Abstract

Purpose: Family history guides cancer prevention and genetic testing. We sought to estimate the population prevalence of increased familial risk for breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, and colorectal cancers and hereditary cancer syndromes that include these cancers.

Methods: Using the 2005 California Health Interview Survey data, a weak, moderate, or strong familial cancer risk was assigned to 33,187 respondents. Guidelines were applied to identify individuals with hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer.

Results: Among respondents without a personal history of cancer, familial breast cancer was most prevalent; 7% had a moderate and 5% a strong familial risk. Older individuals and women were more likely to report family history of cancer. Generally, whites had the highest prevalence, and Asians and Latinos had the lowest prevalence. Among women without a personal history of breast or ovarian cancer, 2.5% met criteria for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer, and among individuals without a personal history of colorectal, endometrial or ovarian cancer, 1.1% met criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer.

Conclusions: We provide population-based prevalence estimates for moderate and strong familial risk for five common cancers and hereditary breast-ovarian cancer and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer. Such estimates are helpful in planning and evaluation of genetic services and prevention programs, and assessment of cancer surveillance and prevention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Family history risk assessment is important in guiding screening and prevention strategies for many common cancers,1–3 including referral for genetic consultation and testing.4,5 A positive family history can increase an individual's risk of cancer from 2 to 5 times, and this risk generally increases with an increasing number of affected relatives and earlier ages of cancer onset.6 Additional characteristics of high-risk family histories include occurrence of multifocal or bilateral cancers, cancer in the less often affected sex (e.g., male breast cancer), and related cancer diagnoses in a pattern suggestive of a hereditary syndrome.6

By recognizing the magnitude of risk associated with these family history characteristics, stratification of familial risk into different groups is possible.6,7 For people with increased familial cancer risk, preventive interventions can include recommendations for lifestyle changes; more aggressive screening for early cancer detection beginning at younger ages, occurring at more frequent intervals and with more intensive methods than used for average risk individuals; use of chemoprevention; and for those at highest risk, prophylactic surgeries.8,9

The only population prevalence estimates for individuals with a family history of cancer are available from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).10 The NHIS assessed prevalence of individuals with one or more first-degree relatives with breast, colorectal, lung, prostate, and ovarian cancer. However, the NHIS did not ascertain information about cancer in second-degree relatives, and the NHIS data analysis did not consider age at diagnosis or combinations of cancer diagnoses; all of which are necessary for familial risk stratification and recognition of hereditary cancer syndromes. Furthermore, the NHIS analysis did not consider prevalence rates according to personal history of cancer. Thus, population prevalence rates of individuals at risk for cancer who have moderate or strong familial risk or hereditary forms of cancer are not available. Such estimates are necessary for planning and evaluation of genetic services and prevention programs and for assessment of cancer surveillance and prevention strategies.

Using family history data from the 2005 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), which collected information about breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, and colorectal cancers and age at cancer diagnosis for first- and second-degree relatives, we sought to estimate the population prevalence of weak, moderate, and strong familial risk for these cancers and the prevalence of hereditary cancer syndromes that include these cancers among at-risk individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We used data from respondents to the 2005 CHIS Adult Questionnaire, aged 18–64 years. CHIS is designed to yield reliable estimates for large and medium-sized counties statewide, representing California's major ethnic groups and several ethnic subgroups. CHIS fulfills these goals by obtaining a large sample using a stratified sample design. A random-digit dial computer-assisted telephone survey of households drawn from every county in the state is administered in English, Spanish, Chinese, Korean, and Vietnamese. Only one adult from each household is interviewed; thus, it is highly unlikely that adult CHIS respondents are related to each other.

