Abstract

Purpose

This study examined whether participants who learned research results related to a germline CDKN2A variant known to be associated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer and malignant melanoma would pursue confirmatory testing and cancer screening, share the genetic information with health care providers and family, and change risk perceptions.

Methods

Participants were pancreas research registry enrollees whose biological sample was tested in a research laboratory for the variant. In total, 133 individuals were invited to learn a genetic research result and participate in a study about the disclosure process. Perceived cancer risk, screening intentions, and behaviors were assessed predisclosure, immediately postdisclosure, and six months postdisclosure.

Results

Eighty individuals agreed to participate and 63 completed the study. Immediately postdisclosure, carriers reported greater intentions to undergo pancreatic cancer and melanoma screening (p values ≤0.024). Seventy-three percent of carriers (47.5% noncarriers) intended to seek confirmatory testing within six months and 20% (2.5% noncarriers) followed through. All participants shared results with ≥1 family member. More carriers shared results with their health care provider than noncarriers (p = 0.028).

Conclusion

Recipients of cancer genetic research results may not follow through with recommended behaviors (confirmatory testing, screening), despite stated intentions. The research result disclosure motivated follow-up behaviors among carriers more than noncarriers.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Participants in genetic research studies expect to be offered the opportunity to learn their genetic results, especially when those results indicate health risks; moreover, some consider being offered their research results as a sign of respect by the investigators for their research participation.1,2 It is increasingly accepted that individual genetic results that carry potential benefit and are uncovered during research may be offered. It is recommended that research results be offered when the participant can decline to learn their result, there is referral for appropriate clinical follow-up, and the result is actionable.1 However, researchers are not obligated to return research results.3,4,5

As new knowledge emerges, investigators are faced with ethical and practical questions of whether and how they should disclose genetic results to research participants. Unlike in the clinical setting, genetic research results are likely unexpected by participants; disclosing them is optional and aimed to signal to research participants the need to seek further testing and prevention.6,7 A potential benefit of learning genetic research results for participants, particularly those results related to cancer risk, is their ability to engage in prevention and early detection through screening. Nevertheless, investigators who wish to offer results continue to struggle with the “what, when, and how” of doing so, partly because there are limited data charting the course and outcomes of different approaches to returning individual research findings.8

In the context of genetic research results, it is important to understand participants’ intentions and behaviors surrounding the result. Of primary interest is (1) how they act upon this information regarding seeking confirmatory testing in a CLIA-certified laboratory if initial results are obtained in a research laboratory, (2) whether and with whom they share the result, and (3) the extent to which the result, if confirmed, motivates appropriate behaviors, i.e., screening for those with elevated risk due to cancer risk genes. This study sought to increase knowledge on the course of these behavioral outcomes in the context of one approach to disclosing cancer risk related individual genetic research results.

Variants in the tumor suppressor gene cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2a (CDKN2A) are associated with increased risk of pancreatic cancer (PC) and malignant cutaneous melanoma.9,10 It is estimated that by age 80, penetrance for CDKN2A variant carriers may be as high as 58% for PC and 39% for malignant melanoma.9 PC remains one of the most challenging of all cancers. It is often asymptomatic until it has advanced to a late stage, when treatments are less optimal, resulting in a 5-year survival rate of 8.2%11,12. Approximately 5–10% of them are familial PC, which is defined as having at least two first-degree relatives diagnosed with PC.13 Melanoma, however, has a current overall 5-year survival rate of 91.8%14), with 5–12% of cases estimated to be familial.15 Routine screening for PC is currently not recommended for asymptomatic individuals; however, asymptomatic individuals with a genetic predisposition are recommended to undergo surveillance with endoscopic ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pancreas.16,17 Effective screening and prevention measures for melanoma exist, including a full-body skin exam by a clinician and protection from sun exposure.18 A variant in CDKN2A is estimated to account for 30–40% of patients affected by familial PC or familial melanoma.15,19

Offering CDKN2A genetic research results to research participants will inform risk assessment and screening decisions for PC and melanoma. Likewise, given that genetic testing for CDKN2A variants is available clinically, offering results enables cascade testing of the variant among participants’ blood relatives. Understanding the impact on participants is valuable for investigators because it can inform decisions regarding whether to offer results and help guide the development of best practices when investigators offer results.

