Abstract

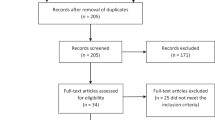

Demographically diverse surveys in the United States suggest that 10–15% of non-voluntarily circumcised American males wish that they had not been circumcised [1, 2]. Similar data are unavailable in other countries. An unknown proportion of circumcised males experience acute circumcision-related distress; some attempt to regain a sense of bodily integrity through non-surgical foreskin restoration. Their concerns are often ignored by health professionals. We conducted an in-depth investigation into foreskin restorers’ lived experiences. An online survey containing 49 qualitative and 10 demographic questions was developed to identify restorers’ motivations, successes, challenges, and experiences with health professionals. Targeted sampling was employed to reach this distinctive population. Invitations were disseminated to customers of commercial restoration devices, online restoration forums, device manufacturer websites, and via genital autonomy organizations. Over 2100 surveys were submitted by respondents from 60 countries. We report results from 1790 fully completed surveys. Adverse physical, sexual, emotional/psychological and self-esteem impacts attributed to circumcision had motivated participants to seek foreskin restoration. Most sought no professional help due to hopelessness, fear, or mistrust. Those who sought help encountered trivialization, dismissal, or ridicule. Most participants recommended restoration. Many professionals are unprepared to assist this population. Circumcision sufferers/foreskin restorers have largely been ill-served by medical and mental health professionals.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 8 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $32.38 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

27 July 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00741-1

Notes

A peer reviewer has asked us to elaborate, and we do so briefly here. While heterosexual males may be visually familiar with penile aesthetics through partially-mediated experiences (e.g., watching pornography; seeing male genitalia in changing rooms at some distance), gay/bi men likely have broader and/or less-mediated experiences with circumcised and intact penises in the context of intimate interpersonal encounters, allowing for multi-modal comparisons (i.e., via sight, touch, smell, taste and even sound). In addition, concerns around bodily autonomy may be of heightened significance for gay/bi men in relation to such matters as what may be done to one’s body–vis-à-vis threats of medical or psychological “conversion therapies”, arrest or imprisonment under sodomy laws, hate-motivated violence, and so on. As such, long-standing LGBTQ + concepts of body ownership and bodily autonomy may foster a deeper awareness, understanding, and/or sensitivity to issues that lie at the intersection of sexuality and human rights [20]. For further analysis, see Unabridged Supplementary Section “Gay/Bisexual men”.

Although numerous immediate and short-term complications have been documented [26, 27], there is no universally accepted definition among professionals of what constitutes a circumcision “complication”, especially in the un(der)-investigated long-term. Nevertheless, a systematic review concluded that neonatal penile circumcision complications are likely more common than is typically surmised [28]. Many complications are never recorded because they become evident only as the penis develops. An analysis of medicalized MGC found a complication rate of 4% and that adult complications are not greater than infant complications [29].

References

Earp B, Sardi L, Jellison W. False beliefs predict increased circumcision satisfaction in a sample of US American men. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20:945–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2017.1400104.

Moore P. Younger Americans less supportive of circumcision at birth. 2015. https://today.yougov.com/topics/society/articles-reports/2015/02/03/younger-americans-circumcision.

Doyle D. Ritual male circumcision: a brief history. J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 2005;35:279–85.

Gollaher D. Circumcision: a history of the world’s most controversial surgery. New York: Basic Books; 2000.

Glick L. Marked in your flesh: circumcision from ancient Judea to modern America. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Board of Trustees. American Medical Association. Definition of Surgery H-475.983. 2003. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/surgery?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-4317.xml.

Maeda J, Chari R, Elixhauser A. Circumcisions in U.S. community hospitals, 2009. In: HCUP Statistical Brief #126. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality;2012. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb126.pdf.

Zhang X, Shinde S, Kilmarx P, Chen R, Cox S, Warner L, et al. Trends in in-hospital newborn male circumcision: United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1167–8. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6034a4.htm.

Chapin G. Intact America. Don’t Ask. Don’t Sell®. 2022. https://intactamerica.org/dont-ask-dont-sell/.

