Abstract

The article discusses the role of digital media use in societal transformations, with a specific focus on the emergence of micro-identities. It also explores the extent to which such transformations entail increasing the risk of societal disintegration—defined as the erosion of established social structures, values, and norms. Our contention is that the distinctive attributes of digital media, coupled with the myriad expanding opportunities of use they afford, harbor the potential to fragment and polarize public discourse. Such tendencies jeopardize public trust in democratic institutions and undermine social cohesion. The intricate interplay between media usage and polarization synergistically contributes to the formation of micro-identities, characterized by their narrow and emergent nature. These micro-identities, in turn, manifest themselves through in-group self-determination often to the detriment of the broader social fabric. Thus, various micro-identities may actively contribute to the actual atrophy of the implicit rules and procedures hitherto deemed the norm within society. By addressing these multifaceted issues, typically confined within distinct disciplinary silos, this analysis adopts a multidisciplinary approach. Drawing from perspectives in political science, sociology, psychology, and media and communication, this paper offers in-depth analyses of the interactions between social processes and media usage. In doing so, it contributes substantively to the ongoing discourse surrounding the factors driving societal disintegration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prevailing discourse among scholars identifies social and political polarization as a critical element contributing to the global “democratic recession” and the escalating populist discontent evident in both mature democracies such as the United States and France, and emerging ones like Poland and Hungary (Svolik, 2019; Norris & Inglehart, 2019). This heightened polarization poses a persistent long-term risk, as the underlying mechanisms may pave the way for real-world radicalization and extremism, reinforcing a pervasive narrative of intolerance and social disintegrationFootnote 1—characterized by the erosion of social structures, values, and norms. Numerous scholars have cautioned that the unique features of social media and digital platformsFootnote 2, coupled with their ever-expanding capabilities, have the potential to fragment and polarize public discourse (Kozyreva et al., 2020; Lewandowsky et al., 2013; 2023). This potential fragmentation, in turn, stands as a threat to public trust in democratic institutions and the stability of social cohesion (Mihailidis & Viotty, 2017; Strömbäck et al., 2022; Törnberg, 2022; Yarchi et al., 2021).

In this paper, we focus on the intricate interplay between media usage and polarization, elucidating the resultant emergence of diverse micro-identities. These micro-identities are characterized by their narrow and emergent nature, marked by distinct epistemic realities, unwavering internal support for their ideology and activities, and in-group self-determination at the expense of the broader society (Fukuyama, 1992; 2019). As a result, we regard social media and digital platforms as catalysts of polarization, functioning as sorting mechanisms that expedite the process of micro-identity formation and their noticeable differentiation from outgroups. Nonetheless, it appears that the mechanism potentially explaining the influence of social media use on the dynamic progression from individual psychological needs to shared narratives, and, in turn, to network processes with potential societal impact is incomplete and largely insufficient (Bor & Petersen, 2022).

A lens on these dynamics, however, was provided by the COVID-19 pandemic, during which the impact of media usage on various social processes became evident. Specifically, the use of media platforms served to mobilize and activate the gathering of potential followers within specific groups. Initially, these platforms facilitated the emergence of distinct microgroups for various purposes including social support and community exchange. However, a notable subset of these groups was fueled by conspiracy theories (Dow et al., 2021; Latikka et al., 2022). Subsequently, the pandemic’s capacity to impede human interactions in the real world was compounded by the effect of retreating into, and being cocooned within, safe digital bubbles comprised of micro-identities. Prominent examples of such communities include antivaxxers, Incels, conspiracy theorists, and extreme religious groups (Campbell & Golan, 2011; Yang et al., 2021). Throughout the protracted lockdowns and extensive social distancing, social media and digital platforms, which had already established themselves as alternative (or additional) social spaces catering to individuals seeking alternative (or additional) identities and a sense of community, began to supersede and supplant traditional family, neighborhood, and peer communities (Guess et al., 2021). This enclosure within micro-identities represents a somewhat paradoxical outcome resulting from the weakening of human connections and the escalating societal fragmentation witnessed in recent years (Strömbäck, 2015).

While the topic itself is not entirely novel, the role of social media use in these social processes remains only partly elucidated (Lewandowsky et al., 2020; Theocharis et al., 2023). Moreover, the socio-cognitive underpinnings of (social) media-related phenomena are seldom considered (Lüders et al., 2022). Therefore, in this paper, we present an integrative theoretical framework detailing how individuals’ motivation and processes of social influence may interact with media use, giving rise to virtual loyalties (micro-identities), and the construal of parallel social realities that lack cohesion with the larger community. Fig. 1 illustrates our concept, depicting the interconnectedness of different ideas and outlining the theoretical functional relationships that can be tested through a research program. These topics, frequently explored within individual social science disciplines, are approached in this paper through a multidisciplinary lens. Additionally, we outline potential avenues for future research and propose recommendations to mitigate the polarizing and disintegrating effects of social media and digital platform use.

Digital world: algorithmic exposure and online active behavior

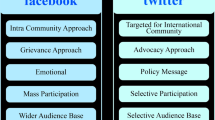

In the current online climate, it may be difficult to recall that, just a decade or so ago, in 2009, following Barack Obama’s victory in the US presidential election, and after the Arab Spring of 2010, many social researchers, and most journalists, foresaw the triumph of, or at least the gradual diffusion of, democracy throughout the world. These prognostications emphasized the pivotal role of the younger generation, particularly digital natives (Prensky, 2001), whose engagement in political discourse taking place on social media sites like Facebook and Twitter, was deemed decisive for the democratization process (for an overview, see Persilly & Tucker, 2020). Undoubtedly, social media does empower freedom of expression, enabling citizens to question and critique political decisions while advocating for their rights. Hence, the expectation was that social media and online forums would—and ought to—serve as platforms for fostering and protecting democracy by encouraging and allowing individuals to take informed, rational political decisions (Jennings & Zeitner, 2003; Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2023).

It has been over a decade since those optimistic forecasts, and while internet-based pro-democratic activities certainly do have their place, the actual implications of social media use have, in several respects, proven to be much less promising than initially envisioned (Bail, 2021; Persilly & Tucker, 2020). What has transpired since those heady days is that pro-democratic movements, and their social significance, have started to wane in comparison to the impact of a type of messaging that shakes our democratic foundations and counters a sense of civic community. One of the many ongoing concerns being voiced revolves around the management of digital information disseminated to millions of citizens, primarily overseen by a handful of decision-makers or highly politically motivated individuals, who typically operate beyond the oversight of State or international institutions (Kozyreva et al., 2020; Lewandowsky et al., 2020; Lewandowsky & Pomerantsev, 2022; Leiser, 2019).

However, the flow of information in social media is not solely a deliberate top-down process; it is molded by a multitude of factors and forces. In reality, its currents are also shaped by the structural network mechanisms of the attention economy, wherein attention, or people’s focus and engagement, are regarded as valuable and limited resources (Wu, 2017). In this context, individuals’ attention is treated as a commodity that can be captured, sold, and traded, much akin to traditional economic resources such as money or goods (Ali et al., 2021). In the digital realm, where there is an overabundance of information and content, businesses and individuals must distinguish themselves and effectively engage users. Techniques like personalized advertising, clickbait, and social media algorithms are employed to capture and retain people’s attention in this competitive environment (Bail, 2021). Additionally, the flow of information is affected by the dissemination of misinformation/disinformation, impacting users’ views and attitudes, often irrespective of users’ intentions, especially in the domain of politics (Bail, 2021; Benkler et al., 2018; Bennett & Livingstone, 2021; Strömbäck, Boomgaarden et al., 2022).

