Abstract

This article examines why food delivery platform workers evaluate their job quality as high despite known drawbacks of this type of employment. Using qualitative data obtained from 20 semi-structured interviews conducted with couriers in Slovenia, the study employs a job quality model consisting of four distinct components (psychological well-being, social satisfaction, economic stability, and health and safety) as a conceptual framework used to determine which elements contribute most to the general job quality evaluation. Findings show that couriers often acknowledge the financial challenges and potential health and safety risks associated with their occupation but are willing to overlook some of these drawbacks due to how highly they value the autonomy, freedom and favourable work-life balance platforms offer. This article argues that platform companies, characterised as permissive entities which still hold a significant amount of power over the labour process, take advantage of the workers’ desire for autonomy and the large worker turnover to continue precarious employment practices. This is additionally fuelled by poor management practices and interpersonal relationships in traditional employment, which often push workers into platform work with no human supervisor, where they can “be their own boss”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid expansion of the platform economy has opened questions on the quality of jobs it creates. Most platform companies perform regular internal job satisfaction surveys which tend to show high job satisfaction levels among platform workers. As platforms are typically reluctant to share precise survey data with policymakers and researchers to allow for their independent job quality evaluations, the questions of job quality are the driver behind numerous external evaluations as well. These studies show that platform workers, despite public concern regarding the precarious nature of their jobs, including inadequate compensation and limited social security, often hold a positive view of their jobs (see Fieseler et al. 2019; Krzywdzinski and Gerber, 2021). This is typically attributed to the seemingly flexible nature of platform work, as well as the absence of a direct supervisor.

When studying the job quality within the platform economy, it is essential to understand the heterogeneous nature of this relatively new form of work. Platform work can be mediated through online web-based platforms or location-based platforms (De Groen et al. 2016; Hauben et al. 2020); it can include higher-skilled workers, such as programmers or graphic designers, or lower-skilled workers, who often work as micro taskers, drivers or couriers (De Groen and Maselli, 2016); and it can be initiated either by the platform, the client or the worker themselves (Eurofound, 2018). This paper focuses exclusively on location-based food delivery platform work, which limits the application of findings to all other groups of platform work.

Platforms, those offering food delivery included, have disrupted the traditional workplace dynamic by establishing a triangular relationship in which they intermediate between those who perform a certain service (workers) and those who request and use this service (users) (Mendonça et al. 2022). When platforms characterise their activity as mere intermediation, they try to justify their business model which is based on hiring independent contractors who are paid on a piece-rate basis (Stewart and Stanford, 2017), who provide and maintain all space and equipment required for them to perform their tasks (ibid.) and who are subject to algorithmic management (Kenney and Zysman, 2016) set in place to control the platform’s globally dispersed workforce and motivate it to perform tasks well (Wood et al. 2019). In this sense, we can see a contrast between flexibility, which must be present for platforms to justify their business model, and control, which is essential for platforms to maintain the quality level of their services.

Given the disparity between widespread scepticism and allegations of job insecurity on one hand, and the notably positive assessments of job quality among platform workers on the other, this article poses two main research questions. Firstly, which job quality dimensions contribute most to a positive job quality evaluation? Secondly, does job satisfaction vary from platform to platform, and what platform practices have the biggest impact on the couriers’ job satisfaction?

This article begins by deepening the conceptualisation of platforms as permissive potentates (Vallas and Schor, 2020). In the continuation, it focuses on the question of job quality in relation to platform work and shows existing literature that answers the question of why people enjoy jobs the public often perceives as bad. Then, it explains the methodology and the Slovenian platform work context, followed by the findings. The final section discusses the article’s main findings.

Platforms as permissive potentates

The emergence of the platform economy, onset by the founding of platforms like Uber and Amazon Mechanical Turk, was to a large extent fuelled by the economic crisis of 2008, which pushed millions of job-deprived workers into the sphere of non-traditional employment. Combining the workforce abundance with the rapid developments in information communication technologies, the rise of platforms was inevitable. Throughout the last decade, they have proven themselves to be a disruptive force in several industries, such as transportation (with platforms like Uber) and hotel services (with platforms like Airbnb) (De Groen et al. 2016). In 2021, digital labour platforms, the subject of this paper, attracted more than 28 million workers in the EU-27 area alone, and the number is expected to increase to more than 42 million by 2030 (European Commission, 2021).

Their growth can, to a large extent, be attributed to the specific platform business model, which heavily benefits from externalizing costs that otherwise occur by either employing workers or owning fixed capital - this allows platforms to expand at incredible speed compared to companies with traditional business models (Vallas and Schor, 2020).