We received approval from the CHIS Data Disclosure Review Committee to use the CHIS 2005 variables necessary to conduct our research, and we received approval from the RAND Corporation's Human Subjects Protection Committee to analyze the data. Available demographic data included age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, educational level, and annual income level. Clinical data included personal history of cancer. Family history data included information regarding breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, and colorectal cancer in first- and second-degree maternal or paternal relatives, including information about early-onset (before the age of 50 years) or late-onset (at or after the age of 50 years) cancer. We have chosen these thresholds for early- and late-onset cancer based on published guidelines.4,11–13

Familial risk stratification

For each individual, a weak, moderate, or strong familial risk was assigned for each cancer type. Assignment to the familial risk groups was based on rules derived from empirical data, and when such data were unavailable, general principles of familial risk assessment were followed that consider degree of relationship of affected relatives, maternal or paternal lineage, and their age at cancer diagnosis.6 The rules for familial risk stratification for each of the five cancer types considered the presence or absence of each respective cancer and associated cancers diagnosed before the age of 50 years or at the age of 50 years and older in all first- and second-degree relatives. For familial risk of breast and ovarian cancer, both breast and ovarian cancer in relatives were considered. For colon cancer, both colon and endometrial cancer in relatives were considered. For prostate cancer, only prostate cancer in relatives was considered, and for endometrial cancer, only endometrial cancer in relatives was considered. A weak risk was assigned if there was no family history, if there was late-onset cancer in only one second-degree relative from one or both sides of the family, or a first-degree relative with an associated cancer (e.g., endometrial cancer in a mother corresponding to weak familial risk of colorectal cancer). Moderate risk was generally assigned if there was only one first-degree relative with late-onset cancer, two second-degree relatives from the same lineage with late-onset cancer, or one second-degree relative with early-onset cancer and other second-degree relatives with an associated cancer (e.g., one second-degree relative with ovarian cancer and another from the same lineage with late-onset breast cancer corresponding to a moderate familial risk of ovarian cancer). Strong familial risk was generally assigned if there was a first-degree relative with early-onset cancer, when multiple relatives were affected, or when a hereditary syndrome was suspected (see later). Case-control studies have shown that for most cancers, a moderate familial risk is associated with about a 2-fold increase in risk, and a strong familial risk is associated with about a 3-fold or greater increase compared with a weak familial risk.6

“Don't know” or missing responses (refusals or not ascertained) to questions about a cancer history were counted as “no” responses, and when relating to age at diagnosis, these responses were counted as late-onset disease. Thus, all responses were considered, and our approach to coding assured that any biases introduced would favor underestimation of prevalence and familial risk. There were 499 (1.3%) “don't know” responses, seven (0.03%) “refused,” and one (0.0003%) “not ascertained” response to the stem question of “Have any of your female relatives (grandmothers, aunts, mother, sisters, daughters) ever had breast, ovarian, uterine or colon cancer?” In response to the other stem question, “Have any of your male relatives (grandfathers, uncles, father, brothers, sons) ever had prostate, colon or breast cancer?” there were 508 (1.4%) “don't know” responses, 13 (0.03%) “refused,” and one (0.0003%) “not ascertained” response. The numbers of “don't know” and missing responses in subsequent questions asking about the type of relative having a specific cancer and whether it was before the age of 50 years were similar or even less frequent.

Hereditary cancer syndrome definitions

We focused on two relatively common hereditary cancer syndromes: hereditary breast-ovarian cancer (HBOC) and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC), also known as Lynch syndrome. For both syndromes, guidelines are available regarding family history criteria for genetic testing and early cancer detection and prevention interventions.3–5,11–13 The family history rules we developed for HBOC and HNPCC were derived from the family history criteria found in these guidelines (Fig. 1).4,11–13 However, certain criteria could not be applied because the necessary data were not collected. For example, for HBOC, family history of bilateral breast cancer and Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry were not available, and for HNPCC, only family histories of colorectal and endometrial cancers were considered. Thus, it is possible that some individuals meeting HBOC and HNPCC criteria were missed.

