatively lower proportions of hypotaxis compared to parataxis. Therefore, though these five translations have higher GI, especially T3, the manifestation of complexity differs. T3’s complexity primarily lies in the ratio of the number of ranking clauses to sentences. Comparatively, T9, T8, T7, and T6 achieve complexity through both: a higher ratio and more complex hypotactic augmentation. Furthermore, T5 and T10 have a higher proportion of hypotactic clauses compared to paratactic ones, displaying the highest level of hierarchy among the nine translations.

To illustrate the different levels of grammatical complexity in each translation, an example from S4 is presented as Example 3 in Fig. 5. While the segment of ST shows a preference for paratactic relation, T3 and T9 (with high GI) and T5 (with low GI) exhibit three different levels of hierarchy in their translations of the same segment. As the trend lines illustrate, the case of T3 consists of a single sentence constituted by 10 ranking clauses, and thus it shows a higher GI (10) than the other two. However, this segment translation is mainly connected by paratactic relations, and thus it contains fewer layers and conveys a lower hierarchy. In contrast, though the case of T9 conveys much a lower GI (3.67) than T3, it contains more hypotactic clauses and is thus more complex in hierarchy. Similarly, although the case of T5 ranks the lowest among the three in terms of GI (2.6), it involves much more hypotactic relations and thus shows the highest complexity in hierarchy.

From the perspective of textual characteristics, paratactic relationships are typically found in the spoken text (e.g., casual conversations), while hypotactic relationships are more commonly associated with written text (e.g., news reports, scientific reports) (Matthiessen, 2002). Moreover, Halliday and Matthiessen (2014) propose the general patterns of text complexity: spoken text tends to have a higher level of GI, and written text often features a higher level of LD.

On this basis, this study finds three different textual characteristics among the nine translations. Firstly, some translations show the typical features of spoken text with high GI and a predominance of paratactic relationships (T3, T8, T7, T9, and T6). Secondly, some translations show the typical features of written text with low GI and a prevalence of hypotactic relationships (T10 and T5). Thirdly, some translations show an intermediate position between typical spoken and written text with low GI and paratactic relationships as the dominant features (T2 and T4).

Logico-semantic relationships and narrativity in Pipa Xing translations

Both taxis and logico-semantic relationships contribute to the construction of sentences as intricate construction patterns, reflecting grammatical complexity. The logico-semantic relations in each text are shown in Fig. 6. The ST and all nine translations exhibit a larger proportion of extension and enhancement relations than elaboration ones but with different emphases. T3, T4, T6, T8, and T9 display more extension, while the ST, T2, T5, T7, and T10 exhibit more enhancement.

Elaboration expands a clause by providing further characterization, specification or description, extension refers to expanding the clauses by the addition of information realized by markers such as addition, contrast, selection, etc., while enhancement involves the modification of clause meaning through markers like time, place, reason, condition, manner, etc. (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014; He and Liu, 2019). In relation to text types, while elaboration is frequent in casual chat and news report, enhancement is more closely related to narrativity, as narratives, such as storytelling genres, often follow a time sequence (Matthiessen, 2002). Therefore, among the nine translations, the emphasis on enhancement relationships in T2, T5, T7, and T10 reflects stronger narrative features.

To illustrate how different translations re-instantiate the ST in terms of logico-semantic relationships, specifically focusing on the enhancement relation, a selected segment from S5 is presented in Example 4 below.

Example 4 Logico-semantic relations in Pipa Xing and its translations

Segment | |||

|---|---|---|---|

T1_ ST | 1 | 我从去年辞帝京, Wǒ cóng qùnián cí dìjīng, I resigned from Imperial Capital last year. | |

+2 | 谪居 Zhéjū banished | ||

+3 | 卧病浔阳城。 wòbìng xún yáng chéng. lying ill in Xunyang City. | ||

1 | xβ | 浔阳地僻 Xún yáng dì pì Xunyang is remote | |

α | 无音乐, wú yīnyuè, no music, | ||

=2 | 终岁不闻丝竹声。 zhōng suì bù wén sīzhú shēng. I don’t hear the sound of silk and bamboo all year round. | ||

1 | xβ | 住近湓江 Zhù jìn pénjiāng live near Penjiang River | |

α | 地低湿, dì dī shī, the ground is low and wet, | ||

=2 | 黄芦苦竹绕宅生。 huáng lú kǔ zhú rào zhái shēng. yellow reeds and bitter bamboos grow around the house. | ||

1 | 其间旦暮闻何物, Qíjiān dàn mù wén hé wù, What did I hear in the morning and evening? | ||

+2 | 杜鹃啼血 dùjuān tí xuè cuckoo cries blood | ||

+3 | 猿哀鸣。 yuán āimíng. the ape whined. | ||

1 | 春江花朝秋月夜, 往往取酒 Chūn jiāng huā zhāo qiū yuè yè, wǎngwǎng qǔ jiǔ On spring river flowers and autumn moonlit nights, people often drink wine | ||

+2 | 还独倾。 hái dú qīng. still leaning alone. | ||

1 | 岂无山歌与村笛, Qǐ wú shān gē yǔ cūn dí, How could there be no folk songs and village flutes? | ||

