Abstract

Study design: Case report describing spontaneous Corynebacterium diptheria discitis in a patient with chronic renal failure.

Objectives: To describe this very rare form of discitis and the results of surgical and antibiotic therapy.

Setting: University Department of Neurosurgery, Turkey.

Case report: A 55-year-old man with chronic renal failure presented with acute low-back pain. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suggested discitis and osteomyelitis at the L5–S1 level. The L5–S1 disc was operated upon and the discectomy material was sent for pathological and microbiological analysis.

Results: Pathological examination revealed infection and bacterial culture grew C. diptheria. The patient was prescribed combination antibiotic therapy with vancomycin, a third-generation cephalosporin, and rifampicin. Clinical status improved after 8 weeks of therapy. Lumbar MRI revealed remission of the discitis and osteomyelitis after 10 months of follow-up.

Conclusion: Chronic renal failure patients with low-back pain should be investigated for spinal infection. These individuals are prone to low-grade infection in the form of discitis or osteomyelitis. Corynebacterium subspecies rarely cause spontaneous discitis. This case is interesting because of the unusual causal organism and the occurrence of discitis in the setting of chronic renal failure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infection and fever are very common in patients with chronic renal failure. Renal transplant recipients and patients on hemodialysis are usually immunocompromised, which renders them susceptible to multiple infectious conditions. Infection of the intervertebral disc can occur spontaneously or after surgical intervention. Corynebacterium subspecies (diptheria) very rarely cause these infections, and our review of the literature revealed only two similar cases previously reported.1,2

Case report

A 55-year-old man with chronic renal failure presented with acute low-back pain. He had been on hemodialysis for 7 months, and had no fever or any signs of infection prior to admission.

Clinical examination and laboratory findings

Neurological examination revealed weakness of the anterior tibialis and extensor hallucis longus muscles, and hypoesthesia in the L4–5 dermatomes. Lasègue's sign was positive when the hip was flexed at 45°. Laboratory investigation revealed a serum C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 73 mg/l, white blood cell count 5500/mm3, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) 70 mm/h. Apart from elevated blood urea nitrogen and creatinine related to chronic renal failure, all other laboratory parameters were normal. Blood cultures were also negative. Lumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed edema and contrast enhancement of the L5 and S1 vertebral bodies, enhancement of the L5–S1 intervertebral disc, enhancement of the paravertebral, and epidural soft tissues that caused indentation of the left S1 nerve root (Figure 1).

Imaging results at admission: (a) A postcontrast sagittal T1-weighted image with fat saturation and (b) a postcontrast axial T1-weighted image demonstrate contrast enhancement of the entire L5 vertebral body and the superior portion of the S1 vertebral body (large arrows). Also note the contrast-enhancing paravertebral and epidural soft-tissue lesions indenting the left S1 nerve root (arrow heads), and enhancement of posterior aspect of the L5–S1 intervertebral disc (small arrow)

Surgical findings

We preferred to operate instead of needle biopsy because of the increased weakness on dorsiflexion of the foot. The nerve root was found to be compromised by protruded disc in surgery. L5–S1 discectomy was performed and the nerve root was decompressed by foraminatomy. The disc material was yellow-gray in color and softer in consistency that was different from a degenerated disc. The material was sent for pathological and microbiological analyses.

Pathological and microbiological findings

Pathological examination revealed degenerating cartilage with granulation tissue formation, hemorrhage, and infiltration with lymphocytes, plasmacytes, and neutrophils. No specific cause of infection was identified. Gram staining of the disc tissue showed no bacteria, but bacterial culture revealed Corynebacterium diptheria.

Antibiotic treatment and follow-up

Testing showed that the organisms were susceptible to vancomycin, rifampicin, and cephalosporin. Initially, combination antibiotic therapy with vancomycin and a third-generation cephalosporin (ceftriaxone) was prescribed. After 4 weeks, the patient was still complaining of low-back pain and had walking difficulty. There was no fever and all neurological examination findings were normal. Laboratory testing showed that the ESR was still elevated (64 mm/h), but CRP had decreased to 14.8 mg/l. The two-drug treatment was continued for another 4 weeks.

