Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional study.

Objectives

To describe and compare mental health and life satisfaction between individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) and their partners 5 years after discharge from first inpatient rehabilitation; and to examine if injury severity moderates the association between individuals’ with SCI and their partners’ mental health and life satisfaction.

Setting

Dutch community.

Methods

Sixty-five individuals with SCI and their partners completed a self-report questionnaire. Main outcome measures were the mental health subscale of the Short-Form Health Survey and the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire.

Results

Levels of mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and partners were similar, with median scores of 76 and 4.8 versus 76 and 4.6, respectively. Moderate to strong correlations between individuals with SCI and their partners were found for the mental health (rS = 0.35) and life satisfaction scores (rS = 0.51). These associations were generally stronger in the subgroup of individuals with less severe SCI. Associations between scores on separate life domains ranged from negligible (0.05) to moderate (0.53). Individuals with SCI and their partners were least satisfied with their ‘sexual life’. Compared with their partners, individuals with SCI were significantly more satisfied in the domains ‘leisure situation’, ‘partnership relation’ and ‘family life’, and less satisfied in ‘self-care ability’.

Conclusions

This study showed similarities but also differences in mental health and life satisfaction between individuals with SCI and their partners. In clinical practice, attention on mental health and life satisfaction should, therefore, focus on different domains for individuals with SCI and partners.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) are confronted with challenges regarding their physical health [1, 2], mental health and life satisfaction [3], and social functioning [4]. Systematic reviews have estimated a prevalence of depressive mood and anxiety problems in this group of 22% and 27%, respectively [5, 6]. In general, life satisfaction is lower in individuals with tetraplegia compared to those with paraplegia, but no differences with respect to mental health were found [3]. Studies also report life satisfaction in people with SCI to be substantially lower compared to the general population [3]. However, people close to them, in particular their partners, also experience the impact of SCI, have to adapt their pre-injury lifestyle and to undertake a caregiving role and responsibilities [7, 8]. Partners often express ongoing feelings of anxiety, depression and low levels of life satisfaction [9,10,11,12].

It is conceivable that mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and their partners interact mutually. Insight in the reciprocal influences between individuals with SCI and their partners may therefore contribute to the professionals’ understanding of the complex situation of couples after SCI and may provide opportunities to support both individuals with SCI, their partners and together as a couple. Only two SCI studies on this topic were found. In a Turkish study, it was found that emotional status of patients with traumatic SCI and that of their family caregivers was equal [13]. An Iranian study reported that partners score better on physical life domains (e.g., physical functioning and bodily pain), whereas patients were more satisfied on domains such as mental health and general health [14]. In research among stroke patients and their spouses it was found that their levels of life satisfaction were significantly related and that in general patients were less satisfied than spouses [15,16,17,18]. These studies suggest potential reciprocal influences of patient and partner responses of the chronic illness on well-being outcomes. However, it is still largely unclear how mental health and life satisfaction scores of persons with SCI and their partners are related.

The aim of this study is therefore to describe and compare mental health and life satisfaction (overall and in different life satisfaction domains) between individuals with SCI and their partners 5 years after discharge from first inpatient rehabilitation; and to examine if lesion characteristics moderate the association between partners’ and patients’ mental health and life satisfaction.

Methods

Design

Data of the Dutch Umbrella project were used [19], in which individuals with SCI were followed during their rehabilitation up to 5 years after discharge from first inpatient rehabilitation. Recruitment took place between August 2000 and July 2003 in the eight Dutch rehabilitation centres specialised in SCI. At the assessment 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation, we also asked the main informal caregivers of the participants to participate in the study.

Participants

Individuals with SCI were included in the Dutch Umbrella project if they (1) were aged between 18 and 65 years, (2) had a recent onset of SCI and (3) if permanent wheelchair dependency was expected. Exclusion criteria were (1) a progressive disease (e.g., cancer), (2) SCI caused by a malignant tumour, (3) a psychological disorder or (4) insufficient understanding of the Dutch language (last two according to clinical judgement) [19]. In the current study, we used data from couples of individuals with SCI and their main informal caregivers who were also their partner (e.g., not siblings, children or neighbours), and who lived together at the time of the assessment 5 years after discharge.