+2 | 呕哑嘲哳难为听。 ǒu yǎ cháo zhā nánwéi tīng. It’s hard to listen to the vomiting and muttering. | ||

xβ | 今夜闻君琵琶语, Jīnyè wén jūn pípá yǔ, Tonight I hear your pipa music, | ||

α | xβ | 如听仙乐 rú tīng xiān yuè like listening to fairy music | |

α | 耳暂明。 ěr zàn míng. the ears are temporarily clear. | ||

1 | 莫辞 Mò cí Don’t quit | ||

x2 | 更坐 gèng zuò sit down more | ||

+3 | 弹一曲, Tán yì qū, play a song, | ||

+4 | 为君翻作琵琶行。 wèi jūn fān zuò “pípá xíng”. I will translate “Pipa Xing” for you. | ||

T10_ Giles | α | Last year I quitted the Imperial city, | |

xβ | α | banished to this fever-stricken spot, | |

=β | where in its desolation, from year’s end to year’s end, no flute nor guitar is heard. | ||

α | I live by the marshy river-bank, | ||

xβ | surrounded by yellow reeds and stunted bamboos. | ||

1 | Day and night no sounds reach my ears save the blood- stained note of the goatsucker, the gibbon’s mournful wail. | ||

1 | Hill songs I have, and village pipes with their harsh discordant twang. | ||

xγ | But now that I listen to thy lute’s discourse, | ||

α | methinks | ||

‘β | ’tis the music of the Gods. | ||

1 | Prithee sit down awhile | ||

+2 | α | and sing to us yet again, | |

xβ | while I commit thy story to writing. | ||

T6_ Bynner & Kiang | 1 | I came, a year ago, away from the capital | |

+2 | and am now a sick exile here in Kiu-kiang – | ||

+3 | α | and so remote is Kiu-kiang | |

xβ | that I have heard no music, neither string nor bamboo, for a whole year. | ||

1 | My quarters, near the River Town, are low and damp, with bitter reeds and yellow rushes all about the house. | ||

1 | And what is to be heard here, morning and evening? – | ||

1 | The bleeding cry of cuckoos, the whimpering of apes. | ||

1 | On flowery spring mornings and moonlit autumn nights I have often taken wine up | ||

+2 | and drunk it all alone, | ||

+3 | of course there are the mountain songs and the village pipes, | ||

+4 | but they are crude and strident, and grate on my ears. | ||

xβ | And tonight, when I heard you playing your guitar, | ||

α | I felt as if my hearing were bright with fairy-music. | ||

1 | Do not leave us. | ||

1 | Come, | ||

+2 | sit down. | ||

1 | Play for us again. | ||

1 | And I will write a long song concerning a guitar. | ||

T3_ Yang & Yang | 1 | Last year I bade the imperial city farewell; | |

+2 | =β | a demoted official, | |

α | I lay ill in Xunyang; | ||

+3 | Xunyang is a paltry place without any music, | ||

+4 | for one year I heard no wind instruments, no strings. | ||

1 | Now I live on the low, damp flat by the River Pen, | ||

+2 | round my house yellow reeds | ||

+3 | and bitter bamboos grow rife; | ||

+4 | from dawn till dusk I hear no other sounds but the wailing of night-jars and the moaning of apes. | ||

1 | On a day of spring blossoms by the river or moonlit night in autumn I often call for wine | ||

+2 | and drink alone; | ||

+3 | of course, there are rustic songs and village pipes, | ||

+4 | but their shrill discordant notes grate on my ears; | ||

+5 | tonight listening to your lute playing was like hearing fairy music; | ||

=6 | it gladdened my ears. | ||

1 | Don’t refuse, | ||

+2 | but sit down | ||

+3 | and play another tune, | ||

+4 | and I’ll write a Song of the Lute Player for you. | ||

This segment of ST portrays the poet’s melancholy exile in remote Xunyang, evoking feelings of displacement and sorrow that resonate with the pipa player’s life, as narrated in the preceding stage of the poem. The profound sense of desolation is conveyed through the depiction of the bleak setting devoid of music and harsh dwelling conditions, realized in a parallel of the two clause complexes as highlighted in Example 4: “Xún yáng dì pìwú yīnyuè, zhōng suì bù wén sīzhú shēng” (浔阳地僻无音乐, 终岁不闻丝竹声), and “Zhù jìn pénjiāng dì dī shī, huáng lú kǔ zhú rào zhái shēng” (住近湓江地低湿, 黄芦苦竹绕宅生). Each clause complex consists of two clauses in paratactic elaboration, respectively. The primary clause within each clause complex comprises two clauses, with the secondary clause serving as a hypotactic enhancement of the primary one, representing relationships of ‘cause: reason’ and ‘spatiality’. What the hypotactic enhancements underscore is that the absence of music is a consequence of the dwelling’s remoteness, and the poet resides near the Penjiang River, characterized by its low and damp terrain. Furthermore, in the description of the emotional response to the pipa performance, a clause complex with two layers of enhancement is employed. This complex, “Jīnyè wén jūn pípá yǔ, rú tīng xiān yuè ěr zàn míng” (今夜闻君琵琶语, 如听仙乐耳暂明), combines ‘cause: reason’ and ‘manner: comparison’ to reinforce the transformative impact of the melody, which clarifies the poet’s ears and psyche. As a response to this captivating performance, a clause complex construes the poet’s imploration to the player for another piece. This clause complex is characterized by a paratactic enhancement, with the term “gèng” (更) denoting temporal subsequence and continuity.

