Abstract

Study design

Prospective, multi-centered, observational.

Objectives

To characterize the relationship between psychosocial aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and patient-reported bladder outcomes.

Setting

Multi-institutional sites in the United States, cohort drawn from North America.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional analysis of data collected as part of the multicenter, prospective Neurogenic Bladder Research Group Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Registry. Outcomes were: Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score (NBSS), Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score Satisfaction (NBSS-Satisfaction), and SCI-QoL Bladder Management Difficulties (SCI-QoL Difficulties). Adjusted multiple linear regression models were used with variables including demographic, injury characteristics, and the following psychosocial HRQoL measures; SCI-QoL Pain Interference (Pain), SCI-QoL Independence, and SCI-QoL Positive Affect and Well-being (Positive Affect). Psychosocial variables were sub-divided by tertiles for the analysis.

Results

There were 1479 participants, 57% had paraplegia, 60% were men, and 51% managed their bladder with clean intermittent catheterization. On multivariate analysis, higher tertiles of SCI-QoL Pain were associated with worse bladder symptoms, satisfaction, and bladder management difficulties; upper tertile SCI-QoL Pain (NBSS 3.8, p < 0.001; NBSS-satisfaction 0.6, p < 0.001; SCI-QoL Difficulties 2.4, p < 0.001). In contrast, upper tertiles of SCI-QoL Independence and SCI-QoL Positive Affect were associated with improved bladder-related outcomes; upper tertile SCI-QoL Independence (NBSS −2.3, p = 0.03; NBSS-satisfaction −0.4, p < 0.001) and upper tertile SCI-QoL Positive Affect (NBSS −2.8, p < 0.001; NBSS-satisfaction −0.7, p < 0.001; SCI-QoL Difficulties −0.7, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In individuals with SCI, there is an association between psychosocial HRQoL and bladder-related QoL outcomes. Clinician awareness of this relationship can provide insight into optimizing long-term management after SCI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the general U.S. population, ~282,000 people are living with spinal cord injury (SCI) [1]. The estimated annual incidence of SCI is about 17,000 cases, with trauma being the most common cause amongst all age groups [1]. The resulting neurological injury presents a wide range of challenges, with considerable long-term disability. Some studies on individuals with SCI have identified loss of normal bladder and bowel function as a significant source of both physical morbidities, as well as psychologic stress [2,3,4]. Furthermore, several studies have shown an association between psychosocial aspects of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (such as pain interference, positive affect and well-being, independence) and overall quality of life (QoL) following SCI [5,6,7,8,9].

In our previous work, we have established relationships between demographic factors, bladder management method, injury characteristics, SCI complications and bladder-related symptoms and satisfaction [10,11,12,13]; however, very little is known about how psychosocial aspects of HRQoL influence bladder-related QoL. Studies have established relationships between psychosocial aspects of HRQoL factors and general QoL outcomes following SCI and how psychosocial factors such as depression, chronic pain, and independence all can influence the way people perceive biologic function [5, 7, 9]. A good example of this is the association between post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and lower urinary tract symptoms in veterans [14].

In this study, our objective was to examine the relationship between psychosocial aspects of HRQoL and bladder-related QoL using validated neurogenic bladder patient-reported outcome measures and measures of pain, independence, and well-being. Understanding how psychosocial aspects of HRQoL are associated with bladder symptoms and satisfaction is important and may need to be considered in future studies of how to improve bladder function and satisfaction. We hypothesized that psychosocial aspects of HRQoL factors would demonstrate significant associations with bladder symptoms and satisfaction in individuals with SCI.

Methods

We used the Neurogenic Bladder Research Group (NBRG) SCI Registry to conduct a cross-sectional study of participants. The NBRG SCI Registry (https://www.NBRG.org) was a multicenter, prospective, observational study conducted through the Universities of Michigan, Minnesota and Utah, which measured neurogenic bladder-related QoL after SCI. The study was conducted in multiple settings within each of these sites, including but not limited to rehabilitation hospitals, nursing facilities, physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics and urology clinics. Participants were recruited throughout the United States and Canada. Detailed information regarding study protocol, recruitment methods, duration, and study aims have previously been published [15]. Eligibility requirements included: age ≥ 18 years, English speaking, and a diagnosis of acquired SCI (i.e., traumatic injury, spinal cord bleed/abscess or stroke, spinal cord tumor without active malignancy, iatrogenic causes, transverse myelitis and miscellaneous disorders such as cauda equina syndrome). Participants with congenital conditions (e.g., cerebral palsy, myelomeningocele) or progressive SCI (e.g., multiple sclerosis, neurologic disorders) were excluded from the study. Participants were enrolled in the study over a span of 1.5 years, ending on June 30th, 2017. Enrollment interview, with study coordinators, included questions that assessed participant’s baseline demographics, medical and surgical history, injury characteristics, bladder management over time, and complications. Participants then answered a panel of questionnaires that included information about bladder symptoms, satisfaction, bowel dysfunction, chronic pain, mobility, independence, depression, and satisfaction with aspects of social participation.

