Abstract

Respiratory failure is a major contributor to mortality and morbidity in newborn infants. The lung assist device (LAD) is a novel gas exchange device that supplements mechanical ventilation. The objective is to test the effect of the LAD on pulmonary histopathology in juvenile piglets with acute lung injury caused by saline lung lavage (SLL) followed by intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV). Three- to 4-wk-old piglets were randomized to no intervention (control group), SLL alone (SLL group), SLL + IMV (IMV group), or SLL + IMV + LAD (LAD group) (n = 6 per group). The carotid artery and jugular vein were cannulated and an arteriovenous circuit completed, and the LAD was inserted into this circuit. Gas exchange via the LAD was initiated by passage of 100% oxygen over the blood-carrying hollow fibers of the LAD. Hemodynamic variables were recorded. Mechanical ventilation was systematically weaned. Lung histology was scored by two observers masked to treatment group. There were no differences in hemodynamic variables between the study groups. There was a significant increase in the total lung injury score in the IMV group compared with the LAD group. The novel pumpless low-resistance LAD has shown feasibility and potential to decrease ventilator-induced lung injury in a juvenile animal model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Neonatal respiratory failure is a serious clinical problem (1–3) associated with high morbidity, mortality, and cost (4–6). The mainstay of management is supportive care with mechanical ventilation, and important adjunctive therapies include high-frequency ventilation, surfactant therapy, inhaled nitric oxide, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). Many term and preterm infants die due to cardiorespiratory failure despite maximal ventilatory support (3–10). It is well known that ventilatory support by itself may inflict lung injury (11,12). Animal and human studies indicate that volutrauma contributes to the development of lung injury (13–15). ECMO, a treatment of last resort for term or near-term neonates with profound cardiopulmonary disease, allows the lung to rest and recover, attenuating the often damaging effects of aggressive mechanical ventilation. However, ECMO is currently reserved for newborn infants with reversible pulmonary disease in whom conventional or high-frequency ventilation with inhaled nitric oxide has failed. This is due to serious inherent risks of ECMO, such as coagulopathy and the need for systemic anticoagulation, which predisposes to systemic and intracranial hemorrhage. An essential element in the ECMO circuit is a mechanical pump that directly leads to shear stress-induced injury of blood cells (16). The evolution of membrane and oxygenator technology has led to low-resistance membrane gas exchange devices that permit significant flow even when the circuit is not driven by a pump. Several investigators have reported the ability of these devices to partially support adult patients in respiratory failure. Gattinoni et al. (17) proved the efficacy and safety of extracorporeal carbon dioxide removal in combination with low-frequency ventilation. Flörchinger et al. (18) reported their successful 10-y institutional experience of using pumpless extracorporeal lung assist devices (LAD) to support patients with deteriorating gas exchange for prolonged periods. In a prospective, randomized, unblinded study, the LAD decreased ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) and improved 5-d survival in a severe acute respiratory distress syndrome(ARDS) model in adult sheep (19). We tested the hypothesis that the LAD would reduce lung damage in a model of acute lung injury in juvenile piglets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham approved the research protocol. All animal care and handling was in accordance with the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health.

Surgery.

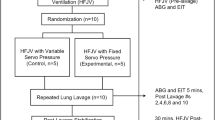

Three- to 4-wk-old piglets were endotracheally intubated and mechanically ventilated using an Infant Star ventilator (Infant Star 950, Nellcor Puritan Bennett, Pleasanton, CA) and maintained on general anesthesia using 1.5–5% isoflurane titrated to keep animals deeply sedated. Animals were placed on a table with a heating pad to maintain body temperature at 37–38°C. Five French catheters were inserted into the thoracic aorta via the right femoral artery for measurement of systemic arterial pressure and into the inferior vena cava via the right femoral vein for measurement of central venous pressure. After a left third to fourth interspace thoracotomy, a 10- or 12-mm ultrasonic flow transducer (T101, Transonic systems, Ithaca, NY) was affixed around the main pulmonary artery to measure cardiac output (20). The left carotid artery and internal jugular vein were surgically exposed and cannulated with low-resistance catheters (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN) of 8F and 10F diameters, respectively. The LAD was primed with 60 mL of heparinized normal saline, debubbled of air, and attached to the vascular cannulae. Another ultrasonic flow transducer (HT110, Transonic systems, Ithaca, NY) was placed on the outflow tubing to measure blood flow through the LAD. Animals were anticoagulated with a bolus of 50 units/kg of heparin after cannulation and maintained on a heparin infusion at a rate of 100 units/h. After surgery, study animals were observed for 30 min to allow for stabilization (Fig. 1).