Overall, enhancement relation in this example of ST serves to weave together the poet’s residence with the starkness and bleak setting devoid of music, the contrasting beauty of the pipa performance, the poet’s emotional transformation, and the plea for the resonating melody in a coherent narrative segment.

In rendering this segment, T10 basically preserved the enhancement relationship presented in the ST. This is particularly evident in the depiction of the poet’s hash-dwelling conditions, his emotional transformation induced by the enchanting melody, and his entreaty to the pipa player. Notably, T10 packs the hash dwelling condition and its backdrop into a single clause complex linked by hypotactic enhancement, thereby elucidating the ‘cause: result’ relationship between the poet’s departure from the Imperial city and their subsequent life of demotion and exile.

Comparatively, T6 opts for more paratactic relations and clause simplexes in its re-instantiation. It utilizes hypotactic enhancement to delineate the temporal relationship between the poet’s hearing of the pipa performance and the subsequent change in mood. Meanwhile, it accentuates the ‘cause: result’ relationship between the remoteness of the poet’s dwelling place and the absence of music.

In contrast, T3 adopts no enhancement relation in its re-instantiation. It mainly utilizes paratactic extension to connect the clauses by introducing additional information. Besides, two elaborating clauses serve to specify the poet’s identity as a demoted official and to comment on the beauty of the pipa performance.

Summary: text complexity and variation of styles in Pipa Xing translations

Through quantitative and exemplar-based comparisons of LD and GI in Pipa Xing and its nine translations, this study arrives at several key findings.

Firstly, in terms of the statistical results of LD and GI, the translations exhibit similar LD levels, and differences in complexity are primarily reflected through GI. Specifically, T3, T8, T7, T9, and T6 have higher level of GI, while T10, T5, T2, and T4 have lower level of GI.

Secondly, by analyzing the distribution of taxis to compare the hierarchical characteristics of each translation, it is found that translations with higher GI (T3, T6, T7, T8, T9) tend to favor paratactic relationships, which exhibit a weaker hierarchical feature, and especially in the case of T3. In contrast, low GI translations, such as T5 and T10, predominantly feature hypotactic relations, indicating a stronger hierarchy.

Finally, by examining the distribution of logico-semantic relationships, the narrativity of each translation is assessed. Versions T2, T5, T7, and T10 exhibit a higher proportion of enhancement relationships, indicating a stronger narrative feature.

In summary, the results of the text complexity, comparison, and textual features of the nine translations of Pipa Xing are presented in Table 5. It is shown that T3, T8, T7, T9, and T6 exhibit features of spoken text, T10 and T5 exhibit features of written text, and T2 and T4 exhibit characteristics that lie between spoken and written text. Meanwhile, T2, T5, T7, and T10 demonstrate stronger narrativity.

Discussion: an individuation perspective

Translation is a guided creation of meaning (Halliday, 1992), influenced and restrained by a complex interplay and negotiation among various factors such as the context of translation, the original text, ideology, prevailing literary system, cultural disparities, and so on. While the translator’s subjectivity drives the process of translation under such restraints, the translation product reflects the translator’s identity, choices, and creations made in pursuit of translation goals.

From an individuation perspective, the generation of a translation is influenced by the translator’s individuation process: the translator employs meaning resources allocated from the cultural reservoir to the individual repertoire to recognize the author’s meaning resources realized in the ST and then utilizes meaning resources from the individual repertoire to realize the translation. This process of recognition and realization is not only subject to the allocation of meaning resources from the sociocultural reservoir to the translator’s repertoire, but also driven by the translator’s role in establishing affiliation with the target readership. While the cultural disparities, ideology, and prevailing literary system construct and define the reservoir of culture that a translator belongs to, the translator’s master identity, community affiliations, and the target readership on this hierarchy of individuation manipulates the translator’s activity, which is ultimately manifested in the selection of lexicogrammatical resources at the language level, resulting in different translation styles.

This section explores factors influencing translators’ choices by foregrounding translator identity along the bidirectional trajectory of individuation (Martin, 2010; Martin et al., 2013). In Section “Data and research methods”, we categorized the translators of Pipa Xing into Chinese translators, British or American translators and Sino-Western collaborative translators by adopting nationality as a prime parameter. Incorporated with the era as another feature of master identity, translators’ professional affiliations and aligned target readerships at the subculture/community level are examined as parameters influencing lexicogrammatical choices shaping translation styles.

Chinese translators

Chinese translators Xu Yuanchong’s and Lin Yutang’s re-instantiation exhibit spoken-written hybridity with relatively low grammatical intricacy. However, distinct professional trajectories and epochal positioning engendered unique translation priorities.

A renowned trilingual Chinese translator, Xu Yuanchong (1921–2021) produced over 50 interlingual translations in his life. Educated at Southwest Associated University, Tsinghua University and the University of Paris in Chinese and Western literatures since 1940s, Xu became well-versed in classical Chinese literature, English language and literature, world history and French and European literature (Xu, 2017, 2021). He started his literary translation career in 1956, yielding celebrated translations from 1979 onwards when working as a Peking University professor (Zhang, 2022).

