Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are small membranous vesicles secreted by multiple kinds of cells and are widely present in human body fluids. EVs containing various constituents can transfer functional molecules from donor cells to recipient cells, thereby mediating intercellular communication. Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are a type of RNA transcript with limited protein-coding capacity, that have been confirmed to be enriched in EVs in recent years. EV ncRNAs have become a hot topic because of their crucial regulating effect in disease progression, especially in cancer development. In this review, we summarized the biological functions of EV ncRNAs in the occurrence and progression of gynecological malignancies. In addition, we reviewed their potential applications in the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological malignancies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

Extracellular vesicles are small membranous vesicles containing various constituents.

-

Noncoding RNAs are functional transcripts with limited protein-coding capacity.

-

Extracellular vesicle noncoding RNAs regulate the occurrence and progression of gynecological malignancies.

-

Extracellular vesicle noncoding RNAs may be applied in the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological malignancies

Open questions

-

What are the functions of extracellular vesicle noncoding RNAs on the development of gynecological malignancies?

-

How are extracellular vesicle noncoding RNAs involved in the progression of gynecological malignancies?

-

How can we employ extracellular vesicle noncoding RNAs to monitor and treat gynecological malignancies?

Introduction

Gynecological malignancies, mainly cervical cancer (CC), ovarian cancer (OC) and endometrial cancer (EC), are a worldwide problem that seriously endanger women’s health and lives. Although progress has been made in the prevention, screening, diagnosis and treatment of these cancers over the past decades, many issues remain to be solved, such as the early diagnosis and chemoresistance of OC [1] and the recurrence and metastasis of CC [2] and EC [3].

Noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs), once considered to be transcriptional noise for not coding proteins, are classified into different categories: microRNAs (miRNAs), long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs) and other types [4]. Recently increasing evidence has shown that ncRNAs play a vital role in various physiological and pathophysiological processes via transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation. It has been reported that aberrant expression of miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs is associated with cancer progression [5, 6]. Notably, ncRNAs employ extracellular vesicles (EVs) to reach recipient cells or tissues, acting as messengers of intercellular communication [7,8,9]. EVs are small membranous vesicles with a heterogeneous bilayer phospholipid structure [10] that are produced by multiple types of cells and identified in various body fluids, such as serum, plasma, urine, saliva, ascites, pleural fluid, and breast milk. EVs contain abundant bioactive components, including proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNA, ncRNAs and metabolites [11, 12], and mediate intercellular communication by transferring these molecules from donor cells to recipient cells to perform numerous functions [13]. Accumulating evidence indicates that EV ncRNAs are widely involved in cancer occurrence, progression, metastasis and chemoresistance [7, 8, 14]. In this review, we summarized the current studies about EV ncRNAs and their emerging roles in affecting the processes of gynecological malignancies. EV miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs were discussed, highlighting the major contribution of EV miRNAs and lncRNAs to CC and OC. In addition, we investigated their potential applications in the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological malignancies, providing new insights into the development of biomarkers and anticancer therapy.

The functional roles of ncRNAs in gynecological malignancies

ncRNAs are functional transcripts with limited protein-coding capacity, that can be divided into different classes, mainly according to their length. Here, we primarily focused on miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs and briefly discussed their roles in regulating gynecological malignancy progression.

miRNAs are short ncRNAs of ~22 nucleotides (nt) in length that regulate the expression of mRNAs. miRNAs degrade mRNA or repress their translation by binding to their 3’ untranslated regions (3’ UTRs) with complementary sequences [15]. Ultimately, miRNAs seem to function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors in cancer, including gynecological malignancies. For instance, MIR-G-1, acting as an oncogene in CC, can activate the WNT-CTNNB1/β-catenin signaling pathway by interacting with WNT7B, thereby upregulating TMED5 to promote cell proliferation, migration, invasion and tumor growth [16]. These oncogenic miRNAs have the potential to serve as targets in anticancer therapy. However, in OC, miR-450a reduced tumor migration, invasion and growth in vivo and in vitro, by modulating energetic metabolism and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), suggesting that it functions as a tumor suppressor [17]. Many studies suggest that these suppressive miRNAs are downregulated in cancers, such as CC, OC and EC.

ncRNAs greater than 200 nt in length are defined as lncRNAs. Unlike miRNAs, lncRNAs function in multifarious ways. It was reported that lncRNAs can not only bind to proteins but can also interact with mRNAs, miRNAs and DNA, exhibiting diverse mechanisms. However, it was reported that most lncRNAs in gynecological malignancies function by interacting with proteins or miRNAs. A multitude of lncRNAs, such as HOTAIR, H19, MALAT1, MEG3, LET and PVT1, are correlated with cancer development. Zhang et al. reported that MEG3 can directly bind to the P-STAT3 protein and promote the degradation of P-STAT3 via ubiquitination [18]. The instability of P-STAT3 further inhibits the proliferation and promotes the apoptosis of CC cells [18]. In addition, lncRNAs often act as sponges or competitive endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs) for miRNAs to prevent gene repression mediated by miRNA. For example, it was reported that HOTAIR, acting as an oncogenic molecular, is upregulated in CC. Li et al. reported that HOTAIR can competitively bind to miR-23b and regulate the expression of MAPK1, promoting the proliferation and invasion of CC cells [19]. Furthermore, lncRNAs can also act as scaffolds. Like lnc-CCDST in CC, lnc-CCDST can promote DHX9 degradation by providing a scaffold for the formation of DHX9 and MDM2 complexes. DHX9 degradation inhibits the migration and invasion of cancer cells [20]. Above all, lncRNAs can function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors via various regulatory mechanisms.

circRNAs are a special type of lncRNA with a single-stranded covalently closed RNA structure. Several circRNAs were aberrantly expressed in gynecological malignancies. It seems that circRNAs function similarly to lncRNA by serving as sponges of miRNA and scaffolds for proteins and regulating transcription and splicing. However, it was reported that most circRNAs in gynecological malignancies regulate protein expression by sponging miRNAs, as observed with circ101996 [21], circATP8A2 [22], circ0007534 [23] and circ0075341 [24] in CC and circEPSTI1 [25], circ0061140 [26], circWHSC1 [27] and circCELSR1 [28] in OC. Similarly, circRNAs can also promote or inhibit cancer development via these diverse mechanisms.