Serody M. More than 5 million American men may want their foreskins back. Foregen/YouGov. 2021. https://www.foregen.org/commentarium-articles/yougov-survey-2021.

Hall R. Epispasm: circumcision in reverse. Bible Review. 1992:52–7. Available from: http://www.cirp.org/library/restoration/hall1/.

Penn J. Penile reform. Br J Plast Surg. 1963;16:287–8. http://www.cirp.org/library/restoration/penn1/.

Greer D, Mohl P, Sheley K. A technique for foreskin reconstruction and some preliminary results. J Sex Res. 1982;18:324–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3812166.

Goodwin W. Uncircumcision: a technique for plastic reconstruction of a prepuce after circumcision. J Urol. 1990;144:1203–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(17)39693-3.

Haseebuddin M, Brandes S. The prepuce: preservation and reconstruction. Curr Opin Urol. 2008;18:575–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/MOU.0b013e328311c9c2.

Bossio J, Pukall C. Attitude toward one’s circumcision status is more important than actual circumcision status for men’s body image and sexual functioning. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47:771–81. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-1064-8.

Uberoi M, Abdulcadir J, Ohl D, Santiago J, Rana G, Anderson J. Potentially under-recognized late-stage physical and psychosexual complications of non-therapeutic neonatal penile circumcision: a qualitative and quantitative analysis of self-reports from an online community forum. Int J Impot Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00619-8.

New foreskin. Coverage index: how much foreskin do you have? 2022. www.restoringforeskin.org/coverage-index/CI-chart.htm.

World population review. Circumcision rates by state 2022. https://worldpopulationreview.com/state-rankings/circumcision-rates-by-state.

Hammond T. A cut by any other name: a deep-dive interview with ethicist Brian Earp (Parts 1 & 2). Empty Closet. 2020. Available from: http://circumcisionharm.org/images-circharm.org/2020%20EC%20Earp%20interview%20Pt1&2%20(May-Jun).pdf

Ehrenreich N, Barr M. Intersex surgery, female genital cutting, and the selective condemnation of ‘cultural practices’. Harv Civ Rights-Civil Lib Law Rev. 2005;40:71–140.

Ziemińska R. The epistemic injustice expressed in “normalizing” surgery on children with intersex traits. Diametros. 2020;17:52–65. https://doi.org/10.33392/diam.1478.

Tortorella v Castro. Court of Appeal, Second District, Division 3, California. Case No. B184043. Decided: June 01, 2006 https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=8009703171466596993&q=Tortorella+v+Castro&hl=en&as_sdt=40000006.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Report of the task force on circumcision. Pediatrics. 1989;84:388–91.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Task force on circumcision. Technical report on male circumcision. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e756–85. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1990.

Fahmy MAB. Complications of male circumcision (ch 7–12). In: Fahmy MAB, editor. Complications of male circumcision. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017. p. 49–170.

Stanford Medicine. Complications of circumcision. Newborn Nursery/Professional Education. 2016. https://med.stanford.edu/newborns/professional-education/circumcision/complications.html. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

Iacob S, Feinn R, Sardi L. Systematic review of complications arising from male circumcision. BJUI Compass. 2022;3:99–123. https://doi.org/10.1002/bco2.123.

Shabanzadeh D, Clausen S, Maigaard K, Fode M. Male circumcision complications— a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Urology. 2021;152:25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.01.041.

Frisch M, Simonsen J. Cultural background, non-therapeutic circumcision and the risk of meatal stenosis and other urethral stricture disease: two nationwide register-based cohort studies in Denmark 1977–2013. Surgeon. 2018;16:107–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surge.2016.11.002.

Hammond T. A preliminary poll of men circumcised in infancy or childhood. BJU Int. 1999;83:85–92. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1085.x.

Hammond T, Carmack A. Long-term adverse outcomes from neonatal circumcision reported in a survey of 1008 men: an overview of health and human rights implications. Int J Hum Rights. 2017;21:189–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2016.1260007.