Amid China’s reforming and opening-up since the late 1970s, Xu strived to catalyze domestic advancement and contest cultural inferiority complexes through translation. Xu articulated his mission to “change some Chinese people’s sense of inferiority” and reinforced that “China is not inferior to other countries in translation theory or practice, rather it can be even superior in some respects” (Xu and Xu, 2019, pp. 61-62). He harbored acute pride in Chinese culture, targeting translation readership amongst Chinese and Western readers while competing with sinologists’ translations (Zhang, 2022; Zhang, 2022). Xu chose rhymed translation upholding the form of classical poems Pipa Xing, whilst accentuating intrinsic narrative dimensions for Chinese and foreign scholarly readers.

Lin Yutang (1895–1976), an eminent Chinese bilingual writer-translator, lived through the early 1900s nadir in China’s global image. Lin studied at St. John’s University, Harvard University and Leipzig University in the 1920s. As a globally celebrated writer, Lin was redressing the Sinophobic misconceptions through his works like My Country and My People and The Art of Living, the acclaimed elucidations of Chinese culture for Western readers (Feng, 2022). Meanwhile, as a renowned translator, Lin produced translated works through “transcreation” and “cultural transformation in translation”, optimizing the external communication of China’s cultural ethos to Western lay readership (Bian, 2005, pp. 47–50). Lin’s translation of ancient Chinese poetry typified such cultural translation and domestication for English readers – his core aligned readership (Lin, 1933; 1960).

Lin selected Pipa Xing as a case of the “conflict between the practical and the poetic vision of life” possessed by the educated class of Chinese, “the very conflict which is unknown to the West” (Lin, 1960, pp. 17–20). It is a conflict between the outward success and the poetic vision of life associated with simple joy of living. Contextualized as encapsulating this inherent conflict, Lin’s Pipa Xing re-instantiation employed prose and reduced narrative feature to recount the poet’s beautified encounter with the pipa player saturated with empathy and sorrow for secular failures, for a better understanding by the aligned readers.

Ultimately, while both versions privilege accessibility with low grammatical complexity, Xu and Lin’s translation choices remained indelibly shaped by their cultural and community identities and alignment goals, whether strictly upholding the ST style and substance for readers or facilitating cross-cultural understanding. Thereby each Chinese translator forged distinct stylistic priorities based on their cultural positioning and intended reader communication.

British or American translators

Cranmer-Byng, Watson, and Gaunt’s translations all exhibit features of spoken style with high GI and reduced narrative quality in the latter two, while Giles’ translation showcases characteristics of written one with high narrative feature. These variations are deeply influenced by their diverse cultural positioning, community identity and intended readership alignments.

Herbert Giles (1845–1935), doyen of British sinology since the 19th century, officiated in the Chinese customs service for over 25 years, cementing an intuitive sociocultural comprehension and deepening his proficiency in Chinese language and literature. Giles was among the representatives sharing the belongingness to an impressive “group of hyphenated missionary and consul-scholars who, after starting out in the grand tradition of the British and American amateur scholar, went on to become professional or semi-professional sinologists” (Girardot, 2002, p. 7). As Cambridge University’s Professor of Sinology, Giles’ dissatisfaction with arbitrary renderings of classical Chinese poetry led him to promote systematic transmission to Western academia as an intercultural pioneer. He criticized that the ancient Chinese poetry that shines brightly in China like a precious gem had been “concealed, beyond the pry of vulgar eyes” due to their lack of understanding of the language, and proposed that only patient scholars can unlock this brilliance amid the labyrinthine guidance of language. (Giles, 1898, p. 0; Ge, 2015, pp. 207-208). His academic path molded his re-instantiation of ancient Chinese poems. Accordingly, his Pipa Xing translation exhibits a formal, narratively intricate written style befitting his identity as a sinologist seeking for affiliations within Anglo-European sinological circles.

Alternatively, Gaunt’s late 19th century missionary-translator cohort in China constituted seminal conduits between Chinese and British civilizations. Similar with the diplomat-sinologists, this group constituted a distinctive cultural community marked by a confluence of tensions arising from Sino-British interactions, reflecting the intricate dynamics of collision, contact, and integration between British civilization and Chinese culture. The role of missionary-translator was characterized by a dual mission: “the sacred endeavor to convert the Oriental populace to Catholicism” and “a parallel aspiration to imbue the Western world with the tenets of Oriental philosophy”. As Chen (2008, p. 35) comments, “in addition to transmitting the Renaissance humanistic ethos to the East, they played a pioneering role in promoting Chinese culture within the British context”. This multifaceted engagement underscores their significance as historical actors intricately positioned at the nexus of diverse cultural and ideological currents, facilitating a nuanced understanding of the interplay between China and Britain during this epoch. Rather than the alignment with British sinolocial academia, Gaunt sought resonance with English general readers to offer “some little pleasure therefrom” and “a glimpse of the working of the Chinese mind a thousand years ago” (Gaunt, 1919, p. 5). Hence, his re-instantiation of Pipa Xing leaned more towards colloquial with low narrative features in its style.

During the early 20th century, there was a notable diffusion of ancient Chinese classics from the sinology academia to a broader audience, with a distinct community emerging to contribute significantly through the retranslation of English versions of ancient Chinese poetry. Diverging from the British diplomat-sinologist and missionary-translator community, which possessed prolonged residence in China and an intuitive comprehension of Chinese culture, society, language and literature, this particular community comprised poets and writers characterized by remarkable aesthetic proficiency but a “limited or even no knowledge of Chinese language or culture” (Jiang, 2018, p. 13). Among these contributors, Cranmer-Byng stood out for his exceptional contributions.