Procedure

Both individuals with SCI and their partners were asked to complete a self-report questionnaire. Data about the type of SCI was extracted from data earlier collected in the Dutch Umbrella project [19]. A research assistant determined functional independence at time of assessment 5 years after discharge.

Measures

Dependent variables

Mental health was measured with the mental health subscale of the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) [20], which is often used as a screener for mood problems [21]. The total score of the nine items ranges from 0 (poor mental health) up to 100 (very good mental health). Scores of ≤60 indicate low mental health [22]. The SF-36 is formerly used by individuals with SCI and their caregivers [23]. With a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75–0.86 in the present study, the internal consistency of the scale was interpreted as good (≥0.7) [24].

Life satisfaction was measured with the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire (LiSat-9) [25]. The nine items address various domains of life satisfaction: ‘life as a whole’; ‘self-care ability’; ‘leisure situation’; ‘vocational/daily occupation’; ‘financial situation’; ‘sexual life’; ‘partnership relation’; ‘family life’; and ‘contacts with friends’. LiSat-9 item scores range from 1 (very dissatisfying) to 6 (very satisfying). Item scores were dichotomised into ‘dissatisfied’ (score 1–4) and ‘satisfied’ (score 5–6) [26]. The total score is the average of the item scores. Scores of <4.5 were interpreted as ‘low life satisfaction’, scores of ≥4.5 as ‘high life satisfaction’. The LiSat-9 has shown to be a valid measure to assess life satisfaction in individuals with SCI [23] and in partners from stroke survivors [27]. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.77–0.82.

Independent variables

Demographic information included gender, age, participation in paid work (0 versus ≥1 h/week [28]), having children and experienced health with one item from the SF-36, which was dichotomised into ‘good’ (excellent, very good and good) or ‘poor’ (fair and poor).

A research assistant assessed the SCI characteristics [29]. Level of SCI was dichotomised as paraplegia or tetraplegia. Completeness of SCI was dichotomised as motor complete or motor incomplete. Functional independence was measured with Functional Independence Measure motor score (FIM-Motor) [30,31,32]. This scale consists of 13 items and the sum score ranges from 13 to 91. Higher scores indicate higher levels of functional independence. FIM scores were dichotomised in ≤70 or >70 in order to get two groups of more or less equal size. Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was 0.97.

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to describe the study population and outcome variables. Most scores were of ordinal level and therefore non-parametric tests were performed. We computed Spearman’s rho correlations to assess the relationship between total scores of mental health and life satisfaction between individuals with SCI and their partners, in the whole sample and in subgroups based on the level and completeness of SCI and the FIM-score. Significant differences in correlation coefficients were tested using Fisher r-to-z transformation [33]. Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were performed to explore differences in mental health and life satisfaction scores between individuals with SCI and partners. We determined associations between individuals with SCI and partners in dichotomised life satisfaction domains using Cramer’s V values and differences were assessed using McNemar’s tests. We analysed the data with IBM SPSS Statistics 24. A significance level of p < 0.05 (two-tailed) was used. We used Cohen’s standards to interpret the correlations (r = 0.10–0.29, weak; r = 0.30–0.49, moderate; and r ≥ 0.50 strong) [34].

At baseline, 225 individuals with SCI participated in the study and 146 of them completed the follow-up measurement 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Group differences between individuals at baseline and a measurement 1 year after discharge (N = 154) are formerly analysed [35]. In that study was found that participants were less likely to participate 1 year after discharge when the duration of hospitalisation and inpatient rehabilitation was longer, when they had a low level of education and when they had a lower level of life satisfaction at the start of active rehabilitation (which was partly explained by exclusion due to psychiatric problems). We assume that these findings also apply to the measurement used in the current study, since the participants on the measurements one and 5 years after discharge were highly comparable.

Results

Participants

Of the 146 participating individuals with SCI, 80 lived together with a partner, and of them, 69 partners participated the study, which is 70.4% of all participating primary informal caregivers (N = 98). Twenty-nine informal caregivers were no partner (e.g., parent, child or other family) or did not live together at time of the measurement. Four couples of individuals with SCI and their cohabiting partners were excluded because of missing scores on the SF-36 mental health or LiSat-9, resulting in a sample of 65 couples. Table 1 displays characteristics of the individuals with SCI and their partners.

