Abstract

Amidst the diverse cultural and religious tapestry of Indonesia, Buddhism holds a prominent position as a major faith. Within the context of multiculturalism and generational shifts, this study explores the evolving identification of young Chinese Indonesians with Buddhism. This research addresses the existing knowledge gap by investigating the intricate interplay of historical, cultural, and religious elements that help shape young Chinese Indonesians’ identification with Buddhism. By conducting a thorough analysis of quantitative data gathered from young Chinese Indonesians through a survey, this study investigates six dimensions of identification with Buddhism. This examination considers variables such as age, family background, and regional disparities. Furthermore, to obtain deeper insights and support the quantitative findings, the researchers conducted semistructured interviews to gather qualitative data. The findings reveal the characteristics of young Chinese Indonesians’ identification with Buddhism. First, there are significant variations in identification levels across regions, with relatively lower levels in Java and higher levels in other archipelagos. Personal factors, such as parents’ occupations, also influence individuals’ degree of identification with Buddhism. Second, today’s Chinese Indonesian youth maintain their identification with Buddhism through family ties despite overall intergenerational decline. The participants also show a keen interest in modern religious symbols, dissemination methods, and content. Third, the Buddhist identity of Chinese Indonesian youth transcends traditional values and cultural content, reflecting characteristics of multiculturalism and cultural blending. They not only appreciate various aspects of local culture but also incorporate Buddhist values and symbols into the mainstream of globally shared culture, creating a more extensive and modern collective cultural identity. Unveiling the factors that shape Buddhist identification among Chinese Indonesian youths has implications for fostering intercultural and intergenerational cohesion. The insights derived from this research can contribute to the design of effective strategies aimed at advancing the broader goal of cultural harmony and social unity in Indonesia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of Buddhism in Indonesia is closely connected to that in countries such as China, Thailand, and Myanmar and is entwined with indigenous history and culture, thus giving it distinctive hybrid characteristics (Chia 2018). Buddhism, once the religion of ancient Indonesia, is commonly considered a Chinese religion. This perception has its roots in the reintroduction of Buddhism by the Chinese in early twentieth-century Indonesia, after a period of dormancy lasting several hundred years. The arrival of Dutch theosophists in Indonesia played a pivotal role in reigniting interest in Buddhism, but the majority of Buddhists remained of ethnic Chinese descent, resulting in a strong influence of Chinese culture on modern Buddhist practices.

After gaining independence, as a part of its nation-building project, Indonesia started to Indonesianize its Chinese citizens (Setefanus 2019). This Indonesianization covered the political, social, cultural, and religious spheres. This effort was intensified under the New Order regime, which sought to diminish the influence of Chinese cultural traditions in Buddhism through rationalization and the promotion of a modern, nationalist form of the religion. Chinese Indonesians were encouraged to either forsake their traditional religions, such as Confucianism, Taoism, and Chinese Buddhism, or integrate into a more Indonesianized form of Buddhism that minimized its traditional Chinese influences (Setefanus 2019).

However, this program of “purifying” Chinese Indonesians came to an end with the fall of the New Order in 1998, which also heralded a resurgence of Chinese tradition and culture. Rituals and practices from Chinese traditions, especially religious beliefs traditionally associated with the Chinese, such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism, began to re-emerge, and Chinese Buddhism experienced a resurgence. Chinese Buddhism started to develop again. Looking at history, it can be seen that in the environment in which young Chinese Indonesians are brought up, elements from various religious traditions such as Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism (Setefanus 2019), as well as Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Catholicism (Saragih 2019), are intermingled. These religions, including their practices, have inevitably blended with certain Chinese cultural factors and traditional rituals. This has led to a unique perspective on identification with Buddhism and culture, distinguishing these individuals from their ancestors and parents.

Chinese Indonesian youth constitute a demographic grappling with the intricacies of cultural heritage and societal integration. These youth represent the future, and their alignment with Buddhism and the development of Buddhist culture are pivotal for the expansion of the religion and the Buddhist community. Previous research has often approached identification with Buddhism and developmental processes from an ethnographic perspective, providing case studies or narrative accounts. While these qualitative approaches have undoubtedly enriched our understanding of the subjective experiences and cultural nuances involved in identification with Buddhism, a critical gap persists—there is a lack of robust quantitative analysis of the identification trends among young individuals. This gap not only hampers the comprehensiveness of our insights but also impedes our ability to discern broader patterns and variations in the identification with Buddhism.

The reliance on qualitative methodologies, although valuable in capturing the depth of individual experiences, may fall short of providing a holistic view of the broader demographic landscape. The absence of rigorous quantitative analyses limits our capacity to draw statistically significant conclusions, potentially obscuring vital correlations and trends that could inform targeted interventions and policy recommendations. Furthermore, a solely ethnographic approach may inadvertently perpetuate stereotypes or overemphasize isolated narratives, hindering a nuanced understanding of the complex factors influencing identification with Buddhism among young demographics.

Therefore, to address this gap, the researchers employ a mixed-methods approach grounded in quantitative analysis to understand the current level of and factors influencing identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation. This research employs a comprehensive mixed-methods approach to examine the characteristics and developmental trends of identification with Buddhism among the younger generation of Chinese Indonesians. The primary objective is to scrutinize the dimensions of identification with Buddhism, focusing on generational transition features. By investigating factors such as education, parental occupation, and age, the study aims to unveil the nuanced evolution of Buddhist identification across generations. Additionally, the research explores modern aspects of identification with Buddhism, including geographic distribution patterns and family-centric transmission methods. Through discussions on the integration of Buddhist spirituality with contemporary society and its resonance with the spiritual lives of modern youth, the study seeks to provide a deeper understanding of the evolution of identification with Buddhism in a multicultural context. Ultimately, the research aims to offer insights into the preservation and development of the religious and cultural identity of the Chinese Indonesian population.

Literature review

Identity and religious identification development among Chinese Indonesians

The intersection of identity and the development of religious identification among Chinese Indonesians represents a dynamic and complex area of scholarly inquiry, reflective of the multifaceted nature of this demographic within the Indonesian context. As Chinese Indonesians continue to grapple with the intricacies of cultural heritage and societal integration, understanding the evolution of their religious identity is pivotal.

To comprehend the contemporary dynamics of religious identification among Chinese Indonesians, it is crucial to contextualize these dynamics against the historical backdrop of Indonesia. The community’s historical trajectory, marked by periods of marginalization and shifting policies, has significantly shaped their cultural identity (Hoon 2006). The synthesis of Chinese cultural heritage with Indonesian societal expectations has created a unique space for the negotiation of identity, encompassing linguistic, ethnic, and religious dimensions (Hoon 2006).

