Abstract

The identification of amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) pathogenic mutations in familial early onset Alzheimer’s disease (AD), along with knowledge that amyloid-β (Aβ) was the principle protein component of senile plaques, led to the establishment of the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Down syndrome substantiated the hypothesis, given an extra copy of the APP gene and invariable AD pathology hallmarks that occur by middle age. An abundance of support for the amyloid cascade hypothesis followed. Prion-like protein misfolding and non-Mendelian transmission of neurotoxicity are among recent areas of investigation. Aβ-targeted clinical trials have been disappointing, with negative results attributed to inadequacies in patient selection, challenges in pharmacology, and incomplete knowledge of the most appropriate target. There is evidence, however, that proof of concept has been achieved, i.e., clearance of Aβ during life, but with no significant changes in cognitive trajectory in AD. Whether the time, effort, and expense of Aβ-targeted therapy will prove valuable will be determined over time, as Aβ-centered clinical trials continue to dominate therapeutic strategies. It seems reasonable to hypothesize that the amyloid cascade is intimately involved in AD, in parallel with disease pathogenesis, but that removal of toxic Aβ is insufficient for an effective disease modification.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Amyloid-β cascade hypothesis

Genetic evidence

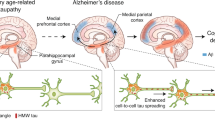

The linkage of pathological lesions to amyloid-β (Aβ) along with discoveries in genotype–phenotype relationships led to the amyloid cascade hypothesis [1] (Fig. 1). The hypothesis held then, as it does now, that Aβ is causative of the neurodegenerative processes in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Genetic evidence was apparent in Down syndrome patients, who constitutively overexpress Amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) gene and consequently develop hallmark lesions of AD early in life [2]. Mutations in the carboxy-terminal portion of APP causing hereditary AD or cerebral hemorrhage were also cited and continue to be compelling evidence in favor of the amyloid cascade [3, 4].

Amyloid-β cascade hypothesis. Amyloid-β precursor protein (APP) gene expression is followed by consecutive protease processing by β-secretase 1 (BACE1) and γ-secretase complex (PSEN1 (presenilin 1), PSEN2 (presenilin 2), nicastrin and APH1 (anterior pharynx-defective 1)) releasing the amyloid-β peptide, including pathogenic species Aβ42. Aβ42 undergoes conformational change, assembles into oligomers (2–100 units) and protofibrils (>100 kDa), which are neurotoxic, and ultimately deposits as senile plaques

Since the original hypothesis, a large body of supporting literature has accumulated. A number of additional APP mutations causing familial AD (FAD) have been described, the majority occurring within or near the transmembrane region of AβPP. Pathogenic mutations in presenilin 1 and 2 genes (PSEN1, PSEN2) also cause familial AD, with PSEN1 mutations being the most common among dominantly inherited FAD kindreds. Presenilin proteins are the catalytic subunits of the gamma-secretase complex required along with beta secretase 1 (BACE1) for Aβ peptide processing and secretion [5]. Sequential C-terminal Aβ cleavage by gamma secretase generates Aβ fragments of differing lengths, with 40 amino acid (Aβ40) and 42 amino acid (Aβ42) being the most common. An increased Aβ42:Aβ40 ratio is described in plasma and cultured fibroblasts from familial AD patients [6, 7], suggesting Aβ42 as the pathogenic Aβ species [8]. The predominance of Aβ42 in affected areas of the AD brain tissue lacking cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) supports this claim [9], although data in sporadic AD are sparse and somewhat contradictory [6]. The tendency for Aβ42 to spontaneously self-assemble into fibrils is thought to underlie its pathogenicity [10]. It is generally accepted that Aβ40 is relatively more abundant in cerebral amyloid angiopathy [8], although Aβ42 may “seed” blood vessels initially and may be present to a variable extent [9, 11, 12]. Interestingly, Aβ40 may inhibit fibrillar aggregation [13, 14], which is more in line with a bystander role for Aβ40 in CAA.

Apolipoprotein E

Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) is the glycoprotein product of the polymorphic APOE gene on chromosome 19 [15], first described in 1973 as a component of very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) [16]. Initial interest in ApoE was centered on its role in cholesterol-induced hyperlipidemia, as its primary role is the transport and delivery of cholesterol and other lipids in the plasma and central nervous system. The potential role of ApoE in AD and amyloidogenesis was discovered serendipitously in the early 1990’s with Affected Pedigree Analysis linking familial clusters of late-onset AD to the long arm of chromosome 19 [17]. Independent experiments by Strittmatter et al. showed variable binding of ApoE, one of a number of candidate proteins transcribed in the region of 19q identified by linkage analysis, to Aβ as a function of APOE polymorphism [18]. The three major allelotypes (e2, e3, and e4) differ at positions 112 and 158, which affects ApoE conformation, receptor binding affinity, and stability [19,20,21,22].

Importantly, ApoE e4 allele is the most significant genetic risk factor for AD identified to date, and has a gene dosage effect in terms of disease risk, age at onset, and Aβ neuropathology [23,24,25,26]. In line with the amyloid cascade hypothesis, ApoE binds Aβ in an isoform-specific manner, with e4 showing the lowest binding affinity [27], consistent with other data indicating its role in Aβ clearance [28]. ApoE has also been shown to stabilize Aβ oligomers [29]. The association between ApoE genotype and AD appears to be stronger in women [30, 31], less robust for African-Americans and Hispanics [32], and appears to diminish somewhat with advanced age. ApoE4 is nevertheless heavily enriched in AD patients, with 65–80% of AD patients carrying at least one Apo e4 allele [33], compared to worldwide frequency of about 14%. E2 is said to be “protective” as noted above, reducing the AD risk by about half [34, 35], possibly related to greater protein stability [36].

Aβ oligomers

The lack of eloquence with respect to fibrillary Aβ deposits and neurological signs indicates a level of complexity to AD pathogenesis, unaccounted for by hallmark lesions [37]. Accordingly, the revised amyloid cascade hypothesis tends to minimize insoluble Aβ as the neurotoxic species, in favor of low-n assembly fibrillar intermediates [38, 39], while senile plaques deposit either en passant, or as an anatomically imprecise reservoir in dynamic equilibrium with toxic soluble Aβ oligomers [6, 40]. Interestingly, beta sheet content tends to increase as a function of oligomer size, while neurotoxicity of dimers, trimers, and tetramers is 3-fold, 8-fold, and 13-fold higher, respectively in comparison with Aβ monomers [41].