Family history criteria for hereditary cancer syndromes applied to CHIS 2005 data. Our family history criteria for HBOC were adapted from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force criteria4; however, we could not assess a history of a first-degree relative with bilateral breast cancer or the criteria specific for Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry. Our family history criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) were adapted from the Amsterdam II criteria11 and revised Bethesda guidelines.12,13 The revised Bethesda criteria are used to determine which individuals with colon cancer should undergo testing of their tumor for microsatellite instability. An adaptation of these criteria was used to identify family histories that suggested the possible diagnosis of HNPCC. We assessed family history of colorectal and endometrial cancer. We did not assess family history of other HNPCC-associated cancers that could fulfill the Amsterdam II criteria (small bowel, ureter, and renal pelvis cancers) or the revised Bethesda guidelines (gastric, ovarian, pancreas, ureter, renal pelvis, biliary tract, small bowel and brain tumors, sebaceous gland adenomas, and keratoacanthomas). In addition, we could not satisfy two Amersterdam II criteria including the exclusion of familial adenomatous polyposis as a diagnosis or verification of the cancer history by pathologic examination, and we could not satisfy the revised Bethesda guidelines addressing histology of colorectal cancer or the history of synchronous colorectal cancer.

Statistical analyses

Basic descriptive analyses of the distribution of demographic and family history characteristics among respondents with and without cancer were performed. Prevalence rates for moderate and strong familial risk are reported for at-risk individuals lacking a personal history of breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, or colorectal cancer. These prevalence rates are not reported for individuals with a personal history of these cancers because of small numbers of individuals within subgroups according to age, sex, or ethnicity/race. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to determine which demographic factors are significantly associated with increased familial risk (P value <0.05 for Wald F statistic) and to assess associations between personal and family history of cancers adjusting for the demographic variables. To account for the complex survey sample design, all analyses were conducted with SUDAAN 10.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute, January 2010) using replicate weight jackknife variance estimation.

RESULTS

There were 33,187 CHIS respondents between the age of 18 and 64 years, with 786 reporting a personal history of female breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, or colorectal cancer. There were no reports of personal history of male breast cancer. Characteristics of the respondents are provided in Table 1. Those with cancer were more often older and female, and almost half were women with a personal history of breast cancer. Among all respondents, 14.4% were assigned a moderate familial risk and 7.8% a strong familial risk for at least one of the five cancers of interest.

Table 2 lists the prevalence rates for moderate and strong familial risk for each cancer type in respondents without a personal history of breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, or colorectal cancer. Family history of breast cancer was most frequent with prevalence estimates of 6.7% for moderate familial risk and 5.0% for strong familial risk. Family history of ovarian cancer was least frequent with prevalence estimates of 1.6% and 1.0% for moderate and strong familial risk, respectively. For the other cancers, the prevalence of individuals with strong familial risk was about 1%, and the prevalence of moderate familial risk ranged from 1.8% to 4.5%. The ratio of moderate to strong familial risk prevalence was greatest for colorectal and prostate cancer, with values of about 4–6, respectively, whereas the corresponding ratios for breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer were 1.3–1.6.

The significance of different demographic factors varied in association with increased familial risk for the different cancer types. Age was significant for breast, colorectal, prostate (P < 0.0001), and endometrial (P = 0.004) cancer but not ovarian cancer. Sex was significant for all cancers (P < 0.0001) except prostate cancer. Race/ethnicity was only significant for increased familial risk of prostate (P = 0.006) and colorectal (P = 0.007) cancer. Educational level was significantly associated with increased familial risk of breast (P < 0.0001), prostate (P = 0.0001), and colorectal (P = 0.0005) cancer. Marital status was only significant for increased endometrial cancer risk (P = 0.003). Annual income was only significantly associated with increased familial risk of ovarian (P = 0.03) and prostate (P = 0.007) cancer.

Table 3 lists the prevalence of moderate and strong familial risk for breast, ovarian, endometrial, prostate, and colorectal cancer in respondents without a personal history of these cancers according to age group. Older individuals had higher prevalence estimates of moderate and strong familial risk for each cancer except for ovarian cancer, where the prevalence for strong and moderate familial risk was the same in older and younger individuals. Except for ovarian cancer, older individuals reported strong familial risk for cancer 1.3–2.0 times more frequently than younger individuals, and for each cancer type, older individuals reported moderate familial risk 1.3–2.2 times more frequently than younger individuals.

Prevalence of moderate and strong familial risk for each cancer type reported by women and men is shown in Table 4. Women had higher prevalence estimates of both moderate and strong familial risk for each type of cancer except prostate cancer, where the prevalence estimates for both familial risk groups were similar for both sexes. Women reported moderate or strong familial risk for breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancer about 1.4 times more frequently than men. The greatest difference in prevalence of increased familial risk between women and men was observed for endometrial cancer, for which women were about 2.5 times more likely to report a moderate or strong familial risk than men.