In addition to the changes in business model, platforms have also transformed the traditional employment relationship standards and labour processes (ibid.). Platforms, as opposed to traditional employers, permit their workers to select the location, time, and to some extent the method of their work, but continue to hold a significant amount of power over the key elements of the labour process, such as price levels, task allocation and ultimately the profits (Vallas and Schor, 2020). This dichotomy is best reflected in the conceptualisation of digital labour platforms as “permissive potentates” (ibid.)—entities which offer flexible employment but use algorithms to supervise the seemingly flexible workforce (Mendonça and Kougiannou, 2023).

The first change in business model can be observed in the fact that platforms adopt a much more relaxed recruitment process where the barrier to entry is low. This practice has created an extremely heterogenous workforce, both in terms of socioeconomic and labour market positions of workers, as well as their dependence on income earned within the platform economy (Vallas and Schor, 2020). The heterogeneity of the platform workforce (in terms of economic dependence, motivation and similar) does not only have an impact on how workers perceive their job quality (Schor and Attwood-Charles, 2017) but also on how likely they are to agree on the demands to improve their working conditions (Mendonça and Kougiannou, 2023). The former will be further examined in the continuation of this paper. In addition to the lower barrier to entry, platforms have also “opened” the standard employment relationship by, for example, allowing workers to work for a competitive platform as well (Vallas and Schor, 2020).

Digital labour platforms have also replaced the traditional hierarchical supervisory structures with other means that allow them to oversee how workers perform their tasks—while they do not control workers directly, they set in place other monitoring mechanisms, such as location monitoring and client ratings (Vallas and Schor, 2020). These mechanisms, while essential in monitoring a globally dispersed workforce, are often easily circumvented in some types of platform work, such as online micro-tasking (Wood et al. 2019).

Bad job reputation, good job quality?

With platform work’s unstoppable growth come questions on the quality of jobs it creates. The concept of job quality has been evolving into one of the most important policy objectives of the European Union since the introduction of the European Employment Strategy in 1997 and the Lisbon Strategy in 2000 (Eurofound, 2021). In research, there is a consensus on the multidisciplinary nature of the concept (Martel and Dupuis, 2006; Kalleberg, 2011; Findlay, Kalleberg and Warhurst, 2013; Goods et al. 2019; European Commission - Directorate-General for Employment Social Affairs and Inclusion et al. 2020), with different disciplines focusing on its different aspects - economists tend to focus on payment, sociologists on autonomy at work, and psychologists on job satisfaction (Kalleberg, 2011; Findlay, Kalleberg and Warhurst, 2013).

Job quality models and frameworks have been formed by most international organizations. Eurofound’s job quality model, for example, is measured at the level of the job and includes the elements of work intensity, social environment, earnings, prospects, physical environment, working time quality, skills, and discretion (Eurofound, 2021). Other models, such as the one formed by ILO, are measured on a national level and include elements such as the presence of work that should be abolished (such as child labour or forced labour), the presence of social dialogue, workers’ and employers’ representation and similar (ILO, 2013). However, authors (see Goods et al. 2019; Wei and Macdonald, 2021) emphasise that when it comes to the job quality of platform work, the specifics of this type of work, such as the great rating-based power of clients and the role of algorithmic management, require new, different, or at least adapted approaches.

Such an approach can be observed in Fairwork, a project based at the Oxford Internet Institute which rates the working conditions within the platform economy on the level of a platform, by assigning scores to individual platforms according to the five principles of fair work, which include fair pay, fair conditions, fair contracts, fair management, and fair representation (Fairwork, 2022). Platforms are assigned a score from 1 to 10 based on desk research, worker interviews and surveys, as well as interviews with the management of the platform company in question.

Wei and Macdonald (2021) created a platform job quality model based on 24 interviews with platform workers in China and used it as a basis for a survey with 500 location-based platform workers. The survey showed that platform workers primarily consider their “income, labour protections, voice and client behaviour” when determining the quality of their work.

Acknowledging the specifics of location-based platform work as well, Goods et al. (2019) evaluated the job quality of platform food delivery work through three dimensions – economic (referring to economic security), sociological (referring to work autonomy) and psychological (referring to enjoyment of work). Through 58 interviews with Australian food delivery platform workers, they found that while workers reported earning insufficient income, they evaluated their autonomy over when, where and how long they work very positively, and stated they find their job enjoyable, mostly due to pleasant social interactions and the outdoor nature of the job. The authors claim that how the workers perceive their job quality is largely dependent on how the job fits their current circumstances and existing alternatives. The individual fit is reflected in the fact that despite expressing discontent about certain aspects of delivery work, most workers felt these negatives were outweighed by the positive sides of their job.