In research registry settings, existing retrospective and prospective studies on the impact of disclosing CDKN2A variant status focused on melanoma only and revealed mixed results. For example, two studies that returned clinically confirmed genetic test results in person found increased adherence to skin exams20,21 while two studies that returned non–clinically confirmed genetic research results in person found few changes in melanoma screening behaviors.22,23 Given that limited data exist regarding the impact of returning CDKN2A genetic research results, especially those that relate to PC associated perceptions and behaviors, we conducted a prospective disclosure study within a cohort of PC family registry participants. Participants in this registry are from families that experience a high burden of cancer and the investigators elected to disclose the CDKN2A genetic variant findings to participants who wanted to know. Specifically, we aimed to examine the impact of disclosing CDKN2A genetic research results (positive or negative for a specific variant) on participants’ confirmatory testing intention and behavior; communication regarding the result with family and health care providers; PC and melanoma concern; and screening behaviors prior to, at the time of, and six months following disclosure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and participants

This study, Learning About Research Gene Outcomes (LARGO), was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board. This study was a subproject under the parent study, Biospecimen Resource for Pancreas Research, which is an ongoing cohort consisting of family members (blood relatives and spouses/partners) of PC patients recruited at Mayo Clinic. As part of the parent study,24 participants provided a biological sample (saliva or blood) for research and completed a demographic and risk factor questionnaire that included age, sex, race, ethnicity, marital status, education level, number of biological children, and personal cancer history. All participants have a family history of PC and melanoma. In the course of gene discovery and genetic epidemiologic research of PC, biological samples were analyzed for the presence/absence of the variant L16R c.47T>G (p.Leu16Arg) in the CDKN2A gene in several large kindreds that segregated this variant. At the time of the study, this variant was classified as a variant of uncertain significance,25 but our research showed it was likely pathogenic and it is now classified as pathogenic/likely pathogenic in ClinVar.9,10,26,27,,27 Individuals whose samples were tested were notified via mail that their sample was analyzed for one specific genetic variant associated with cancer and invited to learn their genetic research result by phone and to participate in the LARGO study. Participants could choose to (1) learn the result and participate in LARGO, (2) learn the result but not participate in LARGO, or (3) decline both opportunities. One repeat mailing was sent to initial nonresponders.

Procedures and measures

Informed consent was received from all LARGO participants. The LARGO study included data collection time points at predisclosure (survey 1), immediately postdisclosure (survey 2), and six months postdisclosure (survey 3). The choice of psychosocial constructs for the LARGO surveys was guided by dominant constructs within published literature on return of genetic results (e.g., family communication, satisfaction with genetic counseling, and psychological impact) and theoretical constructs derived from an integrative model of behavior including determinants of behavioral intention (e.g., affect/emotion and beliefs),28 as well as predictors of behavior such as knowledge/skills surrounding confirmatory testing and cancer screening. Survey 1 was mailed with the invitation letter to learn results and included questions pertaining to PC and melanoma concern with the response options not at all, slightly, moderately, extremely concerned; perceived likelihood of developing PC (very unlikely, somewhat unlikely, somewhat likely, very likely, I have no feeling or opinion on my chances of getting pancreatic cancer); and chance of developing melanoma (below average, average, above average). Additional items assessed communicating with health care providers about PC and melanoma, with the options no; yes, about my risk for it; yes, about how to prevent it; yes, about screening for it. Screening intentions surrounding PC (“What are your thoughts about getting an endoscopic ultrasound exam or MRI/MRCP within the next six months to check for pancreatic cancer?”) and melanoma (“What are your thoughts about getting a skin exam within the next six months to check for melanoma?”) were assessed with the following options: thinking about it, definitely planning on it, not planning on it, have not thought about it.

