Abstract

This semester-long qualitative case study, spanning 4 months, focused on an English reading course in which 20 university English-as-a-foreign-language readers were instructed to engage in web-based collaborative learning outside of class. The study drew on data resources including interviews with students, field notes on their web-based collaborative learning practices, and students’ written reflections. A thematic analysis of the data sources shows that the positivity of student readers’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning (i.e., about web-based collaborative platforms and reading activities) changed over time but ultimately became stably positive. The change was found to be related to the interactions between their beliefs about web-based collaborative platforms and their beliefs about reading activities over time. The students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were also found to be sensitive to factors regarding the students’ learning over time, including their prior learning experiences and their ongoing learning experiences. In the process, the students’ web-based collaborative learning practices were primarily driven by their positive beliefs and constrained by their negative beliefs although additional factors emerged over time from their learning process and intervened in the relationship between their beliefs and their learning. The implications of these findings on how to best engage students in web-based learning are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Web-based learning (WBL) is a type of technology-based learning carried out through web resources (e.g., web platforms or Internet-related audio–visual or textual resources) (Cook, 2007; Zhang, 2021). It features multiple dimensions of technological affordances that may be missing from traditional in-class or out-of-class learning (Skylar, 2009). For example, unlike in traditional in-class learning, students can overcome the constraints of time and place through WBL (Bernard et al., 2004). They can learn by themselves through web resources (e.g., audio–visual resources or online information), any time and from anywhere, or collaborate with their peers (e.g., through web platforms) (Skylar, 2009). In particular, the type of WBL known as web-based collaborative learning occurs on an Internet-supported collaborative platform through which learners (e.g., language learners) can synchronously or asynchronously share knowledge and learn from each other (Iyamuremye et al., 2023; Zhang and Zou, 2022). The technological affordances of web-based collaboration enable students to assist or be assisted by others to gain the necessary subject knowledge or complement their in-class learning (Su and Zou, 2022). As such, WBL is a common addition to—or even replacement for—students’ traditional learning (Bernard et al., 2004), such as language learning (Zhang, 2021), especially at times when face-to-face learning is constrained by natural disasters such as a pandemic (Tümen Akyıldız, 2020).

The value of WBL has been highlighted by research on students’ cognitive levels (e.g., Ahmed, 2022; Alhamami, 2019), especially regarding their beliefs (i.e., their evaluative stances) about learning (Borg, 2001). In general, positive beliefs drive students’ practices, while negative beliefs diminish their passion for practices (e.g., their use of web platforms and literacy activities) (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011; Lee and Lee, 2014; Lobos et al., 2021). Further, students’ beliefs reify themselves in practice and dynamically affect students’ practice (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011; Han, 2017). However, research on students’ beliefs about WBL (e.g., in a university English-as-a-foreign-language [EFL) context) has primarily adopted a quantitative approach, clustering around the correlation between students’ beliefs and their learning (e.g., Alhamami, 2019; Koraneekij and Khlaisang, 2019). Hence, there is limited qualitative understanding of the nuances of students’ beliefs, such as how and whether such beliefs change over time and how they are related to practices; thus, qualitative studies are required to fill this gap.

Among existing qualitative studies of WBL, researchers have either used a single source of data (e.g., interviews) to elicit students’ beliefs retrospectively (e.g., Alhamami, 2019) or multiple data sources obtained over a short period, such as 8 weeks (e.g., Ahmed, 2022). Such qualitative studies have been constrained by the limitations of the data sources used or the timespan of the research. In all, the field of WBL requires more qualitative research that uses multiple sources of data and tracks students’ beliefs over time to gain a nuanced understanding of how such beliefs manifest themselves in relation to the process of WBL.

To enrich our understanding of students’ beliefs about WBL, the current study adopted a qualitative approach to investigate university EFL student readers’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning. Insights from this study are expected to support researchers and educators in further understanding or buttressing students’ cognitive behaviors in relation to WBL and promoting WBL as a key source of learning.

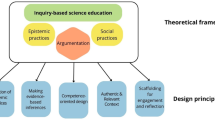

Literature review

Learners’ beliefs as a factor-sensitive construct interacting with practice

Students’ beliefs about learning are conventionally understood as their evaluative stances toward their learning activities (Borg, 2001). As Borg (2001) noted, “[A] belief is a proposition which may be consciously or unconsciously held, is evaluative in that it is accepted as true by the individual” (p. 186).

Students’ beliefs are not stable, being primarily shaped, developed, or reconstructed by their past and ongoing learning practices; thus, their beliefs are sensitive to their past and present factors (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011). For example, new beliefs may emerge from students’ ongoing practices in the learning context to further motivate their learning (Han, 2017). Students may also change their beliefs during their learning when they encounter challenges or feel unbenefited in practice (Fives and Buehl, 2012). Beliefs about a particular learning activity are also comprised of sub-beliefs, meaning subordinate beliefs pertaining to a main belief of the same domain (Green, 1971). For example, students’ beliefs about EFL reading learning may include their beliefs about what should be learned and what they can learn as EFL readers.

Students’ beliefs could be positive (i.e., illustrated by positive stances), negative (i.e., illustrated by negative stances), or a mixture of positive and negative stances (Alhamami, 2019; Aslan and Thompson, 2021). The positivity of students’ beliefs about a particular learning activity is understandably determined by the outcome of the interactions among the beliefs. For example, if one of a students’ beliefs about using web platforms is positively stronger than the others, the overall effect will be a positive belief about using web platforms.

More importantly, students’ beliefs also influence their corresponding practices (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011). In general, students’ positive beliefs about an activity cognitively buttress their learning, for instance, in the form of motivating their learning behavior (Aslan and Thompson, 2021). By contrast, their negative beliefs generally constrain their corresponding activities in practice (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011). However, such a relationship between students’ beliefs and their corresponding practices may be disrupted, appearing to be dynamic and subject to additional influences arising from the learning context in which students are placed (Aslan and Thompson, 2021; Han, 2017). For example, whereas a student may believe in the importance of a learning task on a web platform, this positive stance may not be represented in their actual practice due to the external or internal factors embedded in the learning context, such as external distractions (Zhang, 2021), the limitation of their knowledge repertoires (Zhu and Wang, 2019), or individual alignment with the learning context (e.g., potential actions taken by the student) (Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011).

Relevant research on WBL

The benefits of WBL, including web-based collaborative learning, have been widely explored in the fields of general education (e.g., Iyamuremye et al., 2023) and language education (Su and Zou, 2022; see Zhang and Zou, 2022 for a review). This line of research has extensively captured diverse affordances of WBL, such as transcending the constraints of time and place in providing a flexible venue for students (Ishimura and Fitzgibbons, 2023), affording interactive learning among participants through peer or teacher mediation (Lam, 2021; Selcuk et al., 2021), and boosting students’ self-efficacy in learning (Kuo et al., 2021).

