Abstract

To investigate the relationship among alcohol dehydrogenase-2 (ADH2) and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) genetic polymorphisms, alcohol consumption and the susceptibility to esophageal cancer in a Chinese population, we conducted a case–control study with 221 cases and 191 population-based controls in the Taixing city of Jiangsu Province of China. ADH2 and ALDH2 genotypes were examined using PCR and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography. Alcohol drinkers with the ALDH2 A allele showed a significantly increased risk of esophageal cancer compared with drinkers with the ALDH2 G/G genotype (odds ratio (OR)=3.08, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.65–5.78) or nondrinkers with any genotype (OR=3.05, 95% CI: 1.49–6.25). Drinkers with the ALDH2 A allele and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) were at a significantly higher risk of developing esophageal cancer (OR=11.93, 95% CI: 3.17–44.90) compared with individuals with ALDH2 G/G genotypes and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption <2.5 (kg * years). A dose-dependent positive result was found between cumulative amount of alcohol consumption and risk of esophageal cancer in individuals carrying the ALDH2 A allele (P=0.023) and the homozygous ALDH2 G allele (P=0.047). Compared with individuals carrying both ALDH2 G/G and ADH2 A/A alleles and with a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption <2.5 (kg * years), drinkers carrying both ALDH2 A and ADH2 G alleles and with a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) showed a significantly elevated risk of esophageal cancer (OR=53.15, 95% CI: 4.24–666.84). This result suggests that to help lower their risk for esophageal cancer, persons carrying the ALDH2 A allele should be encouraged to reduce their consumption of alcoholic beverages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Epidemiological studies have consistently shown that alcohol drinking is a risk factor for esophageal cancer.1 When ethanol is consumed, it is metabolized primarily by alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) into acetaldehyde, an intermediate metabolite, and then it is metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) into acetic acid.2 Acetaldehyde, a well-known carcinogen in animals, has an important role in alcohol toxicity in humans.3 Most studies, conducted mainly in Japan, have revealed associations between the ADH2 or ALDH2 polymorphism and esophageal cancer risk.4, 5, 6, 7, 8 Chao et al.9 found that Chinese alcoholic patients with the ADH2 G and ALDH2 A alleles were more susceptible to esophageal cancer. Wu et al.10 also found a multiplicative effect of lifetime alcoholic consumption and genotypes (ADH2 and ALDH2) on esophageal cancer risk, but those were only found in Taiwanese males.

Taixing City, located in the middle part of Jiangsu Province, China, has relatively high incidence and mortality rates for esophageal cancer (in 2005, the age-adjusted mortality rate was 53.66 per 100 000 for esophageal cancer). Our previous study showed that drinking was associated with increased esophageal cancer in this area.11 We also showed no statistical association between ALDH2 and esophageal cancer susceptibility.12 In this study, we increased the sample size to further evaluate the interaction of ADH2 and ALDH2 with lifetime alcohol consumption and study the relationship of the interaction to esophageal cancer risk in Chinese population.

Materials and methods

Subjects

We recruited patients who were histopathologically diagnosed as having esophageal carcinoma from January 2005 to December 2006. Population-based controls were recruited from healthy residents in the villages or towns in which the patients resided. All study subjects completed a questionnaire administrated by a trained interviewer, covering residential, occupational, social, living style, psychological and economical factors; information regarding alcohol consumption included whether the subject had been an alcoholic in his lifetime, what year the subject started and quit, the duration of consumption and the daily amount consumed, and the type of alcoholic beverage consumed. The interviewer then collected blood samples from subjects from a peripheral vein after obtaining their oral informed consent. The collected blood samples were shipped to the public health center within a day. Buffy coat was then separated and stored at −30 °C. A few patients and residents refused to participate in our study, but the overall response rate was 97% for patients and 95% for controls. The Ethics Committee of Jiangsu Provincial Institute of Cancer Research approved this study. Associations could not be assessed in women because of sparse drinking habits.