Upon return of a completed survey 1, disclosure of genetic research results under the LARGO protocol was scheduled. Typically, negative results are returned by mail while positive results are returned in person. However, in this study, in-person delivery was infeasible because participants lived across the United States. Therefore, all results were disclosed over the telephone by the gene discovery principal investigator (G.M.P.), who is certified by the American Board of Medical Genetics. Disclosure calls were audio-recorded after explicit permission from participants. All participants received a clear indication of the status of the L16R variant in the CDKN2A gene (whether one was positive for the variant [carrier] or negative [noncarrier]) and the implications of the result with regard to PC and melanoma risk. Specifically, participants were informed that if the result is confirmed in a CLIA-certified lab, for carriers, the lifetime risk for PC and melanoma could be up to 60–70% and 30–40%, respectively; for noncarriers, their lifetime risks for PC and melanoma are at the general population level. G.M.P. also discussed the difference between research and CLIA-certified laboratories, recommended that the research result be confirmed in a CLIA-certified laboratory and shared with their health care provider, and provided PC and melanoma prevention counseling that included recommendations regarding diet, physical activity, sun protection, limiting alcohol consumption, and not smoking. The counseling was not tailored based on self-reported cancer screening and prevention behaviors. The terms “mutation” and “variant” were both used during the disclosure call.

Participants were informed that they would receive a written follow-up letter in the mail summarizing their result and suggestions for confirmatory testing, as well as PC and melanoma screening and prevention.13,29,30 The disclosure concluded when all questions about the genetic result were answered to the participant’s satisfaction and G.M.P. disengaged from the call and exited the room. A trained interviewer (E.R.L. or C.R.B.) recorded observations (i.e., checklist items and field notes) during the disclosure to describe the participant’s engagement in the conversation; G.M.P. also recorded observations independently after exiting the room.

During the same telephone call, the interviewer initiated survey 2 after the result disclosure and received permission to audio-record the survey. The survey included checking participants’ understanding, i.e., knowing their variant status and what the variant was related to (risk of PC and melanoma), and capturing initial reactions to hearing the result. Additional questions addressed satisfaction with the disclosure process, and intentions regarding sharing their result with health care providers and family, pursuing confirmatory testing, and seeking PC and melanoma screening. Approximately six months after disclosure, survey 3 was mailed with one repeat mailing to initial nonresponders. This survey repeated questions from surveys 1 and 2 regarding PC and melanoma related perceptions and behaviors as well as confirmatory testing and communication of the result with health care providers and family.

The current paper presents data regarding perceptions (cancer concern and perceived risk) and behaviors (communicating with health care providers, attending cancer screening, sharing the result with family, and pursuing confirmatory testing) following disclosure of CDKN2A variant status among research participants from PC kindreds.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using SAS (Release 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 1997). Descriptive data are presented as frequencies (n) and percentages (%), with missing data excluded. For ease of presentation, we dichotomized responses to cancer concern (lack of concern [not at all/slightly concerned] versus moderate/extreme concern) and screening intentions (not planning [have not thought about it/not planning/thinking about it] versus definitely planning). For perceived PC risk, “very unlikely” and “somewhat unlikely” were combined into one category and “somewhat likely” and “very likely” were combined into one category. Group comparisons were evaluated using Welch’s t tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Statistical significance was declared at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

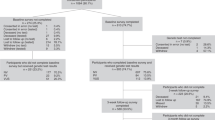

A total of 133 participants were invited to learn their genetic research result and 93 (69.9%) responded affirmatively (Fig. 1). Specifically, 80 (60%) elected to learn their results and enroll in the LARGO study, 13 (9.8%) elected to learn their results but declined LARGO participation, and 7 (5.3%) declined learning results; 33 (24.8%) did not respond. Seventy-three (91.3%) of those who returned survey 1 completed the result disclosure process. Seventy-two participants completed survey 2; 1 participant withdrew immediately after learning the result, and 1 participant completed survey 2 but requested not to receive survey 3. Of the 71 participants who were mailed survey 3, 63 (88.7%) returned a completed survey. Fifteen participants were carriers of the variant, 40 were blood relative noncarriers, and 8 were spouses. Data from the carriers and blood relative noncarriers who completed the study at all three time points were used in the analyses. Data from the spouses were excluded.

Participants self-identified as white, non-Hispanic, with a median age of 57 years for carriers (range 37–75) and 56 years for blood relative noncarriers (range 28–90). Most participants were female (65.5%), married (76.4%), and reported having one or more biological children (80%). Six (40%) carriers reported a personal history of cancer, as compared with ten (25%) blood relative noncarriers (p = 0.326). No differences in sociodemographic characteristics by variant status reached statistical significance (Table 1).

All participants correctly identified whether or not they carried the variant. Carriers identified that the variant was related to an increased risk of PC and melanoma.