Although empirical research has been conducted on students’ beliefs about WBL with regard to their practices, studies in this research stream have been predominantly quantitative (e.g., Lobos et al., 2021; Koraneekij and Khlaisang, 2019). For example, Lee and Lee (2014) conducted a quantitative analysis of 136 undergraduate students (pre-service teachers) at a university in South Korea. The authors showed that students’ practical activities (e.g., lesson planning activities) have a positive influence on teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs regarding technology integration. The findings also indicate that factors in the learning context can enhance the positivity of students’ beliefs (e.g., students’ abilities to handle computers). However, findings from this line of quantitative research were concerned with students’ beliefs, practices, and influencing factors at a particular point in time; thus, they did not provide an understanding of the dynamic relationship between students’ beliefs, practices, and influencing factors over time during their WBL.

While qualitative research on WBL could fill the research gap mentioned, relevant studies are limited, especially in the EFL or web-based collaborative learning context. If the few available qualitative studies had drawn on more sources of data, they could have yielded a more detailed understanding of students’ beliefs in relation to WBL, such as the potential dynamics of the relationship during the learning process. For example, the qualitative part of Alhamami’s (2019) mixed-methods research only included interviews with 16 EFL students enrolled in an intensive EFL program at a Saudi university about their beliefs regarding online language learning classes (compared to face-to-face language learning classes). Alhamami found that the students’ beliefs comprised several sub-beliefs and that they held both negative beliefs (e.g., technical problems) and positive beliefs (e.g., the affordances of websites and applications).

Another example of the limitations of extant qualitative studies emerges in Ahmed’s (2022) case study, which, although it used multiple data sources (e.g., stimulated recall interviews, surveys, and class observations), only collected data over eight weeks from an English teaching program offered to international students. Ahmed’s (2022) research findings, however, were illuminating, revealing that the students gradually gained positive beliefs about their web-based collaborative learning through Google products (i.e., Google Docs and Google Drive) and that their positive beliefs were attributed to their positive experiences, which were mediated by additional factors, such as the students’ alignment with the learning environment and personality as well as teacher assistance.

In summary, more qualitative research is needed within EFL settings given the paucity of research in this context to date. In addition, as Ahmed (2022) has highlighted, the field should be expanded by using multiple sources of data collected over a longer period of time, which could yield a greater understanding of students’ beliefs and the relationship between these beliefs and their practices. To fill this gap, the present study adopted a qualitative case study approach, drawing on multiple data sources collected from an EFL reading course at a Chinese university that lasted for one semester (4 months) and focusing on the relationship between the students’ beliefs, practices, and influencing factors. The study was guided by the following questions:

-

(1)

What do EFL student readers’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning look like over one semester?

-

(2)

What factors moderate students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning over one semester?

-

(3)

How are students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning related to their practices in this type of learning over one semester?

It is hoped that, by answering these three questions, this study will further inform the pedagogical adoption of web platforms in similar contexts, especially in terms of addressing students’ belief systems during learning.

Methodology

To answer the research questions, the present study adopted a qualitative case study approach (Duff, 2008) focusing on an EFL reading course (attended by 20 students) as a case and generating an understanding of the research topic of university EFL readers’ beliefs about WBL. A qualitative case study approach allows researchers to use multiple sources of data collected in a particular context over time and explore a phenomenon in depth without the need for a large number of participants across different settings (Duff, 2008). This approach aligns with the current study’s goal of conducting an exploration of how students’ beliefs about WBL develop over time in one particular context rather than seeking generalized findings on the phenomenon.

Research context

The WBL in the current study occurred in an EFL reading course at a Chinese university. For the course, students were instructed to engage in out-of-class participation in web-based collaborative learning over one semester (4 months). A Chinese company developed the Internet-based web platform, with a function similar to Google Docs. In this study, as users in China could not access Google-related services, the instructor chose this web platform because it was freely available. For example, with the Internet-based web platform, students do not need to meet face to face and can choose any place convenient for them to engage in web-based collaborative learning. Students can create texts (such as posing questions and answers; see Table 1) directly on the web platform and edit the texts whenever they want. The web platform allows students to work on their texts at the same time (synchronously) or at different times (i.e., synchronously). It also provides similar functions to Microsoft Word: students can use different colors, fonts, or sizes of their works to mark their texts, revisions, or edits on the web platform, along with the function of inserting external sources (e.g., pictures or snapshots of a reading text). All activities (e.g., posting, editing, or revising texts) are automatically saved on the web platform and immediately visible to each other.

One activity the students were required to complete on the web platform was related to their pre-class reading; they had to pose their concerns/questions regarding a text that was to be taught in the class. As the students were English majors (see the next subsection), the texts used in the reading classroom were academic texts related to linguistics, language acquisition, and cross-cultural communication. This part of the activity was designed to motivate the students to think about the text critically and raise their concerns, especially regarding the text content.

The other task the students were asked to perform was to help each other on the platform—a further push regarding their thinking activities. Students were asked to help each other answer questions and to comment on answers provided by their peers. The second part of the activity provided an additional venue for students to think from various perspectives using diverse approaches; this was achieved in the form of learning from peer comments, addressing others’ concerns, and responding to peer answers.

Students on the web platform interacted with each other throughout the semester, engaging in these two types of activities related to the 10 texts covered within the semester. Students could engage in the activities at any time or place convenient to them. However, they had to complete the activity before the deadline set by their instructor, after which the instructor would also help students go over the activities in class to further address students’ concerns. The details of the activities and other aspects of the study are shown in Table 1.

The web-based collaborative activities were designed to help students critically navigate the text, informed by reading as a process of deconstructing meanings in a text (see Fang et al., 2019). However, as companions, students were also encouraged to help address others’ concerns regarding language or grammar issues if there were difficulties in this regard. Indeed, in pre-tertiary English education, students in China are trained to gain a general idea of a text or the meaning of individual sentences (Zhang, 2021). For the first text, the students were exposed to the teacher’s demonstration of the text before engaging in collaborative activities for the other texts. For all other texts used in the class, the students collaborated before the texts were taught. The purpose was to encourage students’ maximal peer assistance on the platform.

Participants

The students involved in the case were first-semester university EFL students majoring in English. They were all born and raised in China. They had never engaged in WBL before, although they had experienced synchronous online lectures. Prior to this semester, their English learning was primarily based on in-class teaching, which relied heavily on textbooks. Twenty students (named Students 1–20), who were all females, were willingly involved in the current study. All participants gave their informed written consent. The students came from different regions of China and entered the university through China’s college entrance examination (which included an English reading test). The students rated themselves as intermediate English readers. Indeed, while the English test may differ slightly across regions, the students entered the university with almost similar scores on the English test. The English department considered the students’ English proficiency intermediate, based on an English proficiency test held by the department to place students in certain courses, although some students felt that they might be below or above the average level during their web-based collaborative learning.

Regarding their reading literacy, all students were placed in test-driven teaching contexts. Hence, similar to many other EFL reading classrooms at the pre-tertiary level, their prior reading classroom environments had been more targeted at preparing students for high-stakes tests (e.g., university entrance examinations). Thus, along with focusing on learning grammar and vocabulary, the students were trained to focus on the surface meanings of the texts (Zhang, 2021). In other words, their prior experiences differed from the demands of the current environment, where reading centered on the deep meaning of texts, particularly academic texts.