Primary outcome measures

-

i.

Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score (NBSS): the NBSS is a tool developed for people with neurogenic bladder and SCI. Its 22 questions assess urinary symptoms including voiding, incontinence and storage as well as urinary complications. The scores range from 0 to 74 with lower scores indicating less symptoms [11, 16, 17].

-

ii.

Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score – Satisfaction (NBSS-satisfaction): this is the separately scored final question of the NBSS (range 0–4) which assess satisfaction with urinary function. It is phrased - “If you had to live the rest of your life with the way your bladder (or urinary reservoir) currently works, how would you feel?” (0-pleased, 1-mostly satisfied, 2-equally satisfied and unsatisfied/mixed, 3-mostly unsatisfied, 4-unhappy) [11, 16, 17].

-

iii.

Spinal Cord Injury Quality of Life Bladder Management Difficulties (SCI-QoL Difficulties): this is one item bank from SCI-QoL measurement system. It specifically assesses the ability to carry out a bladder program, as well as concerns about incontinence and impact on daily life. The SCI-QoL Difficulties uses computer adaptive testing and is scored from 0 to 100 with a median of 50. Similar to the NBSS, lower scores indicate less bladder difficulties [18].

Analysis variables

Participant variables that were analyzed included: (1) demographic variables: age, gender, obesity (body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2), education level (bachelor’s degree or higher), (2) injury characteristics: level of injury (tetraplegia i.e., cervical level 1–8 vs. paraplegia i.e., thoracic level 1 and below, including sacral levels and cauda equina), years since injury, primary bladder management (clean intermittent catheterization [CIC], chronic indwelling catheter [IDC, Foley catheter or suprapubic cystotomy], surgery [conduit urinary diversions, continent catheterizable pouch, augmentation cystoplasty with or without catheterizable channel], or spontaneous voiding [credé voiding, condom catheter, volitional voiding into a toilet, leaking into diapers]), number of self-reported urinary tract infections (UTI) in the last year (categorical: 0, 1–3, 4 or more), severe bowel dysfunction (Neurogenic Bowel Dysfunction (NBD) Score > 14) [15], and (3) measures of psychosocial aspects of HRQoL: SCI-QoL Pain Interference (Pain), SCI-QoL Independence, and SCI-QoL Positive Affect and Well-being (Positive Affect).

Measure of psychosocial aspects of HRQoL

For measures of psychosocial aspects of HRQoL, we considered nine validated measures of psychosocial and physical experience after SCI. Many of these measurement tools are from the SCI-QoL measurement system and have similar methodology to the SCI-QoL Difficulties (one of the primary outcome measures). They use computer adaptive testing and are calibrated to a mean of 50. The nine measurement tools were: SCI-QoL Fine Motor, SCI-QoL Independence, SCI-QoL Basic Mobility, SCI-QoL Pain, SCI-QoL Positive Affect, SCI-QoL Self-Care, and SCI-QoL Satisfaction with Social Roles and Activities, Short Form Survey (SF-12) Mental, and the SF-12 Physical. The SF-12 is an instrument made up of 12 questions selected from the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) 36-item Short-Form Survey (SF-36) [19]. The 12 questions were combined, scored and weighted to create two scales that assess mental and physical functioning and overall health-related QoL [20]. Since some of these psychosocial aspects of HRQoL measure similar concepts and there was a recognized likelihood of correlations between some of these factors, to minimize correlations when selecting measures for the study, a Pearson correlation matrix was created between each of these factors. We considered pairs of factors with a significant correlation with a magnitude >0.5 to have a relevant correlation. After review of the correlation matrix, we selected those factors with the least correlation that had face value to investigators in measuring concepts we felt were important within the psychosocial domain of experience. Complete data for the correlation matrix can be found in Table 1.