PC concern, perceived risk, screening intentions, and behavior

Carriers had greater concern for developing PC compared with noncarriers at predisclosure (p = 0.009) and six months postdisclosure (p < 0.001) (Table 2). At predisclosure, there was no difference between carriers and noncarriers regarding perceived lifetime risk of PC; however, at six months postdisclosure, 100% of carriers versus 56.5% (n = 22) of noncarriers indicated they were “somewhat” or “very” likely to develop PC in their lifetime (p = 0.008) (Table 2). At disclosure, 85.7% (n = 12) of carriers indicated that they planned to have their pancreas checked in the next six months; 46.7% (n = 7) reported doing so six months postdisclosure (Table 3).

Melanoma concern, perceived risk, screening intentions, and behavior

As with PC, carriers had greater concern for developing melanoma compared with noncarriers at predisclosure (p = 0.022) and six months postdisclosure (p = 0.021). However, this difference became nonsignificant when seven participants with melanoma history were excluded from analysis (p = 0.095 and p = 0.211) (Table 2). Compared with noncarriers, a greater proportion of carriers also reported “above average” likelihood of developing melanoma in their lifetime, both at predisclosure (p < 0.001) and six months postdisclosure (p = 0.002). Excluding those with melanoma history did not change the results (p = 0.002 and p = 0.033) (Table 2). At disclosure, 93.3% (n = 14) of carriers indicated that they intended to have a skin exam in the next six months; at six months postdisclosure, 71.4% (n = 10) reported receiving an exam (Table 3). Among noncarriers, 30.8% (n = 12) reported having a skin exam in the last six months.

Communication with health care providers about cancer

Prior to disclosure, 60% (n = 33) of blood relative participants reported that they had communicated with their health care provider about PC and 63.6% (n = 35) about melanoma (including seven participants with melanoma history). At six months postdisclosure, 92.9% of participants who learned they were carriers (n = 13) reported communicating with their health care providers about PC, compared with 41% of noncarriers (n = 16; p = 0.001). At six months postdisclosure, 85.7% (n = 12) of carriers had communicated with their health care providers about melanoma compared with 43.6% (n = 17; p = 0.011) of noncarriers (Table 4).

Communication regarding the genetic research result

At disclosure, all carriers indicated that they “definitely plan to” communicate with their health care providers about the result in the next 6 months, compared with 82.5% of noncarriers (n = 33, p = 0.17). At six months postdisclosure, 78.6% (n = 11) of carriers communicated to their health care providers about the result compared with 41% (n = 16) of noncarriers (p = 0.028). Among those who communicated with their providers about the result, 90.9% (n = 10) of carriers and 93.8% (n = 15) of noncarriers (p = 1.00) discussed PC and melanoma risks, attending cancer screening, and importance of a healthy lifestyle for cancer prevention. At disclosure, all participants intended to tell at least one family member about the research result and at six months postdisclosure, all participants reported telling at least one family member (Table 4).

Confirmatory testing

Testing for the genetic variant reported in this study was conducted in a research laboratory; therefore, all participants were instructed to have their results confirmed in a CLIA-certified laboratory. Despite these instructions, 73.3% (n = 11) of carriers and 47.5% (n = 19) of noncarriers indicated during survey 2 that they intended to seek confirmatory testing. At six months postdisclosure, 20% (n = 3) of carriers and 2.5% (n = 1) of noncarriers reported seeking confirmatory testing. Among those who did not, five carriers and four noncarriers decided to seek testing in the future, two carriers and 40% of noncarriers (n = 15) had not decided, and around one-third of carriers (n = 4) and noncarriers (n = 14) indicated that they decided not to seek retesting.

DISCUSSION

This study examined the impact of returning individual genetic research results related to cancer risk among participants in a PC research registry. Specifically, this investigation examined intentions and behaviors regarding confirmatory testing of the result, PC and melanoma screening, and cancer risk communication with family and health care providers among individuals found to test positive or negative for a specific CDKN2A variant.

Consistent with other reports,1,2 a majority of individuals who were invited to learn a genetic research result accepted the invitation. In this study, both positive and negative results were disclosed, and the implications of their carrier status were explained. Carriers and noncarriers were significantly different (in the expected direction) at six months postdisclosure regarding PC concern and perceived lifetime risk for PC and melanoma, and cancer screening intentions. While there was greater concern among carriers regarding their PC risk, and most carriers reported intentions to seek cancer screening, not all carriers who intended to be screened did so within six months. Nonetheless, most carriers who were not screened at six months postdisclosure planned to seek cancer screening in the near future, suggesting that a longer follow-up interval may capture additional screening behavior.

