Abstract

Since the human-assisted movement of the Cape honeybee Apis mellifera capensis out of its native territory, its workers have invaded colonies of the African honeybee A. m. scutellata. When this happens, their ovaries develop and they begin to reproduce1, which results in the death of the scutellata queen, and eventually in either the death of the colony or the production of a capensis (worker-produced) queen1. We have found that capensis larvae alter the behaviour of non-capensis workers and receive royal treatment, resulting in adult females with queenlike characteristics (pseudoqueens2,3,4).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Only twenty years ago, it was feared that A. m. scutellata would out-compete A. m. capensis2, but instead capensis workers have invaded scutellata colonies5. This causes ‘dwindling colony’ syndrome1, in which the scutellata queen is rejected and capensis workers start laying eggs. Unlike the workers of other Apis races, which lay haploid eggs, workers of capensis produce diploid eggs by thelytoky, which develop into either workers or queens2.

The presence of laying capensis workers prevents the rearing of an emergency queen6. Ultimately, the colony dies, owing to the increase of laying capensis workers and a decrease in foraging and brood care; or the laying workers are superseded by a capensis queen1.

Caste in honeybees is normally determined by the selective feeding of female larvae: those destined to be queens are fed royal jelly and receive more food than those destined to be workers, leading to a morphologically distinct queen caste. It is generally assumed that brood in social Hymenoptera possess no power over caste determination, except in social parasites7. We found, however, that capensis brood can control caste fate, which may be important in usurping non-capensis colonies.

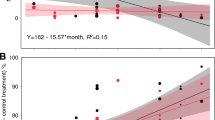

A. m. capensis brood nursed by European workers are given more food than European larvae (Table 1) — indeed, they receive more food than when they are nursed by capensis workers. In addition, the food composition was slightly more similar to royal jelly8. This resulted in the production of queen-like capensis workers (Fig. 1). The functional worker characteristics (pollen combs and pollen baskets on the hind legs) of capensis workers raised in European colonies decreased9, whereas their queen characteristics9 (short developmental time, weight, a large spermatheca and a large number of ovarioles) increased.

A. m. capensis larvae show an increase in the number of hairs between the two lowest pollen combs on the basitarsus (a), fresh weight at emergence (b), size of the spermatheca (c), and total number of ovarioles (d). The duration of the capped period decreased (e). All measured characteristics were significantly different between the two groups (one-way multiple analysis of variance, P≪0.001 when the whole data set was compared. Characteristics were then tested separately using a post-hoc least-significant difference comparison: *P<0.01, ***P≪0.001). A frame with A. m. capensis eggs (0–24 hours old) was transferred into a European honeybee colony (hybrids of A. m. carnica and A. m. mellifera). At the same time, a frame of capensis eggs laid within the same interval remained in the capensis colony. Colonies were of similar size and kept at the same apiary in Wageningen, the Netherlands. Capping of brood cells was registered every three hours. Nine days after capping, combs were placed in an incubator (34.5 °C) and emergence of each specific cell was recorded every 15 min. Fresh weight of bees was measured upon emergence, after which the bees were stored individually in 70% ethanol until further measurements were made. Oval data points are outliers.

Royal treatment of capensis brood by European workers has the same effect as juvenile hormone9. Both affect the complete set of caste characteristics, not just isolated morphological features. Our results show that brood in social Hymenoptera are not necessarily passive: capensis brood can manipulate their host so that the resulting workers are more queenlike and are probably better reproducers than normal capensis workers. Thus capensis is a well adapted social parasite of other bee races.

References

Hepburn, H. R. & Allsopp, M. H. S.-Afr. Tydsk. Wetenskap 90, 247–249 (1994).

Ruttner, F. Apidologie 8, 281–294 (1977).

Crewe, R. M. & Velthuis, H. H. W. Naturwissenschaften 67, 467–469 (1980).

Moritz, R. F. A., Kryger, P. & Allsopp, M. H. Nature 384, 31 (1996).

Greeff, J. M. S. Afr. J. Sci. 93, 306–308 (1997).

Allsopp, M. S. Afr. Bee J. 64, 52–57 (1992).

Nonacs, P. & Tobin, J. E. Evolution 46, 1605–1620 (1992).

Brouwers, E. V. M. J. Apic. Res. 23, 94–101 (1984).

Wirtz, P. & Beetsma, J. Ent. Exp. Appl. 15, 517–520 (1972).

Van Handel, E. Anal. Biochem. 19, 193–194 (1967).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beekman, M., Calis, J. & Boot, W. Parasitic honeybees get royal treatment. Nature 404, 723 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35008148

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/35008148

This article is cited by

-

Functional response of the hypopharyngeal glands to a social parasitism challenge in Southern African honey bee subspecies

Parasitology Research (2022)

-

The transcriptomic changes associated with the development of social parasitism in the honeybee Apis mellifera capensis

The Science of Nature (2018)

-

Honeybee worker larvae perceive queen pheromones in their food

Apidologie (2017)

-

When does cheating pay? Worker reproductive parasitism in honeybees

Insectes Sociaux (2017)

-

Context dependent bias in honeybee queen selection: swarm versus emergency queens

Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology (2016)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.