Prevalence of moderate and strong familial risk according to ethnicity/race is shown in Table 5. Among individuals without a personal history of one of the five cancers of interest, generally whites and African Americans had the highest prevalence estimates of moderate and strong familial risk. Whites had the highest prevalence estimates for strong familial risk of breast, endometrial, and colorectal cancer (6.5%, 1.8%, and 1.3%, respectively), and African Americans had the highest prevalence estimates for strong familial risk of ovarian and prostate cancer (1.4% for each). Asians had the lowest prevalence of strong familial risk for all cancers. Moreover, Asians had the lowest prevalence of moderate familial risk for endometrial and prostate cancer, and Latinos had the lowest prevalence of moderate familial risk for breast, ovarian, and colorectal cancer.

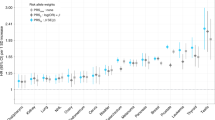

Assessment of the strength of association between increased familial risk and personal history of cancer adjusted for demographic factors and personal history of other cancer is shown in Table 6. For all the cancers, a moderate compared with weak familial risk was associated with about a 2-fold increase in cancer prevalence, ranging from 1.7 to 2.6. However, these associations were only significant for breast and colorectal cancer. For all the cancers, a strong compared with weak familial risk was significantly associated with cancer, and except for breast cancer, the odds ratios were substantially greater than observed for moderate familial risk, ranging from 5.2 to 7.8. In the case of familial risk for breast cancer, we observed similar odds ratios for moderate and strong familial risk.

We found 573 women (2.5%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.2–2.8) without a personal history of breast or ovarian cancer had family history criteria suggestive of HBOC according to the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force guidelines4 (Table 7). Most (94.5%) of the women meeting these criteria were assigned a strong familial risk for breast and/or ovarian cancer, and the remaining 5.5% were assigned a moderate familial risk (Table 7). Among women without a personal history of breast or ovarian cancer who did not meet the family history criteria for HBOC, most (87.7%) were assigned a weak familial risk for breast and/or ovarian cancer; only 3.5% were assigned a strong familial risk and 8.8% a moderate familial risk.

Only 62 individuals (0.2%, 95% CI: 0.1–0.3) without a personal history of colorectal, endometrial, or ovarian cancer had family histories that met adapted Amsterdam II criteria11 (as shown in Fig. 1) consistent with a diagnosis of HNPCC (Table 8). Among those meeting the criteria, 100% were assigned a strong familial risk for colorectal or endometrial cancer. For those who did not meet the adapted Amsterdam II criteria, most (92.0%, 95%CI: 91.6–92.3) had a weak familial risk; only 2.4% (95% CI: 2.3–2.7) had a strong familial risk and 5.6% (95% CI: 5.3–5.9) a moderate familial risk for colorectal or endometrial cancer.

We also adapted criteria from the revised Bethesda guidelines12,13 (as shown in Fig. 1) to identify families with the possible diagnosis of HNPCC (Table 8). There were 467 respondents (1.1%, 95% CI: 0.9–1.2) without a personal history of colorectal, endometrial, or ovarian cancer who had family histories that met these criteria, 91.0% (95% CI: 87.2–93.7) had a strong familial risk for colorectal cancer or endometrial cancer, and 9.0% (95% CI: 6.3–12.8) had a moderate familial risk. Most of the individuals with a moderate familial risk for colorectal or endometrial cancer meeting these criteria had family members with ovarian cancer, which is a cancer included in the revised Bethesda criteria, but it was not included in our assessment of familial risk for colorectal or endometrial cancer. Of those who did not meet the adapted revised Bethesda criteria, 93% (95% CI: 92.6–93.3) had a weak familial risk, 5.6% (95% CI: 5.3–5.9) had a moderate familial risk, and 1.5% (95% CI: 1.3–1.7) had a strong familial risk for colorectal or endometrial cancer.