Nevertheless, individuals are not mere passive recipients of data, buffeted by these digital media currents; rather, they actively engage with these platforms. Indeed, users, driven by salient motives, actively search for specific information, and connect with like-minded individuals (Escobar-Viera et al., 2018; Thorisdottir et al., 2019; Webster, 2014). This heightened use of social media expands people’s opportunities to inform and express themselves, share opinions and engage in communication with each other, thereby enabling them to develop novel multiple social ties (Tucker et al., 2017). While this phenomenon holds the potential to strengthen democratic processes, it also harbors a dark side.

Firstly, the advent of digital media has significantly weakened the influence of traditional media, thereby hollowing out the once-shared “common space” which served as a meeting ground where individuals from various societal segments and differing backgrounds could encounter each other, learn about one another, and access reliable and verified news reports about politics and society (Strömbäck, Boomgaarden et al., 2022; Persilly & Tucker, 2020). This holds despite the unclear extent to which news audiences have actually fragmented (Castro et al., 2022; Fletcher & Nielsen, 2017), with variations across countries and media systems. It is noteworthy, however, that social relationships and interactions play a significant role in shaping individuals’ perspectives.

Whereas, in the past, community engagement and discussions may have acted as balancing factors, today, people often derive their identity and meaning from online sources (Praet et al., 2022). The issue at hand extends beyond a simple contrast between digital media and traditional media, and, in any case, an in-depth comparison of the two lies beyond the scope of this paper. Here we focus on digital media platforms that offer the transformative potential for the creation of alternative identities, structures of relationships, and the construction of meaning.

Secondly, and of equal significance is the prevalence of misinformation and intentionally false and/or misleading information strategically disseminated on digital media platforms in a targeted manner in order to cause maximum impact (see overview by Ecker et al., 2022). Thirdly, social and digital media use has facilitated the expansion of politically alternative or partisan media seeking to advance specific political goals and narratives, catering to individuals searching for attitude-confirming news and views (Benkler et al., 2018; Holt et al., 2019). Lastly, it has become easier than ever for people to seek out and find information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs, reinforcing their current identities rather than broadening their knowledge and perspectives (Sunstein, 2007; for overview see also: Kossowska et al., 2022). Interestingly, media usage may have a detrimental impact on individuals’ tolerance for uncertainty and breed mistrust in the media, potentially having deleterious effects on society in the long term (Guess et al., 2021; Loxton et al., 2020). This holds true not least because attacks on news media are prevalent on certain platforms and digital media (Egelhofer et al., 2022; Figenschou & Ihlebaek, 2019).

Collectively, these transformations have contributed to an escalating divergence in the selection of media sources, which is further amplified through the use of algorithms across groups, based on factors such as individuals’ interests and attitudes. These dynamics may culminate in the formation of homogeneous clusters that insulate individuals from opposing perspectives, ultimately contributing to the polarization of opinions and their drift towards more extreme positions. Descriptors such as “echo chambers” (Jamieson & Cappella, 2008; Bruns, 2019), “filter bubbles” (Pariser, 2011) and “balkanization” (Sunstein, 2007) have been employed to encapsulate this process and its potential outcomes.

Surprisingly, research indicates that the majority of individuals do not reside in enclosed echo chambers or filter bubbles (e.g., Arguedas et al., 2022; Barnidge et al., 2023; Terren & Borge-Bravo, 2021; Guess et al., 2021). In fact, cross-cutting exposure is more prevalent than selective exposure to attitude-consistent and selective avoidance of attitude-challenging information (for a recent review, see Arguedas et al., 2022). Numerous factors have been identified that may (or may not) contribute to the creation of conditions conducive to echo-chamber formation, including discussion frequency, the presence of neutral or politicized topics, homophily (McPherson et al., 2001), group or network homogeneity (e.g., Strauß et al., 2020; Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2023), and affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2019). Building upon McLuhan’s ideas, Venturini (2022) suggests that digital media, with their emphasis on real-time communication, reintroduce oral-like characteristics into our primarily text-based, literate society. The speed and immediacy of digital communication platforms foster a sense of shared presence, participation and develop quasi-tribal bonds, allowing people to instantly connect, share information, and build collective identities, in a way not unlike the practices of oral cultures. Furthermore, cross-cultural variations may exist, with some countries experiencing more fragmented and polarized on-line media environments and media use compared to others (Castro et al., 2022; Fletcher & Nielsen, 2017; Humprecht et al., 2020). Counterintuitively perhaps, it turns out that exposure to diverse viewpoints does not necessarily lead toward moderation and away from polarization (Bail, 2021; Törnberg, 2022).

Social instability may stem from deficits in socially shared beliefs or from disagreements and conflict over the control of narratives, resources and/or power structures. Conflict can escalate as a result of polarized beliefs and attitudes, coupled with heightened perceptions that the current status quo is inappropriate and inadequate, or even that the extant power structures themselves are illegitimate (Guinote, 2017). The intensification of social movements in recent years through social media use, spanning from climate change to religious and political activism, exemplifies the constant striving to dominate the social landscape and even ascend to power.

Micro-identities as drivers of societal disintegration

While further research is essential to fully understand the phenomena of echo-chambers/filter bubbles and their antecedents, a crucial step towards understanding the role of social and digital media in the processes contributing to social instability involves the development of various micro-identities (see Lorenz-Spreen et al., 2023). The concept of micro-identities traces its lineage back to the works of Fukuyama (2019, 1992) and Tönnies (1887/1993), albeit indirectly in the latter case. In light of their contributions, a micro-identity can be defined as a subjective sense of belonging to an exceedingly narrow group, where members are bound together by their identification with specific elements of social reality and a fervent belief in their own uniqueness. In some cases, such groups assert possession of arcane knowledge hidden from the ignorant masses, who remain unaware of it, or claim to have undergone unique subjective experiences inaccessible to others. In the digital realm, micro-identities typically manifest as temporal and emergent entities with distinct epistemic realities, unwavering internal support for their ideology and activities, and in-group self-determination (Lüders et al., 2022). Such identities are often formed around fragmented, composite ideas and belief systems (Gartenstein-Ross et al.; 2023).

As emerging micro-identities and their new corresponding micronarratives continuously unfold, concurrently, established ones endure and undergo further evolution. This perpetual evolution occurs as individuals seek a sense of belonging, meaning and purpose within their worldviews. In other words, it is crucial to underscore that micro-identities do not inherently preclude the coexistence of other identities or affiliations, encompassing those rooted in religious, ethnic, and national contexts.

However, it is conceivable that a single micro-identity (among many identities) may take precedence and incite radical actions (Berger, 2018). For instance, a follower of fundamentalist Islam in Europe may construct their identity on the basis of Wahhabi ideology, viewing themselves as a “true Muslim”. The existence of this micro-identity, in theory, does not clash with the broader concept of Muslim identity, even though the majority of Muslims do not adhere to this radical Wahhabi version of Islam or may openly reject it. Still, this commonality with conventional religiosity by no means prevents this radical group from pursuing further action of its own; in fact, they may simply perceive other Muslims as being “unaware of their true identity” and work towards “raising their awareness” (e.g. Rashid 2003, Firro 2018). Evidently, two parallel processes are at play: the formation of a Muslim (minority) community across national borders (previously existing mainly in theory as the umma), and the emergence of distinct micro-identities within the community itself. Enhanced social media use not only accelerates but even materializes these types of processes, enabling them through its transformative capabilities. Notably, not only emergent groups but also traditionally separatist and closed ones (such as ultra-Orthodox groups in Israel) were found to navigate the benefits and dangers offered by social media by providing strongly regulated “safe spaces” (digital enclaves) for their members, attempting not only to maintain, but also to strengthen their enclaved culture via social media use (Campbell & Golan, 2011).