Oligomers of Aβ42 are neurotoxic to synapses and impair memory in rats, whereas senile plaque cores do not impair long-term potentiation [42]. The concept of a toxic penumbra of Aβ42 oligomers has been raised, consistent with data in APP/PS1 transgenic mice suggesting a halo of decreasing synapse loss for a distance of 50 μm from Aβ senile plaques [43]. Aβ oligomers have been shown to correlate with disease severity [44]. Human AD brains versus non-AD controls with comparable Aβ burden examined by oligomer specific ELISA showed higher oligomer to senile plaque ratios in AD patients [45]. This suggests a qualitative difference in AD versus plaque-rich controls that might explain substantial senile plaque burden with apparently intact cognition. Remarkably, Aβ oligomer levels distinguished demented from non-demented patients in all cases studied, consistent with the concept that a physical limit is reached in AD at which point Aβ oligomers would perhaps diffuse onto synaptic membranes or other hydrophobic surfaces initiating neurodegeneration [46]. Aβ Oligomers have been implicated in an extensive array of molecular outcomes [47]. Preliminary attempts to identify oligomeric forms in vivo as potential AD biomarkers, including quantification by ELISAs, flow cytometry, misfolded protein assays, and surface fluorescence distribution analysis, have been encouraging [47], in agreement with the role of Aβ oligomers in disease.

The complexity of oligomer biology, however, is substantial (reviewed in [48]). Nosology alone is unwieldy. Aβ Oligomers may be separated by number of mononers, e.g., dimer, trimer, tetramer, 12-mer, 32-mer etc. There may be differences in three-dimensional structure and arrangement, such as “globulomers,” annular protofibrils, or linear protofibrils. There may be a mixture of Aβ oligomeric species with overlapping properties in dynamic equilibrium. Sample preparation using detergents can induce oligomerization artifacts. Aβ species may vary by concentration, temperature, pH, salt, metal ions, and other chemical variables. Toxicity assays vary widely, with no standards for inter-laboratory comparison. Toxicity may be measured by acute changes in morphology of dendritic spines, apoptosis, ex vivo hippocampal electrophysiology, neurotransmission in cell culture, or neurobehavioral changes in rodents, which imperfectly model AD biology. The collective literature further provides no clarity in terms of which of the bewildering array of Aβ oligomer species are more or less relevant to trigger neurotoxicity, but implies instead the existence of a soluble “Aβ soup” [48] as an amorphous explanation to complex biology.

Aβ prions

Differences in conformation of neurotoxic proteins and the possibility of protein-mediated, non-Mendelian transmission of phenotypic information raises the issue of the “Aβ prion”. Both Aβ and pathological prion protein (PrPsc) share protease resistance [49]. Both Aβ and PrPsc may be capable of conformational templating, or “seeding.” [50] Aβ may undergo misfolding into distinct conformers or “strains,” both in vitro and in vivo [51]. Aβ seeds inoculated into brain show features of Aβ aggregation, and neuroanatomical propagation [52]. Increased Aβ deposition is described in subjects with and without iatrogenic CJD (Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease) [53]. Both Aβ and PrPsc may cause a secondary tauopathy [54]. Perhaps most compelling is the study by Cohen et al. [10], in which a distinct, rapidly progressive AD phenotype was associated with distinctly structured Aβ42 species (30–100 monomers) [55]. This parallels sporadic CJD subtypes with distinct differences in disease progression and pathologic phenotype on the basis of PRNP codon 129 polymorphism and the size of the PrPsc conformer [56], i.e. strain. This study also confirms the pathogenic relevance of Aβ42 over Aβ40, in that Aβ40 remained largely as soluble monomers with no features suggesting strain variation with phenotype.

The analogy of Aβ to PrPsc is lessened somewhat by the fact that PrPsc and CJD pathology do not appear in asymptomatic patients. PrPsc is indicative of clinical disease and its absence is indicative of absence of clinical disease [57]. Horizontal transmission of Aβ proteinopathy, either iatrogenically in humans, or by serial passage of distinct Aβ conformers associated with distinct phenotypes in experimental animals, is not described. Establishing standardized procedures for laboratory determination of prion-like transmission is another challenge. It remains to be seen whether the “Aβ prion” will translate into a viable target for AD therapy.

Targeting Aβ for disease modification

It is clear from the above discussion that identifying a specific Aβ species (monomer, dimer, oligomer, fibrillar, senile plaques, etc.) as a target for therapy is a formidable challenge. The numerous oligomeric species may be more or less relevant, transient, and immunogenic [48]. The potential conformations and antigenicity of the spectrum of potential oligomers may be impossible to define by current methodology. Pathogenic relevance of a given species may vary depending on diverse factors such as ApoE genotype [10], race [58], genetic factors not fully characterized [59], or other co-factors not yet characterized. A given Aβ species may relate to selective vulnerability (classic AD, versus limbic predominant AD or hippocampal sparing AD [60]), or other endophenotypes such as rapid disease progression. To this is added the complexities of immunology [61], blood brain barrier penetration, dosing, and cerebral and systemic toxicity. In the event of successful target engagement (which is not demonstrated in most trials to date [62]), human factors such as clinical trial attrition rates [61] and diagnostic inaccuracy [63] may degrade statistical assessment.

Proposals for disease-modifying therapy require targeting of AD biology [64]. Ancillary features of AD biology, such as neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, provide myriad additional targets to neurotoxic Aβ, but these tend to be viewed as significant only insofar as they represent effector processes from downstream of the Aβ cascade [63]. Despite the challenges and repeated failures in clinical trials, Aβ remains the primary target for disease-modifying therapies (Fig. 2). Attempts at species-specific targeting is on-going (Fig. 3). Specific linear Aβ domains (e.g. N-terminal, C-terminal, mid domain) have been used to generate antibodies [65]. These may target monomers and fibrillar Aβ species, since the N-terminal domain remains exposed to the external or cellular environment in fibrillar Aβ arrangements [61] while the C-terminal is not. Antibodies may target protofibrils (>100 kDa) specifically [66], or other oligomerization states for unclear reasons [67]. The IVIg construct theoretically targets oligomers and fibrils, since the 0.5% of antibodies that bind Aβ exhibit very little monomeric Aβ binding [68]. Constructs that target protease cleavage rely on the premise of Aβ overproduction as the driver of disease, or modulation of the Aβ cleavage, rather than clearance of Aβ species (Fig. 4). Numerous other approaches and epitope specificities will likely be added as time goes on. Table 1 lists amyloid-targeted therapeutic intervention attempts completed or in progress, indicating the agent, and putative target/mechanism, although it is apparent that targets may be presumed more than actually targeted in any given construct because of inherent complexities.

Distribution by molecular target of amyloid-related clinical trials. Diagram shows selected amyloid-related clinical trials of compounds divided into their molecular target. For Immunotherapies, compounds were subclassified into vaccines and therapeutic antibodies. Small drugs were classified into compounds that interfere with Aβ aggregation, modulators of β-secretase, γ-secretase or α-secretase, or compounds with overall effects on neuronal/brain metabolism

Schematic of Amyloid-β therapeutic strategies. Diagram shows selected Aβ related compounds divided into immunotherapies that target N- or C-terminus or epitopes present in high-order oligomers of fibrillar assemblies. Additional compounds intended as Aβ-vaccines or to interfere with Aβ-aggregation into fibrillar aggregates. Compounds in red text are inactive/discontinued in clinical trials. Despite the diversity of Aβ species targeted, clinical trials to date have failed to demonstrate disease modification. Atomic structures from PDB 5OQV and EMB-3851, were modeled with PyMOL and UCSF Chimera

Schematic of Secretase therapeutic approaches. Modulators of β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase complex. BACE1 structure from PBD 6EJ2, yellow area indicates the catalytic site where most of the compounds exert effects as modulators or inhibitors. γ-secretase complex structure from PDB 5A63, yellow area indicated the PSEN1 domain and red area the PSEN2 domain. Compounds in red text indicate that they are inactive/discontinued. Secretase inhibition has been disappointing to date, in some cases performing worse than placebo, with increased adverse reactions (e.g Semagacestat). Atomic were structures modeled with PyMOL and UCSF Chimera

Selected Aβ targeted constructs in phase 3 clinical trials

Bapineuzumab

Bapineuzumab or AAB-001 is a humanized IgG1 version of the mouse monoclonal antibody 3D6 that binds the N-terminus of Aβ, an exposed epitope in fibrillary Aβ deposits. Following an unpublished phase 1 study showing potential treatment benefit, the initial phase II study included primary outcomes that trended toward improved cognitive scores but with emerging neurovascular complications, prompting post hoc analyses [69].

A meta-analysis of six phase 3 randomized clinical trials (n = 2380) showed no differences from placebo among four doses (0.15, 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/kg), except for the 0.15 mg/kg dose, which showed significant worsening on the ADAS-cog11 scale [70]. A second phase 3 trial that excluded ApoE e4 carriers because of neurovascular complications also showed no clear benefits [61]. Biomarker analysis suggested exposure-dependent reductions in brain amyloid burden [71]. Studies differ on whether Bapineuzumab was associated with increased ventricular volume by magnetic resonance imaging [71, 72]. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with vagogenic edema (ARIA-E) increased with increasing dose in non-APOE e4 carriers, and was significantly increased in APOE e4 carriers compared to non-carriers [73]. ARIA-E occurred despite the attempts to reduce this complication by lowering the dose [74]. Treatment was also complicated by amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with microhemorrhage (ARIA-H).

Solanezumab

Solanezumab or LY2062430 is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that recognizes the mid region of Aβ. It is derived from mouse monoclonal antibody m266 that recognizes the Aβ16-24 epitope [62]. It is thought to bind monomeric, soluble Aβ rather than fibrillar or senile plaque Aβ [75], with only 0.1% blood brain barrier penetration [61]. Two phase 3, double-blind trials involving a total of 2052 patients with mild-to-moderate AD received 400 mg intravenous solanezumab or placebo every 4 weeks for 18 months [76]. Primary outcomes were Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS-cog) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living Scale (AADCS-ADL). Neither clinical trial showed significant improvement in primary outcome measures, notwithstanding nonsignificant trends in subjects with mild AD [61]. In contrast to Bapineuzumab, there was no difference between treatment and placebo groups with respect ARIA-E or ARIA-H. This may be attributed to a lack of fibrillar Aβ binding.

Noteworthy with respect to targeted soluble versus insoluble Aβ was a study examining experimental administration of 3D6 (mouse version of Bapineuzumab) [77]. In this study, an increased frequency of microhemorrhages in experimental mice was noted in the absence of plaque removal. These data were at odds with the notion that clearing of cerebral amyloid angiopathy co-segregates with clearing of plaque. The investigators concluded that antibodies binding to soluble and insoluble Aβ lack therapeutic plaque lowering, and that soluble Aβ blocked target engagement in existing plaque. Whether plaque lowering is truly therapeutic remains an open question [78].

Intravenous Immunoglobulin G

Intravenous Immunoglobulin G (IVIg) is polyclonal IgGs pooled from healthy donors. The rationale for a potential Aβ-targeted therapy is based on the findings that anti-Aβ antibodies in the blood and CSF are reduced in AD compared to controls [79] and that commercial preparations of IVIg contain natural anti-Aβ antibodies [80]. About 0.5% of all antibodies in IVIg bind with Aβ. Similarly, a retrospective national database analysis demonstrated a risk reduction in the diagnosis of AD following IVIg administration [81]. The precise target of anti-Aβ antibodies in IVIg preparations is unclear, however. IVIg has been shown to inhibit fibril formation [82], Aβ-mediated toxicity [83], and Aβ aggregation [84], and enhance Aβ clearance [85]. IVIg administered to APP/PS1 transgenic mice suggested binding within the brain but not of senile plaques [84].

In a phase 3, double-blinded trial [86], 390 subjects with mild to moderate AD were randomly administered IVIg (0.2 or 0.4 g/kg every 2 weeks for 18 months) or placebo. Outcome measures included ADAS-cog11 and ADCS-ADL. Significant decreases in Aβ42 were observed with IVIg treatment, but with no differences in ARIA-E or ARIA-H. No beneficial effects on cognition outcomes was demonstrated.

Tramiprosate

Tramiprosate (known as Alzhemed, Vivimind or NC-531) is a glycosaminoglycan mimetic thought to prevent Aβ aggregation via soluble Aβ binding [62]. In a mass spectrometry study, a 10-fold molar excess of tramiprosate led to 50% binding of Aβ40 and Aβ42 [87], although the high concentrations of both substances required to demonstrate binding, and lack of activity in the aqueous phase raise questions about the actual in vivo anti-aggregation properties of this compound [62]. Overall, other than the general concept that tramiprosate is thought to prevent Aβ amyloidosis, the precise Aβ species targeted by tramiprosate is unclear.

In a phase 3, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 67 medical centers in the United States and Canada, 1052 subjects with mild to moderate AD were randomly assigned tramiprosate (100 mg and 150 mg BID) and placebo [88]. Primary outcomes included ADAS-cog and Clinical Dementia Rating—Sum of Boxes (CDR-SB). No significant differences in cognitive function were detected, although the treatment group showed less hippocampal volume loss. The negative results were disappointing in light of promising phase 2 clinical trial data suggesting up to 70% reduction of Aβ42 in the CSF [62], although interestingly, in post hoc analysis with ApoE subclassification, e4 homozygotes show statistically significant improvement in ADAS-cog score [89].

Semagacestat

Semagacestat or LY450139 is a small molecule gamma-secretase inhibitor that acts by functional inhibition rather than competitively inhibiting enzyme complex active sites [90]. The precise mechanism of action is unclear; given gamma-secretase inhibition, it is not specific to any Aβ aggregation state or conformation, but theoretically reduces proteolytic cleavage of transmembrane domain of AβPP and consequently release of Aβ42. Semagacestat has been shown to reduce Aβ in brain, CSF, and plasma of PDAPP transgenic mice with human APP V717F mutation [90]. Phase 1 studies in normal human volunteers showed a dose-dependent reduction in plasma Aβ42 [91], whereas subjects with mild to moderate AD showed a reduction in plasma but not CSF Aβ in a small phase 2 cohort study [92].

In a phase 3 clinical trial, 1537 subjects with probable AD were randomized to 100 mg or 140 mg Semagacestat, or a placebo dose, daily. Primary outcome measure was cognitive function based on ADAS-cog and ADCS-ADL. The ADAS-cog and ADCS-ADL scores worsened in all groups. ADCS-ADL scores in the high dose group were significantly worse than placebo (p < 0.001). Significant side effects were also noted in the treatment groups, including weight loss, skin cancers, infections, and laboratory test abnormalities. Withdrawal from the trial due to adverse events was also significantly more frequent in the treatment group (P < 0.001).

The Semagacestat trials and related studies have since been criticized for lack of rigorous preclinical characterization of Semagacestat as an effective or reliable Aβ lowering agent and its low therapeutic index [63]. It has since been termed a “pseudo-inhibitor” of gamma secretase [93]. A shift in direction may be the pursuit of gamma-secretase modulators that alter the cleavage site to produce an ostensibly more benign, non-amyloidogenic Aβ species while leaving proteolytic function intact [63].

Tarenflurbil

Tarenflurbil or Flurizan is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent that is said to modulate (rather than inhibit) gamma secretase by apparently shifting cleavage sites in favor of shorter, more benign Aβ species [94], but does not alter diverse functions associated with Notch processing [95]. Tarenflurbil reduces Aβ42 production in cell culture and experimental models [96], although dose responses were not established in vitro [62]. Subsequent studies in Tg2576 mice showed limited modulation of Aβ42 production [97]. Efficacy in AD treatment may also be limited by its greater inhibition of COX1 than Aβ42 [97].

While conclusions of specificity of Tarenflurbil for its proposed Aβ42 modulation may have been premature, a multicenter phase 3 clinical trial of mild AD was undertaken [98]. Eligible participants were randomized to placebo, 400 and 800 mg tarenflurbil. Primary outcomes included ADAS-Cog and ADCS-ADL. CDR-sb, mini-mental status exam (MMSE), Neuropsychiatric inventory, quality of life scale, Caregiver Burden Inventory, and 70-point version of ADAS-Cog were secondary outcomes. No difference in primary outcomes was detected in tarenflurbil treatment groups versus placebo. Secondary outcome analyses showed either no difference or marginally favored the placebo group. Some adverse events were more frequent in treatment groups, such as dizziness, anemia, pneumonia, herpes zoster, gastrointestinal ulcer, and eosinophilia. Tarenflurbil treatment groups were more likely to discontinue the study because of an adverse event. The placebo group was more likely to experience a stroke or a transient ischemic attack. Due to the combined negative outcomes with tarenflurbril, the clinical trials were terminated and compound discontinued.

Verubecestat

The development of different small molecules functioning as beta-secretase (BACE1) inhibitors was slowed somewhat by the challenge of targeting a large active site in intact neurons [63, 99]. However, through application structure-based rational design and screening, researchers discovered verubecestat (also known as MK-8931 or MK-8931-009), and confirmed hydrogen bonding interactions with the BACE1 catalytic site [100]. Verubecestat shows inhibition of production of Aβ40, Aβ42, and sAPPβ in vitro, and is a potent inhibitor of mouse BACE1 as well as purified human BACE2 [101]. Verubecestat reduces plasma, CSF, and cortical Aβ40 in rats and cynomolgus monkeys. Once-daily oral administration to cynomolgus monkeys for 9 months produced reduction of CSF Aβ40, Aβ42, and sAPPβ, and cortical Aβ40 and sAPPβ. Chronic administration in animal models was well tolerated.

In a phase 3 clinical trial, 1958 subjects with mild to moderate AD were randomized to 12 or 40 mg per day Verubecestat, and placebo [101]. Primary outcomes included ADAS-cog and ADCS-ADL. The trial was terminated for futility, with no differences in primary outcome between treatment and placebo groups. A number of adverse events were more common in the verubecestat groups, including rash, falls and injuries, sleep disturbance, suicidal ideation, weight loss, and hair color change.

Lanabecestat

Lanabecestat (AZD3293 or LY3314814) is a selective human BACE1 inhibitor shown to reduce plasma, CSF, and brain Aβ40, Aβ42, and sAPPβ in mouse, guinea pig, and dog models. It was reasonably well tolerated in a phase I study demonstrating a dose-dependent reduction of CSF Aβ [102]. A phase 3 trial was recently terminated due to futility. The specific results have not been published at the time of this writing.

Aducanumab

This monoclonal IgG1 antibody designed to selectively target aggregated Aβ epitopes to slow neurodegeneration and reduce AD progression has reached phase 3 trials. Initially, the antibody showed reduction of soluble and insoluble Aβ in the brain of Tg2576 mice in a dose-dependent manner, followed by significant reduction in brain Aβ in patients with prodromal or mild AD in a time (up to 54 weeks of treatment) and dose (1, 3, 6 or 10 mg/kg) dependent manner, as measured by PET imaging and showing some signs to slow the rate of cognitive decline [103, 104]. Some adverse events caused withdrawal of a subset of patients. Overall, the study concluded that aducanumab reduces brain Aβ plaques with some clinical benefit. Ongoing phase 3 trials will continue until the end of 2022 (trials NCT02477800 and NCT02484547) at sites of North America, Australia, Europe and Asia in 1350 patients with early AD [105]. Outcomes will focus on efficacy of monthly doses of aducanumab in treatment of AD symptoms and cognitive changes on patients.

Noteworthy Phase 2 trials

AN-1792

Although it did not progress to phase 3, AN-1792 or AIP 001 an active immunization formulation deserves mention. In a seminal study, Schenk et al. immunized PDAPP transgenic mice with synthetic Aβ42 before the onset of Aβ plaque deposition and at an older age when plaques are well established [106]. Immunization of younger mice prevented Aβ plaque deposition, neuritic dystrophy, and gliosis, while immunization of older mice markedly reduced AD pathology. These preclinical results not surprisingly met with considerable enthusiasm for disease modification in AD. A Phase 1 study in AD patients subsequently showed acceptable tolerability of Aβ42 (AN-1792) with QS-21 as adjuvant. 372 patients with mild to moderate AD were then randomized to IM injections of AN-1792 or placebo in a multicenter Phase 2 study, however, the study was terminated after early reports of meningoencephalitis. Follow-up revealed meningoencephalitis by clinical examination in 18 out of 298 (6%) study subjects [107], although it is difficult to know how many subjects were affected neuropathologically. One case examined at autopsy showed evidence of plaque clearing, but also showed extensive T cell infiltrates involving leptomeninges and parenchymal tissue, encompassing apparent immune-mediated attack on blood vessels (i.e. vasculitis) involved by CAA, as well as a subacute leukoencephalopathy [108]. Other cases showed convincing evidence of plaque clearing in the absence of meningoencephalitis, including one case of Lewy body dementia. Some follow-up studies suggested less functional decline in antibody responders, but the overall follow-up data, including neuropathological examination of eight subjects, pointed to no benefit from Aβ clearance[108]. Antibody response was also related to cerebral atrophy by MRI [109].

In retrospect, the active approaches to immunotherapy may have had the disadvantages of polyclonal antibody responses that are variable across patient populations and with age. This could lead to persistent adverse effects or blunted immune responses. Active approaches have therefore proceeded more slowly since the AN-1792 phase 2 trial. Several agents are in development, including ACC-001, CAD106, and Affitope AD02, and may be worth pursuing given the daunting cost and logistics of administering passive monoclonal antibody to a large population of AD patients [63].

BAN2401

BAN2401 is the humanized version of murine antibody mAb158, derived from immunization with Aβ-protofibrils containing the intra-Aβ Arctic mutation E22G. The Artic mutation has been shown to enhance Aβ protofibril formation in vitro, and intraneuronal Aβ accumulation in vivo. BAN2401 likewise shows selectivity for protofibrils compared to monomers, and greater binding affinity for protofibrils than fibrils [110]. Transgenic mice carrying Swedish and Artic mutations were cleared of senile plaques if BAN2401 was administered prior to the appearance of senile plaques in young mice, whereas older mice with established plaques showed no clearing of fibrillary Aβ. Lowering of protofibrillar Aβ (i.e., larger than 100 kDa) occurred in all age groups. In addition, researchers have suggested that Artic mutation carriers lack fibrillar Aβ based on PET imaging studies using Pittsburgh Compound B, which is consistent with neuropathological investigations demonstrating morphologically atypical Aβ plaques with relatively limited Congo red staining in autopsy brain of symptomatic patients. Taken together, these data suggest that BAN2401 is relatively specific for protofibrillar Aβ.

Safety and tolerability of BAN2401 in mild to moderate AD were investigated and found to be acceptable across a range of doses tested [110]. A recent phase 2 clinical trial of 856 patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to AD, or mild AD with evidence of brain amyloid by PET imaging were randomized to one of different five dose regimens: 2.5 mg/kg biweekly, 5 mg/kg monthly, 5 mg/kg biweekly, 10 mg/kg monthly and 10 mg/kg biweekly, or placebo. Outcome measures determined at 18 months included predefined conventional statistics on ADCOMS, ADAS-Cog, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Incidence of ARIA-E (edema) was less than 15% in patients with ApoE e4 alleles at the highest dose tested, although substantially fewer patients with e4 alleles received the highest dose because of the association between ARIA-E and e4 alleles. Reduction in amyloid on PET imaging was also demonstrated with treatment. Statistically significant slowing of disease progression was noted only with the highest treatment dose; however, the failure to normalize for ApoE genotype in the high dose group mitigates those results. The treatment with antibody ΒAN2401 (mAb158) rescued neuronal Aβ-induced death and substantially reduced accumulation of Aβ in astrocytes in co-cultures from embryonic cortex of C57/BL6 mice [111]. Recent data related to the BAN2401 phase II trials suggested cognitive benefit, but normalizing patients treatment groups to APOE4+revealed that treated group had similar decline rates than placebo controls [112]. The study evaluated safety, tolerability and efficacy of BAN2401 (clinitrialtrials.gov: NCT01767311) for over 18 months in 856 patients with MCI showed dose-dependent Aβ reduction and 26–30% slowing of cognitive decline. The outcomes of this trial revealed acceptable tolerability overall, although specific data were not available as a function of APOE.

BAN2401 results are significant in that proof of concept, or reduction in brain amyloid by PET imaging, is demonstrated, but with arguable clinical/therapeutic efficacy as noted, suggesting both the existence and the clinical insignificance of the amyloid cascade. It is also noteworthy that clinical trial strategies targeting amyloid-β increasingly steer away e4 alleles, despite e4 being the most significance genetic risk factor for developing AD, and having a close relationship with Aβ aggregation. The challenge of targeting a process that bridges normal cellular physiology and manifest as insoluble deposits is becoming increasingly apparent.

Failure of construct versus the null hypothesis

The remarkable amount of past and on-going efforts to target Aβ by a variety of mechanisms are evidence that Aβ neurotoxicity is settled science, yet outcomes from many clinical trials tend to suggest otherwise. It may be useful to recall that the foundation for all proteinopathy constructs lies in hallmark lesions, which are entirely empirical observations. SP and NFT are evidence only that some complex processes have taken place in the affected brain areas. This is as opposed to neoplasia, for example, in which morphology captures the essence of the disease, and presents an unambiguous target. SP and NFT occur in parallel with the essence of the disease, which is neurodegeneration, and present a less clear or specific target. Strictly speaking, the notion that hallmark lesions in AD represent neurotoxicity, or surrogates for targetable neurotoxic protein species, is still theoretical.

The above is the case despite the enormous superstructure assembled since identification of lesion constituents. The complex data concerning such phenomena as low-n assembly intermediates or self-propagating Aβ prions, tend more to highlight the malleability of the original hypothesis, founded in Mendelian genetics [1], for example, and revised over time to encompass purely post-translational phenomena, such as oligomers [39] and non-Mendelian, prion-like transmission of phenotypic information [10, 113]. Collective strategies that target the spectrum of Aβ species, from soluble Aβ, to insoluble Aβ, to both soluble and insoluble Aβ, to Aβ production, are de facto admissions that Aβ theory is instead unsettled. The spectrum of approaches further indicates that a broad diversity of Aβ mechanisms remain in play, for example that Aβ senile plaques sequester toxic oligomers and many other functional components of the neurons until a physical limit is reached [46], or alternatively that Aβ plaques are poorly soluble, benign aggregates, downstream from toxic soluble mediators [63]. This remains the case despite repeated demonstrations that Aβ lowering does not modify disease.

Outcome data in clinical trials are often viewed as evidence for or against the amyloid cascade hypothesis, but this may be a false dichotomy. A negative trial may, in some cases, indicate proof of concept, i.e. the existence of the amyloid cascade, and no disease modification. This would suggest that complex biological processes not fully understood mute the impact of the amyloid cascade on disease expression, or that Aβ metabolism on balance may have a partly protective role in the relentless neurodegeneration of AD. New adverse phenomena, such as ApoE e4 carrier susceptibility to ARIA-E [73] and other adverse reactions to therapy [107], in the face of target engagement [90], Aβ reduction [71, 86], plaque clearance [108], and unaltered neurological deterioration [70, 76, 86, 88, 90, 101], suggest that this may be the case. Alternatively, failure may be partly explained by deficiencies in the clinical studies. This includes, but are not limited to, suboptimal trial design, inadequate dosing, recruitment of patients at advanced stages of AD, genetic heterogeneity of selected patients, inconsistencies in cognitive assessment, and inadequate target engagement [114, 115].

Conclusions

Aβ-targeted therapeutic constructs rely on the amyloid cascade hypothesis and the inherent neurotoxicity of Aβ, for which there is an abundance of supporting literature. Nevertheless, a significant body of cumulative data now exists from the highest evidence base—randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trials—demonstrating target engagement and Aβ clearing, with no clinical benefit. If the scientific mode of inquiry is to challenge theory with observation, the neuroscience field seems obligated to revise the original theory, or discard Aβ altogether as the primary driver of neurodegeneration in AD.

References

Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–5.

Mann DMA, Esiri MM. The pattern of acquisition of plaques and tangles in the brains of patients under 50 years of age with Down’s syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1989;89:169–79.

Goate A, Chartier-Harlin M-C, Mullan M, Brown J, Crawford F, Fidani L, et al. Segregation of a missense mutation in the amyloid precursor protein gene with familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1991;349:704–6.

(No authors listed). Molecular classification of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 1991;337:1342–3.

Johnson DS, Li YM, Pettersson M, St George-Hyslop PH. Structural and chemical biology of presenilin complexes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2017;7:25.