Although the three kinds of ncRNAs mentioned above were initially regarded as lacking protein-coding abilities, an increasing number of studies have revealed that some of them carrying small open reading frames can be translated into peptides or proteins [29]. The lncRNA HOXB-AS can be translated into a conserved 53-aa peptide, which inhibits colon cancer growth by suppressing glucose metabolism [30]. It has been reported that LINC-PINT [31], circRNA-SHPRH [32], FBXW7 [33] and AKT3 [34] can encode small peptides that suppresses tumorigenesis in certain cancers. In contrast, small peptides encoded by circPPP1R12A [35], LINC00998 [36] and LOC90024 [37] can promote cancer development. In addition, Kang et al. identified a small peptide, miPEP133, encoded by pri-miRNA miR-34a, which was highly expressed in the ovary and other tissues. Additionally, miPEP133 inhibited the migration and invasion of cancer cells [38]. These results suggest that small peptides encoded by ncRNAs are correlated with cancer progression. More functional small peptides are being discovered in gynecological malignancies.

The biogenesis and characteristics of EVs

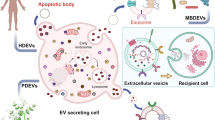

EVs can be divided into three types, mainly exosomes, microvesicles (MVs, also called ectosomes), and apoptotic bodies, on the basis of their biogenesis or cellular origin [39]. In consideration that apoptotic bodies are derived from the membranes of apoptotic cells, we primarily focused on exosomes and microvesicles. MVs are membranous vesicles 50–1000 nm in diameter that can be immediately released by direct budding from the plasma membrane [39]. However, exosomes, which are ~30–150 nm in diameter, have drawn increasing attention due to their unique characteristics. Exosomes are generated through a series of processes involving the formation of intracellular multivesicular bodies (MVBs) and intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) (Fig. 1). First, the invagination of the plasma membrane leads to the formation of early-sorting endosomes (ESEs). After maturing into late-sorting endosomes (LSEs), ESEs eventually generate MVBs containing ILVs by inward invagination of the endosomal limiting membrane. Last, ILVs are released into the extracellular milieu as exosomes upon the fusion of MVBs with the plasma membrane, supporting the endosomal mode of exosome biogenesis. Electron microscopy [40] and genetic studies [41, 42] have provided considerable evidence for the endosomal mode of exosome biogenesis. Since no specific markers of EV subtypes have been defined and ultracentrifugation is incapable of distinguishing exosomes from MVs, EVs which have only detected surface markers or sizes can not be considered as exosomes [43]. Therefore, we used the general term EVs instead of exosomes in this review unless authors have performed studies to determine that the EVs were of endosomal origin.

Microvesicles (MVs) or ectosomes are released by direct budding from the plasma membrane. Exosomes are formed by inward invagination of the endosomal limiting membrane, and released after late-sorting endosomes (LSEs) fusion with cell membrane. Exosome contains proteins, DNAs, mRNAs, ncRNAs (miRNAs, long noncoding RNAs and circRNAs) and metabolites. Previously reported EV ncRNAs in CC, OC and EC were listed in the boxes. miRNAs, long noncoding RNAs and circRNAs were respectively labeled in green, orange and blue.

The biogenesis of EVs determines their characteristics including the heterogeneity in size, content, biological marker, source and function. Combined asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation with real-time monitors revealed that exosomes may be classified into two distinct subsets: large exosomes (90–120 nm in diameter) and small exosomes (60–80 nm in diameter) [44, 45]. Meanwhile, EVs can be secreted by multiple cells types [46, 47], including macrophages [48], nervous cells, endothelial and epithelial cells [49], and mesenchymal stem cells [50, 51], which lead to the inclusion of different kinds of proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, and the expression of different detectable markers (CD81, CD82, CD37 and CD63) on EVs [52]. EVs with different labels can transfer contents to different recipient cells and tissues. Therefore, the heterogeneity of EVs contributed to the diversity and complexity of their function.

The functional role of EV ncRNAs in gynecological malignancy

Ratajczak et al. [53] first reported that mRNAs are selectively enriched in MVs derived from murine embryonic stem cells versus parental cells and that these mRNAs are further delivered to target cells to upregulate the expression of protein markers. Later, Valadi et al. reported that EVs derived from human and murine cell lines contain both mRNAs and small RNAs and that EV mRNAs transferred to other cells can also be translated to proteins in new cells, suggesting that EV mRNAs still function after transfer to the recipient cells [54]. Accumulating evidence has shown that EVs contain multiple types of ncRNAs, mainly miRNAs, lncRNAs and circRNAs. These EV ncRNAs, delivered to recipient cells by EVs, exert their functions and affect the cell phenotype, playing a significant role in various biological functions, particularly in cancer development.

EV ncRNAs derived from cancer or stromal cells serve as mediators among these cells, constitute critical component of tumor microenvironment (TME). EV ncRNAs from cancer cells can be transported not only to cancer cells, but also to other stromal cells, such as endothelial cells and immune cells. For example, EVs from CC and OC cells transported miR-221-3p [55,56,57], miR-141-3p [58], TUG1 [59] or MALAT1 [60] to human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLECs), microvascular endothelial cells (MVECs), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) or other endothelial cells, thus promoting endothelial cells proliferation, migration and tube formation, which facilitates to angiogenesis and cancer metastasis. And packaged in EVs, miR-21 [61] in EC and miR-1246 [62], miR-940 [63] and miR-222-3p [64] in OC can be transported to THP-1 or macrophages, which stimulated M2 phenotype polarization of macrophage, thus remodeling the tumor immune microenvironment and promoting cancer development. Meanwhile, miR-1246 was abundantly expressed in EVs derived from paclitaxel resistance-OC cells and miR-1246 inhibitor in combination with paclitaxel reduced tumor growth in mouse model, suggesting EV miR-1246 shuttling between cancer cells contributed to chemoresistance of OC. Besides, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs)-secreted EV ncRNAs can also be delivered to cancer cells and endothelial cells, promoting cancer cell proliferation, chemoresistance and angiogenesis, such as EV miR-98-5p [65], EV miR-21 [66] and EV miR-10a-5p [67]. In contrast, EV miR-146-5p from tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) and EV miR-424 from mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) can be transferred to HUVEC to inhibit angiogenesis [68, 69]. In addition, human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSCs) and MSC can also deliver EV ncRNAs to cancer cells to restrain the proliferation, migration, and invasion of cancer cells [69, 70]. However, normal cells can also secret EV ncRNAs and play a role in cancer inhibition. Human ovarian surface epithelial cells-secreted EV miR-124 can be transported to CAFs to reverse the transdifferentiation of normal fibroblasts (NFs) to CAFs and affect ECM remodeling [71]. All above findings demonstrated that EV ncRNAs mediated intercellular communication in the TME (Fig. 2), between cancer cells and stromal cells, which further remodeled TME and contributed to the cancer development and metastasis.

