Abstract

Background

The extent and severity of post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms among frontline clinicians are not clear. This study compared mental health symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms) and global quality of life (QOL) after the first COVID-19 outbreak between the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians.

Methods

This cross-sectional, comparative, convenient-sampling study was conducted between October 13 and 22, 2020, which was five months after the first COVID-19 outbreak in China was brought under control. The severity of depression, anxiety, insomnia symptoms, and global QOL of the clinicians were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale—7 items (GAD-7), Insomnia Severity Index (ISI), and the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire—brief version (WHOQOL-BREF), respectively. The propensity score matching (PSM) method was used to identify comparable COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians. A generalized linear model (GLM) was used to assess the differences in PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI, and QOL scores between the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians.

Results

In total, 260 COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians and 260 matched non- COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians were included. Non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians experienced more frequent workplace violence (WPV) than the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians (χ2 = 7.6, p = 0.006). COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians reported higher QOL compared to their non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts (b = 0.3, p = 0.042), after adjusting for WPV experience. COVID-19 treating and non- COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians reported similar PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI total scores (all p values > 0.05).

Conclusion

This study did not reveal more severe post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms in COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians compared to non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians. It is possible that the implementation of timely and appropriate mental health, social and financial supports could have prevented the worsening of mental health symptoms among the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians after the first COVID-19 outbreak in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was first reported in the Hubei province of China at the end of 2019 [1] and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 [2]. Since then, it has emerged in over 200 countries and territories [3]. Due to the relatively high death rate [4, 5], fast transmission, and lack of effective treatment of COVID-19, a vast number of clinicians volunteered to join the frontline efforts to combat COVID-19 in Hubei province in early 2020 [6,7,8].

During the first COVID-19 outbreak, due to a large number of infected patients and a shortage of personal protective gear, COVID-19 treating frontline healthcare staff experienced a very high heavy workload and risk of infection with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [9], both of which could increase the risk of mental health problems. A previous study found that the prevalence of depression, anxiety, insomnia, and distress symptoms were 50, 45, 34, and 72%, respectively, among the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [10]. Several comparative studies also found that COVID-19 treating frontline healthcare workers were at higher risk of mental health consequences such as depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and trauma compared to non-COVID-19 treating frontline healthcare workers [10,11,12,13,14]. However, most studies were conducted at the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak (before May 2020), and very few studies compared the post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms between COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians.

Previous studies on the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak found that COVID-19 treating frontline healthcare professionals experienced a higher risk of psychological problems such as distress, post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), and burnout compared to their non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts even one year after the SARS outbreak [15]. The COVID-19 pandemic has persisted longer than expected and is likely to be endemic for some time [16, 17]; therefore, understanding the post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms among COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians is important [18] to reduce its long-term impact.

This study compared the post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms) and global QOL between the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians after the first COVID-19 outbreak in China.

Methods

Study setting and participants

This cross-sectional comparative study was conducted between October 13 and 22, 2020. This was considered a suitable period for investigating the post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms because the first outbreak was brought under control in China in May 2020 [19]. Following previous studies [20,21,22], to minimize the risk of COVID-19 transmission, participants were recruited and assessed using the online WeChat-based QuestionnaireStar program (Changsha Haoxing Information Technology Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) based on convenient sampling. A Quick Response (QR) code linked to the invitation and assessments was disseminated to all public hospitals in Beijing with the help of the Beijing Hospital Authority via WeChat, which is the most popular social network application in China, with around 1.2 billion monthly active users [23]. All clinicians who were working in public hospitals in Beijing needed to regularly report personal health status with WeChat during the pandemic; therefore, all were presumed to be WeChat users.

To be eligible, participants needed to meet the following criteria: (1) aged 18 years or older; (2) were clinicians working in public hospitals in Beijing during the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) provided online electronic informed consent. The study was conducted on a voluntary and confidential basis, and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anding Hospital.

Data collection and assessment tools

A data collection form was used to collect demographic information, including age, gender, education level, occupation (e.g., doctors, nurses, medical technician, and others), personal annual income, and marital status. COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians were defined as those who volunteered to work in the medical support team in Hubei province in early 2020 (epicenter during the first COVID-19 outbreak in China) or directly cared for COVID-19 patients in local hospitals in Beijing since the COVID-19 outbreak. Clinicians who did not provide care for COVID-19 patients since during the pandemic were defined as the “non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians”.

