Abstract

Purpose

We performed a systematic review of the ethical, social, and cultural issues associated with delivery of genetic services in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Methods

We searched 11 databases for studies addressing ethical, social, and/or cultural issues associated with clinical genetic testing and/or counselling performed in LMICs. Narrative synthesis was employed to analyze findings, and resultant themes were mapped onto the social ecological model (PROSPERO #CRD42016042894).

Results

After reviewing 13,308 articles, 192 met inclusion criteria. Nine themes emerged: (1) genetic counseling has a tendency of being directive, (2) genetic services have psychosocial consequences that require improved support, (3) medical genetics training is inadequate, (4) genetic services are difficult to access, (5) social determinants affect uptake and understanding of genetic services, (6) social stigma is often associated with genetic disease, (7) family values are at risk of disruption by genetic services, (8) religious principles pose barriers to acceptability and utilization of genetic services, and (9) cultural beliefs and practices influence uptake of information and understanding of genetic disease.

Conclusion

We identified a number of complex and interrelated ethical, cultural, and social issues with implications implications for further development of genetic services in LMICs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

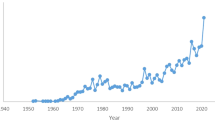

Clinical genetic testing detects DNA anomalies that may have pathological consequences. A standard part of management for many inherited disorders,7 its aim is to predict the risk of developing disease and transmitting disease-causing variants to offspring. Genetic counseling assists individuals in understanding test results and their consequences. As technology has evolved and become increasingly more cost-effective, genetic testing services have been introduced in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), usually through research initiatives13,14,15,16,17,18 or formal international partnerships.19,21,22 In contrast, genetic counseling has not developed in a similar robust fashion, and remains largely a Western concept and profession. Indeed, the number of genetic counselors available globally is far lower than the need for their services, frequently resulting in physicians bearing much of the responsibility for genetic counseling.23,24,25 In LMICs, where physicians have bigger patient loads and often limited training in medical genetics, it remains challenging to effectively educate and support patients.

In contrast to the push to bring genomic science from “lab to village,”1,2,3,4,5,6,26 there is little focus on how to build clinical genetic services in LMICs in a responsible, ethical, and culturally appropriate manner. Much of the literature reporting on development of genetic services in LMICs has largely commented on capacity building and tecnical success.8,9,10,11,12,20 Several experts have recognized the urgent need for a thoughtful approach, grounded in ethics, to implement genetic services in LMICs so that the unique needs of those patient populations are met.27,28 A growing number of studies are beginning to address ethical and sociocultural issues in genetics.29,30,31,32 This knowledge synthesis aims to determine the breadth of work done in this area, and uncover the ethical, social, and cultural issues that are relevant to implementation of genetic services in LMICs. The results will inspire policy recommendations and ultimately define areas of new areas of investigation.

Materials and methods

Protocol and registration

This study was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist (Additional File 1). The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (#CRD42016042894). The detailed protocol has been previously published.33

Briefly, an integrated knowledge translation approach was used to engage end-users throughout the study. An End-User Committee met three times over the course of the systematic review to (1) discuss methodology, (2) review data collection and analysis, and (3) review synthesized results. The search strategy was developed with the assistance of an information scientist, searching MEDLINE, Embase, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Cinahl, LILACs, CCRCT, CDSR, DARE, BiblioMap, HealthPromise for studies between January 1, 1990 and July 12, 2013 (Additional File 2). Studies were included if they reported on (1) clinical genetic testing or genetic counseling services (where genetic counseling refers to both formal genetic counseling, as well as other forms of communication from healthcare professional to patient regarding heritability and/or genetics of a disorder), (2) populations in LMICs as defined by the World Bank,34 and (3) ethical, social, and/or cultural factors that influence the implementation of genetic testing and/or counseling. Studies performed in high-income countries (HICs) and/or states/territories (e.g., Hong Kong, Taiwan)35,36 were excluded. Studies focused solely on the technological aspect of genetic testing (e.g., development and/or application of a novel technique) and studies related to basic genomic research (e.g., such as those looking at migration, ethnicity, or genomics of populations) were also excluded. Studies in languages other than English were excluded for practical reasons, as were those published before 1990, which were presumed to be outdated.

Bibliographic data of identified studies were managed using EPPI-Reviewer 4 (University College London, UK). A data extraction form was developed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Quality appraisal was performed using the QUALSYST quality assessment tool, which consists of a separate checklist for quantitative and qualitative research studies that assesses “the extent to which the design, conduct and analyses minimize errors and biases.”37 The QUALSYST tool was developed specifically for assessment of studies from a wide variety of disciplines. A narrative synthesis was performed, following the framework established by the Economic and Social Research Council,38 as described in our previously published protocol.33 The data was organized using NVivo-11 (QSR International). Two authors (AZ, HD) independently conducted an inductive, realist analysis to generate descriptive codes. Codes were refined until consensus among authors was reached, and applied to meaningful data points to generate themes. To explore relationships within and between all studies, themes were mapped onto the social ecological model, a conceptual framework based on ecological systems theory, which proposes that individual health outcomes are influenced by interactions with the greater environmental, social, and cultural context.39,40 Further details are provided in the published study protocol.33

Role of funding source

There was no funding source for this study. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

Study characteristics

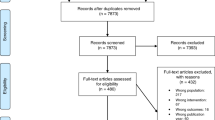

The search strategy identified 19,618 records, of which 13,038 remained after removing duplicates. After applying inclusion/exclusion criteria from review of titles and abstracts, 915 remained. Full manuscripts were accessible for 638/915. Review of full manuscript excluded another 447. One study was identified by hand-searching, to arrive at 192 included articles (Fig. 1, Additional File 3).

Included studies represented South Asia (40), Middle East and North Africa (38), Latin America and the Caribbean (34), Africa (32), East Asia (21), Eastern Europe (18) or a combination (9) (Fig. 2). Studies covered blood disorders (59), neurological disorders (17), chromosomal abnormalities (12), cancer (11), or other disorders (11). Studies used quantitative (136), mixed (29), or qualitative (27) methods. Observational study designs were most common (170), followed by knowledge syntheses (15) and experimental studies (7). The average QUALSYST score was 82% (median 85%; range 60–100%).

Themes

Thematic analysis revealed nine key themes: two ethical, four social, and three cultural issues.