Micro-identity can be also interpreted as a type of social identity based more on the sense of being separate from the vast majority of people rather than on the sense of belonging to a specific minority group (see also Törnberg, 2022). Unlike identity broadly understood (Tajfel, 1979), micro-identities occur not only in the context of a person’s relationship to themselves (self-identification), but above all, in the context of the relationship to other people and the values and attitudes they represent. Hence, we observe the specific phenomenon of building a micro-identity on the foundation of opposition to or even hostility towards specific groups, ideologies, values, etc., and not solely on the basis of attitudes and values shared with others (Gerbaudo et al., 2023; Gartenstein-Ross et al.; 2023; Törnberg, 2022). This is evident in the phenomenon of micro-identity groups, such as anti-vaxxers, being relabeled as anti-Ukrainian groups in online forums (Dauksza & Sepioło, 2022). Similarly, individuals initially identified as black nationalists may adopt various racist and misogynist ideologies (Gartenstein-Ross et al., 2023).

The genesis of novel identities, notably the burgeoning prevalence of micro-identities, has coincided with an accelerated rate in technological advancements particularly within the sphere of social media and digital platform use (Higgins et al., 2021; Strömbäck, 2015). This technological trajectory has engendered precipitous and widespread interactions across a global communication network. As a result, the social fabric of modern states and nations is undergoing an incremental transformation, which, though often imperceptible, wields the potential to eviscerate the conventional conception of the State itself. Furthermore, the confluence of economic, political and cultural challenges, entwined with the dynamism of demographic changes and immigration flows, has the power to instigate a pervasive sense of insecurity among individuals (Eatwell & Goodwin, 2018). These multifaceted challenges collectively contribute, albeit incrementally, to the attenuation of public conviction in the efficacy of the traditional model of the State.

An exemplar of this complex interplay is that of partisanship, commonly conceptualized as a social identity (Tajfel, 1979). Individuals often cultivate a partisan identity that increasingly aligns with other social cleavages, such as ethnicity, gender, age, and place of residence, rendering it susceptible to salient fluctuations in the political landscape (West & Iyengar, 2022). At the same time, micro-identities can be rooted in prominent events that trigger a cascade of dissemination of information and commentary in social media, giving rise to the emergence of narratives and novel narrowly-defined identities (Scharfbillig et al., 2021). A case in point is evident in the context of EU integration, where entities like the Polish right-wing neo-paganist group ‘The Association for Tradition and Culture “Niklot”’ and the nationalist Slavic Movement of Polish Nationalists “Zadruga” have forged networks with neo-pagan nationalists from Nordic and Germanic countries. Likewise, the Polish radical party “Konfederacja” (The Confederation – Freedom and Independence), predominantly comprising individuals openly opposing mandatory vaccines and pandemic-related restrictions, exemplifies a micro-identity centered around COVID-19 narratives. Finally, the ideological policies of the once-ruling PiS party (Law and Justice Party) staunchly advocates for a “Christian Europe” and actively endeavors to build temporary, or more enduring, alliances with anti-Muslim parties in Western Europe, such as the National Rally in France, and Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Germany. This illustrates the intricate interplay between partisan narratives and ethnic identity, organized around, in this latter case, religion.

Notably, the aforementioned process extends beyond individuals or groups with specific religious or ideological affiliations; it encompasses those lacking such denominators as well. This phenomenon is particularly observable in the emergence or intensification of new social movements in the post-COVID era, alongside the reinvigoration of traditional movements (e.g., neo-Luddites, incels, conspiracy theorists, antivaxxers etc.) in newly-reformulated incarnations. These instances further exemplify the manifestation of the overarching process across diverse social contexts.

Socio-psychological underpinnings of micro-identity

In the preceding sections, this paper primarily explored the process of micro-identity development and its potential ramifications on societal disintegration through a socio-political and media lens. However, it is plausible that the factors driving societal disintegration also possess a strong motivational component, with research indicating a crucial role for the frustration of fundamental human needs (e.g., Kruglanski, 2019, 2021; Fiske, 2018; Pratto et al., 2006). When fundamental needs such as significance, certainty, belongingness, or freedom remain unfulfilled, individuals may undergo a motivational imbalance that that propels them towards specific ideologies and radical affiliations (see for overview: Kruglanski et al., 2021). As a consequence, unmet needs can amplify the effects of general mechanisms, such as the influence of digital media compared to traditional media, and play a substantial role in the phenomenon of societal disintegration.

Although the frustration of any and all fundamental needs, experienced at both individual and group levels, can potentially trigger this process, the loss of significanceFootnote 3 in particular emerges as a key factor (see Jaśko et al., 2020). Consistent with the 3 N theoretical framework proposed by Kruglanski et al. (2019), individuals and groups harbor a fundamental need to feel respected, recognized and valued. Hence, they are highly sensitive to any experience of diminished significance stemming from relative deprivation, humiliation, rejection, unfair treatment, failure, loss of social standing, and other related factors. In essence, any form of disadvantage encountered at the personal or group membership level can intensify individuals’ and groups’ motivation to grapple with factors perceived as serious threats, often compelling them to search for or develop beliefs that satisfy these needs (in the form of new narratives), and establish or engage with communities comprising individuals who share this perceived experience of diminished significance (networks, micro-identities).

Extending beyond its roots in marginalized narratives, the concept of micro-identities reveals its versatility, contributing valuable perspectives to a broader societal canvas. In a study conducted by Hochschild (2016) involving Trump supporters and Tea Party members, whose average income was slightly above the median, it was shown that many of these individuals had previously concealed their true feelings, mainly to align with societal norms of political correctness, as they saw it (Hochschild, 1979; 2012). This behavioral pattern is widespread, as individuals frequently align with societal and emotional norms, sometimes suppressing their authentic emotions. These emotional norms are often shaped by the expectations prevailing within their social or professional circles, commonly termed “feeling rules”, while the conformity to these rules is a type of “emotional labor” (Hochschild, 1992). Feeling rules are unwritten social norms that dictate how individuals should feel and express their emotions in accordance with societal and cultural expectations, and the efforts made to adhere to these rules often leads individuals to suppress their unmet desires, fearing being labeled as racist, homophobic, or sexist by society at large. Joining groups like the Tea Party provides an avenue for these individuals to connect with like-minded people and to express feelings and frustrations that societal norms discourage. As Hochschild notes, “their sense of being invisible and forgotten was the foundation of Trump’s appeal” (2016, p. 683). Similarly, in the United Kingdom, the sense of diminished control and significance drove many voters to endorse Brexit. Feeling unseen and overlooked, and experiencing a loss of control (as revealed by the British Election Study, 2015), they elected to embrace patriotism and anti-immigrant sentiments as a means of reclaiming a sense of worth.

In this way, micro-identities help individuals navigate their suppressed feelings, providing a platform for them to express themselves and connect with others who share similar sentiments. This phenomenon underscores the profound impact of ‘feeling rules’ and emotional labor on people’s choices and affiliations, and how these factors can contribute to larger social and political movements.