Experimental protocols.

Twenty-four juvenile piglets were assigned to four groups (n = 6 per group): 1) Controls (control group): piglets did not receive lung lavage but were acutely instrumented and ventilated at very low settings during the surgical procedure. Animals were killed at the end of surgery. 2) Saline lavage-alone [SLL group (saline lung lavage)]: piglets were acutely instrumented, ventilated at very low settings during the surgical procedure, and received lung lavage. Animals were killed immediately after lavage. 3) Lavage followed by IMV (IMV group): piglets were instrumented and received lung lavage followed by conventional intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV). 4) Lavage followed by IMV, combined with LAD (LAD group): piglets were instrumented and received lung lavage followed by IMV and LAD support.

Acute lung injury was induced by repeated lung lavages at 5-min intervals using 0.9% warm saline (30 mL/kg). Lavages were continued until partial pressure of arterial oxygen (Pao2) values decreased to less than 60 torr at FiO2 1.0 and there was a minimum reduction of 30% in dynamic lung compliance. Postlavage, initial ventilatory settings were positive inspiratory pressure (PIP) = 12 cm H2O, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) = 4 cm H2O, respiratory rate (RR) = 24 breaths/min, and FiO2 = 1.0. The PEEP was maintained at 4 cm H2O throughout the experiments. In both the IMV and LAD groups, PIP was adjusted by 20% increments to reach a tidal volume of 6 mL/kg. Once the targeted tidal volume was achieved, respiratory rate was reduced to attempt to maintain partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (Paco2) in the 45–55 torr range. Concurrently, FiO2 was reduced to keep Pao2 above 60 torr (Fig. 2). Sweep gas flow through the LAD (100% O2) was controlled by a flow meter and set at 1.5–2 times blood flow through the device. The goal pH was 7.20–7.35. The duration of the experiment was limited to 6 h.

Measurements.

Throughout the experiment, heart rate (physiologic recorders; Gould-Brush 2400S, Oxnard, CA), systemic arterial pressure, pulmonary arterial pressure (pressure transducers; Spectramed P23XL, Oxnard, CA), oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry (N-100 C, Nellcor, Pleasanton, CA), pulmonary artery flow, and blood flow through the LAD by flow transducers were continuously recorded. Lung compliance and tidal volume were measured and recorded using a Bicore pulmonary function apparatus (Bicore, Pulmonary Monitor CP-100, Irvine, CA), which used a pneumotachograph attached to the endotracheal tube adapter.

Blood samples.

Arterial as well as pre and postdevice blood gases were monitored at baseline, 30 min after lung injury, and 15 min after changes in ventilatory settings using a blood gas analyzer (ABL 700 series, Radiometer America Inc., Westlake, OH).

Histologic assessment.

After the animals were killed at the conclusion of the experiment with an overdose of pentobarbital, the trachea was clamped at end-expiration with a PEEP of 5 cm H2O, and the lungs were removed en bloc. Lungs were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, transferred to 70% alcohol, and paraffin-embedded. Five micrometer-thick lung sections were prepared from the cranial dorsal (nondependent) and caudal ventral (dependent) regions. Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections were scored using a semiquantitative scoring system by two independent observers blinded to the treatment group (21–24). Variables scored were alveolar and interstitial inflammation, alveolar and interstitial hemorrhage, edema, atelectasis, and necrosis. Severity of injury was graded by the following scale: no injury = 0; injury to 25% of the field = 1; injury to 50% of the field = 2; injury to 75% of the field = 3; and diffuse injury = 4. Ten random fields from each section were examined at 40× magnification to minimize the effect of regional variation. Injury scores were averaged for analysis.

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as mean ± SEM and were displayed and analyzed by SigmaStat v. 3.5 (Jandel Scientific, San Rafael, CA). Lung injury scores were considered as the primary outcome and were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Tukey's test.