Cranmer-Byng (1872–1945) was a British poet in the early 20th century and the first person to actively promote Tang poetry in the Western world as a creative writer (Jiang, 2013). Deviating from the scholastic tradition represented by Giles, Cranmer-Byng contested the scholastic pattern of translation, criticizing it as precise yet lacking in agility. Cranmer-Byng opted to rework Giles’ translations through the role of “a literary man”, who “should stand forth and claim his share in the revelation of truth and beauty from other lands and peoples whom our invincible European ignorance has taught us to despise” (Cranmer-Byng, 1908, pp. 13-14). By adapting Giles’ translation of Pipa Xing, Cranmer-Byng retained its narrative essence while elevating a more colloquial style, catering to a readership aligned with poets and the general English public instead of sinology specialists.

Echoing such priorities, modern American sinologist-translator Burton Watson (1925–2017) shared similarity in community identity with Giles, albeit within a distinct cultural context. In contrast to the European sinological tradition, American sinology is characterized by interdisciplinarity and utilitarian purposes, aligning with military defense, foreign policy, expansion, and related concerns (Jiang, 2018).

Influenced by cultural and diplomatic ideologies in America after World War II, Columbia University Press responded to the dearth of English materials for undergraduate Chinese studies courses (Liu and Xia, 2022). In collaboration with this initiative, Watson played a pivotal role in translating Chinese classics, specifically rendering them to the needs of a broader English readers, particularly American college students seeking an understanding of Chinese culture. Watson’s re-instantiation of Pipa Xing, marked by foreignization and free verse, adopted a more colloquial style. This approach aligns with the broader educational objective of making Chinese cultural materials accessible to a non-specialist readership, as an exemplar elucidating the intersection of linguistic and cultural considerations in the transmission of ancient Chinese literature within the American academic milieu.

Sino-western collaborative translators

With this collaborative category, the translation process entails Chinese translators initially performing interlingual translation, followed by discussions with Western translators and subsequent intralingual translation or adaptation (Bynner, 1929; Zhang, 1988; Yang, 2007). The similarities and variations in complexity and narrative features across the three works suggest a delicate balance in considerations of cultural positioning, socio-historical impact, scholarly belongingness, and alignment with target readers.

Witter Bynner (1881–1968), a notable American poet critical of conventional norms, was among the pioneers who introduced foreign influences into America’s emerging literary landscape, contributing to its post-colonial cultural renewal (Quartermain, 1987). In contrast with the pragmatic focus on “China studies” in American sinological academia, this community labored on translating the ancient Chinese poetry amidst the avant-garde “New Poetry Movement”, profoundly inspiring generations of poets and readers alike (Zhong, 2003; Jiang, 2018). On this ground, poet Bynner engaged with fellow poets and a broader readership, actively shaping the distinctive features of the nation’s burgeoning literature through the translation of ancient Chinese poems.

Kiang (1883–1954), a Chinese scholar well educated in traditional Chinese classics and teacher at University of California, Berkeley, collaborated with Bynner in response to the calls for American Chinese to facilitate English translations of ancient Chinese poetry. With literary mastery and endeavor to align general English readers, Kiang chose and recommend to Bynner the widely circulated Three Hundred T’ang Poems as the ST, appreciated by both poets and the general public (Kiang, 1929, p. xxvii). This choice was driven by his purpose to enhance Western comprehension of the essence of Chinese culture (Watson, 1978). Ultimately, Bynner and Kiang’s joint translation adopts a colloquial style streamlining Pipa Xing’s narrative feature to resonate with specialist poets and general readers amid prevailing Orientalist literary mores.

Subsequent to Bynner and Kiang’s era, Yang Xianyi (1915–2009) and Gladys Yang (1919–1999) were amongst the most prolific translators of Chinese classics since the 1950s. Educated in traditional Chinese classics and English from youth, Yang pursued advanced studies in Greek, Latin and classical literatures at Oxford University in the 1930s, where he befriended his future wife, Gladys Tayler (Yang, 2002). Born to British missionaries in China, Gladys developed compassion for the Chinese people amid poverty and war. At Oxford University, she blazed trails as the pioneer graduate in the Honor School in Chinese. In the 1940s, the Yangs returned to war-torn China, serving as professional translators in state and academic institutions. In the 1980s, Yang helmed Chinese Literature journal and the “Panda Books” series - inspired by the British “Penguin” series - which encompassed modern and classical Chinese works to spotlight Chinese literature overseas (Yang, 2012).

Regarding their professional allegiances, translating for quasi-state entities instilled a mission “to disseminate Chinese heritage abroad and reconnect with Western readerships” (Xin, 2020, p. 6). However, divergent cultural socialization and identities engendered distinct preferences in original text selection and translation approaches requiring compromise. For instance, Yang’s Chinese upbringing and classical education precipitated his propensity for ancient classics (Wang and Li, 2020), while Gladys preferred contemporary and women’s works due to affinities as a foreign-born woman (Wang, 2018). Regarding translation approaches, Yang favored foreignizing faithfulness while Gladys prioritized reader-centric fluency (Henderson, 1981).