The severity of depressive symptoms was assessed using the validated Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9), which consists of 9 items, and each scores from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day) [24, 25]. A higher score represents more severe depression [26]. The psychometric properties of PHQ-9 Chinese version have been validated in Chinese populations [27, 28]. Participants were classified as “having depression” (depression hereafter) if their PHQ-9 total score was ≥5 [26].

The severity of anxiety symptoms was assessed using the validated Chinese version of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale—7 items (GAD-7), which consists of 7 items, and each scores from 0 (not at all) to 3 (almost every day) [29]. The total score of GAD-7 ranges from 0 to 21, with a higher score indicating more severe anxiety [29]. The GAD-7 Chinese version has been validated in the Chinese population with good psychometric properties [30, 31]. Participants were classified as “having anxiety” (anxiety hereafter) if their GAD-7 total score was ≥5 [29].

The 7-item Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) was used to evaluate the severity of insomnia symptoms. Each item is scored from 0 (none/very satisfied) to 4 (very severe/very dissatisfied), with the total score from 0 to 28 [32]. The Chinese version of ISI showed satisfactory psychometric properties [33,34,35]. Participants were classified as “having insomnia” if their ISI total score was ≥8 [32].

Workplace violence (WPV) experienced by clinicians since the COVID-19 outbreak was evaluated with the 10-item Chinese version of the Workplace Violence Scale [36]. This scale covers various forms of violence, including four items on psychological violence (including but not limited to verbally abusing, disparaging, scolding, insulting, threats in person or by letter), and six items on physical violence (including physical attacks regardless of the consequence severity, as well as sexual violence) [36]. Each item is rated by a 4-point scale regarding the violence frequency ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (more than three times) [36]. Participants were considered as “having experienced WPV” if he or she reported any type of psychological or physical violence since the COVID-19 outbreak.

Global QOL was assessed with the first two items of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire—brief version (WHOQOL-BREF), with a higher score representing higher QOL [37, 38]. The Chinese version of WHOQOL-BREF has been validated in the Chinese population with good psychometric properties [39, 40].

Statistical analyses

Propensity score matching

Due to different demographic characteristics between the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians in this study, the optimal fixed ratio matching based on propensity scores was used to identify comparable COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians with a matching ratio of 1:1.

The propensity score is the probability of a participant being assigned to a particular group (i.e., COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians in this study), calculated by a logistic regression model based on a given set of observed covariates (i.e., confounders) [41]. The propensity score matching procedure would match each participant in the COVID-19 treating frontline group with one non-COVID-19 treating frontline participant that has a similar value of the propensity score, thereby balancing the potential confounders between the two groups [41, 42]. The propensity score analysis could help reduce bias in research results by minimizing the confounding effects caused by unmatched demographic characteristics [42].

Confounders refer to variables that affect both the outcome variable and the grouping variable [43,44,45]; the potential confounders matched in the propensity score model are selected based on the variable-grouping relationships and the variable-outcome relationships [42, 44]. In this study, the variable-grouping relationships and the variable-outcome relationships were assessed using independent two-sample t-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and chi-square tests as appropriate. Confounders were selected based on an expert consensus and the findings of previous studies in the propensity score model [42, 46, 47].

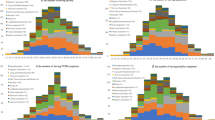

The balance of demographic characteristics after matching was assessed using standardized differences [42, 48,49,50]. To achieve a good matching balance, the absolute value of standardized difference was preferentially <0.1 [48, 51,52,53], with a minimum requirement of <0.25 [54, 55]. Mirror histograms were used to display the distributions of the propensity scores in the COVID-19 treating and the non-COVID-19 treating groups before and after matching.

Univariable analyses

In univariable analyses before and after matching, the demographic and clinical characteristics between the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating clinicians were compared using independent two-sample t-tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, and chi-square tests as appropriate. In the matched study sample, demographic characteristics that were significant in the univariable analyses were adjusted for in multivariable analysis models.