Hemodynamic variables, arterial blood gases, and pH were compared over time by repeated measures ANOVA. If significant differences were found by repeated measures ANOVA, multiple comparisons by Dunnett's test (for hemodynamic variables) or Tukey's test (for blood gases) were performed. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

One animal in each of the LAD and the IMV groups died shortly before the completion of the study. Data from these animals were included in analysis.

Hemodynamics.

Both the groups had similar baseline characteristics for body weight, hematocrit (Hct), heart rate (HR), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and cardiac output (CO). These variables remained statistically comparable among the groups at the end of the study. Cardiac output decreased in both the groups because of the natural course of the lung injury model (Fig. 3A and B). Blood flow through the LAD was constant and ranged from 14 to 32 mL/kg/min and averaged 26 mL/kg/min or 25% of cardiac output. Despite the arteriovenous shunt, the heart rate and MAP remained relatively constant and were not different from baseline.

Changes in heart rate (A) and cardiac output (B) of the LAD group compared with the IMV group during 6-h postlung lavage. Pre, baseline values before lung lavage; 0.5 h, 30-min postlavage and after LAD connection to the animal. All the values are mean ± SEM (p > 0.05). Filled circles represent the LAD group and open circles represent the IMV group.

Lung function.

Baseline Pao2/FiO2 ratio and pulmonary compliance (Cdyn) were similar in both the groups. Saline lavage caused profound pulmonary dysfunction as evidenced by a significant and similar decrease in Pao2/FiO2 ratio and decrease in Cdyn in all the animals.

PIP needed to be increased to maintain Pao2 and Paco2 in the IMV group. The LAD allowed significant reduction in PIP, tidal volume (VT), and FiO2 compared with the settings after lavage (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Target VT could be achieved in LAD group compared with IMV group. Paco2 remained higher than our target of 45–55 torr in both the groups and hence ventilatory rate was not reduced. Both the LAD and IMV groups developed mild respiratory acidosis compared with the control and SLL group, and the IMV group also developed metabolic acidosis (Table 1).

Changes in peak inspiratory pressure (A), tidal volume (B), and Pao2/FiO2 ratio (C) of the LAD group compared with the IMV group during 6 h. Pre, baseline values before lung lavage; 0.5 h, 30-min postlavage and after LAD connection to the animal. All the values are mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05). Filled circles represent the LAD group and open circles represent the IMV group.

Histology.

Lung lavage induced injury in the SLL group compared with the control group. Lungs of the IMV group demonstrated gross damage including edema with distinct emphysematous and hemorrhagic changes on the pleural surfaces. Lung injury scores were increased in the IMV group compared with the control, SLL, and LAD groups (Fig. 5; p < 0.05). Lungs from the IMV group demonstrated significantly thickened and congested alveolar walls, marked alveolar inflammation, and airway injury compared with the other three groups (Fig. 6). The LAD group had significantly less total lung injury scores, inflammatory response, and airway injury compared with the IMV group and was not statistically different compared with the control group (Figs. 5 and 6).

Comparison of lung injury scores among all the four groups revealing the raw data as a vertical dot plot superimposed on the box plot of the median of the total lung injury score with the 5th and 95th percentile of six animals in each group. TLIS, total lung injury score; Control, Control group; SLL, lavage-alone group; IMV, lavage followed by mechanical ventilation group; LAD, LAD group. *p < 0.05 for IMV group compared with the other three groups.

Photomicrographs of hematoxylin and eosin stained lung sections from Control piglets (A), piglets in lavage group receiving lung lavage only (B), piglets in IMV group receiving lung lavage and mechanical ventilation during 6 h (C), and piglets in LAD group receiving lung lavage, mechanical ventilation and supported by the LAD for 6 h (D).

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of a pumpless extracorporeal LAD on lung histopathology in a juvenile animal model of acute lung injury. It was designed to evaluate the combined effect of the LAD and a lung-protective ventilation strategy in an animal model of induced surfactant deficiency. This strategy depended on using a smaller tidal volume of 6 mL/kg and alveolar maintenance of lung volume by sufficient levels of PEEP. We aimed at maintaining a fixed PEEP that was enough to maintain lung expansion while decreasing tidal volume to prevent overinflation. Previous studies have shown that PEEP reduced severity of VILI and reduced damage produced by repeated opening and closing of lung units in surfactant deficient lungs; however, PEEP might favor hyperinflation if tidal volume was not reduced (25–27). The LAD coupled with low-frequency mechanical ventilation allowed for significant reductions in peak inspiratory pressures and tidal volumes, which were associated with reduced acute lung injury while achieving adequate gas exchange.