Moreover, a network of like-minded others validates and reinforces these narratives by forming a consensus regarding their content. This network, in addition, bolsters individuals’ behavior through social approval, subsequently elevating their status and acceptance, thereby enhancing their overall significance. It is essential to note that perceived threats to fundamental needs and values may or may not have an actual concrete basis in reality. Nonetheless, these feelings, baseless or not, can still generate a sense of community among those who share similar emotional experiences. This has been found to be the case among individuals identifying with ethnic majority experiencing unease, loss and insecurity in a rapidly changing world, and seeking refuge in the private sphere of a “home” characterized by exclusivity, particularity, and distinctiveness (Duyvendak, 2011). As mentioned earlier, this holds particular relevance not only for members of minority groups, who often perceive themselves as disadvantaged (Fox & Warber, 2015), but also for other groups, such as white men, who may feel threatened by societal changes. For instance, a cross-sectional study examining the first and second generation of Muslim immigrants in the US provided support for this thesis by demonstrating a positive relationship between marginalization and the loss of significance (i.e., low self-worth), which, in turn, positively predicted support for (1) radical interpretations of Islam and (2) fundamentalist groups (Lyons-Padilla et al., 2015).

A substantial body of evidence indicates that individuals, upon adopting a selected ideological narrative that offers the potential to reconstruct their sense of significance, security, and other related needs, are likely to be motivated to seek out others sharing the same beliefs and out-groups (Berger, 2018). Furthermore, shared perceptions of threatened needs, regardless of their accuracy, provide the conditions for individuals’ sense of identity to be compromised. This, in turn, promotes the development of solidarity within an existing group, even if it may have previously been of minor importance and negligible in terms of size. These shared perceptions can also contribute to the expansion of these groups, or even serve as catalysts for the emergence of entirely new ones. Such groups typically coalesce around religious and socio-political views, with a greater tendency to lean towards radical ideologies over liberal ones, even if initially these radical views had not necessarily been fully crystallized.

Subsequently, the process of societal disintegration can unfold as a result of the development of these various micro-identities, each marked by its own unique identity, strong intragroup connections, the construction of its own epistemic reality, and unwavering internal support for its ideology and actions (Belanger et al., 2014; Kruglanski et al., 2021). Importantly, the aforementioned groups, despite being characterized by their distinct identities and intragroup connections, are not necessarily small in size. Instead, they can exist as numerical minorities, relatively speaking, within their broader social context. Interestingly, many of the dynamics outlined here find considerable support in social identity theory (e.g., Huddy, 2001).

What are the reasons for regarding this process as inherently hazardous? Robust research demonstrates that individuals, when confronted with the thwarting of fundamental needs such as significance, certainty, and freedom, frequently cultivate a desire to hold accountable and punish those responsible (or those perceived as responsible) for their distress (Friedland, 1992). While the use of violence is generally proscribed and socially condemned, it becomes permissible when framed within an ideological context, as it provides moral justifications for its deployment against particular out-groups (Berger, 2018; Kruglanski et al., 2019). This implies that ideological narratives serve two vital functions. Firstly, ideologies operate as shared belief systems prescribing behaviors deemed necessary for fulfilling one’s needs (such as the attainment of personal significance), often linked to violence against perceived adversaries from ethnic, religious or social outgroups. Secondly, these ideological narratives furnish moral justifications so as to render the use of violence against outgroup members acceptable, or even commendable.

Returning to the subject of social media, it is clear that the process of developing micro-identities can occur independently of social media usage. Still, it is imperative to recognize that social media platforms possess the potential to enhance, turbocharge, and expedite the entire process (see Cinelli et al., 2021; Gaudette et al., 2021). This amplification fuels an ongoing social process that disrupts diverse societies by consolidating an ever-expanding array of issues into a single, widening social and cultural chasm. To illustrate this, our theoretical model is presented in Fig. 1, depicting a schematic representation of theoretical functional relationships amenable to testing through a research program.

This whole phenomenon can be largely attributed to the interplay between individuals’ motivation and cognitive biases, processes of social influence, and their engagement with social media, contributing to the formation of virtual micro-identities, and the construction of parallel yet divergent social realities which lack cohesiveness with the broader community (Higgins et al., 2021; Strömbäck, 2015; Törnberg, 2022). So, while it is true that social media usage can supply short-term fulfillment of individuals’ fundamental needs for security, belonginess, freedom, and significance (Chen et al., 2015), in the long term, it may also give rise to serious deficiencies (Kozyreva et al., 2020).

To complicate matters, media usage serves multiple purposes, functioning not only as a means for individuals to satisfy their frustrated needs, but also as a potential influencer of the need frustration–satisfaction process (Slater, 2015). A case in point is observed in online networking, which grants various groups, institutions, and companies a favorable strategic position by enabling the surveillance and data-mining of selected groups of citizens, thereby allowing them to exercise control over various aspects of human life. Additionally, personal information shared on digital platforms may also be publicly and permanently displayed, potentially leading to victimization or social exclusion of individuals and groups. The prevalence of selective self-presentation is rampant on social media, and can induce negative social comparisons related to one’s accomplishments, abilities, or appearance (Vogel et al., 2014). Therefore, over the long term, the use of social media may contribute to the perception, among some, that their fundamental needs are under threat, needs such as their personal security and certainty, their sense of freedom, and/or to their sense of significance, i.e., a basic desire to achieve a sense of respect (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

The experience of having one’s needs for security, freedom and significance frustrated, whether it be due to external conditions or media usage, or bothFootnote 4, has the potential to trigger a range of extreme in-group social influence and epistemic processes, manifested in ideological narratives. These processes involve motivational and cognitive processes such as (dis)confirmation bias, closed-mindedness, reluctance to accept available knowledge or evidence, and the polarization of beliefs, emotions, and action tendencies (Strömbäck, Wikforss et al., 2022). This can contribute to the formation of digital propaganda feedback loops, the widespread dissemination of fake news and disinformation (Benkler et al., 2018), the validation of extreme or ill-informed beliefs, and the radicalization commonly seen within certain minority groups susceptible to such influences (Berger, 2018). Notably, this tendency is further exacerbated when individuals eschew traditional and non-partisan mainstream news media outlets.

Concerning the ideological narratives circulating within and between these groups, we must acknowledge that these are not autonomous entities floating in a social vacuum; they necessitate validation and acceptance within and by their corresponding social networks. Individuals thus actively seek out social networks aligned with and endorsing their ideology, valuing actions which contribute to the group’s objectives. It seems plausible that a shared perception of threats to one’s fundamental human needs would be conducive to strengthening the existing social bonds in a group, or facilitating the development of groups, even if they were previously insignificant in size. This sense of threat can even lead to the inception of entirely new groups, based on religion, political and/or social convictions. Conversely, in the absence of such social contact, individuals may browse and graze on the “free market of ideas”, empowered by the widespread digitalization of information, allowing them to choose or “refine” the appropriate ideological, religious, and cultural narrative for themselves. Moreover, individuals may be susceptible to persuasion by their social network via digital tools, especially if they lack firm convictions in their own beliefs.

