Abstract

The aim of the present study was to explore the structural relationships between self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being among Chinese (N = 3595) and Canadian (N = 2056) adolescents. A structural equation modeling (SEM) approach was adopted by means of a multi-group analysis. Within the aggregate sample, empathy and interpersonal trust were shown to be related to mental well-being both directly and indirectly, with friendship quality as the mediating variable, whereas self-control merely had a direct effect on mental well-being. The multiple-group analysis revealed a series of discrepancies, showing that empathy had a significant impact on the mental well-being of Chinese but not Canadian adolescents. Furthermore, empathy exerted a significantly stronger effect on friendship quality for Chinese than for Canadian adolescents, whereas interpersonal trust had a significantly stronger impact on friendship quality among Canadian than among Chinese adolescents. The differences were discussed from a cross-cultural perspective concerning collectivism versus individualism. The measures employed in the present study are closely related to social and emotional skills; the findings therefore may point to benefits for both Chinese and Canadian adolescents in terms of enhancement of their cultural-specific social and emotional skills as well as their well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the burgeoning discipline of positive psychology, scholars are increasingly interested in exploring mental well-being (Boals et al. 2011; Gokalp 2023; Jakovljevic 2018; Ryan and Deci 2001). Mental well-being refers to a dynamic state of positive emotional and psychological functioning (Ryan and Deci 2001), which comprises individuals’ capabilities to develop their potential, perform productively and creatively, build favorable interpersonal relationships, and contribute to their communities (Kirkwood et al. 2008). Mental well-being has been shown to be beneficial for physical health, psychological resilience, supportive relationships, and social interactions (Diener et al. 2018; Kirkwood et al. 2008; Miething et al. 2017) and is therefore highly significant for individuals.

Much research has revealed that individuals’ mental well-being is closely relevant to their interpersonal relationships (Clarke et al. 2021; Wei et al. 2011; Zaki 2020). Furthermore, self-control, empathy, and interpersonal trust, which are crucial factors underlying interpersonal relationships, have been proven to be strong contributors to mental well-being (e.g., Betts and Rotenberg 2007; Gokalp 2023; Hecht et al. 2022; Kim et al. 2012); and friendship quality has also been shown to be the predominant interpersonal-related element of those factors that positively affect psychological experience and mental well-being (Chen et al. 2004; van der Horst and Coffé 2011; Zhou et al. 2020). Research on the associations among adolescents’ social and emotional skills, interpersonal relationships, and well-being has been prevalent in recent years (Collie 2022; Durlak et al. 2011; Miyamoto et al. 2015). However, the effects of three fundamental social and emotional skills, that is, self-control, empathy, and trust, on interpersonal relationships (e.g., friendship quality) and well-being have rarely been discussed among Chinese and Canadian adolescents (OECD 2019, 2021).

Critically, the above-mentioned social-emotional-related variables have culturally specific meanings. Trust is prone to be strongly promoted by individualism as in Canada (Guo et al. 2022; van Hoorn 2015), whereas empathy and self-control are considered to be more predominant for collectivism as in China (Heinke and Louis 2009; Seeley and Gardner 2003). As opposed to individualist people who emphasize the personal side of friendships, collectivist people view friendship as a means for integration into the wider societal system (Gummerum and Keller 2008). Also, researchers have shown that self- and interpersonal-related factors exert distinct influences on well-being according to individualist versus collectivist context (Guo et al. 2022; Jasielska et al. 2018; Park and Huebner 2005). Thus, in consideration of such underlying cultural differences, a cross-national comparative study designed to improve social-emotional educational practices and mental well-being for Chinese and Canadian adolescents would appear to be very worthwhile.

Literature review

Self-control and mental well-being

As the core component of self-regulation, self-control involves a series of goal-directed competencies that are said to regulate personal thoughts, attitudes, emotions, and behaviors (Carver and Scheier 1981; de Ridder et al. 2012). Self-control reflects individuals’ propensity to facilitate goal realization and conquer goal-disruptive desires (de Ridder and Gillebaart 2017). Numerous studies have confirmed the positive relationship between self-control and mental well-being (e.g., Boals et al. 2011; Converse et al. 2018; Gokalp 2023; Hofmann et al. 2014; Kim et al. 2022). More importantly, researchers have identified how the mechanism operates. Emphasizing the key role of purposeful manners, Hofmann et al. (2014) demonstrated that individuals with higher self-control are less likely to experience conflicting goals in various life domains. Similarly, de Ridder and Gillebaart (2017) found that self-control contributes to people’s well-being by activating adaptive behaviors (e.g., goal-directed means) and impeding maladaptive behaviors (e.g., goal-disruptive temptations). Furthermore, research suggests not only that self-control is positively correlated with mental health and psychological resilience (Gokalp 2023) but also that individuals who have low self-control have low mental well-being (Kim et al. 2022) because they are more likely to adopt unhealthy coping strategies (e.g., avoidance coping) which may lead to low levels of mental health (Boals et al. 2011).

The extant large body of research has primarily examined the effect of self-control on adolescents’ mental well-being regarding the overcoming of undesirable problems, with self-control as a mediator or moderator. These problems have included excessive internet use, electronic game disorder, academic alienation, parent-child conflict, tolerance deviance, sleep quality, and emotional dysregulation, as well as other internalizing and externalizing symptomatology (e.g., Li et al. 2021; Wills et al. 2016). Fewer studies concerning positive functioning (e.g., friendship quality) have shown a connection between self-control as the potential predictor and the mental well-being of adolescents. Developmental changes regarding the association between self-control and mental well-being occur during adolescence (Kim et al. 2022). More than that, a longitudinal study conducted by Converse et al. (2018) indicated that various positive outcomes linked to self-control during adolescence may underlie ensuing success and longer-term well-being in young adulthood.

Empathy and mental well-being

Empathy is viewed as the capacity to take another’s perspective and experience the consequent thoughts and emotions (Davis,1996; Stewart et al. 2015). The relationship between empathy and personal mental well-being is increasingly a key focus of research (Hecht et al. 2022; Jakovljevic 2018; Wei et al. 2011; Zaki 2020). Jakovljevic’s (2018) research suggests that empathy, such as in the demonstration of love, kindness, and compassion in interpersonal communications, enhances individuals’ confidence and sense of coherence, thereby causing greater resilience and mental well-being. Wei et al. (2011) argued that empathic individuals generally have higher well-being levels: When people show empathy towards other people, the latter are more likely to feel grateful and act kindly in response. Such a friendly and supportive connection heightens the happiness, life satisfaction, and positive emotions of empathizers (Huang et al. 2018; Wei et al. 2011). Furthermore, it has been found that empathy can alleviate individuals’ mental ill-being, for example, their depressive symptoms (Schreiter et al. 2013).