Nevertheless, their Pipa Xing translation reveals joint accommodation for reader comprehension, and domestication was exemplified through lexicogrammatical choices. For example, they selected “nightjar” instead of “cuckoo” in re-instantiating the allusion “杜鹃啼血” (literally translated as “cuckoo cries blood”), signifying anguish and sadness for national destruction. Since while “cuckoo” denotatively conveys mourning, its additional connotation of stupidity would jar with the source allusion. Additionally, adopting a free verse and spoken language style aligned with contemporary English readers’ habitus. Overall, notwithstanding cultural and individual divergence, their collaborative translation of Pipa Xing was principally oriented towards comprehensibility and resonance with general English readers.

In contrast to the Yangs as well as Bynner and Kiang whose re-instantiation were oriented to the general Western readers, Zhang Tingchen and Bruce Wilson’s Pipa Xing translation displays a distinct style of written language and with preservation of narrative feature. This variation is indicative of their scholarly allegiances and multifaceted readership they sought to align.

Zhang’s academic journey encompassed Shanghai International Studies University, Fudan University, and Columbia University in American and Comparative Literature. Bruce Wilson has been an English professor at St. Mary’s College of Maryland, and directed the Fudan - St. Mary’s Exchange Program during the 1980s to 1990s. Despite their divergent cultural backgrounds, a shared academic commitment and expertise in literary and comparative studies, particularly in ancient Chinese poetry, underpinned their collaboration. They not only targeted a general English readership, but also aimed to captivate the “comparativists and students of Chinese language in the West”, as well as “Chinese readers interested in English poetry and in translation” (Wilson, 1988, p. 19). Consequently, their re-instantiating has to negotiate between their scholarly identity and demands of varied readership interest across cultural and proficient bounds. In comparison with the other two collaborative versions adopting spoken-language style streamlining narrative for Western publics, Zhang and Wilson’s scholarly rendering maintains a written style in high narrative to resonate with academic readers in both cultures fascinated by the source legend’s poetic form and cross-cultural interpretation.

Conclusion

This study has examined the translation styles of Pipa Xing from the perspective of text complexity and elucidated the variation in translation styles from an individuation perspective. By employing both quantitative and qualitative analyses, we analyzed and compared the LD and GI of nine English translations of Pipa Xing. The results showed that these translations exhibited similarities in LD but differences in GI, reflecting varying complexity, hierarchy, and narrativity.

These differences are explained from the perspective of the translator individuation process. The allocation of sociocultural meaning resources to translator identities constrains the resources they can access, which affects the meaning configuration realized in each translation based on their multi-facet identities. Furthermore, target readerships influence translator affiliation choices. From cultural interaction and communication between the original authorship and target readership to specific lexicogrammatical choices, translators navigate their roles in the relationship between the two and leverage their interactivity. The allocation of meaning resources and establishment of affiliation relationships follow different paths for each translator, ultimately manifesting as stylistic differences across translations. Therefore, based on Martin et al.’s individuation model (2013, p. 490) and the study of translations of Pipa Xing, we outline the translator’s individualization process as shown in Fig. 7. This model provides a visual representation of how broader cultural and social context imprints upon and permeates through the translator’s identities and affiliations at different scales to their individual repertoire, in which lexicogrammatical choices are mobilized to undergird stylistic diversity in translation.

This diagram illustrates the model of the translator’s individuation process. The two diagonal clines symbolize the dual pathways within the translator’s individuation process. The two arrows at the bottom signify the translator’s role as a mediator between the original author and the target reader. The two arrows at the top depict the convergence of the translator’s cultural reservoir, where the semiotic resources of the source culture merge with those of the target culture.

In summary, translator choices are not arbitrary but rather deeply rooted in the sociocultural context, in which translators play an active role. The individuation perspective provides a pathway for elucidating the translator’s role and offers a new lens for exploring issues of sociocultural factors, subjectivity, and intersubjectivity during translation.

References

Bai J (2019) Pipa Xing. In: Heng Tang Tui Shi (ed.) Tang shi san bai shou (唐诗三百首). The North Literature and Art Publishing House, Ha’erbin, p 78–80. 816/

Barbaresi ML (2003) Complexity in language and text. Edizioni Plus, Pisa

Bian J (2005) Rethinking Lin Yutang’s cultural transformation in translation. Shanghai J Translation 1:47–50

Biber D (1992) On the complexity of discourse complexity: A multidimensional analysis. Discourse Process 15(2):133–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/01638539209544806

Bourdieu P (1977) Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Bourdieu P (1991) Language and symbolic power. Polity Press, Cambridge

Bynner HW (1929) Poetry and culture. In: Bynner HW, Kiang KH (ed.) The jade mountain: a Chinese anthology - being three hundred poems of the T’ang dynasty 618-906. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, p xiii–xix

Bynner HW, Kiang K (ed.) (1929) The jade mountain: a Chinese anthology - being three hundred poems of the Tang Dynasty 618-906. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, pp 125-130

Chang C (2018) Modeling translation as re-instantiation. Perspectives 26(2):166–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/0907676X.2017.1369553

Chen Y (1950) Evidence from Baixiangshan Pipa Xing Notes. Lingnan J 10(2):1–11. http://commons.ln.edu.hk/ljcs_1929/vol10/iss2/1

Chen Y (2008) On the characteristics of the various stages of Sinology in England: as seen from the viewpoint of research in Classical Chinese Literature. Newsl Res Chin Stud 27(3):34–47