Data collection

The project involved diverse data sources, including semi-structured interviews with students. The interviews elicited students’ verbalized beliefs about WBL, which is a common and primary way of understanding students’ beliefs. The students’ initial beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were retrospectively elicited through the first round of interviews as baseline data (see also Finding section 1). That is, their beliefs about the web-based collaborative platform involved their positive stances toward the operation of the web platform and their neutral and negative stances toward the pedagogical value of the web platform. Their initial beliefs about reading literacy were generally negative. Throughout the semester, each participant was interviewed three times. Each interview lasted around 48 min and was conducted in the students’ first language (i.e., Chinese). The first round of interviews occurred in the middle of the semester when the students had become familiar with the researcher and felt ready and comfortable verbalizing their beliefs. The second round of interviews occurred at the end of the semester. During the first two interviews, prompted by guiding questions, the students were asked to share their thoughts (e.g., “How do you feel about your reading literacy or your use of the platform?”) and observations about their WBL activities or their written reflections (see the additional sources of data mentioned in the following paragraphs). About a month after the second round of interviews, a third round of interviews occurred. These interviews primarily complemented the first two interviews and other sources of data pertaining to the study (e.g., the field notes, which are mentioned below) to help understand the students’ beliefs.

Different from the interviews with the students, students’ reflections, as another source of data, occurred in a written form. Each of them was asked to write two reflective essays during the semester, which were collected at different times that did not coincide with the interviews. One reflective essay was conducted prior to the first interview. This gave the students space to reflect upon their experiences, although they primarily wrote about their reading literacy development and not specifically about WBL. At the end of the semester and prior to the second round of interviews, the students wrote the second reflective essay, which summarized their experiences in the latter half of the semester. Their reflections were written in the first language, with each students’ piece comprising around 2000 words.

Further, the researcher kept field notes about the students’ activities on the web platform throughout the semester. The field notes covered students’ peer-learning activities (e.g., how they helped or interacted with each other) and their self-initiated questions/concerns shared on the web, which arose during their independent learning on the web platform.

Data analysis

Data were simultaneously collected and analyzed, and the ongoing analysis further informed the continuation of the data collection (e.g., follow-up interviews and related questions asked). Inductive thematic analysis was primarily used. The sources of the transcribed or written data were subject to multiple rounds of open coding, and codes related to the study were kept. Table 2 demonstrates how the data sources and analysis address research questions in relation to the students’ Web-based collaborative activities.

In particular, the students’ beliefs, as their evaluative stances, can be analyzed by identifying the language resources in their verbalized statements on their learning (Martin and White, 2005). When identifying language resources, researchers could focus on those in relation to the three components of students’ evaluative stances: language resources expressing their emotions, language resources expressing their judgment of human behaviors, and language resources expressing their assessment of objects (Martin and White, 2005). These linguistic resources could have positive or negative meanings. For example, in the statement “I feel challenged by the use of the web platform”, the student was expressing her evaluative stance by expressing a negative emotion. Similarly, in the statement “The web platform is useful for me now”, the language resource “useful” can be identified as a students’ positive evaluative stance, namely, her assessment of an object. In addition, the three components of students’ evaluative stances could be strengthened or softened, which could also be identified through linguistic resources, such as adverbs or adjectives. In the statement “The web platform is very useful,” very is a typical resource that intensifies a speaker’s evaluative stance (i.e., strengthens the speaker’s assessment of an object).

In addition, students can express their beliefs, as evaluative stances, by opening up to other possibilities or voices (Martin and White, 2005). This also signifies the importance of paying attention to typical linguistic resources, including modal verbs and the collocation of a speaker’s name and reporting verbs (e.g., think, feel, and agree), to further understand students’ beliefs. For example, in the statement “The web platform may be not useful for me, but others think otherwise,” may also indicate that the students’ evaluative stance was not assertive and that the student was open to other stances. The students’ subsequent use of others think further indicates this case. In addition, this dimension could be softened or strengthened and can be unpacked through linguistic resources, such as verbs or adverbs (Martin and White, 2005). For example, others think is weaker than others argue.

As such, students’ beliefs (i.e., their positive, negative, and neutral stances) and language resources (e.g., words that denoted or connoted the students’ evaluative stances) were used to help with open coding (Martin and White, 2005). The inductive process was further refined by examining previous studies related to WBL and students’ beliefs about WBL (e.g., Alhamami, 2019; Bernard et al., 2004; Skylar, 2009) and studies on EFL reading literacy development (e.g., Huang, 2011; Mehta and Al-Mahrooqi, 2015). All the relevant codes were then combined to form categories, which were reexamined several times to avoid missing any key codes and categories pertaining to the studies. The categories were then grouped into themes, along with interview excerpts (IE), excerpts from students’ reflections (RE), and the researchers’ field notes to answer the study’s research questions.

Findings

The findings regarding the three research questions are reported in chronological order because four major themes related to four key phases of the timeline were identified in the semester-long case study. In addition, each major theme provided interrelated answers to the three research questions. As such, when reporting findings, the study did not tease apart answers to the three research questions; instead, for each phase of the timeline, relevant findings regarding the three research questions were reported together under a major theme.

Overall, the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning (mainly comprising their beliefs about using web platforms and reading activities) demonstrated positivity dynamically over time. Their beliefs changed from slightly negative to positive to mixed (i.e., both positive and negative) to stably positive beliefs. The dynamic interaction between the two main beliefs partially contributed to the change in positivity. The altered positivity of web-based collaborative learning over time was also found to concern changing factors that emerged during the students’ learning process. The dynamic change in students’ beliefs also led to their practices fluctuating during their web-based collaborative learning (e.g., disruption of students’ practices due to their negative beliefs about web-based collaborative learning). However, their beliefs gradually became positive and positively promoted their corresponding practices.

The early phase of students’ beliefs: Forms of beliefs, moderating factors, and practices

Over the semester, the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning mainly spanned two domains: their beliefs about using web platforms and their beliefs about reading activities. As Student 3 noted, “The value of the learning is based on my judgment of the platform itself and my reading learning” (IE). Student 7 added, “For the use of the web platform, the value can mainly be seen from its operation and whether it benefits my learning” (IE). Further, the students’ beliefs about using the web platform involved two sub-beliefs: beliefs about the operation of the web platform and beliefs about the pedagogical value of the web platform. Students’ beliefs about reading activities branched out into two main sub-beliefs: one about the reading activities they could handle, as Student 7 shared, “My attitude toward reading is partially dependent on whether I could meet the demands” (RE). This was related to the second sub-belief—about what they should master as university students, which was echoed by Student 13, “My embracement with the reading activities is also sustained by what I think I should achieve as a university student” (IE).

During the students’ initial engagement in web-based collaborative learning, their beliefs about using the web platform were generally neutral, and their beliefs about reading activities were generally negative. The two main beliefs had almost no interaction. The positivity of their beliefs was determined by the sub-beliefs pertaining to the same domain.

Regarding the students’ beliefs about using the web platform, their sub-belief about the operation of the web platform was positive, and their sub-belief about the pedagogical value of the web platform was either neutral or negative. For example, Student 7 pointed out, “I have never used the platform officially, so I had no expectations of it. But I do not think it is complex … Based on my current experiences, it is easy to operate” (IE). Student 9 added, “I was reserved about the value of the platform … I thought maybe it took time to see whether it helps with my reading” (RE). Student 5’s belief was obviously negative: “I did not know what to do on the platform; I also did not like to make my learning public to other classmates” (IE).