Multivariable analyses

In the matched study sample, the generalized linear model (GLM) was used to assess the differences in PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI total scores, and QOL between the COVID-19 treating and the non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians while adjusting for the demographic characteristics that were still significant in the univariable analyses after matching.

All data analyses were conducted using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) OnDemand for Academics (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The core SAS procedures implemented in this study were the PSMATCH procedure and the GENMOD procedure. Two-tailed p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the whole sample

Altogether, 260 COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians and 1473 non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians participated in this survey and completed the assessment. COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians were statistically different in age, sex, occupation composition, education level, and marital status (all p values < 0.05; Supplementary Table 1).

Potential confounder selection for propensity score matching

According to the preliminary results of the variable-grouping and the variable-outcome relationships (Supplementary Tables 1, 2), occupation, education level, and marital status of the clinicians were selected as the potential confounders, all of which were matched in the propensity score model. Additionally, since age and sex were the most commonly used confounders in previous studies [44, 56,57,58,59] and considerably associated with mental health status and QOL [60, 61], age and sex were also selected for matching in the propensity score model.

Propensity score matching

The propensity score matching procedure identified 260 comparable COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians in each group, composing a matched study sample of 520 participants. The standardized difference in the propensity scores between the matched two groups was 0.03, indicating that the matching procedure achieved a good balance. The absolute standardized differences of age, sex, occupation, education level, and marital status were all <0.1 (Table 1), showing that a good matching balance was achieved in each potential confounder.

The distributions of propensity scores before and after matching are shown in Fig. 1. Visual inspection of Fig. 1 found that the symmetry of propensity scores in the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline groups greatly improved after matching, further confirming the comparability between the two matched groups.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the matched sample

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the matched two samples are shown in Table 1. Univariable analyses revealed that the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians and their matched non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts were comparable in age, sex, occupation, education level, personal annual income, and marital status (all p values > 0.05).

There were no significant differences between the COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians in terms of the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI total scores (all p values >0.05), while the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians had higher QOL scores than the non-COVID-19 treating frontline group (t = −2.5, p = 0.015). Furthermore, the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians experienced less frequent WPV than their non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts (13.8 vs. 6.5%; χ2 = 7.6, p = 0.006).

Multivariable analyses

WPV during the COVID-19 outbreak was significantly associated with depression, anxiety, insomnia, and QOL scores (all p values < 0.05; Table 2). After adjusting for WPV, COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians still had higher QOL scores than their non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts (b = 0.3, 95% CI: 0.01–0.5, p = 0.042; Table 2). GLM analyses showed that work experience as COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians was not significantly associated with PHQ-9, GAD-7, and ISI total scores (all p values > 0.05; Table 2).

Discussion

This comparative study found that the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians had better QOL than their matched non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts after the first COVID-19 outbreak in China but did not find any significant group difference in terms of depression, anxiety, and insomnia symptoms.

To date, there have been no published studies that compared post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms and QOL between COVID-19 treating and non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians. Numerous studies on psychological responses to COVID-19, all of which were conducted before May 2020, found that COVID-19 treating frontline health workers were more likely to have lower QOL [62] and greater mental health problems, such as depression, anxiety, sleep problems, and PTSS, compared to their non-COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts [10,11,12,13,14, 63,64,65,66].

Following the first COVID-19 outbreak, COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians in China were provided with mental health, social and financial support. On February 22, 2020, the Central Leading Group for Responding to the COVID-19 Pandemic in China issued an announcement regarding support for COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [67]. Measures to improve COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians’ welfare were proposed, including increased wages, opportunities for occupational promotion, improved work-related injury insurance, flexible rotating clinical work, additional support for families of COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians, and provision of psychological counseling services. As a result, these measures may have supported the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians and offset the severity of post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms and improved their QOL. Additionally, some private-owned enterprises also provided financial supports for COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [68, 69]. University students also volunteered to provide free tutorials for the children of COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [70]. All the above-mentioned measures could have partly reduced the risk of post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms.