Practical implications

Are we in a position to proactively address the identified challenges? Our review yields several recommendations. One proposed approach, as articulated by Lewandowsky & Pomerantsev, 2022, involves the pursuit of a “better Internet” grounded in democratic principles. This would entail enabling users to gain an improved understanding of how their data is utilized, especially during electoral processes. The authors advocate for heightened online transparency and user control while preserving anonymity. In addition, they propose endowing users with the right to discern whether their interactions involve genuine individuals or political campaigns. Achieving this necessitates more stringent controls on data brokers, enhanced oversight of tech companies’ social experiments, and greater algorithmic transparency, including explanations for any adjustments being instituted. Regulatory authority is advocated to monitor efforts combating discriminatory practices. It is crucial, however, to recognize that, as delineated earlier, the Internet acts as a facilitating environment rather than the root cause of micro-identity emergence. Consequently, regulations for the Internet should be viewed as supplementary measures addressing symptoms of social fragmentation rather than silver bullets aimed at the underlying causes.

Alternatively, as Fukuyama (2019) suggests, exerting influence over a narrative that is deemed to be advantageous and universally applicable to diverse communities within a country, primarily for practical reasons rather than ideological considerations, stands a viable strategy. This type of narrative, representing the lowest common denominator for audiences/recipients of varied cultural and social identities with differing political views, should focus on an inclusive sense of national and civic identity. Communication at various levels should uphold this narrative for the successful maintenance of contemporary political and social order. Key reasons for doing this include ensuring physical security in societies facing the atrophy of social structures, fostering a quality of governing that prioritizes public services over divisive ideological politics, promoting a wide radius of trust facilitating economic and political participation, and constructing robust social safety nets to mitigate economic inequalities. Building such a basic and widely promoted narrative around national-civic identity makes liberal and inclusive democracy itself possible (Fukuyama, 2019) and constitutes a fundamental basis for a pluralistic society, without which further measures would be challenging or even impossible to implement (Peters & Witschge, 2015). The more detailed structure of such a narrative would vary greatly depending on the cultural conditions of each country, differing in the United States, in West Europe, in Central-Eastern Europe, and in the Global South (Heller, 2022).

An illustration of such a narrative can be found in the concept of South Africa’s Rainbow Nation (Baines, 1998), a term coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and later popularized by Nelson Mandela, which envisions a nation with diverse racial and cultural backgrounds coexisting harmoniously after apartheid. Similarly, the EU narrative emphasizes the idea of European citizens conjoined in a union that transcends national borders, promoting a shared European identity while respecting member state diversity. Another example is the phenomenon of Solidarność, a mass democratic social movement in communist Poland, which united various ideological groups across society under the banner of freedom, equality, solidarity, truth, patriotism and dignity (Bakuniak & Nowak, 1987). It played a key role in ending communism in Poland and Eastern Europe. This narrative approach was also successful in the 2023 parliamentary elections in Poland, where the Democratic Opposition, consisting of three party blocs, ranging from the left to the moderate center-right, promoted an inclusive sense of national and civic identity, both directly during election meetings and extensively on social media, thereby effectively contributing to a decisive election victory (Zerka, 2023).

Still, it would behoove us to recognize the limitations of singular efforts—be they individual, social, or political—since such endeavors, in and of themselves, cannot alone effectively counteract the process of societal disintegration if people’s fundamental needs languish in neglect. Thus, it is imperative to instill a sense of importance, significance, and value, both in the digital realm and in the physical world, for individuals who experience exclusionary or contemptuous treatment (whether actual or perceived). Additionally, it is essential to establish a sense of both actual and symbolic safety for those who feel threatened and actively promote an inclusive narrative in the political sphere, which can effectively deter radical content dissemination on social media. Achieving these objectives requires a thorough consideration of the values and identities of individuals and groups in the political process, as well as ensuring citizen participation in decision-making and policy development.

Introducing a proactive stance, Kruglanski and colleagues (2018) put forth actionable strategies for intervening in the three elements of the 3 N model. The first of these involves the restoration of motivational balance in vulnerable individuals and groups. Evidence suggests that we can steer individuals away from radical movements by addressing the motivational imbalance that drove them towards extremism in the first place. This can be accomplished by offering alternatives for personal meaning, as well as by addressing certain life dimensions such as security, job opportunities and emotional ties. Secondly, promoting ideological disillusionment based on evidence that radicals and/or terrorists often abandon extremism when they become disillusioned with their ideological narrative, specifically the moral values that legitimize violence. Hence, generating dissonance between certain violent schemas and alternative values can reduce legitimation of violence and/or promote breaking up the microgroup itself. Thirdly, endorsing alternative social networks that are inclusive and pro-social to hinder social fragmentation and encourage or strengthen ties within society. Importantly, these proposed interventions can be implemented at different levels (primary, secondary and tertiary prevention) to promote universal prevention or rehabilitation actions that aim to demobilize people and reintegrate them into society. The challenge for the future lies in understanding how the digital space can contribute to these processes, requiring collaboration between supranational institutions, states, and large technology companies to legislate and implement actions that foster safe spaces for the common good.

Future directions

While research on the role of digital media use in social transformations involving the creation of micro-identities has yielded substantial insights, it is encumbered by several limitations. Firstly, a notable proportion of studies reviewed here often rely on convenience samples, which may not faithfully represent the broader population. Consequently, the generalizability of findings is constrained, necessitating the inclusion of more diverse samples to attain a comprehensive grasp of (micro)group identity.

Furthermore, micro-identity and media usage are markedly contingent on various factors, including cultural, societal, and temporal elements. The majority of studies fixate on specific contexts, usually the US or Western Europe, confining the applicability of their findings. Hence, a more comprehensive examination across diverse social and cultural contexts is warranted. The analyses will be more generalizable if studies in other regions such as in Central-East Europe or in the Global South are conducted. Similarly, a predilection for investigating mainstream or readily accessible online communities is discernible in many studies, resulting in a neglect of the experiences and dynamics of underrepresented or marginalized groups. Thus, future research should prioritize inclusivity and representation of a broader spectrum of communities.

Presently, a sizeable portion of the research on media usage, micro-identity formation or social disintegration are mostly correlational in nature. While these associations provide valuable insights, ascertaining causality and dynamicity remains a daunting task. In order to elucidate causal relationships, longitudinal or experimental investigations are needed. The paucity of research on the enduring effects of media usage on micro-identity is currently conspicuous. Investigating the development of these relationships over time is imperative for a more profound comprehension of the implicated dynamics.

The precise measurement of micro-identity and media usage can be tricky since self-report measures are susceptible to biases; this highlights the necessity for more objective, uniform and standardized measurements across studies to facilitate meaningful comparisons. In addition, research has predominantly concentrated on the adverse or potentially deleterious aspects of micro-identity and media usage; more attention should be given to the beneficial implications, such as the pivotal role of online communities in offering support and nurturing a sense of belonging. Lastly, the ever-evolving digital landscape poses a perennial challenge, making it arduous for research to keep pace with the latest platforms and technologies. Staying abreast of the most recent digital developments is indispensable for scrutinizing the influence of media usage on micro-identity.

In summary, it is worth bearing in mind that while research into the psychological and social processes underpinning micro-identity and media usage is making commendable progress, addressing these limitations is imperative for the attainment of a more comprehensive and accurate understanding of these complex phenomena.

Conclusion

At the micro level, modern political culture is marked by the fusion of a given individual’s opinion and what they perceive to be their singular, permanent, and authentic self (Alvarez, 2017; Fukuyama, 2019). This intricate process is outlined above. At the macro level, however, the process of emerging social media usage and its possible repercussions are intertwined with financial crises, international conflicts and internal tensions, in a way that co-creates and interprets the physical reality we experience. These dynamics empower various groups, increasingly autonomous and independent of state structures, to establish their own spheres of activity and interaction. As social disintegration continues, reflected in the pervasive omnipresence of the internet, we risk a deterioration in social trust, particularly in times of crisis, and especially when democratic institutions are perceived to be inefficient and/or pursuing their own or partisan interests, rather than working for the public good.

