Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the repeatability of clinical decision-making by one glaucoma specialist and determine the influence of intraocular pressure (IOP) variation on those decisions.

Patients and methods

40 patients were selected in whom consultant decisions were appropriate concerning management. These notes were reviewed on three separate occasions, each 3 months apart. The final examination was changed to include clinical findings with the IOP, either the same, ±2 or ±4 mm Hg different from the recorded IOP. A forced choice clinical decision was made on each occasion: continue present treatment, change medical treatment, or recommend surgery. The clinical decisions were then compared.

Results

Our results showed that when the presented IOP was the same there was an 80% agreement in the management decision (κ0.7).

When the presented IOP was lowered by 2 or 4 mm Hg the agreement was 70 and 85%, respectively. When the presented IOP was increased by 2 or 4 mm Hg the agreement was 65 and 70%, respectively. None of these changes were significantly different. Similarly there was no evidence of a trend towards disagreement with IOP change (χ2 trend=1.3 P=0.25).

Conclusions

Algorithms for decision-making in glaucoma are complex.

Large differences between specialists are recognised. This is a first report of within specialist agreement. The impact of within measurement error differences in single IOP measurements was negligible. Review of comments suggests that the main reason for disagreement was patient preference, which was absent with note review.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There has been much concentration on the accuracy of intraocular pressure (IOP) assessment in recent literature, particularly with respect to central corneal thickness.1 It is well recognised that even the current gold standard of IOP assessment is prone to measurement error. In research situations ±2 mm Hg is the norm for assessments2 and in real life anything upto ±4 mm Hg (personal experience undertaking Bland Altman assessments with staff members joining glaucoma clinic for the first time).

In the management of glaucoma there are many options and a decision to proceed to surgery is both surgeon and patient dependent. It is generally accepted that there is a large variation between individual surgeons,3 however, no estimate of within surgeon agreement exists. A second point of interest is the degree to which accuracy in single IOP assessment influences clinical decision-making. This paper reports the reproducibility of clinical decision making in one sub-specialist and the degree to which this was affected by variations in pressure readings within the errors of current practice.

Patients and methods

The records were collected of 40 patients with primary open-angle glaucoma in whom consultant advice was given within a routine clinical setting. In 13 cases a decision had been made to proceed to surgery, 3 cases had a choice to add or change topical therapy and the remainder had a choice to continue on the same therapy. The notes including visual fields were photocopied upto the date of that decision and represented to the same clinician who had made the original management decision. The clinical findings at the time of that visit were retained, but entries in the notes with respect to any clinical management decision on that occasion were masked.

The notes were represented to the clinician on three occasions, each time separated by a period of at least 3 months to minimise any memory effect. For each presentation the IOP recorded in the notes for the final visit at which the decision was made was varied. For every patient the IOP was presented as the same on one occasion, and lower (−2 or −4 mm Hg) and higher (+2 or +4 mm Hg) on the other two occasions. Five comparison groups were created (Table 1).

The degree of variability of IOP from original measurement was randomised for each patient so the ophthalmologist making the decision had no idea of the degree of variation at the time of decision-making.

Results

The agreement for each group is shown in Table 1.

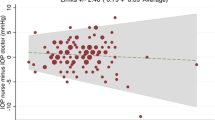

With no variation in IOP the free marginal κ was 0.70, which is generally accepted as ‘good’ agreement. Agreement in management decision ranged from 65–85% (overall χ2=3.2 P=0.5. individual χ comparing each IOP change against no change P=0.21–0.64). There was no clear trend across IOP change (χ2 trend=1.3 P=0.25).

There were three patients listed for surgery in clinic in whom none of the three second reviews agreed with that clinical decision. Review of these disagreements showed them not to be so polar opposites as they first appear, since comments in the clinic and on subsequent note review all detailed a discussion or need to discuss surgical options with the patient.

Discussion

It would be a mistake to make too much of these findings, as they only represent one ophthalmologist and the study design has limitations. A major part of clinical decision making is in discussion with patients and this is inevitably missing from the subsequent notes review. In addition, there is always a possibility of result bias due to clinician memory of cases, although the time interval between note reviews was aimed at reducing this. Nonetheless this does represent a first attempt at estimating the reproducibility of major clinical management decision-making. How good the agreement is, is a matter of debate. It could be said that an agreement on surgical intervention in only half of the cases (see ±2 mm Hg results) listed in real life is not good, or it could be said that the relative independence of exact IOP and broad agreement despite the lack of consultation with patients has quite a reassuring degree of robustness.