Several qualitative studies [71,72,73,74] found that COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians generally experienced three psychological phases during their work in the anti-pandemic frontline. The first phase is “duty and obligation that you cannot avoid”, in which clinicians volunteered to the frontline medical support team due to their occupational duties to take responsibility for patients’ health and well-being. The second phase is “physical and emotional exhaustion” due to heavy workload, unfamiliar working environment, wearing heavy personal protective equipment (PPE), loneliness, and fear of being infected. The third phase is “energy renewal, pride, and personal growth”, in which COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians gained psychological resilience, professional pride and recognition from colleagues, family members, and the public, gratitude from patients, and financial support from the government. Previous studies that reported worse mental health and decreased QOL among COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians compared to the non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [10,11,12,13,14, 63,64,65,66] were mostly conducted during the initial COVID-19 outbreak (earlier than April 2020), which is aligned with the second phase of the psychological experience. In this study, the lack of severity in terms of post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms among the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians could be partly because their experience was evolving into the third phase of the psychological experience.

Two possible factors could explain the lower QOL among non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians in this study. Non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians had less access to the medical information on the SARS-CoV-2 and less training on infection control measures compared to the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [75], which could reduce their confidence in combating the novel virus. Additionally, during the initial COVID-19 outbreak, the lack of PPE for clinicians not working in the anti-pandemic frontline may have led to an increased fear, negative psychological response, and decrease perceived QOL in non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians. One cross-sectional comparative study conducted in May 2020 in Malaysia found that non-COVID-19 treating frontline healthcare providers had experienced higher levels of depression, anxiety, and trauma compared to their COVID-19 treating frontline counterparts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic [76,77,78].

WPV was independently associated with more severe stress, anxiety, burnout [61, 79], and lowered global QOL [61]. The frequency of WPV experience in this study was considerably lower than that (1-year prevalence of WPV: 62.4%) reported in a meta-analysis conducted in China [79]. This may be attributed to several reasons. First, the timeframe of WPV experience in this study was “since the COVID-19 outbreak” (i.e., less than 1 year), while the meta-analysis used a 1-year timeframe [79]. Second, the meta-analysis was conducted in 2017. In recent years, the prevalence of WPV has gained considerable attention in China, and some effective measures have been adopted; for instance, mandatory security inspections before entering tertiary hospitals and lawsuits against perpetrators of WPV [80, 81]. Finally, in the guidelines for comprehensive measures to protect and care for COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians [67], creating a safer working environment for clinicians was listed as one of the priorities.

The strengths of this study included the matched demographic characteristics using the propensity score matching method. However, several limitations should be noted. First, due to the cross-sectional nature, this study could not make any inferences regarding the change in mental health symptoms over time in either COVID-19 treating or non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians. Second, the data were collected based on self-report; therefore, the possibility of recall bias could not be excluded. Third, for logical reasons, some factors associated with mental health symptoms, such as social support, were not measured. Fourth, this comparative study was based on convenient sampling, and the response rate could not be accurately estimated. Additionally, no data were collected on the general population, therefore, a direct comparison of mental health symptoms between the study sample and the general population during the same period could not be made.

In conclusion, this study did not find more severe post-COVID-19 mental health symptoms in COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians compared to non-COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians. It is possible that the implementation of timely and appropriate mental health, social and financial supports could have prevented the worsening of mental health symptoms among the COVID-19 treating frontline clinicians after the first COVID-19 outbreak in China.

References

World Health Organization. Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. 2020. https://www.whoint/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-it. Accessed 11 Feb 2020.

World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19-11 May 2020. 2020. https://www.whoint/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19–11-march-2020. Accessed 11 March 2020.

Johns Hopkins University. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). 2020. https://www.coronavirusjhuedu/maphtml. Accessed 25 Jan 2022.

Baud D, Qi X, Nielsen-Saines K, Musso D, Pomar L, Favre G. Real estimates of mortality following COVID-19 infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:773.

Hasan MN, Haider N, Stigler FL, Khan RA, McCoy D, Zumla A, et al. The global case-fatality rate of COVID-19 has been declining since May 2020. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;104:2176–84.

China Daily. Chongqing sends medical staff, oranges to aid epidemic control in Hubei. 2020. https://www.chinadailycomcn/regional/chongqing/liangjiang/2020-02/11/content_37533525htm. Accessed 11 Feb 2020.

