Abstract

Blind and deaf individuals comprise large populations that often experience health disparities, with those from marginalized gender, racial, ethnic and low-socioeconomic communities commonly experiencing compounded health inequities. Including these populations in precision medicine research is critical for scientific benefits to accrue to them. We assessed representation of blind and deaf people in the All of Us Research Program (AoURP) 2018–2023 cohort of participants who provided electronic health records and compared it with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2018 national estimates by key demographic characteristics and intersections thereof. Blind and deaf AoURP participants are considerably underrepresented in the cohort, especially among working-age adults (younger than age 65 years), as well as Asian and multi-racial participants. Analyses show compounded underrepresentation at the intersection of multiple marginalization (that is, racial or ethnic minoritized group, female sex, low education and low income), most substantively for working-age blind participants identifying as Black or African American female with education levels lower than high school (representing one-fifth of their national prevalence). Underrepresentation raises concerns about the generalizability of findings in studies that use these data and limited benefits for the already underserved blind and deaf populations.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

In line with the privacy standards set by the AoURP, data used for this study are available to approved researchers who register for access to the Researcher Workbench platform at https://workbench.researchallofus.org/login. This analysis was run on the AoURP Registered Tier Dataset version 6 production release R2022Q2R6. The CDC-NHIS data used for national representation are included in the code repository below and at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/nhis_2018_data_release.htm.

Code availability

The code written by study investigators is available in a GitHub repository at https://github.com/gitclv/blind_deaf_representation_AoURP_EHR.

References

Okoro, C. A., Hollis, N. D., Cyrus, A. C. & Griffin-Blake, S. Prevalence of disabilities and health care access by disability status and type among adults—United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 67, 882–887 (2018).

Krahn, G. L., Walker, D. K. & Correa-De-Araujo, R. Persons with disabilities as an unrecognized health disparity population. Am. J. Public Health 105, S198–S206 (2015).

Bialik, K. 7 Facts About Americans with Disabilities (Pew Research Center, 2017); https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/07/27/7-facts-about-americans-with-disabilities/

Goyat, R., Vyas, A. & Sambamoorthi, U. Racial/ethnic disparities in disability prevalence. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 3, 635–645 (2016).

Maroto, M., Pettinicchio, D. & Patterson, A. C. Hierarchies of categorical disadvantage: economic insecurity at the intersection of disability, gender, and race. Gend. Soc. 33, 64–93 (2019).

Yee, S. et al. Compounded Disparities: Health Equity at the Intersection of Disability, Race, and Ethnicity (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018); https://dredf.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Compounded-Disparities-Intersection-of-Disabilities-Race-and-Ethnicity.pdf

Ramirez, A. H., Gebo, K. A. & Harris, P. A. Progress with the All of Us Research Program: opening access for researchers. JAMA 325, 2441–2442 (2021).

2018 National Health Interview Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019); https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/1997-2018.htm

Varma, R. et al. Visual impairment and blindness in adults in the United States: demographic and geographic variations from 2015 to 2050. JAMA Ophthalmol. 134, 802–809 (2016).

Goman, A. M., Reed, N. S. & Lin, F. R. Addressing estimated hearing loss in adults in 2060. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 143, 733–734 (2017).

Barnett, S., McKee, M., Smith, S. R. & Pearson, T. A. Deaf sign language users, health inequities, and public health: opportunity for social justice. Prev. Chronic Dis. 8, A45 (2011).

Crews, J. E., Chou, C.-F., Sekar, S. & Saaddine, J. B. The prevalence of chronic conditions and poor health among people with and without vision impairment, aged ≥65 years, 2010–2014. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 182, 18–30 (2017).

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice; Committee on Public Health Approaches to Reduce Vision Impairment and Promote Eye Health. Making Eye Health a Population Health Imperative: Vision for Tomorrow (National Academies Press, 2016); https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27656731/

Lor, M., Thao, S. & Misurelli, S. M. Review of hearing loss among racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. West. J. Nurs. Res. 43, 859–876 (2021).