Recent technological advances have led to a new generation of low-resistance pumpless extracorporeal lung assist (pECLA) devices. These devices were developed to limit blood interaction with extracorporeal foreign surfaces and consumption of blood components secondary to shear stress, which are seen in ECMO (28–32). The LAD, a pECLA device, has sufficient membrane surface area for partial gas exchange. The LAD was shown to improve gas exchange and survival in adult animal models (33,34), and our study demonstrates that the LAD shows also preliminary feasibility and efficacy in a juvenile animal model.

The lung histology after lavage revealed diffuse involvement with alveolar hemorrhage, septal thickening, formation of hyaline membranes, increase in numbers of inflammatory cells within the intracellular space, and airway denudation. These findings are consistent with those described in acute lung injury models (35,36). Compared with the LAD and control groups, the IMV group demonstrated marked denudation of the airway epithelium either focally or diffusely, and a significant increase in the number of alveolar inflammatory cells. These differences are probably attributable to the significantly higher peak inspiratory pressures and tidal volumes that were necessary in the IMV group to achieve adequate gas exchange. This is consistent with literature that indicates that mechanical ventilation in animal models with high PIP (37) and large tidal volumes (36) leads to acute lung injury and ultimately to respiratory failure. These findings were supported by the large clinical, randomized trial conducted by the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute ARDS Clinical Network on Ventilator Management that revealed a 25% improvement in the outcome of patients managed with lower tidal volumes (38).

In our study, hemodynamic changes were similar in both the groups, with heart rate increasing and cardiac output and systemic arterial pressure decreasing during the course of the 6 h of the study. Mandava et al. (37) described systemic hypotension and decreased cardiac output in a similar RDS model. They attributed these changes to systemic capillary leak syndrome (SCLS) that manifests as intravascular volume depletion, hemoconcentration, and shock. They reported that SCLS developed as early as 2 h after starting IMV and evolved into a lethal form with cardiovascular collapse and death despite all supportive measures (37). Hypoxia was not the immediate cause of death. There was adequate response to epinephrine or to volume loading. These observations were very similar to ours. One animal died from each group of the study between the third and fourth hour after the induction of acute lung injury secondary to deterioration in cardiorespiratory status. This death rate was lower than the 50% rate described by Kaisers et al. (39) in juvenile pigs with lavage-induced respiratory distress syndrome.

The hemodynamic changes noted are unlikely to be secondary to the extracorporeal shunt, as they were comparable between the groups. Zwischenberger et al. (40) noted that despite a shunt of up to 25% of cardiac shunt through the LAD circuit for 7 d, there was no instability in the hemodynamic profile. Brunston et al. (41) showed that perfusion of vital organs was maintained within 80% of baseline in animals with an arteriovenous shunt of up to 25% of the cardiac output. In our study, the low-resistance LAD circuit allowed a blood flow of up to 32% of the cardiac output at a mean arterial blood pressure of around 70 mm Hg. Oxygen delivery and tissue perfusion were maintained as indicated by a normal oxygen saturation and lack of metabolic acidosis. Both arterial oxygen tension and mixed venous saturation were significantly higher in the LAD group than in the IMV group. The Pao2/FiO2 ratio, a reliable predictor of survival in ARDS (42), was higher in the LAD group at the end of the 6-h study. At the end of the experiment, the higher Paco2 than our target in both the LAD and IMV groups was probably related to the significant lung damage in addition to fluid retention in the airways caused by lavage. Allowing for permissive hypercapnia, we could achieve target VT of 6 mL/kg with less PIP, therefore reducing VILI.