Zaki (2020) demonstrated how empathy heightens peoples’ mental well-being through emotion regulation which concerns a goal-related process and which occurs when individuals appraise a shared emotional state. It has been found that through social interactions, people regulate their own emotions and also affect others’ emotions, and that reciprocal empathic concern reflects individuals’ successful social relationships and mental well-being (Stewart et al. 2015; Zaki 2020). With an emphasis on the destigmatizing effects of empathy, the findings by Hecht et al. (2022) revealed that empathy and reflectiveness are protective factors in the reduction of individuals’ mental health stigmas, thereby enhancing mental well-being. Specifically, empathic accuracy, that is, the extent to which people can reckon others’ inferences and preferences, exerts a stronger influence than reflectiveness on relationship satisfaction (Sened et al. 2017). Accurately perceiving and assessing the emotional states of peers may be beneficial for individuals’ life satisfaction, close interpersonal relationships, and even a functioning society (Huang and Su 2014; Sened et al. 2017; Wei et al. 2011).

Interpersonal trust and mental well-being

According to Rotter (1967), interpersonal trust concerns an expectancy held by an individual that the promise or statement of another individual can be relied on, and reflects individuals’ willingness to be vulnerable to others based on the assumption that these others will perform beneficial and favorable actions (Mayer et al. 1995). Interpersonal trust increases throughout life and makes for support, comfort, and pleasure from others, and is conducive to an extensive social circle, salutary health, and a high-quality life (Poulin and Haase 2015; van Hoorn 2015). Many studies confirm a positive relationship between interpersonal trust and mental well-being (e.g., Clarke et al. 2021; Helliwell and Wang 2011; Kim et al. 2012; Martinez et al. 2019; Miething et al. 2017). Martinez et al. (2019) noted that low interpersonal trust and high depression are indicative of personal distress, and Clarke et al. (2021) demonstrated in a review study that interpersonal trust tends to bring about an improved quality of reciprocal communications and also a decrease in the potential of mental illness. Using data from the Gallup World Poll and the Canadian General Social Survey, Helliwell and Wang (2011) revealed that reciprocal trust relationships, as vital components of social capital, can facilitate individual life evaluation and satisfaction. Furthermore, the bidirectional interdependence between friendship trust and psychological well-being was observed in the population of late adolescence to early adulthood by Miething et al. (2017).

Recently, scholars have explored underlying individual uniqueness in profiles of trust and well-being, using multidimensional and comprehensive cases of cross-cultural differences (Guo et al. 2022; Luo et al. 2023; Zhang 2020). For instance, employing 13,823 samples across 15 nations, Luo et al. (2023) revealed how greater similarities in national interpersonal trust profiles occur in countries that exhibit more similar tightness-looseness propensities in the prevailing social ethos. The authors also showed that, for loose rather than tight cultures, greater individual life satisfaction is predicted by a higher degree of similarity between individuals’ and society’s trust profiles (Luo et al. 2023). Likewise, Guo et al. (2022) pointed out that individualism may enhance the association between trust and well-being, and that interpersonal trust in collectivist societies probably derives from adherence to social norms rather than personal predilections. These findings support the view that mental well-being depends on subject preferences, particular values, and social beliefs, all of which are related to specific cultural contexts (Diener et al. 2018; Jasielska et al. 2018; Park and Huebner 2005; Zhang 2020).

Friendship quality as the potential mediator

Friendship is viewed as the symbol of high-quality interpersonal relatedness, with understanding, sharing, intimacy, loyalty, and authenticity as its core components (Chen et al. 2004; Gummerum and Keller 2008). Studies have revealed a positive correlation between friendship quality and mental well-being. For example, Zhou et al. (2020), employing the China Education Panel Survey (CEPS), argued that both cross-gender and cross-hukou-location friendships are positively associated with Chinese adolescents’ positive mental health and psychological well-being. Similarly, a Canadian case indicated that more personal contact and greater friendship heterogeneity bring about better social support and less psychological stress, and also ameliorative poor mental health states (van der Horst and Coffé 2011). Conversely, friendship conflicts may lead to depression, anxiety, and stress, all of which are detrimental to the global mental well-being and psychological experience of adolescents (Kong et al. 2022).

Theoretically and empirically, many internal and external factors are relevant to interdependent friendships (Akers et al. 1998; Betts and Rotenberg 2007; van den Bedem et al. 2019). Betts and Rotenberg (2007) confirmed that high self-control promotes peer trustworthiness, which in turn may be a facilitator for peer acceptance and improved school adjustment. Conversely, low self-control is more likely to induce friendship conflicts and reduce the quality of adolescent friendships (Boman et al. 2019). Adopting a criminological perspective, Boman et al. (2012) argued that low attachment, trustworthiness, and self-control may imbue friendships with coldness and brittleness. On the other hand, studies have demonstrated the positive effect of empathy on friendship quality (e.g., Ciarrochi et al. 2017; van den Bedem et al. 2019), and a longitudinal case has identified the bidirectional relationship between empathy and friendship quality in adolescence (van den Bedem et al. 2019). Therefore, according to the literature we have discussed, it may be proposed that friendship quality mediates the potential relationships between self-control and mental well-being, between empathy and mental well-being, and between interpersonal trust and mental well-being.

The present study

This study attempts to explore how self-control, empathy, and interpersonal trust influence adolescents’ mental well-being, with friendship quality as a potential mediator. Self-control, empathy, and interpersonal trust are three crucial elements of social and emotional skills (OECD 2021). The potential relationships among these variables have been infrequently examined in the contexts of China and Canada, which demonstrate the cultural values of collectivism and individualism, respectively (Chen et al. 2004; Rubin et al. 2006). Within educational discourse, although single-country samples have largely been used in extant studies that investigate social-emotional skills and well-being, cross-cultural research on these issues from the perspective of comparative education appears to be worthwhile. Potentially, such research would not only provide empirical evidence for various countries regarding enhancing their educational practices but would also achieve deeper global understandings, a fundamental for comparative education (Bray et al. 2014).