DNA extraction and genotyping

Whole blood was collected into EDTA-coated tubes and centrifuged for 15 min. The buffy coat layer was isolated. Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 μl of buffy coat using a Qiagen QIAamp DNA blood mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). Genotyping of ADH2 and ALDH2 was determined by PCR and denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography.13 There were three genotypes, namely, G/G, G/A and A/A, for ADH2 Arg47His(rs1229984) and ALDH2 Glu487Lys(rs671, ss676), respectively.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using the SAS (version 6.02) and Epi-info (version 6.04) statistical package. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were adjusted by unconditional logistic regression analysis. The Mantel–Haenszel χ2-method was used to test for significant associations between the ADH2 or ALDH2 genotype and cancer risk. We defined a drinker as a person who drinks at least once a week (absolute ethanol intake more than 40 g) and continuously drinks at least half a year. Lifetime consumption of alcoholic beverage was calculated by multiplying the concentration of alcohol in the consumed beverage by the amount consumed in a day by the number of years consumed, resulting in a number (cumulative amounts of alcohol consumption) designated as kilogram (kg) * year. One ‘kg * year’ was defined as drinking absolute ethanol one kg per day and continuously drinking for 1 year.

Results

In all, 221 cases with esophageal cancer and 191 controls enrolled in this study (Table 1). The proportional distributions of age, occupation, education, smoking and drinking did not significantly differ between cases and controls, but the proportional distributions of income (10 years before and recent years) were significantly lower in cases than in controls (4.52 and 3.64 for t-value, P<0.01).

As shown in Table 2, the distribution of the ALDH2 genotypes was significantly different between controls and cases (χ2=22.30, P<0.01). The frequency of ADH2 A/A, A/G and G/G genotypes demonstrated no significant differences between cases and controls (χ2=4.92, P=0.085). The allelic distribution of ADH2 and ALDH2 polymorphisms was in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (P>0.05). As for income-adjusted odds ratio, compared with ALDH2 G/G carriers, the OR was 1.70 for G/A carriers, 5.69 for A/A carriers and 2.19 for the two genotypes combined.

As shown in Table 3, alcohol drinkers with the ALDH2 A allele showed a significantly increased risk of esophageal cancer compared with drinkers with the ALDH2 G/G genotype (OR=3.08, 95% CI: 1.65–5.78) or nondrinkers (OR=3.05, 95% CI: 1.49–6.25). We examined the relationship between ALDH2 genotypes and esophageal cancer according to drinking status (Table 3). The results are shown as follows:

Compared with drinkers with the ALDH2 G/G genotype, drinkers carrying the ALDH2 A allele had a significantly elevated risk of esophageal cancer, regardless of the age at which they started drinking, the duration, frequency and amount of alcohol consumption. ORs were particularly high among those with alcohol consumption >60 g every time (OR=21.72) and among those with a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption >2.5 kg * years (OR=21.84).

In addition, compared with individuals possessing ALDH2 G/G genotypes and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption <2.5 (kg*years), drinkers with the ALDH2 A allele and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) were at a significantly higher risk of developing esophageal cancer (OR=11.93, 95% CI: 3.17–44.90).

We also noted a 6.13-fold higher risk among ALDH2 A allele carriers if the amount of alcohol consumption every time was greater than 60 g, and a 5.99-fold higher risk if the cumulative amount of alcohol consumption was greater than 2.5 kg * years.

As for the relationship between the ADH2 genotype, drinking habit and esophageal cancer risk, our results demonstrated that drinking status was not a risk modifier among people with the same genotype, nor was genotype among people with the same drinking status. The only exceptions were ADH2 G allele carriers who started drinking before the age of 25 years, who had a 2.39-fold higher risk than those who started drinking after 25 years (Table 4).

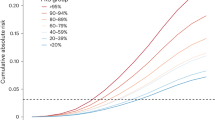

A dose-dependent relationship was observed between cumulative amount of alcohol consumption and the risk of esophageal cancer in all individuals (P=0.023 in ALDH2 A allele carriers; P=0.047 in ALDH2 G/G homozygotes). However, the trend was not significant if the subjects were grouped by their ADH2 genotypes (data not shown). Among ALDH2 A allele carriers, drinkers with a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) had a 6.58-fold higher risk of esophageal cancer than nondrinkers (Table 5).