Predominantly positive evaluations of platform work are commonly observed in other research as well. A survey conducted among 203 American microworkers revealed a mostly positive relationship with the platform they work for, mostly due to the belief that the platform offers them an opportunity to earn additional income—the positive assessment was higher in workers who were less dependent on this income source (Fieseler et al. 2019). A similar positive perception of platform work, especially by those not fully economically dependent on the platform, is also mentioned by Krzywdzinski and Gerber (2021), who conclude that the different degrees of economic dependence lead to the fact that “working on the same platform does not necessarily lead to shared work experiences”. Other research shows that income is not the only reason behind the workers’ positive relationship with the platform. Interviews with 55 US American platform food delivery workers and a survey with 955 platform food delivery workers showed that the positive evaluation of their job is based largely on the autonomy and freedom it offers, especially the absence of a physical supervisor (Griesbach et al. 2019). This phenomenon can also be observed in research based on 32 interviews with Scottish gig workers, where Myhill et al. (2021) used Scotland’s Fair Work Framework to assess the quality of platform jobs. Despite objective drawbacks, such as income volatility and a lack of support for workers, a subjective feeling of autonomy, flexibility and security was reported by the workers. Most importantly, the study further confirms the fact that individual characteristics and expectations are essential in how workers evaluate the quality of their jobs.

In Slovenia, platform work is a relatively new phenomenon and not many platforms are currently present on the Slovenian market. This scarcity can be attributed in part to the absence of a legal basis for the entry of ride-hailing platforms (such as Uber) into the Slovenian market. In terms of food delivery platforms, the subject of this study, only two are currently operating in Slovenia - Wolt, which entered the market in 2019, and Glovo, which entered the market in 2021. The Slovenian labor force is to a large extent used to traditional closed employment relationships, which are typically characterized by strong institutional protections for workers, as opposed to market-mediated open employment relationships such as platform work (Kalleberg, 2011), where workers are the ones carrying both the economic risks related to their job, as well as the responsibility for their training and safety (Wood et al. 2019). For these reasons, a large segment of the population perceives platform work as pure precarization of the labor market.

The public has been shifting more attention to the real-life working conditions and challenges of food delivery couriers since the formation of their union in April 2023. The union managed to attract over 150 couriers by May of the same year (RTV SLO 2023). While there is currently no exact data on the number of active couriers in the country, the union estimates there to be about 1000–1200, which means approximately 10% are currently involved in union activities. According to a 2022 study, it is estimated that couriers predominantly work as independent contractors (80%) or as students (20%) (Franca and Domadenik, 2022). According to union representatives, more exploitative work forms have started to appear in recent years (such as the trend of companies who hire workers otherwise unable or unwilling to obtain the status of an independent contractor and give them the opportunity to work as couriers in exchange for a share of their total income), but no such case was identified during this study. Additionally, as the interviews were conducted in April of 2023, prior to the union’s formation, no union representatives or members were included in the interview sample.

Methodology

A job quality framework

Drawing from existing literature and the belief that the examination of platform work’s job quality, particularly location-based platform work such as delivery, should reflect its unique characteristics, we devised a model that comprises four main dimensions of job quality. The model is similar to the above-described model by Goods et al. (2019), with a separate dimension of workplace health and safety added. The reason for this addition is the fact that location-based platform workers, such as delivery workers, are exposed to more threats to their health and safety due to the largely outdoor nature of their jobs and the time spent in often dangerous traffic. The original model, as many others, incorporates the questions of health and safety into the economic component of job quality, as it is understood that the impact of workplace injuries is a primarily economic one since injuries are tied to the worker’s loss of income. The importance of this element is confirmed by interviews conducted with Chinese platform workers, which showed that, besides salary, welfare and voice at work, health and safety were among the top three factors workers pointed out as having an impact on their job quality (Wei and Macdonald, 2021).

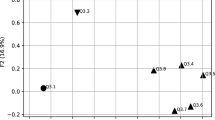

This model, presented below in Fig. 1, served as a framework for our 20 semi-structured interviews with platform delivery workers, providing us with insightful perspectives on their experiences.

Data collection and analysis

Qualitative data was drawn from 20 semi-structured interviews with platform delivery workers across the 2 food delivery platforms currently present in Slovenia. Data triangulation protocols were followed (Creswell, 2009) and two main sources of data were included – initial general information regarding the working conditions and challenges of couriers were obtained from social media groups and courier posts, and interviews were used to gather actual data on the working conditions of couriers. Data retrieved from social media was used primarily as a means to obtain information regarding work practices in food delivery and to cross-check the information obtained from the interviews (as seen in Mendonça et al. (2022)).

A maximum variation purposive sampling was used to ensure the study both documents diversity and identifies the common patterns across the diversity (Patton, 2014). In forming the sample, three goals were set – gender, age and employment status diversity. A gender-diverse sample was deemed essential due to existing literature which shows the female platform work experience can be different than that of male couriers (see Milkman et al. (2020). Age diversity was important as research shows how an individual’s life stage can have an effect on how workers perceive their job quality (see Goods et al. 2019). Lastly, the aim was for the sample to include couriers working as independent contractors and those working through a student referral to see whether this status had an effect on how couriers evaluate their job quality. The first goal, that of a gender-balanced sample, was not reached due to a general underrepresentation of women in this profession, a fact confirmed by the participants themselves. The female participants even explained that the lack of female representation in the profession was a deterring factor in their decision to start working as couriers. The final sample thus consisted of 13 men and 7 women. The goal of an age-diverse sample was reached, and it included couriers between 19 and 39 years of age, the average participant age being 27,3 years. In terms of employment status, the goal was reached, and the sample included 12 independent contractors and 8 students. 10 couriers were working for the platform full-time, while 10 saw it as additional income and worked part-time.

Table 1 contains the sample description. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the author’s institution prior to the commencement of interviews.

The interviews with an average duration of 45 minutes were conducted in a virtual setting with the use of video conferencing technology or telephone. The latter approach was used to maximize participation rates, as telephonic interviews are often perceived as more convenient and less intrusive in the eyes of participants (Farooq and de Villiers, 2017). While street intercepts are often used in similar research, they can lead to incomplete or interrupted interviews as workers must leave when they are assigned new deliveries (see Goods et al. 2019), which is why the method was decided against, prioritizing the quality of full in-depth interviews rather than their potentially larger quantity. Interviews were conducted until saturation (Yin, 2014), which was reached by the 20th interview.

By using NVivo (Version 12) for qualitative data analysis, the data was subjected to open coding guided by thematic analysis principles, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Thematic analysis is a method which allows the identification, analysis and reporting of patterns or themes within the dataset (ibid). All participants’ views were given equal treatment during interview data analysis, regardless of their incidence.

Findings

Economic dimension of job quality

When discussing the economic dimension of job quality, the goal was to see how workers assess the level, stability and predictability of their earnings, as well as how the quantity of unpaid time (when they wait for deliveries), and the equipment maintenance costs influence their job quality assessment.

When it comes to the level of earnings, most participants agreed their income should be higher, especially in the context of the current cost-of-living crisis. When asked about their opinion on the formation of a courier union, for example, one courier stated:

“I think there is a need for a union, because gas prices keep increasing but our wages are the same as they were when it was cheaper.”

(P3)

When asked about the consistency and predictability of their earnings, the delivery workers had vastly different experiences. While some felt confident in the approximate consistency of their earnings, others reported feeling worried about the future, as they know a consistent number of deliveries is never guaranteed in this job. This was less common with younger delivery workers, especially students, who can still rely on their parents for financial support, as well as with the workers for whom delivery is not a primary source of income. This is consistent with a large strand of literature from this field (Myhill et al. 2021; Krzywdzinski and Gerber, 2021, Schor and Attwood-Charles, 2017). Additional concern was expressed by the workers on one of the platforms which announced a change in their payment system less than a month ago – while its economic consequences were difficult to assess at the time, the general concern is evidence of the inherent unpredictability associated with this form of employment.

The participating couriers did not complain about excessive unpaid wait times but did express concern about the fact that an influx of new couriers has led to a decline in their earnings. Two of the couriers stated:

“When new couriers arrive, there are too many of us. The system distributes the orders so that everyone has approximately the same amount, which means we all get fewer orders and that is a problem.”

(P8)

“Some couriers are unhappy that at one point, the company hired a lot of new people and the regular couriers are now making less money. They used to get a lot of money from delivery, and now this has decreased significantly.”

(P14)

This revealed a significant conflict of interest between the workers and the platform after a critical mass of workers is reached. The platform’s interest is to decrease delivery times, which is only possible if the network of couriers is large and spread across the entire delivery area. For the workers, however, especially those with delivery as their primary source of income, new couriers present additional competition which inevitably leads to a decrease in the number of orders they are assigned and consequently in income.

Lastly, and surprisingly, all but 4 participants reported having had no expenses related to the maintenance of their vehicle or equipment. The remaining 4 reported having relatively small expenses, such as repairing or replacing a flat bicycle tire or similar. One courier reported the following:

“I bought some equipment (clothes, winter leggings) but they were minor expenses. I will use these things for exercise anyway.”

(P7)

Social dimensions of job quality

This section aimed to uncover the couriers’ assessments of their level of autonomy and the work-life balance that the job provides, as well as their perspectives on the relationships with the platform, clients, and fellow workers.