Scheuner D, Eckman C, Jensen M, Song X, Citron M, Suzuki N, et al. Secreted amyloid β-protein similar to that in the senile plaques of Alzheimer’s disease is increased in vivo by the presenilin 1 and 2 and APP mutations linked to familial Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med. 1996;2:864–70.

Tamaoka A, Odaka A, Ishibashi Y, Usami M, Sahara N, Suzuki N, et al. APP717 missense mutation affects the ratio of amyloid beta protein species (A beta 1-42/43 and a beta 1-40) in familial Alzheimer’s disease brain. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:32721–4.

Younkin SG. Evidence that Aβ42 is the real culprit in alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:287–8.

Gravina SA, Ho L, Eckman CB, Long KE, Otvos L, Younkin LH, et al. Amyloid Beta protein (ABeta) in Alzheimer’s disease brain: biochemical and immunocytochemical analysis with antibodies specific for forms ending at ABeta40 or ABeta42(43). J Biol Chem. 1995;270:7013–6.

Cohen ML, Kim C, Haldiman T, ElHag M, Mehndiratta P, Pichet T, et al. Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease features distinct structures of amyloid-β. Brain. 2015;138:1009–22.

Shinkai Y, Yoshimura M, Ito Y, Odaka A, Suzuki N, Yanagisawa K, et al. Amyloid β‐proteins 1-40 and 1-42(43) in the soluble fraction of extra‐ and intracranial blood vessels. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:421–8.

Joachim CL, Duffy LK, Morris JH, Selkoe DJ. Protein chemical and immunocytochemical studies of meningovascular beta-amyloid protein in Alzheimer’s disease and normal aging. Brain Res. 1988;474:100–11.

Snyder SW, Ladror US, Wade WS, Wang GT, Barrett LW, Matayoshi ED, et al. Amyloid-beta aggregation: selective inhibition of aggregation in mixtures of amyloid with different chain lengths. Biophys J. 1994;67:1216–28.

Kim J, Onstead L, Randle S, Price R, Smithson L, Zwizinski C, et al. J Neurosci. 2007;27:627–33.

Ai Y, Zhenyu Y. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease: an update. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:55–78.

Shore VG, Shore B. Heterogeneity of human plasma very low density lipoproteins. separation of species differing in protein components. Biochemistry. 1973;12:502–7.

Pericak-Vance MA, Bebout JL, Gaskell PC, Yamaoka LH, Hung WY, Alberts MJ. Linkage studies in familial Alzheimer disease: evidence for chromosome 19 linkage. Am J Hum Genet. 1991;48:1034–50.

Strittmatter WJ, Saunders AM, Schmechel D, Pericak-Vance M, Enghild J, Salvesen GS, et al. Apolipoprotein E: high-avidity binding to beta-amyloid and increased frequency of type 4 allele in late-onset familial Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1977–81.

Mahley RW, Huang Y. Small-Molecule structure correctors target abnormal protein structure and function: Structure corrector rescue of apolipoprotein E4-associated neuropathology. J Med Chem. 2012;55:8997–9008.

Bu G, Apolipoprotein E. and its receptors in Alzheimer’s disease: pathway, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurosc. 2009;10:333–44.

Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. ApoE and Aβ in Alzheimer’s disease: accidental encounters or partners? Neuron. 2014;81:740–54.

Morrow JA, Hatters DM, Lu B, Höchtl P, Oberg KA, Rupp B, et al. Apolipoprotein E4 forms a molten globule: A potential basis for its association with disease. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:50380–5.

Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–3.

Chartier-Hariln M-C, Parfitt M, Legrain S, Pérez-Tur J, Brousseau T, Evans A, et al. Apolipoprotein-E, Epsilon-4 Allele as a major risk factor for sporadic early and late-onset forms of alzheimers-disease—analysis of the 19Q13.2 chromosomal region. Hum Mol Genet. 1994;3:569–74.

Mahley RW, Huang Y. Apolipoprotein E Sets the stage: response to injury triggers neuropathology. Neuron. 2012;76:871–85.

Yu J-T, Tan L, Hardy J. Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s Disease: an update. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014;37:79–100.

Aleshkov S, Abraham CR, Zannis VI. Interaction of nascent Apoe2, Apoe3, and Apoe4 isoforms expressed in mammalian cells with amyloid peptide beta (1–40). relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Biochemistry. 1997;36:10571–80.

Jiang Q, Lee CYD, Mandrekar S, Wilkinson B, Cramer P, Zelcer N, et al. ApoE promotes the proteolytic degradation of Aβ. Neuron. 2008;58:681–93.

Cerf E, Gustot A, Goormaghtigh E, Ruysschaert J-M, Raussens V. High ability of apolipoprotein E4 to stabilize amyloid- peptide oligomers, the pathological entities responsible for Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2011;25:1585–95.

Ungar L, Altmann A, Greicius MD. Apolipoprotein E, gender, and Alzheimer’s disease: an overlooked, but potent and promising interaction. Brain Imaging Behav. 2014;8:262–73.

Raber J, Wong D, Buttini M, Orth M, Bellosta S, Pitas RE, et al. Isoform-specific effects of human apolipoprotein E on brain function revealed in ApoE knockout mice: increased susceptibility of females. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10914–9.

Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, et al. The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA. 1998;279:751–5.

Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, Hyman B, Kukull WA, Mayeux R, et al. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer disease meta analysis consortium. JAMA. 1997;278:1349–56.

Corder EH, Saunders AM, Risch NJ, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, et al. Protective effect of apolipoprotein E type 2 allele for late onset Alzheimer disease. Nat Genet. 1994;7:180–4.

Yamazaki Y, Painter MM, Bu G, Kanekiyo T. Apolipoprotein E as a therapeutic target in alzheimer’s disease: a review of basic research and clinical evidence. CNS Drugs. 2016;30:773–89.

Cruchaga C, Kauwe JSK, Nowotny P, Bales K, Pickering EH, Mayo K, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid APOE levels: an endophenotype for genetic studies for Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4558–71.

Nelson PT, Alafuzoff I, Bigio EH, Bouras C, Braak H, Cairns NJ, et al. Correlation of alzheimer disease neuropathologic changes with cognitive status: a review of the literature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:362–81.

Hardy J. Alzheimer’s disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis: an update and reappraisal. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;9:151–3.

Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, et al. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid β protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416:535–9.

Kuo YM, Emmerling MR, Vigo-Pelfrey C, Kasunic TC, Kirkpatrick JB, Murdoch GH, et al. Water-soluble Abeta (N-40, N-42) oligomers in normal and Alzheimer disease brains. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4077–81.

Ono K, Condron MM, Teplow DB. Structure-neurotoxicity relationships of amyloid -protein oligomers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14745–50.

Shankar GM, Li S, Mehta TH, Garcia-Munoz A, Shepardson NE, Smith I, et al. Amyloid-β protein dimers isolated directly from Alzheimer’s brains impair synaptic plasticity and memory. Nat Med. 2008;14:837–42.

Koffie RM, Meyer-Luehmann M, Hashimoto T, Adams KW, Mielke ML, Garcia-Alloza M, et al. Oligomeric amyloid associates with postsynaptic densities and correlates with excitatory synapse loss near senile plaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:4012–7.