Mental health and life satisfaction

Persons with SCI and their partners had the same median mental health scores of 76.0 and their mental health scores were moderately and positively correlated (Table 2). It was found that 26.1% of the partners and 13.8% of the individuals with SCI had low mental health.

Life satisfaction scores of individuals with SCI (median (Mdn) = 4.8, interquartile range (IQR) = 4.2-5.0) and their partners (Mdn = 4.6, IQR = 4.0–5.1) were not significantly different from each other and were positively correlated. It was found that 47.7% of the partners and 32.3% of the individuals had low life satisfaction.

Table 3 shows that the correlations between mental health and life satisfaction of patients and partners were different between the subgroups based on SCI characteristics. Mental health scores of individuals with paraplegia and their partners were strongly and significantly related, but this was not found among individuals with a tetraplegia and their partners. The correlation between life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and their partners was stronger in the subgroup with a >70 FIM-score (compared with a score of ≤70).

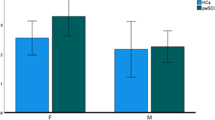

Table 4 shows the associations between life satisfaction scores of individuals with SCI and their partners in separate life satisfaction domains. Moderate positive and significant correlations were found with respect to the domains ‘life as a whole’, ‘financial situation’, ‘sexual life’, ‘partnership relation’ and ‘family life’. No associations were found in the other domains. Furthermore, Fig. 1 shows many differences in (dis)satisfaction between partner and individual with SCI per life satisfaction domain. McNemar’s test demonstrated that compared with their partners, individuals with SCI were more satisfied with their ‘leisure situation’ (patients satisfied 68.8% and partners 51.6%), ‘partnership relation’ (patients satisfied 90.3% and partners 67.7%) and ‘family life’ (patients satisfied 90.6% and partners 68.8%), and less satisfied with their ‘self-care ability’ (patients satisfied 50.8% and partners 85.2%). Overall, individuals with SCI and their partners were most often dissatisfied with their ‘sexual life’.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the differences and associations in mental health and life satisfaction scores of persons with SCI and their partners 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation. Median total mental health and life satisfaction scores of individuals with SCI and their partners were similar and moderately to strongly related to each other. However, the differences found on individual life domains also indicate that there may be considerable differences in appreciation between partners in a relationship.

This study has several strengths. First, this is one of the first studies to gather data of both partners and individuals with SCI and provides insight into the impact of SCI on families instead of on different persons independently. Second, data were collected at a uniform point of time (5 years after discharge from first inpatient rehabilitation). In former studies, large variations in duration since SCI may have had impact on the results.

Mental health and life satisfaction: levels

Median mental health and life satisfaction levels found in our study were comparable to those of the generic Dutch country population [22, 36]. In our study, 13.8% of the individuals with SCI and 26.1% of the partners reported low mental health. In the Dutch adult population, 13.7% reported low mental health, with females reporting low mental health more often than males (respectively, 16.7% and 10.5%) [37]. In our study, most individuals with SCI were male (67.7%) and most partners were female (64.6%), which may partly explain the difference in mental health between individuals with SCI and their partners. However, considering this gender difference, the percentage of partners who report low mental health is still relatively high. In our study, 32.3% of the individuals with SCI and 47.7% of the partners report low overall life satisfaction. To compare, in the Dutch population 34% report low life satisfaction [36]. Again, gender differences may partly explain the difference.

Mental health and life satisfaction: relationship and comparison

In the literature, no studies on the relationships between mental health scores of individuals with SCI and their partners were found. Studies in other diagnostic groups showed similar results to our study findings [38, 39].

The association we found between life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and partners is consistent with previous findings found in research conducted with caregiver–patient dyads in other chronic illness groups [15]. Studies among individuals with stroke and their partners found that partners reported lower levels of life satisfaction [15, 18] and higher anxiety compared to individuals with stroke [16]. However, and in accordance with our study, no differences in emotional status levels between SCI patients and their partners were found [13].

Focusing on separate life domains, differences in life satisfaction between individuals with SCI and their partners were found. No association was found in domains, which are not automatically shared by patients and partners (‘self-care ability’, ‘leisure situation’, ‘vocational/daily occupation’ and ‘contacts with friends’). Moderate positive significant associations were found in more mutual life satisfaction domains (‘financial situation’, ‘sexual life’, ‘partnership relation’ and ‘family life’).

Individuals with SCI and their partners were both least satisfied with their ‘sexual life’, which is in accordance with earlier research [15, 18, 40]. It is likely that the SCI and related physical (e.g., bladder and/or bowel incontinence) [2] and mental (e.g., impaired body image) [41] problems influence their sexual relationship [42].

We found that patients were significantly more often satisfied on the domains of ‘leisure situation’, ‘partnership relation’ and ‘family life’; and partners significantly more often on the ‘self-care ability’ domain. This partly corresponds with the results of a former study among SCI patients and their partners in which was found that patients were more satisfied on mental domains and partners on physical domains [14, 43]. Comparable results were also found in studies about life satisfaction among couples of stroke patients and their partners 1 and 3 years after stroke. In those studies was found that patients scored higher on the domain of partnership relation and lower on the ‘self-care ability’ domain (only significant 1 year after stroke) [15, 18]. Higher satisfaction among the partners on the physical ‘self-care ability’ domain is not surprising because all patients with SCI experience a certain degree of physical impairment within their daily activities [1, 2]. That partners were less satisfied than patients on the ‘leisure time’ domain corresponds with findings in caregiver studies in different diagnostic groups where it was found that more leisure time was one of the main needs of caregivers (of who most were partner) [44,45,46]. Finally, lower satisfaction among partners in the ‘partnership relation’ and ‘family life’ domains may be explained by a change in role from spouse and lover to care provider and the new assumed responsibilities. Individuals with SCI are dependent and need support, partners provide support. In former research it was found that different stressors are negatively associated with caregiving and the evaluation of life satisfaction, like the changed relationship, anger or resentment towards partner with SCI, feeling trapped, loss of intimacy, lack of appreciation or respect from partner with SCI, and stress of multiple roles [9, 47].

We also, although not consistently, found that relationships between mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and partners appear to be stronger in individuals with a paraplegia and higher functional independence. This may just be a coincidence, but it may also reflect diminishing cohesion within the couple following a severe disability of one of the partners over time [9, 48].

Limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, this study concerned a selected group of individuals with SCI, since only wheelchair-dependent individuals with SCI were included. Therefore, results are only representative for this selected group. However, the selection resulted in a homogenous group of individuals with a more severe SCI, which is interesting since this group is highly dependent on rehabilitation care. Second, partners only participated in the measurement 5 years after discharge. Therefore, it is not possible to compare mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and their partners earlier after SCI onset in order to conclude anything about the course of mental health and life satisfaction. Third, attrition bias must be taken into account when interpreting the results. In particular the finding that follow-up participants had higher life satisfaction may lead to an overestimation of the life satisfaction by individuals with SCI 5 years after discharge.

Implications

The current main focus in clinical practice for the individual with SCI is on physical consequences. This study adds to the evidence suggesting that it is recommended to pay more attention to partners perceived life satisfaction and mental health in order to promote their well-being, and it adds to this evidence that clinicians cannot assume that the partner’s experienced life satisfaction is in line with the individual with SCI’s life satisfaction. A focus on changing family roles, personal needs and responsibilities early in the rehabilitation process could possibly contribute to their life satisfaction, whereas it was found that partners were less satisfied in the life satisfaction domains ‘partnership relation’, ‘family life’ and ‘leisure time’. Especially, the finding that partners were less satisfied with their partnership relation than the individual with SCI needs attention. Former research showed that partners who rate their partnership relation as low encounter more subjective caregiver burden and less caregiver satisfaction, which is a risk for burnout [49].

Special attention also is needed for the domain of ‘sexual life’, whereas it was found that in 81.7% of all couples at least one person was dissatisfied. Our findings are in accordance with previous findings that people with more severe physical impairments report low sexual satisfaction [50] and that injury-related changes could function as barriers to intimacy (for partner and patient) [51]. Furthermore, former studies found that individuals with SCI were less satisfied with their sexual life compared with a general population group [36] and compared with their own situation before SCI [40]. All these findings emphasise the importance for more attention on sexual functioning and abilities in rehabilitation care [52].

In rehabilitation care, attention for the caregiver and awareness of the importance of family-centred care is growing. However, overall more research on the specific needs of individuals with SCI and their partners/caregivers is needed in order to come to concrete recommendations for rehabilitation care. Qualitative research, like interviews, could be valuable in the exploration of personal needs of individuals with SCI and their partners and the individual differences in needs that do exist. Quantitative cohort and longitudinal research could contribute to a more general insight in needs and the changes in needs overtime. More insight in needs could be beneficial in the development of interventions aimed to promote mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with SCI and their partners. Existing interventions, which focus on patients and their caregivers, like family conferences, are promising, however, there is still limited empirical evidence particular in the area of rehabilitation [53, 54]. Future research is needed for the development, implementation and evaluation of such interventions, which are aimed to sufficiently equip families to cope with the effects of an SCI on their personal lives.

Conclusion

On average, individuals with SCI and their partners showed equal mental health and life satisfaction, and their total scores on these measures were positively related to each other. However, these associations were only moderate, thereby suggesting considerable differences between individuals with SCI and their partners. Discrepancies between individuals with SCI and their partners were found with respect to various life domains. Therefore, the focus of attention on mental health and life satisfaction (domains) should be different for individuals with SCI and partners in clinical practice and in future research.

References

Bloemen-Vrencken JHA, Post MWM, Hendriks JMS, De Reus ECE, De Witte LP. Health problems of persons with spinal cord injury living in the Netherlands. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:1381–99.

Adriaansen JJE, Post MWM, De Groot S, Van Asbeck FWA, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, Tepper M, et al. Secondary health conditions in persons with spinal cord injury: a longitudinal study from one to five years post-discharge. J Rehabil Med. 2013;45:1016–22.

Post MWM, Van Leeuwen CMC. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord. 2012;50:382–9.

Barclay L, McDonald R, Lentin P. Social and community participation following spinal cord injury: a critical review. Int J Rehabil Res. 2015;38:1–19.

Williams R, Murray A. Prevalence of depression after spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96:133–40.

Le J, Dorstyn D. Anxiety prevalence following spinal cord injury: a meta-analysis. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:570–8.

Visser-Meily A, Post M, Gorter JW, Van Berlekom SB, Van Den Bos T, Lindeman E. Rehabilitation of stroke patients needs a family-centred approach. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28:1557–61.

Boschen KA, Tonack M, Gargaro J. The impact of being a support provider to a person living in the community with a spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol. 2005;50:397–407.

Charlifue SB, Botticello A, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, Richards JS, Tulsky DS. Family caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury: exploring the stresses and benefits. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:732–6.

Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. J Am Med Assoc. 2014;311:1052–9.

Middleton JW, Simpson GK, De Wolf A, Quirk R, Descallar J, Cameron ID. Psychological distress, quality of life, and burden in caregivers during community reintegration after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1312–9.

Chan R. Stress and coping in spouses of persons with spinal cord injuries. Clin Rehabil. 2000;14:137–44.

Paker N, Bugdayci D, Dere D, Altuncu Y. Comparison of the coping strategies, anxiety, and depression in a group of Turkish spinal cord injured patients and their family caregivers in a rehabilitation center. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2011;47:595–600.

Ebrahimzadeh MH, Golhasani Keshtan F, Shojaee BS. Correlation between health-related quality of life in veterans with chronic spinal cord injury and their caregiving spouses. Arch Trauma Res. 2014;3:e16720.

Achten D, Visser-Meily JMA, Post MWM, Schepers VPM. Life satisfaction of couples 3 years after stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1468–72.

Dankner R, Bachner YG, Ginsberg G, Ziv A, Ben David H, Litmanovitch-Goldstein D, et al. Correlates of well-being among caregivers of long-term community-dwelling stroke survivors. Int J Rehabil Res. 2016;39:326–30.