DISCUSSION

We provide population-based prevalence estimates for moderate and strong familial risk for five common cancers and family histories consistent with HBOC and HNPCC among adults without a personal cancer history, aged 18–64 years. Among all respondents, 14.6% were assigned a moderate familial risk and 7.7% a strong familial risk for at least one of the five cancers of interest. Generally, moderate familial risk was associated with a 2-fold increase in cancer and strong familial risk a 5- to 7-fold increase.

Familial risk stratification into strong or moderate risk groups identified all individuals at risk for the most prevalent cancers associated with HBOC and HNPCC, and a small but important number of individuals with strong and moderate familial risk who did not meet criteria for these syndromes yet may benefit from colorectal and breast cancer screening at an earlier age.1,2

Among at-risk respondents, 2.5% had family histories suggestive of HBOC and, depending on the criteria, 0.2–1.1% had family histories suggestive of HNPCC. The adapted revised Bethesda guidelines were less restrictive than the adapted Amsterdam II criteria, and, as a result, there was a greater number of at-risk individuals with strong or moderate familial risk for colorectal or endometrial cancer meeting these HNPCC criteria. These prevalence estimates for individuals at risk for cancers associated with HBOC and HNPCC will be helpful for planning and evaluation of genetic services and prevention programs and for assessment of cancer surveillance and prevention strategies for breast, ovarian, endometrial, and colorectal cancers.

Our prevalence estimates for moderate and strong familial risk for breast, ovarian, colorectal, and prostate cancer are slightly greater than the prevalence estimates of a positive family history described using the NHIS data, but the trends are similar.10 The higher prevalence estimates with the CHIS 2005 data are probably due to inclusion of family history of cancer in second-degree relatives and combinations of cancer in first- or second-degree relatives associated with hereditary cancer syndromes, whereas NHIS analyses did not include these histories in determining prevalence estimates of family history. In addition, site-specific prompting of cancer in specific family members was used in the CHIS 2005 interviews but not with NHIS. Such site-specific prompting should increase the reporting of cancer in relatives.

Breast cancer was the most prevalent type of familial cancer for both the moderate and strong familial risk groups followed by colorectal and prostate cancer. The proportion of individuals with moderate and strong familial risk depended on the cancer type. Among individuals reporting a positive family history of breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer, we observed similar proportions of individuals with moderate and strong familial risk. However, among those reporting a positive family history of colorectal and prostate cancer, there were greater numbers with a moderate compared with a strong familial risk. Therefore, limiting familial risk assessment to dichotomous assessment that only considers the presence or absence of early-onset cancer in a first-degree relative—which is a common practice—is more likely to underestimate familial risk for colorectal and prostate cancer compared with breast, ovarian, and endometrial cancer.

Similar to the results found with the NHIS data,10 we found that prevalence of a positive family history of cancer was greater among the older respondents, and age was a significant variable associated with increased familial risk for all cancers but ovarian cancer. This is likely because more of the older individuals have family members who have lived long enough to develop these cancers. However, the magnitude of the effect of age also seemed to be dependent on the cancer type. Older individuals were about twice as likely to report a moderate or strong familial risk for colorectal cancer, but for ovarian cancer, the proportion of older and younger individuals with moderate and strong family histories was relatively similar. These results suggest that familial risk stratification is relevant for both younger and older people.

Sex was a significant variable associated with increased familial risk for all cancers except prostate cancer. We found that women were more likely than men to report a family history of cancer, particularly a family history of endometrial cancer. These differences in reporting have been described previously.10 Because specificity of self-reports of cancer family history is high with lower rates of sensitivity,14,15 it seems more likely that men are underreporting their family histories than women overreporting. Moreover, because reports of family history of prostate cancer were similar among men and women, it seems that underreporting by men may be attributable to a perceived lack of relevance of the family history of these cancers for men. The reasons for these reporting differences of cancer family history should be investigated, and public health campaigns targeted at the cause to improve opportunities for family history-based cancer prevention in men and to improve communication about cancer among all family members.