City of Zhuhai. More Zhuhai medics and supplies en route to Hubei. 2020. http://www.cityofzhuhaicom/2020-02/13/c_451752htm. Accessed 13 Feb 2020.

Xinhua Net. With the help of more than 20,000 medical staff from other areas, could the tension in Hubei hospitals be relieved? (in Chinese). 2020. http://www.xinhuanetcom/2020-02/13/c_1125570509htm. Accessed 13 Feb 2020.

Xiang YT, Jin Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q, Zhang L, Cheung T. Tribute to health workers in China: a group of respectable population during the outbreak of the COVID-19. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16:1739–40.

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976.

Alshekaili M, Hassan W, Al Said N, Al Sulaimani F, Jayapal SK, Al-Mawali A, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes across healthcare settings in Oman during COVID-19: frontline versus non-frontline healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e042030.

Cai Q, Feng H, Huang J, Wang M, Wang Q, Lu X, et al. The mental health of frontline and non-frontline medical workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: A case-control study. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:210–5.

Trumello C, Bramanti SM, Ballarotto G, Candelori C, Cerniglia L, Cimino S, et al. Psychological adjustment of healthcare workers in Italy during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences in stress, anxiety, depression, burnout, secondary trauma, and compassion satisfaction between frontline and non-frontline professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:8358.

Zhang X, Zhao K, Zhang G, Feng R, Chen J, Xu D, et al. Occupational stress and mental health: a comparison between frontline medical staff and non-frontline medical staff during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:555703.

Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, et al. Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1924–32.

Ghebreyesus TA. World Health Organization warns: Coronavirus remains ‘extremely dangerous’ and ‘will be with us for a long time’. 2020. https://www.cnbccom/2020/04/22/world-health-organzation-warns-coronavirus-will-be-with-us-for-a-long-timehtml. Accessed 22 April 2020.

Tanabe K. Society coexisting with COVID-19. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41:988–9.

Kathirvel N. Post COVID-19 pandemic mental health challenges. Asian J psychiatry. 2020;53:102430.

DX Doctor. COVID-19 global pandemic real-time report (in Chinese). 2021. https://www.ncovdxycn/ncovh5/view/pneumonia. Accessed 22 April 2021.

Huang L, Lei W, Xu F, Liu H, Yu L. Emotional responses and coping strategies in nurses and nursing students during Covid-19 outbreak: a comparative study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0237303.

Liu J, Zhu Q, Fan W, Makamure J, Zheng C, Wang J. Online mental health survey in a Medical College in China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:459.

Li M, Liu L, Yang Y, Wang Y, Yang X, Wu H. Psychological impact of health risk communication and social media on college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e20656.

China Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT). WeChat employment impact report 2019-2020 (in Chinese). 2020. http://www.caictaccn/kxyj/qwfb/ztbg/202005/t20200514_281774htm. Accessed 1 May 2020.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Chen MM, Sheng L, Qu S. Diagnostic test of screening depressive disorder in general hospital with the patient health questionnaire (in Chinese). J Chin Ment Health. 2015;29:241–5.

Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hospital Psychiatry. 2014;36:539–44.

Xu Y, Wu HS, Xu YF. The application of patient health questionnaire 9 in community elderly population: reliability and validity. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2007;19:257–9+76.

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7.

Zeng Q-Z, He Y-L, Liu H, Miu J-M, Chen J-X, Xu H-N, et al. Reliability and validity of Chinese version of generalized anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale in screening anxiety disorder in outpatients from traditional Chinese internal department (in Chinese). Chin Ment Health J. 2013;27:163–8.

He X-Y, Li C-B, Qian J, Cui H-S, Wu W-Y. Reliability and validity of a generalized anxiety disorder scale in general hospital outpatients (in Chinese). Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2010;22:200–3.

Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307.

Yu DS. Insomnia severity index: psychometric properties with Chinese community-dwelling older people. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66:2350–9.

Li E-Z, Li W-X, Xie Z-T, Zhang B. The validity and reliability of severe insomnia index scale (in Chinese). 10th Annual Conference of Chinese Sleep Research Society; Harbin, Heilongjiang: Chinese Sleep Research Society; 2018. p. 154.