In summary, EV ncRNAs mostly regulate tumorigenesis and progression in following ways (Fig. 3): they (a) accelerate cancer progression by promoting cancer cell proliferation, (b) facilitate angiogenesis by altering the phenotype of endothelial cells, (c) promote metastasis and invasion by mediating EMT and transferring EV ncRNAs to distant tissues, (d) spread chemoresistance among heterogeneous populations of cancer cells, and (e) regulate the immune response. It has been reported that a large number of EV ncRNAs, listed in Table 1, function in the above ways in gynecological malignancies. Next, we summarized the functional roles of EV ncRNAs in CC, OC and EC.

EV ncRNAs in CC

CC continues to be a common gynecological malignancy. In 2018, there were 569,847 new cases and 311,365 deaths worldwide, making it the fourth most harmful malignancy threatening women’s health and lives [72]. Persistent infection with high-risk human papilloma virus (HPV) is the main risk factor, and HPV infection can be detected in nearly 99% of CC tissues; HPV 16 and 18 account for ~70% of HPV infections [73]. At present, the popularization of tertiary prevention makes CC controllable, but the prognosis of recurrent and metastatic CC is poor.

HPV infection affects the number and content of EVs and leads to the selective packaging of several miRNAs and lncRNAs into EVs[74]; the viral E6/E7 oncogene plays an important role in this process [75, 76]. EVs were found to be enriched in cervical-vaginal lavage specimens, and it was reported that 45 miRNAs were significantly upregulated and 55 miRNAs were significantly downregulated in EVs from cervical-vaginal lavage specimens from HPV 16-positive patients versus those from healthy volunteers [77]. In particular, EV miR-21 and miR-146a were markedly elevated in CC patients [78]. The lncRNAs HOTAIR, MALAT1 and MEG3 were also enriched in EVs derived from cervical-vaginal lavages and significantly upregulated in CC patients compared with cancer-free volunteers [79]. In plasma specimens, Zheng et al. reported that EV miR-30d-5p and let-7d-3p distinguished not only CC patients from normal patients but also cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) II+ group patients from CIN I− group patients [80]. In addition, the expression of lncRNA-EXOC7 was significantly upregulated in EVs from the serum and correlated with the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage [81]. These ncRNAs may serve as biomarkers for monitoring cancer occurrence and development. Compared to traditional solid biopsies, liquid biopsies have gained increasing attention as they can be performed easily and noninvasively [82].

In CC, EVs transfer ncRNAs to different recipient cells to play different roles in cancer development. For example, Zhou et al. reported that cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) cells secret EVs to accelerate cancer progression and metastasis by transferring miR-221-3p into different epithelial cells [55, 57]. EV miR-221-3p was delivered into human lymphatic endothelial cells (HLECs) to promote lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis by targeting vasohibin-1 (VASH1) [55], and delivered into human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) to promote angiogenesis by downregulating THBS2 [57]. Zhang et al. reported that EV miR-221-3p can also be transferred into microvascular endothelial cells (MVECs) to promote cell proliferation, invasion and migration by upregulating MAPK10 [56]. It was also reported that TUG1 is overexpressed in both CC cells and their secreted EVs [59]. EV TUG1 transferred to HUVEC promotes angiogenesis by regulating certain key angiogenesis-related genes. EV TUG1 also promotes HUVEC proliferation by regulating apoptosis-related proteins. Furthermore, EV ncRNAs participate in cancer drug resistance. Luo et al. reported that EVs secreted from cisplatin (DDP)-resistant HeLa cells transfer HNF1A‑AS1 to DDP‑sensitive HeLa cells. EV HNF1A‑AS1 sponges miR‑34b to upregulate TUFT1 expression, promoting the proliferation and drug resistance of cancer cells [83]. These studies not only showed the important role that EV ncRNAs play in CC development but also provided promising targets for the diagnosis and treatment of CC.

Finally, EVs can also be employed as shuttles to transfer functional moleculars to specified cells or tissues. Federico et al. delivered an anti-HPV16-E7 single-chain variable fragment (scFv) into cells to inhibit the proliferation of HPV16-E7-expressing cells by engineered EVs [84]. Unlike liposomes, which may induce undesired immune responses leading to low transport efficiency, endogenous EVs secreted by various cells are considered a natural ideal delivery system [85].

EV ncRNAs in OC

OC is one of the three major gynecological malignancies and has the highest mortality rate [86]. Owing to the lack of clinical symptoms in the early stage, more than 80% of OC patients are diagnosed at an advanced stage, always accompanied by metastasis to the peritoneal cavity or upper abdominal organs, leading the 5-year overall survival (OS) rate for stage III and IV disease is less than 30% [87]. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop biomarkers for the early diagnosis of OC.

A multitude of studies have reported that EV ncRNAs are differentially expressed in serum, plasma and ascites samples between normal and OC patients. It has been reported that the expression of serum EV miR-484 in OC patients is significantly decreased, which is not only closely related to cancer progression, but is also an independent predictor for OS and progression-free survival (PFS) of OC patients [88]. In contrast, the high expression of EV aHIF and MALAT1 in the serum of OC patients may predict poor OS [60, 89]. However, serum EV miR-375, miR-1307 and miR-34a may be used as diagnostic biomarkers due to their abnormal expression in patients with advanced stage disease or with lymph node metastasis [90, 91]. In addition, EV ncRNAs in plasma, ascites, or cancer cells may also be used as biomarkers. miR-21, miR-100, miR-200b, and miR-320 were all upregulated in the plasma of OC patients, and miR-200b was closely related to patient OS [92]. Differential expression of EV miRNAs was also detected in ascites from OC patients, among which miR-149-3p and miR-222-5p were significantly correlated with 5-year survival and OS [93]. The aforementioned ncRNAs are enriched in EVs and can be easily collected and detected, so they may serve as potential biomarkers to improve the efficiency of diagnosis and disease for OC.

EV ncRNAs also regulate OC development by acting as oncogenes or tumor suppressors. On the one hand, it has been reported that EV miR-205 and miR-141-3p derived from OC cells promote cell proliferation, migration, invasion and angiogenesis [58, 94, 95]. In particular, EV miR-99a-5p derived from epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) cells can be transferred to neighboring human peritoneal mesothelial cells and upregulate the expression of fibronectin and vitronectin, promoting OC cell invasion [96]. Additionally, multiple types of cells secrete EV ncRNAs to promote sensitive cancer cell chemoresistance. Yeung et al. reported that EV miR-21 derived from cancer-associated adipocytes (CAAs) and fibroblasts (CAFs) confers cancer cell chemoresistance by binding to APAF1 [66]. Luo et al. also reported that circulating EV circFoxp1 confers EOC cell chemoresistance [97]. In addition, MDA-MB-231 cells transfer EV microRNA-454 to promote the stemness of cancer stem cells in OC [98]. Therefore, these EV ncRNAs promote OC progression by regulating the proliferation, migration, invasion, and chemoresistance of cancer cells.