Throughout Indonesia’s history, the religious identity of the Chinese Indonesian community has undergone significant transformations. During the seventeenth century, the religious identity of Chinese Indonesians frequently entailed a fusion of Taoist and Confucian ideologies, amalgamating with traditional Chinese faith. By the late nineteenth century, the arrival of Dutch theosophists sparked a revival of Buddhism, further nurturing the religious beliefs of the Chinese community (Setefanus 2011). During this period, Buddhism as a whole was notably influenced by Mahāyāna Buddhism. Subsequently, there was a gradual detachment from Chinese influences, with a growing emphasis on Buddhist doctrines. This shift was particularly pronounced during President Suharto’s “New Order” regime, finding support among Chinese Indonesian Buddhists who aimed to “purify” Buddhism of its “nonreligious elements” and dissociate it from the societal stigma of being a “Chinese religion” (Setefanus 2019). This period emphasized the adoption of Indonesian names, the use of the Indonesian language, and the downplaying of one’s Chinese identity. Religion remained one of the few symbols that Chinese Indonesians could use to express their identity, as other traditional practices were restricted or even prohibited, with transmission confined to family settings. As a result, administrative actions mandating religious beliefs also led many individuals who had previously adhered to other religions to be categorized as Buddhists (Setefanus 2011). The downfall of Suharto’s regime in 1998 initiated political reforms, creating new opportunities for the cultural identity of Chinese Indonesians. Indonesian society gradually embraced multiculturalism, which brought new prospects for the religious identity of Chinese Indonesians (Suryadinata 2008; Chin and Tanasaldy 2019). For instance, individuals were once again allowed to chant in Chinese, and some traditional cultural ceremonies that had been prohibited were reauthorized (Hoon 2006; Setefanus 2019).

Owing to diverse factors such as politics, culture, intermarriage, and other influences, the transformation of religious identity among Buddhists and adherents of other religions was not uncommon. For example, throughout the twentieth century, Chinese religious and cultural practices were banned and severely persecuted in Indonesia. As a result, a considerable number of Chinese Indonesians opted to attend private schools, many of which are affiliated with either Catholic or Protestant faiths. Consequently, a significant portion of Chinese Indonesians became acquainted with these religions and subsequently chose to embrace them (Brazier 2006). According to the 2010 census estimate, 4.7% of the Chinese Indonesian population at the time adhered to Islam (Ananta et al. 2015). In the study of Putro (2021) on the amalgamation of Confucianism and Buddhism in Indonesia, it became evident that within this evolving landscape, individuals were indisputably impacted by the spiritual aspects of Buddhism and other faiths. This influence led to progressively intricate contemplation and identification regarding their religious beliefs.

Such diverse religious characteristics facilitated the development of a distinctive cultural amalgamation among Chinese Indonesians, blending their Chinese heritage with indigenous Indonesian customs. This blending of cultures was influenced by intermarriage, language adaptation, and engagement in local religious practices. Religious identification played a significant role in this aspect (Ang 2001). Religious identity and overall identity have long been closely intertwined for immigrant populations. While Chinese Indonesians adhere to a variety of religions, including Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, Christianity, and Islam, “the vast majority of Buddhists are indeed of Chinese descent” (Suryadinata 2008). Religion plays a pivotal role in shaping their cultural identity (Chia 2020a), influencing their way of life, values, and social interactions and intertwining with their cultural identity. However, challenges persist despite the positive changes in cultural identity among Chinese Indonesians. Stereotypes, occasional instances of discrimination, and political sensitivities related to their identity can impact their cultural expression and sense of belonging (Sai and Hoon 2013). Furthermore, identity formation is a dynamic process, with intergenerational declines frequently observed (Ma 2022; Shen 2017; Zhang 2020, 2021). Therefore, efforts to uphold and promote Chinese Indonesians’ religious and cultural identity remain of paramount significance.

Development of Indonesian Buddhism and identification with Buddhism among Chinese Indonesians

The content, forms, and degrees of identification with Buddhism are closely entwined with the development of religion. Buddhism was introduced to Indonesia as early as the first century, with Borobudur and Mendut temples on the island of Java being cultural remnants of this era (Acri 2014). In the fourteenth century, Islam, introduced by Muslim traders mainly from South Asia, emerged as the predominant religion along the coasts of Java and Sumatra. By the fifteenth century, Islam had become firmly established in the coastal regions of other islands in the archipelago. In contrast, Buddhism experienced a gradual decline, persisting primarily through covert propagation. However, efforts by European scholars, the Theosophical Society, and local Peranakan Chinese led to a revival of interest in Buddhism during the 19th and 20th centuries. Various Buddhist organizations have emerged, incorporating diverse Buddhist traditions, such as Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna Buddhism, and captured the attention of both indigenous and Chinese communities in Indonesia (Chia 2018). In the mid-twentieth century, Indonesia gained independence, prompting active participation in and the propagation of Buddhism by Indonesians, including Chinese Indonesians. Initiatives such as the Indonesian Buddhist Association (Walubi) and Indonesian Buddhist Youth (Pemuda Buddha Indonesia), as well as movements such as the Indonesian Buddhayana Movement, initiated by the monks Bhikkhu Ashin Jinarakkhita and Bhikkhu Sugandha, played pivotal roles in promoting Buddhism and fostering a sense of identity among young Buddhist followers. The ensuing changes included, for instance, the removal of traditional Chinese cultural rituals from Mahāyāna Buddhism; the introduction of the pursuit of doctrinal scriptures, making Buddhism more “religious”; and the incorporation of the monotheistic concept of “God” into Buddhism (Chia 2018). These efforts also positively impacted the unity of the Chinese Indonesian community and their identification with Buddhism (Chia 2018; Yulianti 2022).

In recent years, the identification of Chinese Indonesians with Buddhism has undergone additional transformation. While Chinese Indonesian Buddhists often align themselves with Mahāyāna Buddhism, the influence of Indonesian history, culture, and global multicultural trends has led to an increasing integration of Buddhism with local culture and other religions. Iconic Buddhist temples such as Borobudur and the construction of new temples underscore Buddhism’s enduring impact on Indonesian culture and architectural heritage, attracting not only Buddhists but also visitors from around the world. In modern society, Indonesian Buddhist groups collaborate more extensively with other religious communities than their predecessors did, engaging in diverse social and cultural activities (Chin and Tanasaldy 2019).

The uniqueness of the identification with Buddhism unfolds across several dimensions, including aspects such as identity, religious practices, symbols, and impressions. The concept of “conversion” emphasizes the membership and identity facets within the faith, as discussed by Jindra (2011) and Suchman (1992). In Indonesia, the Directorate General of Buddhism under the Ministry of Religious Affairs supervises a formal ritual known as Ti-Sarana Gamana, commonly referred to as Visudhi Tisarana, through which individuals embrace Buddhism (Ministry of Religious Affairs of Klungkung Regency 2021). However, an alternative perspective is presented by scholars such as Chau (2006) and Fan and Chen (2014), who characterize the Buddhist approach to faith as “doing religion.” This implies that religious engagement need not strictly involve conversion but can manifest in various enriching forms, aligning with fundamental Buddhist principles such as “impermanence” and “open-mindedness” (McMahan 2008; Setefanus 2019).

A significant discussion on being religiously and culturally Buddhist has elucidated individuals’ attraction to Buddhism as a spiritual journey. Particularly for the youth in modern Indonesia, Buddhism holds a spiritual allure, fosters cultural connections, promotes values and moral conduct, and catalyzes personal growth and spiritual journeys. This perspective aligns with the emerging view that Buddhism can play a role beyond traditional religious frameworks, becoming a dynamic force in individuals’ lives (Chia 2020b).