Based on existing evidence in the literature, four hypotheses were formulated as follows.

H1: Self-control (a), empathy (b), and interpersonal trust (c) are each positively associated with friendship quality.

H2: Friendship quality is positively associated with mental well-being.

H3: Self-control (a), empathy (b), and interpersonal trust (c) are each positively associated with mental well-being.

H4: Self-control (a), empathy (b), and interpersonal trust (c) are each positively associated with mental well-being via friendship quality.

The following hypotheses were formulated to verify whether China and Canada differ in terms of the potential relationships displayed in Fig. 1.

H5: The variable of the country will have some moderating effects on relationships between (a) self-control and friendship quality, (b) empathy and friendship quality, (c) interpersonal trust and friendship quality, (d) friendship quality and mental well-being, (e) self-control and mental well-being, (f) empathy and mental well-being, and (g) interpersonal trust and mental well-being.

Gender and socioeconomic status (SES) were incorporated as covariates in the current model. On the one hand, these variables have been widely used in this way to ensure the unbiasedness of results in social sciences research (Bernerth and Aguinis 2016). On the other hand, they are theoretically and empirically relevant to friendship quality and mental well-being according to previous studies (Akers et al. 1998; Ciarrochi et al. 2017; Lwasaki 2023; Oberle et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2020).

Methodology

Data sources

The data of the current study were obtained from the 2019 Survey on Social and Emotional Skills (SSES 2019), a large-scale project conducted by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). SSES 2019 involved more than 60,000 students from 10 cities across nine countries and explored potential characteristics and contextual factors regarding students’ social and emotional skills (OECD 2019). The survey assessed variables covering personal characteristics, psychological traits, emotional discrepancies, and interpersonal relationships (e.g., mental well-being, self-control, empathy, trust, as well as perceived relationships with friends), over two cohorts: 10-year-old (the younger cohort) and 15-year-old (the older cohort) students. The age range in the younger cohort was 10.7–10.9 years and in the older cohort, 15.6–16 years (OECD 2021). A two-stage stratified probability sampling design (sampling schools at the first stage and students at the second stage) was administered to gain a representative sample for each participating country (OECD 2021). The present study employed a cross-sectional design, using student questionnaires administered in Suzhou (China) and Ottawa (Canada). Specifically, the samples, both of which were taken from the 15-year-old cohort, contained 3595 students (boys, N = 1841; girls, N = 1754) from 76 schools in Suzhou, and 2056 students (boys, N = 1038; girls, N = 1018) from 62 schools in Ottawa. Informed consent for each of the participants in the study had been officially gained by the international organization OECD.

Measures

Self-control

Self-control (SEL) was comprised of six items in the student assessment final scales. However, one indicator with low item-to-construct loadings was eliminated in order to improve reliability as well as purify the measurement model (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Bollen 1989). The final scale incorporated five items: (a) Can control my actions, (b) Think carefully before doing something, (c) Avoid mistakes by working carefully, (d) Stop to think before acting, and (e) Often rush into action without thinking. All indicators were assessed with a Likert-type format with ratings from 1 to 5, respectively, as follows: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. Higher scores represented better self-control. Cronbach’s α = 0.76.

Empathy

Empathy (EMP) incorporated six items within the student assessment final scales, but two items with low item-to-construct loadings were eliminated in the current study (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Bollen 1989). The four indicators were (a) Can sense how others feel, (b) Know how to comfort others, (c) Understand what others want, and (d) Warm toward others. All indicators were assessed with a Likert-type format with ratings from 1 to 5, respectively, as follows: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. Higher scores indicated more empathy. Cronbach’s α = 0.70.

Interpersonal trust

Interpersonal trust (TRU) included six items within the student assessment final scales, but one item with low item-to-construct loadings was eliminated in the present study (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Bollen 1989). The final scale contained five items: (a) Believe that my friends can keep my secrets, (b) Distrust people, (c) Believe that other people will help me, (d) Believe that most people are honest, and (e) Trust others. All indicators were assessed with a Likert-type format with ratings from 1 to 5, respectively, as follows: “strongly disagree”, “disagree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “agree”, and “strongly agree”. Higher scores showed more interpersonal trust. Cronbach’s α = 0.83.

Friendship quality

Friendship quality (FRQ) was measured by perceived relationships with friends. Four items, as follows, indicated to what extent students perceived their friendship level: (a) My friends understand me, (b) My friends accept me as I am, (c) My friends are easy to talk to, and (d) My friends respect my feelings. For each item, students were given corresponding response options with a four-point scale: 1 for “Almost never or never true”, 2 for “Sometimes true”, 3 for “Often true”, and 4 for “Almost always or always true”. Higher scores demonstrated better friendship quality. Cronbach’s α = 0.90.

Mental well-being

Mental well-being (MWB) was assessed by the WHO-5 well-being measure in SSES 2019. Corresponding indices were derived from five well-being-related statements. Students were asked to express how they had been feeling over the past two weeks: (a) Felt cheerful and in good spirits, (b) Felt calm and relaxed, (c) Felt active and vigorous, (d) Woken up feeling fresh rested, and (e) Daily life has been filled with things that interest me. Students were given options on a five-point scale to indicate how often these situations occurred: 1 for “at no time”, 2 for “some of the time”, 3 for “more than half of the time”, 4 for “most of the time”, as well, 5 for “all of the time”. Higher scores embodied more mental well-being. Cronbach’s α = 0.88.

Analytical procedures

In the current study, the data were analyzed with Mplus 8.3 software (Muthen and Muthen 1998–2019). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation model (SEM) were estimated by maximum likelihood estimation with the robust standard errors (MLR) method. In order to test for mediation effects, the bootstrapping bias-corrected confidence interval procedure was applied with 10,000 bootstrap samples (Hayes 2009). Furthermore, measurement invariance was used to examine whether the same model fit for China versus Canada, and the multiple-group analysis was used to determine whether the structural paths performed differently for the two countries. Given that the Chi-Square statistic is sensitive to sample size, the model fitness indices used were CFI and TLI with satisfied values more than 0.90, as well as RMSEA and SRMR with accepted standards less than 0.08 (Bollen 1989; Hooper et al. 2008; Kline 2005).