The students’ different sub-beliefs (i.e., positive, neutral, or negative emotions about the use of the web platform) manifesting their beliefs about using web-based platforms appeared to be moderated by diverse factors (i.e., the students’ ongoing experiences with the web platform). Student 7 indicated, “Based on my ongoing experiences, it was easy to operate, so I immediately welcomed the use of the platform” (IE). The students indicated that the web platform was user-friendly to operate, a factor in their positive sub-belief in this regard. However, Student 11 said, “I saw that we mostly posed similar questions on the web, so what was the significance of using the platform?” (IE). Student 8 added, “The majority of questions were seemingly not well answered … It may be the beginning of the semester. I guessed we needed to be patient” (IE). The quality of the questions posed and answered in the early phase of the pre-class reading made the students either hold a negative or natural sub-belief about the pedagogical value of the web platform early in the semester.

As such, the students’ beliefs about using the web platform were generally neutral. As Student 11 stated, “The operation and pedagogical value of the platform contributed to my overall understanding of the platform. Regardless, I then continued with the mode of learning as instructed and decided to wait and see” (RE). The generally neutral beliefs suggested the internal interaction of the two sub-beliefs, with some students’ negative sub-beliefs being offset.

Regarding the students’ initial beliefs about reading activities, the sub-belief about the reading activities they could handle was strikingly negative, and the other sub-belief about what they should master as university students was neutral. For example, Student 5 reported, “I feel I could not handle the demands of reading activities now … [They’re] too challenging, and I was not ready for them” (RE). However, Student 6 pointed out, “But I did not have any negative stance about reading literacy itself” (IE). The differences in the positivity of the two sub-beliefs were also related to their past and ongoing experiences with reading literacy. For example, Student 14 shared, “Before entering the university, we focused on the surface meaning of a text, and memorizing structure and vocabulary from a text” (IE). Student 11 pointed out, “I feel there was a gap between what I had learned and what I needed to learn as a reader. But now we have to do reading activities critically” (RE). The difficulty of the reading activities and the inadequate transition from their previous education drove the students’ negative sub-beliefs about the demands of the reading activities required on the platform. However, the students’ awareness of the new institution they were in also led to their empathy regarding the reading standards set for university students, which made them hold neutral beliefs about what they should master as university EFL readers. For example, Student 6 indicated, “As a university student, we need to make breakthroughs in text comprehension, and face it anyway” (RE). Student 6 also added, “How could we be called ‘university students’ if we still learn easy stuff or similar content we learned in high school? If we do not want to be challenged and make further academic progress, there is no need for us to enter university (IE)”.

With the suggested interaction of the students’ two sub-beliefs (one is negative, and the other neutral), their beliefs about reading activities, in general, were negative, which is understandable. This could be explained by Student 14’s remarks: “I felt torn in this situation, but I found myself feeling that the necessity of reading activities could not effectively offset the challenges that the activities themselves brought to me” (IE).

However, the students’ beliefs about using the web platform and their beliefs about reading activities did not interact in the initial phase of their learning. As Student 6 noted, “I just put the reading questions on the web as instructed, but I do not know how to do it better for my reading” (IE). Student 8 echoed, “I had not experienced benefits from the simultaneous use of web and reading activities” (RE). The students’ lack of sufficient experience in navigating WBL made them feel that linking the platform with reading activities was not necessary. Accordingly, the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning, which were a combination of the two main beliefs, were slightly negative at this stage. As Student 1 said, “Overall, I feel less than neutral about web-based learning” (IE).

At this stage, the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were mapped to their practice through their beliefs about web platform use and reading activities (including their respective positivity or internal interaction). That is their beliefs about web platform use and the reading activities, which had no interaction with each other, exerted their influence on the students’ practices separately. As the field notes show, the students all used the web platform to complete the compulsory activities (i.e., posing critical questions), echoing their beliefs about the web platform (i.e., their neutral stance). In addition, recall that their beliefs about the reading activities were slightly negative in general. Although in practice they posed their critical questions, they did not participate in the voluntary activities (e.g., helping each other) at the beginning of the semester, and some only finished the activities within moments of the deadline (field notes). Their negative beliefs were not sufficiently strong to allow the students to escape from their learning tasks. As Student 8 affirmed, “I am a student, and I have to do the activity the teacher asked me to do” (RE). When the students’ negative beliefs exerted power on their practices, such power was also subject to the mediation of the students’ context (i.e., teacher–student culture), and this mediation was especially obvious in the very early phase of their learning in the course.

The second phrase: Students’ changing beliefs and their continued practice in relation to moderating factors

The students’ beliefs about using web platforms and their beliefs about reading activities changed along with their extended exposure to the learning context. This transformation was observed at the level of positivity of the two main beliefs and at the level of interaction within or between these two main beliefs.

Recall that the students’ beliefs about using the web platform included their sub-beliefs about the operation of the web platform and about its pedagogical value. The latter sub-belief, which had been neutral, seemed to quickly become positive, while the former remained positive. As Student 4 shared, “The operation of the web [platform] is convenient, as usual, but I have gradually been able to more clearly see the pedagogical value of the web platform” (RE). Student 11 reported, “The more I use it, the more I see how useful the web platform can be as a learning aid” (IE). This positive increase in the students’ sub-belief regarding the pedagogical value of the web platform seemed related to the positive experiences they had accumulated on the platform, although students’ practices were quite different in terms of their progress made on the platform. For example, Student 7 pointed out, “On the platform, I can see how others are thinking about the texts in different ways from me. Although I am not doing as well as them, I am learning from them and also presenting my contribution on the web in a very convenient way, without having to interact with them in person” (RE). Student 8 echoed, “I could see how other students shared their thoughts on the platform in a way that was more informative than in regular classrooms or conversations; their idea was quickly expressed orally and not easy for me to understand” (IE). Further, students who believed they did well also felt buttressed by the pedagogical role of the web platform, projecting their positive beliefs accordingly. They were benefiting from a motivating or positive vibe created by the web. As Student 20 indicated, “I know my comments will remain active for a long time. My classmates are reading my comments very carefully and are also reacting [to them]. I feel that learning is interactive and a bit more interesting when no assistance is used” (IE). While they gave more insightful comments than those shared by their peers during the learning, these students felt an increasing surge of interest in learning due to the way in which the platform made their contributions open and lasting. As Student 9 stated, “In class or before class, I often shared the ideas I nurtured during my pre-class reading, which were very innovative, but such ideas may be soon forgotten by my peers. With the web platform, I feel more motivated to share my thoughts on a reading text with my peers through the platform” (IE). Clearly, the students’ sub-belief about the pedagogical value of the web platform became increasingly positive, moderated by their prolonged use of the platform.

Against this context, understandably, the students’ beliefs about using the web platform in general at this point (which had been neutral in general) also manifest as positive. As Student 5 noted, “Overall, I felt more positive about the web-based learning … [and] more interested and willing to do activities on the platform” (IE). However, there were no clues regarding any potential interactions between the sub-beliefs, since they were both positive.