In the face of these conditions, the online environment opens the door to the formation of communities distinct from, and acting as alternatives to, the centralized State. This may ultimately constitute a leading cause of the atrophy of social structures, undermining the shared rules and norms that underpin society. Greater understanding of these phenomena may help in the creation of strategies to maintain harmonious and sustainable societies.

Notes

In our paper, we have used Durkheim’s notion of disintegration (Durkheim, 1973; see also Acevedo, 2005; Lukes, 1977), to describe the breakdown or fragmentation of social structures, values, norms, and institutions that are essential for the cohesion of a community or a larger society. The disintegration of society occurs when the cohesion and integration among individuals and groups deteriorate, leading to a state where self-interest prevails, and a sense of control and restraint is seemingly lost. The erosion of trust, cooperation, and a shared sense of purpose is the result. (e.g., Scheiring & King, 2023; Klitgaard & Fedderke, 1995). Manifestations of societal disintegration can be observed through the weakening of social norms and values, fragmentation of social groups, decline in institutional effectiveness, and the presence of economic disparities and inequality (Scheiring & King, 2023).

In this paper, the term social media and digital platform use refers to engagement with online platforms, websites, or applications that enable individuals, organizations, or communities to communicate, connect, share content, and interact in a digital environment (Brennen & Kreiss, 2016).

This perspective is not limited to a motivational analysis, as it resonates with similar views across various academic fields, i.e., political science (e.g., Fukuyama, 2019), economics (Case & Deaton, 2020) and philosophy (Sandel, 2020), shedding light on the interconnectedness between dignity, recognition, economic conditions, and social dynamics.

The sense of diminished significance is often rooted in socio-cultural and environmental factors, a condition that can be exacerbated by media usage. The intertwining of external conditions, such as economic instability, political unrest, or societal inequalities, with media exposure has the potential to amplify the perception of insignificance. For instance, economic downturns or political turmoil may engender heightened feelings of insecurity and disempowerment among individuals, making them more susceptible to media content that resonates with these emotional states. Social media, with its persuasive storytelling and capacity to shape narratives, can validate and consolidate these feelings.

References

Acevedo GA (2005) Turning anomie on its head: fatalism as Durkheim’s concealed and multidimensional alienation theory. Sociol Theor 23(1):75–85

Ali M, Sapiezynski P, Korolova A, Mislove A, Rieke A (2021) Ad Delivery Algorithms: The Hidden Arbiters of Political Messaging. In: Proceedings of the 14th ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining 13-21

Alvarez M (2017) “Cogito Zero Sum”, Baffler. https://thebaffler.com/the-poverty-of-theory/cogito-zero-sum-alvarez

Arguedas AR, Robertson CT, Fletcher R, Nielsen RK (2022) Echo chambers, filter bubbles, and polarisation: A literature review. Reuters Institutefor the Study of Journalism

Bail C (2021) Breaking the social media prism. How to make our platforms less polarizing. Princeton University Press

Baines G (1998) The Rainbow Nation? Identity and Nation Building in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Mots Pluriels 7:1–12

Bakuniak G, Nowak K (1987) The Creation of a Collective Identity in a Social Movement: The Case of ‘Solidarność’ in Poland. Theory and Society, p. 401–429

Barbera P (2020) “Social Media, Echo chambers, and political polarization.” In Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, edited by Nathaniel Persily and Joshua Tucker, 34-57. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Barnidge M, Peacock C, Kim B, Kim Y, Xenos MA (2023) Networks and selective avoidance: How social media network influence unfriending and other avoidance behaviors. Soc Sci Comput Review 41:1017–1038

Bélanger JJ et al. (2014) The psychology of martyrdom: making the ultimate sacrifice in the name of a cause. J Pers Soc Psychol 107(3):494

Benkler Y, Faris R, Roberts H (2018) Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bennett Lance W, Livingston S (2021) The Disinformation Age: Politics, Technology, and Disruptive Communication in the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Berger JM (2018) Extremism. MIT Press

Bor A, Petersen MB (2022) The Psychology of Online Political Hostility: A Comprehensive, Cross-National Test of the Mismatch Hypothesis. Am Pol Sci Rev 116(1):1-18

Brennen JS, Kreiss D (2016) Digitalization. Int Encyclopedia of Commun Theory Philos 1–11

British Election Study (2015) https://www.britishelectionstudy.com/bes-resources/2015-and-social-media-new-ibesdata-released-by-rachel-gibson-and-ros-southern/

Bruns A (2019) Filter bubble. Internet Policy Review 8. https://doi.org/10.14763/2019.4.1426

Campbell HA, Golan O (2011) Creating digital enclaves: Negotiation of the internet among bounded religious communities. Media, Cult Soc 33:709-724

Case A, Deaton A (2020) Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism. Princeton University Press

Castro L et al. (2022) Navigating high-choice European political information environments: A comparative analysis of news user profiles and political knowledge. Int J Press/Polit 27(4):827–859

Chen B, Vansteenkiste M, Beyers W, Boone L, Deci EL, Van der Kaap-Deeder J, Richard MR et al. (2015) Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motiv Emot 39:216–236

Cinelli M, De Francisci Morales G, Galeazzi A, Quattrociocchi W, De Domenico M (2021) The echo chamber effect on social media. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(no. 9):e2023301118

Dauksza J, Sepioło M (2022) Pamięć i hejt. Frontstory. Dostępne pod adresem: https://frontstory.pl/dezinformacja-ukraina-rosja-internet-media-spolecznosciowe-mowa-nienawisci/ [dostęp: 27.10. 2022]

Dieckhoff A, Jaffrelot C, Massicard E (2022) Contemporary Populists in Power. Palgrave Macmillan

Dow BJ et al. (2021) The COVID‐19 pandemic and the search for structure: Social media and conspiracy theories. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 15(no. 9):e12636

Durkheim E (1997) The Division of Labor in Society. New York: The Free Press. Originally published in 1893

Duyvendak JW (2011) The Politics of Home. Belonging and Nostalgia in Europe and the United States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Eatwell R, Goodwin M (2018) National Populism. The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, Penguin UK

Ecker UKH et al. (2022) The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction. Nat Rev Psychol 1(no. 1):13–29

Egelhofer JL, Boyer M, Lecheler S, Aaldering L (2022) Populist attitudes and politicians disinformation accusations: Effects on perceptions of media and politicians. J Commun. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqac031

Ekström AG, Niehorster DC, Olsson EJ (2022) Self-imposed filter bubbles: Selective attention and exposure in online search. Comput Hum Behav Rep 7:100226

Escobar-Viera CG et al. (2018) Passive and active social media use and depressive symptoms among United States adults. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 21(no. 7):437–443

Feldstein S (2019) How artificial intelligence systems could threaten democracy. The Conversation https://theconversation.com/how-artificial-intelligence-systems-could-threaten-democracy-109698?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=twitterbutton

Fierro, M (2018) The almohad revolution: politics and religion in the Islamic West during the twelfth-thirteenth centuries. Routledge

Figenschou TU, Ihlebaek KA (2019) Challenging journalistic authority. Media criticism in far-right alternative media. Journal Stud 20(no. 9):1221–1237

Firro T (2018) Wahhabism and the Rise of the House of Saud. Sussex Academic Press

Fiske ST (2018) Social beings: Core motives in social psychology. John Wiley & Sons