The three measurement tools of the psychosocial aspects of HRQoL with the least correlation with one another were SCI-QoL Pain interference, which assesses self-reported consequences of pain on everyday life [21, 22], SCI-QoL Independence, which assesses perceptions of personal independence, ability to communicate needs with others and a sense of control over one’s life [22,23,24], and SCI-QoL Positive Affect, which assesses aspects that relate to a sense of well-being, life satisfaction and sense of purpose [22, 25, 26].

Statistical analysis

Some participants had incomplete data and were not included in the analysis. There were 1358 participants with non-missing values for all our adjustment variables for NBSS-total and NBSS-satisfaction and 1355 participants for SCI-QoL Difficulties. All statistical analysis was performed using SAS Software, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC. The associations between psychosocial aspects of HRQoL (SCI-QoL Pain, SCI-QoL Independence and SCI-QoL Positive Affect) and primary outcomes (NBSS-total, NBSS-satisfaction and SCI-QoL Difficulties) were assessed using multiple linear regression models. Measures of the psychosocial aspects of HRQoL were separated into tertiles to better illustrate associated changes with bladder-related outcome measures. For continuous variables such as age and years since injury, the values were scaled by a factor of 10, thus changes in outcome measures represent changes associated with 10 years of change rather than 1 year of change for those variables. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.), and categorical variables presented as frequency (percent). Using the central limit theorem, we assumed that the sample means were approximately normally distributed.

Collinearity between all variables and psychosocial aspects of HRQoL factors were assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF) to determine whether there was any significant collinearity between the variables selected for inclusion in the multivariate regression model. A VIF value <2.5 was used as a threshold to indicate no significant collinearity between the variables in the model. Separate multiple linear regression models were used for all three measures of psychosocial aspects of HRQoL to observe how each measure was associated with bladder-related outcome measures, when controlling for additional participant characteristics (primary bladder management, level of injury, age, sex, years since injury, BMI, number of UTIs, severe bowel dysfunction and education level). In each model, the continuous scores for the measures of psychosocial aspects of HRQoL were replaced by tertiles (lower, middle and upper) and the Bonferroni correction was applied to the p values to adjust for multiple testing. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, representing 95% confidence level.

Results

Participant demographic and clinical characteristics

A total of 1479 participants were enrolled in the study; most were male (60.4%) and had paraplegia (57.0%). The mean age of participants was 44.8 ± 13.1 years and the mean time since injury was 14.6 ± 11.8 years. The most common primary bladder management method used was CIC (51.0%), followed by IDC (18.3%). Detailed baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Psychosocial aspects of HRQoL and bladder-related QoL

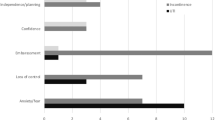

In the unadjusted analysis, there was no defined relationship between SCI-QoL Independence and bladder-related outcomes. However, both SCI-QoL Pain and SCI-QoL Positive Affect had significant association with all bladder-related outcome measures. As tertiles of SCI-QoL Pain increased, NBSS, NBSS-satisfaction, and SCI-QoL Difficulties worsened (increased, p < 0.001), indicating worse bladder-related symptoms and QoL. The reverse was observed with tertiles of SCI-QoL Positive Affect, where an increase in tertile was associated with better bladder-related symptoms and QoL i.e., lower NBSS score, NBSS-satisfaction score and SCI-QoL Difficulties score (p < 0.001). Results are shown in Table 3.

In the multivariable analysis, after adjusting for the analysis variables, SCI-QoL Pain and SCI-QoL Positive Affect maintained the same effect as seen in the unadjusted analysis on all three bladder-related outcome measures. The upper tertile of SCI-QoL Pain was associated with higher NBSS score (Beta 3.8 95% CI 2.5, 5.0, p < 0.001), NBSS-satisfaction score (Beta 0.6 95% CI 0.4, 0.7, p < 0.001) and SCI-QoL Difficulties score (Beta 2.4 95% CI 1.5, 3.4, p < 0.001), while the upper tertile of SCI-QoL Positive Affect was associated with lower NBSS score (Beta −2.8 95% CI −4.1, −1.6, p < 0.001), NBSS-satisfaction score (−0.7, 95% CI −0.8, −0.5, p < 0.001) and SCI-QoL Difficulties score (Beta −0.7, 95% CI −0.8, −0.5, p < 0.001). The upper tertile of SCI-QoL Independence was associated with lower NBSS score (Beta −2.3, 95% CI −3.7, −0.8, p = 0.03) and NBSS-satisfaction (Beta −0.4, 95% CI −0.6, −0.2, p < 0.001). The VIF measures were <2.5 indicating low collinearity in these analyses. These results are detailed in Table 4. Complete multivariable analysis for all SCI-QoL independence and SCI-QoL positive affect and well-being are shown in Tables 5 and 6.