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all study variables, showing that participants from China had a higher mean than Canada on self-control (M = 3.654, SD = 0.432 for China; M = 3.514, SD = 0.449 for Canada), empathy (M = 3.838, SD = 0.423 for China; M = 3.741, SD = 0.572 for Canada), and interpersonal trust (M = 3.626, SD = 0.669 for China; M = 3.214, SD = 0.640 for Canada). However, Canadian participants had higher scores than the Chinese on friendship quality (M = 3.008, SD = 0.587 for China; M = 3.174, SD = 0.632 for Canada) and mental well-being (M = 2.984, SD = 0.789 for China; M = 2.993, SD = 0.814 for Canada). Regarding the covariates, it was found that the number of males is more than that of females for both Chinese and Canadian participants, and that the Canadian participants had higher SES scores than the Chinese.

Measurement model evaluation

The fit indices of the measurement model for the aggregate sample (N = 5651) indicated that χ2 = 2208.324, df = 220, RMSEA = 0.040, CFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.945, and SRMR = 0.044, suggesting that the measurement model fit the data adequately (Hooper et al. 2008; Kline 2005). As seen in Table 2, the bivariate correlations for all constructs were significant at the alpha level of 0.001, and the correlation coefficients ranged from 0.213 to 0.512, indicating that further analyses would be appropriate (Kline 2005). Regarding the covariates, both gender and SES were significantly correlated with scores on all constructs, whereas gender and SES were not significantly correlated. Furthermore, as shown in Table 3, the standardized estimates of the items for all constructs, which ranged from 0.513 to 0.860 were statistically significant at the 0.001 level.

Structural model evaluation

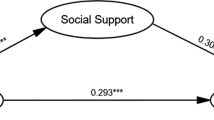

The structural model for the entire sample (N = 5651) displayed a satisfactory fit (χ2 = 2640.722, df = 262, RMSEA = 0.040, CFI = 0.945, TLI = 0.937, SRMR = 0.045), reflecting that found in previous studies (Hooper et al. 2008; Kline 2005). The results of the structural model evaluation are demonstrated in Fig. 2 and Table 4. Both gender and SES were significantly associated with friendship quality and mental well-being. The findings showed that boys have higher mental well-being whereas girls scored higher in friendship quality, and that participants with higher SES have a higher-quality friendship and more mental well-being. Although self-control (β = −0.011, p > 0.05) had no significant effect on friendship quality, both empathy (β = 0.197, p < 0.001) and interpersonal trust (β = 0.354, p < 0.001) were positively linked to friendship quality. Also, friendship quality (β = 0.151, p < 0.001), self-control (β = 0.117, p < 0.001), empathy (β = 0.085, p < 0.001), and interpersonal trust (β = 0.342, p < 0.001) were all significantly and positively associated with mental well-being.

Mediation analysis

As suggested by Hayes (2009), an indirect effect can be significant when zero is not found between the lower and upper boundaries in the 95% confidence interval (CI). As seen in Table 4, the effect of empathy on mental well-being was significantly mediated by friendship quality (β = 0.030, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.021, 0.039]), and friendship quality was also a significant mediator of the relationship between interpersonal trust and mental well-being (β = 0.054, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.041, 0.066]). However, the path effect of self-control on mental well-being via friendship quality was not significant (β = −0.002, p > 0.05, 95% CI [−0.008, 0.004]). In addition, the bootstrap analysis indicated that the indirect effects of empathy and interpersonal trust on mental well-being via friendship quality accounted for 26.3% and 13.7% of the corresponding total effects, respectively.

Multiple-group analysis

Measurement invariance was first assessed for China versus Canada in order to verify the potential moderating effects of country. Bollen (1989) noted that measurement invariance is a matter of degree in that researchers decide which parameters should be tested, and to what extent and in what order these tests should be performed for group comparison. Based on the means of partial measurement invariance in the current study, configural invariance and metric invariance were supported, indicating that the two groups (China and Canada) shared the same factor pattern, that items were identical per construct, and that the patterns of factor loadings were equal for China and Canada. Therefore, subsequent multiple-group analyses were shown to be appropriate (Ghasemy and Elwood 2023; Schmitt and Kuljanin 2008; Yang et al. 2021).

Table 5 displays the results of the multi-group analysis. The effects of empathy (βDifference = 0.145, p < 0.01) and interpersonal trust (βDifference = −0.161, p < 0.001) on friendship quality were significantly different across China and Canada. Empathy was positively associated with adolescent mental well-being for China (βChina = 0.116, p < 0.01) but not for Canada (βCanada = 0.051, p > 0.05), although no significant differences were found between the two countries. Meanwhile, some differences were revealed for the paths of gender to friendship quality (βDifference = 0.059, p < 0.05) and mental well-being (βDifference = −0.100, p < 0.001), as well as SES to friendship quality (βDifference = 0.082, p < 0.01) and mental well-being (βDifference = 0.051, p < 0.05). Specifically, there was a significantly greater difference regarding friendship quality and mental well-being for boys versus girls in Canada than there was in China; SES showed a significantly stronger effect on friendship quality in China than in Canada, and SES was significantly associated with Chinese but not Canadian mental well-being.

Discussion

The present study investigated associations between self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being among adolescents in both China and Canada. We first constructed four hypotheses based on the extant literature, where H2 and H3 were fully supported, whereas H1 and H4 were only partially supported. The prediction for H5 was formed to verify the potential moderating effect of the country. The empirical analysis indicated that H5b, H5c, and H5f remain relevant, whereas the remaining H5 items are rejected. Within the aggregate sample, it was found that empathy and interpersonal trust are positively related to mental well-being both directly and indirectly, with friendship quality as a mediator; these findings support those of previous studies (e.g., Clarke et al. 2021; Hecht et al. 2022; Helliwell and Wang 2011; Jakovljevic 2018; Kim et al. 2012; Martinez et al. 2019; Zhou et al. 2020). Self-control had only a direct effect on mental well-being due to the non-significant association between self-control and friendship quality, reflecting certain findings (e.g., Boals et al. 2011; Converse et al. 2018; Gokalp 2023; Kim et al. 2022) but not others (Boman et al. 2012; Boman et al. 2019). Furthermore, multiple-group analysis revealed a series of discrepancies between Chinese and Canadian participants regarding these associations.