The modern attractiveness of Buddhism to Indonesian youth is evident in the emergence of new symbols, including Buddhist music, publications, activities, and cultural enterprises that blend traditional recitations with modern adaptations (Li and Wang 2023; Chia 2020b). This synthesis of tradition and modernity effectively captures the hearts of Indonesian youth, solidifying Buddhism as a significant aspect of their lives (Chia 2020b).

Certain facets of Buddhism, such as meditation practices, provide effective techniques for mitigating anxiety in modern society, facilitating the dissemination of Buddhism’s spiritual influence beyond its traditional boundaries (Burton 2010; Wilson 2014; Brooke 2019; Dahanayake 2022). In the era of new global multiculturalism, youth are increasingly pivotal in shaping the future of Buddhist identification, with their diverse experiences contributing to the evolving landscape of Buddhism in Indonesia (Chia 2020b). The fusion of traditional values with modern expressions positions Buddhism as a relevant and adaptive spiritual force, resonating with the evolving needs of Indonesian youth.

Research model

To address the existing gaps in the literature, the researchers employed a comprehensive mixed-methods approach that combined questionnaire surveys and individual interviews. The questionnaire surveys provided a quantitative lens, enabling the researchers to assess prevalence rates and identify potential trends. Simultaneously, individual interviews offered qualitative depth, allowing the study to capture the nuanced experiences, perspectives, and factors influencing the participants’ identification with Buddhism. Through data analysis, the research investigated the overall levels of identification with Buddhism and the dimensional structure, intergenerational change patterns, and influencing factors among Chinese Indonesian youth.

Building upon previous research, the researchers categorized the intricate concept of identification with Buddhism into six discernible dimensions. These dimensions included Buddhist identity, identification with Buddhist symbols, alignment with Buddhist values, recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism. The exploration of Buddhist identity mainly encompassed formal identification and psychological identification. The dimension of identification with Buddhist symbols involved recognizing Buddhist attire, cuisine, and cultural figures. Alignment with Buddhist values focused on the values advocated by Buddhist culture. The recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns included participation in Buddhist religious rituals, lifestyles, and activities. Emotional engagement with Buddhism encompassed attitudes toward Buddhism, such as being willing to actively seek out Buddhist knowledge and practice Buddhist values. Perceptions of Buddhism primarily focused on participants’ overall impressions of Buddhist monastic orders, activities, imagery, and related aspects.

The investigation of intergenerational changes in identification with Buddhism primarily explored the evolving pathways across three generations: grandparents, parents, and youths.

Based on this, the study presents the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The degree of Buddhist identity is positively correlated with the degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 2: The degree of identification with Buddhist symbols is positively correlated with the degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 3: Alignment with Buddhist values is positively correlated with the degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 4: Recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns is positively correlated with the degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 5: The degree of emotional engagement in Buddhism is positively correlated with the degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 6: The level of positive perceptions of Buddhism is positively correlated with the degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 7: The degree of identification with Buddhism among grandparents is positively correlated with youths’ degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 8: The degree of identification with Buddhism among parents is positively correlated with the youths’ degree of identification with Buddhism.

Hypothesis 9: Identification with Buddhism is influenced by individual factors such as parents’ occupation and regional distribution.

The ultimate objective of this study is to formulate an intergenerational model of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation (depicted in Fig. 1). Figure 1 illustrates that identification with Buddhism comprises six dimensions: Buddhist identity, identification with Buddhist symbols, alignment with Buddhist values, recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism. Furthermore, such identification accentuates the impact of generational transitions and individual factors.

Materials and methods

Methods

Questionnaire survey

This study developed the “Questionnaire on Generational Transition of Identification with Buddhism among Young Chinese Indonesians (Preliminary Draft)” based on the “Ethnic Identity Scale” by Phinney and Devich-Navarro (1997), the “Culture Identity Questionnaire for Hani Ethnic Minority Adolescents” compiled by Hu et al. (2010), the religion scale created by Abu-Rayya et al. (2009) and the Religious Identity Scale developed by Case and Chavez (2017).

The questionnaire consisted of three sections: demographic information, items rated with a five-point Likert scale, and open-ended questions. The demographic information section included the respondents’ place of residence, age, religion, generational status, education level, family education level, parents’ occupations, and related factors. The five-point Likert scale items were formulated to evaluate the identification with Buddhism among young Chinese Indonesians across the six dimensions (refer to Table 1). Open-ended questions supplemented the Likert scale items, allowing respondents to provide additional information. For instance, following the statement “I often celebrate Buddhist holidays with my parents”, participants were asked to list which holidays they frequently celebrate.

After an evaluation by three experts, the preliminary draft of the questionnaire was administered to ten young Chinese Indonesians for pilot testing. Following the pilot test, revisions were made to the questionnaire by the research team. This included the addition of items and the deletion or modification of items that contained unclear semantics or lacked precise translation. These refinements culminated in the final version of the questionnaire.

Individual interviews

When administering the survey questionnaire, the researchers simultaneously inquired whether respondents were willing to participate in interviews and provide their contact information. Among those who agreed, the researchers selected respondents whose survey questionnaire answers displayed representative scoring patterns. Subsequently, interviews were conducted that focused on the aspects of interest, primarily discussing the state of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation and their family members and friends. These interviews aimed to explore the dimensions and influencing factors related to identification with Buddhism and its generational transitions. The individual interviews in this study were conducted using a semistructured, question-and-answer format, and all interviews took place online. Before the interviews, the research team provided participants with an interview outline to give them an overall understanding of the topics to be discussed. During the interviews, participants provided their consent for the recording of the dialog and interview materials by the author.

The interview outline is presented in Table 2.

Participants

Between 2022 and 2023, survey forms were distributed in 33 provinces of Indonesia, including national private schools, trilingual schools, tutoring centers, international schools, and universities. The survey participants consisted of primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-level students. This survey was part of the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Heritage Research Project, which encompassed various aspects, including language heritage, identity, and religious affiliation. Over 3000 questionnaires were collected for the entire project. Some questionnaires were completed by students in school, while others were distributed by teachers for students to complete at home and were later collected.

Regarding the religious affiliation questionnaire used in this paper, a total of 330 valid responses were collected. Respondents who lacked interest or understanding of Buddhism had the option to abstain from responding to this questionnaire. Responses consisting solely of personal information without answers to subsequent questions were deemed invalid. Among the respondents, the average age was 15 years, and 97.87% were younger than 30. Moreover, 96.06% of the participants were descendants of third, fourth, fifth, or later generations of Chinese immigrants. A total of 10 respondents participated in individual interviews regarding religious matters after completing the survey questionnaire. The survey sample was wide-ranging and representative, making it suitable for further analysis and research. The demographic distribution of the surveyed participants is presented in Table 3.

Results

The collected survey data underwent statistical analysis using SPSS 26, and a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis was conducted using SPSSAU. The overall reliability coefficient (Cronbach’s alpha) of the questionnaire was calculated to be 0.979. The absolute values of the standardized factor loadings (std. estimate) for all items exceeded 0.6 (specific data omitted), with p values below 0.05, indicating the high reliability and validity of the data. The questionnaire demonstrated good internal consistency and validity, rendering it suitable for further analysis. The questionnaire comprised an internal structure scale for identification with Buddhism and a generational transition scale for identification with Buddhism. The identification with Buddhism structural scale encompassed six dimensions, while the generational transition scale comprised three dimensions. CFA was employed to assess these scales. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for all nine dimensions exceeded 0.5, and the composite reliability (CR) values exceeded 0.7, signifying a high level of convergent validity for all scale dimensions. Refer to Table 4 for details.