Discussion

In this study, we assessed the impact of pain, independence, and well-being on patient-reported bladder symptoms and satisfaction. We adjusted for demographic, and injury specific factors that we know are associated with differences in patient-reported bladder outcomes [11] and still found strong associations with these psychosocial aspects of HRQoL and how individuals with SCI perceive their bladder symptoms and satisfaction. Pain was associated with worse bladder symptoms and satisfaction, while greater independence and a better positive affect and well-being were associated with less bladder symptoms and greater satisfaction with bladder function. This is an important observation given that objective symptoms may be perceived very differently by two individuals depending upon their overall mental and physical state.

Our study findings reveal that the presence or absence of pain is associated with bladder symptoms (NBSS) and patient satisfaction (NBSS-Satisfaction and SCI-QoL Difficulties). Individuals with lower pain interference had fewer bladder symptoms and felt more satisfied with their bladder function and management, even after controlling for patient and injury-related variables such as age, gender, time since injury and level of injury. In individuals with SCI, chronic pain can interfere with day-to-day life, which can affect overall satisfaction. This is consistent with previously published data that showed a negative relationship between pain and QoL amongst individuals with SCI [27, 28]. In addition, increased pain interference has been shown to be associated with having a greater number of other health conditions such as PTSD and depression in individuals with SCI [6, 29], which could also influence a person’s perception of their bladder symptoms. It is unclear how or why pain would have significant impact on bladder symptoms, as intuitively one would expect bladder symptoms to be related directly to actual bladder function and be a more objective measure. The results could be from a confounding factor we have not accounted for or that pain actually worsens participant’s bladder function.

We also found that having better positive affect and well-being is associated with fewer bladder symptoms and improved overall satisfaction with bladder function. Although this has not been measured in relation to bladder-related QoL, others have shown key associations between these themes and general QoL in individuals with SCI [7]. In the systemic review conducted by van Leeuwen, Kraaijeveld, Lindeman and Post, a person’s total perceived degree of control in life and positive feelings of purpose and self-worth were the most consistent determinants of QoL after SCI [30]. In addition, evidence from other studies on individuals with SCI have also revealed that, self-efficacy is a significant determinant of resilience [31, 32]. The explanation for the observed association between positive affect and well-being and bladder-related outcomes is not clear; however, perhaps those individuals with a very positive outlook are not bothered by their bladder symptoms and minimize their actual objective symptoms and the perception of their bladder’s impact on their life.

Interestingly, our data indicates that higher independence scores are significantly associated with better bladder satisfaction but have no effect on bladder symptoms and management difficulties. This outcome was unexpected; however, it may reflect the complex interaction between independence and QoL that is influenced by both adaptation to physical disabilities and mental functioning [30]. Although physical disability is an important factor of overall health, studies into its effect on QoL have had varying outcomes [9, 33], with only a weak relationship between physical disability and QoL demonstrated on a recent meta-analysis [34].

This study has methodological limitations that should be acknowledged. We used self-reported survey data, which makes it subject to inclusion and/or recall bias. For instance, those participants that had bladder problems may have been more likely to enroll in the study, to obtain additional information or in hopes of improving their bladder function. Inclusions bias may be especially relevant in a study of psychosocial aspects of HRQOL, as most study participants were sophisticated and entered the study via enrollment from Facebook. Recall of complex medical history is hard for even the most sophisticated person. In addition, we are unable to ascertain the nature of chronic pain, where it was located, whether it was directly related to the bladder or arose from more typical neuropathic pain after SCI. Another limitation of the study result lies in the clinical significance of differences in QoL measures due to the scale that was applied; for example, on the SCI-QoL Difficulties scale, a 1-point change may be statistically significant but may not have any clinical relevance. Changes in the NBSS and NBSS-satisfaction were often close to or >10% (compared to the referent) meeting the generally agreed upon axiom for clinically significant change for a patient-reported outcome measure; however, formal testing to determine the minimum clinical difference has not been done for these measurement tools. Finally, we measured association, so it is not possible to determine if there was a causative relationship between the psychosocial aspects of HRQoL and urinary symptom or satisfaction and the associations noted may indeed be due to unaccounted for confounders.