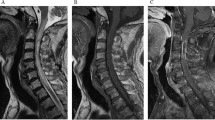

Follow-up lumbar MRI at 2 months after initial imaging showed aggravation of the epidural soft-tissue lesion. At this stage, rifampicin was added to the antibiotic regimen. After 8 weeks of triple-antibiotic therapy, testing showed that the ESR had decreased to 50 mm/h and the CRP level had dropped to 4.7 mg/l. Repeat lumbar MRI at 10 months after initial imaging revealed minimal contrast enhancement involving the entire L5–S1 intervertebral disc, and there was no significant enhancement of L5 and S1 vertebral bodies. Epidural soft-tissue enhancement was also decreased (Figure 2). Postoperative X-ray after 10 months revealed marked sclerosis of vertebral bodies secondary to long-standing inflammatory process (Figure 3).

At 10 months follow-up MRI: (a) sagittal and (b) axial postcontrast T1-weighted image with fat saturation show minimal enhancement of L5–S1 intervertebral disc (small arrow) and minimal enhancement of epidural soft tissue (large arrow). Contrary to the first MRI examination there is no significant enhancement of L5 and S1 vertebral bodies

Discussion

Spontaneous spondylodiscitis is uncommon. In such cases, diagnosis is challenging, cause is usually difficult to identify, and complications are frequent. The incidence of spontaneous discitis has risen over the past several years due to an increase in the overall frequency of pyogenic infections.2,3

The principle pathogenic mechanism in spontaneous discitis is hematogenous spread. In most cases, the person has health issues that make him or her susceptible to this type of infection. These predisposing factors include prolonged neutropenia, hematologic malignancy, chronic renal failure, chemotherapy, history of prior spinal trauma or surgery, solid-organ transplantation, and conditions that require long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.4,5,6,7

Discitis and spinal osteomyelitis have been recognized for centuries. In the past, granulomatous infection was the most common etiology in these cases; however, the rate of pyogenic infection has risen in parallel with increased numbers of immunocompromised patients.2 The causal bacteria are rarely demonstrated by direct culture or biopsy, and only 30–50% of these cases show culture growth during the clinical course.8 In one series of 1168 patients with spondylodiscitis, the most frequently isolated bacterium was Staphylococcus aureus, followed by S. albus and S. epidermidis.9 S. aureus is also the most frequent cause of spondylodiscitis in patients with chronic renal failure.3,6,7 Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Brucella spp, Escherichia coli, Proteus spp Candida albicans, Kingella kingae, and Aspergillus spp are the other rare causes of spondylodiscitis.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17

The case described in this report is particularly interesting because of the causal organism and the setting of chronic renal failure. Spontaneous spondylodiscitis due to C. diptheria is extremely rare, and only two cases have been reported to date.1,2 In humans, C. diptheria comprise part of the normal flora of the skin and nasopharyngeal region.18 We were unable to identify the focus of infection in our case; however, it is mostly likely that the organism spread to the disc space from the skin. Pruritus is a common complaint in patients with chronic renal failure, and severe itching can cause breaks in the skin. This could potentially introduce the organism to the bloodstream and lead to discitis. In addition, long-standing catheterization, frequent hemodialysis, and procedures such as arteriovenous fistulization are other potential initiators of bacteremia in patients with chronic renal disease.19

Conclusion

Low-back pain is a frequent problem in the setting of chronic renal disease. These immunocompromised patients are very susceptible to infection and bacteremia. Any individual with chronic renal disease who complains of chronic or acute low-back pain should be investigated for possible discitis.

References

Schofferman L, Schofferman J, Zucherman J, Gunthorpe H, Hsu K, Picetti G, et al. Occult infections causing persistent low back pain. Spine 1989; 14: 417–419.