On the other hand, EV ncRNAs, such as EV miR-34b, miR-124 and miR-6126, function as tumor suppressors in OC progression [71, 99, 100]. For example, miR‐124 transfer from human ovarian surface epithelial cells to CAFs leads to the attenuation of cell motility and invasion. Specifically, miR‐124 binds to the 3’ UTR of SPHK1 mRNA to inhibit SPHK1 expression, which promotes the transition of normal fibroblasts to CAFs, thereby contributing to extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling [71]. Another example is EV miRNA-7 derived from tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK)-stimulated macrophages, which inhibits cancer metastasis after transfer to EOC cells [101]. The overexpression of these miRNAs inhibits cancer progression, suggesting they may provide new therapeutic approach to cancer treatment.

EV ncRNAs in EC

Both the incidence and mortality rates of EC, the most common gynecological malignancy in developed countries, are increasing [3, 102]. It was predicted that by 2030, the EC incidence rate is expected to reach over 42.13 cases per 100,000 women [103]. Based on the clinical features, grade, hormone receptor expression, histology and other related factors, EC is divided into two classes: type I and type II. Unlike type I, which has a good prognosis, type II EC is usually diagnosed at an advanced stage, accompanied by distant metastasis, which indicates a poor prognosis [104].

Although studies on EV ncRNAs in EC are limited, the existing data provide a starting point for fully characterizing these components in EC. Similar to CC and OC, certain ncRNAs are enriched in EVs from EC patients. It has been reported that circRNAs are differentially expressed in serum EVs between EC patients and normal controls [105]. The urine-derived EVs in EC patients revealed that miRNAs are also be selectively packaged into EVs and that miR-200c-3p was significantly enriched in these EVs [106]. In addition, 114 miRNAs were differentially expressed in EVs derived from peritoneal lavage samples from EC patients compared with control patients, and among these miRNAs 18 were upregulated and 96 were downregulated. Importantly, 8 significantly downregulated miRNAs were found to have predictive value [107]. These EV ncRNAs provide a novel avenue for improving the clinical diagnosis and management of cancer.

It was reported that cancer-associated fibroblast (CAFs)-secreted EV miRNAs can suppress cancer progression. Zhang et al. reported that EV miR-320a secreted by CAFs inhibits cancer cell proliferation via HIF1α/VEGFA axis [108]. Similarly, EV miR‐148b derived from CAFs suppresses EC metastasis, by directly binding to DNMT1 [109]. However, downregulated miR-320a and miR‐148b in CAFs and CAFs‐derived exosomes induced EMT to promote endometrial EC progression. In contrast, EV ncRNAs may also accelerate EC progression. The overexpression of miR-381-3p in tumor tissues was found to reduce E2F3 expression to inhibit the proliferation, migration, and invasion of EC cells. However, EV DLEU1 accelerate EC progression by negatively regulating the miR-381-3p/E2F3 axis [110]. Furthermore, EV miR-21, which was secreted from EC KEL cells at a higher level under hypoxic conditions than under normoxic conditions, was transferred into THP-1 cells to promote M2-like macrophage polarization, suggesting that EV ncRNAs participate in the cancer immune microenvironment [61]. These results suggest that EV ncRNAs also play a significant role in EC progression. As our understanding of EV ncRNAs increases, new biomarkers or therapeutic approaches to improve EC management will be revealed.

Conclusion and future perspectives

Similar to their application in other cancers, the clinical applications of EV ncRNAs in gynecological malignancies are mainly focused on two aspects. Increasing evidence has shown that EV ncRNAs have the potential to serve as biomarkers for cancer diagnosis as well as for the prediction and monitoring of therapeutic effects (Table 2). The membrane structures of EVs provide a shell to protect ncRNAs from degradation by endogenous RNase. EVs can be secreted into serum, urine, saliva, ascites, pleural fluid and so on. These biological fluids are easy to sample, making EV ncRNAs ideal biomarkers. Importantly, EVs can be secreted by almost all kinds of cells, indicating that they can reflect the pathological and physiological conditions of donor cells. Therefore, EV ncRNA detection through liquid biopsy provides a novel method for cancer diagnosis and monitoring.

Due to the natural characteristics of EVs and the development of engineering technology, EVs have been suggested to have potential applications in cancer treatment. EV ncRNAs have a vital role in cancer progression and chemoresistance, which may be restrained by inhibiting the release and uptake of cancer-related EVs. Because certain membrane proteins are overexpressed in cancer-related EVs, EVs can also be employed as shuttles to transfer functional moleculars to specified cells or tissues. It has been reported that the nonapeptide LXY30 can reduce EV uptake into OC cells by binding to the overexpressed membrane protein α3β1 integrin [111]. In addition, unlike liposomes, which may induce undesired immune responses leading to low transport efficiency, endogenous EVs secreted by various cells are considered a natural ideal drug delivery system [85]. Aqil et al. employed milk EVs to deliver plant bioactive berry Anthos, which enhanced the drug’s antiproliferative activity against OC cells by enhancing its oral bioavailability [112]. Zhang et al. reported that umbilical cord-derived macrophage EVs loaded with cisplatin increased their cytotoxicity in both drug-resistant and drug-sensitive OC cells, significantly improving the efficacy of cisplatin [113]. This emerging therapeutic approach can improve drug loading, enhance endocytosis, lower toxicity and protect contents from degradation, making EVs an ideal drug delivery system. Moreover, investigating the mechanisms by which EV ncRNAs confer chemoresistance could improve our knowledge about chemoresistance, providing more treatment opinions. Furthermore, EVs may be developed as vaccines to stimulate anticancer immunity. EV-based vaccines may stimulate both adaptive and innate immunity. The group of Maurizio Federico engineered endogenous EVs loaded with HPV E7 protein, which induces a protective CD8+ T cell immune response [114]. They also produced immunogenic EVs in vivo by injection of Nefmut/E7 DNA to elicit an E7-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) immune response [115]. Above all, these results represent emerging novel applications of EVs in cancer therapy.

Taken together, these findings indicate that EV-delivered ncRNAs extensively participate in the development of gynecological malignancies. Many studies have attempted to elucidate the mechanism by which EV ncRNAs are produced and their biological roles in the occurrence and progression of gynecological malignancies. Numerous studies have also striven to employ these EV ncRNAs to diagnose or monitor cancer progression. Some studies have even applied EVs to treat gynecological malignancies or elicit cancer-associated immune responses. Although these applications are under development and exploration, they bring new ideas and hope for improving the diagnosis and treatment of gynecological malignancies.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Lheureux S, Gourley C, Vergote I, Oza AM. Epithelial ovarian cancer. Lancet. 2019;393:1240–53.

Cohen PA, Jhingran A, Oaknin A, Denny L. Cervical cancer. Lancet. 2019;393:169–82.