Ethical issues

Theme 1. Genetic counseling has a tendency of being directive

Clinical genetic counseling in LMICs tends to be directive.41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54 Caregivers and patients, especially those of low socioeconomic status, prefer clinicians to make final decisions, and have little desire to learn more about treatment options.51,52,53 Some clinicians approach genetic counseling as a means to reduce birth defects and deleterious genes in the population, and improve the affected family’s quality of life,50,54,55,56,57,58 an attitude described as having eugenic tendencies.55,56,58 This acceptability of eugenics is reportedly more common among clinicians in LMICs than HICs.59

Clinicians tend to be accepting of termination of pregnancy following prenatal detection of genetic disease.41,42,45,47,50,60,61,62,63,64 The implicit or explicit advice to patients is termination of pregnancy; clinicians may use negative language to influence the patient’s choice to terminate pregnancy, without directly suggesting it.58 Information leaflets studied in LMICs were significantly more negative in their description of genetic diseases as compared with similar material in HICs.58,65,66

Theme 2. Genetic services have psychosocial consequences that require improved support

Studies investigating the psychological effects of genetic services found that patients were commonly in denial of their risk, contributing to an unwillingness to undergo genetic screening.67,68,69 Fear and anxiety is associated with genetic testing, particularly related to the implications of a positive test result.46,48,51,59,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82 Psychological distress affects extended family members.46,67,71,74,76,83,84,85,86,87,88,89 Individuals with a genetic diagnosis feel like a burden to their families, and experience guilt or blame.49,67,83,86,90,91,92

Studies identify a need to address psychological effects of a genetic diagnosis and enhance patient coping.73,84,85,93,94,95,96,97 Patients commonly express a need for genetic counseling following testing, are generally willing to join a support group, and desire psychological follow-up.73,80,84,94,98

Social Issues

Theme 3. Medical genetics training is inadequate

For clinicians, a lack of knowledge about genetic diseases is a common barrier to their capacity in counseling patients.51,70,99,100 Clinicians do not feel confident in providing information or counseling patients regarding genetic disease,49,101 and can be dismissive when patients and families ask many follow-up questions.70,102,103 Many clinicians report that their medical education in genetics was insufficient.70,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112

Studies reveal an absence of practice guidelines and ethical codes for genetic services.54,57,101,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120 Informed consent and protection of patient rights are underdeveloped in many LMICs.48,65,66,99,121,122,123 There is little recognition of genetic counseling as a profession, so the responsibility is nearly always the physician’s.49,54,91,120 A number of studies explored opportunities for medical staff other than physicians, such as nurses and midwives, to be involved in genetic services.73,106,107,110 Medical staff and physicians are accepting of additional educational programs to enhance their genetic knowledge.100,105,108,112,124

Theme 4. Genetic services are difficult to access

Financial barriers were reported to be a common hindrance to patients’ acceptance and utilization of genetic services.41,50,69,78,80,85,89,91,95,102,116,119,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134 Although insurance coverage and subsidies paid by the government in some LMICs improve access to these services, high cost of genetic services remains a barrier, especially for low-income and rural patients.83,116,125,135,136,137 When genetic services are not widely available, patients often must travel long distances to access them, incurring high costs.41,83,85,117,129,137 It is also a financial challenge for the healthcare system to provide the services to meet demand.48,54,99,109

Many patients do not undergo genetic testing due to their perception that genetic disorders cannot be treated.49,60,61,102,138 The perceived lack of medical support and treatment options also contributes the decision to terminate a pregnancy after a positive prenatal diagnosis.132,139,140

Theme 5. Social determinants affect uptake and understanding of genetic services

Awareness and knowledge of genetic diseases and genetic services is correlated with education and socioeconomic status.48,127,130,141,142,143,144,145,146 Educated individuals seek out diverse resources to understand their condition, including service providers, websites, and books; conversely, those with lower literacy ask fewer questions, and find it challenging to cope.48 Simplified communication tools, such as charts, and using lay terminology in the local language, can overcome socioeconomic barriers and improve understanding.83,91,147

Acceptability of genetic testing and counseling is also positively correlated with education and socioeconomic status.29,53,83,90,97,126,148,149,150 Individuals from rural areas and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds face financial and other challenges in accessing genetic services or termination of pregnancy.85,116,137

Theme 6. Social stigma is often associated with genetic disease

Patients worry about the effects of social stigma associated with genetic disease.46,48,67,74,76,77,81,103,119,144,151,152,153,154,155,156 Patients are hesitant to disclose their genetic results to extended family and community, and many experience social isolation after such disclosure.76,77,81,103,134,152,155 Affected individuals and their families experience discrimination when seeking marriage prospects.48,57,81,103,134,154 The negative portrayal of genetic diseases in the media (e.g., “children who should not have been born”) is a significant factor contributing to stigma.70,91

Cultural issues

Theme 7. Family values are at risk of disruption by genetic services

For many families, having an “ideal family size” is important to family planning.78,89,102,137,139,145,157,158 Regardless of the number of children affected by a genetic disease, families continue to have more children so that the number of healthy children reflects the average family size in the general population.102,145

Family members and spouses, especially mothers-in-law and husbands, hold strong influence over decisions following prenatal diagnosis.31,46,55,59,86,122,139,140,141,144,152,159 The Western model of individual autonomy may not be appropriate for collectivist cultures, where the individual’s choice incorporates opinions of others.65,74,89,122,152,160 Patients often feel it is the clinician’s responsibility to inform their family members of their risk;59,74,76,88,103,134,144,153,160,161,162 however, clinicians often feel this is the patient’s role.55,88,163 Where consanguinity is common, family members are primarily in control of marriage and reproductive decisions.68,164 Consanguineous couples are often less aware of genetic risks than nonconsanguineous couples.131,157,165,166

Women often face family pressure to give birth to healthy children, and experience blame when a child is born with a genetic disease.46,48,49,80,86,139,143,157,167 Marital problems, including divorce, often occur if a child is affected or if the wife is a carrier.78,86 Where arranged marriages are common, women with carrier status have fewer marriage prospects.48,57,75,81,132,134,168

Theme 8. Religious principles pose barriers to acceptability and utilization of genetic services

A number of studies identify religious principles that oppose termination of pregnancy as significant barriers to acceptance and utilization of genetic services.29,45,47,69,89,97,128,134,148,151,167,169,170,171 Some individuals are hesitant to utilize genetic services to avoid the recommendation to terminate a pregnancy.45

In Islam, fatwas (religious laws) guide decisions regarding termination of pregnancy, dependent on the severity of the condition and gestational age.134,172,173 In Pakistan, fatwas allow for termination of pregnancy in cases where the healthcare professional advises it.154,172,174

Theme 9. Cultural beliefs and practices influence uptake of information and understanding of genetic disease

Karma, curses, superstitions related to certain behaviors during pregnancy, and perceived punishment from God are commonly held beliefs regarding the origins of genetic diseases.46,51,67,72,74,78,139,143,160,164,175,176 Without a biological understanding of genetic disease, cultural beliefs can deeply affect attitudes toward affected individuals.136,175 Cultural beliefs are more familiar, and traditional medicine is more accessible in the community.143,177 Traditional healers are viewed as integral members of the community, with affordable and relatable service; they may be the health service provider of choice due to a perception that there is nothing more effective available.143

