Key Points

-

Provides evidence to inform workforce planning.

-

Identifies potential barriers to the future employment of dental hygienist-therapists in general dental practice.

-

Highlights a need to ensure that all members of the dental team understand the roles and responsibilities of colleagues.

Abstract

Aim To examine the attitudes of general dental practitioners in Wales with regard to the employment of dually-qualified hygienist-therapists.

Design Questionnaire.

Results Responses were received from the principals of 332 of the 550 practices surveyed, a response rate of 60.4%. Fifty-four percent of responding principals currently employed a hygienist and 9% a dually-qualified hygienist-therapist; 43% considered that they were likely to employ hygienist-therapists in the future. Lack of surgery space to accommodate a hygienist-therapist was a problem facing many principals. Disappointingly, respondents demonstrated a clear lack of knowledge in relation to the cost effectiveness of hygienist-therapists, with 39% of principals admitting that this individual would be expected to spend more than half their working time on hygiene treatment. Sixty percent of principals placed an associate among their first three preferences to fill spare capacity, while only 28% selected a hygienist-therapist.

Conclusion This study has provided local evidence to inform workforce planning and identified a need to ensure that all members of the dental team understand the roles and responsibilities of colleagues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With both need and demand for dental care far exceeding the capacity of the profession to provide full and responsive services, attention is currently turning to dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists as being of increasing importance in the delivery of care.1 In Wales, there is at present little accurate information as to how many hygienist-therapists are employed in general practice; similarly, there has long been a dearth of relevant information to support workforce planning. Indeed, Hay and Batchelor,2 in a paper published in 1993, were the last authors to include Wales in any examination of their future role. The present study, therefore, aimed to examine the attitudes of general dental practice principals in Wales with regard to the employment of this category of dental care professional. It was carried out between July and September 2005.

Materials and Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was developed following a review of the relevant literature and discussion with dental practitioners, hygienists, therapists and colleagues in dental public health. The instrument consisted of 12 open and closed questions. A pilot study involving ten dentists working at Cardiff University School of Dentistry was undertaken, resulting in the addition of a free-text comment section.

General dental practices (NHS and private) in Wales were identified from the database held by the Department of Dental Postgraduate Education. The principal of each practice was sent a copy of the questionnaire, accompanied by a covering letter and a postage-paid envelope for its return. In order to allow the identification of non-respondents, each questionnaire was coded, a code-break being kept by a third party not directly involved in the study. In an attempt to improve the response rate, non-respondents were followed up by telephone and offered the option of completing the questionnaire in this way (administered unchanged and without prompt by the investigator (RD)). In the event that the principal was unable to spare the time to complete the questionnaire at this time, every attempt was made to arrange a mutually convenient time at which this could be achieved. Those principals who stated that they had not received a postal questionnaire in the first mailing and who expressed a preference for completing the study in this way were included in a second mailing, with the option of receiving and returning the questionnaire by fax.

Data entry and analysis was accomplished using Microsoft Excel software, standard qualitative methods of data analysis being used in relation to the 'open' questions.

Results

Five hundred and fifty general dental practices were identified. Following the first mailing, 244 questionnaires were returned, an initial response rate of 44.4%. Subsequent to follow-up telephone calls and the second mailing, a further 88 complete questionnaires were collected, resulting in a final response rate of 332 (60.4%). Of these additional 88, 36 were postal responses, 29 were telephone responses and 23 were faxed responses. Table 1 illustrates the response rate for each of seven regions in Wales, together with the contribution of each to the overall response rate.

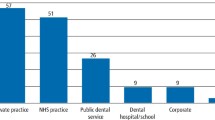

One hundred and eighty principals (54.2% of all respondents) stated that they had a hygienist and 30 (9.0% of all respondents) a hygienist-therapist as part of their team. Of the 302 principals who did not already employ a hygienist-therapist, 301 indicated their likely future intention with regard to doing so.

The majority (132; 82.5%) of the 160 principals who already employed a hygienist-therapist or would consider doing so indicated that they would require a hygienist-therapist to undertake both hygiene and therapy treatment. There was, however, a lack of consensus as to the nature of the contract of employment which would be offered to the individual. Seventy-three principals (22.0%) indicated that the hygienist-therapist should be employed, while 95 (28.6%) thought that he/she should be self-employed. One hundred and ten principals (33.1%) stated no preference with regard to the nature of the contract of employment, while 54 (16.3%) did not answer this question.

Thirteen respondents (3.9%) stated that they would never provide a dental nurse to assist a hygienist-therapist. Two hundred and fourteen (64.5%) stated that they would always provide this support, while 64 (19.3%) indicated that they would occasionally do so. Forty-one principals (12.3%) did not respond to this question.