Lu KH, Broaddus RR. Endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2053–64.

Zhang X, Xie K, Zhou H, Wu Y, Li C, Liu Y, et al. Role of non-coding RNAs and RNA modifiers in cancer therapy resistance. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:47.

Tornesello ML, Faraonio R, Buonaguro L, Annunziata C, Starita N, Cerasuolo A, et al. The role of microRNAs, long non-coding RNAs, and circular RNAs in cervical cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:150.

Dong P, Xu D, Xiong Y, Yue J, Ihira K, Konno Y. et al. The expression, functions and mechanisms of circular RNAs in gynecological cancers. Cancers. Cancers. 2020;12:1472.

Xie Y, Dang W, Zhang S, Yue W, Yang L, Zhai X, et al. The role of exosomal noncoding RNAs in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:37.

Zhao W, Liu Y, Zhang C, Duan C. Multiple roles of exosomal long noncoding RNAs in cancers. BioMed Res Int. 2019;2019:1460572.

Wang W, Han Y, Jo HA, Lee J, Song YS. Non-coding RNAs shuttled via exosomes reshape the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13:67.

Ma P, Pan Y, Li W, Sun C, Liu J, Xu T, et al. Extracellular vesicles-mediated noncoding RNAs transfer in cancer. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:57.

Pathan M, Fonseka P, Chitti SV, Kang T, Sanwlani R, Van Deun J, et al. Vesiclepedia 2019: a compendium of RNA, proteins, lipids and metabolites in extracellular vesicles. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D516–D519.

Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, Al Saffar H, Anand S, Zhao K, et al. ExoCarta: a web-based compendium of exosomal cargo. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:688–92.

Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21:9–17.

Li X, Wang X. The emerging roles and therapeutic potential of exosomes in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer. 2017;16:92.

Bartel DP. Metazoan microRNAs. Cell. 2018;173:20–51.

Yang Z, Sun Q, Guo J, Wang S, Song G, Liu W, et al. GRSF1-mediated MIR-G-1 promotes malignant behavior and nuclear autophagy by directly upregulating TMED5 and LMNB1 in cervical cancer cells. Autophagy. 2019;15:668–85.

Muys BR, Sousa JF, Plaça JR, de Araújo LF, Sarshad AA, Anastasakis DG, et al. miR-450a acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer by regulating energy metabolism. Cancer Res. 2019;79:3294–305.

Zhang J, Gao Y. Long non-coding RNA MEG3 inhibits cervical cancer cell growth by promoting degradation of P-STAT3 protein via ubiquitination. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:175.

Li Q, Feng Y, Chao X, Shi S, Liang M, Qiao Y. et al. HOTAIR contributes to cell proliferation and metastasis of cervical cancer via targetting miR-23b/MAPK1 axis. Biosci Rep. 2018;38:BSR2017156.

Ding X, Jia X, Wang C, Xu J, Gao SJ, Lu C. A DHX9-lncRNA-MDM2 interaction regulates cell invasion and angiogenesis of cervical cancer. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1750–65.

Song T, Xu A, Zhang Z, Gao F, Zhao L, Chen X, et al. CircRNA hsa_circRNA_101996 increases cervical cancer proliferation and invasion through activating TPX2 expression by restraining miR-8075. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:14296–305.

Ding L, Zhang H. Circ-ATP8A2 promotes cell proliferation and invasion as a ceRNA to target EGFR by sponging miR-433 in cervical cancer. Gene. 2019;705:103–8.

Rong X, Gao W, Yang X, Guo J. Downregulation of hsa_circ_0007534 restricts the proliferation and invasion of cervical cancer through regulating miR-498/BMI-1 signaling. Life Sci. 2019;235:116785.

Shao S, Wang C, Wang S, Zhang H, Zhang Y. Hsa_circ_0075341 is up-regulated and exerts oncogenic properties by sponging miR-149-5p in cervical cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;121:109582.

Xie J, Wang S, Li G, Zhao X, Jiang F, Liu J, et al. circEPSTI1 regulates ovarian cancer progression via decoying miR-942. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:3597–602.

Chen Q, Zhang J, He Y, Wang Y. hsa_circ_0061140 knockdown reverses FOXM1-mediated cell growth and metastasis in ovarian cancer through miR-370 sponge activity. Mol Ther Nucleic acids. 2018;13:55–63.

Zong Z-H, Du Y-P, Guan X, Chen S, Zhao Y. CircWHSC1 promotes ovarian cancer progression by regulating MUC1 and hTERT through sponging miR-145 and miR-1182. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:437.

Zhang S, Cheng J, Quan C, Wen H, Feng Z, Hu Q, et al. circCELSR1 (hsa_circ_0063809) contributes to paclitaxel resistance of ovarian cancer cells by regulating FOXR2 expression via miR-1252. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2020;19:718–30.

Wang J, Zhu S, Meng N, He Y, Lu R, Yan GR. ncRNA-encoded peptides or proteins and cancer. Mol Ther. 2019;27:1718–25.

Huang JZ, Chen M, Chen D, Gao XC, Zhu S, Huang H, et al. A peptide encoded by a putative lncRNA HOXB-AS3 suppresses colon cancer growth. Mol Cell. 2017;68:171–184.e6.

Zhang M, Zhao K, Xu X, Yang Y, Yan S, Wei P, et al. A peptide encoded by circular form of LINC-PINT suppresses oncogenic transcriptional elongation in glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2018;9:4475.

Zhang M, Huang N, Yang X, Luo J, Yan S, Xiao F, et al. A novel protein encoded by the circular form of the SHPRH gene suppresses glioma tumorigenesis. Oncogene 2018;37:1805–14.

Yang Y, Gao X, Zhang M, Yan S, Sun C, Xiao F, et al. Novel role of FBXW7 circular RNA in repressing glioma tumorigenesis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:djx166.

Xia X, Li X, Li F, Wu X, Zhang M, Zhou H, et al. A novel tumor suppressor protein encoded by circular AKT3 RNA inhibits glioblastoma tumorigenicity by competing with active phosphoinositide-dependent Kinase-1. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:131.

Zheng X, Chen L, Zhou Y, Wang Q, Zheng Z, Xu B, et al. A novel protein encoded by a circular RNA circPPP1R12A promotes tumor pathogenesis and metastasis of colon cancer via Hippo-YAP signaling. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:47.

Pang Y, Liu Z, Han H, Wang B, Li W, Mao C, et al. Peptide SMIM30 promotes HCC development by inducing SRC/YES1 membrane anchoring and MAPK pathway activation. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1155–69.

Meng N, Chen M, Chen D, Chen XH, Wang JZ, Zhu S, et al. Small protein hidden in lncRNA LOC90024 promotes “cancerous” RNA splicing and tumorigenesis. Adv Sci. 2020;7:1903233.