Cultural beliefs and practices may impede understanding of genetics.47,57,72,178,179 Cultural beliefs can be effectively integrated and confronted in the clinical setting. Clinicians can directly speak about these misconceptions to assuage guilt.91 Incorporating traditional cultural practices, such as symbols, can facilitate understanding of genetics among patients.161

The social ecological model for improvement of genetic services

The nine themes were mapped onto the five levels of the social ecological model: individual, interpersonal, institutional/organizational, community, and public policy (Fig. 3). At the individual level, a patient’s socioeconomic status (theme 5), religious principles (theme 8), cultural beliefs (theme 9), and psychosocial wellbeing (theme 2) were all factors that shaped attitudes toward and affect access to genetic services. Interpersonal factors included the effect of family values (theme 7), psychosocial effects on family members (theme 2), marriage prospects (theme 6), and directive counseling (theme 1). Institutional/organizational factors were issues regarding genetic service provision and affordability (theme 4), lack of clinical guidelines for genetic counseling (theme 3), lack of psychosocial support (theme 2), and the eugenic tendency of genetic services (theme 1). At the community level, issues include social stigma of individuals and families with genetic disease (theme 6), religious principles (theme 8), and cultural beliefs and practices (theme 9). Factors at the public policy level include inadequate medical training and guidelines (theme 3), and healthcare costs for genetic services (theme 4).

Discussion

Genetic counseling is an educational and communication process for individuals and families who have, or may be at risk for, a genetic disease. It is meant to help families cope with their disease, and understand the meaning and consequences of genetic testing. In many parts of the world, largely in HICs, genetic counseling is a formal process, delivered by professionals with graduate degrees in genetic counseling or medical genetics. In LMICs, genetic counseling is generally delivered less systematically; healthcare practitioners have limited training in genetics, and the added knowledge provided from genetic testing is often not available in those settings.

Yet, things are changing. The introduction of genomic technology in LMICs is expanding capacity in clinical genetic testing and genomic research with the potential to revolutionize the understanding, care, and clinical treatment for communicable and noncommunicable diseases.180,181,182 However, without sufficient attention paid to the ethical, social, and cultural implications of such services, technological advances may fall short of their potential. Our narrative synthesis uncovered a number of ethical, social, and cultural issues that are associated with genetic services in LMICs, with implications for implementation and delivery of such services. On the ethical side, the study revealed that genetic counseling in LMICs is often paternalistic, potentially threatening patient autonomy. Also, communication of genetic health information can have serious psychosocial consequences for the patient, and it is unclear if the appropriate supports are in place to support patient psychological wellbeing. In terms of social issues, genetics education of medical professionals is limited, and patients face difficulty accessing genetic services. Furthermore, uptake and understanding of genetic risks are affected by social determinants, and individuals face social stigma related to having a genetic disease. Regarding culture, religion and local customs may pose barriers to uptake of genetic services and understanding of results, while family structure and unity may become threatened by communication of genetic testing results.

The World Health Organization (WHO) provides some guidance on the implementation of community genetic services in LMICs to prevent congenital disorders and genetic diseases.183 Our findings were consistent with several issues outlined in the WHO report, such as financial barriers that limit access to genetic services, legal restrictions surrounding abortion, inadequacy of medical training in clinical genetics, stigmatization of individuals with genetic disease, and lack of standardization or practice guidelines for genetic testing.183 While the WHO report emphasizes the need to sensitize health professionals, public policy makers, and general public to these issues, there are no additional recommendations for how to address these issues.

The social ecological model may be one way to surpass the limitations of the WHO report and provide a practical way forward in implementing genetic services in LMICs. The social ecological model is a theory-based framework that recognizes the dynamic interrelation of an individual’s health and wellbeing with their greater environmental, social, and cultural context.39,40 Our use of the social ecological model to frame the issues identified in this study revealed how future recommendations for policy and practice can maximize the potential for service improvement, namely by targeting multiple levels of influence (Fig. 3). For example, on the public policy level, introducing medical practice guidelines for both genetic testing and counseling could change clinical practice (institutional level), including the issue of directive counseling within the patient–clinician relationship (interpersonal level). Additionally, policy changes to government health insurance schemes to include coverage of genetic testing could tackle the financial barriers associated with accessing genetic services. Admittedly, LMICs may contend with various political, social, or economic barriers that may make this difficult or a lower priority.

At the community level, public health advocacy and awareness could increase the general public’s acknowledgement of genetic services as both valuable and beneficial. Community health workers (CHWs) could be involved advocacy and other aspects of genetic health service delivery. In many LMICs, CHWs have been shown to be cost-effective in facilitating healthcare access and utilization for populations in resource-limited areas.184 CHWs have improved disease prevention and long-term screening for noncommunicable diseases.185 In India, the establishment of a community genetic outreach worker to raise awareness of autosomal recessive disorders associated with consanguinity, support affected individuals, identify families at risk, and increase uptake of local genetic services demonstrated a successful and sustainable community-based genetic service model.186

At the institutional level, effective coordination and referral between psychosocial services and genetic counseling could help support individuals and families in coping with disease. Increasing awareness for genetic testing at the institutional level could increase demand and thus streamline operating costs of laboratories. It is imperative also to identify in which LMICs formal medical genetics and genetic counseling programs are offered, to help address training gaps, potentially through international collaboration. Additionally, inclusion of more genetics education into the curriculum of medical professional training can improve clinician awareness and competency when dealing with genetic diseases (improving care on the interpersonal level). Specialized training could assist in dispelling myths and stigma surrounding genetic diseases.

The effects of a genetic diagnosis extend beyond the individual concerned and affect their interpersonal sphere. Western models of individual informed consent have been challenged in some LMICs; for instance, in India, the ethical guideline in health research states that the entire family must give permission for a woman to participate in a study.187 A study on Asian and Pacific Islander culture describes decision-making as a family-oriented and shared process, where physicians have adapted their communication approach to ensure that all family members receive equivalent health information.188 These interpersonal models of counseling may be key to eliminating stigma and family conflict that are commonly reported consequences of a positive genetic diagnosis.

One potential limitation of this study is that the issues uncovered may be representative of individuals from a higher socioeconomic status, given that they are likeliest to access genetic services in the first place. Furthermore, by limiting the review to English language studies published in peer-reviewed journals, we may have missed important insights from non-English language or gray literature. A major strength of our study is the diverse collection of articles and methodologies it referenced, which facilitated capture of ethical, social, and cultural factors from a variety of perspectives (e.g., patient, health provider, etc.). It is also relevant to note that the issues identified in our review may not be exclusively relevant to LMICs; our End-User Committee highlighted that human experiences of genetic services can be universal and, in their experience, the issues identified in this review are also relevant in HICs, where clinical genetic services have become the standard care. Finally, the fact that the majority of studies uncovered by our systematic review were quantitative in nature suggests that the literature falls short of adequately addressing the psychosocial and behavioral issues that could influence implementation and uptake of genetic services. This is a challenge that could be overcome by conducting more qualitative studies to explore knowledge gaps.

In summary, our study is an important first step toward informing the development of evidence-based, ethical, and culturally appropriate genetic services in LMICs. As genetic testing and counseling become the norm in LMICs, it will become necessary to prioritize ethical, social, and cultural issues of genetic services alongside scientific and technological development to ensure patients with genetic disorders in LMICs receive the highest quality of clinical care.

References

Tindana P, Bull S, Amenga-Etego L, et al. Seeking consent to genetic and genomic research in a rural Ghanaian setting: a qualitative study of the MalariaGEN experience. BMC Med Ethics. 2012;13:15.

de Vries J, Bull SJ, Doumbo O, et al. Ethical issues in human genomics research in developing countries. BMC Med Ethics. 2011;12:5.

de Vries J, Jallow M, Williams TN, et al. Investigating the potential for ethnic group harm in collaborative genomics research in Africa: is ethnic stigmatisation likely? Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:1400–7.

de Vries J, Pepper M. Genomic sovereignty and the African promise: mining the African genome for the benefit of Africa. J Med Ethics. 2012;38:474–8.

de Vries J, Slabbert M, Pepper MS. Ethical, legal and social issues in the context of the planning stages of the Southern African Human Genome Programme. Med Law. 2012;31:119–52.

Jenkins T. Ethics and the Human Genome Diversity Project: an African perspective. Polit Life Sci. 1999;18:308–11.

GeneReviews®. Margaret P Adam, Editor-in-Chief; Senior Editors: Holly H Ardinger, Roberta A Pagon, and Stephanie E Wallace. Molecular Genetics: Lora JH Bean and Karen Stephens. Anne Amemiya, Genetic Counseling.Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2018.ISSN: 2372-0697 Available at: http://genetests.org

Wonkam A, Muna W, Ramesar R, et al. Capacity-building in human genetics for developing countries: initiatives and perspectives in sub-Saharan Africa. Public Health Genomics. 2010;13:492–4.

Horovitz DDG, de Faria Ferraz VE, Dain S, Marques-de-Faria AP. Genetic services and testing in Brazil. J Community Genet. 2013;4:355–75.

Nivoloni K, de AB, da Silva-Costa SM, et al. Newborn hearing screening and genetic testing in 8974 Brazilian neonates. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:926–9.

Vieira TP, Sgardioli IC, Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL. Genetics and public health: the experience of a reference center for diagnosis of 22q11.2 deletion in Brazil and suggestions for implementing genetic testing. J Community Genet. 2013;4:99–106.

Human Genomics in Global Health. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/genomics/en/. Accessed August 4, 2016.

Joseph B, Shanmugam M, Srinivasan M, Kumaramanickavel G. Retinoblastoma: genetic testing versus conventional clinical screening in India. J Mol Diagn. 2004;8:237–43.

Kucheria K, Jobanputra V, Talwar R, et al Human molecular cytogenetics: diagnosis, prognosis, and disease management. Teratog Carcinog Mutagen 2003: 225–33.

Huang Q, Dryja T, Yandell D. Gene diagnosis and genetic counselling of Rb gene mutations in retinoblastoma patients and their family members. Zhonghua Yi Xue Yi Chuan Xue Za Zhi. 1998;15:65–8.

Joseph B, Madhavan J, Mamatha G, et al. Retinoblastoma: a diagnostic model for India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:485–8.

Parsam V, Kannabiran C, Honavar S, et al. A comprehensive, sensitive and economical approach for the detection of mutations in the RB1 gene in retinoblastoma. J Genet. 2009;88:517–27.

Ramprasad V, Madhavan J, Murugan S, et al. Retinoblastoma in India: microsatellite analysis and its application in genetic counseling. Mol Diagn Ther. 2007;11:63–70.

Wonkam A, Tekendo C, Sama D, et al. Initiation of a medical genetics service in sub-Saharan Africa: experience of prenatal diagnosis in Cameroon. Eur J Med Genet. 2011;54:e399–404.

Chaabouni H, Chaabouni M, Maazoul F, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of chromosome disorders in Tunisian population. Ann Genet. 2001;44:99–104.

Dimaras H, Dimba E, Gallie B. Challenging the global retinoblastoma survival disparity through a collaborative research effort. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94:1415–6.

Hill JA, Kimani K, White A, Barasa F, Livingstone M, Gallie BL, Dimaras H; Daisy’s Eye Cancer Fund & The Kenyan National Retinoblastoma Strategy Group. Achieving optimal cancer outcomes in East Africa through multidisciplinary partnership: a case study of the Kenyan National Retinoblastoma Strategy group. Global Health 2016 May 26;12:23.

Carroll J, Rideout A, Wilson B, et al. Genetic education for primary care providers: improving attitudes, knowledge, and confidence. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:e92–99.

Dumont-Driscoll M. Genetics and the general pediatrician: where do we belong in this exploding field of medicine? Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2002;32:6–28.

Holtzman NA. Primary care physicians as providers of frontline genetic services. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1993;8:213–9.

Masum H, Singer PA. A visual dashboard for moving health technologies from ‘lab to village’. J Med Internet Res. 2007;9:e32.

Kingsmore SF, Lantos JD, Dinwiddie DL, et al. Next-generation community genetics for low- and middle-income countries. Genome Med. 2012;4:25.

Melo DG, Sequeiros J. The challenges of incorporating genetic testing in the Unified National Health System in Brazil. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16:651–5.

Wonkam A, Njamnshi AK, Mbanya D, et al. Acceptability of prenatal diagnosis by a sample of parents of sickle cell anemia patients in Cameroon (sub-Saharan Africa). J Genet Couns. 2011;20:476–85.

Tschudin S, Huang D, Mor-Gültekin H. Prenatal counseling–implications of the cultural background of pregnant women on information processing, emotional response and acceptance. Eur J Ultrasound. 2011;32:e100–107.

Jegede AS. Culture and genetic screening in Africa. Dev World Bioeth. 2009;9:128–37.

Ghosh K, Shetty S, Pawar A, Mohanty D. Carrier detection and prenatal diagnosis in haemophilia in India: realities and challenges. Haemophilia. 2002;8:51–5.

Zhong A, Darren B, Dimaras H. Ethical, social, and cultural issues related to clinical genetic testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:140.

World Bank. Low and middle income. 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/income-level/low-and-middle-income?view=chart. Accessed May 20, 2016.

World Bank. High income. 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/income-level/high-income?view=chart. Accessed May 20, 2016.

World Bank. Taiwan, China. 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/country/taiwan-china. Accessed May 20, 2016.

Kmet L, Lee R, Cook L Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. 2004. https://www.ihe.ca/publications/standard-quality-assessment-criteria-for-evaluating-primary-research-papers-from-a-variety-of-fields. Accessed May 21, 2018.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme. 2006. http://www.lancs.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications/NS_Synthesis_Guidance_v1.pdfaccessdate?

McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Behav. 1988;15:351–77.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The social-ecological model: a framework for prevention. 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/crccp/sem.html. Accessed July 16, 2017.

Carnevale A, Villa AR, Armendares S. Attitudes of Mexican geneticists towards prenatal diagnosis and selective abortion. Am J Med Genet. 1998;431:426–31.

Carnevale A, Lisker R, Villa AR, et al. Counselling following diagnosis of a fetal abnormality: comparison of different clinical specialists in Mexico. Am J Med Genet. 1997;28:23–8.

Ataman E, Cogulu O, Durmaz A, et al. The rate of sex chromosome aneuploidies in prenatal diagnosis and subsequent decisions in Western Turkey. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2012;16:150–3.

Christianson MA, Christianson AL. South African geneticists’ attitudes to the present Abortion and Sterilisation Act of 1975. South Afr Med J. 1996;86:534–6.

Balkan M, Kalkanli S, Akbas H, et al. Parental decisions regarding a prenatally detected fetal chromosomal abnormality and the impact of genetic counseling: an analysis of 38 cases with aneuploidy in Southeast Turkey. J Genet Couns. 2010;19:241–6.

Gupta JA. Exploring Indian women’s reproductive decision-making regarding prenatal testing. Cult Health Sex. 2010;2:37–41.

Eldahdah L, Ormond K, Nassar A, et al. Outcome of chromosomally abnormal pregnancies in Lebanon: obstetricians’ roles during and after prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:525–34.

Gupta JA. Private and public eugenics: genetic testing and screening in India. J Bioeth Inq. 2007;4:217–28.

Guilam MCR, Corrêa MCDV. Risk, medicine and women: a case study on prenatal genetic counseling in Brazil. Dev World Bioeth. 2007;7:78–85.

Lisker R, Carnevale A. Changing opinions of Mexican geneticists on ethical issues. Arch Med Res. 2006;37:794–803.

Solomon G, Greenberg J, Futter M, et al. Understanding of genetic inheritance among Xhosa-speaking caretakers of children with hemophilia. J Genet Couns. 2012;21:726–40.

Wertz DC, Fletcher JC, Wertz DC, Fletcher JC. Ethical and social issues in prenatal sex selection: a survey of geneticists in 37 nations. Soc Sci Med. 1998;46:255–73.

Yanikkerem E, Ay S, Alev YC. A survey of the awareness, use and attitudes of women towards Down syndrome screening. J Clin Nurs. 2012;22:1748–58.

Sui S. The practice of genetic counselling—a comparative approach to understanding genetic counselling in China. Biosocieties. 2009;4:391–405.

Lisker R, Carnevale A, Armendares S. Mexican geneticists’ views of ethical issues in genetics testing and screening. Are eugenic principles involved? Clin Genet. 1999;56:323–7.

Mao X, Wertz DC. China’s genetic services providers’ attitudes towards several ethical issues: a cross-cultural survey. Clin Genet. 1997;52:100–9.

Sleeboom-Faulkner ME. Genetic testing, governance, and the family in the People’s Republic of China. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1802–9.

Wertz DC. Eugenics is alive and well: a survey of genetic professionals around the world. Sci Context. 2014;11:493–510.

Bruwer Z, Futter M, Ramesar R. Communicating cancer risk within an African context: experiences, disclosure patterns and uptake rates following genetic testing for Lynch syndrome. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:53–60.

Karimi M, Bonyadi M, Galehdari M, Zareifar S. Termination of pregnancy due to thalassemia major, hemophilia, and Down’s syndrome: the views of Iranian physicians. BMC Med Ethics. 2008;9:8–11.

Su B, Macer DR. Chinese people’s attitudes towards genetic diseases and children with handicaps. Law Hum Genome Rev. 2003;18:191–210.

Todd C, Haw T, Kromberg J, Christianson A. Genetic counseling for fetal abnormalities in a South African community. J Genet Couns. 2010;19:247–54.

Simpson B, Dissanayake VHW, Wickramasinghe D, Jayasekara RW. Prenatal testing and pregnancy termination in Sri Lanka: views of medical. Ceylon Med J. 2003;48:129–32.

Wonkam A, Angwafo F. Prenatal diagnosis may represent a point of entry of genetic science in sub-Saharan Africa: a survey on the attitudes of medical students and physicians from Cameroon. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26:760–1.

Hall S, Chitty L, Dormandy E, et al. Undergoing prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome: presentation of choice and information in Europe and Asia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:563–9.

Van den Heuvel A,Hollywood A,Hogg J, et al. Informed choice to undergo prenatal screening for thalassemia: a description of written information given to pregnant women in Europe and beyond. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:727–34.

de Villiers C, Weskamp K, Bryer A. The sword of Damocles: the psychosocial impact of familial spinocerebellar ataxia in South Africa. Am J Med Genet. 1997;74:270–4.

Ghanei M, Adibi P, Movahedi M, et al. Pre-marriage prevention of thalassaemia: report of a 100,000 case experience in Isfahan. Public Health. 1997;111:153–6.

Usta IM, Nassar AH, Abu-musa AA, Hannoun A. Effect of religion on the attitude of primiparous women toward genetic testing. Prenat Diagn. 2010;30:241–6.

Correia PS, Vitiello P. Conceptions on genetics in a group of college students. J Community Genet. 2013;4:115–23.

Karimi M, Peyvandi F, Siboni S, et al. Comparison of attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy for haemophilia in Iran and Italy. Haemophilia. 2004;10:367–9.

Haghpanah S, Nasirabadi S, Rahimi N, et al. Sociocultural challenges of beta-thalassaemia major birth in carriers of beta-thalassaemia in Iran. J Med Screen. 2012;19:109–11.

Dinc L. The psychological impact of genetic testing on parents. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:45–51.

Pattanayak RD, Sagar R. A qualitative study of perceptions related to family risk of bipolar disorder among patients and family members from India. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2011;58:463–9.

Mudiyanse RM. Thalassemia treatment and prevention in Uva province, Sri Lanka: a public opinion survey. Hemoglobin. 2006;30:275–89.

Paneque M, Lemos C, Escalona K, et al. Psychological follow-up of presymptomatic genetic testing for spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 (SCA2) in Cuba. J Genet Couns. 2007;16:469–79.

Paneque HM, Prieto AL, Reynaldo RR, et al. Psychological aspects of presymptomatic diagnosis of spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 in Cuba. Community Genet. 2007;10:132–9.

Ross PT, Lypson ML, Ursu DC, et al. Attitudes of Ghanaian women toward genetic testing for sickle cell trait. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;115:264–8.

Paneque M, Lemos C, Sousa A. Role of the disease in the psychological impact of pre-symptomatic testing for SCA2 and FAP ATTRV30M: experience with the disease, kinship and gender of the transmitting parent. J Genet Couns. 2009;18:483–93.

Pandey G, Panigrahi I, Phadke S, Mittal B. Knowledge and attitudes towards haemophilia: the family side and role of haemophilia societies. Community Genet. 2003;6:120–2.

Sangani B, Sukumaran PK, Mahadik C, et al. Thalassaemia in Bombay: the role of medical genetics in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:75–81.

Wong AE, Kuppermann M, Creasman JM, et al. Patient and provider attitudes toward screening for Down syndrome in a Latin American country where abortion is illegal. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2011;115:235–9.

Futter M, Heckmann J, Greenberg L. Predictive testing for Huntington disease in a developing country. Clin Genet. 2009;75:92–7.

Basu D, Pettifor JM, Kromberg J. X-linked hypophosphataemia in South Africa. South Afr Med J. 2004;94:460–4.

Canatan D, Ratip S, Kaptan S. Psychosocial burden of b-thalassaemia major in Antalya, South Turkey. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56:815–9.

Phadke SR, Agarwal SS. Adverse effects of genetic counselling on women carriers of disease: the Indian perspective. Natl Med J India. 2001;14:47–9.

Mariño TC, Armiñán RR, Cedeño HJ, et al. Ethical dilemmas in genetic testing: examples from the Cuban Program for Predictive Diagnosis of Hereditary Ataxias. J Genet Couns. 2011;20:241–8.

Jain S, Muthane UB, Nagaraja SM. Perspectives towards predictive testing in Huntington disease. Neurol India 2006;54:359–62.

Zahed L, Bou-Dames J. Acceptance of first-trimester prenatal diagnosis for the haemoglobinopathies in Lebanon. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:423–8.

Romero-Hidalgo S, Urraca N, Parra D, et al. Attitudes and anticipated reactions to genetic testing for cancer among patients in Mexico City. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2009;13:477–83.

Sui S, Sleeboom-Faulkner M. Choosing offspring: prenatal genetic testing for thalassaemia and the production of a ‘saviour sibling’ in China. Cult Health Sex. 2010;12:167–75.

Wong LP, George E, Tan JMA. Public perceptions and attitudes toward thalassaemia: influencing factors in a multi-racial population. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:193.

Erwene CM, Pacheco JCG. Effectiveness of genetic counselling. Ophthalmic Paediatr Genet. 1991;12:85–91.

Dorticos-Balea A, Martin-Ruiz M, Hechevarria-Fernandez P, et al. Reproductive behaviour of couples at risk for sickle cell disease in Cuba: a follow-up study. Prenat Diagn. 1997;18:737–42.

Palmero E, Kalakun L, Schuler-Faccini L, et al. Cancer genetic counseling in public health care hospitals: the experience. Community Genet. 2007;10:110–9.

Yilmaz Z, Sahin F, Bulakbasi T, et al. Ethical considerations regarding parental decisions for termination following prenatal diagnosis of sex chromosome abnormalities. Genet Couns. 2008;19:345–52.

Zahed L, Nabulsi M, Usta I. Acceptance of prenatal diagnosis for genetic disorders in Lebanon. Prenat Diagn. 1999;19:1109–12.

Zhang W, Gao Y, Li Q, Xu D. Breast cancer in China: demand for genetic counseling and genetic testing. Genet Med. 2006;8:196–7.

Cousens NE, Gaff CL, Metcalfe SA, Delatycki MB. Carrier screening for beta-thalassaemia: a review of international practice. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1077–83.

Tomatır G, Ozsahin A, Sorkun H, et al. Midwives’ approach to genetic diseases and genetic counseling in Denizli, Turkey. J Genet Couns. 2006;15:191–8.

Rim PHH, Magna LA, Ramalho AS. Genetics and prevention of blindness. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2006;69:481–5.

Lim F, Downs J, Li J, et al. Barriers to diagnosis of a rare neurological disorder in China—lived experiences of Rett syndrome families. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:1–9.

Saxena A, Phadke S. Thalassaemia control by carrier screening: the Indian scenario. Curr Sci. 2002;83:291–5.

Ghasemi N, Ayatolahi J, Mosaddegh M. Assessment of knowledge and attitude of medical student toward genetic counselling and therapeutic abortion. J Med Sci. 2007;7:810–5.

Jha CB, Jha N, Bhattacharya S, et al. D. Knowledge about human genetics among school students of Eastern Nepal. J Nepal Med Assoc. 2007;46:90–2.

Gharaibeh H, Oweis A, Hamad KH. Nurses’ and midwives’ knowledge and perceptions of their role in genetic teaching. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57:435–42.

Dhasaradan I, Shanmugam RS. Nurses’ knowledge about genetics. Nurs J India. 2005;96:249–51.

Vural BK, Tomatir AG, Kurban NK, Taspinar A. Nursing students’ self-reported knowledge of genetics and genetic education. Public Health Genomics. 2009;12:225–32.

Oloyede OAO. Down syndrome screening in Nigeria. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;100:88–9.

Terzioglu F, Dinç L. Nurses’ views on their role in genetics. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2002;33:756–64.

Vilatela M, Morales A, de la Cadena CG, et al. Predictive and prenatal diagnosis of Huntington’s disease: attitudes of Mexican neurologists, psychiatrists, and psychologists. Arch Med Res. 1999;30:320–4.

Wonkam A, Njamnshi AK, Angwafo FF. Knowledge and attitudes concerning medical genetics amongst physicians and medical students in Cameroon (sub-Saharan Africa). Genet Med. 2006;8:331–8.

Dave U, Shetty N, Mehta L. A community genetics approach to population screening in India for mental retardation—a model for developing countries. Ann Hum Biol. 2005;32:195–203.

Adeyemo O, Omidiji O, Shabi O. Level of awareness of genetic counselling in Lagos, Nigeria: its advocacy on the inheritance of sickle cell disease. Afr J Biotechnol. 2007;6:2758–65.

Dissanayake VHW, Simpson R, Jayasekara RW Attitudes towards the new genetic and assisted reproductive technologies in Sri Lanka: a preliminary report. New Genet Soc. 2002;21:65–74.