Cranmer-Byng LA (1908) The book of odes (Shi King): the classic of Confucius. John Murray, London

Cranmer-Byng LA (1915) Lute of jade: selections from the classical poets of China. E. P. Dutton and Company, New York, p 75–79

Fang Z (2006) The language demands of science reading in middle school. Int J Sci Educ 28(5):491–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690500339092

Feng Q (2022) Selections of Lin Yutang’s translation. Zhejiang. University Press, Hangzhou

Gaunt T (1919) A little garland from Cathay. Presbyterian Mission Press, Shanghai, p 12–18

Ge G (2015) History of Sino-English literary exchange: from the fourteenth to the mid-twentieth century. Wanjuan Lou, Taipei

Giles HA (1884) Gems of Chinese Literature. Bernard Quaritch, London, p 157–160

Giles HA (1898) Chinese poetry in English verse. Bernard Quaritch, London

Girardot NJ (2002) The Victorian translation of China: James Legges oriental pilgrimage. University of California Press, Berkeley

Halliday MAK (1989) Spoken and written Language. Oxford University Press, New York

Halliday MAK (1992) Language theory and translation practice. Riv internazionale di Tech della traduzione 0:15–25

Halliday MAK (2009) Method – techniques – problems. In: Halliday MAK, Webster JJ (eds.) Continuum companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics. Continuum, London, p 59–88

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen CMIM (1999) Construing experience through meaning: a language-based approach to cognition. Cassell, London

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen CMIM (2014) Halliday’s introduction to unctional Grammar, 4th edn. Routledge, London

Halliday MAK (2003) On language in relation to the evolution of human consciousness. In: Webster JJ (ed.) On language and linguistics. The collected works of MAK Halliday, vol 3. Continuum, London, p 390–432

He W, Guo X (2020) Complex Features of Language System and Realizations of Textual Metafunction. Contemp Rhetor 1:39–49

He W, Liu J (2019) A contrastive study of the logico-semantic relations and their representations between English and Chinese Clauses. J Univ Sci Technol Beijing 35(2):1–17

He W, Wang M (2019) A contrastive study of English and Chinese clause structures. J SJTU(Philos Soc Sci) 27:116–137

Henderson KR (1981) The wrong side of a Turkish tapestry. Chin Translator J 1:5–9

Huang G, Liu Y (2015) Functional linguistics research on language complexity: comparison of the difficulty level between the original and abbreviated version of Alice’s Adventures in Adventures. Foreign Lang Educ 36(2):1–7

Izquierdo IG, Borillo JM (2000) The degree of grammatical complexity in literary texts as a translation problem. In: Beeby A, Ensinger D, Presas M (eds) Investigating translation: selected Papers from the 4th international congress on translation. John Benjamins Publishing, London, p 65–76

Jian C (1994) A brief introduction to the study of Bai Juyi in China over the past eighty years (中国における八十年来の白居易研究略説). In: Tsuguo Ota (ed) Issues surrounding the acceptance of Bai Juyi’s poetry (白詩受容を繞る諸問題). Benseisha Co., Ltd., Tokyo, p 72–92

Jiang L (2013) A history of Western appreciation of English-translated Tang Poetry. Xueyuan Press, Beijing

Jiang L (2018) A history of Western appreciation of English-translated Tang Poetry. Springer, New York

Kiang K (1929) Chinese poetry. In: Bynner HW, Kiang K (ed.) The jade mountain: a Chinese anthology - being three hundred poems of the Tang Dynasty 618-906. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, p xxi–xxxvii

Lassen I (2003) Accessibility and acceptability in technical manuals: a survey of style and grammatical metaphor. John Benjamins Publishing, London

Lefevere A (1992) Translation, rewriting and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge, London

Lefevere A (2017) Translation, rewriting and the manipulation of literary fame. Routledge, London

Lin Y (1960) The importance of understanding: translations from the Chinese. The World Publishing Company, Cleveland, p 315–318

Lin Y (1933) On Translation. In: Wu S. (ed.) On Translation. Guanghua Shu Ju, pp 1-17

Liu S, Xia D (2022) European and American experience in overseas publishing and dissemination of Chinese culture – a case study of Columbia University Press. Publ J 30(4):99–105

Lord C (2002) Are subordinate clauses more difficult? In: Bybee J (ed.) Complex sentences in grammar and discourse essays in honor of Sandra A. Thompson. John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam, p 223–234

Martin JR (2009) Realisation, instantiation and individuation: Some thoughts on identity in Youth Justice Conferencing. DELTA: Docção de Estudos em Linguistica Teorica e Aplicada 25:549–583. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-44502009000300002

Martin JR (2010) Semantic variation: modelling realisation, instantiation and individuation in social semiosis. In: Bednarek M, Martin JR (eds.) New discourse on language: functional perspectives on multimodality, identity, and affiliation. Continuum, London, p 1–34

Martin JR (2008) Innocence: realisation, instantiation and individuation in a Botswanan Town. In: Mahboob A, Knight N (eds.) Questioning Linguistics. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle, p 32–76

Martin JR, Quiroz B (2021) Functional language typology: systemic functional perspectives. In: Kim M, Munday J, Wang Z, Wang P (eds.) Systemic Functional Linguistics and Translation Studies. Bloomsbury, London, p 7–33