Darocha-Souto B, Scotton TC, Coma M, Serrano-Pozo A, Hashimoto T, Serenó L, et al. Brain oligomeric β-amyloid but not total amyloid plaque burden correlates with neuronal loss and astrocyte inflammatory response in amyloid precursor protein/tau transgenic mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:360–76.

Esparza TJ, Zhao H, Cirrito JR, Cairns NJ, Bateman RJ, Holtzman DM, et al. Amyloid-beta oligomerization in Alzheimer dementia versus high-pathology controls. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:104–19.

Hong S, Ostaszewski BL, Yang T, O’Malley TT, Jin M, Yanagisawa K, et al. Soluble Aβ oligomers are rapidly sequestered from brain ISF in vivo and bind GM1 ganglioside on cellular membranes. Neuron. 2014;82:308–19.

Mroczko B, Groblewska M, Litman-Zawadzka A, Kornhuber J, Lewczuk P. Amyloid β oligomers (AβOs) in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2018;125:177–91.

Benilova I, Karran E, De Strooper B. The toxic Aβ oligomer and Alzheimer’s disease: An emperor in need of clothes. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:349–57.

Langer F, Eisele YS, Fritschi SK, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Soluble A beta seeds are potent inducers of cerebral beta -amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14488–95.

Jarrett JT, Lansbury PT. Seeding “one-dimensional crystallization” of amyloid: a pathogenic mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease and scrapie? Cell. 1993;73:1055–8.

Petkova AT, Leapman RD, Guo Z, Yau WM, Mattson MP. Tycko R. Self-propagating, molecular-level polymorphism in Alzheimer’s β-amyloid fibrils. Science. 2005;307:262–5.

Hamaguchi T, Eisele YS, Varvel NH, Lamb BT, Walker LC, Jucker M. The presence of Aβ seeds, and not age per se, is critical to the initiation of Aβ deposition in the brain. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:31–7.

Kovacs GG, Lutz MI, Ricken G, Strobel T, Hoftberger R, Preusser M, et al. Dura mater is a potential source of Abeta seeds. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:911–23.

Giaccone G, Mangieri M, Capobianco R, Limido L, Hauw JJ, Haïk S, et al. Tauopathy in human and experimental variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:1864–73.

Pillai JA, Appleby BS, Safar J, Leverenz JB. Rapidly progressive Alzheimer’s disease in two distinct autopsy cohorts. Neurology. 2016;86:183.

Parchi P, Castellani R, Capellari S, Ghetti B, Young K, Chen SG, et al. Molecular basis of phenotypic variability in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:767–78.

Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, Brown P, Schulz-Schaeffer W, Windl O. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:224–33.

Mez J, Chung J, Jun G, Kriegel J, Bourlas AP, Sherva R, et al. Two novel loci, COBL and SLC10A2, for Alzheimer’s disease in African Americans. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017;13:119–29.

Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1452–8.

Murray ME, Graff-Radford NR, Ross OA, Petersen RC, Duara R, Dickson DW. Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer’s disease with distinct clinical characteristics: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2001;10:785–96.

Lannfelt L, Relkin NR, Siemers ER. Amyloid-ß-directed immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease. J Intern Med. 2014;275:284–95.

Karran E, Hardy J. A critique of the drug discovery and phase 3 clinical programs targeting the amyloid hypothesis for Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:185–205.

Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8:595–608.

Cummings J, Ritter A, Zhong K. Clinical trials for disease-modifying therapies in alzheimer’s disease: a primer, lessons learned, and a blueprint for the future. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2018;64:S3–22.

Brody DL, Holtzman DM. Active and passive immunotherapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2008;31:175–93.

Lannfelt L, Moller C, Basun H, Osswald G, Sehlin D, Satlin A, et al. Perspectives on future Alzheimer therapies: amyloid-beta protofibrils - a new target for immunotherapy with BAN2401 in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6:16.

Zhao J, Nussinov R, Ma B. Mechanisms of recognition of amyloid-β (Aβ) monomer, oligomer, and fibril by homologous antibodies. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:18325–43.

Szabo P, Mujalli DM, Rotondi ML, Sharma R, Weber A, Schwarz HP, et al. Measurement of anti-beta amyloid antibodies in human blood. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;227:167–74.

Salloway S, Sperling R, Gilman S, Fox NC, Blennow K, Raskind M, et al. A phase 2 multiple ascending dose trial of bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:2061–70.

Abushouk AI, Elmaraezy A, Aglan A, Salama R, Fouda S, Fouda R, et al. Bapineuzumab for mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Neurol. 2017;17:66.

Russu A, Samtani MN, Xu S, Adedokun OJ, Lu M, Ito K, et al. Biomarker exposure-response analysis in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease trials of bapineuzumab. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;53:535–46.

Novak G, Fox N, Clegg S, Nielsen C, Einstein S, Lu Y, et al. Changes in brain volume with bapineuzumab in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015;49:1123–34.

Ketter N, Brashear HR, Bogert J, Di J, Miaux Y, Gass A, et al. Central review of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in two phase III clinical trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease patients. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;57:557–73.

Sperling RA, Jack CR, Black SE, Frosch MP, Greenberg SM, Hyman BT, et al. Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities in amyloid-modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2011;7:367–85.

DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart J-C, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A antibody alters CNS and plasma A clearance and decreases brain A burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8850–5.

Salloway S, Sperling R, Fox NC, Blennow K, Klunk W, Raskind M, et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:322–33.

DeMattos RB, Lu J, Tang Y, Racke MM, DeLong CA, Tzaferis JA, et al. A plaque-specific antibody clears existing β-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease mice. Neuron. 2012;76:908–20.

Cline EN, Bicca MA, Viola KL, Klein WL. The Amyloid-β oligomer hypothesis: beginning of the third decade. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:S567–610.

Du Y, Dodel R, Hampel H, Buerger K, Lin S, Eastwood B, et al. Reduced levels of amyloid beta-peptide antibody in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2001;57:801–5.

Dodel R, Hampel H, Depboylu C, Lin S, Gao F, Schock S, et al. Human antibodies against amyloid peptide: a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:220–3.

Fillit H, Hess G, Hill J, Bonnet P, Toso C. IV immunoglobulin is associated with a reduced risk of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Neurology. 2009;73:180–5.

Du Y, Wei X, Dodel R, Sommer N, Hampel H, Gao F, et al. Human anti-beta-amyloid antibodies block beta-amyloid fibril formation and prevent beta-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity. Brain. 2003;126:1935–9.

Karran E, Mercken M, De Strooper B. The amyloid cascade hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease: an appraisal for the development of therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:698–712.

Magga J, Puli L, Pihlaja R, Kanninen K, Neulamaa S, Malm T, et al. Human intravenous immunoglobulin provides protection against Abeta toxicity by multiple mechanisms in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroinflamm. 2010;7:90.

Bacher M, Depboylu C, Du Y, Noelker C, Staufenbiel M, Behr T, et al. Peripheral and central biodistribution of (111)In-labeled anti-beta-amyloid antibodies in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci Lett. 2009;449:240–5.