Eriksson G, Tham K, Fugl-Meyer AR. Couples’ happiness and its relationship to functioning in everyday life after brain injury. Scand J Occup Ther. 2005;12:40–48.

Carlsson GE, Forsberg-Wärleby G, Möller A, Blomstrand C. Comparison of life satisfaction within couples one year after a partner’s stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39:219–24.

De Groot S, Dallmeijer A, Post M, Van Asbeck F, Nene A, Angenot E, et al. Demographics of the Dutch multicenter prospective cohort study ‘Restoration of mobility in spinal cord injury rehabilitation’. Spinal Cord. 2006;44:668–75.

Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36). Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

Ku JH. Health-related quality of life in patients with spinal cord injury: review of the short form 36-health questionnaire survey. Yonsei Med J. 2007;48:360–70.

Van Leeuwen CM, Hoekstra T, Van Koppenhagen CF, De Groot S, Post MW. Trajectories and predictors of the course of mental health after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:2170–6.

Post MWM, Van Leeuwen CM, Van Koppenhagen CF, De Groot S, Dijkers MP. Validity of the Life Satisfaction Questions, the Life Satisfaction Questionnaire, and the Satisfaction With Life Scale in persons with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93:1832–7.

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–55.

Fugl-Meyer AR, Branholm I-B, Fugl-Meyer KS. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clin Rehabil. 1991;5:25–33.

Visser-Meily A, Post M, Van de Port I, Van Heugten C, Van, den Bos T. Psychosocial functioning of spouses in the chronic phase after stroke: Improvement or deterioration between 1 and 3 years after stroke? Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:153–8.

Kruithof WJ, Visser-Meily JMA, Post MWM. Positive caregiving experiences are associated with life satisfaction in spouses of stroke survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;21:801–7.

Statistics Netherlands (CBS). Statistics Netherlands opts for international definitions of unemployment and inflation. 2014. https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2014/27/statistics-netherlands-opts-for-international-definitions-of-unemployment-and-inflation. Accessed 21 June 2017.

Maynard FM, Bracken MB, Creasey G, Ditunno JF, Donovan WH, Ducker TB, et al. International standards for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 1997;35:266–74.

Hall KM, Cohen ME, Wright J, Call M, Werner P. Characteristics of the Functional Independence Measure in traumatic spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80:1471–6.

Post MWM, Dallmeijer AJ, Angenot ELD, Van Asbeck FWA, Van der Woude LHVV, Duration and functional outcome of spinal cord injury rehabilitation in the Netherlands. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005;42:75–85.

Kidd D, Stewart G, Baldry J, Johnson J, Rossiter D, Petruckevitch A, et al. The Functional Independence Measure: a comparative validity and reliability study. Disabil Rehabil. 1995;17:10–14.

Siegel S. Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1956.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Academic Press; 1988.

De Groot S, Haisma JA, Post MWM, Van Asbeck FWA, Van der Woude LHV. Investigation of bias due to loss of participants in a Dutch multicentre prospective spinal cord injury cohort study. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:382–9.

Post MWM, Dijk AJVan, Asbeck FWAVan, Schrijvers AJP, Van Dijk AJ, Van Asbeck FWA, et al. Life satisfaction of persons with spinal cord injury compared to a population group. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1998;30:23–30.

Driessen M. Geestelijke ongezondheid in Nederland in kaart gebracht [Mental helalth in the Netherlands]. The Hague (the Netherlands). 2011. http://www.cbs.nl/NR/rdonlyres/EF66D80A-C019-4EF0-8D13-4A54999C37EE/0/2011geestelijkeongezondheidinNederlandinkaartgebrachtart.pdf. Accessed at 22 June 2017.

Kershaw T, Ellis KR, Yoon H, Schafenacker A, Katapodi M, Northouse L. The interdependence of advanced cancer patients’ and their family caregivers’ mental health, physical health, and self- efficacy over time. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49:901–11.

Kühl K, Schürmann W, Rief W. Mental disorders and quality of life in COPD patients and their spouses. Int J COPD. 2008;3:727–36.