Martin JR, Rose D (2008) Genre relations: mapping culture. Equinox, London

Martin JR, Zappavigna M, Dwyer P, Cléirigh C (2013) Users in uses of language: embodied identity in Youth Justice Conferencing. Text Talk 33(4-5):467–496. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2013-0022

Matthiessen CMIM (1995) Lexicogrammatical cartography English systems. International Language Sciences Publishers, Tokyo

Matthiessen CMIM (2002) Combining clauses into clause complexes: a multi-faceted view. In: Bybee J (ed.) Complex sentences in grammar and discourse essays in honor of Sandra A. Thompson. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam, p 235–319

Matthiessen CMIM (2001) The environment of translation. In: Steiner E, Yallop C (eds.) Exploring translation and multilingual text production: beyond content. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin, p 41–124

Matthiessen CMIM, Wang B, Ma Y, Mwinlaaru IN (2022) Systemic functional insights on language and linguistics. Springer, Singapore

Nord C (2018) Translation as a purposeful activity – functionalist approaches explained, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Quartermain P (1987) American poets 1880-1945, 3rd series. Gale Research Company, Detroit, p 13–21

Rexroth K (1966) The collected shorter poems of Kenneth Rexroth. New Directions Publishing Corporation, New York

Sauro S, Smith B (2010) Investigating L2 performance in text chat. Appl Linguist 31(4):554–577. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amq007

Schäffner C, Holmes HK (1995) Cultural functions of translation. Multilingual Matters. Ltd., Clevedon

Venuti L (1992) Rethinking translation: discourse, subjectivity, ideology. Routledge, London

Venuti L (1998) The scandals of translation: towards an ethics of difference. Routledge, London

Venuti L (2008) The translator’s invisibility: a history of translation, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Venuti L (2021) The translation studies reader (4th ed.). Routledge, London

Wang B, Li W (2020) A comparative analysis of the translators’ habitus of Yang Xianyi and Gladys. Fudan Forum Foreign Lang Lit 1:141–146

Wang L (1984) Chinese Grammar Theory. Shandong. Education Press, Jinan

Wang L (2015) An Outline of Chinese Grammar. Zhonghua Book Company, Beijing

Wang P (2021) Instantiation and individuation in Buddhist scripture translation: a cross-comparison of the Sanskrit ST and English and Chinese TTs of the Heart Sutra. Lang, Context Text 3(2):227–246. https://doi.org/10.1075/langct.20004.wan

Wang Y (2018) Studies on English translations of Chinese fiction. Foreign Language Teaching and Research Press, Beijing

Watson B (1984) The Columbia book of Chinese poetry: from early times to the thirteenth century. Columbia University Press, New York, p 249–252

Watson B (1978) Introduction to The Jade Mountain. In: Kraft J (ed.) The Chinese translations: the works of Witter Bynner. Farrar, Straus, Giroux, New York, p 13–32

Wilson B (1988) Preface. In: Zhang T, Wilson B (eds.) One Hundred Tang Poems. The Commercial Press Ltd., Hong Kong, p 13–19

Wu C (2009) Corpus based research. In: Halliday MAK, Webster JJ (eds.) Continuum companion to Systemic Functional Linguistics. Continuum, London, p 128–142

Xin H (2020) Introduction. In: Xin H (ed.) Representative translation database of Chinese translators: Yang Xianyi and Gladys. Zhejiang University Press, Hangzhou, p 1–26

Xu Y (1994) Song of the Immortals: an anthology of classical Chinese poetry. New World Press, Beijing, p 118–121

Xu Y (2017) Dreams and Reality – Xu Yuanchong’s Autobiography. Henan Literature and Art Publishing House, Zhengzhou

Xu Y (2021) Xu Yuanchon: the forever Southwest Associated University. Jiangsu Phoenix Literature and Art Publishing Ltd., Nanjing

Xu Y, Xu J (2019) Translation as the “art of beautification”. In: Xu J (ed.) Dialogues on the Theory and Practice of Literary Translation. Routledge, London, p 61–74

Yang X (2012) White Tiger: An Autobiography of Yang Xianyi. The Chinese University of Hongkong Press, Hong Kong

Yang X, Yang G (1984) Poetry and prose of the Tang and Song. Chinese Literature Press, Beijing, p 125–129

Yang X (2007) Me and the English translation of “A Dream of Red Mansions”. In: Zheng L (ed.) One book and one World, vol2. Kunlun Publishing House, Beijing, p 1–3

Yu H, Wu C (2017) Text complexity as an indicator of translational style: A case study. Linguist Hum Sci 13(1-2):179–200. https://doi.org/10.1558/lhs.35709

Zhang T, Wilson B (1988) One Hundred Tang Poems. The Commercial Press Ltd., Hong Kong, p 315–318

Zhang T (1988) Preface. In: Zhang T, Wilson B (ed.) One hundred Tang poems. The Commercial Press Ltd., Hong Kong, p 1–12

Zhang X (2022) A study on the influence of Ancient Chinese Cultural Classics abroad in the Twentieth Century. Springer, Singapore, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-7936-0

Zhang Z (2022) On Xu Yuanchong’s translation practice and theory: contributions and limitations. Chin Transl J 4:92–97

Zhong L (2003) American Poetry and the Chinese Dream: Chinese Cultural Model in Modern American Poetry. Guangxi Normal University Press, Guilin

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions