Abstract

Treatment-related acute myeloid leukaemia (t-AML) is a serious complication of topoisomerase 2 inhibitor therapy and is characterised by the presence of mixed lineage leukaemia (MLL) rearrangement. By molecular tracking, we were able to show that MLL cleavage preceded gene rearrangement by 3 months and before the clinical diagnosis of t-AML in a patient with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. This is the first report on the sequential detection of the two biomarkers in treatment-related leukaemogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The relationship between topoisomerase 2 (topo 2) inhibitor therapy and the pathogenesis of treatment-related acute myeloid leukaemia (t-AML) with rearrangements of the mixed lineage leukaemia (MLL) gene is now well documented (Felix, 1998; Pui and Relling, 2002). This type of t-AML tends to have a myelomonocytic/monoblastic phenotype and rearrangements of the MLL gene with multiple partners. Cytogenetic analysis has revealed a median latency from primary disease to t-AML of 24 months (range 10–100 months). In addition to its clinical importance as an adverse outcome of chemotherapy, t-AML provides an opportunity to investigate the timing of the molecular events involved in the pathogenesis of this condition in relation to the administration of topo 2 inhibitor therapy. We have backtracked the molecular events from a t-AML in a child with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-related haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).

Patient and method

The patient was an 18-month-old boy, diagnosed with EBV-related HLH, and treated according to the HLH-94 protocol (Henter et al, 1997) with dexamethasone, intrathecal methotrexate and intravenous etoposide (150 mg m−2) given twice weekly in the first 2 weeks and then weekly for 5 weeks (cumulative etoposide dose: 1.35 g m−2). At 2 months after the start of treatment, the patient was in complete remission, but by the 6th month after HLH diagnosis (4 months after treatment ceased), he presented with jaw swelling and cervical lymphadenopathy. Bone marrow examination revealed 70% infiltration with myeloid blasts, confirmed by cytochemistry and immunophenotyping as monoblastic AML. There was no CNS involvement by leukaemia. Interphase cytogenetics of the bone marrow showed a chromosome 9;11 translocation (47, XY, +8, t(9;11)(p22;q23)). The patient received induction chemotherapy (daunorubicin, cytarabine and thioguanine) for his AML according to the MRC 10th AML trial (Stevens et al, 1998) and achieved remission. At 5 months after the diagnosis of t-AML, he was successfully transplanted with non-T-cell-depleted bone marrow from an HLA-matched unrelated donor, following conditioning with cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation. He remains in complete remission 28 months post-transplantation.

We collected serial blood and bone marrow samples at the time of the patient's HLH diagnosis, and thereafter at weekly intervals for 6 weeks, and then again at 3 and 6 months. Prior approval for the study was obtained from the local research ethics committee. Genomic DNA extracted from immediately frozen samples was digested with BamH1 and analysed for etoposide-induced MLL cleavage (Aplan et al, 1996) and rearrangement, using a 0.74 kb cDNA probe spanning the MLL breakpoint cluster region (BCR). The DNA was size fractionated by 0.7% agarose gel electrophoresis, and blotted onto nylon membranes. MLL cleavage was detected, after hybridisation overnight at 60°C with the 32P-labelled MLL probe, using real-time autoradiography. Panhandle PCR method (Felix and Jones, 1998) was also used to analyse the same serial blood and bone marrow samples for MLL rearrangement.

Results

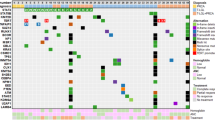

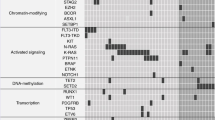

We detected no MLL cleavage in any of the peripheral blood samples obtained up to the appearance of overt t-AML, 6 months after the diagnosis of HLH. However, a 6.7 kb MLL cleavage fragment, identical to that detected when we incubated the haemopoietic cell line BV173 in vitro with 10 μ M etoposide for 6 h, was detected in the bone marrow (morphologically <5% blasts and no circulating blast seen) obtained 3 months after HLH diagnosis, 1 month after the last dose of etoposide (cumulative dose: 1.35 g m−2) and 3 months prior to the diagnosis of overt t-AML. Analysis of Southern blots of the same BamH1-digested DNA samples revealed two rearranged MLL fragments (5.6, 18 kb), in addition to the 8.3 kb germline MLL fragment, only in the bone marrow obtained at the time of t-AML diagnosis (Figures 1 and 2). Panhandle PCR confirmed the presence of MLL rearrangement and the 5.6 kb der (11) MLL PCR product was only detected in the same bone marrow sample (Figure 3). This was 4 months after HLH therapy was stopped, and 3 months after the detection of MLL cleavage in the bone marrow.

Southern blot analysis of serial samples for MLL cleavage and rearrangement. InstantImager bitmap showing the detection of 32P-labelled MLL probe hybridisation. MLL cleavage fragment (6.7 kb) was identified in the bone marrow 3 months after the start of etoposide therapy. MLL rearranged fragments (5.6, 18 kb) and germline BCR fragment (8.3 kb) were only detected at the clinical presentation of t-AML. MLL rearrangement resolved with further chemotherapy prior to the bone marrow transplant. D – day; W – week; M – month, from the diagnosis of HLH; ↓ – clinical presentation of t-AML; BM – bone marrow; MUD – matched, unrelated donor transplant.

Panhandle PCR on the same samples for the detection of MLL rearrangement. Gel doc image showing the panhandle PCR product (5.6 kb) after agarose gel electrophoresis. It was only detected in the patient's bone marrow 6 months after the start of etoposide therapy. Negative controls: UL – unligated, H2O – water; BM – bone marrow; D – day; W – week; M – month, from the diagnosis of HLH.

Discussion

The occurrence of t-AML involving MLL rearrangements with a latent period of 24–36 months has previously been reported in HLH (Takahashi et al, 1998; Kitazawa et al, 2001). Based on the clinical evidence alone, the latent period from the start of therapy until the diagnosis of overt t-AML in our patient was only 6 months. However, using molecular tracking, we have shown prospectively that etoposide-induced MLL cleavage preceded MLL rearrangement by 3 months, and furthermore, using the panhandle PCR method, that MLL rearrangement could only be detected at the diagnosis of t-AML. As no DNA samples were available to us in the time period between 3 and 6 months after HLH diagnosis, our conservative estimate is that the t-AML clone emerged during a period ⩽3 months. Cytogenetic and provisional sequencing data conclude that the rearrangement involved AF9 as the partner gene, with nucleotides insertion within the breakpoint junction (intron 6 of MLL, intron 4 of AF9) of the fusion gene.

Our results differ from those reported by Megonigal et al (2000), who detected a leukaemic clone with MLL-GAS7 within 6 weeks of the start of neuroblastoma therapy including doxorubicin. This was some 15.5 months before the appearance of clinically overt t-AML. The result that we obtained suggests that once established, the putative MLL-AF9 leukaemic clone developed much more rapidly into overt AML as compared to the MLL-GAS7 clone. It also suggests that partner sequences in MLL fusion genes could modify the leukaemogenic process.

As far as we are aware, this is the first case of t-AML in which MLL cleavage and rearrangement have been detected consecutively in a patient developing t-AML. Our finding thus suggests that the two are temporally related, with gene cleavage and DNA processing prior to translocation, as proposed in the work by Lovett et al (2001).

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Aplan PD, Chervinsky DS, Stanulla M, Burhans WC (1996) Site-specific DNA cleavage within the MLL breakpoint cluster region induced by topoisomerase 2 inhibitors. Blood 87: 2649–2658

Felix CA (1998) Secondary leukaemias induced by topoisomerase-targeted drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1400: 233–255

Felix CA, Jones DH (1998) Panhandle PCR: a technical advance to amplify MLL genomic translocation breakpoints. Leukemia 12: 976–981

Henter JI, Arico M, Egeler RM, Elinder G, Favera BE, Filipovich AH, Gadner H, Imashuku S, Janka-Schaub G, Komp D, Ladisch S, Web D (1997) HLH-94: a treatment protocol for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Med Pediatr Oncol 28: 342–347

Kitazawa J, Ito E, Arai K, Yokoyama M, Fukayama M, Imashuku S (2001) Secondary acute myelocytic leukemia after successful chemotherapy with etoposide for Epstein–Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Med Pediatr Oncol 37: 153–154

Lovett BD, Nigro LL, Rappaport EF, Blair IA, Osheroff N, Zheng N, Megonigal MD, Williams WR, Nowell PC, Felix CA (2001) Near-precise interchromosomal recombination and functional DNA topoisomerase 2 cleavage sites at MLL and AF-4 genomic breakpoints in treatment-related acute lymphoblastic leukemia with t(4;11) translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 9802–9807

Megonigal MD, Cheung N-KV, Rappaport EF, Nowell PC, Wilson RB, Jones DH, Addya K, Leonard DGB, Kushner BH, Williams TM, Lange BJ, Felix CA (2000) Detection of leukaemia-associated MLL-GAS7 translocation early during chemotherapy with DNA topoisomerase 2 inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 2814–2819

Pui CH, Relling MV (2002) Topoisomerase 2 inhibitor-related acute myeloid leukaemia. Br J Haematol 109: 13–23

Stevens RF, Hann IM, Wheatley K, Gray RG (1998) Marked improvements in outcome with chemotherapy alone in paediatric acute myeloid leukaemia: results of the United Kingdom Medical Research Council's 10th AML trial. MRC Childhood Leukaemia Working Party. Br J Haematol 101: 130–140

Takahashi T, Yagasaki F, Endo K, Takahashi M, Itoh Y, Kawai N, Kusumoto S, Murohashi I, Bessho M, Hirashima K (1998) Therapy-related AML after successful chemotherapy with low dose etoposide for virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. Int J Hematol 68: 333–336

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Michael J Thirman, University of Chicago, for the MLL probe.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Ng, A., Ravetto, P., Taylor, G. et al. Coexistence of treatment-related MLL cleavage and rearrangement in a child with haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Cancer 91, 1990–1992 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602269

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602269