The greatest difference between China and Canada was captured in the relationship between empathy and mental well-being. While empathy had no significant effect on the mental well-being of Canadian adolescents, it was significantly and positively associated with Chinese adolescents’ mental well-being. Research has shown that empathy exerts different influences on personal affections and social interactions across collectivist and individualist cultural settings (Duan et al. 2008; Heinke and Louis 2009). Chinese culture is rooted in collectivism, which underscores group consciousness, social identity, emotional dependence, perspective taking, and understanding and sharing, which in turn are closely associated with positive psychological experience and emotional interaction (Hofstede 2001; Mann and Cheng 2013). Furthermore, inheriting of the ancient Confucian ethic, Chinese adolescents are expected from an early age to show altruistic behaviors towards and emotional interdependence with the people with whom they interact (Gummerum and Keller 2008; Huang et al. 2018). Therefore, it is not surprising that empathy plays a fundamental role in Chinese adolescents’ social relationships and well-being (Huang and Su 2014; Huang et al. 2018). Conversely, individualistic societies such as is found in Canada tend to espouse values such as personal consciousness, emotional independence, and life autonomy, and due to a focus on privacy and non-interference, empathic concern may not be regarded as contributing value to individuals’ affective interactions and well-being (Duan et al. 2008; Hofstede 2001; Rubin et al. 2006).

The findings also showed a significant difference, stronger among Chinese adolescents than among Canadians, in the relationship between empathy and friendship quality. This result could be interpreted with regard to previous studies, suggesting that reciprocally emotional interaction and empathic concern have a more intense impact on friendship quality in collectivistic rather than individualistic cultures (Gummerum and Keller 2008; Huang and Su 2014). However, individualist people like Canadians generally emphasize private, affective, and hedonistic considerations when establishing friendships, whereas Chinese adolescents are predominantly motivated by empathic-altruistic concerns for any newcomers (Chen et al. 2004; Gummerum and Keller 2008). Furthermore, similar results to ours were obtained by Chen et al. (2004). In comparison with Chinese boys, Canadian boys usually score higher in self-worth but lower in understanding, care, and instrumental assistance when establishing friendships (Chen et al. 2004). Moreover, an inverse association between emotional empathy and peer acceptance has been found in a Western Canadian sample of adolescents, indicating that being emotionally expressive in the form of empathy is probably considered to be undesirable or “uncool” for this group (Oberle et al. 2010). The findings, therefore, suggest that empathy is more likely to be apparent in adolescents’ friendships in China than in Canada.

Consistent with our expectations, the relationship between interpersonal trust and friendship quality was significant, with a stronger association for Canadian than for Chinese adolescents. This finding may probably be attributed to different implications of friendship and distinct roles of trust for the Chinese versus the Canadians. As opposed to the view of “friendship as therapy” in Western societies like Canada, friendships in China have a particular emphasis on mutual responsibility and social stability as set out in Confucian philosophy (Gummerum and Keller 2008). Unlike in an individualistic society, children in China are encouraged to value the collective zeitgeist, for example, as regards social identity, and interpersonal trust may also derive from adherence to social norms (Guo et al. 2022; Seeley and Gardner 2003). Actually, people in a collectivist society often form friendships out of common group benefits, regarding friendship as a way of integrating into the societal system (Gummerum and Keller 2008), with a relatively weaker effect of interpersonal trust on their friendship quality. While traditional individualism in Canada does not support the forming of the heart-to-heart interpersonal exchanges that are found in the Chinese collectivist context: Trust is relatively shallow in individualist societies, linked as it is to personal preferences and disposition (Gummerum and Keller 2008; Guo et al. 2022; Rubin et al. 2006). Therefore, when Canadian adolescents choose friends, interdependent trust is probably more important than it is for Chinese. In fact, much research has shown that individualism is indicative of a more extensive trust radius, which exerts greater effects on social interactions, peer relationships, and even global well-being (Guo et al. 2022; Luo et al. 2023; van Hoorn 2015).

Unexpectedly, we found that self-control did not have a significant association with friendship quality, and the expected indirect effect of self-control on mental well-being via friendship quality was also non-significant for both Chinese and Canadian participants. Such a finding may be attributed to the unique developmental stage of adolescence: Regarding the link between self-control and friendship quality, our findings may reflect that biological factors outweigh cultural factors (Ronen et al. 2016; Steinberg and Morris 2001). From the cognitive psychology perspective, adolescence is distinguished by dramatic physical, psychological, and personal transformation, where cognition becomes confused, intricate, unquestioning, and even imprudent (Erikson 1950; Steinberg and Morris 2001). Unlike adults, adolescents may make friends more subjectively, according to their feelings and preferences, rather than others’ beneficial traits such as control, conscientiousness, and conformity (Akers et al. 1998; Shulman et al. 1997; Steinberg and Morris 2001). Findings suggest that in adolescence, the tolerance of others’ individuality increases, whereas control and conformity in friendship decreases, thereby showing a relatively weak effect of control on friendships (Shulman et al. 1997). Therefore, when discussing the association between self-control and adolescent friendship quality, researchers should account for such cognitive propensities.

With regard to the effect of covariates on friendship quality and mental well-being, the results showed that the greatest difference between China and Canada was found in terms of the association between SES and mental well-being. SES had a positive effect on Chinese adolescents’ mental well-being but had no significant impact on Canadians’ mental well-being. This finding supports the view that the effect of income on well-being varies across societies (Haller and Hadler 2006; Zagorski 2011). Haller and Hadler (2006) suggested that income has merely a small effect on well-being in high-income countries. Using an international comparative perspective, Zagorski (2011) proposed that high-income societies usually demonstrate a weaker association between income and well-being than that found in low-income societies. In comparison with China, Canada is considered a wealthy society where people generally have large incomes. Therefore, SES may be more likely to exert a significant impact on the mental well-being of Chinese than on Canadian adolescents, reflecting the regulation of diminishing marginal utilities of income, as well.