Ulldemolins, A. R., Lansingh, V. C., Valencia, L. G., Carter, M. J. & Eckert, K. A. Social inequalities in blindness and visual impairment: a review of social determinants. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 60, 368–375 (2012).

Sabatello, M., Chen, Y., Zhang, Y. & Appelbaum, P. S. Disability inclusion in precision medicine research: a first national survey. Genet. Med. 21, 2319–2327 (2019).

Flaxman, A. D. et al. Prevalence of visual acuity loss or blindness in the US: a Bayesian meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 139, 717–723 (2021).

Mitchell, R. E. How many deaf people are there in the United States? Estimates from the survey of income and program participation. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 11, 112–119 (2006).

Chan, T., Friedman, D. S., Bradley, C. & Massof, R. Estimates of incidence and prevalence of visual impairment, low vision, and blindness in the United States. JAMA Ophthalmol. 136, 12–19 (2018).

Goman, A. M. & Lin, F. R. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 106, 1820–1822 (2016).

DeCormier Plosky, W. et al. Excluding people with disabilities from clinical research: eligibility criteria lack clarity and justification. Health Aff. (Millwood) 41, 1423–1432 (2022).

Young, J. L. & Cho, M. K. The invisibility of Asian Americans in COVID-19 data, reporting, and relief. Am. J. Bioeth. 21, 100–102 (2021).

Peavey, J. J. et al. Impact of socioeconomic disadvantage and diabetic retinopathy severity on poor ophthalmic follow-up in a rural Vermont and New York population. Clin. Ophthalmol. 14, 2397–2403 (2020).

Shearer, A. E., Hildebrand, M. S., Schaefer, A. M. & Smith, R. J. GeneReviews® (Univ. Washington, 2023).

Coday, M. P., Warner, M. A., Jahrling, K. V. & Rubin, P. A. D. Acquired monocular vision: functional consequences from the patient’s perspective. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 18, 56–63 (2002).

Krebs, J., Roehm, D., Wilbur, R. B. & Malaia, E. A. Age of sign language acquisition has lifelong effect on syntactic preferences in sign language users. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 45, 397–408 (2021).

Schniedewind, E., Lindsay, R. P. & Snow, S. Comparison of access to primary care medical and dental appointments between simulated patients who were deaf and patients who could hear. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e2032207 (2021).

Lagu, T. et al. ‘I am not the doctor for you’: physicians’ attitudes about caring for people with disabilities. Health Aff. (Millwood) 41, 1387–1395 (2022).

Gianfrancesco, M. A. & Goldstein, N. D. A narrative review on the validity of electronic health record-based research in epidemiology. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 21, 234 (2021).

Chute, C. G. Coding patient information, reimbursement for care, and the ICD transition. AMA J. Ethics 15, 596–599 (2013).

World Health Organization ICF Browser (World Health Organization, 2017); https://apps.who.int/classifications/icfbrowser/

Poverty Thresholds by Size of Family and Number of Children (United States Census Bureau, 2022); https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/income-poverty/historical-poverty-thresholds.html

Distribution of the Total Population by Federal Poverty Level (Above and Below 200% FPL) (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023); https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/population-up-to-200-fpl/?currentTimeframe=1&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Poverty Data Tables (United States Census Bureau, 2019); https://www.census.gov/topics/income-poverty/poverty/data/tables.2019.html