Relkin NR, Thomas RG, Rissman RA, Brewer JB, Rafii MS, Van Dyck CH, et al. A phase 3 trial of IV immunoglobulin for Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2017;88:1768–75.

Martineau E, de Guzman JM, Rodionova L, Kong X, Mayer PM, Aman AM. Investigation of the noncovalent interactions between anti-amyloid agents and amyloid β peptides by ESI-MS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2010;21:1506–14.

Aisen PS, Gauthier S, Ferris SH, Saumier D, Haine D, Garceau D, et al. Tramiprosate in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multi-centre study (the alphase study). Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:102–11.

Abushakra S, Porsteinsson A, Vellas B, Cummings J, Gauthier S, Hey JA. Clinical benefits of tramiprosate in Alzheimer’s Disease are associated with higher number of APOE4 Alleles: the “ APOE4 gene- dose effect. J Prev Alz Dis. 2016;33:219–28.

Doody R, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, et al. A Phase 3 trial of semagacestat for treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:341–50.

Siemers E, Skinner M, Dean RA, Gonzales C, Satterwhite J, Farlow M, et al. Safety, tolerability, and changes in amyloid beta concentrations after administration of a gamma-secretase inhibitor in volunteers. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2005;28:126–32.

Fleisher AS, Raman R, Siemers ER, Becerra L, Clark CM, Dean R, et al. Phase 2 safety trial targeting amyloid beta production with a gamma-secretase inhibitor in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1031–8.

Tagami S, Yanagida K, Kodama TS, Takami M, Mizuta N, Oyama H, et al. Semagacestat Is a Pseudo-Inhibitor of γ-Secretase. Cell Rep. 2017;21:259–73.

Borgegard T, Jureus A, Olsson F, Rosqvist S, Sabirsh A, Rotticci D, et al. First and second generation gamma-secretase modulators (GSMs) modulate amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide production through different mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:11810–9.

De Strooper B, Annaert W, Cupers P, Saftig P, Craessaerts K, Mumm JS, et al. A presenilin-1-dependent γ-secretase-like protease mediates release of notch intracellular domain. Nature. 1999;398:518–22.

Eriksen JL, Sagi SA, Smith TE, Weggen S, Das P, McLendon DC, et al. NSAIDs and enantiomers of flurbiprofen target g-secretase and lower Ab42 in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:440–9.

Peretto I, Radaelli S, Parini C, Zandi M, Raveglia LF, Dondio G, et al. Synthesis and biological activity of flurbiprofen analogues as selective inhibitors of beta-amyloid(1)(-)(42) secretion. J Med Chem2. 2005;48:5705–20.

Green RC, Schneider LS, Amato DA, Beelen AP, Wilcock G, Swabb EA, et al. Effect of tarenflurbil on cognitive decline and activities of daily living in patients with mild Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:2557–64.

Yan R, Vassar R. Targeting the β secretase BACE1 for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13:319–29.

Scott JD, Li SW, Brunskill APJ, Chen X, Cox K, Cumming JN, et al. Discovery of the 3-Imino-1,2,4-thiadiazinane 1,1-Dioxide derivative verubecestat (MK-8931)—Aβ-Site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 inhibitor for the treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. J Med Chem. 2016;59:10435–50.

Kennedy ME, Stamford AW, Chen X, Cox K, Cumming JN, Dockendorf MF, et al. The BACE1 inhibitor verubecestat (MK-8931) reduces CNS b-Amyloid in animal models and in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:363ra150.

Cebers G, Alexander RC, Haeberlein SB, Han D, Goldwater R, Ereshefsky L, et al. AZD3293: pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic effects in healthy subjects and patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2016;55:1039–53.

Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016;537:50–6.

Ferrero J, Williams L, Stella H, Leitermann K, Mikulskis A, O’Gorman J, et al. First-in-human, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-dose escalation of aducanumab (BIIB037) in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement NY. 2016;2:169–76.

Budd Haeberlein S, O’Gorman J, Chiao P, Bussière T, von Rosenstiel P, Tian Y, et al. Clinical development of aducanumab, an anti-Aβ human monoclonal antibody being investigated for the treatment of early Alzheimer’s disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 2017;4:255–63.

Schenk D, Barbour R, Dunn W, Gordon G, Grajeda H, Guido T, et al. Immunization with amyloid-beta attenuates Alzheimer-disease-like pathology in the PDAPP mouse. Nature. 1999;400:173–7.

Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JF, Laurent B, Puel M, Kirby LC, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Aβ42 immunization. Neurology. 2003;61:46–54.

Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, Bayer A, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer’s disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372:216–23.

Vellas B, Black R, Thal L, Fox N, Daniels M, McLennan G, et al. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2009;6:144–51.

Logovinsky V, Satlin A, Lai R, Swanson C, Kaplow J, Osswald G, et al. Safety and tolerability of BAN2401—a clinical study in Alzheimer’s disease with a protofibril selective Aβ antibody. Alzheimer’s Re Ther. 2016;8:14.

Sollvander S, Nikitidou E, Gallasch L, Zysk M, Soderberg L, Sehlin D, et al. The Aβ protofibril selective antibody mAb158 prevents accumulation of Aβ in astrocytes and rescues neurons from Aβ-induced cell death. J Neuroinflamm. 2018;15:98.

Lowe D. Alzheimer’s disease, more on BAN2401, unfortunately. Sci Trans Med, Blog Oct-25-2018 (http://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2018/10/25).

Cohen M, Appleby B, Safar JG. Distinct prion-like strains of amyloid beta implicated in phenotypic diversity of Alzheimer’s disease. Prion. 2016;10:9–17.

Mehta D, Jackson R, Paul G, Shi J, Sabbagh M. Why do trials for Alzheimer’s disease drugs keep failing? A discontinued drug perspective fro 2010–5. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2017;26:735–9.

Golde TE, DeKosky ST, Galasko D. Alzheimer’s disease: the right drug, the right time. Science. 2018;362:1250–1.

Acknowledgements

RCMI Program from NIH at UTSA (5G12RR013646, G12MD007591), Alzheimer’s Association (AARFD-17-529742), Semmes Foundation and Lowe Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castellani, R.J., Plascencia-Villa, G. & Perry, G. The amyloid cascade and Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics: theory versus observation. Lab Invest 99, 958–970 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-019-0231-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-019-0231-z

This article is cited by

-

Alzheimer’s disease – the journey of a healthy brain into organ failure

Molecular Neurodegeneration (2022)

-

Synthesis and evaluation of novel arylisoxazoles linked to tacrine moiety: in vitro and in vivo biological activities against Alzheimer’s disease

Molecular Diversity (2022)

-

N-Acetylcysteine prevents amyloid-β secretion in neurons derived from human pluripotent stem cells with trisomy 21

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Defective Lysosomal Lipid Catabolism as a Common Pathogenic Mechanism for Dementia

NeuroMolecular Medicine (2021)

-

Possible role of rice bran extract in microglial modulation through PPAR-gamma receptors in alzheimer’s disease mice model

Metabolic Brain Disease (2021)