Kang M, Tang B, Li J, Zhou Z, Liu K, Wang R, et al. Identification of miPEP133 as a novel tumor-suppressor microprotein encoded by miR-34a pri-miRNA. Mol Cancer. 2020;19:143.

ELA S, Mäger I, Breakefield XO, Wood MJ. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Disco. 2013;12:347–57.

Chuo ST-Y, Chien JC-Y, Lai CP-K. Imaging extracellular vesicles: current and emerging methods. J Biomed Sci. 2018;25:91.

Ostrowski M, Carmo NB, Krumeich S, Fanget I, Raposo G, Savina A, et al. Rab27a and Rab27b control different steps of the exosome secretion pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:19–30. sup pp 1–13.

Hyenne V, Apaydin A, Rodriguez D, Spiegelhalter C, Hoff-Yoessle S, Diem M, et al. RAL-1 controls multivesicular body biogenesis and exosome secretion. J Cell Biol. 2015;211:27–37.

Théry C, Witwer KW, Aikawa E, Alcaraz MJ, Anderson JD, Andriantsitohaina R, et al. Minimal information for studies of extracellular vesicles 2018 (MISEV2018): a position statement of the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles and update of the MISEV2014 guidelines. J Extracell Vesicles. 2018;7:1535750.

Zhang H, Freitas D, Kim HS, Fabijanic K, Li Z, Chen H, et al. Identification of distinct nanoparticles and subsets of extracellular vesicles by asymmetric flow field-flow fractionation. Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20:332–43.

Zhang H, Lyden D. Asymmetric-flow field-flow fractionation technology for exomere and small extracellular vesicle separation and characterization. Nat Protoc. 2019;14:1027–53.

Sinha A, Ignatchenko V, Ignatchenko A, Mejia-Guerrero S, Kislinger T. In-depth proteomic analyses of ovarian cancer cell line exosomes reveals differential enrichment of functional categories compared to the NCI 60 proteome. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;445:694–701.

Shi S, Tan Q, Feng F, Huang H, Liang J, Cao D, et al. Identification of core genes in the progression of endometrial cancer and cancer cell-derived exosomes by an integrative analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9862.

Hou Y, Liu Y, Liang S, Ding R, Mo S, Yan D, et al. The novel target: exosoms derived from M2 macrophage. Int Rev Immunol. 2020;40:1–14.

He S, Chen D, Hu M, Zhang L, Liu C, Traini D, et al. Bronchial epithelial cell extracellular vesicles ameliorate epithelial-mesenchymal transition in COPD pathogenesis by alleviating M2 macrophage polarization. Nanomedicine. 2019;18:259–71.

Huang Y. Exosomal lncRNAs from mesenchymal stem cells as the novel modulators to cardiovascular disease. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:315.

Alzahrani FA, El-Magd MA, Abdelfattah-Hassan A, Saleh AA, Saadeldin IM, El-Shetry ES, et al. Potential effect of exosomes derived from cancer stem cells and MSCs on progression of DEN-induced HCC in rats. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:8058979.

Escola JM, Kleijmeer MJ, Stoorvogel W, Griffith JM, Yoshie O, Geuze HJ. Selective enrichment of tetraspan proteins on the internal vesicles of multivesicular endosomes and on exosomes secreted by human B-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:20121–7.

Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, Zhang J, Reca R, Dvorak P, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20:847–56.

Valadi H, Ekström K, Bossios A, Sjöstrand M, Lee JJ, Lötvall JO. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–9.

Zhou C-F, Ma J, Huang L, Yi H-Y, Zhang Y-M, Wu X-G, et al. Cervical squamous cell carcinoma-secreted exosomal miR-221-3p promotes lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis by targeting VASH1. Oncogene. 2019;38:1256–68.

Zhang L, Li H, Yuan M, Li M, Zhang S. Cervical cancer cells-secreted exosomal microRNA-221-3p promotes invasion, migration and angiogenesis of microvascular endothelial cells in cervical cancer by down-regulating MAPK10 expression. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:10307–19.

Wu XG, Zhou CF, Zhang YM, Yan RM, Wei WF, Chen XJ, et al. Cancer-derived exosomal miR-221-3p promotes angiogenesis by targeting THBS2 in cervical squamous cell carcinoma. Angiogenesis. 2019;22:397–410.

Masoumi-Dehghi S, Babashah S, Sadeghizadeh M. microRNA-141-3p-containing small extracellular vesicles derived from epithelial ovarian cancer cells promote endothelial cell angiogenesis through activating the JAK/STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways. J Cell Commun Signal. 2020;14:233–44.

Lei L, Mou Q. Exosomal taurine up-regulated 1 promotes angiogenesis and endothelial cell proliferation in cervical cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2020;21:717–25.

Qiu JJ, Lin XJ, Tang XY, Zheng TT, Lin YY, Hua KQ. Exosomal metastasis‑associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 promotes angiogenesis and predicts poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14:1960–73.

Xiao L, He Y, Peng F, Yang J, Yuan C. Endometrial cancer cells promote M2-like macrophage polarization by delivering exosomal miRNA-21 under hypoxia condition. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:9731049.

Kanlikilicer P, Bayraktar R, Denizli M, Rashed MH, Ivan C, Aslan B, et al. Exosomal miRNA confers chemo resistance via targeting Cav1/p-gp/M2-type macrophage axis in ovarian cancer. EBioMedicine. 2018;38:100–12.

Chen X, Ying X, Wang X, Wu X, Zhu Q, Wang X. Exosomes derived from hypoxic epithelial ovarian cancer deliver microRNA-940 to induce macrophage M2 polarization. Oncol Rep. 2017;38:522–8.

Ying X, Wu Q, Wu X, Zhu Q, Wang X, Jiang L, et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer-secreted exosomal miR-222-3p induces polarization of tumor-associated macrophages. Oncotarget 2016;7:43076–87.

Guo H, Ha C, Dong H, Yang Z, Ma Y, Ding Y. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived exosomal microRNA-98-5p promotes cisplatin resistance in ovarian cancer by targeting CDKN1A. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:347.

Au Yeung CL, Co NN, Tsuruga T, Yeung TL, Kwan SY, Leung CS, et al. Exosomal transfer of stroma-derived miR21 confers paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells through targeting APAF1. Nat Commun. 2016;7:11150.

Zhang X, Wang Y, Wang X, Zou B, Mei J, Peng X, et al. Extracellular vesicles-encapsulated microRNA-10a-5p shed from cancer-associated fibroblast facilitates cervical squamous cell carcinoma cell angiogenesis and tumorigenicity via Hedgehog signaling pathway. Cancer Gene Ther. 2020;28:529–42.