Bai C-J, Ji D-H, Chen L-X, Li L, Wang C-X. Reliability and validity of insomnia severity index scale in clinical insomnia patients (in Chinese). Chin J Practical Nurs. 2018;34:2182–6.

Chen Z-H, Wang S-Y, Jing C-X. Prevalence of workplace violence in staff of two hospitals in Guangzhou (in Chinese). Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2003;37:358–60.

Skevington SM, Tucker C. Designing response scales for cross-cultural use in health care: data from the development of the UK WHOQOL. Br J Med Psychol. 1999;72:51–61.

The WHOQOL GROUP. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–8.

Fang J-Q, Hao Y-T, Li C-X. Reliability and validity for Chinese version of WHO quality of life scale (in Chinese). Chinese. J Ment Health. 1999;13:203–5+7.

Xia P, Li N, Hau KT, Liu C, Lu Y. Quality of life of Chinese urban community residents: a psychometric study of the mainland Chinese version of the WHOQOL-BREF. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:37.

Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55.

Austin PC. A critical appraisal of propensity-score matching in the medical literature between 1996 and 2003. Stat Med. 2008;27:2037–49.

VanderWeele TJ, Shpitser I. On the definition of a confounder. Ann Stat. 2013;41:196–220.

Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Stürmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1149–56.

Schulz KF, Grimes DA. The Lancet handbook of essential concepts in clinical research. Amsterdam, Elsevier; 2006.

Ali MS, Prieto-Alhambra D, Lopes LC, Ramos D, Bispo N, Ichihara MY, et al. Propensity score methods in health technology assessment: principles, extended applications, and recent advances. Front Pharm. 2019;10:973.

Austin PC. Propensity-score matching in the cardiovascular surgery literature from 2004 to 2006: a systematic review and suggestions for improvement. J Thorac Cardiovascular Surg. 2007;134:1128.e3–35.

Yao XI, Wang X, Speicher PJ, Hwang ES, Cheng P, Harpole DH, et al. Reporting and guidelines in propensity score analysis: a systematic review of cancer and cancer surgical studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw323.

Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Matching as nonparametric preprocessing for reducing model dependence in parametric causal inference. Political Anal. 2007;15:199–236.

Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. Misunderstandings among experimentalists and observationalists: balance test fallacies in causal inference. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 2007;17:481–502.

Normand ST, Landrum MB, Guadagnoli E, Ayanian JZ, Ryan TJ, Cleary PD, et al. Validating recommendations for coronary angiography following acute myocardial infarction in the elderly: a matched analysis using propensity scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:387–98.

Austin PC. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–107.

Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, Normand SL, Streiner DL, Austin PC, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2 Assess potential confounding. BMJ. 2005;330:960–2.

Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci. 2010;25:1–21.

Rubin DB. Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol. 2001;2:169–88.

Uphoff EP, Lombardo C, Johnston G, Weeks L, Rodgers M, Dawson S, et al. Mental health among healthcare workers and other vulnerable groups during the COVID-19 pandemic and other coronavirus outbreaks: a rapid systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0254821.

Hao Q, Wang D, Xie M, Tang Y, Dou Y, Zhu L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of mental health problems among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:567381.

Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7.

Marvaldi M, Mallet J, Dubertret C, Moro MR, Guessoum SB. Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;126:252–64.

Zhao YJ, Zhang SF, Li W, Zhang L, Cheung T, Tang YL, et al. Mental health status and quality of life in close contacts of COVID-19 patients in the post-COVID-19 era: a comparative study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:505.

Xie XM, Zhao YJ, An FR, Zhang QE, Yu HY, Yuan Z, et al. Workplace violence and its association with quality of life among mental health professionals in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;135:289–93.

Tran TV, Nguyen HC, Pham LV, Nguyen MH, Nguyen HC, Ha TH, et al. Impacts and interactions of COVID-19 response involvement, health-related behaviours, health literacy on anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life among healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e041394.

Parthasarathy R, Ts J, K T, Murthy P. Mental health issues among health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic - A study from India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58:102626.

Su Q, Ma X, Liu S, Liu S, Goodman BA, Yu M, et al. Adverse psychological reactions and psychological aids for medical staff during the COVID-19 outbreak in china. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:580067.