Van Koppenhagen CF, Post MW, Van der Woude LH, De Witte LP, Van Asbeck FW, De Groot S, et al. Changes and determinants of life satisfaction after spinal cord injury: a cohort study in The Netherlands. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89:1733–40.

Van Diemen T, Van Leeuwen C, Van Nes I, Geertzen J, Post M. Body image in patients with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:1126–31.

Anderson KD, Borisoff JF, Johnson RD, Stiens SA, Elliott SL. The impact of spinal cord injury on sexual function: concerns of the general population. Spinal Cord. 2007;45:328–37.

Ebrahimzadeh MH, Shojaei B-S, Golhasani-Keshtan F, Soltani-Moghaddas SH, Fattahi AS, Azloumi SM, Quality of life and the related factors in spouses of veterans with chronic spinal cord injury. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:48.

Cameron JI, Naglie G, Silver FL, Gignac MAM. Stroke family caregivers’ support needs change across the care continuum: a qualitative study using the timing it right framework. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:315–24.

Sklenarova H, Krümpelmann A, Haun MW, Friederich H-C, Huber J, Thomas M, et al. When do we need to care about the caregiver? Supportive care needs, anxiety, and depression among informal caregivers of patients with cancer and cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121:1513–9.

De Wit J, Schröder C, El Mecky J, Beelen A, Van den Berg L, Visser-Meily J. Support needs of caregivers of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. In press.

Dickson A, O’Brien G, Ward R, Allan D, O’Carroll R. The impact of assuming the primary caregiver role following traumatic spinal cord injury: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the spouse’s experience. Psychol Health. 2010;25:1101–20.

Visser-Meily A, Post M, Van de Port I, Maas C, Forstberg-Wärleby G, Lindeman E. Psychosocial functioning of spouses of patients with stroke from initial inpatient rehabilitation to 3 years post stroke: Course and relations with coping strategies. Stroke. 2009;40:1399–404.

Tough H, Brinkhof MW, Siegrist J, Fekete C. Subjective caregiver burden and caregiver satisfaction: The role of partner relationship quality and reciprocity. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;98:2042–51.

McCabe MP, Taleporos G. Sexual esteem, sexual satisfaction, and sexual behavior among people with physical disability. Arch Sex Behav. 2003;32:359–69.

Gill CJ, Sander AM, Robins N, Mazzei DK, Struchen MA. Exploring experiences of intimacy from the viewpoint of individuals with traumatic brain injury and their partners. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2011;26:56–68.

Simpson La, Eng JJ, Hsieh JTC, Wolfe DL, Program GC. The health and life priorities of individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. J Neurotrauma. 2013;29:1548–55.

Fronek P. The RAP in rehabilitation: the family conference in practice. SCI Psychosoc Process. 2008;21:26–36.

Witteveen E. Mantelzorg en netwerkondersteuning bij hersenletsel [Informal care and network support in brain injury]. Utrecht, 2012 http://www.cursussen.hu.nl/~/media/sharepoint/Lectoraat Participatie Zorg en Ondersteuning/2012/witteveen 2012 Eindrapportage onderzoek Mantelzorgondersteuning Oktober 2012 1.pdf. Accessed 21 Apr 2015.

Funding

The Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development funded the 5-year follow-up of the Umbrella project, grant number 14350003.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

We certify that we followed all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers during the course of this research. The Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht approved this study.

Informed consent

Informed consent of the individuals with spinal cord injury was obtained at inclusion in the cohort. Partner’s informed consent was obtained at the measurement 5 years after discharge from inpatient rehabilitation (their first moment of participation).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scholten, E., Tromp, M., Hillebregt, C. et al. Mental health and life satisfaction of individuals with spinal cord injury and their partners 5 years after discharge from first inpatient rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 56, 598–606 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0053-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-017-0053-z

This article is cited by

-

Environmental and systems experiences of persons with spinal cord injury and their caregivers when transitioning from acute care to community living during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparative case study

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2023)

-

Caregiver burden according to ageing and type of care activity in caregivers of individuals with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord Series and Cases (2023)

-

Positive sexuality in men with spinal cord injury

Spinal Cord (2018)