The cases were selected as those requiring consultant decision, hence these findings are a worst case scenario as a majority of patients in a glaucoma clinic have straightforward clinical decision-making being either stable or else very clearly out of control.

The variety of clinical opinion between clinicians has been well illustrated by Weinreb3 in his editorial on clinical decision making in cyberspace. Mantravadi et al4 demonstrate clearly the problems with surrogate decision-making for cataract surgery. This work shows a reasonable degree of consistency within one observer.

Over the last 20 years McKinley has published widely on this topic with a variety of co-workers.5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Starting from Eisenberg's advice to describe decision-making in the context of ‘sociologic influences’ he found that variability in decision-making between physicians for dyspnoea and chest pain was ‘not entirely accounted for by…Baysian inference’. He found non-medical factors significant in affecting decisions.5 Ever since that paper he has undertaken several large studies aimed at determining the various contributions of patient, physician, and health-care system influences on decision-making. The results seem to vary for different disease states. Decisions in coronary heart disease and depression were influenced by patient's age, colour, and gender, in addition to physician gender.6, 7 In another study of polymyalgia rheumatica and depression he found that patient attributes had no influence but physician's specialty, age, and colour influenced decision-making.8 Similarly, patient characteristics had no role in decision-making for breast cancer (apart from certainty of diagnosis which was higher for higher patient socioeconomic status).9 To what extent these factors account for the residual variation here is unclear. As it was the same physician doing the assessment, only patient information would be likely to have an influence and the age of the patient was the only information available on review (although clearly colour, sex, and other factors would be evident at the original consultation). Either way it seems likely that these factors would have a smaller role.

The reaction of the patient is much more likely to be a strong influence in this situation. A patient may be hesitant or very receptive and it is only correct that the doctor takes into account that patient's attitude and wishes. Some cases may indeed have two reasonable courses of action and the decision of the same doctor on two different days will differ and indeed two different doctors may have very reasonable differences of management approach.

Decision-making is a complex process of interpretation of clinical investigations (IOP, fields, discs, and others), current therapeutic issues (compliance, side-effects, and social situation), and patient preference. It is well established that interpretation of investigations is variable, a prime example in glaucoma being visual fields.10 The relative independence of decision agreement from IOP variation within normal errors of estimate for a single reading suggests a wider use of available information in the decision-making process. Compliance, side effects and social situations are not always clearly documented in notes. Finally, patient preference is recorded when strong but, certainly, generally not recorded in any systematic manner. Perhaps there is a place for reviewing our clinical documentation in these regards?

References

Chihara E . Assessment of true intraocular pressure: the gap between theory and practical data. Surv Ophthalmol 2008; 53: 203–218.

AlMubrad TM, Ogbuehi KC . The effect of repeated applanation on subsequent IOP measurements. Clin Exp Optom 2008; 91 (6): 524–529.

Weinreb RN . Clinical decision-making in cyberspace. J Glaucoma 1997; 6 (1): 1–2.

Mantravadi AV, Sheth BP, Gonnering RS, Covert DJ . Accuracy of surrogate decision making in elective surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 2007; 33: 2091–2097.

McKinlay JB, Potter DA, Feldman HA . Non-medical influences on medical decision-making. Soc Sci Med 1996; 42 (5): 769–776.

Mc Kinley J, Link C, Marceau L, O'Donnell A, Arber S, Adams A et al. How do doctors in different countries manage the same patient? Results of a factorial experiment. Health Serv Res 2006; 41 (6): 2182–2200.

Arber S, McKinley J, Adams A, Marceau L, Link C, O'Donnell A . Influence of patient characteristics on doctors' questioning and lifestyle advice for coronary heart disease: a UK/US video experiment. Br J Gen Pract 2004; 54 (506): 673–678.

McKinley JB, Lin T, Freund K, Moskowitz M . The unexpected influence of physician attributes on clinical decisions: results of an experiment. J Health Soc Behav 2002; 43 (1): 92–106.

McKinley JB, Burns RB, Feldman HA, Freund KM, Irish JT, Kasten LE et al. Physician variability and uncertainty in the management of breast cancer. Results from a factorial experiment. Med Care 1998; 36 (3): 385–396.

Chauhan BC, Garway-Health DF, Goni FJ, Rossetti L, Bengtsson B, Ciswanathan AC et al. Practical recommendations for measuring rates of visual field change in glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol 2008; 92: 569–573.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the review process. Our reviewers have contributed to the presentation of our results and discussion.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Murdoch, I., Johnston, R. Consultant clinical decision making in a glaucoma clinic. Eye 24, 1028–1030 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.255

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2009.255