Within their beliefs about reading activities, the sub-belief about what they should master in terms of reading literacy (which had been neutral) remained the same. Student 6 remarked, “I still keep in mind the importance of becoming a critical reader” (IE). By contrast, the students’ sub-belief about what they could handle in relation to reading activities (which had been negative) began changing in a positive direction, although they were still tinged with negativity to different degrees among the student groups (i.e., based on how much difficulty they encountered). Student 9, who learned at a good pace, shared, “I still feel challenged by the demands of reading literacy. The challenges, however, are not as difficult as before” (RE). Student 7, who did not learn as fast as Student 9, affirmed, “I still could not get it as well as others. I do not know how to do well … and I feel like I am still comprehending only the surface meaning of the text. However, I feel I am on the way and making trickling progress through more practices” (IE). Notably, the students demonstrated changing beliefs with somewhat mitigated negativity, along with their increased practice of reading literacy in this context. They felt that they were able to handle most of the reading activities on the web platform. This was different from the earlier phase, in which they all held negative beliefs about what they could handle due to their lack of experience and familiarity with the pre-class task, which required them to be critical and discuss the deep meaning of the text.

In this scenario, the students’ beliefs about reading activities were generally a mixture of negative and positive beliefs (which, in general, had been negative), but positivity was slightly dominant. However, the positivity was not sufficiently strong to offset the negativity. As Student 13 indicated, “At this stage, I feel that I am more cheerful about the reading activities on the web, but this does not mean that I do not experience challenges at all. Obviously, I still do” (RE). The dominance of positivity also suggested a weak interaction between the two sub-beliefs (what they should master in terms of reading literacy and what they could handle in relation to reading activities).

More importantly, it also seemed that the students’ beliefs about reading activities were also demonstrated as malleable constructs interacting with their beliefs about using the web platform. In particular, their beliefs about what they could do with reading activities were like a bubble that crept upon them, instilled by their positive beliefs about using the web platform. As Student 3 pointed out, “While I still find reading literacy challenging, my reading ability is changing, as I receive help on the platform from my excellent peers” (IE). Student 4 added, “Especially in the context of the web platform, I feel I am being further encouraged by the ambiance created by the platform, and I really want to continue with this way of learning” (RE). For the fast-paced students, their beliefs about reading activities were additionally mediated by their expectations of learning more from their peers on the web. Student 9 stated, “Now I am offering and helping, but I know that I will also benefit beyond the motivating atmosphere I am exposed to on the platform” (IE). The students’ positive beliefs about their use of the web platform started to gently moderate their beliefs about reading activities, increasing the positivity of their beliefs about what they could do with reading activities.

Possibly due to the augmented positivity of the students’ sub-beliefs about what they could do with their reading, their beliefs about reading activities also seemed to proceed in the direction of positively embracing reading activities. As Student 3 remarked, “I need to keep going, practicing, and learning from others and do better on the reading task” (RE).

At this stage, the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning (which had been negative) were positive through the interaction of their positive beliefs about using the web platform with their slightly negative beliefs about reading activities. As Student 4 revealed, “I feel that my overall impression of the platform or the learning activities is far better now, driving my learning” (RE). Furthermore, Student 10 declared, “My learning is now motivated by my new conceptualization of the platform and reading activities and the positive influence of the former on the latter” (RE). The students’ beliefs about WBL were positively reconstructed through the interaction between the newly formed beliefs about using web platforms and their beliefs about reading activities.

The students’ positive beliefs about WBL were also reflected in their practices. Regarding platform use, there was more mutual assistance between the students at this stage than early on, illustrating the students’ augmented positive beliefs about using the platform for learning. According to the field notes, Student 8, for example, posed a question about an author’s supporting evidence being too personal and lacking in statistics or other types of proof. This was echoed by several other students (e.g., Students 5 and 7), who noted this and indicated the same concern (field notes). Although these students did not give any answers, the attention they gave to their peer’s questions showed their active use of the platform for learning (field notes). Some other students (e.g., Students 9 and 20), especially the fast-paced ones, also volunteered to answer their peers’ questions, regardless of the accuracy of their answers (field notes).

Regarding the reading activities, the students also seemed to act on their new beliefs (which were positive) and demonstrate their efforts beyond the surface meaning of the texts. For example, they critically engaged with new texts on the platform on their own, which could be seen in their inquiry into the logic of the paragraphs and their critique of the arguments presented in the text (field notes). A few students did not make substantial processes in this regard (e.g., Students 2, 8, and 13). While acknowledging the gap between them and others, the students began to actively digest the diverse perspectives shared by students on the web, refer to their peers’ work, and support their learning processes. For example, Student 9 posed a question about the logical connection between the two examples listed in two separate paragraphs. Student 8 then remarked, “When reading her [Student 9’s] questions, I thought that such inquiries could be applied to other paragraphs, so I posed a similar question” (RE). Due to the functionality of the platform, Student 8 was inspired by Student 9, which also suggests that Student 8’s engagement in the reading activity was enhanced in comparison with her earlier experiences.

The third phase: Dynamic factors, mitigation and restoration of the students’ positive beliefs, and their changing practices

Following the interactions in which the students’ beliefs about using the web platform triggered a positive change in their beliefs about reading activities, the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were mitigated in positivity. The mitigation of the beliefs, manifested through their beliefs about using the web platform and their beliefs about reading activities, did not occur at the same time; rather, the beliefs took turns and offset the other’s mitigation over time. The mitigation of the beliefs also demonstrated their respective features.

For the students’ positive beliefs about using the web platform, there was temporary recurrent mitigation regarding their sub-belief about the operation of the platform. The mitigation related to technological issues—namely, the irregular breakdown of the Internet or the platform itself—and the mitigation of the sub-belief occurred among all the students. As Student 12 pointed out, “Sometimes, you find your Internet does not work or the whole web freezes for a while” (RE). Student 11 added, “And then you feel so frustrated and a bit anxious” (RE). However, such mitigation of their positive beliefs was easy to recover, although it happened irregularly. As Student 7 stated, “Once the Internet recovered, my discomfort was gone” (IE). Student 8 revealed, “Sometimes I just worry that the platform will all of a sudden go wrong again” (IE). Overall, the mitigation of this sub-belief was temporary and recurrent, yet recoverable, during the students’ learning.

The students’ sub-belief about the pedagogical value of the web platform also demonstrated the mitigation but in a chronic way, and this issue was reported especially by the students who were learning at a slow pace. Student 8 stated, “I feel I was under pressure when I cannot effectively address the questions or reading activities while others are gradually doing well” (RE). Student 2 expressed, “It was nice to use the web platform to learn from others. I initially admired how my classmates were progressing quickly and excellently on the web, but over time, I’ve come to feel that I am really slow. I felt a kind of pressure in learning” (IE). Indeed, for each new text, most students improved over time, but a small portion did not make significant progress for a long time (field notes). By being exposed to the atmosphere for a long time, these students gradually started feeling uncomfortable with the platform and experiencing peer pressure, which overpowered their admiration for others and weakened their positive beliefs about the pedagogical affordance of the platform. Recall that in the early stage, the students’ beliefs about the pedagogical value of the platform were positively activated in relation to their continued practices. The mitigation that occurred at this time seemed to suggest that their positive beliefs, which emerged from their beneficial experiences of peer learning and their expectations of their future progress, were diluted by their disappointment with their ongoing experiences with the platform. Namely, the mitigation occurred in relation to clashing factors, including what they were experiencing, what they had experienced, and what they expected of their practice.