There were differences between participants’ perceptions and behaviors concerning PC versus melanoma. Regardless of variant status, more participants expressed “moderate/extreme” concern about PC compared with melanoma both at predisclosure and six months postdisclosure, likely due to participants’ understanding of the two cancers. In addition, more carriers received melanoma screening than PC screening at six months postdisclosure, likely reflecting that melanoma screening is more readily accessible and less invasive than current methods of PC screening. Future research should explore the various factors that disrupt the intention–behavior relationship, including barriers to cancer screening among those at increased genetic risk as well as multilevel disincentives such as high cost, inadequate insurance coverage, lack of access to clinics providing specialty care, and clinician unfamiliarity with genetic results.

Consistent with previous research,31 a greater proportion of carriers than noncarriers reported sharing their result and communicating about cancer with their health care providers. This finding suggests that carriers perceived greater urgency in communicating about cancer risk than did noncarriers, having done so within six months of learning the result. It is important to note that in most cases, these conversations were likely initiated in the absence of confirmatory testing. As noted above, a longer follow-up interval may have revealed additional conversations among noncarriers, particularly as they occurred with health care providers during an annual visit that exceeded the six-month time point.

At disclosure, a majority of participants stated an initial intention to pursue confirmatory testing as advised; however, even after receiving a follow-up letter reminding them of this suggestion, few participants followed through on their intention. In fact, one-third of all participants decided not to seek retesting at six months postdisclosure. For some participants, this decision may reflect institutional trust, i.e., the results were correct and did not need to be confirmed. Our findings should be replicated in other settings and populations; further, research participants may not fully appreciate the difference between research versus clinical genetic testing results and the need for validating research results. Further investigation that leverages experimental methods and perspectives from health communication may uncover effective ways to convey this message. In addition, some participants’ inaction may be due to access barriers. Thus, providing assistance in locating a CLIA-certified laboratory that is convenient to participants and offering to cover the cost of testing that is not covered by insurance may improve confirmatory testing uptake.

The present research’s participation and six-month follow-up rates are moderately high, and is equivalent to, or higher than, previous studies on return of genetic research results.22,31,32 Limited data exist on why research participants accepted or refused offers to receive results. Data based on hypothetical scenarios suggest that individuals who see utility in the results and/or are altruistic are more interested in receiving results while individuals who anticipate negative psychological consequences, such as worry and anxiety, are less interested.33,34 Additionally, unpublished data from our group suggest that individuals who view biomedical research and science favorably were more interested in receiving genetic research results. These findings highlight the importance to better understand how to effectively communicate the opportunity of receiving genetic results to research participants.

Research results in this study were communicated by telephone. To ensure participants had accurate information, a summary letter including information about the variant and recommendations for confirmatory testing, cancer screening, and prevention was mailed. To date, no data directly compared outcomes of telephone and in-person return of genetic research results, thus we cannot speculate how the delivery mode may have influenced results. However, in clinical genetic testing, research comparing telephone versus in-person counseling found that telephone counseling is comparable to in-person counseling for outcomes such as satisfaction, psychological reactions, and information recall, and is more cost-effective and accessible.35,36 Likewise, our participants reported high satisfaction regarding the disclosure/genetic counseling call37 (M = 3.51, SD = 0.36 on a 0 to 4 scale) and there was no difference by variant status (p = 0.870). These findings are reassuring given resources for returning research results are often limited. However, future research evaluating the long-term psychosocial and behavioral outcomes of different result delivery modes is needed.

This study’s strengths include its novelty of returning a genetic research result to consenting adult individuals in high-risk cancer families. We returned results to both carriers and noncarriers of the CDKN2A variant, enabling comparisons. The moderately high participation and six-month follow-up rates are strengths, which limit the potential for selection bias. Additionally, all disclosures were completed by a single individual and all postdisclosure interviews were completed by one of two trained interviewers thereby limiting variation in the disclosures and interviewer bias.