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Office of the Director (OD) grant R01HG010868 (M.S.) and Columbia University’s Precision Medicine: Ethics, Politics & Culture (M.S. and C.L.). We also thank T. Sun for brainstorming on the figures. Data for this manuscript were obtained through the All of Us Research Program’s Registered Tier Dataset version 6 production. The All of Us Research Program is supported by the NIH OD: Regional Medical Centers: 1 OT2 OD026549; 1 OT2 OD026554; 1 OT2 OD026557; 1 OT2 OD026556; 1 OT2 OD026550; 1 OT2 OD 026552; 1 OT2 OD026553; 1 OT2 OD026548; 1 OT2 OD026551; 1 OT2 OD026555; IAA: AOD 16037; Federally Qualified Health Centers: HHSN 263201600085U; Data and Research Center: 5 U2C OD023196; Biobank: 1 U24 OD023121; Participant Center: U24 OD023176; Participant Technology Systems Center: 1 U24 OD023163; Communications and Engagement: 3 OT2 OD023205; 3 OT2 OD023206; and Community Partners: 1 OT2 OD025277; 3 OT2 OD025315; 1 OT2 OD025337; 1 OT2 OD025276. In addition, we would like to acknowledge the contribution of the All of Us Research Program’s research participants. The All of Us Research Program would not be possible without the partnership of its participants. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The content of this work is solely that of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. We are grateful for insights from Howard Rosenblum, of the National Association of the Deaf, and Lou Ann Blake, of the National Federation of the Blind.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and design: M.S., C.L. and G.H. Acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data: C.L., J.H. and M.S. Drafting of the manuscript: C.L. and M.S. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: C.L., J.H., G.H. and M.S. Statistical analysis: C.L. Funding acquisition: M.S. Supervision: M.S.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.S. is a member of the institutional review board of the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Medicine thanks Isabelle Boisvert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jennifer Sargent, in collaboration with the Nature Medicine team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Cohort description.

Breakdown of full study population (AoURP EHR volunteers) into blind and deaf cohorts. See Supplemental Table 2 for the full list of SNOMED standard concept names and codes that determine cohort membership when found in participant EHR.

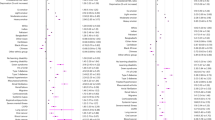

Extended Data Fig. 2 Prevalence gaps of blind participants at the intersection of sex, education, and household income (working-age, ≤65 years).

Prevalence comparison between AoURP and national estimates for blind participants in each intersectional group (top); Distances from parity by intersectional group (bottom).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Prevalence gaps of deaf participants at the intersection of sex, education, and household income (working-age, ≤65 years).

Prevalence comparison between AoURP and national estimates for deaf participants in each intersectional group (top); Distances from parity by intersectional group (bottom).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Prevalence gaps of blind participants at the intersection of sex, education, and race/ethnicity (working-age, ≤65 years).

Prevalence comparison between AoURP and national estimates for blind participants in each intersectional group (top); Distances from parity by intersectional group (bottom).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Prevalence gaps of deaf participants at the intersection of sex, education, and race/ethnicity (working-age, ≤65 years).

Prevalence comparison between AoURP and national estimates for deaf participants in each intersectional group (top); Distances from parity by intersectional group (bottom).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Prevalence gaps of deaf participants (working-age, ≤65 years) by intersectional race/ethnicity, sex, and education categories.

Prevalence gaps at three-level intersectionality for deaf participants: 1) race or ethnicity alone (top); 2) race or ethnicity and sex (middle); and 3) race or ethnicity, sex and education (bottom).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table 1

aAll Hispanic-identifying participants were grouped as ‘Hispanic’ (without listing race), with the other ethnic group comprising only non-Hispanic participants. The AoURP does not currently provide data about American Indian and Alaska Native participants. b‘Poor’ families are defined as those with incomes below the 2018 federal poverty threshold. ‘Near poor’ families have household incomes of 100% to less than 200% of the poverty threshold. ‘Not poor’ families have household incomes over 200% of the threshold. Thresholds are calculated using incomes ranging from $12,140 to $55,340 depending on household size.

Supplementary Table 2

Cohort and SNOMED standard concept name. (*) indicates bilateral.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lewis V, C., Huebner, J., Hripcsak, G. et al. Underrepresentation of blind and deaf participants in the All of Us Research Program. Nat Med 29, 2742–2747 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02607-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02607-x