All participants agreed that working as a food delivery courier allows them to maintain a better work-life balance, pointing out how traditional employment is less compatible with study or family obligations. A student who works as a courier stated:

“The flexibility isn’t quite as advertised, but it is still better than a regular job. I can’t imagine working a full-time job and passing my college obligations at the same time.”

(P7)

The issue of illusory flexibility was pointed out by several other couriers as well, claiming they feel free and autonomous, but then admitting they do, in fact, adapt their schedule to work the high-demand hours, as working when there are no orders is not profitable at all.

In theory, the nature of delivery work is extremely isolating (see Wood et al. 2018) which is why delivery workers often establish peer networks as support mechanisms (Seetharaman et al. 2021). Our interviews show that some workers enjoy and actively seek contact with their peers, be it through social media groups or in-person meetings during breaks. Others, however, enjoy the job especially due to the absence of social contact. One of the couriers stated the following:

“I have no contact with other couriers, but I like the asocial nature of the job. I like that the app does everything instead of people. Even my boss is an algorithm, and I trust it more than a human.”

(P4)

These statements were common particularly in workers supplementing their income through food delivery, as they already have a social network established at their primary workplace.

All workers pointed out that a responsive and professional courier help centre is extremely important for the quality of their work experience. It is also important for the platform to be willing to adapt to the specific needs of couriers, which one of the platforms seems to be doing better than the other, to the extent of changing the application’s task distribution algorithm upon courier complaints, according to the words of one participant.

“The company really listens to the couriers. Those riding a bike to deliver asked the help centre if they could change the app’s algorithm so that it doesn’t send them to an area of town which is very uphill and difficult to reach by bike, and they did it. They’re really flexible.’

(P2)

This experience was not shared by the workers at the other delivery platform which was described by participants as less willing to adapt. One of the couriers shared the following experience:

“The algorithm sometimes gives you a delivery you cannot do—for example, if I’m delivering by car, I cannot accept an order in the city centre where traffic is restricted and there is no place to park, because I get a fine every time I attempt to do so. The platform was not understanding of this issue at all, and I ended up simply rejecting such orders (three orders from the same restaurant in the city centre), which resulted in me getting removed from the app for an hour.”

(P13)

This shows that similar issues can produce entirely different outcomes in terms of job satisfaction and that the outcomes are heavily dependent on which platform the couriers work for. This is particularly interesting, as it shows how despite the absence of a direct human supervisor, good interpersonal relationships with the platform are still essential in forming the work experience, and how despite the heavily automated nature of platform work, it is the people who have the power to modify the algorithms in the couriers’ favour.

When it comes to their relationship with clients, delivery workers all claimed to have predominantly positive client interactions. Negative interactions are rare due to how proactively the platform’s call centre informs customers of potential delivery delays, ensuring that the delivery workers are not subjected to undue blame or criticism.

“I’ve never had a problem with a client. What you give is what you get, and I always greet them and wish them a nice meal. I’ve been 90 minutes late before, but when you’re running this late, the help centre has already contacted the client and explained the situation. When I finally arrived and apologized, they said it’s not a problem. I’m surprised at how positive these experiences are, because I work in customer service and know how impatient customers can get.”

(P4)

Their interaction with their wider social environment is more complex. When asked about whether they sometimes feel ashamed of their job or stigmatized by their environment, responses could generally be divided in three categories. One third of workers felt no shame or stigma related to their job as food delivery workers:

“No, I didn’t have a feeling of being stigmatised. I don’t care because I know that I’m making money. I’m not embarrassed at all.”

(P5)

Another third claimed feeling no shame, but noticing patronizing looks or comments on the street or among their peers:

“I don’t think it’s a shameful job, but I did get into a situation where I met someone I know, and I got a strange reaction from their side, as if the person was feeling sorry for me. Some people look at these jobs that way. While I don’t care that much, I did notice that some other couriers wear scarves all over their face so you can’t even see who they are. Maybe they don’t want anyone to recognize them.”

(P14)

The last third felt ashamed of their job and reported feeling as if they should be working more complex or intellectually demanding jobs, mostly due to their achieved level of education, and feeling concerned about how others perceived their job:

“I feel it’s embarrassing to work this job. I’m old and I’ve studied for a long time. After all these years of studying, one would expect to be able to do more complex jobs. I have personal issues with it, maybe it’s my pride. It’s also awkward for me when I’m with friends when they order food and talk condescendingly about couriers. They don’t know I do this job occasionally and it makes me uncomfortable. There’s nothing shameful about this job, but there is a certain degree of stigma”.

(P11)

Another courier confirmed this sentiment by stating:

“I still feel ashamed about working this job, but I try not to dwell on it. Maybe it’s a little easier for me now, but I still feel it, because the job isn’t considered “suitable for someone with my potential”. There’s a shame and a stigma.”