Implications, limitations, and future directions

Self-control, empathy, and interpersonal trust, three crucial components in the construct of social and emotional skills (OECD 2019), were used in our model to examine their effects on adolescent friendship quality and mental well-being. Although social and emotional skills may be effective in improving positive outcomes in a particular country, they may not be as effective in another (Miyamoto et al. 2015). Cross-national discrepancies in the impact of social and emotional skills are likely to be derived from differences in cultural contexts; thus, the exploration regarding potential associations among these social-emotional variables, based on their cultural-specific meanings, is required. Overall, our findings suggest some social and practical implications for policy application in social-emotional-related education as well as for the improvement of well-being for Chinese and Canadian adolescents.

Firstly, given that social-emotional learning has been highly recommended by both Chinese and Canadian policymakers in recent years (Tze et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2017), they could potentially consider organizing cultural-specific social-emotional learning, rather than applying a global construct (e.g., the Big Five) to their educational practices. For instance, empathy not only has a significant effect on the mental well-being of Chinese adolescents but not on that of Canadian adolescents but also exerts a relatively stronger impact on adolescent friendship quality in China than in Canada. Thus, empathic training could be considered more valuable for Chinese adolescents. Strengthening interpersonal closeness by blurring and expanding group boundaries, and experiencing emotional regulation in social interactions have both been shown to enhance adolescent empathic competency (Levine et al. 2005; Zaki 2020). In addition, since interpersonal trust has a significantly stronger effect on friendship quality for Canadian than for Chinese adolescents, interpersonal trust in social-emotional-related education may have a stronger effect on Canadian adolescent friendship quality. In fact, it is harder to develop trust in China versus individualist Canada because of the collectivist culture’s emphasis from tight-knit groups on in-group boundaries and social control (Jasielska et al. 2018). Therefore, cross-group interactions should be salient in order to extend the interpersonal trust radius for Chinese adolescents.

Secondly, considering the significant impact that we found of SES on Chinese adolescents’ mental well-being, policymakers might be encouraged to enact regulations that favor the mental well-being of disadvantaged students from low-income homes or rural areas in China. Previous research suggests that the level of individuals’ economic well-being depends on social comparison, that is, as perceived relative income rather than absolute income (Easterlin 2001). Therefore, reasonable assistance policies should be employed to provide sufficient financial subsidies for students with low SES in China, a practice which would also have the effect of narrowing the family income gap to some extent. Although the Chinese financial support system in education has been gradually designed since the early 21st century to mitigate educational inequalities, it leaves room for improvement (Li and Xue 2022). Financial assistance in Chinese elementary education schools generally comprises a unified management system, without considering the specific requirements of individuals in need of funding. Therefore, targeted poverty alleviation should be effectively implemented in the Chinese educational context.

Our study performed a range of analyses of measurement invariance that explored certain associations among self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being by country, and we have discussed the structural relationships of these variables for Chinese and Canadian adolescents from a cross-cultural perspective of collectivism and individualism. Our study contributes to the literature in certain ways, as follows: The findings address gaps in the existing literature and provide scientific evidence for enhancing adolescent mental well-being across different cultural contexts. In addition, statistical tests employed in the study are of relatively high quality, and we used a large-scale sample size with a well-balanced gender representation.

Our study also has several limitations that need to be addressed in future research. Firstly, given that the present findings were based on cross-sectional data gathered in SSES 2019, the potential causal inferences cannot be explored. Therefore, robust longitudinal research designs should be employed in future research to examine causality. Secondly, the variables of self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being were all reported by students in the current study. Future research should gather data from the perspectives of teachers and peers to limit or remove social desirability effects. Thirdly, we selected only 15-year-old adolescents as the sample so could not test potential cross-group differences in age. Future studies could investigate the structural relationships of these variables using an analysis of invariance according to different age groups. Fourthly, our cross-national comparison was based on only Chinese and Canadian samples, so future comparative studies could contain more Eastern and Western countries to further examine the relationships among these variables. Such a test may promote a mutual and in-depth understanding of the structural relationships among self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being across different cultural contexts.

Conclusions

The present study explored the structural relationships among self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being among Chinese and Canadian adolescents, and the results were discussed from the cross-cultural perspective of collectivism versus individualism. Previous studies tended to examine similar associations by comparing regression coefficients for each cultural group separately. Using a multi-group analytic approach within SEM, we conducted a simultaneous test of the structural relationships for the five variables for China and Canada which represent Eastern and Western cultures, respectively. The results indicate that, within the aggregate sample, self-control has only a direct impact on mental well-being, whereas empathy and interpersonal trust relate to mental well-being both directly and indirectly, with friendship quality as a mediator. In addition, the multiple-group analysis revealed that empathy exerts a positive effect on Chinese adolescents’ mental well-being but not Canadians’. Although empathy had a significantly stronger effect on friendship quality for Chinese than for Canadian adolescents, interpersonal trust exerted a significantly stronger effect on friendship quality for Canadian than for Chinese adolescents. Critically, our findings suggest that the structural relationships of self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being may differ according to individuals’ subject preferences, specific values, and social beliefs. Therefore, further research that examines potential associations among these variables and that is based on specific cultural settings is required.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the 2019 Survey on Social and Emotional Skills (SSES 2019) repository, https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/social-emotional-skills-study/.

References

Akers JF, Jones RM, Coyl DD (1998) Adolescent friendship pairs: similarities in identity status development, behaviors, attitudes, and intentions. J Adolesc Res 13(2):178–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743554898132005

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

van den Bedem NP, Willems D, Dockrell JE, van Alphen PM, Rieffe C (2019) Interrelation between empathy and friendship development during (pre)adolescence and the moderating effect of developmental language disorder: a longitudinal study. Soc Dev 28(3):599–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12353

Bernerth JB, Aguinis H (2016) A critical review and best practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers Psychol 69(1):229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103

Betts LR, Rotenberg KJ (2007) Trustworthiness, friendships and self-control: factors that contribute to young children’s school adjustment. Infant Child Dev 16(5):491–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.518

Boals A, Vandellen MR, Banks JB (2011) The relationship between self-control and health: the mediating effect of avoidant coping. Psychol Health 26(8):1049–1062. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2010.529139

Bollen KA (1989) Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley, New York, https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118619179

Boman JH, Krohn MD, Gibson CL, Stogner JM (2012) Investigating friendship quality: an exploration of self-control and social control theories’ friendship hypotheses. J Youth Adolesc 41(11):1526–1540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9747-x