Jimenez-Mejias ME Colmenero JD, Sanchez-Lora FJ, Palomino-Nicas J, Reguera JM, Garcia de la Heras J, et al. Postoperative spondylodiscitis: etiology, clinical findings, prognosis and comparison with nonoperative pyogenic spondylodiscitis. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 29: 339–345.

Tanaka N, Kasahar H, Yoshie T, Hora K, Kiyosawa K, et al. Back pain out of the blue in a haemodialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 1792–1794.

Taveras JM . Spine and spinal canal. In: Taveras JM (edn). Neuroradiology, 3rd ed. Williams and Wilkins: Baltimore 1996, pp 783–908.

Friedman JA, Maher CO, Quast LM, McClelland RL, Ebersold MJ, et al. Spontaneous disc space infections in adults. Surg Neurol 2002; 57: 81–86.

Korzets A, Weinstein T, Ori Y, Goren M, Chagnac A, Hermann M, Zevin D, et al. Back pain and Staphylococcal bacteraemia in haemodialysed patients – beware! Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 483–486.

Amir-Ansari B, Negus S, Cairns H, Walters H . Beware backache in chronic dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2000; 15: 729–730.

Stambough JL, Saenger EL . Discitis. In: Rothman RH, Simeone FA (eds). Spine, Vol. 1, 3rd edn. W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia 1992, pp 365–371.

Weber M, Gubler J, Fahrer H, Crippa M, Kissling R, Boos N, et al. Spondylodiscitis caused by Viridans streptococci: three cases and a review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 1999; 18: 417–421.

Berker M, Atalay B, Söylemezoglu F, Ariogul S, Palaoglu S, et al. Cervical tuberculous spondylitis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Spinal Cord 2001; 39: 549–553.

Martinez M, Lee AS, Hellinger WC, Kaplan J . Vertebral Aspergillus osteomyelitis and acute diskitis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Mayo Clin Proc 1999; 74: 579–583.

Morgenlander JC, Rossitch Jr E, Rawlings III CE . Aspergillus disc space infection: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery 1989; 25: 126–129.

Hennequin C, Bouree P, Hoesse C, Dupont B, Charpentier B . Spondylodiscitis due to Candida albicans: report of two patients who were successfully treated with fluconazole and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 23: 176–178.

Assaad W, Nuchikat PS, Cohen L, Esgueraa JV, Whittier FC, et al. Aspergillus discitis with acute disc abscess. Spine 1994; 19: 2226–2229.

Meis JF, Sauerwein RW, Gyssens IC, Horrevorts AM, van Kampen A, et al. Kingella kingae intervertebral diskitis in an adult. Clin Infect Dis 1992; 15: 530–532.

de Groot R, Glover D, Clausen C, Smith AL, Wilson CB . Bone and joint infections caused by Kingella kingae: six cases and review of the literature. Rev Infect Dis 1988; 10: 998–1004.

Chew FS, Kline MJ . Diagnostic yield of CT-guided percutaneous aspiration procedures in suspected spontaneous infectious diskitis. Radiology 2001; 218: 211–214.

Koneman EW, Allen DS, Janda MW, Winn WC, Schreckenberger PC et al. The aerobic, Gram-positive bacilli. In: Koneman EW et al (eds), Diagnostic Microbiology, 5th edn. Lippincott: Philadelphia 1997, pp 651–708.

Kikuchi S, Muro K, Yoh K, Iwabuchi S, Tomida C, Yamaguchi N, Kobayashi M, Nagase S, Aoyagi K, Koyama A . Two cases of psoas abscess with discitis by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a complication of femoral-vein catheterization for haemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1999; 14: 1279–1281.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Atalay, B., Ergin, F., Teksam, M. et al. Spontaneous corynebacterium discitis in a patient with chronic renal failure. Spinal Cord 42, 378–381 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101532

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101532