Fletcher R, Nielsen RK (2017) Are news audiences increasingly fragmented? A cross-national comparative analysis of cross-platform news audience fragmentation and duplication. J Commun 67(no. 4):476–498

Fox J, Warber KM (2015) Queer identity management and political self-expression on social networking sites: A co-cultural approach to the spiral of silence. J Commun 65(no. 1):79–100

Friedland N (1992) “Becoming a terrorist: social and individual antecedents.” In: Laura Howard (Ed.), Terrorism: Roots, Impact, Responses, 81-93. London: Praeger

Fukuyama F (1992) The End of History and the Last Man. Free Press, New York

Fukuyama F (2019) Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment. Picador Edition, New York

Gartenstein-Ross D, Zammit A, Chace-Donahue E, Urban M (2023) “Composite Violent Extremism: Conceptualizing Attackers Who Increasingly Challenge Traditional Categories of Terrorism.” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. p. 1-27

Gaudette T, Scrivens R, Davies G, Frank R (2021) “Upvoting extremism: Collective identity formation and the extreme right on Reddit.”. New Media Soc 23(no. 12):3491–3508

George E (2019) Digitalization of Society and Socio-political Issues 1: Digital, Communication, and Culture (Vol. 1 and 2). London, Wiley

Gerbaudo P, Falco CCDe, Giorgi G, Keeling S, Murolo A, Nunziata F (2023) “Angry Posts Mobilize: Emotional Communication and Online Mobilization in the Facebook Pages of Western European Right-Wing Populist Leaders.”. Social Media+ Society 9(no. 1):20563051231163327

Guess AM, Barberá P, Munzert S, Yang J (2021) The consequences of online partisan media. Proc Natl Acad Sci 118(14):e2013464118

Guinote A (2017) How power affects people: Activating, wanting, and goal seeking. Annu Rev Psychol 68:353–381

Hardin CD, Higgins ET (1996) “Shared reality: how social verification makes the subjective objective.” In: E. Tory Higgins and R. Michael Sorrentino (eds.), Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: The Interpersonal Context, Vol. 3, 28-84. New York, NY, Guilford Press

Heller PA (2022) Democracy in the Global South. Annu Rev Sociol 48:463–484

Higgins ET, Rossignac-Milon M, Echterhoff GS (2021) Shared Reality: From Sharing-Is-Believing to Merging Minds. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 30(no. 2):103–110

Hochschild AR(1979) Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure Am J Sociol 85(3):551–575

Hochschild AR (2016) The ecstatic edge of politics: Sociology and Donald Trump. Contemp Sociol 45.6:683–689

Hochschild JL (1992) “The Word American in Can: The Amibiguous Promise of the American Dream.”. Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 34:139

Hochschild AR (1979) Emotion work, feeling rules, and social structure. Am J Sociol 85(3):551–575

Hochschild AR (2012) The outsourced self: What happens when we pay others to live our lives for us. Metropolitan Books

Holt K, Ustad Figenschou T, Frischlich L (2019) Key dimensions of alternative news media. Digit Journal 7(no. 7):860–869

Hornsey MJ (2008) Social identity theory and self‐categorization theory: A historical review. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2:204–222

Huddy L (2001) From social to political identity: A critical examination of social identity theory. Polit Psychol 22(no. 1):127–156

Humprecht E, Esser F, Van Aelst P (2020) Resilience to online disinformation: A framework for cross-national comparative research. Int J Press/Polit 25.3:493–516

Imperato C, Schneider BH, Caricati L, Amichai-Hamburger Y, Mancini T (2021) Allport meets internet: A meta-analytical investigation of online intergroup contact and prejudice reduction. Int J Intercult Relat 81:131–141

Iyengar S, Lelkes Y, Levendusky M, Malhotra N, Westwood SJ (2019) The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu Rev Polit Sci 22:129–146

Jamieson KH, Cappella JN (2008) Echo chamber. Rush Limbaugh and the conservative media establishment. Oxford University Press

Jasko K, Webber D, Kruglanski AW, Gelfand M, Taufiqurrohman M, Hettiarachchi M, Gunaratna R (2020) Social context moderates the effects of quest for significance on violent extremism. J Personal Soc Psychol 118(6):1165

Jennings MK, Zeitner B (2003) Internet use and civic engagement: A longitudinal analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly 67

Keyes, CF (2019) Thailand: Buddhist Kingdom as Modern Nation-State. Routledge

Klitgaard R, Fedderke J (1995) Social integration and disintegration: An exploratory analysis of cross-country data. World Dev 23(no. 3):357–369

Kossowska M, Czarnek G, Szumowska E, Szwed P (2022) Striving for Certainty: Epistemic Motivations and (Un) Biased Cognition. In: Knowledge Resistance in High-Choice Information Environments. Routledge, London, p 207–221

Kozyreva A, Lewandowsky S, Hertwig R (2020) Citizens versus the internet: Confronting digital challenges with cognitive tools. Psychol Sc Public Interest 21(no. 3):103–156

Kruglanski A, Jasko K, Webber D, Chernikova M, Molinario E (2018) The making of violent extremists. Rev Gen Psychol 22:107–120

Kruglanski AW et al. (2021) On the psychology of extremism: How motivational imbalance breeds intemperance. Psychol Rev 128.2:264

Kruglanski AW, Bélanger JJ, Gunaratna R (2019) The three pillars of radicalization: Needs, narratives and networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Latikka R, Koivula A, Oksa R, Savela N, Oksanen A (2022) “Loneliness and psychological distress before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: Relationships with social media identity bubbles.”. Soc Sci Med 293:114674

Leiser M (2019) “Regulating computational propaganda: Lessons from international law. Camb Int Law J 8(no. 2):218–240. https://doi.org/10.4337/cilj.2019.02.03

Lewandowsky S, Pomerantsev P (2022) Technology and Democracy: A Paradox Wrapped in a Contradiction Inside an Irony. Memory Mind Media 1:e5

Lewandowsky S, Wolfgang GK, Stritzke AM, Freund KO, Krueger JI (2013) Misinformation, disinformation, and violent conflict: from Iraq and the war on terror to future threats to peace. Am Psychol 68:487–501

Lewandowsky S, et al. (2020) Technology and Democracy: Understanding the influence of online technologies on political behaviour and decision-making. EUR 30422 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. ISBN 978-92-76-24088-4. https://doi.org/10.2760/709177

Lewandowsky S, Robertson RE, DiResta R (2023) “Challenges in Understanding Human-Algorithm Entanglement During Online Information Consumption.” Perspectives on Psychological Science. 17456916231180809

Lindgren S (2021) Digital Media and Society. New York, Sage

Lorenz-Spreen P, Oswald L, Lewandowsky S et al. (2023) A systematic review of worldwide causal and correlational evidence on digital media and democracy. Nat Hum Behav 7:74–101. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01460-1

Loxton M, Truskett R, Scarf B, Sindone L, Baldry G, Zhao Y (2020) Consumer behaviour during crises: Preliminary research on how coronavirus has manifested consumer panic buying, herd mentality, changing discretionary spending and the role of the media in influencing behaviour. J Risk Financ Manag 13(no. 8):166

Lüders A, Dinkelberg A, Quayle M (2022) Becoming ‘Us’ in Digital Spaces: How Online Users Creatively and Strategically Exploit Social Media Affordances to Build up Social Identity. Acta Psychol 228:103643