Boman JH, Mowen TJ, Castro ED (2019) The relationship between self-control and friendship conflict: an analysis of friendship pairs. Crime Delinq 65(10):1402–1421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128718765391

Bray M, Adamson R, Mason M (2014) Comparative education research, approaches and methods, 2nd edn. Springer, Hong Kong, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05594-7

Carver CS, Scheier MF (1981) Attention and self-regulation: a control-theory approach to human behavior. Springer-Verlag, New York, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-5887-2

Chen X, Kaspar V, Zhang Y, Wang L, Zheng S, Way N, Chu JY (2004) Peer relationships among Chinese and North-American boys: a cross-cultural perspective. Adolescent boys: exploring diverse cultures of boyhood. New York University Press, New York, p 197–218

Ciarrochi J, Parker PD, Sahdra BK, Kashdan TB, Kiuru N, Conigrave J (2017) When empathy matters: the role of sex and empathy in close friendships. J Pers 85(4):494–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12255

Clarke A, Meredith PJ, Rose TA (2021) Interpersonal trust reported by adolescents living with mental illness: a scoping review. Adolesc Res Rev 6(2):165–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-020-00141-2

Collie RJ (2022) Instructional support, perceived social-emotional competence, and students’ behavioral and emotional well-being outcomes. Educ Psychol 42(1):4–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2021.1994127

Converse PD, Beverage MS, Vaghef K, Moore LS (2018) Self-control over time: implications for work, relationship, and well-being outcomes. J Res Pers 73:82–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.11.002

Davis MH (1996) Empathy: a social psychological approach. Westview Press, Boulder, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429493898

Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L (2018) Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Hum Behav 2(4):253–260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

Duan C, Wei M, Wang L (2008) The role of individualism-collectivism in empathy: an exploratory study. Asian J Couns 15(1):57–81

Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB (2011) The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Dev 82(1):405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

Easterlin RA (2001) Income and happiness: towards a unified theory. Econ J 111:465–484. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0297.00646

Erikson EH (1950) Childhood and society. W. W. Norton, New York

Ghasemy M, Elwood JA (2023) Job satisfaction, academic motivation, and organizational citizenship behavior among lecturers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-national comparative study in Japan and Malaysia. Asia-Pac Educ Rev 24(3):353–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09757-6

Gokalp ZS (2023) Examining the association between self-control and mental health among adolescents: the mediating role of resilience. Sch Psychol Int. https://doi.org/10.1177/01430343231182392

Gummerum M, Keller M (2008) Affection, virtue, pleasure, and profit: developing an understanding of friendship closeness and intimacy in western and Asian societies. Int J Behav Dev 32(3):218–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408089271

Guo Q, Zheng W, Shen J, Huang T, Ma K (2022) Social trust more strongly associated with well-being in individualistic societies. Pers Individ Differ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111451

Haller M, Hadler M (2006) How social relations and structures can produce happiness and unhappiness: an international comparative analysis. Soc Indic Res 75(2):169–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-004-6297-y

Hayes AF (2009) Beyond Baron and Kenny: statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun Monogr 76(4):408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360

Hecht M, Kloss A, Bartsch A (2022) Stopping the stigma. How empathy and reflectiveness can help reduce mental health stigma. Med Psychol 25(3):367–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2021.1963991

Heinke MS, Louis WR (2009) Cultural background and individualistic-collectivistic values in relation to similarity, perspective taking, and empathy. J Appl Soc Psychol 39(11):2570–2590. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00538.x

Helliwell JF, Wang S (2011) Trust and wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing 1:42–78. https://doi.org/10.3386/w15911

Hofmann W, Luhmann M, Fisher RR, Vohs KD, Baumeister RF (2014) Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. J Pers 82(4):265–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12050

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00184-5

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR (2008) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Elec J Bus Res Methods 6(1):53–60. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7CF7R

van Hoorn A (2015) Individualist-collectivist culture and trust radius. J Cross Cult Psychol 46(2):269–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114551053

van der Horst M, Coffé H (2011) How friendship network characteristics influence subjective well-being. Soc Indic Res 107:509–529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9861-2

Huang H, Su Y (2014) Peer acceptance among Chinese adolescents: the role of emotional empathy, cognitive empathy and gender. Int J Psychol 49(5):420–424. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12075

Huang J, Shi H, Liu W (2018) Emotional intelligence and subjective well-being: altruistic behavior as a mediator. Soc Behav Pers 46(5):749–758. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6762

Jakovljevic M (2018) Empathy, sense of coherence and resilience: bridging personal, public and global mental health and conceptual synthesis. Psychiatr Danub 30(4):380–384. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2018.380

Jasielska D, Stolarski M, Bilewicz M (2018) Biased, therefore unhappy: disentangling the collectivism-happiness relationship globally. J Cross Cult Psychol 49(8):1227–1246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118784204

Kim S-S, Chung Y, Perry MJ, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV (2012) Association between interpersonal trust, reciprocity, and depression in South Korea: a prospective analysis. PLoS ONE 7(1):e30602. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030602

Kim YY, Richards JS, Oldehinkel AJ (2022) Self-control, mental health problems, and family functioning in adolescence and young adulthood: between-person differences and within-person effects. J Youth Adolesc 51(6):1181–1195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01564-3

Kirkwood T, Bond J, May C, McKeith I, Teh M (2008) Foresight mental capital and wellbeing project. Mental capital through life: future challenges. The Government Office for Science, London

Kline RB (2005) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Kong XJ, Cui LJ, Li JC, Yang Y (2022) The effect of friendship conflict on depression, anxiety and stress in Chinese adolescents: the protective role of self-compassion. J Child Fam Stud 31(11):3209–3220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02413-y

Levine M, Prosser A, Evans D, Reicher S (2005) Identity and emergency intervention: how social group membership and inclusiveness of group boundaries shape helping behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31(4):443–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271651

Li J, Xue E (2022) Unpacking the policies, historical stages, and themes of the education equality for educational sustainable development: evidence from China. Sustain 14(17):10522. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710522

Li QQ, Tan YY, Chen Y, Li C, Ma XQ, Wang LX, Gu CH (2021) Is self-control an “angel” or a “devil”? The effect of internet game disorder on adolescent subjective well-being. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 25(1):51–58. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0044