(P12)

Psychological dimensions of job quality

In this section, workers were asked about the level of enjoyment and stress stemming from their job, as well as how much (in)security they feel due to its precarious nature. Participants who were working as part-time couriers to earn additional income were also asked about how they cope with multiple job juggling.

Almost all participants evaluated the psychological dimension of their job very highly and mostly reported finding it very enjoyable. Couriers on bicycles were particularly satisfied with the outdoor nature of the job, some even viewing it as “paid exercise”.

“I like cycling, the bike has been my means of transport around Ljubljana for 10 years. Why not make some money while doing it?”

(P7)

Others stated the enjoyment stems from the absence of a human supervisor, which they considered to be a source of stress in their previous (traditional, non-platform) employments.

When queried about the degree of stress stemming from their job, over half of the participants responded in the negative. However, when stress does arise, traffic emerged as its predominant source. Other stressors included the pressure to work in extreme weather (extreme heat, cold or rain), the time pressure of delivering several orders in a row or complications arising from the application’s option of paying for orders in cash.

“Cash payment is now possible. The customer pays you; you take the cash to a gas station to transfer it to the platform. If you do that, you get more deliveries. If you don’t, you have less. For me, it was a no brainer. It takes you 5 to 10 min; you just need to find a gas station.”

(P6)

Managing cash payments was not considered difficult by the participants, but it does place additional responsibility on the couriers, who must ensure they have the appropriate amount of change, that they charge clients with the correct amount and then successfully transfer the cash to the platform company.

To our surprise, workers with two jobs expressed no stress arising from multiple job juggling, as food delivery platforms enable them to log on and off as they wish, meaning they can simply not log on if they have obligations related to their primary employment.

A health and safety dimension of job quality

In this segment, we were most interested in whether couriers experienced health deterioration due to their job, whether they have access to essential infrastructure and sufficient breaks, whether they have undergone health and safety training and whether they use appropriate safety equipment during their work.

All 20 workers denied experiencing any kind of long-term health deterioration due to their job but did complain of occasional pain and tiredness, especially when delivering with a bicycle. While the two platforms do not provide any essential infrastructure (such as toilets or drinking water), the workers do not find this problematic and have had no problems using these services in restaurants they deliver from. Most workers also stated that due to the flexibility and autonomy of this job, they are free to take as many breaks as needed but did notice some of their peers work extensive hours while they attempt to reach their daily income goals.

All participants confirmed the fact that the platforms they work for have never organized any kind of workplace safety training, and some couriers believe such training would be beneficial. Only 10 of the 20 participating delivery workers reported wearing appropriate safety equipment during their work, such as helmets when riding a bicycle, motorbike, or electric scooter.

“You do get a helmet, but not all cyclists use it. I wear a cap. The people riding a motorcycle of course wear their helmets.”

(P1)

This is particularly problematic when we consider the fact that 13 out of the 20 participants have experienced some form of a traffic accident, be it due to contact with another vehicle (6 participants) or due to a slippery and uneven surface (7 participants). This is partly attributed to how much time they spend in traffic, but also to the fact that the delivery platforms’ algorithm determines the appropriate delivery time for each order, pushing the couriers to speed to keep up with the countdown on their mobile phone. In trying to do so, or simply trying to finish an order as soon as possible to get a new one, workers often disregard traffic rules (as seen in Sun, 2019; Mendonça et al. 2022). In our case, as many as 16 participants admitted to violating traffic rules often, mostly by riding bicycles on sidewalks, driving in the opposite direction in one-way streets, running red lights when they feel it is safe, speeding or parking where it is not allowed. Two of the couriers described their experience like this:

“I knowingly violate regulations. Sometimes my fines could probably cost me several thousand euros. I cross solid lines, red lights, and so on. I do feel guilty about the fact that I keep doing foolish things on the road all the time.”

(P2)

“I push the limits and often drive above the speed limit so I can get to my goal quickly. I take the road from point A to point B, and the app tells me it will take me 5 minutes, so of course I go fast. In case I would get stopped by the police, I know I would be the one who would have to pay the fine, not the platform. They warn you to drive carefully, but at the same time, the minutes are ticking away on your phone, so there is definitely pressure.”

(P5)

Discussion and conclusions

This article connects to a wide discussion on the topic of job quality perception within food delivery platform work and factors which make the job attractive for couriers. The first research question aimed to explain what job quality elements contribute most to a positive job quality evaluation among couriers.