Wu Q, Wu X, Ying X, Zhu Q, Wang X, Jiang L, et al. Suppression of endothelial cell migration by tumor associated macrophage-derived exosomes is reversed by epithelial ovarian cancer exosomal lncRNA. Cancer Cell Int. 2017;17:62.

Li P, Xin H, Lu L. Extracellular vesicle-encapsulated microRNA-424 exerts inhibitory function in ovarian cancer by targeting MYB. J Transl Med. 2021;19:4.

Meng Q, Zhang B, Zhang Y, Wang S, Zhu X. Human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles impede the progression of cervical cancer via the miR-144-3p/CEP55 pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25:1867–83.

Zhang Y, Cai H, Chen S, Sun D, Zhang D, He Y. Exosomal transfer of miR-124 inhibits normal fibroblasts to cancer-associated fibroblasts transition by targeting sphingosine kinase 1 in ovarian cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:13187–201.

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.

zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses and cancer: from basic studies to clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:342–50.

Harden ME, Munger K. Human papillomavirus 16 E6 and E7 oncoprotein expression alters microRNA expression in extracellular vesicles. Virology.2017;508:63–9.

Honegger A, Leitz J, Bulkescher J, Hoppe-Seyler K, Hoppe-Seyler F. Silencing of human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 oncogene expression affects both the contents and the amounts of extracellular microvesicles released from HPV-positive cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:1631–42.

Honegger A, Schilling D, Bastian S, Sponagel J, Kuryshev V, Sültmann H, et al. Dependence of intracellular and exosomal microRNAs on viral E6/E7 oncogene expression in HPV-positive tumor cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004712.

Wu Y, Wang X, Meng L, Li W, Li C, Li P, et al. Changes of miRNA expression profiles from cervical-vaginal fluid-derived exosomes in response to HPV16 infection. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:7046894.

Liu J, Sun H, Wang X, Yu Q, Li S, Yu X, et al. Increased exosomal microRNA-21 and microRNA-146a levels in the cervicovaginal lavage specimens of patients with cervical cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:758–73.

Zhang J, Liu S-C, Luo X-H, Tao G-X, Guan M, Yuan H, et al. Exosomal long noncoding RNAs are differentially expressed in the cervicovaginal lavage samples of cervical cancer patients. J Clin Lab Anal. 2016;30:1116–21.

Zheng M, Hou L, Ma Y, Zhou L, Wang F, Cheng B, et al. Exosomal let-7d-3p and miR-30d-5p as diagnostic biomarkers for non-invasive screening of cervical cancer and its precursors. Mol Cancer. 2019;18:76.

Guo Y, Wang X, Wang K, He Y. Appraising the value of serum and serum-derived exosomal LncRNA-EXOC7 as a promising biomarker in cervical cancer. Clin Lab. 2020;66:7.

Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14:531–48.

Luo X, Wei J, Yang FL, Pang XX, Shi F, Wei YX, et al. Exosomal lncRNA HNF1A-AS1 affects cisplatin resistance in cervical cancer cells through regulating microRNA-34b/TUFT1 axis. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:323.

Ferrantelli F, Arenaccio C, Manfredi F, Olivetta E, Chiozzini C, Leone P, et al. The intracellular delivery of anti-HPV16 E7 scFvs through engineered extracellular vesicles inhibits the proliferation of HPV-infected cells. Int J Nanomed. 2019;14:8755–68.

Liao W, Du Y, Zhang C, Pan F, Yao Y, Zhang T, et al. Exosomes: the next generation of endogenous nanomaterials for advanced drug delivery and therapy. Acta Biomater. 2019;86:1–14.

Kuroki L, Guntupalli SR. Treatment of epithelial ovarian cancer. BMJ. 2020;371:m3773.

Calanca N, Abildgaard C, Rainho CA, Rogatto SR. The interplay between long noncoding RNAs and proteins of the epigenetic machinery in ovarian cancer. Cancers. 2020;12:2701.

Zhang W, Su X, Li S, Liu Z, Wang Q, Zeng H. Low serum exosomal miR-484 expression predicts unfavorable prognosis in ovarian cancer. Cancer Biomark. 2020;27:485–91.

Tang X, Liu S, Liu Y, Lin X, Zheng T, Liu X, et al. Circulating serum exosomal aHIF is a novel prognostic predictor for epithelial ovarian cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:7699–711.

Su YY, Sun L, Guo ZR, Li JC, Bai TT, Cai XX, et al. Upregulated expression of serum exosomal miR-375 and miR-1307 enhance the diagnostic power of CA125 for ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2019;12:6.

Maeda K, Sasaki H, Ueda S, Miyamoto S, Terada S, Konishi H, et al. Serum exosomal microRNA-34a as a potential biomarker in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2020;13:47.

Pan C, Stevic I, Müller V, Ni Q, Oliveira-Ferrer L, Pantel K, et al. Exosomal microRNAs as tumor markers in epithelial ovarian cancer. Mol Oncol. 2018;12:1935–48.

Li Y, Liu C, Liao Y, Wang W, Hu B, Lu X, et al. Characterizing the landscape of peritoneal exosomal microRNAs in patients with ovarian cancer by high-throughput sequencing. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:539–47.

Wang L, Zhao F, Xiao Z, Yao L. Exosomal microRNA-205 is involved in proliferation, migration, invasion, and apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells via regulating VEGFA. Cancer Cell Int. 2019;19:281.

He L, Zhu W, Chen Q, Yuan Y, Wang Y, Wang J, et al. Ovarian cancer cell-secreted exosomal miR-205 promotes metastasis by inducing angiogenesis. Theranostics. 2019;9:8206–20.

Yoshimura A, Sawada K, Nakamura K, Kinose Y, Nakatsuka E, Kobayashi M, et al. Exosomal miR-99a-5p is elevated in sera of ovarian cancer patients and promotes cancer cell invasion by increasing fibronectin and vitronectin expression in neighboring peritoneal mesothelial cells. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:1065.

Luo Y, Gui R. Circulating exosomal circFoxp1 confers cisplatin resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer cells. J Gynecol Oncol. 2020;31:e75.

Wang L, He M, Fu L, Jin Y. Exosomal release of microRNA-454 by breast cancer cells sustains biological properties of cancer stem cells via the PRRT2/Wnt axis in ovarian cancer. Life Sci. 2020;257:118024.

Lu S, Liu W, Shi H, Zhou H. Exosomal miR-34b inhibits proliferation and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition by targeting Notch2 in ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett. 2020;20:2721–8.

Kanlikilicer P, Rashed MH, Bayraktar R, Mitra R, Ivan C, Aslan B, et al. Ubiquitous release of exosomal tumor suppressor miR-6126 from ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2016;76:7194–207.