Zhou Y, Ding H, Zhang Y, Zhang B, Guo Y, Cheung T, et al. Prevalence of poor psychiatric status and sleep quality among frontline healthcare workers during and after the COVID-19 outbreak: a longitudinal study. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:223.

Di Tella M, Romeo A, Benfante A, Castelli L. Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. J Eval Clin Pr. 2020;26:1583–7.

Central Leading Group for Responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. Notice on the comprehensive implementation of several measures to further protect and care for frontline medical personnel (in Chinese). 2020. http://www.govcn/zhengce/content/2020-02/23/content_5482345htm. Accessed 22 Feb 2020.

China Daily. Caterers express gratitude to medical workers. 2020. https://www.globalchinadailycomcn/a/202003/23/WS5e787a9aa31012821728150ehtml. Accessed 23 March 2020.

China Daily. Free movies offered as thanks to medical workers. 2020. https://www.chinadailycomcn/a/202008/28/WS5f488b3da310675eafc5621bhtml. Accessed 28 Aug 2020.

China Daily. College students provide free tutoring to children of medical staff. 2020. https://globalchinadailycomcn/a/202002/18/WS5e4b7f7aa310128217278680html. Accessed 18 Feb 2020.

Liu Q, Luo D, Haase JE, Guo Q, Wang XQ, Liu S, et al. The experiences of health-care providers during the COVID-19 crisis in China: a qualitative study. Lancet. Glob Health. 2020;8:e790–e8.

Sun N, Wei L, Shi S, Jiao D, Song R, Ma L, et al. A qualitative study on the psychological experience of caregivers of COVID-19 patients. Am J Infect Control. 2020;48:592–8.

Zhang Y, Wei L, Li H, Pan Y, Wang J, Li Q, et al. The psychological change process of frontline nurses caring for patients with COVID-19 during its outbreak. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2020;41:525–30.

Lee N, Lee HJ. South Korean nurses’ experiences with patient care at a COVID-19-designated hospital: growth after the frontline battle against an infectious disease pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9015.

Tan BYQ, Chew NWS, Lee GKH, Jing M, Goh Y, Yeo LLL, et al. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in Singapore. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:317–20.

Mohd Noor N, Che Yusof R, Yacob MA. Anxiety in frontline and non-frontline healthcare providers in Kelantan, Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:861.

Norhayati MN, Che Yusof R, Azman MY. Vicarious traumatization in healthcare providers in response to COVID-19 pandemic in Kelantan, Malaysia. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0252603.

Norhayati MN, Che Yusof R, Azman MY. Depressive symptoms among frontline and non-frontline healthcare providers in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Kelantan, Malaysia: a cross sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0256932.

Lu L, Dong M, Wang SB, Zhang L, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against health-care professionals in China: a comprehensive meta-analysis of observational surveys. Trauma Violence Abus. 2020;21:498–509.

Zhao X-Y. China’s large hospitals are entering the era of security inspection in an all-round way (in Chinese). 2021. https://www.163.com/dy/article/GJ3GE5CS05149RLM.html. Accessed 5 Sep 2021.

Portal of the PRC. Memorandum of implementing joint punishment and cooperation on persons who seriously endanger the normal medical order (in Chinese). 2018. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2018-10/17/content_5331603.htm. Accessed 17 Oct 2018.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Changshun Xu, Mr. Cunliang Wang and Mr. Yan Li and other staff in Beijing Hospital Authority who contributed to this study. We also thank all clinicians who participated in this study. The study was supported by the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (PX2018063), Beijing Municipal Science & Technology Commission (Z181100001718124), Beijing Talents Foundation (2017000021469G222), and the University of Macau (MYRG2019-00066-FHS; MYRG2022-00187-FHS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study Design: SS and Y-TX. Collection, analysis, and interpretation of data: Y-JZ, XX, TT, QW, SL, ZW, TC, ZS, CHN, and SS. Drafting of the manuscript: Y-JZ, Y-LT, and Y-TX. Critical revision of the manuscript: CHN. Approval of the final version for publication: All the authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, YJ., Xing, X., Tian, T. et al. Post COVID-19 mental health symptoms and quality of life among COVID-19 frontline clinicians: a comparative study using propensity score matching approach. Transl Psychiatry 12, 376 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02089-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02089-4