Chen Y, Banta HD, Wang Q. Situation analysis of prenatal diagnosis technology utilization in China: current situation, main issues, and policy implications. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;4:524–30.

Rodrigues C, de Oliveria V, Camargo G, et al. Presymptomatic testing for neurogenetic diseases in Brazil: assessing who seeks and who follows through with testing. J Genet Couns. 2012;21:101–12.

Simpson B. On parrots and thorns: Sri Lankan perspective on genetics, science and personhood. Health Care Anal. 2007;15:41–9.

Sui S, Sleeboom-Faulkner M. Commercial genetic testing in mainland China: social, financial and ethical issues. J Bioeth Inq. 2007;4:229–37.

Monlleo IL, Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL. Brazil’s Craniofacial Project: genetic evaluation and counseling in the Reference Network for Craniofacial Treatment. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2004;43:29–31.

Achatz W, Isabel M, Hainaut P, et al. Highly prevalent TP53 mutation predisposing to many cancers in the Brazilian population: a case for newborn screening? Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:920–5.

Van Den Heuvel A, Chitty L, Dormandy E, et al. Is informed choice in prenatal testing universally valued? A population-based survey in Europe and Asia. BJOG. 2009;116:880–5.

Van Den Heuvel A, Chitty L, Dormandy E, et al. Informed choice in prenatal testing: a survey among obstetricians and gynaecologists in Europe and Asia. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:1238–44.

Tomatir A, Sorkun H, Demirhan H, Akdag B. Genetics and genetic counseling: practices and opinions of primary care physicians in Turkey. Genet Med. 2007;9:130–5.

Abu-musa AA, Nassar AH, Usta IM. Attitude of women with IVF and spontaneous pregnancies towards prenatal screening. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:2438–43.

Baxi A, Manila K, Kadhi P. Carrier screening for b thalassemia in pregnant Indian women: experience at a single center in Madhya Pradesh. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2013;29:71–4.

Baig SM, Azhar A, Hassan H, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of β-thalassemia in Southern Punjab, Pakistan. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26:903–5.

Karimi M, Johari S, Cohan N. Attitude toward prenatal diagnosis for b-thalassemia major and medical abortion in southern Iran. Hemoglobin. 2010;34:49–54.

Keskin A, Turk R, Polat A, et al. Premarital screening of beta-thalassemia trait in the province of Denizli, Turkey. Acta Haematol. 2000;104:31–3.

Khorasani G, Kosaryan M, Vahidshahi K, et al. Results of the national program for prevention of beta-thalassemia major in the Iranian province of Mazandaran. Hemoglobin. 2008;32:263–71.

Gharaibeh H, Mater FK. Young Syrian adults’ knowledge, perceptions and attitudes to premarital testing. Int Nurs Rev. 2009;56:450–5.

Nahar R, Puri RD, Saxena R, Verma IC. Do parental perceptions and motivations towards genetic testing and prenatal diagnosis for deafness vary in different cultures? Am J Med Genet. 2013;161A:76–81.

Naseem S, Ahmed S, Vahidy F. Impediments to prenatal diagnosis for beta thalassaemia: experiences from Pakistan. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:1116–8.

Wong LP, George E, Tan JMA. A holistic approach to education programs in thalassemia for a multi-ethnic population: consideration of perspectives, attitudes, and perceived needs. J Community Genet. 2011;2:71–9.

Ahmadnezhad E, Sepehrvand N, Jahani F, et al. Evaluation and cost analysis of national health policy of thalassaemia screening in West-Azerbaijan Province of Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:687–92.

Ahmed S, Saleem M, Sultana N, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of beta-thalassaemia in Pakistan: experience in a Muslim country. Prenat Diagn. 2000;20:378–83.

Balgir R. Birth control necessary to limit family size in tribal couples with aberrant heterosis of G-6-PD deficiency and sickle cell disorders in India: an urgency of creating awareness and imparting genetic counseling. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:357–62.

Mao X. Chinese geneticists’ views of ethical issues in genetic testing and screening: evidence for eugenics in China. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:688–95.

Penn C, Watermeyer J, Macdonald C, Moabelo C. Grandmothers as gems of genetic wisdom: exploring South African traditional beliefs about the causes of childhood genetic disorders. J Genet Couns. 2010;19:9–21.

Ndjapa-Ndamkou C, Govender L, Moodley J. Views and attitudes of pregnancy women regarding late termination of pregnancy for severe fetal abnormalities at a tertiary hospital in KwaZulu Natal. S Afr J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;19:49–52.

Alsulaiman A, Hewison J. Attitudes to prenatal and preimplantation diagnosis in Saudi parents at genetic risk. Prenat Diagn. 2006;26:1010–4.

Pruksanusak N, Suwanrath C, Kor-anantakul O. A survey of the knowledge and attitudes of pregnant Thai women towards Down syndrome screening. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:876–81.

Paz-Y-Mino C, Sanchez ME, Sarmiento I, Leone PE. Genetics and congenital malformations: interpretations, attitudes and practices in Ecuador. Community Genet. 2006;9:268–73.

Yoon S, Thong M, Taib N, et al. Genetic counseling for patients and families with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer in a developing Asian country: an observational descriptive study. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:199–205.

Phadke SR, Pandey A, Puri RD, Patil SJ. Genetic counseling: the impact in Indian milieu. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:1079–82.

Rahaman S, Abd E, Mohamed G, Al B. Prenatal diagnosis in low resource setting: is it acceptable? J Obstet Gynecol India. 2012;62:515–9.

Balgir R. Intervention and prevention of hereditary hemolytic disorders in India: a case study of two ethnic communities of Sundargarh District in Orissa. J Assoc Physicians India. 2008;56:851–8.

Arif MO, Fatmi Z, Pardeep B, et al. Attitudes and perceptions about prenatal diagnosis and induced abortion among adults of Pakistani population. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:1149–55.

Kesari A, Rennert H, Leonard DGB, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy: Indian scenario. Prenat Diagn. 2005;25:641–4.

Neghina AM, Anghel A. Hereditary hemochromatosis: awareness and genetic testing acceptability in Western Romania. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:847–50.

Bryant LD, Ahmed S, Ahmed M, et al. ‘All is done by Allah.’ Understandings of Down syndrome and prenatal testing in Pakistan. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1393–9.

Awwad R, Veach PM, Bartels DM, Leroy BS. Culture and acculturation influences on Palestinian perceptions of prenatal genetic counseling. J Genet Couns. 2008;17:101–16.

Cruz-Marino T, Velazquoz-Perez L, Gonzalez-Zaldivar Y, et al. The Cuban program for predictive testing of SCA2: 11 years and 768 individuals to learn from. Clin Genet. 2013;83:518–24.