In conclusion, both the identification with Buddhism structural scale and the generational transition scale within the questionnaire exhibited sound measurement properties, rendering them suitable for further analysis.

Dimensions of identification with Buddhism and the fundamental characteristics of each dimension

Descriptive data analysis reveals that the average scores for the six constituent dimensions of identification with Buddhism (Buddhist identity, identification with Buddhist symbols, alignment with Buddhist values, recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism) all exceed 3 points among the respondents. This indicates a prevailingly positive orientation toward Buddhism among this demographic.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, among the respondents, the mean scores for alignment with Buddhist values and recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns are 4.499 and 4.292, respectively, significantly surpassing the scores for other dimensions. Buddhist identity, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism demonstrate comparable levels of identification. Conversely, the dimension of identification with Buddhist symbols shows the lowest level of engagement (SD = 1.269), implying noteworthy variability among participants within this specific dimension.

In terms of Buddhist identity, within today’s young Chinese Indonesian generation, only 4% firmly identified as devout Buddhists in response to the question “Do you consider yourself a devout Buddhist?” Meanwhile, 48.79% of respondents opted for the response “I suppose so.” A mere 8.48% selected “No.” Cross-analysis results indicate that among respondents who identified as “Christian,” “Catholic,” or “Muslim” in their personal information, a notable percentage also expressed interest in Buddhism. This suggests that despite Islam being the predominant religion in Indonesia, over half of the respondents maintain some level of natural affinity toward and a sense of belonging with Buddhism.

When questioned about their openness to “dating someone of another faith,” 89.4% of the respondents indicated that they would be willing to date individuals from Buddhist, Muslim, or Christian backgrounds. This stands in stark contrast to a study by Wang (2006), where only 9% of Indonesian respondents approved of cross-religious marriages based on love. In the interviews, participants also acknowledged that marriage is a more complex matter. However, they noted that if they were to meet someone they liked from a different religion, they could start dating first and discuss the matter later. One possible explanation for this shift could be attributed to evolving cultural norms and increased exposure to diverse perspectives, driven by globalization and the interconnectedness of today’s world. The young generation today appears to embrace a more inclusive and open-minded approach to relationships, valuing personal connections over rigid religious boundaries.

Regarding alignment with Buddhist values, among values such as “compassion,” “generosity,” “nonkilling,” and “mindfulness,” the highest endorsed value among respondents is “karma.” During interviews, participants noted that “karma” resonates more distinctly with Buddhism and positively influences engaging in virtuous conduct.

Concerning the recognition of Buddhist behaviors, the cultural practice of “celebrating Buddhist festivals with family” emerges as the two most prominent cultural elements of Buddhist identity among today’s young Chinese Indonesian generation. The majority of respondents continue to celebrate traditional Buddhist festivals such as Vesak Ashoka’s birthday and Ullambana with their families. One interviewee mentioned that “the most memorable moments are during the New Year and Vesak when we go to Vihara Dharma Bhakti with our family to light incense and offer prayers.” This underscores the enduring significance of celebrating Buddhist festivals with family in shaping the religious identity of Chinese Indonesian youths.

Concerning identification with Buddhist symbols, the young Chinese Indonesian generation today demonstrates a lower level of alignment and substantial diversity in recognition than their forebearers did. The results of the t test indicate that compared to the affinity with traditional Buddhist symbols, such as temple architecture and Buddhist history, there is a significantly higher affinity with modern Buddhist symbols, including celebrity monks, Buddhist characters in TV dramas, and innovative Buddhist products. The level of identification with traditional Buddhist symbols is 3.33 ± 1.33, whereas the level of identification with modern Buddhist symbols reaches 3.7 ± 1.34. The associated significance value (p) is 0.001, suggesting a significant difference in the levels of identification with these two categories. For this generation, Borobudur serves as a tourist attraction with characters and stories that warrant exploration, although not always invoking a sense of sacred veneration. Nonetheless, distinguishing among Taoism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and similar traditions remains challenging for the majority of youths. Some respondents even consider “Guangong” as one of the idols in Buddhism. Of course, this is related to the amalgamation of Indonesia’s local Buddhist culture. In Jakarta’s Chinatown at the Vihara Dharma Bhakti, the idols of Buddha and Guanyin are enshrined like other deities commonly revered by the Chinese community, such as Mazu, Caishen, and Tudi. Furthermore, there are even distinctive local deities, such as Guangze Zunwang, Qingshui Zushi, and Huize Zunwang.

Regarding emotional engagement with Buddhism, despite familiarity with renowned Buddhist figures and narratives such as Adi Buddha, Siddhartha Gautama, Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, and “Journey to the West,” modern Buddhist personalities (e.g., Bhante Atthadhiro in Indonesia, Master Hsing Yun in Taiwan) attract a more dedicated following. One respondent even emphasized that encountering notable Buddhist figures serves as her primary motivation for studying Dharma. This also enhances her interest in and attraction to Buddhism.

For perceptions of Buddhism, the average scores among all respondents reached 3.541, indicating an overall favorable perspective on Buddhism. During the interviews, over two-thirds of today’s young Chinese Indonesian generation expressed their affinity for actively participating in sutras and sermons through new media platforms such as the group account “Indonesian Buddhist Community” and the personal account “Berhati” on YouTube, among others. They exhibited an interest in modern Buddhist stories and philosophical viewpoints related to daily Buddhist life. The interviews also revealed that elegantly written books and modern philosophical narratives play a pivotal role in sparking their interest in popular Buddhist works such as “What Does the Diamond Sutra Say?” and “Life and Society.”

Overall level of identification with Buddhism and demographic distribution of each dimension

The results of the analysis of variance indicate that age, education level, and parental occupation are significantly correlated with the extent of identification with Buddhism. For detailed information, please refer to Table 5.

As illustrated in Table 5, disparities in identification with Buddhism emerge across groups within the young generation of Chinese Indonesians:

-

(1)

Respondents’ education level and parental occupation substantially impact the overall level of identification with Buddhism and its dimensional composition.

The data show that there is a noticeable upward trend in identification with Buddhism among young Chinese Indonesians as their level of education increases. In terms of identification with Buddhism, there is an overall increase of 6.99% from primary school graduates to master’s degree graduates. Young individuals whose parents are entrepreneurs and businesspeople exhibit the highest levels of identification with Buddhism, followed by laborers and farmers. In contrast, young individuals whose parents are civil servants or company employees show lower levels of identification with Buddhism. Among various groups, the dimension with the highest level of identification remains Buddhist values. However, there are distinctions in terms of explicit behavioral identification. Young individuals whose parents are company employees or laborers/farmers tend to show higher levels of behavioral identification with Buddhism than those whose parents are entrepreneurs, businesspeople, or civil servants. Moreover, young individuals with parents in business and civil service show greater interest in Buddhist symbols. For additional insights, please refer to Fig. 3.

-

(2)

Differences in identity levels exist across age groups of respondents.

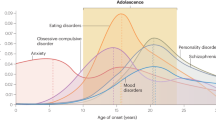

For this study, respondents were divided into five age groups: 6–12 years old, 13–19 years old, 20–30 years old, 31–40 years old, and above 40 years old. The survey results indicate that the 20–30 age group exhibits the highest level of identification with Buddhism, while the 13–19 age group displays the lowest. In children aged 6–12, there is a stronger identification with Buddhism than among the next-oldest group, with an average score of 4.034. However, during the adolescent phase (13–19 years), this level declines to an average score of 3.79. Intriguingly, among young adults aged 20–30, there is a notable increase in identification with Buddhism (average score rising to 4.166), followed by a slight decline after the age of 30 (average score decreasing to 3.877).

-

(3)

Regional distribution of Buddhist identification levels

The study participants were categorized into four groups based on geographical region: Sumatra Island (encompassing provinces such as North Sumatra Province, West Sumatra Province, and South Sumatra Province), the Java region (encompassing provinces such as West Java Province, Central Java Province, Yogyakarta Province, and East Java Province), the Jakarta region (including Jakarta Capital Special Region and Banten Province), and other archipelagos (including provinces such as Riau Islands Province, West Kalimantan Province, and South Sulawesi Province). Noticeable variations in identification levels were observed. The lowest levels were found in the Java region, while the highest levels were observed in the other archipelagos. Significant distribution disparities were also identified for emotional engagement with Buddhism, recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, identification with Buddhist symbols, and Buddhist identity (refer to Table 6).

Generational evolution and dimensional aspects of identification with Buddhism

The research outcomes show that the average scores for generational identification with Buddhism are 3.95 for grandparents, 3.87 for parents, and 3.76 for youths within the current Chinese Indonesian population. The analysis of variance results illustrate noteworthy distribution discrepancies among the generations, yielding a p value of 0.018, which falls below the significance threshold of 0.05. This suggests that while the young Chinese Indonesian generation currently maintains a certain level of affinity toward the religious beliefs held by their grandparents and parents, their adherence to these beliefs is weaker than that of their grandparents. Moreover, supplementary data analysis in this study reveals varying rates of generational decline across distinct dimensions. Detailed insights can be found in Fig. 4.

As illustrated in Fig. 4, dimensions such as emotional engagement and recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns exhibit relatively modest decline rates, amounting to 3.01% and 3.06%, respectively. However, the dimension of identification with Buddhist symbols displays a higher rate of decline at 7.88%. The average score for the dimension of alignment with Buddhist values among the young Chinese Indonesian generation still exceeds 4 points, a decline of 5.11% from their grandparents.

Generational transition model of identification with Buddhism among the today’s young Chinese Indonesian generation

To examine the influence of generational decline on the overall magnitude and dimensions of identification with Buddhism within the young Chinese Indonesian generation, the researchers constructed a structural model of identification with Buddhism encompassing six dimensions: Buddhist identity, identification with Buddhist symbols, alignment with Buddhist values, recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism. The concept of generational decline was segmented into two facets: decline between parents and children and decline between grandparents and parents. This facilitated the establishment of a generational decline model for identification with Buddhism within a familial context. Subsequently, these models were harmonized, and structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed to formulate the generational evolution model of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation. The parameters of the model are outlined in Table 7.

As shown in Table 7, most indicators meet the requirements for a good fit between the model and the scale, implying the model’s validity. The modeling results of the generational evolution model of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation are illustrated in Fig. 5.

This image displays the results of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) analysis, showing the factors influencing identification with Buddhism. The left side of the image represents intergenerational factors affecting identification with Buddhism, while the right side represents the dimensions influencing identification with Buddhism.

As depicted in Fig. 5:

-

(1)

Buddhist value alignment and perceptions of Buddhism significantly counteract the generational decline in identification with Buddhism. An increase of 1 point in Buddhist value alignment offsets generational decline by 1.392 points, while a 1-point increase in perceptions of Buddhism offsets generational decline by 0.619 points.

Previous statistical results have already demonstrated that Buddhist value alignment constitutes a pivotal aspect of the generational transmission of identification with Buddhism within the young Chinese Indonesian generation. This underscores the particular significance of passing down Buddhist values for the continuity of identification with Buddhism. Enhanced perceptions of Buddhism also contribute significantly to elevating levels of identification with Buddhism. The model reveals that the concepts of “karma” and “impermanence” make the most substantial contributions to the inheritance of Buddhist values. Statements such as “I believe the Buddha blesses everyone” and “I believe the Buddha guides everyone toward goodness” are significantly correlated with the overall level of identification with Buddhism, with correlation coefficients of 0.865 and 0.793, respectively.

-

(2)

Identification with Buddhism by grandparents and parents significantly and positively influences identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation. With every 1-point decrease in generational decline, the overall level of identification with Buddhism increases by 0.351 points. The decline between generations of parents and children has a greater impact on the overall decline level: each 1-point decrease in the decline between parents and children corresponds to a 1-point decrease in generational decline. This highlights the crucial role of the family in the transmission of identification with Buddhism, particularly within close-knit families, as the most vital environment for cultivating identification with Buddhism.

Discussion

Identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation exhibits greater diversity, inclusiveness, and contemporaneity than among previous generations

The data analysis results demonstrate that under the influence of government policies promoting multicultural development and the global trend of multiculturalism, there has been a significant increase in interreligious interaction and fusion. Among the young Chinese Indonesian generation, diverse and modern perspectives on the Buddhist faith and its practices are evident.

First, the boundaries among religious identity, religious symbols, and religious values have been blurred. During interviews, respondents expressed that regardless of their religious affiliation, they find no issue with reading Buddhist books, seeking blessings from temple monks, or obtaining blessed items. Items integrating Buddhist symbols are also popular on online shopping platforms. Some creative products even combine elements from multiple religious denominations. For example, a pendant with the Six-Syllable Mantra combines symbols from the Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions. Television characters and stories that capture young audiences’ interest often carry hybrid elements. For instance, their favorite characters might possess angelic wings and wear Buddhist prayer beads. Elements from the popular culture figure “Hanoman” also embody traits of both the Buddhist character “Sun Wukong” and the indigenous Indonesian figure “Hanoman.” Many young Chinese Indonesians also perceive “Sun Wukong” as a symbol and idol. In terms of religious practices, utilizing modern media is also a prevailing trend. For the young Chinese Indonesian generation, seeking blessings for secular reasons, such as academic progress and wealth, remains a significant Buddhist practice, but the procedural aspects are often unfamiliar. On video-sharing websites, there are dozens of videos related to “Tutorial Sembahyang Keberuntungan” (Blessing Tutorial), with the most popular video garnering over 200,000 views. Adapted Buddhist rock music is also well received. As of the publication date, the song “Buddha Loves Me” has accumulated over 120,000 views on YouTube.

Indonesian Buddhist culture is characterized by distinct hybrid features influenced by historical and modern factors. For instance, during the assimilation policy period, Confucian, Taoist, and Buddhist idols were often worshiped together, bringing spiritual comfort and support to the youth during their childhood and adolescence. Additionally, important Buddhist figures and events in Indonesian history, such as Ashin Jinarakkhita’s Buddhayāna movement, which promoted nonsectarian doctrines and practices in alignment with the national discourse of “Unity in Diversity,” have fostered cultural fusion both within and outside Buddhism. This has led to a more open attitude among young Chinese Indonesians, with their identification with Buddhism in terms of history, culture, tradition, and lifestyle being constructed within their diverse living environment. The dissemination of diverse and hybrid Buddhist symbols helps achieve balance and diversification in the development of Buddhism alongside other religions.

Significant distribution disparities in identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation

The research data illustrate the presence of group disparities in identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation. Regarding age distribution, the current cohort of young adults (20–30 years old) was born and raised during a period of relaxed restrictions, witnessing the revival and prosperity of the Chinese Indonesian community. Relatively lenient policies and active communication within the Chinese Indonesian community significantly contribute to their higher level of identification with Buddhism than that among preceding and succeeding generations. Given Indonesia’s policy development toward the Chinese Indonesian community since the end of the New Order era in 1998, cultural practices related to Chinese heritage, Chinese language education, and Chinese Indonesian community organizations have experienced revitalization. Many activities organized by Chinese Indonesian community groups are themed around Buddhist gatherings and festivals. This has not only elevated the cultural propagation level among Chinese Indonesians but has also further strengthened their sense of identity as Buddhist believers. From a geographical perspective, there are notable differences in identification levels across various regions. In particular, the higher levels observed in the other archipelago and the comparatively lower levels on Java Island can be ascribed to a convergence of historical, cultural, and religious factors. The prevalence and historical presence of distinct religions across various regions can also impact these identification levels. For instance, the regions in the other archipelagos might have historically engaged in a broader spectrum of cultural exchanges, potentially including interactions with Buddhist influences. This may have fostered a greater degree of familiarity and acceptance toward identification with Buddhism among the population. The diverse cultural characteristics of the Jakarta region also make the area more accommodating of the presence and development of identification with Buddhism. In contrast, Java Island has experienced more dominant Islamic and Javanese cultural influences, which may contribute to the observed lower levels of identification with Buddhism. This is a delicate and multifaceted issue, and further research regarding this issue can be done to elucidate the geographical distribution and development of religious beliefs in Indonesia.

From an individual standpoint, there are notable differences in identification with Buddhism among distinct groups such as entrepreneurs, businesspeople, and low-income workers. During interviews, respondents highlighted that higher identification with Buddhism is observed at the “extremes” of this spectrum. Entrepreneurs and businesspeople perceive their career achievements as blessings from the divine due to the higher risks and rewards associated with their professions. On the other hand, the children of civil servants and corporate employees express dissatisfaction on this point, stating, “Being identified as Buddhists hasn’t brought any evident advantages to us (and our parents). However, whenever there’s a scandal or negative news related to Buddhism, our classmates always enjoy discussing it with us.” This creates an awkward situation, naturally diminishing their level of identification. Conversely, the children of laborers and farmers aspire to involve their children in various religious activities, as they experience warmth and practical convenience from fellow believers within the religious community. Simultaneously, they perceive their capabilities as limited and seek blessings from the “bodhisattvas” to bring hope to their future development. These practical factors influence their level of identification with Buddhism to a certain extent.

The continuity of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation still centers on families, sprouting the new hope amid decline

Previous research has indicated that as Indonesian citizens, Chinese Indonesians inevitably establish increasing connections with other ethnicities and religions (Lin 1992). This may lead to cognitive dissonance between their family history, culture, traditions, and way of life, potentially resulting in detachment from their ethnic sentiments and culture (Shen 2017). However, the data from this study suggest that despite a waning in the level of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation, their means of practice and approach to Buddhist identification have become more diverse, contemporary, and pragmatic.

Growing up in the local cultural context of Indonesia, the young generation of Chinese Indonesians are proficient in the Indonesian language, willing to intermarry with other Indonesian groups, and identify more or less with the cultural aspects of Buddhism. However, the local culture has become part of their daily lives and identity, while their understanding of Buddhism often remains confined to certain symbols and slogans within family gatherings and the Chinese community. Compared to their grandparents, their closeness to typical and traditional Buddhist symbols and ritualistic practices such as statues, ordination, fasting, and chanting has diminished. However, this does not mean that they entirely reject Buddhist values. They still broadly identify with values such as karma and reverence for the Buddha. Their pursuit of religious practices and beliefs has also become more pragmatic. One respondent mentioned, “I can’t even differentiate between Buddhist saints and Taoist saints. But, before looking for a job or taking exams, I pray to bodhisattvas with my friends.”

The findings also reveal that Buddhist values and religious impressions can significantly counteract the generational decline in identification with Buddhism. Participants noted that the young Chinese Indonesian generation widely considers doing good deeds to be a significant marker of success, and the virtue of “willingness to give” remains an admired trait. Understanding Buddhist doctrines has also become a way for Indonesian youth to find spiritual partners, life partners, and even professional partners.

Furthermore, identification with Buddhism among grandparents and parents has a significant and positive impact, with Buddhist behavioral patterns and emotional engagement still originating and being maintained within close-knit families. It is evident that engaging in cultural activities within families and upholding the Buddhist values that foster family bonds can effectively sustain identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation. For example, Chinese Indonesian community organizations and religious groups can actively organize various cultural activities, such as meditations, blessings, and even Buddhist music concerts, in religious places that young people frequently visit, such as Vihara Dharma Bhakti, Vihara Avalokitesvara, and Vihara Maitreya. These activities should be organized around the family unit to enhance family cohesion while maintaining the current level of diversity in cultural heritage.

Development of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation in the context of global multiculturalism

Multiculturalism and cultural hybridization stand as prevalent trends in the modern world. Within a global framework, the evolution of Buddhism appears to necessitate a balance between preserving its inherent attributes and embracing diversity (Sen 2018; Tan 2022). Buddhist doctrines emphasize the pursuit of spiritual tranquility, offering an inclusive and adaptive possibility for individuals experiencing spiritual anxiety and restlessness under the pressures of globalized materialism (Wilson 2014; Dahanayake 2022). In the construction of the landscape of identification with Buddhism, the selection of values and cultural elements can extend to a broad range of modern cultural components. Attending to aspects linked with indigenous culture beyond the confines of traditional values and cultural content within identification with Buddhism can enable the incorporation of modern values and symbols into the global corpus of shared culture. As a result, this can lead to crafting a more extensive and modern array of collective cultural elements. This approach is also instrumental in constructing a shared memory among today’s Indonesian youths of various ethnicities and faiths, thereby establishing a robust cultural foundation for future amicable exchanges.

In the context of cultivating future Buddhist adherents, the conceptual framework and modes of practice should resonate as closely as possible with the lives of youth. Introducing technology and creative arts into religious practices is essential to arouse the interest of young individuals and generate pathways that transcend race, religion, and culture, enabling them to explore Buddhist philosophies they might not otherwise encounter. Through mediums such as creative arts, contemporary music, and other platforms, integrating traditional elements of Indonesian culture into Buddhist works empowers young individuals to forge connections with their roots and spirituality. This allows them to convey values such as compassion, mindfulness, and social responsibility. Through such avenues, individuals can be encouraged to cultivate positive traits and moral behavior aligned with Buddhist principles.