The study’s weaknesses include its small, homogeneous sample, which limited our ability to make inferences about diverse populations, or other genes or cancers from the data. Additionally, self-reported behavioral data (e.g., cancer screening) may be influenced by social desirability bias. However, we measured social desirability38 at predisclosure and the average score was very low (M = 26.4, SD = 24.8, range: 0–100) and did not differ by variant status (p = 0.86). Importantly, social desirability and behavioral outcomes were not significantly correlated (r ranged from 0.002 to 0.205, p-values were non-significant) suggesting that self-reports of behavior were likely unbiased by the tendency to create a positive impression. Another concern is that because research laboratories are not typically required to adhere to CLIA standards, findings can lead to false positive results that could potentially increase undue worry and stress and false negative results that could potentially hinder cancer detection and prevention. Regarding test results returned in this study, the Mayo Clinic laboratory that performed the genetic analysis was a research core lab in the Medical Genome Facility, aligned with the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, and the quality of work followed high standards. The risks of false positive and false negative results were deemed acceptable.

In conclusion, while intentions to pursue PC and melanoma screening following genetic research result disclosure were strongly endorsed, a majority of individuals did not carry out the stated intentions, particularly for PC screening. Although carriers were more likely to act upon the results than noncarriers, it appears that for many, a single disclosure and counseling interaction will not be sufficient to motivate appropriate behavioral responses regarding confirmatory testing or cancer screening. Further research is needed to identify specific barriers that interrupt the intention–behavior relationship in this context. These studies should consider including a longer (>6 months) follow-up period to allow more time for behavioral responses. Finally, research is needed that explores whether strategies such as motivational interviewing or setting implementation intentions during the disclosure conversation may prove beneficial.39,40

References

Jarvik GP, Amendola LM, Berg JS, et al. Return of genomic results to research participants: the floor, the ceiling, and the choices in between. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:818–826.

Bollinger J, Scott J, Dvoskin R, Kaufman D. Public preferences regarding the return of individual genetic research results: findings from a qualitative focus group study. Genet Med. 2012;14:451–457.

Wolf SM, Lawrenz FP, Nelson CA, et al. Managing incidental findings in human subjects research: analysis and recommendations. J Law Med Ethics. 2008;36:219–248.

Fabsitz RR, McGuire A, Sharp RR, et al. Ethical and practical guidelines for reporting genetic research results to study participants: updated guidelines from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010;3:574–580.

Beskow LM, Burke W. Offering individual genetic research results: context matters. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:38cm20.

Burke W, Evans BJ, Jarvik GP. Return of results: ethical and legal distinctions between research and clinical care. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2014;0:105–111.

Evans BJ. Minimizing liability risks under the ACMG recommendations for reporting incidental findings in clinical exome and genome sequencing. Genet Med. 2013;15:915–920.

Wong CA, Hernandez AF, Califf RM. Return of research results to study participants: uncharted and untested. JAMA. 2018;320:435–436.

McWilliams RR, Wieben ED, Rabe KG, et al. Prevalence of CDKN2A mutations in pancreatic cancer patients: implications for genetic counseling. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:472–478.

Hu C, Hart SN, Polley EC, et al. Association between inherited germline mutations in cancer predisposition genes and risk of pancreatic cancer. JAMA. 2018;319:2401–2409.

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30.

Klein AP. Genetic susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2012;51:14–24.

Petersen GM. Familial pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:548–553.

National Cancer Institute. Cancer stat facts: melanoma of the skin. 2017. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html. Accessed April 16, 2018.

Eckerle Mize D, Bishop M, Resse E, Sluzevich J. Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome. In: Riegert-Johnson DL, Boardman LA, Hefferon T, Roberts M, eds. Cancer Syndromes. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information; 2009: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7030/. Accessed April 10, 2019.

Canto MI, Harinck F, Hruban RH, et al. International Cancer of the Pancreas Screening (CAPS) Consortium summit on the management of patients with increased risk for familial pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:339–347.

Syngal S, Brand RE, Church JM, et al. ACG clinical guideline: genetic testing and management of hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:223–262.

Curiel-Lewandrowski C, Chen SC, Swetter SM, Melanoma Prevention Working Group-Pigmented Skin Lesion Subcommittee. Screening and prevention measures for melanoma: is there a survival advantage? Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:458–467.