One of the limitations of our study is that lung lavage does not accurately simulate RDS. However, the goal of this study was to test the effect of the LAD on VILI in a surfactant-deficient juvenile animal model, as many newborn pulmonary diseases are associated with surfactant deficiency being secondary to prematurity, pneumonia, or meconium aspiration. Repeated lavage with depletion of surfactant decreases lung compliance, impairs gas exchange, facilitates alveolar collapse, and increases the likelihood of mechanical injury to alveolar walls during repeated cycles of opening and closing during mechanical ventilation. Therefore, the surfactant-depletion model is useful for evaluation of VILI. Other animal models of ALI that have been reported in the literature include oleic acid, LPS, acid aspiration, hyperoxia, bleomycin, pulmonary ischemia-reperfusion, nonpulmonary ischemia reperfusion, i.v. bacteria, intrapulmonary bacteria, peritonitis, cecal ligation, and puncture. However, the advantage of the surfactant-depletion model is that it provides a useful way to test the effect of different ventilatory strategies on development of tissue injury because injury would result more from the ventilatory strategies than from the saline lavage. In contrast, the other methods such as acid aspiration lead to significant lung injury and the additional injury of larger tidal volumes may be harder to assess. The LAD is also dependent on cardiac output and hence cannot be expected to support gas exchange in cardiogenic shock or other conditions with poor cardiac output. Another limitation is that this study evaluated only the short-term effects of lung lavage and mechanical ventilation. Although it may not be optimal, this acute model of lung injury is supported by a good body of literature (43–49), and the promising short-term results demonstrate the feasibility for longer-term studies.

In conclusion, the LAD improved gas exchange and reduced VILI in juvenile piglets after lung lavage while maintaining normal hemodynamics. Future studies are required to improve the biocompatibility of the LAD, test long-term efficacy in chronically instrumented animals, and evaluate less invasive methods of using the LAD, such as connection to the umbilical vessels, which would increase the clinical relevance of the device.

Abbreviations

- ECMO:

-

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- IMV:

-

intermittent mandatory ventilation

- LAD:

-

lung assist device

- PIP:

-

peak inspiratory pressure

- VILI:

-

ventilator-induced lung injury

References

Chami M, Geoffray A 1997 A pulmonary sequelae of prematurity: radiological manifestations. Pediatr Pulmonol Suppl 16: 51

Chye JK, Gray PH 1995 Rehospitalization and growth of infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a matched control study. J Paediatr Child Health 31: 105–111

UK Collaborative ECMO Trial Group 1996 UK collaborative randomised trial of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Lancet 348: 75–82

1997 Economic outcome for intensive care of infants of birth weight 500–999 g born in Victoria in the post surfactant era. The Victorian Infant Collaborative Study Group. J Paediatr Child Health 33: 202–208

Vaucher YE, Dudell GG, Bejar R, Gist K 1996 Predictors of early childhood outcome in candidates for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr 128: 109–117

Walsh-Sukys MC, Bauer RE, Cornell DJ, Friedman HG, Stork EK, Hack M 1994 Severe respiratory failure in neonates: morbidity and mortality rates and neurodevelopmental outcomes. J Pediatr 125: 104–110

Halliday HL 2008 Surfactants: past, present and future. J Perinatol 28: S47–S56

Kinsella JP 2008 Inhaled nitric oxide in the term newborn. Early Hum Dev 84: 709–716

Kinsella JP, Abman SH 2007 Inhaled nitric oxide in the premature newborn. J Pediatr 151: 10–15

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, Griffin MF, Clark RH 2001 Epidemiology of neonatal respiratory failure in the United States. Projections from California and New York. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 1154–1160

Artigas A, Bernard GR, Carlet J, Dreyfuss D, Gattinoni L, Hudson L, Lamy M, Marini JJ, Matthay MA, Pinsky MR, Spragg R, Suter PM 1998 The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS, Part 2: Ventilatory, pharmacologic, supportive therapy, study design strategies, and issues related to recovery and remodeling. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 1332–1347

Clark RH, Gertsmann DR, Jobe AH, Moffitt ST, Slutsky AS, Yoder BA 2001 Lung injury in neonates: causes, strategies for prevention, and long-term consequences. J Pediatr 139: 478–486

Ramnath VR, Hess DR, Thompson BT 2006 Conventional mechanical ventilation in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distess syndrome. Clin Chest Med 27: 601–613

Carlo WA, Prince LS, St. John EB, Ambalavanan N 2004 Care of very low birth weight infants with respiratory distress syndrome: an evidence-based review. Minerva Pediatr 56: 373–380