We next investigated the combination of ALDH2 and ADH2 genotypes. Compared with individuals with both ALDH2 G/G and ADH2 A/A genotypes, whose cumulative amount of alcohol consumption was less than 2.5 kg * years, drinkers carrying the ALDH2 A allele showed an elevated risk of esophageal cancer regardless of their cumulative amount of alcohol consumption or ADH2 genotypes, and ALDH2 A and ADH2 G allele carriers with a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) showed the highest elevated risk of esophageal cancer (OR=53.15, 95% CI: 4.24–666.84) (Table 6).

Discussion

Esophageal cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors in human beings. China is the country with the highest incidence and mortality rate of esophageal cancer. Poor economic conditions can increase the risk of esophageal cancer risk. In this study, we found that the proportional distributions of income were significantly lower in cases than in controls. It indicated that lower income is the risk factor for esophageal cancer in this population. As in many other multietiology diseases, both environmental exposure and genetic factors may have a role in the development of esophageal cancer. Many environmental carcinogens are procarcinogens that need to be activated to act as ultimate carcinogens before carcinogenesis is initiated. Some metabolic enzymes are closely related to the activation and detoxification of procarcinogens. Individual susceptibility to cancer may be associated with the genetic polymorphism of certain enzymes that metabolite these procarcinogens. Acetaldehyde, the oxidative metabolite of ethanol, is recognized to be carcinogenic in animals and suspected to have similar effects on human beings.14 Ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde and then to acetate by ADH and ALDH, respectively, both of which have genetic polymorphisms. It has been generally recognized that both environmental exposures/lifestyle and genetic makeup influence the genetic susceptibility to cancer. In studies on cancer risk from alcohol exposure, it is necessary to investigate not only alcohol metabolism, which is mainly decided by the genetic variations of ADH and ALDH, but also drinking habits. Thus, investigation of ADH and ALDH polymorphisms combined with alcohol consumption will benefit many people by identifying their risk for esophageal cancer. Up to this date, there are only two papers addressing the relationship between ADH2 and ALDH2 genetic polymorphisms and esophageal cancer susceptibility in the mainland of China.15, 16 In both studies, the association of ADH2/ALDH2 with esophageal cancer development was found. However, none of these studies reported the combined effects of alcohol metabolic enzyme polymorphisms and drinking habits, especially cumulative amount of alcohol consumption.

In this study, we examined the associations of esophageal cancer with ALDH2 and ADH2 genetic polymorphisms, in conjunction with alcohol drinking habits. A dose-dependent positive result was found between cumulative amount of alcohol consumption and the risk of esophageal cancer in individuals carrying the ALDH2 A allele (χtrend2=5.19, P=0.023) and those with homozygous G alleles (χtrend2=3.92, P=0.047). It was consistent with our previous reports that demonstrated a positive correlation between individuals carrying the ALDH2 A allele and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption in the development of primary hepatocellular carcinoma.17 In addition, the OR of ALDH2 A allele carriers with cumulative amounts of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) was 5.99-fold higher than that of individuals with the same ALDH2 status but who had cumulative amounts of alcohol consumption <2.5 (kg * years), 11.93-fold higher than that of individuals with the ALDH2 G/G genotype and cumulative amounts of alcohol consumption <2.5 (kg * years), and 21.84-fold higher than that of drinkers with a ALDH2 G/G genotype and cumulative amounts of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years). These results demonstrated that ALDH2 polymorphisms had a significant interaction with heavy alcohol consumption in the development of esophageal cancer, and that the ALDH2 A allele might be a risk modifier of esophageal cancer for those consuming large amounts of alcohol.

Previous studies have shown that it is not the ADH2 genotypes but the ALDH2 genotypes that determined an individual's peak blood acetaldehyde concentration.18, 19 ALDH2 generates acetic acid from acetaldehyde metabolism and the ALDH2 variant genotypes lack this enzyme activity. Therefore, long durations and large amounts of alcohol consumption will increase the concentration of acetaldehyde in the ALDH2 A allele. Some studies found that after drinking, blood acetaldehyde concentrations in those with ALDH2 A/A and G/A were 19- and sixfold higher than in those with the G/G genotype, respectively.20 Our findings were similar with previous studies that showed that the accumulation of acetaldehyde in the body could increase the risk of esophageal cancer when the acetaldehyde concentration reached a certain level.10

Our previous study showed that compared with drinkers with ALDH2 G/G and ADH2 G/G genotypes and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩽3 (kg * years), drinkers with the ALDH2 A and ADH2 A alleles and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption >3 (kg * years) were at an increased risk for primary hepatocellular carcinoma (adjusted OR=4.26, 95% CI: 0.63–29.08), but this observation did not reach statistical significance.17 In this study, we, for the first time, report that compared with individuals carrying both ALDH2 G/G and ADH2 A/A genotypes with a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption <2.5 (kg * years), drinkers with ALDH2 A and ADH2 G alleles and a cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5(kg * years) showed a significantly elevated risk of developing esophageal cancer (OR=53.15, 95% CI: 4.24–666.84). This result is in line with a former study in Taiwanese men.10 Thus, it seems that the interaction mechanism of alcohol metabolic enzyme polymorphisms and alcohol drinking on esophageal cancer risk is different from that on HCC risk. Our results suggested that, as drinking can be an activity that lasts for a very long time, consuming a high amount of alcohol could lead to the development of esophageal cancer at the end of this long process. The cumulative amount of alcohol consumption ⩾2.5 (kg * years) may be considered as a threshold of significant increase in individuals carrying both ALDH A and ADH2 G alleles, who we consider to be at high risk. Thus, they should be encouraged to reduce their consumption of alcoholic beverages in order to lower their esophageal cancer risk.

References

Gemma, S., Vichi, S. & Testai, E. Individual susceptibility and alcohol effects:biochemical and genetic aspects. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita. 42, 8–16 (2006).

Bosron, W. F. & Li, T. K. Genetic polymorphism of human liver alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases, and their relationship to alcohol metabolism and alcoholism. Hepatology 6, 502–510 (1986).

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Allyl compounds, aldehydes, epoxides and peroxides. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinoge. Risk. Chemi. Hum. 36, 101–132 (1985).

Yokoyama, A., Muramatsu, T., Ohmori, T., Higuchi, S., Hayashida, M. & Ishii, H. Esophageal cancer and aldehyde dehydrogenase22 genotypes in Japanese males. Cancer. Epidemiol. Biomarkers. Prev. 5, 99–102 (1996).

Yokoyama, A., Muramatsu, T., Ohmori, T., Yokoyama, T., Okuyama, K., Takahashi, H. et al. Alcohol-related cancers and aldehyde dehydrogenase22 in Japanese alcoholics. Carcinogenesis 19, 1383–1387 (1998).

Hori, H., Kawano, T., Endo, M. & Yuasa, Y. Genetic polymorphisms of tobacco and alcohol-related metabolizing enzymes and human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma susceptibility. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 25, 568–575 (1997).

Matsuo, K., Hamajima, N., Shinoda, M., Hatooka, S., Inoue, M., Takezaki, T. et al. Gene–environment interaction between an aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) polymorphism and alcohol consumption for the risk of esophageal cancer. Carcinogenesis 22, 913–916 (2001).

Yang, C. X., Matsuo, K., Ito, H., Hirose, K., Wakai, K., Saito, T. et al. Esophageal cancer risk by ALDH2 and ADH2 polymorphisms and alcohol consumption: exploration of gene-environment and gene–gene interactions. Asian Pac. J. Cancer. Prev. 6, 256–262 (2005).

Chao, Y. C., Wang, L. S., Hsieh, T. Y., Chu, C. W., Chang, F. Y. & Chu, H. C. Chinese alcoholic patients with esophageal cancer are genetically different from alcoholics with acute pancreatitis and liver cirrhosis. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 95, 2958–2964 (2000).