Throughout the interviews, it was observed that platform workers are not ignorant of the drawbacks of their job but evaluate their job quality as high regardless. This shows that although all four components contribute to the workers’ evaluation of job quality, their significance varies. Among all the job quality components we defined above, it appears that the sociological component, particularly workplace autonomy, and the psychological component, especially the level of enjoyment stemming from the job, have the greatest influence on a positive assessment of job quality. This does not suggest that income level, security, and workplace health and safety are irrelevant to platform couriers. Instead, it suggests that workers are often inclined to overlook some drawbacks because of their favourable view of not having a physical supervisor, and the ability to control when, where, and to some degree how they work.

This is particularly noticeable in a significant number of individuals who engage in platform work and enjoy it primarily due to a negative experience in their previous traditional, non-platform employment. Several participants reported previously experiencing workplace mobbing and micromanagement, which resulted in a sense of relief and reduced stress when transitioning to platform work and becoming “their own boss”. This suggests that adverse experiences in traditional employment may have a significant impact on an individual’s decision to pursue platform work, a dynamic which could be researched in the future as well. Additionally, the dynamic opens important questions on the future of traditional employment and how jobs will need to adapt to remain attractive to a workforce which increasingly seeks freedom, autonomy, and a sense of independence in employment relationships. This will be particularly important in contexts where platforms have the power to usurp essential workers, such as healthcare workers, who, in some countries, are already leaving the public healthcare system to offer their services on digital platforms in order to escape the poor working conditions and low pay they receive. Retaining these groups of workers will be crucial for the uninterrupted provision of the many essential services which could become platformised in the future.

The second research question was whether there are differences in job satisfaction from platform to platform, and what platform practices are most relevant to the couriers’ job satisfaction.

The interviews revealed a vastly different work experience and consequently a different evaluation of job quality depending on which platform the couriers work for. The difference in job quality evaluations across platforms is consistent with existing research, such as in Griesbach et al. (2019), where couriers were less satisfied with the platform that more closely mimicked the traditional employment relationship, specifically by organizing work around shifts and giving more active couriers the opportunity to fill them prior to all other workers. Krzywdzinski and Gerber (2021) also state that platform specifics must be taken into account when explaining the variety of job quality evaluations among workers, and our conclusion is in line with this. In our sample, this same phenomenon of platforms mimicking traditional employment relationships was criticized for two reasons. Firstly, the workers believed this system decreased worker autonomy and the flexibility platforms typically advertise in their recruitment process. Secondly, the platform using the shift system gave shift-selection priority to highly rated couriers, but the rating system it based on was considered lacking in transparency by the majority of the workers on this platform.

The other reason behind the difference in job quality evaluation across the two platforms was the difference in the quality of support offered to the couriers, with one of the platforms being significantly more responsive and supportive than the other. Other research supports the idea that platform workers value a solid support system and tend to feel abandoned when they do not receive it (Myhill et al., 2021). This ultimately shows that there is no unique platform work experience, and that a myriad of factors determines how couriers evaluate their job quality.

Due to the inherently transient nature of gig work, however, which is often characterized by high worker turnover rates, a longitudinal study that examines job quality assessments over an extended period of time would be invaluable in providing a more comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon.

Data availability

The data presented in this study is available on reasonable request from the author.

References

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706QP063OA

Creswell JW (2009) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed-Method Approaches. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

De Groen W, Maselli I, Fabo B (2016) The Digital Market for Local Services: A one-night stand for workers? An example from the on-demand economy. CEPS Special Report, No. 133. CEPS, Brussels

De Groen WP, Maselli I (2016) The Impact of the Collaborative Economy on the Labour Market. CEPS Special Report No. 138. CEPS, Brussels

Eurofound (2018) Platform work: Types and implications for work and employment-Literature review. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/system/files/2019-12/wpef18004.pdf. Accessed 13 Jan 2023

Eurofound (2021) Working conditions and sustainable work: An analysis using the job quality framework Challenges and prospects in the EU. https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/en/publications/2020/working-conditions-and-sustainable-work-analysis-using-job-quality-framework. Accessed 12 Mar 2023

European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, Barcevičius E, Gineikytė-Kanclerė V, Klimavičiūtė L et al. (2021) Study to support the impact assessment of an EU initiative to improve the working conditions in platform work: final report. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/527749. Accessed 31 Mar 2023

European Commission - Directorate-General for Employment Social Affairs and Inclusion, De Groen W, Lhernould JP, Robin-Olivier S (2020) Study to gather evidence on the working conditions of platform workers: final report. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/26582. Accessed 17 Feb 2023

Fairwork (2022) Location-based Platform Work Principles. https://fair.work/en/fw/principles/fairwork-principles-location-based-work/. Accessed 17 Sep 2023

Farooq MB, de Villiers C (2017) Telephonic qualitative research interviews: When to consider them and how to do them. Meditari Accountancy Research. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-10-2016-0083