Lukes S (1977) The Critical Theory Trip. Polit Stud 25(3):408–412

Lyons-Padilla S, Gelfand MJ, Mirahmadi H, Farooq M, van Egmond M (2015) Belonging nowhere: Marginalization & radicalization risk among Muslim immigrants.”. Behav Sci Policy 1:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1353/bsp.2015.0019

Marmarosh CL, Forsyth DR, Strauss B, Burlingame GM (2020) The psychology of the COVID-19 pandemic: A group-level perspective. Group Dyn 24(no. 3):122

McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, Cook JM (2001) Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu Rev Sociol 27:415–444

Mearsheimer J (2018) Great Delusion: Liberal Dreams and International Realities. Yale University Press

Mihailidis P, Viotty S (2017) Spreadable spectacle in digital culture: civic expression, fake news, and the role of media literacies in post-fact society. Am Behav Sci 61:441–454

Mounk Y, Foa RS (2017) The Signs of Deconsolidation. J Democr 28:1

Muller C (2020) “The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law.” Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Norris P, Inglehart R (2019) Cultural backlash. Trump, Brexit and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press

Pariser Eli (2011) The Filter Bubble: What The Internet Is Hiding From You. Penguin, London

Persily N, Tucker JA (2020) Social Media and Democracy: The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform. Cambridge University Press

Peters C, Witschge T (2015) From Grand Narratives of Democracy to Small Expectations of Participation. Journal Pract 9:9–34

Praet AM, Guess JA, Tucker R, Bonneau J, Nagler J (2022) What’s Not to Like? Facebook Page Likes Reveal Limited Polarization in Lifestyle Preferences. Polit Commun 39:311–338

Pratto F, Sidanius J, Levin S (2006) Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward. Eur Rev Soc Psychol 17.1:271–320

Prensky M (2001) “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants.” On the Horizon 9, MCB University Press

Rashid Jihad A (2003) The Rise of Militant Islam in Central Asia. Yale University Press

Salem P, Ross H (2022) Escaping the Conflict Trap: Toward Ending Civil War in the Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing

Sandel M (2020) “The tyranny of merit: What’s become of the common good?” Allen Lane

Scharfbillig M, Smillie L, Mair D, Sienkiewicz M, Keimer J, Pinho Dos Santos R, Vinagreiro Alves H, Vecchione E, Scheunemann L (2021) Values and Identities - a policymaker’s guide, EUR 30800 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2760/022780

Scheiring G, King L (2023) Deindustrialization, social disintegration, and health: a neoclassical sociological approach. Theor Soc 52:145–178

Slater M (2015) Reinforcing Spirals Model: Conceptualizing the Relationship Between Media Content Exposure and the Development and Maintenance of Attitudes. Media Psychol 18:370–395

Strauß N, Alonso-Muñoz L, Gil de Zuniga H (2020) Bursting the filter bubble: the mediating effect of discussion frequency on network heterogeneity. Online Inform Rev 44(no. 6):1161–1181

Strömbäck J (2015) “Future Media Environments, Democracy and Social Cohesion.” In: Digital Opportunities, 1st ed., edited by Digitaliseringskommissionen, 97-122. Stockholm, Digitaliseringskommissionen

Strömbäck J, Boomgaarden H, Broda E, et al. (2022) “From low-choice to high-choice media environments: Implications for knowledge resistance.” In Knowledge Resistance in High-Choice Information Environments, edited by Jesper Strömbäck, Åsa Wikforss, Karin Glüer, Tommy Lindholm, and Henrik Oscarsson, 49-68. Routledge

Strömbäck J, Wikforss Å, Glüer K, Lindholm T, Oscarsson H (2022) Knowledge Resistance in High-Choice Information Environments. Routledge

Sunstein CR (2007) Republic.com 2.0. Princeton University Press,

Svolik MW (2019) “Polarization versus Democracy.” J Democr. Accessed January 21, 2022. https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/articles/polarization-versus-democracy/

Tajfel H et al. (1979) An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organ Identity 56.65:9780203505984-16

Terren L, Borge-Bravo R (2021) Echo chambers on social media: A systematic review of the literature. Rev Commun Res 9:99–118

Theocharis Y, Cardenal A, Jin S, Aalberg T, Hopmann DN, Strömbäck J, Castro L, Esser F, Van Aelst P, de Vreese C, Corbu N, Koc-Michalska K, Matthes J, Schemer C, Sheafer T, Splendore S, Stanyer J, Stepinska A, Stetka V (2023) Does the platform matter? Social media and COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs in 176 countries.”. New Media Soc 25(no 12):3412–3437

Thorisdottir IE, Sigurvinsdottir R, Asgeirsdottir BB, Allegrante JP, Sigfusdottir ID (2019) Active and passive social media use and symptoms of anxiety and depressed mood among Icelandic adolescents. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 22(no. 8):535–542

Tönnies F (2019) Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft. 1880-1935., edited by Bettina Clausen and Dieter Haselbach. De Gruyter, Berlin/Boston, (originally published in 1887)

Törnberg P (2022) How Digital Media Drive Affective Polarization Through Partisan Sorting. Proc Natl Acad Sci 119(no. 42):e2207159119

Tucker J, Theocharis Y, Roberts M, Barberá P (2017) From liberation to turmoil: Social media and democracy. J Democr 28:46–59

Venturini T (2022) Online Conspiracy Theories, Digital Platforms and Secondary Orality: Toward a Sociology of Online Monsters. Theor Cult Soc 39(no. 5):61–80

Del Vicario M et al. (2016) Echo chambers: Emotional contagion and group polarization on Facebook. Sci Rep 6(no. 1):37825

Vogel EA, Rose JP, Roberts LR, Eckles K (2014) Social comparison, social media, and self-esteem. Psychol Popr Media Cult 3(no. 4):206–222

Webster JG (2014) The marketplace of attention. How audiences take shape in a digital age. MIT Press

West EA, Iyengar S (2022) Partisanship as a social identity: Implications for polarization. Polit Behav 44(no. 2):807–838

Wu T (2017) The Attention Merchants. London, UK, Atlantic Books

Yang Z, Luo X, Jia H (2021) Is it all a conspiracy? Conspiracy theories and people’s attitude to COVID-19 vaccination. Vaccines 9(no. 10):1051

Yarchi M, Baden C, Kligler-Vilenchik N (2021) Political Polarization on the Digital Sphere: A Cross-platform, Over-time Analysis of Interactional, Positional, and Affective Polarization on Social Media. Polit Commun 38(no. 1-2):98–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2020.1785067

Zerka P (2023) Message in a ballot: What Poland’s election means for Europe. European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/article/message-in-a-ballot-what-polands-election-means-for-europe/

Acknowledgements

This publication is supported by: NCN Poland; FORTE: Swedish Research Council for Health, Working life and Welfare; the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, Germany; Cobierno de Espania, Ministerio de Ciencia eInnovacion Spain; UKRI Economic and Social Research Council, and UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council. The UK, under the CHANSE ERA-NET Co-fund programme, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme, under Grant Agreement no. 101004509.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors’ contributions are as follows: MK, PK, ASC developed the rationale for the paper; MK, PK and ASC wrote the manuscript, AG, UK, MM, JS critically commented the first draft, all authors critically read the manuscript and provided comments that helped refine the final version. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants not applicable; however, the paper is the result of a project that obtained ethical approval for the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kossowska, M., Kłodkowski, P., Siewierska-Chmaj, A. et al. Internet-based micro-identities as a driver of societal disintegration. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 955 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02441-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02441-z