Ricard JD, Dreyfuss D, Saumon G 2003 Ventilator-induced lung injury. Eur Respir J Suppl 42: 2s–9s

Zwischenberger JB, Nguyen TT, Upp JR Jr, Bush PE, Cox CS Jr, Delosh T 1994 Complications of neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: collective experience from the extracorporeal life support organization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 107: 838–849

Gattinoni L, Pesenti A, Mascheroni D, Marcolin R, Fumagalli R, Rossi F, Agostoni A 1986 Low-frequency positive-pressure ventilation with extracorporeal CO2 removal in severe acute respiratory failure. JAMA 256: 881–886

Flörchinger B, Philipp A, Klose A, Hilker M, Kobuch R, Rupprecht L, Keyser A, Pühler T, Hirt S, Wiebe K, Müller T, Langgartner J, Lehle K, Schmid C 2008 Pumpless extracorporeal lung assist: a 10-year institutional experience. Ann Thorac Surg 86: 410–417

Zwischenberger JB, Wang D, Lick SD, Deyo DM, Alpard SK, Chambers SD 2002 The paracorporeal artificial lung improves 5-day outcomes from lethal smoke/burn-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome in sheep. Ann Thorac Surg 74: 1011–1016; discussion 1017–1018.

Ambalavanan N, Bulger A, Ware J, Philips J 2001 Hemodynamic effects of levcromakalin in neonatal porcine pulmonary hypertension. Biol Neonate 80: 74–80

Simma B, Luz G, Trawoger R, Hormann C, Klima G, Krecgy R, Baum M 1996 Comparison of different modes of high-frequency ventilation in surfactant-deficient rabbits. Pediatr Pulmonol 22: 263–270

Mrozek JD, Smith KM, Bing DR, Meyers PA, Simonton SC, Connett JE, Mammell MC 1997 Exogenous surfactant and partial liquid ventilation: physiologic and pathologic effects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156: 1058–1065

Muellenbach RM, Kredel M, Said HM, Klosterhalfen B, Zollhoefer B, Wunder C, Redel A, Schmidt M, Roewer N, Brederlau J 2007 High-frequency oscillatory ventilation reduces lung inflammation: a large-animal 24-h model of respiratory distress. Intensive Care Med 33: 1423–1433

Hilgendorff A, Aslan E, Schaible T, Gortner L, Baehner T, Ebsen M, Kreuder J, Ruppert C, Guenther A, Reiss I 2008 Surfactant replacement and open lung concept-comparison of two treatment strategies in an experimental model of neonatal ARDS. BMC Pulm Med 8: 10

Dreyfuss D, Saumon G 1998 Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 294–323

Verbrugge SJ, Lachmann B, Kesecioglu J 2007 Lung protective ventilatory strategies in acute lung injury and acute respiratory distress syndrome: from experimental findings to clinical application. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 27: 67–90

Ranieri VM, Mascia L, Fiore T, Bruno F, Brienza A, Giuliani R 1995 Cardiorespiratory effects of positive end-expiratory pressure during progressive tidal volume reduction (permissive hypercapnia) in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Anesthesiology 83: 710–720

Plotz FB, van Oeveren W, Bartlett RH, Wildevuur CR 1993 Blood activation during neonatal extracorporeal life support. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 105: 823–832

Hirthler MA, Blackwell E, Abbe D, Doe-Chapman R, Le Clair Smith C, Goldthorn J, Canizaro P 1992 Coagulation parameter instability as an early predictor of intracranial hemorrhage during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg 27: 40–43

Stallion A, Cofer BR, Rafferly JA, Ziegler MM, Ryckman FC 1994 The significant relationship between platelet count and haemorrhagic complications on ECMO. Perfusion 9: 265–269

Fazzalari FL, Montoya JP, Bonnell MR, Bliss DW, Hirschl RB, Bartlett RH 1994 The development of an implantable artificial lung. ASAIO J 40: M728–M731

Lynch WR, Montoya JP, Brant DO, Schreiner RJ, Iannettoni MD, Bartlett RH 2000 Hemodynamic effect of a low-resistance artificial lung in series with the native lungs of sheep. Ann Thorac Surg 69: 351–356