Symbols and slogans of this nature should be prominently featured in cultural events, festivals, and gatherings, creating opportunities for meaningful interaction among youths in a spiritual context. Creative products, among other mediums, can serve as bridges and gifts, facilitating communication between youths and their families. This can not only mitigate the perplexities arising from intergenerational decline in Buddhist identification but also provide a sense of belonging and self-empowerment within faith communities and families. Sharing these symbols and music with peers adhering to different religious beliefs promotes interfaith dialog and comprehension. The universal messages of compassion and inner peace inherent in these expressions form the bedrock of dialog. Adapting traditional and modern, diversified Buddhist symbols, behaviors, and values to the local context will enrich and advance pluralism as a facet of Buddhism.

Conclusion

Based on the results presented in this study, identification with Buddhism can be divided into the following six dimensions: Buddhist identity, identification with Buddhist symbols, alignment with Buddhist values, recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism. All six dimensions show a significant positive correlation with identification with Buddhism. The analysis results from this study also reveal that today’s young Chinese Indonesian generation exhibits higher levels of alignment with Buddhist values and recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns, demonstrating greater diversity and inclusivity than among previous generations. In terms of identification with Buddhist symbols, the young Chinese Indonesian generation exhibits distinct modern features.

This cohort displays varied attitudes toward identification with Buddhism. Their highest level of identification with Buddhism is observed when they connect their personal experiences with Buddhist values and spirituality. The levels of alignment with Buddhist values and recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns notably surpass other dimensions. Values such as “karma” and cultural behaviors such as “celebrating Buddhist festivals” stand as the two highest cultural elements of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation.

Buddhist identity, emotional engagement with Buddhism, and perceptions of Buddhism present lower levels of identification. While a minor portion of Chinese Indonesian youths identify as devout Buddhists, a substantially larger portion express familiarity, affinity, and interest in Buddhist culture and spirituality. They hold more open attitudes toward adherents of other religions.

The dimension of identification with Buddhist symbols presents the lowest level, with considerable disparities among respondents. Identification with Buddhist symbols among the young Chinese Indonesian generation is mixed extensively with local and other religious cultures. A growing number of Chinese Indonesian youths tend to appreciate modern Buddhist symbols such as monks, Buddhist narratives, and lucky Buddhist memorabilia.

Regarding the internal distribution within this group, age, educational attainment, geographical location, and parental occupations are significantly correlated with the level of identification with Buddhism. Chinese Indonesians between the ages of 20 and 30 manifest the highest levels of identification with Buddhism. Regarding individual factors, the children of entrepreneurs and businesspeople exhibit the highest identification levels, followed by those of laborers and farmers. Conversely, the children of civil servants and corporate employees demonstrate the lowest levels of Buddhist identification. The Java region and other archipelago regions show the lowest and highest levels, respectively.

From a generational perspective, identification with Buddhism among grandparents, parents, and children demonstrates an overall declining trend, with varying rates of decline across dimensions. Emotional engagement and recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns dimensions exhibit relatively weaker declines, whereas the recognition of Buddhist behavioral patterns is experiencing a higher decline rate. Despite the weakening of identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation, alignment with Buddhist values and perceptions of Buddhism significantly offsets the generational decline in identification with Buddhism. The identification with Buddhism among grandparents and parents can also notably and positively influence the young Chinese Indonesian generation’s identification with Buddhism. The preservation of family heritage plays a substantial and constructive role in maintaining the level of identification with Buddhism.

Perpetuating identification with Buddhism can commence by broadening the scope of diverse Buddhist symbols, strengthening the bonds of familial transmission, and promoting value dissemination within diverse families. This approach enhances generational transmission efficiency while pursuing harmonious family development. Additionally, it assists the young Chinese Indonesian generation in cultivating future-oriented, distinctive multiculturalism, facilitating the shared development of individuals, communities, and the global landscape.

Research limitations and future directions

The survey sample in this study is limited to Chinese Indonesian individuals who have opted for Chinese language courses in universities and secondary schools in Indonesia and who identify as having Chinese heritage. Consequently, the sample may not be representative of the entire population. It is possible that the sample does not include individuals who, despite lacking an interest in learning Chinese, exhibit an interest in Buddhism. Likewise, the sample may exclude those who have taken Chinese language courses but hold different views on Buddhism or lack interest in religion. By employing a cross-sectional design, this study captured data at a specific point in time. The questionnaire survey involved passive data acquisition and is thus unable to help establish causal relationships or track changes in identification with Buddhism over time or across regions. The predictive implications of the findings also do not encompass broader aspects such as domestic and international policy trends and global economic and cultural developments, which historically bear strong relevance to the development of religious identities.

In the future, a longitudinal approach can be pursued to comprehensively understand how identification with Buddhism evolves over time and across generations. Furthermore, future studies may cover a broader geographical scope and apply comparative analysis across diverse cultural and religious contexts, facilitating the identification of commonalities and disparities in intergenerational religious identity transmission. Exploring the dynamics of interactions among religions and their impact on cultural diversity and how these dynamics influence identification with Buddhism among the young Chinese Indonesian generation will offer deeper insights into the interplay between traditional Buddhist values and modern influences in shaping the religious identity of the demographic. Future studies should also address the effects of globalization, migration, and cross-cultural interactions on the religious identity and practices of today’s young Chinese Indonesian generation. Given Indonesia’s diverse religious landscape, examining the interactions between Buddhism and other religions can unveil the intricate religious panorama and developmental trajectories within the region.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its Supplementary Information files.

References

Abu-Rayya HM, Abu-Rayya MH, Khalil M (2009) The multi-religion identity measure: a new scale for use with diverse religions. J Muslim Ment Health 4(2):124–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564900903245683

Acri A (2014) Birds, bards, buffoons and Brahmans: (Re-)tracing the Indic roots of some ancient and modern performing characters from Java and Bali. Archipel 100(88):13–70

Ang I (2001) On not speaking Chinese: living between Asia and the West. Routledge, London, UK, p 24–25. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203996492

Ananta A, Arifin EN, Hasbullah MS, Handayani NB, Pramono, A (2015) Demography of Indonesia’s ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore, p 253–281

Burton D (2010) A Buddhist perspective. In: The Oxford handbook of religious diversity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, p 321–326

Brazier R (2006) In Indonesia, the Chinese go to church. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/27/opinion/in-indonesia-the-chinese-go-to-church.html

Brooke S (2019) The promise of the universal: non-Buddhists’ accounts of their Vipassanā meditation retreat experiences. Religion 49(4):636–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2019.1584130

Case SS, Chavez E (2017) Measuring religious identity: developing a scale of religious identity salience. International Association of Management, Spirituality and Religion, USA, p 25–27

Chau AY (2006) Miraculous response: doing popular religion in contemporary China. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Chia JMT (2018) Neither Mahāyāna nor Theravāda: Ashin Jinarakkhita and the Indonesian Buddhayāna Movement. Hist Relig 58(1):24–63

Chia JMT (2020a) Monks in motion: Buddhism and modernity across the South China Sea. Oxford University Press, New York