All the students experienced a mitigation of their beliefs about reading or, more precisely, of their sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities. The other sub-belief about what they should do as student readers remained unchanged. As Student 5 stated, “I know what I should do as a student reader, but reading activities have been difficult for me … at least sometimes” (IE).

Different student groups also experienced the extent of the belief mitigation differently. Recall that the students’ sub-belief about what they could do with reading literacy was positively activated by moderating factors, for example, the affordances of technology use on different dimensions (i.e., further motivating fast-paced students and activating slow-paced students to learn from others). However, at this time, the slow-paced students, for example, Student 5, further shared, “It is not improving. It makes me feel disappointed and bad now” (RE). These students felt that they had not made as much progress with their reading-related learning as they had expected; as such, the positive sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities that had resulted from their early momentum was mitigated.

However, for fast-paced students, their positive sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities was mitigated in an unsystematic way, as shown by inconsistent mitigation over time. This unsystematic mitigation was particularly related to the unique difficulty of the new text. As Student 11 revealed, “Sometimes a new task is so difficult to comprehend … and I do not know how to critically deconstruct the text” (IE). Student 12 echoed, “I know the method for doing the deep reading, but things, such as unfamiliar topics, bother me, and I feel no breakthrough. Once I suddenly feel like I might not be doing well, I feel frustrated about the reading activity” (IE). Indeed, these students had been working hard toward reading and held positive beliefs based on their performance. Their sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities fluctuated into a negative zone because of their experiences with unfamiliar topics that occurred irregularly in the textbook, outside the scope of their knowledge domain. That is, this fluctuation occurred, probably due to factors such as their lack of experience navigating the complexity of a learning journey (i.e., the difficulty of reading may not always fit in with their knowledge repertoires) or their high self-esteem as fast-paced students.

Against this background, however, it was observed that there was rudimentary mutual support between the two domains of their beliefs in relation to web-based collaborative learning. When one turned negative, it was bolstered by the other, although the aforementioned mitigation did not occur at the same time; rather, it occurred in different phases.

However, as mentioned early on, all the students experienced mitigation in their beliefs about the web platform, especially in terms of the sub-belief about their operation of the platform. This mitigation was soon offset by their previous and ongoing beliefs about reading literacy, especially their sub-belief about what they should do as student readers. For example, Student 14 said, “So far, this venue is the best one for improving my reading and meeting the demands of the reading. Improving my reading is my top priority, so I can overcome it” (RE). Student 7 acknowledged, “Developing reading literacy is my priority. I also feel that I was learning from my classmates and becoming motivated in my learning, so the technological issue is not a big deal” (IE). Thus, the students’ sub-belief about the importance of reading literacy development or what they should do as student readers made them feel that the Internet issue should be overcome, re-activating their mitigated beliefs about using the web platform.

In particular, among students whose positive sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities was mitigated when they could not see their progress on the web platform, Student 2 said, “I know the importance and usefulness of developing critical literacy on the web, although I still feel I could not make much more progress” (IE). For slow-paced students, their mitigated sub-belief about what they could do as student readers were re-activated by their positive sub-belief in the pedagogical value of the web platform, although in a weak manner. Recall that fast-paced students’ positive beliefs about reading literacy were mitigated due to their lack of experience navigating the learning process and the irregularity of texts. Such mitigated beliefs were passively buttressed by the need to engage in web-based collaborative learning. Student 11 declared, “I felt confused and challenged … or even a bit crazy about reading literacy … But I know that no matter what, I have to finish relevant activities … and share with my classmates … I do not want to look so bad” (IE). The students’ mitigated sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities was passively restored, but not fully restored, by their need to engage publicly in WBL activities. Overall, the mitigated beliefs related to students’ WBL were mutually bolstered at times, featuring weak or passive recovery.

When the beliefs had not bolstered each other (due to the time needed), the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were both positive and negative, with their negative sub-belief being dominant. As Student 6 stated, “While harboring a partially positive attitude toward web-based collaborative learning, either my negative stance toward the platform or reading practices constrained my practices” (IE). Regarding their newly emerged negative sub-belief about the operation of the web platform, it could be observed that several students altered the layout of their discussions, not only in terms of font but also in terms of the order of the questions. As Student 4 pointed out, “During my use of the web platform, I experienced a period in which it was difficult to do activities regularly on the web due to periodic Internet issues, so I did not treat it as seriously as I did previously” (RE). Students’ negative sub-belief about the operation of the platform were transferred externally and reified by their “messy” use of the web platform.

Similarly, in terms of the emergence of their negative sub-belief about what they could do with reading activities, the two groups of students also demonstrated corresponding practices. The field notes show that slow-paced students demonstrated a relapse into focusing on superficial meaning at the level of a whole text or paragraph. As Student 6 revealed, “Given my negative emotions during the learning, I felt no motivation to behave well” (RE). Meanwhile, fast-paced students’ practices alternated between good ones and undesirable ones. Student 2 acknowledged, “My performance is the actual barometer of my stances toward my reading activities … You know, the text is inconsistent in terms of difficulty” (IE).

However, as the students’ beliefs about web platforms and reading activities bolstered each other over time, the overall result was that the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were positive, although in a mitigated way. As Student 8 shared, “My stances toward the learning activities are mixed, with both positive and negative ones, but I feel that I have, on the whole, resumed my investment in the learning” (RE). The students acted upon the positive dimension of the two beliefs, as exemplified by their reactivated engagement with their learning (field notes). The negative dimensions seemed to be offset, muffled, and no longer reflected in their web-based collaborative learning.

It seemed that, at this point, the students’ practices were not fully conditioned by their beliefs, especially given the existence of a negative aspect in their beliefs about reading. Instead, their web-based collaborative learning seemed also additionally related to the academic context in which, at a specific time of the semester, they had to galvanize themselves in giving their best efforts. As Student 5 stated, “But now we are almost halfway through the semester. As a student at this university, I have to work hard in class. And working hard is also related to my GPA and my future” (IE).

The Fourth phase: Stabilized coexistence of students’ beliefs about WBL, moderating factors, and their practices

Students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning gradually became stable in conjunction, as manifested by the increasing stability of the positivity in their beliefs about using web platforms and their beliefs about reading activities. As Student 1 pointed out, “After extended engagement, my conceptualization of the platform and reading activities we are exposed to is now mature … as is my conceptualization of the learning on the whole” (IE). Student 2 shared, “My accumulated experiences with the platform and the reading have brought me to this level” (IE). The stability of the students’ beliefs was made possible, along with the moderation of the students’ prolonged experiences with web-based collaborative learning.