Tirana R, Othman D, Gad D, Elsadek M, Fahmy MAB. Pigmentary complications after non‑medical male circumcision. BMC Urol. 2022;22:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-022-00999-5.

Van Howe R. Incidence of meatal stenosis following neonatal circumcision in a primary care setting. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2006;45:49–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/000992280604500108.

Acimi S, Abderrahmane N, Debbous L, Bouziani N, Mansouri J, Acimi M, et al. Prevalence and causes of meatal stenosis in circumcised boys. J Pediatr Urol. 2022;18:89.e1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.10.008.

Dailey D. Sexual expression and ageing. In: Berghorn F, Schafer D, editors. The dynamics of aging: original essays on the processes and experiences of growing old. Boulder: Westview Press; 1981. p. 311–30.

Einstein G. From body to brain: considering the neurobiological effects of female genital cutting. Perspect Biol Med. 2008;51:84–97. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2008.0012.

Immerman RS, Mackey WC. A biocultural analysis of circumcision. Soc Biol. 1997;44:265–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.1997.9988953.

Immerman RS, Mackey WC. A proposed relationship between circumcision and neural reorganization. J Genet Psychol. 1998;159:367–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221329809596158.

Darby R, Svoboda JS. A rose by any other name? Rethinking the similarities and differences between male and female genital cutting. Med Anthropol Q. 2007;21:301–23. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.2007.21.3.301.

Bell K. Genital cutting and Western discourses on sexuality. Med Anthropol Q. 2005;19:125–48.

Johnsdotter S. Girls and boys as victims: asymmetries and dynamics in European public discourses on genital modifications in children. International seminar FGM/C: from medicine to critical anthropology. 2017. https://www.academia.edu/35343412/Girls_and_Boys_as_Victims_Asymmetries_and_dynamics_in_European_public_discourses_on_genital_modifications_in_children. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

Gruenbaum E, Earp BD, Shweder RA. Reconsidering the role of patriarchy in upholding female genital modifications: analysis of contemporary and pre-industrial societies. Int J Impot Res. 2022. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41443-022-00581-5.

Johnsdotter S. Discourses on sexual pleasure after genital modifications: the fallacy of genital determinism (a response to J. Steven Svoboda). Glob Discourse. 2013;3:256–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2013.805530.

Bollinger D, Van Howe R. Alexithymia and circumcision trauma: a preliminary investigation. Int J Men’s Health. 2011;10:184–95. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.1002.184.

Tye M, Sardi L. Psychological, psychosocial, and psychosexual aspects of penile circumcision. Int J Impot Res. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-022-00553-9.

Coates S. Can babies remember trauma? Symbolic forms of representation in traumatized infants. J Am Psychoanal Assoc. 2016;64:751–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065116659443.

Miani A, Di Bernardo G, Højgaard A, Earp B, Zak P, Landau A, et al. Neonatal male circumcision is associated with altered adult socio-affective processing. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05566.

Bollinger D, Chapin G. Childhood genital cutting as an adverse childhood experience. Intact Am. 2019. http://adversechildhoodexperiences.net/CGC_as_an_ACE.pdf.

Anonymous. Regrowing my foreskin: how I’m overcoming the trauma of infant circumcision. The Journal/Queen’s University. 2021. https://www.queensjournal.ca/story/2021-01-21/postscript/regrowing-my-foreskin/. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

Massie L. Rapid response: male circumcision and unexplained male adolescent suicide. Br Med J. 2010:340. https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/11/02/male-circumcision-and-unexplained-male-adolescent-suicide.

Morgan J. Gay man, who suffered from depression over his circumcision, kills himself. Gay Star News. 2016. https://www.gaystarnews.com/article/gay-man-suffered-depression-circumcision-kills/. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

Toureille C. Jewish man who endured a botched circumcision as a baby reveals it left him with years of pain and drove him to contemplate suicide. Daily Mail/UK. 2019. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-7261193/Man-admits-botched-circumcision-baby-led-consider-suicide.html. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

Watson L. Unspeakable mutilations: circumcised men speak out. Ashburton: Create Space Publishing; 2014.