There were modest differences in the prevalence estimates of moderate and strong familial cancer risk between the ethnic/racial groups, and race/ethnicity was only significantly associated with increased familial risk of prostate and colorectal cancer. Some differences in prevalence estimates might be explained by the average age of the groups, with younger ethnic/racial groups (i.e., Asians and Latinos in California) less likely to report cancer in their family because fewer of their relatives have lived long enough to develop these cancers compared with older respondents. Some of the differences in prevalence of moderate and strong familial cancer risk may be explained by differences in cancer prevalence according to race/ethnicity. For example, prostate cancer is most prevalent among African Americans and least prevalent among Asians,16 and not surprisingly African Americans have the highest prevalence of strong familial risk for prostate cancer and Asians the lowest prevalence. Interestingly, we found a significant interaction between race/ethnicity and age associated with increased familial risk of prostate cancer (P = 0.0005) but no other cancers.

We found significant associations between strong compared with weak familial risk and cancer for each of the five cancers we studied, and for female breast cancer and colorectal cancer, we found significant associations between moderate familial risk and cancer. Except for breast cancer, where the magnitude of association was about the same for moderate and strong familial risk, the odds ratios were 2–4 times greater for strong compared with moderate familial risk for the other types of cancer, with odds ratios for strong familial risk ranging from 5.2 to 7.8 and for moderate familial risk ranging from 1.7 to 2.6. These estimates are consistent with reports from the literature.6

In the case of breast cancer, the similar magnitude of association with breast cancer given a strong or moderate familial risk is unexpected and could be attributable to demographic characteristics of the population or survival bias explained by our cross-sectional design. Women with high-risk breast cancer family histories are more likely to develop breast cancer at a younger age, and they are less likely to survive.17 Thus, women with breast cancer and strong familial risk would have been less available for participation in the CHIS 2005 interview resulting in underrepresentation of this group and lower odds ratios for strong familial risk. In contrast, individuals with ovarian and colorectal cancer and a positive family history are more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age, but they have similar or improved survival compared with individuals diagnosed at older ages.18–24 Thus, these differences in age at onset and survival given a strong familial risk may explain the differences we observed in the magnitude of the associations between a strong and weak familial risk for breast cancer versus the other types of cancers. Prospective studies would be helpful to better understand these associations.

The large number and diversity of the CHIS 2005 respondents and the comprehensive personal and family history data they have provided present a unique opportunity. Although California's demographics do not reflect the general U.S. population, CHIS data can provide important information regarding minority ethnic groups that would not be available from most state or national surveys. However, the cross-sectional design prohibits us from establishing any temporal associations concerning family history as a risk factor. In addition, relatively small prevalence rates for personal history of cancer precluded certain subgroup analyses.

Another potential limitation is lack of validation of self-reports of a personal history and family history of cancer. Self-reports of personal cancer history are generally reliable, especially for breast, prostate, and colon cancer.25 Several studies have investigated the validity of family history reports for both first- and second-degree relatives for the cancers under study, and they show reasonably accurate reporting. Most sensitivity values for self-reports of a positive family history of these conditions in a first-degree relative range from 70 to 90%, and specificity is usually 90% or greater.14,15 Accuracy, however, depends on the type of cancer, and it is less for more distant relatives and when historians are older. Therefore, before clinical decisions are based on such information, confirmation of family health histories is advisable.

Family history is an important and prevalent risk factor for common cancers. Recognizing patterns of familial cancer that signify increased risk and possible hereditary syndromes can help to identify individuals who may have the most to gain from preventive interventions including genetic testing.

References

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to clinical preventive services. Cancer. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/cps3dix.htm#cancer. Accessed November 15, 2009.

American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Guidelines for the early detection of cancer. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/PED/content/PED_2_3X_ACS_Cancer_Detection_Guideleines_36.asp. Accessed November 15, 2009.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Guidelines for detection, prevention & risk reduction. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp#detection. Accessed November 15, 2009.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/uspstf/uspsbrgen.htm. Accessed November 15, 2009.

Bonis PA, Trikalinos TA, Chung M, et al. Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer: diagnostic strategies and their implications. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 150 (prepared by Tufts-New England Medical Center Evidence-Based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0022). AHRQ Publication No. 07-E008. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2007.

Scheuner MT, Wang SJ, Raffel LJ, Larabell SK, Rotter JI . Family history: a comprehensive genetic risk assessment method for the chronic conditions of adulthood. Am J Med Genet 1997; 71: 315–324.