Ghiorzo P. Genetic predisposition to pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10778–10789.

Aspinwall LG, Taber JM, Leaf SL, Kohlmann W, Leachman SA. Melanoma genetic counseling and test reporting improve screening adherence among unaffected carriers 2 years later. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1687–1697.

Kasparian NA, Meiser B, Butow PN, Simpson JM, Mann GJ. Genetic testing for melanoma risk: a prospective cohort study of uptake and outcomes among Australian families. Genet Med. 2009;11:265–278.

Christensen KD, Roberts JS, Shalowitz DI, et al. Disclosing individual CDKN2A research results to melanoma survivors: interest, impact, and demands on researchers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:522–529.

Glanz K, Volpicelli K, Kanetsky PA, et al. Melanoma genetic testing, counseling, and adherence to skin cancer prevention and detection behaviors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:607–614.

Petersen GM, de Andrade M, Goggins M, et al. Pancreatic cancer genetic epidemiology consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:704–710.

Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Benson M, et al. ClinVar: improving access to variant interpretations and supporting evidence. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(D1):D1062–D1067.

ClinVar. NM_000077.4(CDKN2A):c.47T>G (p.Leu16Arg). ClinVar. 2018; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/variation/219815/. Accessed 21 October 2018.

Marks D, Horn IP, Hogenson TL, et al. Reducing protein stability underlies the protumoral function of L16R(47T>G) CDKN2A, a mutation associated with familial pancreatic cancer. Paper presented at: American Assocaition for Cancer Research (AACR) Special Conference: Pancreatic Cancer: Advances in Science and Clinical Care; September, 2018; Boston, MA.

Rimer BK, Glanz K. Theory at a Glance: A Guide for Health Promotion Practice (Second Edition). Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/research/theories_project/theory.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2019.

Canto MI, Almario JA, Schulick RD, et al. Risk of neoplastic progression in individuals at high risk for pancreatic cancer undergoing long-term surveillance. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:740–.e742.

Vasen H, Ibrahim I, Ponce CG, et al. Benefit of surveillance for pancreatic cancer in high-risk individuals: outcome of long-term prospective follow-up studies from three European expert centers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2010–2019.

Graves KD, Sinicrope PS, Esplen MJ, et al. Communication of genetic test results to family and health care providers following disclosure of research results. Genet Med. 2014;16:294–301.

Bradbury AR, Patrick-Miller L, Egleston BL, et al. Returning individual genetic research results to research participants: uptake and outcomes among patients with breast cancer. JCO Precision Oncol. 2018;2:1–24.

O’Daniel J, Haga SB. Public perspectives on returning genetics and genomics research results. Public Health Genomics. 2011;14:346–355.

Meulenkamp TM, Gevers SK, Bovenberg JA, Koppelman GH, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Smets EM. Communication of biobanks’ research results: what do (potential) participants want? Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2482–2492.

Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:618–626.

Jenkins J, Calzone KA, Dimond E, et al. Randomized comparison of phone versus in-person BRCA1/2 predisposition genetic test result disclosure counseling. Genet Med. 2007;9:487–495.

DeMarco TA, Peshkin BN, Mars BD, Tercyak KP. Patient satisfaction with cancer genetic counseling: a psychometric analysis of the Genetic Counseling Satisfaction Scale. J Genet Couns. 2004;13:293–304.

Hays RD, Hayashi T, Stewart AL. A five-item measure of socially desirable response set. Educ Psychol Meas. 1989;49:629–636.

Gollwitzer PM, Sheeran P. Implementation intentions and goal achievement: A meta‐analysis of effects and processes. In: Zanna M, ed. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2006:69–119.

Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. Am Psychol. 2009;64:527–537.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants R01 CA97075 and R01 CA208517 and the Rolfe Foundation for Pancreatic Cancer. We gratefully acknowledge the clinical expertise of Noralane Lindor, Robert R. McWilliams, and Katrina Pedersen; the study coordination efforts of Bridget Rathbun; and the data management support of Que Luu, Megan Reichmann, Ryan Wuertz, and Sarah Amundson.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leof, E.R., Zhu, X., Rabe, K.G. et al. Pancreatic cancer and melanoma related perceptions and behaviors following disclosure of CDKN2A variant status as a research result. Genet Med 21, 2468–2477 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0517-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0517-y