Watson L, Golden T. Male circumcision grief: effective and ineffective therapeutic approaches. N Male Stud Int J. 2017;6:109–25. https://www.newmalestudies.com/OJS/index.php/nms/article/view/261/317.

Toubia N. Female genital mutilation and the responsibility of reproductive health professionals. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;46:127–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/0020-7292(94)90227-5.

Montgomery S. Controversy over circumcision persists. The Exponent. 2021. https://www.purdueexponent.org/city_state/article_b95b2cf7-c0ef-51f2-8308-fad024fb1380.html. Accessed 18 Dec 2021.

Wisdom T. Questioning circumcisionism: feminism, gender equity, and human rights. Righting Wrongs J Hum Rights. 2012;2:1–32.

Wisdom T. Constructing phallic beauty: foreskin restoration, genital cutting and circumcisionism. In: McNamara S, editor. (Re)Possessing beauty: politics, poetics, change. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press; 2014. p. 93–134.

Özer M, Timmermans F. An insight into circumcised men seeking foreskin reconstruction: a prospective cohort study. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32:611–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-019-0223-y.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1995;95:314–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.95.2.314.

Acknowledgements

TH wishes to acknowledge the late R. Wayne Griffiths, who guided TH on his own restoration journey, assisted him with the co-founding of the National Organization of Restoring Men (NORM), conducted the first organized survey of 240 foreskin restorers in 1995, and whose early efforts inspired TH to undertake this current larger-scale survey. The authors also express their gratitude to the more than 2100 respondents who courageously stepped forward to share their lived experiences on this intensely private matter by submitting completed or partially completed surveys.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This investigation was conceived by TH who developed the survey questionnaire based on decades of listening to the lived experiences of circumcision sufferers and foreskin restorers. He assembled and managed the team of co-authors and contributed significantly to the overall manuscript. LS acted as Principal Investigator, obtained IRB approval from Quinnipiac University, authored the Methods and Result sections, and contributed significantly to the Discussion section. WJ, as statistician, contributed his skills to analyze survey findings, and along with LS authored the Methods and Results sections. RM contributed conceptual knowledge and data analysis and organized the overall presentation flow. BS, as a certified sex therapist, authored the Discussion section relative to sexual impacts. MAB as a physician and author of medical textbooks on male genitalia and the complications of circumcision, provided medical review of the section on penile anatomy, physiology, and circumcision complications. All authors were responsible for the review and editing of the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

TH is the author of two related surveys of circumcision sufferers and is co-founder of the nonprofit charity the National Organization of Restoring Men. TH knew the owners of two restoration device companies and asked for assistance to promote this survey to past customers. Anonymized email lists were supplied to TH at no charge and no promotional promises were made to the companies. LMS has written numerous articles about ethical and human rights implications of circumcision; WAJ has performed statistical analyses and published papers about circumcision; RM appeared in documentaries and videos and has written about the ethics and effects of circumcision; BS appeared in a circumcision documentary for US parents; MABF has published medical textbooks on normal and abnormal prepuce and the short- and long-term physical effects of penile circumcision. The non-profit organization Doctors Opposing Circumcision underwrote the subscription cost (<$300) of the online survey software used in this research.

Ethical approval

This study received Institutional Review Board approval (Protocol #04421) from Quinnipiac University in Hamden, CT, USA, and followed all ethical standards to ensure proper protection of participants and their data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

41443_2023_686_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Unabridged Supplement to Foreskin Restorers: Insights into Motivations, Successes, Challenges and Experiences with Medical and Mental Health Professionals

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Hammond, T., Sardi, L.M., Jellison, W.A. et al. Foreskin restorers: insights into motivations, successes, challenges, and experiences with medical and mental health professionals – An abridged summary of key findings. Int J Impot Res 35, 309–322 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00686-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41443-023-00686-5

This article is cited by

-

Child genital cutting and surgery across cultures, sex, and gender. Part 2: assessing consent and medical necessity in “endosex” modifications

International Journal of Impotence Research (2023)