Wu, C. F., Wu, D. C., Hsu, H. K., Kao, E. L., Lee, J. M., Lin, C. C. et al. Relationship between genetic polymorphisms of alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk in males. World J. Gastroenterol. 11, 5103–5108 (2005).

Ding, J. H., Li, S. P., Gao, C. M., Zhou, J. N., Su, P., Wu, J. Z. et al. [On population based case-control study of upper digestive tract cancer]. China Public Health 17, 319–320 (2001).

Ding, J. H., Wu, J. Z., Li, S. P., Gao, C. M., Zhou, J. N., Su, P. et al. Polymorphisms of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotypes and alcohol consumption for the susceptibility of liver cancer, stomach cancer and esophageal cancer. Bulletin of Chinese Cancer 11, 450–452 (2002).

Gao, C. M., Takezaki, T., Wu, J. Z., Zhang, X. M., Cao, H. X., Ding, J. H. et al. Polymorphisms of alcohol dehydrogenase 2 and aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 and colorectal cancer risk in Chinese males. World J. Gastroenterol. 14, 5078–5083 (2008).

Matsuo, K., Hamajima, N., Shinoda, M., Hatooka, S., Inoue, M., Takezaki, T. et al. Gene–environment interaction between an aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 (ALDH2) polymorphism and alcohol consumption for the risk of esophageal cancer. Carcinogenesis 22, 913–916 (2001).

Yang, S. J., Wang, H. Y., Li, X. Q., Du, H. Z., Zheng, C. J. & Chen, H. G. Genetic polymorphisms of ADH2 and ALDH2 association with esophageal cancer risk in southwest China. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 5760–5764 (2007).

Guo, Y. M., Wang, Q., Liu, Y. Z., Chen, H. M., Qi, Z. & Guo, Q. H. Genetic polymorphisms in cytochrome P4502E1, alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases and the risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Gansu Chinese males. World J. Gastroenterol. 14, 1444–1449 (2008).

Ding, J., Li, S., Wu, J., Gao, C., Zhou, J., Cao, H. et al. Alcohol dehydrogenase-2 and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotypes, alcohol drinking and the risk of primary hepatocellular carcinoma in a Chinese population. Asian Pac. J. Cancer. Prev. 9, 31–35 (2008).

Crabb, D. W., Edenberg, H. J., Bosron, W. F. & Li, T. K. Genotypes for aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency and alcohol sensitivity: the inactive ALDH2*2 allele is dominant. J. Clin. Invest. 83, 314–316 (1989).

Yoshihara, E., Ameno, K., Nakamura, K., Ameno, M., Itoh, S., Ijiri, I. et al. The effects of the ALDH2*1/*2, CYP2E1 C1/C2 and C/D genotypes on blood ethanol elimination. Drug. Chem. Toxicol. 23, 371–379 (2000).

Mizoi, Y., Yamamoto, K., Ueno, Y., Fukunaga, T. & Harada, S. Involvement of genetic polymorphism of alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenases in individual variation of alcohol metabolism. Alcohol. Alcohol. 29, 707–710 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a grant from the Department of Health (H200526), Jiangsu Province, PR China. We thank the local staffs of the Public Health Center of Taixing City for their assistance in data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ding, Jh., Li, Sp., Cao, Hx. et al. Alcohol dehydrogenase-2 and aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 genotypes, alcohol drinking and the risk for esophageal cancer in a Chinese population. J Hum Genet 55, 97–102 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2009.129

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/jhg.2009.129

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Factors associated with the high prevalence of oesophageal cancer in Western Kenya: a review

Infectious Agents and Cancer (2017)

-

Association between alcohol dehydrogenase-2 gene polymorphism and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2016)

-

Gene–environment interactions on the risk of esophageal cancer among Asian populations with the G48A polymorphism in the alcohol dehydrogenase-2 gene: a meta-analysis

Tumor Biology (2014)

-

ADH1B is associated with alcohol dependence and alcohol consumption in populations of European and African ancestry

Molecular Psychiatry (2012)