Chia JMT (2020b) Singing to Buddha: the case of a Buddhist Rock Band in contemporary Indonesia. Archipel 100:175–197

Chin J, Tanasaldy T (2019) The ethnic Chinese in Indonesia and Malaysia: the challenge of political Islam. Asian Surv 59(6):959–977

Dahanayake N (2022) Spirituality and suffering. World Futures 78(5):311–338

Fan L, Chen N (2014) “Conversion” and the resurgence of Indigenous religion in China. In: Rambo L, Farhadian C (eds) The Oxford handbook of religious conversion. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, p 556–577

Hoon CY (2006) Assimilation, multiculturalism, hybridity: the dilemmas of the ethnic Chinese in post-Suharto Indonesia. Asian Ethn 7(2):149–166

Hu FW, Zhang Z, Li LJ (2010) Hanizu qingshaonian xuesheng wenhua rentong de lilun goujian ji wenjuan chubu bianzhi [Theoretical construction and preliminary questionnaire development on cultural identity of Hani ethnic minority adolescent students]. Honghexueyuan xuebao [J Honghe Univ] 8(03):12–17 and 47. (In Chinese)

Jindra IW (2011) How religious content matters in conversion narratives to various religious groups. Sociol Relig 72(3):275–302

Li F, Wang Q (2023) Constancy and changes in the distribution of religious groups in contemporary China: centering on religion as a whole, Buddhism, protestantism and folk religion. Religions 14(3):323

Lin QY (1992) Lun wenhua rentong yu huaren shehui [The demonstration of cultural identity in the Chinese society]. Huaqiao Huaren lishi yanjiu [J Overseas Chin Hist Stud] 01:11–19. (In Chinese)

Ma F (2022) Yinni Huaren de wenhua rentong yu bentu rongru—jiyu Huawen wenxue shijiao [The cultural identity and local integration of Chinese Indonesians: from the perspective of Chinese literature]. Huaqiaodaxue Xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) [J Huaqiao Univ (Philos Soc Sci)] 4:46–52. https://doi.org/10.16061/j.cnki.cn46-1076/c.2022.04.007. (In Chinese)

Ministry of Religious Affairs of Klungkung Regency [Kementerian Agama Kabupaten Klungkung] (2021) The organization of Buddhists participates in the Ti-Sarana Gamana Ceremony (Visudhi Tisarana Upasaka/i) for the Sudharma Family [Penyelenggara Buddha Hadir Dalam Upacara Pengukuhan Tisaranagamana (visudhi tisarana upasaka/i) Kepada Keluarga Bpk. Sudharma]. https://bali.kemenag.go.id/klungkung/berita/23653/penyelenggara-buddha-hadir-dalam-upacara-pengukuhan-tisaranagamana-visudhi-tisarana-upasakai-kepada-keluarga-bpk-sudharma (In Indonesian)

McMahan DL (2008) The making of Buddhist modernism. Oxford University Press,2008). Oxford, UK, p 4

Phinney JS, Devich-Navarro M (1997) Variations in bicultural identification among African American and Mexican American adolescents. J Res Adolesc 7(1):3–32

Putro MZAE (2021) Confucian’s revival and a newly established Confucian institution in Purwokerto. Analisa J Soc Sci Relig 6(01):63–78. https://doi.org/10.18784/analisa.v6i01.1244

Sai SM, Hoon CY (2013) Chinese Indonesians reassessed: a critical review. In: Sai SM, Hoon CY (eds) Chinese Indonesians reassessed: history, religion and belonging. Routledge, London and New York, p 1–26

Saragih DB (2019) Religions in Indonesia: a historical sketch. In: Hood RW, Contractor SC (eds) Research in the Social Scientific Study of Religion, vol 30, Brill, Leiden, the Netherlands, p 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004416987_005

Sen T (2018) Introduction: networks and identities in the Buddhist world. In: Heirman A, Meinert C, Anderl C (eds) Buddhist encounters and identities across East Asia. Brill, Leiden, p 1–18

Shen L (2017) Yinni Huaren jiating zongjiao xinyang xianzhuang fenxi—jiyu dui Yajiada 500 yu ming huayi qingshaonian de diaocha [Analysis of the religious beliefs in Indonesian Chinese families—based on a survey of over 500 Chinese Indonesian youth in Jakarta]. Huaqiaodaxue Xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) [J Huaqiao Univ (Philos Soc Sci)] 5:99–106. https://doi.org/10.16067/j.cnki.35-1049/c.2017.05.010. (In Chinese)

Suchman MC (1992) Analyzing the determinants of everyday conversion. Sociol Anal 53:S15–S33

Setefanus S (2011) Negotiating the cultural and the religious: the recasting of the Chinese Indonesian Buddhist. https://biblioasia.nlb.gov.sg/vol-7/issue-3/oct-dec-2011/chinese-indonesian-buddhist-cultural-religious/

Setefanus S (2019) Various petals of the lotus: the identities of the Chinese Buddhists in Indonesia. Arch Orient 87:333–383. https://aror.orient.cas.cz/index.php/ArOr/article/view/40

Suryadinata L (2008) Ethnic Chinese in contemporary Indonesia. ISEAS Publications, Singapore, p 48–72; 97–116;124

Tan LO (2022) Conceptualizing Buddhisization: Malaysian Chinese Buddhists in contemporary Malaysia. Religions 13(2):102

Wang AP (2006) Yinni huayi qingshaonian de shenfen rentong yu guojia rentong—Huaqiaodaxue Huawen xueyuan (Jimei) Yinni huayi xuesheng de diaocha yanjiu [Identification and national identity of the teenagers of Chinese descendant in Indonesia]. Wuhandaxue Xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) [Wuhan Univ J (Philos Soc Sci)] 2:282–288. (In Chinese)

Wilson J (2014) Mindful America: meditation and the mutual transformation of Buddhism and American culture. Oxford University Press, USA, p 1–6

Yulianti Y (2022) The birth of Buddhist organizations in modern Indonesia, 1900–1959. Religions 13(3):217

Zhang JY (2021) Dongnanya Huaren wenhua rentong de neihan he texing [Connotation and characteristics of cultural identity of Chinese in Southeast Asia]. Huaqiaodaxue Xuebao (Zhexue shehui kexue ban) [J Huaqiao Univ (Philos Soc Sci)] 3:15–24 and 80. https://doi.org/10.16067/j.cnki.35-1049/c.2021.03.002. (In Chinese)

Zhang XQ (2020) Yindunixiya Bangjiadao Huaren Wenhua Rentong de Lishi yu Xianzhuang tanxi [Historical and current analysis of identification with Buddhism among Indonesian Chinese in Bangka Island, Indonesia]. Shijie Minzu [J World Peoples Stud] 2:109–116. (In Chinese)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China under Grant 21BYY170 and Humanities and Social Science Fund of Ministry of Education of China under Grant 23YJCZH246.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JX: conceptualization, data collection, methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. SM: methodology, writing—review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The questionnaire and methodology employed in this study received approval from the Academic Ethics Committee of Fujian Normal University, with the approval number FNU202201068.

Informed consent

Participation in the study was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from the study participants and their parents/caretakers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, J., Ma, S. Identification with Buddhism among young Chinese Indonesians: multicultural dynamics and generational transitions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 973 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02494-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02494-0