However, their beliefs were not stabilized in a simplistic way. Instead, the stability was characterized by a stable mixture of sub-belief constructs pertaining to their beliefs about using web platforms and their beliefs about reading activities. In each domain of beliefs, the positive sub-belief construct was stably dominant. In terms of their use of the web platform, the beliefs the students stably held still comprised negative sub-beliefs, either about the Internet issue (the operation of the platform) or, to some extent, their awareness of how the platform brought their slow progress to their attention (the pedagogical value of the platform). For instance, Student 4 acknowledged in the latter half of the semester, “For me, the technological function of the platform is not perfect … but I feel I have become used to the constraints related to it… Now, the glitch is nothing to me in comparison to the value of the platform as an easy-to-operate tool and the pedagogical benefits I get” (IE). Further, recall that Student 5, a somewhat slow-paced student, had worried about her slow performance in comparison with others on the web platform, an exposing and public space. Student 5 now reported, “I think I have become used to this while being aware that my progress on the web platform is not as fast as others … I now consider the platform a place of learning and give priority to the progress I have made, not my progress in comparison to others” (IE). Moderated by sufficient engagement with the web platform, the students’ positive beliefs about the platform’s technological operation or pedagogical role were sufficiently strong to consistently muffle—but not eliminate—the power of their negative beliefs about the platform’s function or pedagogical role. Overall, the students demonstrated positive beliefs about using web platforms, which remained consistent in the latter stage of their use of the platform.

A similar configuration of beliefs was found in the students’ beliefs about their reading activities. That is, there was no longer a dynamic interaction among its sub-beliefs; rather, there was a stable coexistence, with the students’ positive sub-beliefs consistently dominating their negative beliefs. Student 14, for example, stated, “I have a mature understanding of the demands of literacy; I have come to acknowledge its importance over time. However, due to my limited knowledge, I still feel a bit challenged in meeting the demands fully” (RE). Student 17 added, “I feel that I now fully understand the demand, which is to expand our horizon and way of thinking based on our experiences. I must admit that I still may sometimes not meet the demands, but I try willingly and do my best” (IE). Moderated by prolonged engagement in the reading tasks on the web platform, the students began to exude a dominant and stable positive sub-belief about the reading demands; at the same time, a negative sub-belief about the reading demands was also observed, which was also consistently coexistent but weak and dominated by their positive belief.

Similarly, regarding the students’ beliefs about reading activities, they felt that they could consistently do well in uncovering the core dimensions of the deep meaning of a text. As Student 6 pointed out, “Over time and with practice, I feel I have become familiar with the key components related to the deep meaning of a text, such as the authoritativeness of evidence [and] the logic between the paragraphs” (IE). However, they also harbored uncertainty or negative beliefs formed from their practices, namely, the mismatch between what they needed to do and what their knowledge allowed them to navigate (for example, the topic of a new text). The students’ negative sub-beliefs also consistently coexisted with and were dominated by their positive sub-beliefs. Student 11 claimed, “Based on what I have seen, my progress was not necessarily incremental, but I now feel comfortable with the challenges and the reading activities” (IE). Student 9, who did somewhat better than the others, even during the early phase of the semester, acknowledged, “When it comes to a new text, I occasionally still feel a bit uncertain about my ability, but I know that I am making progress and am used to these reading activities” (RE). Overall, regarding the students’ sub-beliefs about reading demands or about reading activities, the students predominantly demonstrated positive belief constructs, which consistently coexisted with, but did not eliminate, their negative belief constructs about reading. As such, the students in the latter stage of their reading activities demonstrated their beliefs positively and consistently.

The trend of stability within and across the students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning seemed to occur along with the maturation of their conceptualization of the hampering/negative factors formed in their WBL practice and buttressed the stability of their aforementioned beliefs about WBL. As Student 11 stated, “Learning new skills is about adjustment and re-adjustment. Challenges in the process are not excuses for us to give up” (RE). Student 2 also agreed, noting, “To be advanced learners, we must overcome difficulties across all dimensions … [There is] no need to care about self-esteem or how challenging knowledge digestion is” (IE). The students formed another belief in their practice, one concerned with their stance toward factors that hampered their learning. This additional new belief did not occur suddenly; it was derived from the positive beliefs that predominantly existed in their beliefs about web-based collaborative learning and expanded and matured over time during the students’ practice. Their beliefs about learning challenges muffled and froze their negative beliefs about using web platforms and their negative beliefs about reading literacy, which, in turn, consistently coexisted with their positive beliefs. Student 12 reported, “Once you know how to overcome the challenges of advanced learning, you will know how to practice WBL and continue with your learning” (IE). The students’ newly formed beliefs about the negative side of the learning process seemed to be a factor, acting as a pedestal on which students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning were consistently rested, and guided the students’ practice.

Beyond each domain of the students’ beliefs, stability was also observed between the beliefs of the two main domains, which seemed to consistently coexist with each other. That is, without any further dynamic interaction, the domains each branched out stably and positively, simultaneously supporting the students’ WBL. As Student 12 revealed, “These beliefs are now co-working within me simultaneously to promote my learning” (RE). Student 3 stated, “I feel that I am being pushed forward by the two streams of conceptualization at the same time, and they are not taking turns like before” (IE). The beliefs that played out were the positive beliefs from the two main belief domains, which each augmented the power of the other. This pattern was different from what was seen in the early phase, where positive beliefs about using web platforms and reading literacy took turns helping the other regain positivity.

Further, in the early phase, the role of students’ positive beliefs about the web platform was clear, which buttressed the development of their beliefs about what they could do with reading activities. This was understandable since what they could do with their reading literacy was a long and complex process, immune to the support available. As Student 8 remarked, “It took time to become good enough to practice reading literacy, which is new and challenging” (RE). By contrast, in the latter half of the semester, coexistence between the two main beliefs was observed. This was mostly because the students’ beliefs about reading activities evolved into stabilized ones, which were predominantly positive and immune to the dynamic influence of the other beliefs. For example, Student 12 pointed out, “I know how these practices help develop our reading literacy, and I do not get lost like before. And I do not need or look for any mental support” (IE).

Notably, the negative branch of the students’ beliefs about using web platforms and their beliefs about reading activities seemed to remain inert at this point. Student 3 stated, “In my mind, there is still a negative side to the web platform … and reading literacy. However, they are inert within and beyond, although still existent, just like what I experienced at the beginning of the semester” (RE). In other words, negative beliefs still existed, but due to their inertness, they did not play out across the domains of the students’ beliefs. This was similar to the previous stage of the semester, in which the students’ negative beliefs did not extend themselves to affect other negative or positive beliefs across or within the two domains of beliefs about web-based collaborative learning. What was different about these beliefs compared to the students’ negative beliefs from early on was that the new negative belief consistently existed, without mitigation or recovery. This difference may be due to newly emerging beliefs, as mentioned earlier in this section. As Student 9 pointed out, “We are not at the beginning anymore; we know what is going on with learning … [and] challenges or constraints are inevitable” (IE). In other words, along with the students’ newly emerging beliefs and prolonged practices, their negative beliefs were mitigated to an appropriate extent, leading to the stable coexistence of their negative beliefs with their positive beliefs.