Hu Y, Li D, Wu A, Qiu X, Di W, Huang L, et al. TWEAK-stimulated macrophages inhibit metastasis of epithelial ovarian cancer via exosomal shuttling of microRNA. Cancer Lett. 2017;393:60–7.

Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, Abu-Rustum N, Darai E. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2016;387:1094–108.

Sheikh MA, Althouse AD, Freese KE, Soisson S, Edwards RP, Welburn S, et al. USA endometrial cancer projections to 2030: should we be concerned? Future Oncol. 2014;10:2561–8.

Ryan AJ, Susil B, Jobling TW, Oehler MK. Endometrial cancer. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:53–61.

Xu H, Gong Z, Shen Y, Fang Y, Zhong S. Circular RNA expression in extracellular vesicles isolated from serum of patients with endometrial cancer. Epigenomics. 2018;10:187–97.

Srivastava A, Moxley K, Ruskin R, Dhanasekaran DN, Zhao YD, Ramesh R. A non-invasive liquid biopsy screening of urine-derived exosomes for miRNAs as biomarkers in endometrial cancer patients. Aaps J. 2018;20:82.

Roman-Canal B, Moiola CP, Gatius S, Bonnin S, Ruiz-Miró M, González E, et al. EV-Associated miRNAs from peritoneal lavage are a source of biomarkers in endometrial cancer. Cancers. 2019;11:839.

Zhang N, Wang Y, Liu H, Shen W. Extracellular vesicle encapsulated microRNA-320a inhibits endometrial cancer by suppression of the HIF1α/VEGFA axis. Exp Cell Res. 2020;394:112113.

Li BL, Lu W, Qu JJ, Ye L, Du GQ, Wan XP. Loss of exosomal miR-148b from cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes endometrial cancer cell invasion and cancer metastasis. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:2943–53.

Jia J, Guo S, Zhang D, Tian X, Xie X. Exosomal-lncRNA DLEU1 accelerates the proliferation, migration, and invasion of endometrial carcinoma cells by regulating microRNA-E2F3. OncoTargets Ther. 2020;13:8651–63.

Carney RP, Hazari S, Rojalin T, Knudson A, Gao T, Tang Y, et al. Targeting tumor-associated exosomes with integrin-binding peptides. Adv Biosyst. 2017;1:1600038.

Aqil F, Jeyabalan J, Agrawal AK, Kyakulaga A-H, Munagala R, Parker L, et al. Exosomal delivery of berry anthocyanidins for the management of ovarian cancer. Food Funct. 2017;8:4100–7.

Zhang X, Liu L, Tang M, Li H, Guo X, Yang X. The effects of umbilical cord-derived macrophage exosomes loaded with cisplatin on the growth and drug resistance of ovarian cancer cells. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2020;46:1150–62.

Di Bonito P, Ridolfi B, Columba-Cabezas S, Giovannelli A, Chiozzini C, Manfredi F, et al. HPV-E7 delivered by engineered exosomes elicits a protective CD8+ T cell-mediated immune response. Viruses. 2015;7:1079–99.

Di Bonito P, Chiozzini C, Arenaccio C, Anticoli S, Manfredi F, Olivetta E, et al. Antitumor HPV E7-specific CTL activity elicited by in vivo engineered exosomes produced through DNA inoculation. Int J Nanomed. 2017;12:4579–91.

Zhou C, Wei W, Ma J, Yang Y, Liang L, Zhang Y, et al. Cancer-secreted exosomal miR-1468-5p promotes tumor immune escape via the immunosuppressive reprogramming of lymphatic vessels. Mol Ther. 2020;29:1512–28.

Zhu X, Shen H, Yin X, Yang M, Wei H, Chen Q, et al. Macrophages derived exosomes deliver miR-223 to epithelial ovarian cancer cells to elicit a chemoresistant phenotype. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:81.

Reza A, Choi YJ, Yasuda H, Kim JH. Human adipose mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomal-miRNAs are critical factors for inducing anti-proliferation signalling to A2780 and SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38498.

Liu R, Zhang Y, Sun P, Wang C. DDP-resistant ovarian cancer cells-derived exosomal microRNA-30a-5p reduces the resistance of ovarian cancer cells to DDP. Open Biol. 2020;10:190173.

Che X, Jian F, Chen C, Liu C, Liu G, Feng W. PCOS serum-derived exosomal miR-27a-5p stimulates endometrial cancer cells migration and invasion. J Mol Endocrinol. 2020;64:1–12.

Jing L, Hua X, Yuanna D, Rukun Z, Junjun M. Exosomal miR-499a-5p inhibits endometrial cancer growth and metastasis via targeting VAV3. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:13541–52.

Lv A, Tu Z, Huang Y, Lu W, Xie B. Circulating exosomal miR-125a-5p as a novel biomarker for cervical cancer. Oncol Lett. 2021;21:54.

Kim S, Choi MC, Jeong JY, Hwang S, Jung SG, Joo WD, et al. Serum exosomal miRNA-145 and miRNA-200c as promising biomarkers for preoperative diagnosis of ovarian carcinomas. J Cancer. 2019;10:1958–67.

Meng X, Müller V, Milde-Langosch K, Trillsch F, Pantel K, Schwarzenbach H. Diagnostic and prognostic relevance of circulating exosomal miR-373, miR-200a, miR-200b and miR-200c in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:16923–35.

Kobayashi M, Sawada K, Nakamura K, Yoshimura A, Miyamoto M, Shimizu A, et al. Exosomal miR-1290 is a potential biomarker of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma and can discriminate patients from those with malignancies of other histological types. J Ovarian Res. 2018;11:81.

Zhang H, Xu S, Liu X. MicroRNA profiling of plasma exosomes from patients with ovarian cancer using high-throughput sequencing. Oncol Lett. 2019;17:5601–7.

Kobayashi M, Salomon C, Tapia J, Illanes SE, Mitchell MD, Rice GE. Ovarian cancer cell invasiveness is associated with discordant exosomal sequestration of Let-7 miRNA and miR-200. J Transl Med. 2014;12:4.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was granted by “Zhong Yuan Thousand Talents Program-the Zhong Yuan Eminent Doctor in Henan Province” (ZYQR201810107), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2004117), “Zhong Yuan Elite Project-the Zhong Yuan Leading Talents for Science and Technology Innovation” (YXKC2020012) and Henan Postdoctoral Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS drew the table, organized and wrote the manuscript. LS, JB, HF and HQ contributed to the collection of related literatures. RG read and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Si, L., Bai, J., Fu, H. et al. The functions and potential roles of extracellular vesicle noncoding RNAs in gynecological malignancies. Cell Death Discov. 7, 258 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-021-00645-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41420-021-00645-3