Interestingly, when this question was asked in relation to the support of a hygienist, 39 principals (11.7%) stated that they would never provide a dental nurse. One hundred and twenty-five (37.7%) stated that they would always provide this support, while 140 (42.2%) indicated that they would occasionally do so. Twenty-eight principals (8.4%) did not respond to this question.

As surgery availability is a potential obstacle to the employment of hygienist-therapists, principals were asked whether they could offer any spare capacity during the course of the week. One hundred and forty-seven principals (44.3%) stated that their practices had no spare capacity. One hundred and fourteen responding principals (34.3%) stated that they could offer spare capacity on between one and four sessions per week, with fewer (27 (8.1%) and 37 (11.2%) respectively) being able to offer five to eight or nine or more sessions per week.

When asked to consider how any spare capacity might best be filled, 142 responding practices mentioned a hygienist among their top three preferences, while 115 mentioned a therapist. To put these responses in context, 194 practices placed an associate among their first three preferences.

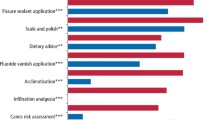

In the questionnaire's penultimate section, practitioners were asked to indicate their level of agreement with seven specific statements relating to the employment of therapists as part of the dental team. Their responses are summarised in Table 2.

Finally, principals were given the opportunity to add free-text comment. Only 48 respondents availed themselves of this opportunity. Qualitative analysis of these comments identified five recurring themes: cost-effectiveness, knowledge of the role of a hygienist-therapist, accommodation, and patient and practitioner acceptance. In the following paragraphs, typical comments are quoted verbatim by way of illustration.

Cost-effectiveness

A number of negative comments were received in relation to the cost-effectiveness of employing therapists. One dentist wrote: 'Therapists' and hygienists' expected salaries are disproportional of their earning and productivity capacity.'

Another commented: 'We have heard that therapists are asking for £30 per hour. They would not be cost-effective on this rate. If you add on the nurses cost and materials per hour, therapists would have to gross £50-60 per hour in order to lower cost.' Other dentists stated that they believed that therapists would not be cost-effective until they were allowed to carry out a basic examination and formulate a treatment plan, relieving the dentist of having to personally see and assess every patient.

Respondents were uncertain as to how the new contract (implemented on 1 April 2006) would affect hygienist-therapists. The following comments are representative of the opposing views propounded:

'With the new contract it will be cost-effective to have therapists.'

'The terms of the upcoming new contract make employment of therapists and hygienists financially non viable.'

Knowledge

There was a clear lack of knowledge and understanding in relation to how a therapist may be utilised within a dental team and at the same time be cost-effective. Indeed, one dentist remarked: 'We just don't know enough to answer our own or your questions... more information would be helpful to all.' Another commented: 'I do not know enough about the role of therapists to comment.'

Accommodation

The results presented above indicated that surgery space was a problem in many practices and this was reflected in the free-text comments. One stated: 'Therapists and hygienists are non-affordable in small practices since they command high hourly rates... But I believe they would be very valuable in larger practices.' Others commented that, due to the large workload, spare capacity would be more suited to employing another dentist rather than a hygienist-therapist.

Patient acceptance

Table 2 shows that just over 45% of respondents did not know whether their patients would be happy to be referred to a hygienist-therapist. The free-text comment was more illuminating, one practitioner commenting: 'Due to lack of info, therapists are not as widespread as they should be therefore patients are reluctant to see them.' Two dentists provided an interesting perspective on the potential employment prospects for hygienist-therapists in private practice, feeling that patients who were paying for treatment in this way would prefer to be seen by the dentist.

Practitioner acceptance

The results indicated that dentists were willing to accept hygienist-therapists but there was clearly a lack of knowledge in terms of the role they can play within the team. One dentist remarked: 'Therapists are great – gives the dentist the opportunity to do more complex treatment rather than less skilled work which is more time consuming.' Other comments included: 'Hygienists are essential to practice. Some patients don't go to DCPs. People are poorly educated on what DCPs can do', and 'tremendous shortage, therefore need more therapists. I believe the future are therapists being part of the dental team.'

While some practitioners had a negative outlook towards hygienist-therapists, suggesting that they lacked the confidence and ability to take charge and work as part of a team, there was a general recognition that dental care would be best delivered by a team in which there was an appropriate skill mix.

Discussion

The results presented above are essential for forward planning in relation to hygienist-therapist training, since they give a picture of the kind of skill mix which dentists in Wales are likely to wish to achieve in their practices. In addition, since the demographic characteristics of the sample (in respect of type and location of practices) were similar to those of the UK as a whole, the findings may be generalisable.