Hampel H, Sweet K, Westman JA, Offit K, Eng C . Referral for cancer genteics consultation: a review and compilation of risk assessment criteria. J Med Genet 2004; 41: 81–91.

Scheuner MT, Yoon PW, Khoury MJ . Contribution of Mendelian disorders to common chronic disease: opportunities for recognition, intervention and prevention. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2004; 125C: 50–65.

Wattendorf DJ, Hadley DW . Family history: the three-generation pedigree. Am Fam Physician 2005; 72: 441–448.

Ramsey SD, Yoon PW, Moonesinghe R, Khoury MJ . Population-based study of the prevalence of family history of cancer: implications for cancer screening and prevention. Genet Med 2006; 8: 571–575.

Vasen HF, Watson P, Mecklin JP, Lynch HT . New clinical criteria for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, Lynch syndrome) proposed by the International Collaborative group on HNPCC. Gastroenterology 1999; 116: 1453–1456.

Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, et al. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004; 96: 261–268.

Ponz de Leon M, Bertario L, Genuardi M, et al. Identification and classification of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome): adapting old concepts to recent advancements. Report for the Italian Association for the Study of Hereditary Colorectal Tumors Consensus Group. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50: 2126–2134.

Murff HJ, Spigel DR, Syngal S . Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA 2004; 292: 1480–1489.

Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H . Validation of family history data in cancer family registries. Am J Prev Med 2003; 24: 190–198.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2009. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/STT/STT_0.asp. Accessed November 23, 2009.

Brandt A, Bermejo JL, Sundquist J, Hemminki K . Age of onset in familial breast cancer as background data for medical surveillance. Br J Cancer 2010; 102: 42–47.

Zell JA, Honda J, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver H . Survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis is associated with colorectal cancer family history. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2008; 17: 3134–3140.

Stigliano V, Assisi D, Cosimelli M, et al. Survival of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer patients compared with sporadic colorectal cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2008; 27: 39.

Highighi MM, Vahedi M, Mohebbi SR, Pourhoseingholi MA, Fatemi SR, Zali MR . Comparison of survival between patients with hereditary non polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) and sporadic colorectal cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2009; 10: 497–500.

Soegaard M, Frederiksen K, Jensen A, et al. Risk of ovarian cancer in women with first-degree relatives with cancer. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2009; 88: 449–456.

Liu JF, Hirsch MS, Lee H, Matulonis UA . Prognosis and hormone receptor status in older and younger patients with advanced-stage papillary serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 2009; 115: 401–406.

Watson P, Bützow R, Lynch HT, et al. the International Collaborative Group on HNPCC The clinical features of ovarian cancer in hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2001; 82: 223–228.

Grindedal EM, Renkonen-Sinisalo L, Vasen H, et al. Survival in women with MMR mutations and ovarian cancer; a multicentre study in Lynch syndrome kindreds. J Med Genet 2010; 47: 99–102.

Bergmann MM, Calle EE, Mervis CA, Miracle-McMahill HL, Thun MJ, Heath CW . Validity of self-reported cancers in a prospective cohort study in comparison with data from state cancer registries. Am J Epidemiol 1998; 147: 556–562.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a contract from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scheuner, M., McNeel, T. & Freedman, A. Population prevalence of familial cancer and common hereditary cancer syndromes. The 2005 California Health Interview Survey. Genet Med 12, 726–735 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f30e9e

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181f30e9e

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Improving primary care identification of familial breast cancer risk using proactive invitation and decision support

Familial Cancer (2021)

-

At the intersection of precision medicine and population health: an implementation-effectiveness study of family health history based systematic risk assessment in primary care

BMC Health Services Research (2020)

-

Effectiveness of interventions to identify and manage patients with familial cancer risk in primary care: a systematic review

Journal of Community Genetics (2020)

-

Personalized medicine for prevention: can risk stratified screening decrease colorectal cancer mortality at an acceptable cost?

Cancer Causes & Control (2017)

-

ACG Clinical Guideline: Genetic Testing and Management of Hereditary Gastrointestinal Cancer Syndromes

American Journal of Gastroenterology (2015)