Ghotbi N, Tsukatani T. Evaluation of the national health policy of thalassaemia screening in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11:308–18.

Gibbon S. Family medicine, ‘La Herencia’ and breast cancer; understanding the (dis)continuities of predictive genetics in Cuba. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:1784–92.

Widayanti CG, Ediati A, Tamam M, et al. Feasibility of preconception screening for thalassaemia in Indonesia: exploring the opinion of Javanese mothers. Ethn Health. 2011;16:483–99.

Gilani AI, Jadoon AS, Qaiser R, et al. Attitudes towards genetic diagnosis in Pakistan: a survey of medical and legal communities and parents of thalassemic children. Community Genet. 2007;10:140–6.

Habibzadeh F, Yadollahie M, Roshanipoor M, Haghshenas M. Reproductive behaviour of mothers of children with beta-thalassaemia major. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18:246.

Fullwiley D. Discriminate biopower and everyday biopolitics: views on sickle cell testing in Dakar. Med Anthropol. 2004;2:157–94.

Meilleur KG, Coulibaly S, Traoré M. Genetic testing and counseling for hereditary neurological diseases in Mali. J Community Genet. 2011;2:33–42.

Das K, Mohanty D. Genetic counseling in tribals in India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:561.

Yagnik H. Post counselling follow-up of thalassemia in high risk communities. Indian Pediatr. 1997;34:1115–8.

Lisker R, Carnevale A, Ja V, et al. Mexican geneticists’ opinions on disclosure issues. Clin Genet. 1998;54:321–9.

Panter-Brick C. Coping with an affected birth: genetic counseling in Saudi Arabia. J Child Neurol. 1992;7:69–72.

Arif F, Fayyaz J, Hamid A. Awareness among parents of children with thalassemia major. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:621–4.

Sahin NH, Gungor I. Congenital anomalies: parents’ anxiety and women’s concerns before prenatal testing and women’s opinions towards the risk factors. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:827–36.

Durosinmi MA, Hospital RM. Acceptability of prenatal diagnosis of sickle cell anemia (SCA) by female patients and parents of SCA in Nigeria. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41:433–6.

Chattopadhyay S. ‘Rakter dosh’—corrupting blood: the challenges of preventing thalassemia in Bengal, India. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63:2661–73.

Alkuraya FS, Kilani RA. Attitude of Saudi families affected with hemoglobinopathies towards prenatal screening and abortion and the influence of religious ruling (fatwa). Prenat Diagn. 2001;21:448–51.

De Silva DC, Jayawardana P, Hapangama A, et al. Attitudes toward prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy for genetic disorders among healthcare workers in a selected setting in Sri Lanka. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:715–21.

Scott CJ, Futter M, Wonkam A. Prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy: perspectives of South African parents of children with Down syndrome. J Community Genet. 2013;4:87–97.

Jafri H, Ahmed S, Ahmed M, et al. Islam and termination of pregnancy for genetic conditions in Pakistan: implications for Pakistani health care providers. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:1218–20.

El-Beshlawy A, El-Shekha A, Momtaz M, et al. Prenatal diagnosis for thalassaemia in Egypt: what changed parents’ attitude? Prenat Diagn. 2012;32:777–82.

Alsulaiman A, Hewison J. Attitudes to prenatal testing and termination of pregnancy in Saudi Arabia. Community Genet. 2007;10:169–73.

Afolayan JA, State K, Jolayemi FT. Parental attitude to children with sickle cell disease in selected health facilities in Irepodun Local Government, Kwara State, Nigeria. Stud Ethno-Med. 2011;5:33–40.

Moronkola OA, Fadairo RA. University students in Nigeria: knowledge, attitude toward sickle cell disease, and genetic counseling before marriage. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2007;26:85–93.

Bhardwaj M, Macer DR. Policy and ethical issues in applying medical biotechnology in developing countries. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:49–55.

Lynch HT, Aldoss I, Lynch JF. The identification and management of hereditary diffuse gastric cancer in a large Jordanian family. Fam Cancer. 2011;10:667–72.

Zounon O, Anani L, Latoundji S, et al. Misconceptions about sickle cell disease (SCD) among lay people in Benin. Prev Med. 2012;55:251–3.

Nordling L. How the genomics revolution could finally help Africa. Nature. 2017;544:20–2.

Folarin OA, Happi AN, Happi CT. Empowering African genomics for infectious disease control. Genome Biol. 2014;15:515.

H3Africa Consortium, Rotimi C, Abayomi A, et al. Research capacity. Enabling the genomic revolution in Africa. Science. 2014;344:1346–8.

World Health Organization (2011). Community genetics services : report of a WHO consultation on community genetics in low- and middle-income countries. Geneva : World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/44532

Viswanathan M, Kraschnewski JL, Nishikawa B, et al. Outcomes and costs of community health worker interventions. Med Care. 2010;48:792–808.

Kim K, Choi JS, Choi E, et al. Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:e3–28.

Khan N Community engagement and education: addressing the needs of South Asian families with genetic disorders. J Community Genet 2016;7:317-323.

Roberts LR, Jadalla A, Jones-Oyefeso V, et al. Researching in collectivist cultures. J Transcult Nurs. 2017;28:137–43.

McLaughlin LA, Braun KL. Asian and Pacific islander cultural values: considerations for health care decision making. Health Soc Work. 1998;23:116–27.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Cheri Nickel (Information Scientist; The Hospital for Sick Children) for her assistance in developing the search strategy. We also thank members of our End-User Committee who have consulted during various stages of the study: Dr. Lucy Njambi (Kenya), Dr. Pamela Astudillo (Philippines), Dr. Luciana Campi Auresco (Brazil), Dr. Jaime Jessen (Canada), Abby White (World Eye Cancer Hope, UK), and Dr. Ella Bowles (Canada). Adrina Zhong was supported by the Dr. James Rossiter MPH Practicum Award (Canadian Institute for Health Research) and Dr. Arnold Noyek Legacy Fund Award in Global Health (University of Toronto).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhong, A., Darren, B., Loiseau, B. et al. Ethical, social, and cultural issues related to clinical genetic testing and counseling in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Genet Med 23, 2270–2280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0090-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0090-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Perceptions and beliefs of community gatekeepers about genomic risk information in African cleft research

BMC Public Health (2024)

-

Community health workers in India should be trained to offer genetic counselling for rare diseases

Nature Medicine (2024)

-

Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of implementing a decision support intervention for cascade screening for beta-thalassemia in Pakistan

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)

-

Barriers to genetic testing in clinical psychiatry and ways to overcome them: from clinicians’ attitudes to sociocultural differences between patients across the globe

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

-

Cascade screening for beta-thalassemia in Pakistan: development, feasibility and acceptability of a decision support intervention for relatives

European Journal of Human Genetics (2022)