Conclusion

Our results show that independent of demographic and injury-related factors such as, level of injury, duration of injury, and bladder management method—pain, independence, and positive affect are all associated with better or worse bladder symptoms, satisfaction or both. Treatment efforts geared toward identifying and implementing rehabilitation services that decrease pain interference while improving independence and positive affect and well-being may help in optimizing bladder-related QoL after SCI.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

NSCISC. Spinal Cord Injury (SCI) Facts and Figures as a Glance. https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts%20and%20Figures%20-%202018.pdf.

Simpson LA, Eng JJ, Hsieh JT, Wolfe DL, Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Scire Research Team. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:1548–55.

Lo C, Tran Y, Anderson K, Craig A, Middleton J. Functional Priorities in Persons with Spinal Cord Injury: using Discrete Choice Experiments To Determine Preferences. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:1958–68.

Manns PJ, Chad KE. Components of quality of life for persons with a quadriplegic and paraplegic spinal cord injury. Qual Health Res. 2001;11:795–811.

Avluk OC, Gurcay E, Gurcay AG, Karaahmet OZ, Tamkan U, Cakci A. Effects of chronic pain on function, depression, and sleep among patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. Ann Saudi Med. 2014;34:211–6.

Etingen B, Miskevics S, LaVela SL. The Relationship Between Pain Interference and Psychosocial Well-Being Among Veterans With Spinal Cord Injuries/Disorders. J Neurosci Nurs. 2018;50:48–55.

Bhattarai M, Maneewat K, Sae-Sia W. Psychosocial factors affecting resilience in Nepalese individuals with earthquake-related spinal cord injury: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:60.

Kim S, Whibley D, Williams DA, Kratz AL. Pain Acceptance in People With Chronic Pain and Spinal Cord Injury: daily Fluctuation and Impacts on Physical and Psychosocial Functioning. J Pain. 2020;21:455–66.

Ekechukwu E, Ikrechero JO, Ezeukwu AO, Egwuonwu AV, Umar L, Badaru UM. Determinants of quality of life among community-dwelling persons with spinal cord injury: A path analysis. Niger J Clin Pr. 2017;20:163–9.

Theisen KM, Mann R, Roth JD, Pariser JJ, Stoffel JT, Lenherr SM, et al. Frequency of patient-reported UTIs is associated with poor quality of life after spinal cord injury: a prospective observational study. Spinal Cord. 2020;58:1274–81.

Myers JB, Lenherr SM, Stoffel JT, Elliott SP, Presson AP, Zhang C, et al. Patient Reported Bladder Related Symptoms and Quality of Life after Spinal Cord Injury with Different Bladder Management Strategies. J Urol. 2019;202:574–84.

Crescenze IM, Myers JB, Lenherr SM, Elliott SP, Welk B, Mph DO, et al. Predictors of low urinary quality of life in spinal cord injury patients on clean intermittent catheterization. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:1332–8.

Myers JB, Lenherr SM, Stoffel JT, Elliott SP, Presson AP, Zhang C, et al. The effects of augmentation cystoplasty and botulinum toxin injection on patient-reported bladder function and quality of life among individuals with spinal cord injury performing clean intermittent catheterization. Neurourol Urodyn. 2019;38:285–94.

Breyer BN, Cohen BE, Bertenthal D, Rosen RC, Neylan TC, Seal KH. Lower urinary tract dysfunction in male Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans: association with mental health disorders: a population-based cohort study. Urology 2014;83:312–9.

Patel DP, Lenherr SM, Stoffel JT, Elliott SP, Welk B, Presson AP, et al. Study protocol: patient reported outcomes for bladder management strategies in spinal cord injury. BMC Urol. 2017;17:95.

Welk B, Lenherr S, Elliott S, Stoffel J, Presson AP, Zhang C, et al. The Neurogenic Bladder Symptom Score (NBSS): a secondary assessment of its validity, reliability among people with a spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2018;56:259–64.