Fieseler C, Bucher E, Hoffmann CP (2019) Unfairness by Design? The Perceived Fairness of Digital Labor on Crowdworking Platforms. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10551-017-3607-2

Findlay P, Kalleberg AL, Warhurst C (2013) The challenge of job quality. Human Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713481070

Franca V, Domadenik P (2022) Raziskava: Delo na domu in platformsko delo. https://www.dostojnodelo.eu/images/knjiznica/PDF/Skupno_porocilo_o_raziskavi_Delo_na_domu_in_platf_delo_F.pdf. Accessed 17 Dec 2022

Goods C, Veen A, Barratt T (2019) Is your gig any good? Analysing job quality in the Australian platform-based food-delivery sector. Journal of Industrial Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185618817069

Griesbach K, Reich A, Elliott-Negri L et al. (2019) Algorithmic Control in Platform Food Delivery Work. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119870041

Hauben H, Lenaerts K, Wayaert W (2020) The platform economy and precarious work. Publication for the committee on Employment and Social Affairs, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/652734/IPOL_STU(2020)652734_EN.pdf

ILO (2013) Revised Office proposal for the measurement of decent work - indicators. https://www.ilo.org/integration/resources/mtgdocs/WCMS_115402/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 28 Nov 2022

Kalleberg AL (2011) Good jobs, bad jobs: the rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s to 2000s. Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Kenney M, Zysman J (2016) The Rise of the Platform Economy. Issues in Science and Technology. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309483265_The_Rise_of_the_Platform_Economy

Krzywdzinski M, Gerber C (2021) Between automation and gamification: forms of labour control on crowdwork platforms. Work in the Global Economy. https://doi.org/10.1332/273241721X16295434739161

Martel JP, Dupuis G (2006) Quality of work life: Theoretical and methodological problems, and presentation of a new model and measuring instrument. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11205-004-5368-4

Mendonça P, Kougiannou NK (2023) Disconnecting labour: The impact of intraplatform algorithmic changes on the labour process and workers’ capacity to organise collectively. New Technology, Work and Employment. https://doi.org/10.1111/NTWE.12251

Mendonça P, Kougiannou NK, Clark I (2022) Informalization in gig food delivery in the UK: The case of hyper-flexible and precarious work. Industrial Relations. https://doi.org/10.1111/IREL.12320

Milkman R, Elliott-Negri L, Griesbach K et al. (2020) Gender, Class, and the Gig Economy: The Case of Platform-Based Food Delivery. Critical Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0896920520949631

Myhill K, Richards J, Sang K (2021) Job quality, fair work and gig work: the lived experience of gig workers. International Journal of Human Resource Management. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2020.1867612

Patton MQ (2014) Qualitative Research & Evaluation Method. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

RTV SLO (2023) Dostavljavci Wolta in Glova so drugič stavkali. https://www.rtvslo.si/gospodarstvo/dostavljavci-wolta-in-glova-so-drugic-stavkali/669620. Accessed 26 May 2023

Schor JB, Attwood-Charles W (2017) The “sharing” economy: labor, inequality, and social connection on for-profit platforms. Sociology Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/SOC4.12493

Seetharaman B, Pal J, Hui J (2021) Delivery Work and the Experience of Social Isolation. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449138

Stewart A, Stanford J (2017) Regulating work in the gig economy: What are the options?. The Economic and Labour Relations Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/1035304617722461

Sun P (2019) Your order, their labor: An exploration of algorithms and laboring on food delivery platforms in China. Chinese Journal of Communication. https://doi.org/10.1080/17544750.2019.1583676

Vallas S, Schor JB (2020) What Do Platforms Do? Understanding the Gig Economy. Annual Review of Sociology. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-121919-054857

Wei W, Macdonald IT (2021) Modeling the job quality of “work relationships” in China’s gig economy. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources. https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7941.12310

Wood A, Lehdonvirta V, Graham M (2018) Workers of the Internet Unite? Online Freelancer Organisation Among Remote Gig Economy Workers in Six Asian and African Countries. New Technology, Work and Employment. https://doi.org/10.1111/ntwe.12112

Wood AJ, Graham M, Lehdonvirta V et al. (2019) Good Gig, Bad Gig: Autonomy and Algorithmic Control in the Global Gig Economy. Work, Employment and Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018785616

Yin RK (2014) Case Study Research Design and Methods, 5th edn. SAGE Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding author was responsible for all aspects of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval number 4264-22-5/23 was obtained from the Commission of the University of Primorska for Ethics in Human Subjects Research (KER UP).

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Švagan, B. Understanding the paradox of high job quality evaluations among platform workers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 977 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02477-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02477-1