Luo SY, Li LMW, Espina E et al. (2023) Individual uniqueness in trust profiles and well-being: understanding the role of cultural tightness-looseness from a representation similarity perspective. Br J Soc Psychol 63(2):825–844. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12599

Lwasaki M (2023) Social preferences and well-being: theory and evidence. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):342. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01782-z

Mann SKF, Cheng V (2013) Responding to moral dilemmas: the roles of empathy and collectivist values among the Chinese. Psychol Rep 113(1):107–117. https://doi.org/10.2466/17.21.PR0.113x14z6

Martinez LM, Estrada D, Prada SI (2019) Mental health, interpersonal trust and subjective well-being in a high violence context. SSM-Pop Health 8:100423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100423

Mayer RC, Davis JH, Schoorman FD (1995) An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad Manag Rev 20(3):709–734. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1995.9508080335

Miething A, Almquist YB, Edling C, Rydgren J, Rostila M (2017) Friendship trust and psychological well-being from late adolescence to early adulthood: a structural equation modelling approach. Scand J Public Health 45(3):244–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494816680784

Miyamoto K, Huerta MC, Kubacka K (2015) Fostering social and emotional skills for well-being and social progress. Eur J Educ 50(2):147–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12118

Muthen LK, Muthen BO (1998) Mplus (Version 8.3) [Computer software]. Muthen & Muthen, Los Angeles, CA, 2019

Oberle E, Schonert-Reichl KA, Thomson KC (2010) Understanding the link between social and emotional well-being and peer relations in early adolescence: gender-specific predictors of peer acceptance. J Youth Adolesc 39:1330–1342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9486-9

OECD (2019) Assessment Framework of the OECD Study on Social and Emotional Skills. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5007adef-en.pdf

OECD (2021) OECD Survey on Social and Emotional Skills Technical Report. https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/social-emotional-skills-study/sses-technical-report.pdf

Park N, Huebner ES (2005) A cross-cultural study of the levels and correlates of life satisfaction among adolescents. J Cross Cult Psychol 36:444–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022105275961

Poulin MJ, Haase CM (2015) Growing to trust: evidence that trust increases and sustains well-being across the life span. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 6(6):614–621. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615574301

de Ridder D, Gillebaart M (2017) Lessons learned from trait self-control in well-being: making the case for routines and initiation as important components of trait self-control. Health Psychol Rev 11:89–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2016.1266275

de Ridder DT, Lensvelt-Mulders G, Finkenauer C, Stok FM, Baumeister RF (2012) Taking stock of self-control: a meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 16(1):76–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868311418749

Ronen T, Hamama L, Rosenbaum M, Mishely-Yarlap A (2016) Subjective well-being in adolescence: the role of self-control, social support, age, gender, and familial crisis. J Happiness Stud 17(1):81–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9585-5

Rotter JB (1967) A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J Pers 35(4):651–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x

Rubin KH, Hemphill SA, Chen X et al. (2006) A cross-cultural study of behavioral inhibition in toddlers: east-west-north-south. Int J Behav Dev 30:219–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025406066723

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2001) On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141

Schmitt N, Kuljanin G (2008) Measurement invariance: review of practice and implications. Hum Resour Manag Rev 18(4):210–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.03.003

Schreiter S, Pijnenborg GHM, Aan Het Rot M (2013) Empathy in adults with clinical or subclinical depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord 150(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.03.009

Seeley E, Gardner WL (2003) The “selfless” and self-regulation: the role of chronic other-orientation in averting self-regulatory depletion. Self Identity 2:103–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309034

Sened H, Lavidor M, Lazarus G, Bar-Kalifa E, Rafaeli E, Ickes W (2017) Empathic accuracy and relationship satisfaction: a meta-analytic review. J Fam Psychol 31(6):742–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000320

Shulman S, Laursen B, Kalman Z, Karpovsky S (1997) Adolescent intimacy revisited. J Youth Adolesc 26:597–617. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024586006966

Steinberg L, Morris AS (2001) Adolescent development. J Cogn Educ Psychol 2(1):55–87. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.83

Stewart WC, Reynolds KE, Jones LJ, Stewart JA, Nelson LA (2015) The source and impact of specific parameters that enhance well-being in daily life. J Relig Health 55(4):1326–1335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-015-0076-8

Tze VMC, Li JC-H, Daniels LM (2022) Similarities and differences in social and emotional profiles among students in Canada, USA, China, and Singapore: PISA 2015. Res Pap Educ 37(4):560–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1864760

Wang S, Dong X, Mao Y (2017) The impact of boarding on campus on the social-emotional competence of left-behind children in rural western China. Asia-Pac Educ Rev 18:413–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-017-9476-7

Wei M, Liao KY-H, Ku T-Y, Shaffer PA (2011) Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. J Pers 79(1):191–221. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x

Wills TA, Simons JS, Sussman S, Knight R (2016) Emotional self-control and dysregulation: a dual-process analysis of pathways to externalizing/internalizing symptomatology and positive well-being in younger adolescents. Drug Alcohol Depend 163:37–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.08.039

Yang YC, Qin LX, Ning L (2021) School violence and teacher professional engagement: a cross-national study. Front Psychol 12:628809. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.628809

Zagorski K (2011) Income and happiness in time of post-communist modernization. Soc Indic Res 104(2):331–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9749-6

Zaki J (2020) Integrating empathy and interpersonal emotion regulation. Annu Rev Psychol 71(1):517–540. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050830

Zhang RJ (2020) Social trust and satisfaction with life: a cross-lagged panel analysis based on representative samples from 18 societies. Soc Sci Med 251:112901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112901

Zhou XC, Li J, Wang Q (2020) Making best friends from other groups and mental health of Chinese adolescents. Youth Soc 54(1):123–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X20959222

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JN and CJ: conceptualization, methodology, software, supervision, validation, writing—original draft, and writing—reviewing and editing. LM: conceptualization, writing—original draft, and writing—reviewing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval

The international organization OECD has completed the ethical norm for all participating countries/economies in the 2019 Survey on Social and Emotional Skills (SSES 2019).

Informed consent

Informed consent for all individual participants in the study has been officially completed by the international organization OECD.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niu, J., Jin, C. & Meng, L. The structural relations of self-control, empathy, interpersonal trust, friendship quality, and mental well-being among adolescents: a cross-national comparative study in China and Canada. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 929 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02468-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02468-2