Welk B, Morrow S, Madarasz W, Baverstock R, Macnab J, Sequeira K. The validity and reliability of the neurogenic bladder symptom score. J Urol. 2014;192:452–7.

Tulsky DS, Kisala PA, Tate DG, Spungen AM, Kirshblum SC. Development and psychometric characteristics of the SCI-QOL Bladder Management Difficulties and Bowel Management Difficulties item banks and short forms and the SCI-QOL Bladder Complications scale. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:288–302.

John E, Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey- Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity.pdf. JSTOR. 1996;34:220–33.

Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Evidence Scire Research T. Spinal Cord Injury Research Evidence, SCIRE. https://scireproject.com/outcome-measures/outcome-measure-tool/short-form-36-sf-36/#1467983894080-2c29ca8d-88af.

Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, Chen WH, Choi S, Revicki D, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain 2010;150:173–82.

Spinal Injuries Database [Internet]. [cited July 31, 2020]. https://www.sralab.org/rehabilitation-measures.

Tulsky DS, Kisala PA, Victorson D, Tate DG, Heinemann AW, Charlifue S, et al. Overview of the Spinal Cord Injury-Quality of Life (SCI-QOL) measurement system. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:257–69.

Tulsky DS, Kisala PA, Victorson D, Choi SW, Gershon R, Heinemann AW, et al. Methodology for the development and calibration of the SCI-QOL item banks. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:270–87.

Bertisch H, Kalpakjian CZ, Kisala PA, Tulsky DS. Measuring positive affect and well-being after spinal cord injury: Development and psychometric characteristics of the SCI-QOL Positive Affect and Well-being bank and short form. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:356–65.

Tulsky DS, Kisala PA, Victorson D, Tate D, Heinemann AW, Amtmann D, et al. Developing a contemporary patient-reported outcomes measure for spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:S44–51.

Putzke JD, Richards SJ, Hicken BL, DeVivo MJ. Interference due to pain following spinal cord injury: important predictors and impact on quality of life. Pain. 2002;100:231–42.

Cuff L, Fann JR, Bombardier CH, Graves DE, Kalpakjian CZ. Depression, pain intensity, and interference in acute spinal cord injury. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2014;20:32–9.

Ullrich PM, Smith BM, Poggensee L, Evans CT, Stroupe KT, Weaver FM, et al. Pain and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms during inpatient rehabilitation among operation enduring freedom/operation iraqi freedom veterans with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;94:80–5.

van Leeuwen CM, Kraaijeveld S, Lindeman E, Post MW. Associations between psychological factors and quality of life ratings in persons with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:174–87.

Kilic SA, Dorstyn DS, Guiver NG. Examining factors that contribute to the process of resilience following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:553–7.

Driver S, Warren AM, Reynolds M, Agtarap S, Hamilton R, Trost Z, et al. Identifying predictors of resilience at inpatient and 3-month post-spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:77–84.

Goulet J, Richard-Denis A, Thompson C, Mac-Thiong JM. Relationships Between Specific Functional Abilities and Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;98:14–9.

Dijkers M. Quality of life after spinal cord injury: a meta analysis of the effects of disablement components. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:829–40.

Funding

This work was partially supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CER14092138). This investigation was supported by the University of Utah Study Design and Biostatistics Center, with funding in part from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant 5UL1TR001067-05 (formerly 8UL1TR000105 and UL1RR025764).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

OM was responsible for interpretation of results and paper writing. JH and AP were responsible for data analysis, result interpretation and paper revision. JTS, SE, BW, SL and JBM aided in study design, acquired data, and revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

I/we certify that all applicable institutional and government regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers/animals were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moghalu, O., Stoffel, J.T., Elliott, S. et al. Psychosocial aspects of health-related quality of life and the association with patient-reported bladder symptoms and satisfaction after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 59, 987–996 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00609-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-020-00609-x

This article is cited by

-

Determining health-related quality of life and health state utility values of recurrent urinary tract infections in women

International Urogynecology Journal (2023)

-

Catheter Use in Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction—Can Shared Decision-Making Help Us Serve Our Patients Better?

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2023)

-

Psychosocial Factors in Neurogenic Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction: Implications for Multidisciplinary Care

Current Bladder Dysfunction Reports (2022)

-

Editorial special edition neuro-urology

Spinal Cord (2021)