Lick SD, Zwischenberger JB, Alpard SK, Witt SA, Deyo DM, Merz SI 2001 Development of an ambulatory artificial lung in an ovine survival model. ASAIO J 47: 486–491

Lick SD, Zwischenberger JB, Wang D, Deyo DM, Alpard SK, Chambers SD 2001 Improved right heart function with a compliant inflow artificial lung in series with the pulmonary circulation. Ann Thorac Surg 72: 899–904

Silveira KS, Boechem NT, do Nascimento SM, Murakami YL, Barboza AP, Melo PA, Castro P, de Moraes VL, Rocco PR, Zin WA 2004 Pulmonary mechanics and lung histology in acute lung injury induced by Bothrops jararaca venom. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 139: 167–177

Maeda Y, Fujino Y, Uchiyama A, Matsuura N, Mashimo T, Nishimura M 2004 Effects of peak inspiratory flow on development of ventilator-induced lung injury in rabbits. Anesthesiology 101: 722–728

Mandava S, Kolobow T, Vitale G, Foti G, Aprigliano M, Jones M, Muller E 2003 Lethal systemic capillary leak syndrome associated with severe ventilator-induced lung injury: an experimental study. Crit Care Med 31: 885–892

The Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network 2000 Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 342: 1301–1308

Kaisers U, Busch T, Wolf S, Lohbrunner H, Wilkens K, Hocher B, Boemke W 2000 Inhaled endothelin A antagonist improves arterial oxygenation in experimental acute lung injury. Intensive Care Med 26: 1334–1342

Zwischenberger JB, Alpard SK, Tao W, Deyo DJ, Bidani A 2001 Percutaneous extracorporeal arteriovenous dioxide removal improves survival in respiratory distress syndrome: a prospective randomized outcomes study in adult sheep. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 121: 542–551

Brunston RL Jr, Tao W, Bidani A, Traber DL, Zwischenberger JB 1997 Organ blood flow during arterio-venous carbon dioxide removal. ASAIO J 43: M821–M824

Bone RC, Maunder R, Slotman G, Silverman H, Hyers TM, Kerstein MD, Ursprung JJ 1989 An early test of survival in patients with the adult respiratory distress syndrome. The PaO2/FiO2 ratio and its differential response to conventional therapy. Prostaglandin E1 Study group. Chest 96: 849–851

Germann PG, Häfner D 1998 A rat model of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), Part 1: Time dependency of histological and pathological changes. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods 40: 101–107

Jobe AH, Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Newnham JP, Ikegami M 2002 Decreased indicators of lung injury with continuous positive expiratory pressure in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res 52: 387–392

Hillman NH, Moss TJ, Kallapur SG, Bachurski C, Pillow JJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Jobe AH 2007 Brief, large tidal volume ventilation initiates lung injury and a systemic response in fetal sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 575–581

Lampland AL, Meyers PA, Worwa CT, Swanson EC, Mammel MC 2008 Gas exchange and lung inflammation using nasal intermittent positive-pressure ventilation versus synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation in piglets with saline lavage-induced lung injury: an observational study. Crit Care Med 36: 183–187

Nold JL, Meyers PA, Worwa CT, Goertz RH, Huseby K, Schauer G, Mammel MC 2007 Surfactant administration in piglets treated with bubble nasal continuous positive airway pressure or synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation: physiology and injury. Neonatology 92: 19–25

Hoegl S, Boost KA, Flondor M, Scheiermann P, Muhl H, Pfeilschifter J, Zwissler B, Hofstetter C 2008 Short-term exposure to high-pressure ventilation leads to pulmonary biotrauma and systemic inflammation in the rat. Int J Mol Med 21: 513–519

Van Kaam AH, de Jaeqere A, Haitsma JJ, Van Aalderen WM, Kok JH, Lachmann B 2003 Positive pressure ventilation with the open lung concept optimizes gas exchange and reduces ventilator-induced lung injury in newborn piglets. Pediatr Res 53: 245–253

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Supported, in part, by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association (PHA 0526041H) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K08 HD046513).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

El-Ferzli, G., Philips, J., Bulger, A. et al. A Pumpless Lung Assist Device Reduces Mechanical Ventilation-Induced Lung Injury in Juvenile Piglets. Pediatr Res 66, 671–676 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181bbbf7a

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181bbbf7a