With such a stabilized state among and within their beliefs about web-based collaborative learning (i.e., being stably positive in general), the students’ practices also entered a regular phase. As Student 17 mentioned, “I am just regularly doing the task, just the same as how I feel about reading and the technology” (RE).

In terms of the students’ use of the platform, the order of their activities was continuously maintained, not only in terms of format but also in terms of their timeliness (field notes). This was different from the early half of the semester, although the Internet issue still existed.” Student 4 pointed out, “Practicing on the platform is natural for me; Internet problems are negligible for me. And I also do not care about, nor do I feel the existence of or the necessity of caring about, peer pressure” (IE).

Similarly, in terms of reading activities, the students’ practices were also stable, corresponding to their beliefs. The students regularly and diligently posted and answered questions as expected by the course (field notes). Even those who had low confidence (e.g., Students 5 and 7) were actively engaged in the activities, presenting their questions and answers in a deep way (field notes). Consistent engagement was particularly observed through their regular participation in the discussions surrounding concerns raised by other students and in their in-class discussions with the instructor (field notes).

The students also tried their best to post and answer their classmates’ questions in the later part of the semester (field notes). For example, the slow-paced students constantly used what they had learned from the web and posted new questions (field notes). The fast-paced students also consistently posted questions by synthesizing their own knowledge and what they had learned (field notes). Mediated by the students’ newly emerging beliefs about study challenges, the students also demonstrated corresponding practices, which included their regular and timely posting of questions and their contributions to answers, albeit challenges they faced (field notes). As Student 7 stated, “Even in the latter half of the semester, I still found some texts to be particularly difficult. But that did not hurt my practices and engagement.” Student 9 indicated, “I try my best and see challenges as a natural part of my practice (IE).”

Discussion and implications of the study

In response to the research question investigating what EFL student readers’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning look like over time, the study reveals that the positivity of students’ beliefs and sub-beliefs about web-based collaborative learning changed over time. On the one hand, the existence of main beliefs and sub-beliefs corroborates previous findings on students’ WBL and furthers our understanding of the multiple layers of students’ beliefs, including in the EFL context (e.g., Alhamami, 2019) and the field of general education (e.g., Green, 1971).

While factors emerging from student readers’ learning were also responsible for the changing positivity of their beliefs about web-based collaborative learning (see also the answers to research question 2), the current study uniquely reveals that the dynamic positivity was also related to the interactive pattern between the students’ two main beliefs about web-based collaborative learning (i.e., beliefs about using web platforms and about reading activities), including the interactions between the sub-beliefs of the two main beliefs. For example, an interaction was found between the students’ two main beliefs about web-based collaborative learning that mutually enhanced the positivity of both beliefs. There were also dynamic interactions between the sub-beliefs about web platform use and reading activities, including a transition from no interaction through slight interaction to taking turns to restore each other’s positivity.

The findings about the dynamic evolution of student readers’ beliefs and the relation of their sub-beliefs to their mutual interaction are new, especially in the field of WBL in the context of EFL students. Indeed, in the WBL context, research seems to have generally adopted a quantitative approach, focusing on the correlation between different dimensions of beliefs (e.g., Aslan and Thompson, 2021; Koraneekij and Khlaisang, 2019; Lee and Lee, 2014) and thus providing a somewhat static view of this relationship. Further, studies using a qualitative approach to demystify students’ beliefs in the field of WBL (e.g., Ahmed, 2022; Alhamami, 2019; Han, 2017; Zhu and Wang, 2019) did not yield an appropriately detailed understanding of the evolution or interactive dynamics of the multiple layers of students’ beliefs in relation to their WBL. This shortcoming may be due to time constraints associated with the observation of the dynamics of students’ beliefs and sub-beliefs or to the researchers’ lack of interest in teasing apart students’ beliefs for more nuanced scrutiny over time (e.g., a semester). As such, the current study innovatively sheds light on the changing positivity of students’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning in relation to the dynamic interactions of students’ WBL-related beliefs (and sub-beliefs) over time.

In response to the second research question, which addresses the factors moderating student readers’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning, the study shows that such beliefs were constructed and re-constructed in relation to diverse factors that emerged over time (i.e., their previous and ongoing experiences with web-based collaborative learning, such as their adjustment to using the web platform). Very little mention has been made of this finding in the field of WBL, but it echoes studies in the field of EFL (e.g., Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011; Han, 2017) that have reported the dynamic construction and variation of students’ beliefs. If the study had been conducted through a qualitative approach in tandem with short-term data collection or limited data sources or if it had used a quantitative method, the diversity in the factors influencing web-based collaborative learning might not have been revealed (see also the discussion of research question 1). In contrast, the qualitative approach taken in the current study involved collecting multiple sources of data over one semester and was sensitive to the dynamic factors pertaining to the students’ web-based collaborative learning.

Regarding the third research question, which addressed the relationship between student readers’ beliefs and practices during web-based collaborative learning, the study demonstrates that the students’ beliefs either drove or constrained their practices. The positivity of students’ beliefs (including their sub-beliefs) about web-based collaborative learning changed during the process of their WBL practices. In general, their beliefs were positively correlated with their use of web platforms or practice of reading activities. This finding resonates with previous studies on students’ beliefs, in both the fields of EFL (Han, 2017) and WBL (e.g., Lobos et al. 2021), which reported the construction and development of students’ beliefs. In this sense, through its qualitative approach, this study complements largely quantitative studies (e.g., Koraneekij and Khlaisang, 2019) on the configuration of students’ beliefs about WBL. It also offers qualitative evidence of the close relationship between students’ beliefs and their practices, especially in a university WBL-based EFL reading context.

However, the current study found a mismatch between the student readers’ beliefs about web-based collaborative learning and their practices. For example, despite their positive beliefs about reading activities (one domain of beliefs about the learning), the EFL students did not practice to the best of their ability, an outcome related to the emergence of internal or external constraints pertaining to their learning context (e.g., how well they could navigate the complexity of a task). Similarly, although the students temporarily had negative beliefs about the learning, they practiced it devotedly because of the intervention of factors pertaining to their learning context (e.g., awareness of who they were and where they were in the learning context or another positive belief related to WBL). Alternatively, their negative beliefs were mediated by the new beliefs (e.g., about learning challenges) that emerged during their learning. This mismatch between beliefs and practices is in line with the findings of studies conducted beyond the field of WBL, such as in language education (Han, 2017; Barcelos and Kalaja, 2011), suggesting that the positive correlation between students’ beliefs and practices may be vulnerable to interfering factors at the internal or external levels. The observed mismatch, however, has been scarcely addressed in previous studies on WBL (e.g., Koraneekij and Khlaisang, 2019). In this sense, the finding enhances our understanding of the relationship between students’ beliefs and practices in the context of WBL.

As noted in previous sections, this finding in relation to research question 3 was also made possible primarily due to the sustained qualitative tracking of students’ learning over a semester in tandem with the use of multiple data sources. Thus, the current qualitative study adds to the understanding of the dynamic relationship between students’ beliefs and practices pertaining to web-based collaborative learning, especially in an EFL context and bridges the gap left by previous studies having largely used quantitative methods or tracked students only for short periods (e.g., Ahmed, 2022; Lee and Lee, 2014).