Responding principals were generally favourably disposed towards hygienist-therapists, with 43% being prepared to consider employing one. This is a similar figure to that reported by Hay and Batchelor.2

In this study, general dental practitioners demonstrated a clear lack of knowledge in relation to the cost effectiveness of adopting hygienist-therapists in general practice. This should not be surprising, since both Gallagher and Wright3 and Ross and co-workers4 have previously contended that, in general, dentists have little knowledge of the training and work practices of dental therapists. This is a governance issue which the GDC could address by providing all registrants with details of the procedures which each category of dental care professional (DCP) can/cannot undertake and the level of supervision required.5

Harris and Burnside6 suggested that therapists are not cost-effective. However, this conclusion was reached on a quantitative, item for service basis only. To understand the full cost-effectiveness of hygienist-therapists and other DCPs, one must understand the use of these colleagues to meet service demands that cannot be met by the dentists currently working in practice.5 If a varied skill-mix dental environment (as exemplified by Ward1) is adopted, tasks can be appropriately delegated; this has the benefit of encouraging health promotion and improving quality of care as well as the working lives of the members of the dental team.

Sprod and Boyles7 have suggested that larger practices and the use of DCPs offer advantages of both productivity and efficiency. However, they have emphasised that the decision to expand or employ hygienist-therapists relies on the subjective assessment of service demands by the individual general dental practitioner who will also bear the responsibility and risk of making such decisions. It is clear, therefore, that it is essential that practices require support not only in respect of finance but through improved needs assessment.

With the recent changes to the dental contract and the introduction of units of dental activity, general dental practitioners will need to plan payment for dental therapists carefully: practice profitability under the new system of remuneration could be improved by employing hygienist-therapists on an hourly rate.

Capacity to accommodate a hygienist-therapist was a problem faced in many practices. This is not a problem which is unique either to Wales or to this category of DCP: Sprod and Boyles7 found a similar situation in the South West of England, where over 60% of respondents stated that they did not employ a hygienist due to lack of space to accommodate them. An infrastructure where the majority of practices have no more than two surgeries provides a major obstacle if it is envisaged that considerable numbers of therapists will, in the future, be providing care. The main issue here is finance: unlike general medical practice, there has, until recently, been no support for capital development of dental practice. In 2001, the Government provided £35 million for the modernisation of NHS dental practices. Gallagher and Wright,3 writing in the same year, expressed the hope that the introduction of public private partnership through NHS LIFT would provide opportunities for the capital development of dental practices.

In our study, the majority of responding principals employed a hygienist as part of their team. Interestingly, despite this, the majority did not know whether their adult patients would be happy to be referred to a hygienist-therapist for part of their treatment. In addition, respondents' views as to whether hygienist-therapists would spend more than half their time on hygiene work show a clear lack of understanding of the role of these individuals in the dental team.

For effective planning of hygienist-therapists' training in Wales, future workforce requirements need to be reviewed constantly. This study, as well as others conducted over the last two decades,1,2,3,4 has identified barriers to the employment of hygienist-therapists in general practice. Lack of knowledge regarding these DCPs has profound affects on their acceptance by both the dental profession and the public. The authors advocate that the training of hygienist-therapists should be integrated with that of dental undergraduates in order that their true value is understood from an early stage.

References

Ward P . The changing skill mix – experiences on the introduction of the dental therapist into general dental practice. Br Dent J 2006; 200: 193–197.

Hay I S, Batchelor P A . The future role of dental therapists in the UK: a survey of district dental officers and general dental practitioners in England and Wales. Br Dent J 1993; 175: 61–65.

Gallagher J L, Wright D A . General dental practitioners' knowledge of and attitudes towards the employment of dental therapists in general practice. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 37–41.

Ross M K, Ibbetson R J, Turner S . The acceptability of dually-qualified dental hygienist-therapists to general dental practitioners in South-East Scotland. Br Dent J 2007; 202: E8. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.45

Harris R V, Haycox A . The role of team dentistry in improving access to dental care in the UK. Br Dent J 2001; 190: 353–356.

Harris R, Burnside G . The role of dental therapists working in four personal dental service pilots: type of patients seen, work undertaken and cost effectiveness within the context of the dental practice. Br Dent J 2004; 197: 491–496.

Sprod A, Boyles J . The workforce of professionals complementary to dentistry in the general dental practices in the South West. Br Dent J 2003; 194: 389–397.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Refereed Paper

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, G., Devalia, R. & Hunter, L. Attitudes of general dental practitioners in Wales towards employing dental hygienist-therapists. Br Dent J 203, E19 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.890

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2007.890

This article is cited by

-

Assessing the efficacy and social acceptability of using hygienist-therapists as front-line clinicians

BDJ Team (2017)

-

Feasibility study: assessing the efficacy and social acceptability of using dental hygienist-therapists as front-line clinicians

British Dental Journal (2016)

-

Dental skill mix: a cross-sectional analysis of delegation practices between dental and dental hygiene-therapy students involved in team training in the South of England

Human Resources for Health (2014)

-

Supporting newly qualified dental therapists into practice: a longitudinal evaluation of a foundation training scheme for dental therapists (TFT)

British Dental Journal (2013)

-

Skill-mix in dental teams in Wales

Vital (2013)